Abstract

Patient: Male, 62-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) adherent to the spleen and the tail of the pancreas

Symptoms: Melena

Medication:—

Clinical Procedure: En bloc sphenoid gastrectomy • splenectomy • caudal pancreatectomy

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

are disease

Background:

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal gastrointestinal tumors (GIT). Usually, they appear in patients ages 55–65 years, with no apparent difference between males and females. Their annual incidence is about 11–14 per 106. They generally do not present with any prominent symptoms, appearing with the atypical symptoms of abdominal pain, weight loss, early satiety, and occasionally bleeding. Adequate surgical treatment involves sphenoid resection of the tumor within clear margins. If adjacent organs are involved, en bloc resection is the procedure of choice.

Case Report:

A 62-year-old male patient presented to the Emergency Department complaining of melena for 1 week. He underwent gastroscopy, colonoscopy and abdominal computed tomography scan, which revealed a large, exophytic, lobular mass (12.6×9.7×12 cm) of the greater curvature of the stomach. The patient underwent en bloc sphenoid gastrectomy, splenectomy, and caudal pancreatectomy. The histopathologic examination revealed findings compatible with a gastrointestinal stromal tumor located at the stomach, with low-grade malignancy (G1) and T4N0 according to TNM classification. He was discharged from the hospital on the 7th postoperative day.

Conclusions:

GISTs are uncommon tumors of the gastrointestinal system that usually do not invade neighboring organs or develop distant metastases; therefore, local resection is usually the treatment of choice. However, in cases of large GISTs that are adherent to neighboring organs, en bloc resection and resection of adjacent organs may be inevitable.

MeSH Keywords: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors, Pancreas, Spleen, Stomach Neoplasms

Background

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are a type of mesenchymal tumor that appear in the gastrointestinal tract, originating from the Cajal interstitial cells [1]. In the USA, the incidence of GISTs is around 11–14 per 106, while in Europe recent estimates put the incidence at around the same values (1: 105). The mean age at diagnosis is 55–60 years, with no apparent difference between males and females [2,3]. It is estimated that more than half of GISTs (50–60%) are in the stomach, 30% are in the jejunum or ileum, 5% are in the duodenum, 5% are in the rectum, and less than 1% are in the esophagus [4]. Approximately 1 in 3 GISTs are asymptomatic and are detected incidentally during screening imaging studies or abdominal surgical procedures. Symptomatic GISTs appear with gastrointestinal bleeding (varying from insidious chronic bleeding to life-threatening acute bleeding), usually along with gastric discomfort mimicking the symptoms of an ulcer. Few GISTs manifest as other abdominal emergencies, such as intestinal obstruction, or with rupture resulting in hemoperitoneum [4]. The preferred treatment for GISTs is total surgical resection of the tumor. In cases of large tumors and invasion of neighboring organs, en bloc resection of the tumor together with the neighboring organs might be needed [5].

We present the case of a 62-year-old man who was diagnosed with GIST. Due to its adhesion to the pancreas and the spleen, he underwent en bloc sphenoid gastrectomy, splenectomy, and caudal pancreatectomy.

Case report

A 62-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department complaining of melena for 1 week accompanied by feeling of early satiety and weight loss of approximately 10 kg in the span of 2 months, with no related pain, abdominal discomfort, or palpable abdominal masses. He was initially admitted to the Gastroenterology Department, where he underwent laboratory and imaging studies. All the laboratory results, including the tumor markers, were within normal values. Imaging studies included gastroscopy, colonoscopy, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan. The colonoscopy did not reveal any abnormal lesions, while the gastroscopy showed a submucosal mass with mucosal ulceration in the greater curvature of the stomach (Figure 1), and the CT scan (Figure 2) revealed a large lobular mass (12.6×9.7×12 cm) originating from the greater curvature of the stomach, with adhesion to the neighboring organs (spleen and pancreas). He was transferred to our Surgical Department, where he underwent exploratory laparotomy, which revealed an exophytic mass of the stomach, in agreement with the findings of the CT scan (Figures 3, 4). Therefore, en bloc sphenoid gastrectomy, splenectomy, and caudal pancreatectomy were performed (Figure 5). A drainage tube was placed in the left subdiaphragmatic space at the site of the splenectomy. The patient recovered safely in the operating room and was transferred back to the floor.

