Abstract

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome, Helicase, ATP hydrolysis, DNA unwinding, Inhibitor

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) by means of SARS coronavirus (SARS‐CoV) began in Guangdong of southern China in 2002, and led to almost 800 victims according to World Health Organization. During the outbreak of SARS, the patients were treated with conventional antiviral agents because of insufficient knowledge about SARS. Although SARS finally disappeared within a year, as of yet, effective medicine or vaccine has not been available. Therefore, development of successful anti‐SARS agents is necessary for possible outbreak in future.

In general, human CoVs, such as HCoV‐OC43 or HCoV‐229E, are enveloped viruses that propagate in the cytoplasm of the host and not regarded as fatal. However, SARS was caused by a new CoV that was not reported previously. Investigation of SARS‐CoV genome revealed that SARS‐CoV is a single‐stranded (ss) RNA (+)‐strand virus with a genome of about 29.7 kb.1, 2 On infection of host cells, a 21.2‐kb replicase gene, which is located at 5′‐end region of SARS‐CoV, is translated into two polyproteins, namely pp1ab and pp1a.3, 4 The synthesized polyproteins produce a few of nonstructural proteins (nsPs) after processing by proteinases.3, 5 Of the generated nsPs, RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase (nsP12) and the NTPase/helicase (nsP13) are indispensable in viral replication.5, 6 Therefore, nsP12 and nsP13 may be good targets for the finding of anti‐SARS agents.

Helicase is a kind of molecular motor proteins that perform double‐stranded (ds) nucleic acid unwinding using the energy released from NTP hydrolysis.7, 8 Because of the important role of helicase in SARS‐CoV replication, many attempts to develop anti‐SARS agents have been published against helicase.9, 10, 11, 12 We have also made an effort to develop the inhibitors against SARS‐CoV helicase, which includes ssRNA aptamers, aryl diketoacids, and dihydroxychromone derivatives.13, 14, 15 In addition, natural compounds, such as myricetin and scutellarein, were found to have inhibitory effect on the function of helicase.16 To screen the compounds against helicase, we have conducted Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis assay and dsDNA unwinding assay.

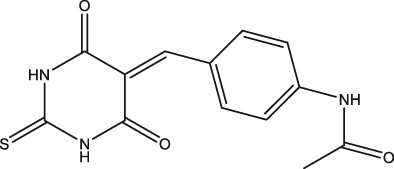

In the present study, we have identified a new chemical compound from purchased in‐house library as a result of our ongoing efforts to find SARS‐CoV helicase inhibitors. The compound was named as DTPMPA with a novel structure, N‐(4‐((4,6‐dioxo‐2‐thioxotetrahydropyrimidin‐5(2H)‐ylidene)methyl)phenyl)acetamide (Figure 1), which inhibits ATP hydrolysis as well as dsDNA unwinding activities of SARS‐CoV helicase.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of N‐(4‐((4,6‐dioxo‐2‐thioxotetrahydropyrimidin‐5(2H)‐ylidene)methyl)phenyl)acetamide.

