SUMMARY

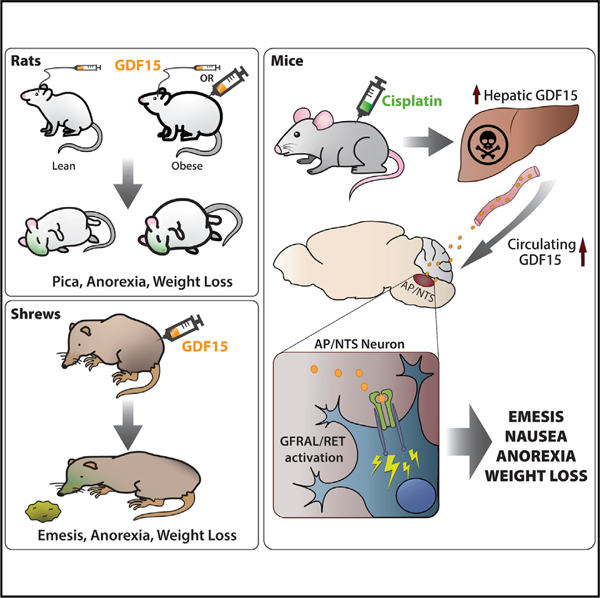

Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) is a cytokine that reduces food intake through activation of hindbrain GFRAL-RET receptors and has become a keen target of interest for anti-obesity therapies. Elevated endogenous GDF15 is associated with energy balance disturbances, cancer progression, chemotherapy-induced anorexia, and morning sickness. We hypothesized that GDF15 causes emesis and that its anorectic effects are related to this function. Here, we examined feeding and emesis and/or emetic-like behaviors in three different mammalian laboratory species to help elucidate the role of GDF15 in these behaviors. Data show that GDF15 causes emesis in Suncus murinus (musk shrews) and induces behaviors indicative of nausea/malaise (e.g., anorexia and pica) in non-emetic species, including mice and lean or obese rats. We also present data in mice suggesting that GDF15 contributes to chemotherapy-induced malaise. Together, these results indicate that GDF15 triggers anorexia through the induction of nausea and/or by engaging emetic neurocircuitry.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

This work assesses whether or not GDF15 produces emesis and/or emetic-like behaviors in the vomiting shrew (Suncus murinus) and non-vomiting rat. The results suggest that exogenous delivery of GDF15 produces either emesis or emetic-like behavior (i.e., pica) prior to the induction of anorexia in shrews and rats, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15), also known as macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1), is a stress response cytokine expressed in a variety of tissue and secreted into circulation in response to many stimuli as part of a wide variety of disease processes, including cancer and obesity (Bauskin et al., 2006; Mullican and Rangwala, 2018; Staff et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2018). GDF15 signaling has gained significant attention with the nearly simultaneous recent reporting of the identification and characterization of the GFRAL-RET (GDNF family receptor α-like) receptor complex as the cellular target for GDF15-mediated signaling (Emmerson et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2017; Mullican et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). Since this cluster of findings, numerous reports and reviews have demonstrated promise for GDF15-GFRAL signaling in obesity treatment (Frikke-Schmidt et al., 2019; Patel et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2018). Recently published data (Hsu et al., 2017) have suggested that GFRAL knockout (KO) mice were insensitive to long-term anorexia and weight loss produced by the highly emetogenic and widely prescribed chemotherapy agent cisplatin (Herrstedt, 2018). In this context, the reported restrictive central expression of GFRAL to the area postrema (AP) and contiguous nucleus of the tractus solitarius (NTS) (here, collectively referred to as AP/NTS) (Emmerson et al., 2017; Mullican et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017), brainstem nuclei highly critical to both energy balance and emesis and/or emetic-like behaviors (e.g., nausea, malaise, pica, and geophagia), suggests that GDF15-GFRAL signaling could be an important factor, not only in long-term energy balance, but also emesis and nausea. The notion that GDF15 likely produces aversive responses has gained support (O’Rahilly, 2017; Patel et al., 2019); however, whether GDF15 produces emesis and/or emetic-like behaviors has not been directly tested.