Figure 1.

Gastroscopy image of the submucosal mass and ulceration on the greater curvature of the stomach.

Figure 2.

CT scan image showing a large lobular mass originating from the greater curvature of the stomach.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative image showing adhesion of the tumor to the spleen.

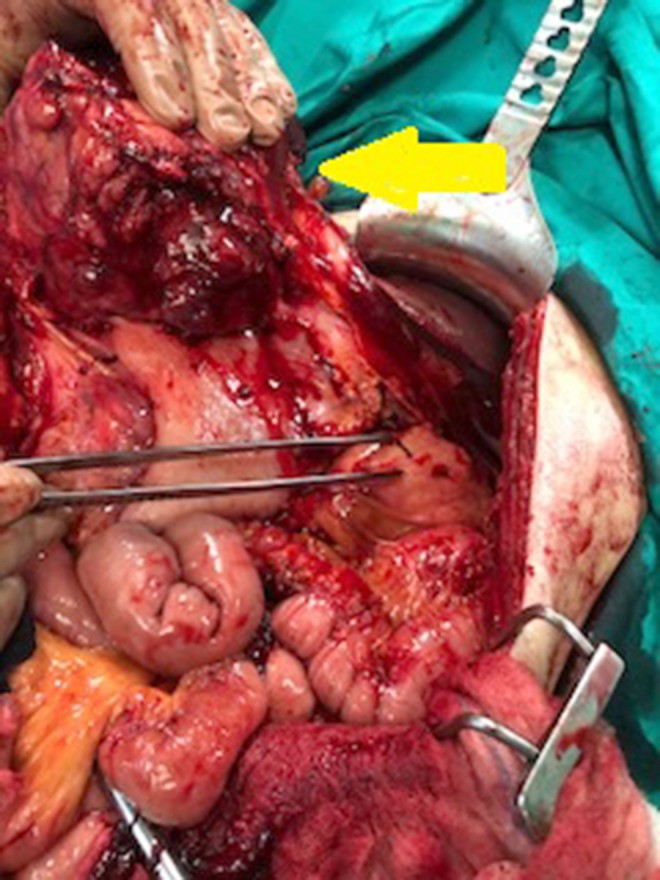

Figure 4.

Intraoperative image showing the tumor (yellow arrow) and its adhesion to the pancreas (forceps).

Figure 5.

The specimen after being excised.

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. The naso-gastric tube was removed on the 4th postoperative day and the drainage tube was removed 2 days later. Oral intake of liquids began on the 4th postoperative day and he was discharged on the 7th postoperative day.