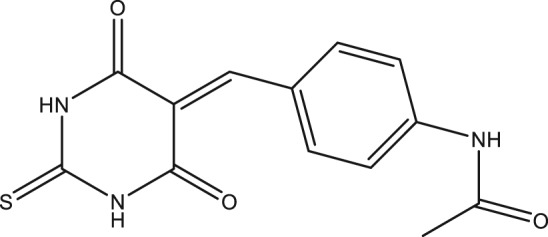

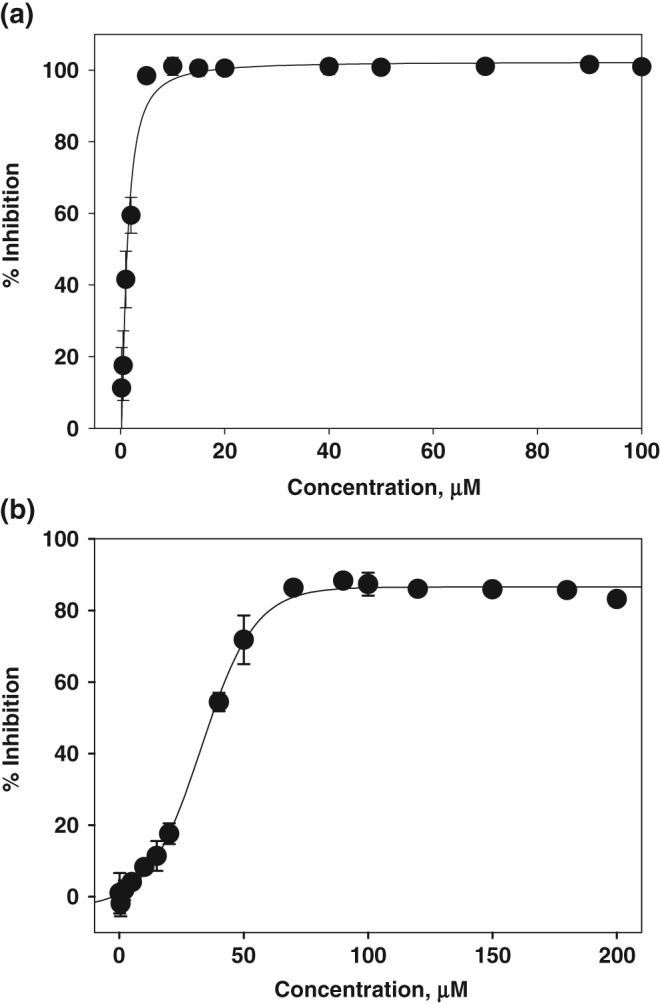

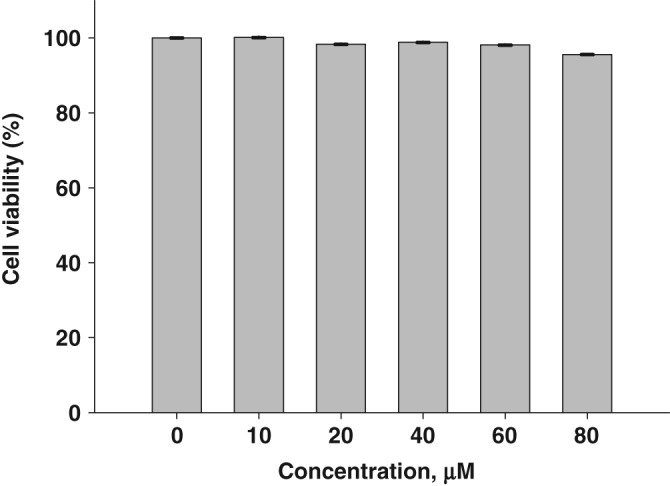

To determine whether DTPMPA inhibits the ATP hydrolysis activity, the color developed by molybdate complex formation was measured at 620 nm and the released Pi was calculated. Figure 2(a) shows the inhibition percentage of ATP hydrolysis by DTPMPA. To determine the IC50 value of DTPMPA, ATP hydrolysis assays were repeated in the presence of various concentrations of DTPMPA. As a result of the analysis, we were able to obtain the IC50 value of 1.19 ± 0.16 μM. In addition to ATP hydrolysis, fluorometric assays were also performed to determine whether DTPMPA inhibits dsDNA unwinding. In case two DNA strands were base‐paired, no fluorescence signal was monitored due to quenching by black hole quencher (BHQ). However, strong fluorescence signal was detectable when dsDNA was unwound by helicase. Based on this experimental setup, we measured inhibition of dsDNA unwinding by helicase in the presence of various concentrations of DTPMPA, as shown in Figure 2(b). IC50 value of DTPMPA was obtained from this analysis and determined to be 32.9 ± 1.0 μM. Furthermore, we have exposed normal WI‐38 cells (fetal lung tissue of human) to various concentrations of DTPMPA and performed 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay to determine whether DTPMPA has potential cytotoxicity. As shown in Figure 3, DTPMPA possesses no cytotoxicity to WI‐38 cells in the presence of concentrations used. This suggests that DTPMPA is a safe chemical compound at pharmacologically effective concentration.

Figure 2.

Percentage inhibition of SARS‐CoV helicase by N‐(4‐((4,6‐dioxo‐2‐thioxotetrahydropyrimidin‐5(2H)‐ylidene)methyl)phenyl)acetamide: (a) ATP hydrolysis activity and (b) dsDNA unwinding activity.