Previous data published in tumor-bearing rats suggest that the AP/NTS is a critical mediator of cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome (CACS) in a hepatoma model, a condition paralleled by significant increases in plasma GDF15 and tumor-induced anorexia (Borner et al., 2016). In fact, lesioning of the AP in these animals was sufficient to completely block the anorexia and body weight loss induced in this tumor-bearing model. Parallel data (Tsai et al., 2014) showed that similar lesions of the AP/NTS were able to block GDF15-induced anorexia and body weight loss in mice. This demonstrates that the effects of AP lesioning are due in large part to the ablation of the CNS region primarily responsible for mediating GDF15-induced anorectic effects.

The literature clearly supports the notions that (1) chemotherapy-induced nausea and anorexia correlate with GDF15 signaling, (2) an AP/NTS site of action exists for GDF15 (i.e., through binding in the only reported central location of the GFRAL-RET receptor complex), and (3) cisplatin increases circulating GDF15 in mice and humans (Altena et al., 2015; Hsu et al., 2017). These data are of clinical relevance given that nausea and anorexia induced by chemotherapy remain important clinical problems, even when vomiting is well controlled (Basch et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2007; Van Laar et al., 2015). Indeed, while serotonin (5-HT) is classically known to play a key role in emesis (Endo et al., 2000), with 5-HT receptor 3 (5-HT3R) antagonists (e.g., ondansetron; Ond) being among the most widely used antiemetics (Aapro, 2005; Herrstedt, 2018), many patients under-going emetogenic chemotherapy receiving 5-HT3R antagonists, alone or in combination with other antiemetics (e.g., aprepitant and olanzapine), still report feeling ill and have reduced appetite following treatment (Feyer and Jordan, 2011; Grunberg et al., 2004; Hesketh, 2008; Keeley, 2009; Sutherland et al., 2018). Given that both hindbrain terminal vagal afferent fibers and AP/ NTS neurons express 5-HT3Rs, which are collectively thought to contribute to the intake suppressive effects and nausea/ emesis of chemotherapy (Browning, 2015; Leon et al., 2019), testing whether antagonizing vagal or brainstem 5-HT3R signaling influences AP/NTS GDF15-GFRAL signaling could be of relevance to anorexia and nausea/emesis.

As many ongoing trials are underway examining the GDF15 system, an open question is whether or not, in addition to long-term changes in anorexia and body weight loss, exogenous GDF15 administration can produce behaviors indictive of nausea and/or emesis (specifically in species that can vomit). Emesis and nausea can be modeled in both emetic and non-emetic species. Rodents, including laboratory rats and mice, lack the vomiting response (Horn et al., 2013). In the rat, pica behavior (i.e., ingestion of non-nutritive food such as kaolin clay) is a validated proxy for nausea (Alhadeff et al., 2017; De Jonghe and Horn, 2008; Liu et al., 2005), while in both mice and rats, conditioned flavor avoidance (CFA) has been used as a conditioned behavioral assay to screen for potential noxious stimuli (Bodnar, 2018; Parker, 2014). In contrast, the house musk shrew (Suncus murinus) is an established preclinical model for chemotherapy-induced emesis, as this mammal vomits and shares an emetic profile similar to humans (De Jonghe and Horn, 2009; Horn et al., 2011; Matsuki et al., 1988; Rudd et al., 2018; Ueno et al., 1987).