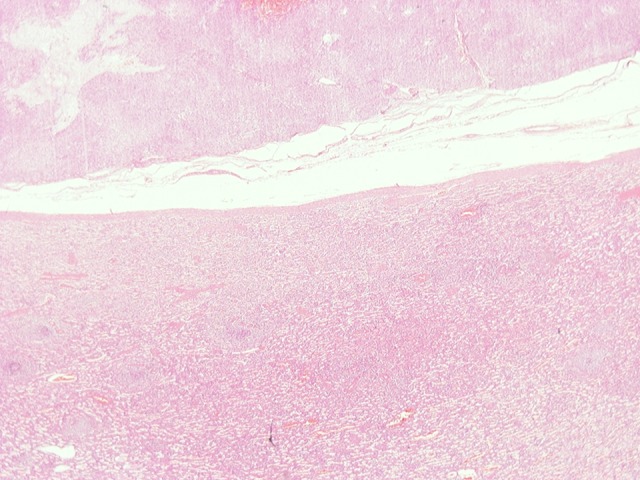

The histopathologic examination of the specimen revealed histologic and immunochemical findings compatible with low-grade (G1) gastric GIST, staged pT4pN0 according to the TNM staging system. Specifically, the immunochemical control showed strong positivity for C-KIT, DOG1, and caldesmon neo-plastic cells, and weaker positivity for SMA and negative for desmin, CD34 antigen, keratin 8/18, and S100 protein. The mitotic index KI67/MIB1 was positive up to 2% in the majority of the neoplastic cells, but there were a few sites where it reached 15%. The margins of the stomach were free of neoplastic disease, and the spleen and the pancreas did not show evidence of invasion from the tumor. Gross pathological examination of the specimen revealed a 21-cm nodular mass, tan-white on sectioning, confined to the gastric submucosa, without invasion of the gastric mucosa. Histological examination of this lesion showed a tumor composed of spindle or polygonal cells, with eosinophilic cytoplasm, poorly-defined cell membranes, and round or elongated nuclei forming palisades, with occasional perinuclear vacuolization. The neoplastic cells were arranged in intersecting bundles and occasionally in whorls. A few necrotic spots were observed. The mitotic rate was low (1 mitosis per 50 high-power fields), and there was no evidence of tumor cells in surgical margins (R0 excision). Neither the pancreatic nor the splenic parenchyma were invaded by the neoplasm. Immunohistochemically, neoplastic cells were diffuse and strongly stained for C-KIT (CD117), DOG1, and caldesmon, weakly stained for smooth muscle actin (SMA), and not stained for desmin and CD34. The Ki67-labeling index ranged from 2% to 15%, with a median of 3.3% (Figures 6–8).

Figure 6.

(HE ×40) Pancreatic parenchyma without neoplastic involvement.

Figure 7.

(HE ×20) Neoplastic tissue without gastric-mucosal involvement.

Figure 8.

(HE ×20) Splenic parenchyma is not involved by neo-plastic tissue.

After an oncologic consultation, the patient was started on 400 mg of imatinib per day and he remains disease-free 6 months postoperatively.

Discussion

GISTs are mesenchymal tumors originating from the intestinal cells of Cajal and can be found in every part of the gastrointestinal tract [1]. Usually, they are localized tumors <5 cm in diameter, with extremely low occurrence of lymph node metastases [6–8]. The most common sites of distant metastases for gastric GISTs are the peritoneal cavity and liver. Few cases of distant metastases to bones have been observed, predominantly on the axial skeleton, usually the spine. Metastases to the surrounding cutaneous and peripheral soft tissues are very rare; in contrast to other malignant sarcomas, lung metastases almost never occur [4]. Consequently, the standard treatment for gastric GISTs is wedge or segmental resection of the tumor. The main goal is to avoid tumor rupture and to achieve clear margins of excision (R0) with the fewest possible post-surgical comorbidities [2,9].

In a retrospective study by Lanping Zhu et al., endoscopic re-section of 250 GISTs less than 2 cm in diameter was reported. Apart from 67 cases of intraoperative bleeding managed endoscopically with surgical clips and nylon bands, no other major complications were reported during their 8.5-year postoperative surveillance period. During this period, 80.2% of patients reported improvement of symptoms and no recurrence or metastasis was found [10]. The same tumor size of 2 cm is reported as a criterion for endoscopic resection in a systematic review by Qiang Zhang et al., who gathered data from 11 different studies investigating endoscopic resection of GISTs, reporting a recurrence rate up to 5.8% after a follow-up period of 32 months [11]. In contrast, a study by Changji Yu in 2017 proposed endoscopic full-thickness resection for the treatment of GISTs up to 5 cm in diameter [12]. Regarding laparoscopic resection of GISTs, a study published in 2017 suggested that the upper limit for laparoscopic excision of GISTs is 5 cm in diameter, with some researchers reporting laparoscopic excisions in tumors 5–10 cm in diameter [13,14].

However, in cases in which either the tumor size or its location renders a R0 surgical excision not feasible or when it there is increased risk of post-surgical morbidity, neo-adjuvant treatment with imatinib, attempting to shrink the tumor and facilitate its excision, has been recommended [8,15]. Nonetheless, in our case, due to acute gastrointestinal bleeding presenting with melena, emergency surgery was elected over neo-adjuvant therapy in accordance with the recent literature [16]. In cases in which there is adherence or infiltration of the surrounding organs by the tumor, en bloc excision of the tumor with all the involved surrounding structures is recommended [9]. Therefore, in our case, following the recommended surgical guidelines, we performed en bloc sphenoid gastrectomy, splenectomy, and caudal pancreatectomy.