Figure 3.

Measurement of cell viability in the presence of N‐(4‐((4,6‐dioxo‐2‐thioxotetrahydropyrimidin‐5(2H)‐ylidene)methyl)phenyl)acetamide.

In summary, we identified a novel chemical compound, DTPMPA, as an inhibitor against SARS‐CoV helicase. DTPMPA was found to have inhibitory effects on ATP hydrolysis as well as dsDNA unwinding. Moreover, DTPMPA did not show any cytotoxic effect when we treated it to normal cells. Thus far, the reported synthesized and naturally occurring compounds targeting SARS‐CoV helicase are known to suppress selectively either ATP hydrolysis or dsDNA unwinding.14, 15, 16 Previous studies have demonstrated that the synthesized dihydroxychromone derivatives, which is a bioisostere of aryl diketoacid, inhibit only dsDNA unwinding.15 However, myricetin and scutellarein, which are naturally occurring flavonoids similar to dihydroxychromone derivatives, inhibit only ATP hydrolysis.16 The reason for this discrepancy is not known at present, but this may be due to substituents attached to diketoacid core. In fact, depending on the kind of group attached, various degrees of ATP hydrolysis or dsDNA unwinding inhibition were observed in case of dihydroxychromone derivatives.15 Although precise mechanism of how DTPMPA inhibits both ATP hydrolysis and dsDNA unwinding is unclear at present due to insufficient structural information, DTPMPA is thought to hold a great potential for use in treating SARS, specifically targeting helicase, after elaborate investigation in future.

Experimental

Protein

Expression vector encoding SARS‐CoV helicase was transformed into E. coli RosettaTM (Novagen), expressed, and purified as described previously.13, 14 The protein concentration was determined by measurement of absorbance at 280 nm and its extinction coefficient.

ATP Hydrolysis Assay

ATP hydrolysis by helicase was assayed by measuring the amount of released phosphate (Pi) from ATP using a colorimetric assay as described previously.14, 15 Colorimetric measurements of complex formation with malachite green and ammonium molybdate (AM/MG) were carried out in the presence of various concentrations of the chemical compound. After 0.5 μL of various concentrations of DTPMPA was placed on each well of the 96‐well plate, a 25 μL solution of 400 nM helicase in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 6.6) was added to each well. After 5 min incubation at room temperature, ATP hydrolysis reaction was started by addition of another 25 μL solution containing 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM ATP, and 4 nM circular M13 ssDNA in 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 6.6) to each well. The mixture was further reacted for 10 min at 37°C and the reaction was stopped by adding 200 μL of AM/MG reagent (0.034% MG, 1.05% AM, and 0.04% Tween 20 in 1 M HCl). The developed color was monitored by measuring at 620 nm and the released Pi was calculated using a standard curve. All experiments were repeated thrice and averaged.

DNA Unwinding Assay

BHQ‐labeled 45‐base‐DNA oligomer and Fluorescein‐labeled 25‐base‐DNA oligomer were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). The base sequences of BHQ‐labeled and Fluorescein‐labeled DNAs were as follows: 5′‐20T25 BHQ (5′‐T20GAGCGGATTACTATACTACATTAGA(BHQ)‐3′) and 3′‐0T25Flu (5′‐(Fluorescein)TCTAATGTAGTATAGTAATCCGCTC‐3′). The dsDNA substrate of helicase was prepared by annealing 5′‐20T25BHQ and 3′‐0T25Flu. The 5′‐20 T25 BHQ was synthesized to have a 20‐base dT tail at the 5′‐terminus to load the SARS‐CoV helicase. After 1 μL of various concentrations of DTPMPA was placed on each well of the 96‐well plate, a 80 μL solution of 150 nM helicase in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) was added to each well. After 5 min incubation at room temperature, dsDNA unwinding reaction was started by addition of 20 μL 5× reaction solution (5 mM MgCl2, 45 mM ATP, 25 mM DTT, and 100 nM dsDNA substrate in 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]). The mixture was further reacted for 2 min at 37°C and the reaction was stopped by addition of 100 μL termination solution (0.1 M EDTA and 0.4 μM trap DNA [unmodified 25‐base 3′‐0 T25 DNA oligomer] in 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]). The sample was excited at 485 nm and the fluorescence was measured at 535 nm.