Here, we present a complementary set of data in rodents and shrews interrogating the impact of GDF15 on both emetic behaviors and energy balance. In mice, we corroborate the initial report of cisplatin-induced GDF15 increases in the circulation (Hsu et al., 2017) and extend these findings to show the predictive potential of GDF15 release in the immediate hours following cisplatin administration with the development of anorexia later (within days). We also show that cisplatin activates GFRAL+ neurons in the AP/NTS in mice. In both lean and high-fat/high-sucrose diet (HFSD)-induced obese rats, we report that central as well as systemic GDF15 administration potently induces kaolin intake and anorexia in a dose-dependent fashion; however, it is critical to note that the kaolin intake (pica behavior) precedes the anorectic effects of systemic or centrally delivered GDF15. Furthermore, we show that systemic Ond attenuates GDF15-induced anorexia, but not kaolin intake, while hindbrain administration of Ond has no effect on GDF15-induced anorexia or kaolin intake in lean rats. In the shrew, we show that GDF15 is a vomiting stimulus, with GDF15 inducing both acute vomiting, as well as long-term anorexia and body weight loss. Taken together, it is likely that nausea and emesis contribute to GDF15-mediated food intake suppressive effects, as well as off-target anorectic and body weight loss effects of many drugs associated with elevated GDF15 levels (e.g., chemotherapy).

RESULTS

Cisplatin Induces Higher Circulating GDF15 Levels and Activates GFRAL-Expressing Neurons in the AP/NTS of the Mouse

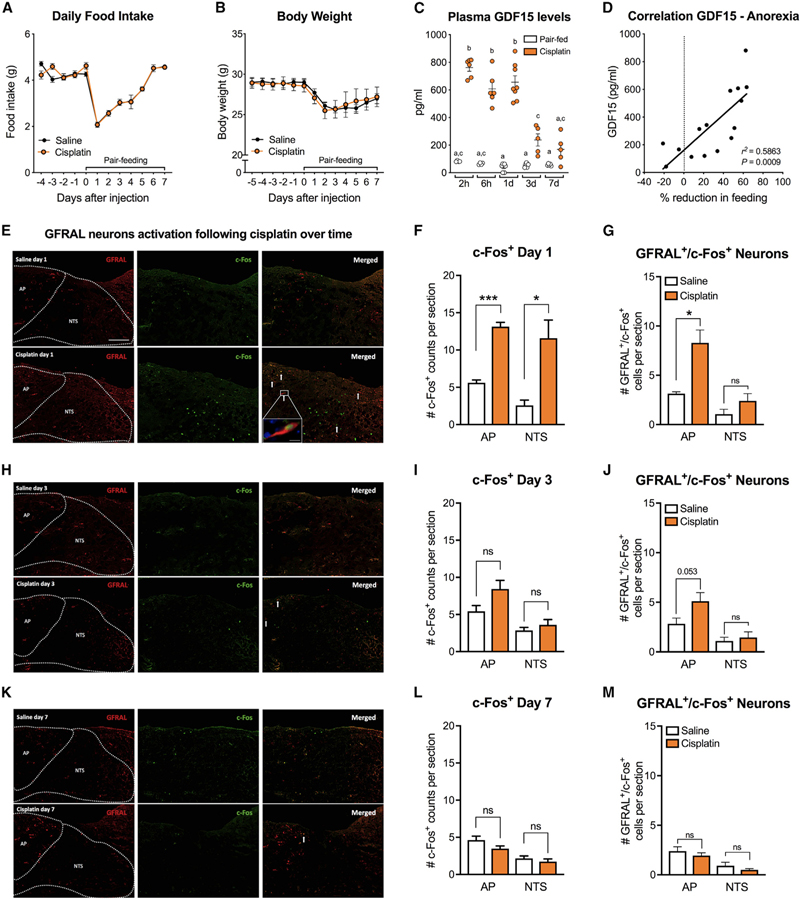

Here, we measured food intake, body weight, and circulating GDF15 levels for 7 days following cisplatin treatment (10 mg/ kg intraperitoneally [i.p.]) in mice. Cisplatin induced a chronic anorectic response accompanied by body weight loss (Figures 1A and 1B). No differences in body weight loss or recovery occurred between cisplatin-treated and pair-fed (PF) animals. GDF15 levels were significantly higher following cisplatin injection compared to PF controls at 2 h, 6 h, 1 day, and 3 days post-cisplatin-injection. No changes in GDF15 levels occurred in PF controls (Figure 1C). The magnitude of the anorectic response positively correlated with circulating GDF15 levels (Figure 1D). Furthermore, we show c-Fos expression in GFRAL+ neurons 24 h after cisplatin administration in the AP/NTS (Figures 1E and 1F). Specifically, 62% ± 8% of the activated neurons in the AP were GFRAL+ (Figure 1G). Conversely, 54% ± 8% of the AP GFRAL+ neurons were activated by cisplatin. In the NTS, only 19% ± 4% of the activated neurons expressed GFRAL (Figure 1G) and 36% ± 10% of the total NTS GFRAL+ population expressed c-Fos 24 h after cisplatin treatment. No significant differences in total c-Fos or GFRAL expression in the AP/NTS were noticed between cisplatin and PF animals 3 and 7 days after treatment (Figures 1G–1L).