Generally, infiltrating GISTs are rarely encountered. According to a report by Magdy et al., among 49 gastric GISTs, only 2 required partial gastrectomy, splenectomy, and distal pancreatectomy, while Weili Yang et al. reported 2 more cases that needed multivisceral en bloc resection, one with partial colectomy and another with distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy [17,18]. Another case report, published in 2016, reported resection of a GIST en bloc with the spleen and a full-thickness cuff of the diaphragm [19]. Finally, 2 more case reports, one by Kondo et al. and one by Namikawa et al., reported cases similar to ours, with gastric GISTs that required en bloc splenectomy and caudal pancreatectomy. However, in these 2 cases, the operations were performed after long-term therapy with imatinib [20,21].

Conclusions

GISTs are uncommon tumors of the gastrointestinal system that are usually asymptomatic and are often found incidentally. They are usually small and thus can be removed endoscopically or laparoscopically, utilizing the advantages of minimally invasive surgery. However, in cases of large GISTs that are adhering to neighboring organs, en bloc resection of adjacent organs such as the spleen or pancreas may be required.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Starczewska Amelio JM, Cid Ruzafa J, Desai K, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) in the United Kingdom at different therapeutic lines: An epidemiologic model. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:364. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rammohan A, Sathyanesan J, Rajendran K, et al. A gist of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5(6):102–12. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v5.i6.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casali P G, Abecassis N, Bauer S, et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee and EURACAN; Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;28(4):68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42(2):399–415. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poveda A, del Muro XG, López-Guerrero JA, et al. GEIS 2013 guidelines for gastrointestinal sarcomas (GIST) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74(5):883–98. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2547-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishida T, Blay JY, Hirota S, et al. The standard diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on guidelines. Gastric Cancer. 2015;19(1):3–14. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0526-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akahoshi K, Oya M, Koga T, Shiratsuchi Y. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(26):2806–17. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez-Hidalgo JM, Duran-Martinez M, Molero-Payan R, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A multidisciplinary challenge. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(18):1925–41. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i18.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koo DH, Ryu MH, Kim KM, et al. Asian Consensus Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48(4):1155–66. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu L, Khan S, Hui Y, et al. Treatment recommendations for small gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Positive endoscopic resection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(3):297–302. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1578405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q, Gao LQ, Han ZL, et al. Effectiveness and safety of endoscopic re-section for gastric GISTs: A systematic review. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2018;27(3):127–37. doi: 10.1080/13645706.2017.1347097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu C, Liao G, Fan C, et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic resection of gastric GISTs. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(11):4799–804. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5557-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CM, Park S. Laparoscopic techniques and strategies for gastrointestinal GISTs. J Vis Surg. 2017;3:62. doi: 10.21037/jovs.2017.03.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi J-L, Xu M, Zhang M-R, Li Y, Zhou Z-G. Laparoscopic versus open resection for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): A size-location-matched case-control study. World J Surg. 2017;41(9):2345–52. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwatsuki M, Harada K, Iwagami S, et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;3(1):43–49. doi: 10.1002/ags3.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Q, Kong F, Zhou J, et al. Management of hemorrhage in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A review. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:735–43. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S159689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorour MA, Kassem MI, Ghazal Ael-H, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST)-related emergencies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(4):269–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang W, Yu J, Gao Y, et al. Preoperative imatinib facilitates complete resection of locally advanced primary GIST by a less invasive procedure. Med Oncol. 2014;31(9):133. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Annapoorni S. Segmental gastric resection with splenectomy for a malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the stomach. Hellenic J Surg. 2016;88:119. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo J, Chijimatsu H, Kijima T, et al. [A case of gastric GIST with pathological complete response achieved by long-term chemotherapy with imatinib mesylate] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2018;45(3):515–17. [in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Namikawa T, Munekage E, Munekage M, et al. Synchronous large gastrointestinal stromal tumor and adenocarcinoma in the stomach treated with imatinib mesylate followed by total gastrectomy. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(4):1855–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]