Cell Viability Assay

WI‐38 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) media containing 10% heat‐inactivated fetal calf serum, 1% nonessential amino acid, streptomycin (100 µg/mL), and penicillin (100 units/mL) at 37°C in 5% CO2. The WI‐38 cells were placed onto a 96‐well plate at a density of 6 × 104 cells/mL. After 24 h, DTPMPA was added to a final concentration of 10, 20, 40, 60, and 80 μM and cells were further incubated for 48 h. Then, 50 μL of MTT stock solution (2 mg/mL) was suplemented to each well to make a total reaction volume of 250 μL. The supernatant was removed after 2 h incubation and the formazan crystal in each well was dissolved in 150 μL dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance at 540 nm was read using a scanning multiwell spectrophotometer.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF‐2013R1A1A2A10061193).

References

- 1. Marra M. A., Jones S. J., Astell C. R., Holt R. A., Brooks‐Wilson A., Butterfield Y. S., Khattra J., Asano J. K., Barber S. A., Chan S. Y., Cloutier A., Coughlin S. M., Freeman D., Girn N., Griffith O. L., Leach S. R., Mayo M., McDonald H., Montgomery S. B., Pandoh P. K., Petrescu A. S., Robertson A. G., Schein J. E., Siddiqui A., Smailus D. E., Stott J. M., Yang G. S., Plummer F., Andonov A., Artsob H., Bastien N., Bernard K., Booth T. F., Bowness D., Czub M., Drebot M., Fernando L., Flick R., Garbutt M., Gray M., Grolla A., Jones S., Feldmann H., Meyers A., Kabani A., Li Y., Normand S., Stroher U., Tipples G. A., Tyler S., Vogrig R., Ward D., Watson B., Brunham R. C., Krajden M., Petric M., Skowronski D. M., Upton C., Roper R. L., Science 2003, 300, 1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rota P. A., Oberste M. S., Monroe S. S., Nix W. A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J. P., Penaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M. H., Tong S., Tamin A., Lowe L., Frace M., DeRisi J. L., Chen Q., Wang D., Erdman D. D., Peret T. C., Burns C., Ksiazek T. G., Rollin P. E., Sanchez A., Liffick S., Holloway B., Limor J., McCaustland K., Olsen‐Rasmussen M., Fouchier R., Gunther S., Osterhaus A. D., Drosten C., Pallansch M. A., Anderson L. J., Bellini W. J., Science 2003, 300, 1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lai M. M., Cavanagh D., Adv. Virus Res. 1997, 48, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ziebuhr J., Snijder E. J., Gorbalenya A. E., J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ivanov K. A., Thiel V., Dobbe J. C., van der Meer Y., Snijder E. J., Ziebuhr J., J. Virol. 2004, 78, 5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tanner J. A., Watt R. M., Chai Y. B., Lu L. Y., Lin M. C., Peiris J. S., Poon L. L., Kung H. F., Huang J. D., J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 39578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel S. S., Donmez I., J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 18265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel S. S., Picha K. M., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000, 69, 651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanner J. A., Zheng B. J., Zhou J., Watt R. M., Jiang J. Q., Wong K. L., Lin Y. P., Lu L. Y., He M. L., Kung H. F., Kesel A. J., Huang J. D., Chem. Biol. 2005, 12, 303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang N., Tanner J. A., Wang Z., Huang J. D., Zheng B. J., Zhu N., Sun H., Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2007, 42, 4413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adedeji A. O., Singh K., Calcaterra N. E., DeDiego M. L., Enjuanes L., Weiss S., Sarafianos S. G., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adedeji A. O., Singh K., Kassim A., Coleman C. M., Elliott R., Weiss S. R., Frieman M. B., Sarafianos S. G., Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jang K. J., Lee N. R., Yeo W. S., Jeong Y. J., Kim D. E., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 366, 738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee C., Lee J. M., Lee N. R., Jin B. S., Jang K. J., Kim D. E., Jeong Y. J., Chong Y., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee C., Lee J. M., Lee N. R., Kim D. E., Jeong Y. J., Chong Y., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yu M. S., Lee J., Lee J. M., Kim Y., Chin Y. W., Jee J. G., Keum Y. S., Jeong Y., J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]