Figure 1. Cisplatin Induces Higher Circulating GDF15 Levels and Activates GFRAL Positive Neurons in the AP/NTS of the Mouse.

(A) A single dose of cisplatin (10 mg/kg) induced a chronic anorectic response (n = 4–5 per group).

(B) Body weight between cisplatin-treated and pair-fed controls did not differ (n = 4–5 per group).

(C) Plasma GDF15 levels were higher at 2, 6, and 24 h after cisplatin injection and slowly returned to baseline 7 days after (n = 4–8 per group).

(D) The magnitude of anorexia across time positively correlated with circulating GDF15 levels (n = 15).

(E) Representative sections of the AP/NTS showing the distribution of GFRAL neurons and the colocalization with of the marker of neuronal activation c-Fos 24 h after cisplatin or saline injection.

(F) Quantification of cisplatin-induced c-Fos expression in the AP/NTS 24 h upon injection (n = 4–5 per group).

(G) Number of GFRAL-positive neurons in the AP/NTS that co-express c-Fos 24 h after cisplatin administration (n = 4–5 per group).

(H) Representative sections of the AP/NTS depicting GFRAL neurons and c-Fos 3 days after cisplatin or saline injection.

(I) Quantification of c-Fos expression in the AP/NTS 3 days after drug administration (n = 5 per group).

(J) Number of GFRAL-positive neurons in the AP/NTS that co-express c-Fos 3 days upon treatment (n = 5 per group).

(K) Representative sections of the AP/NTS showing GFRAL neurons and c-Fos 7 days after treatment.

(L) Quantification of c-Fos expression in the AP/NTS 7 days after drug administration (n = 5 per group).

(M) Number of GFRAL-positive neurons in the AP/NTS that co-express c-Fos 7 days after treatment (n = 5 per group).

All data but in (D) are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data in (C) analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. Means with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Quantification data in (F, G, I, J, L, and M) analyzed with the Student’s t-test; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.0001. Arrows represent c-Fos/ GFRAL neurons. Scale bar 100 µm. Inset in (E) is a high-power (60x) photomicrograph showing a GFRAL-positive neuron co-expressing c-Fos in the AP. Scale bar 10 mm.

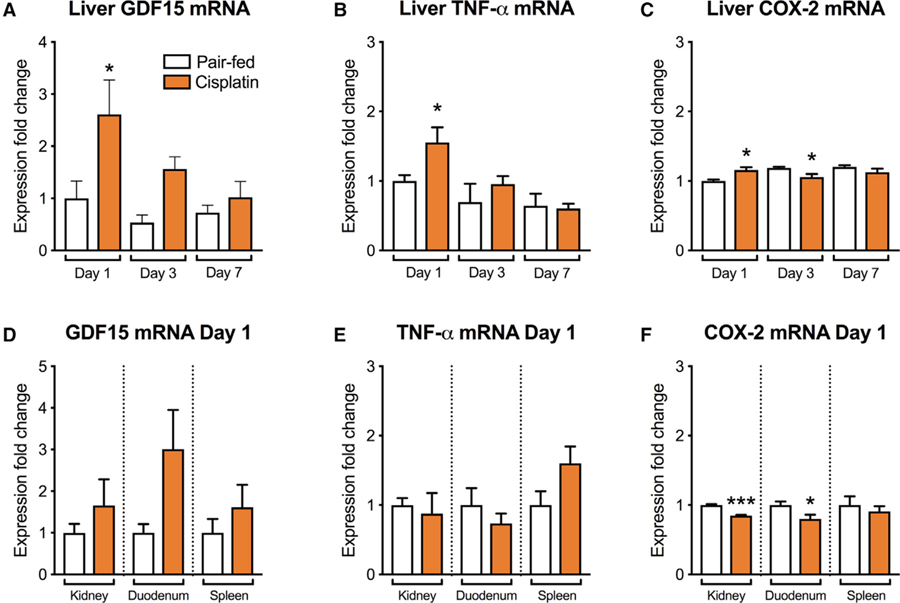

We analyzed GDF15, TNF-α, and COX-2 transcripts in the liver, kidney, duodenum, and spleen in order to potentially identify peripheral sources of cisplatin-induced elevations in circulating GDF15. We observed significantly higher GDF15, TNF-α, and COX-2 mRNA levels at 1 day after cisplatin in the liver but not in the other tissues analyzed compared to controls (Figures 2A–2F).

Figure 2. Hepatic, but Not Renal, Duodenal, nor Splenic GDF15 mRNA Expression Is Upregulated Following Cisplatin.

(A) Hepatic GDF15 mRNA was higher at day 1 after cisplatin injection compared to controls. No significant differences in GDF15 mRNA expression occurred at day 3 and day 7.

(B) Hepatic TNF-a mRNA was higher at day 1 after cisplatin injection compared to controls. No significant differences occurred at later timepoints.

(C) In cisplatin-treated animals, COX-2 mRNA expression in the liver was higher at 1 day, lower at 3 days, and unaltered at 7 days compared to the relative PF groups.

(D) GDF15 mRNA levels in the kidney, duodenum, and spleen were unaltered at day 1 upon cisplatin administration compared to controls.

(E) TNF-a mRNA expression levels in the kidney, duodenum, and spleen were not affected by cisplatin administration at day 1.

(F) COX-2 mRNA transcripts were lower in the kidney and duodenum at day 1, while no change occurred in the spleen compared to their relative controls.

All data expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 4–5 per group. Data in (A–C) expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test; *p < 0.05. Data in (D–F) analyzed with the Student’s t test; ***p < 0.0001.

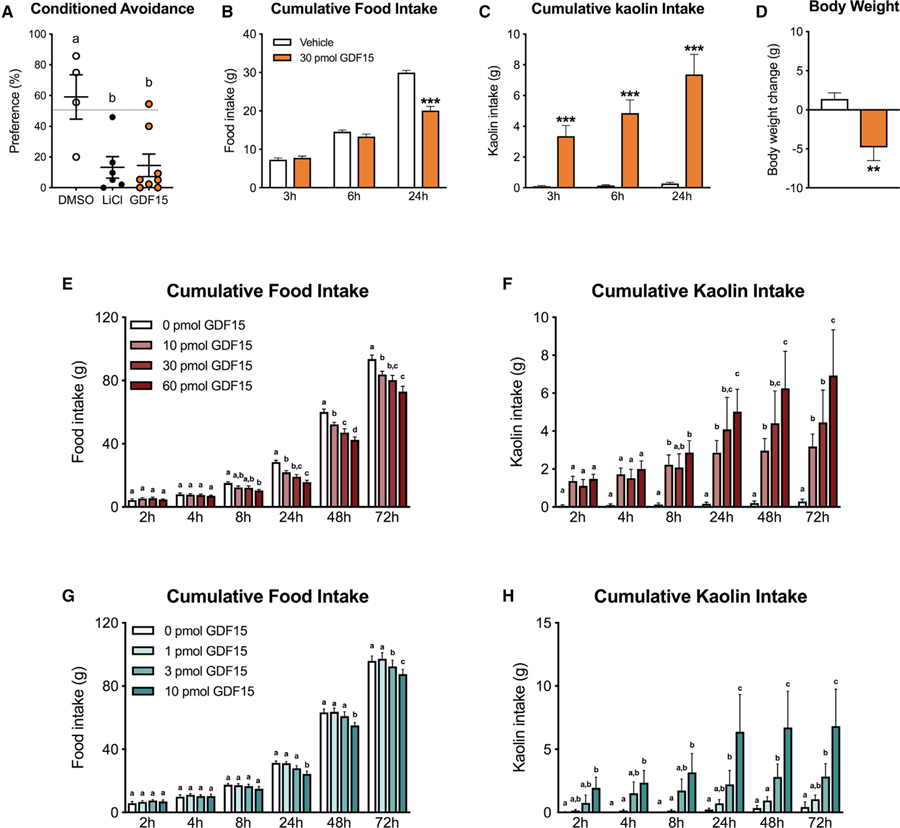

Central Delivery of GDF15 Induces CFA, Anorexia, and Pica in Rats

In initial experiments, we examined whether intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusion of GDF15 into the 4th ventricle induced CFA, anorexia, and/or pica in rats. We utilized the two-bottle preference test to evaluate the expression of a CFA in rats. As shown in Figure 3A, preference of the drug-paired flavor was significantly lower in the GDF15 group compared to controls (p < 0.05) and comparable to the positive control lithium chloride (LiCl). To further explore whether GDF15 causes pica when 2having anorectic effects, we measured kaolin and food intake in rats. GDF15 significantly suppressed food intake at 24 h post-administration compared to vehicle, but no significant reduction was noticed at earlier time points (Figure 3B). We observed marked kaolin consumption that preceded the onset of the anorectic response. Indeed, kaolin intake was significantly higher at all measured time points relative to controls (Figure 3C). GDF15 administration also induced body weight loss 24 h post-injection compared to vehicle treated animals (p < 0.01, Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Central GDF15 Delivery Induces CFA, Anorexia, Body Weight Loss, and Pica in Rats.

(A) The preference for the paired solution was significantly reduced after centrally delivered GDF15 (30 pmol i.c.v., n = 7) compared to negative controls (DMSO, 1 µL i.c.v., n = 4). LiCl (0.15 M, i.p., n = 6) was used as a positive control.

(B) GDF15 (30 pmol i.c.v., n = 22) significantly reduced 24 h food intake but did not cause anorexia at 3 or 6 h post-delivery compared to the control group.

(C) GDF15 administration triggered kaolin consumption at all time points and preceded the onset of the anorectic response.

(D) GDF15-induced anorexia was paralleled by significant body weight loss at 24 h post-injection compared to controls.

(E) GDF15 delivered at 10, 30, 60 pmol into the 4th ventricle induced anorexia compared to vehicle-treated animals (n= 10 per group).

(F) The same doses of GDF15 triggered kaolin consumption (i.e. pica) (n = 10 per group).

(G) In a separate cohort of rats, GDF15 was infused at 0, 1, 3, 10 pmol. While 1 pmol had no effect, all other tested doses induced anorexia (n = 10 per group).

(H) Similarly, all but the 1 pmol dose of GDF15 triggered pica (n = 10 per group). In general, pica preceded the onset of the hypophagic response across all the anorectic doses tested.

All data expressed as mean ± SEM. Data in (B and C) were analyzed with a repeated-measurements two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Data in (D) were analyzed with the Student’s t test. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data in (E–H) were analyzed with repeated-measure two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Means with different letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

A series of GDF15 dose-response experiments were conducted, where food and kaolin intake were measured over 72 h. In two cohorts of lean rats, GDF15 was delivered i.c.v. into the 4th ventricle at 0, 10, 30, and 60 (Figures 3E and 3F) or 0, 1, 3, and 10 pmol (Figures 3G and 3H), respectively. While 1 pmol had no effect on food or kaolin intake when compared to vehicle treated animals, all other doses tested induced both a significant increase in kaolin intake and dose-dependent suppression of food intake. Furthermore, kaolin intake preceded the onset of the anorectic response for all anorectic doses tested.

In order to test whether kaolin consumption would impact the magnitude and/or temporal pattern of GDF15-induced anorexia, we delivered GDF15 at 0, 1, 10, 30, and 60 pmol i.c.v. into the 4th ventricle in lean rats that only had access to chow without kaolin and measured food intake and body weight over 72 h. Significant anorexia and body weight loss were observed with all doses that were previously shown to be anorectic in the presence of kaolin, and the onset and severity of anorexia was comparable to results in GDF15-treated animals with kaolin access (all p < 0.05; Figure S1).

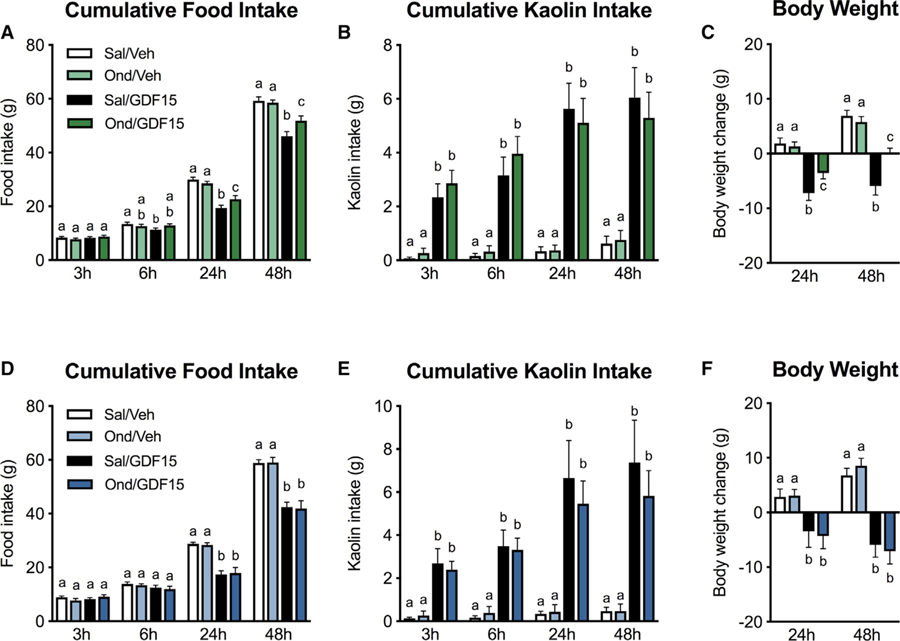

Systemic, but not Hindbrain, Ondansetron Partially Attenuates GDF15-Induced Anorexia

We then tested the ability of Ond to attenuate pica, anorexia, and the consequent body weight loss induced by GDF15. Systemic Ond pre-treatment by itself did not affect food intake nor body weight and did not stimulate kaolin intake compared to their relative controls (Figures 4A–4C), corroborating previous reports (Hayes and Covasa, 2006; Leon et al., 2019). Post hoc analysis revealed that systemic Ond pre-treatment was effective in attenuating GDF15-induced anorexia, leading to greater food intake compared to GDF15-treated animals at 24 h and 48 h, respectively. Furthermore, Ond treatment resulted in reduced body weight loss following GDF15 administration at both 24 and 48 h when compared to positive controls (Figure 4C). However, Ond failed to attenuate kaolin intake at any time points measured.

Figure 4. Systemic, but Not Hindbrain, Pharmacological Inhibition of 5-HT3R Signaling Attenuates GDF15-Induced Anorexia and Body Weight Loss.

(A and B) Systemic pre-treatment of the selective 5-HT3R antagonist Ondansetron (Ond, 1 mg/kg i.p., n = 13) attenuated anorexia (A), but failed to reduce kaolin consumption (B).

(C) Systemic Ond was also effective in attenuating GDF15-induced body weight loss.

(D–F) Ond i.c.v. pre-treatment (25 mg, n = 13) infused into the 4th ventricle did not prevent GDF15-induced anorexia (D), pica (E), and body weight loss (F).

Data expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed with a 2 × 2 repeated-measurements two-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey’s post hoc test. Means with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

We then investigated the specific contribution of hindbrain 5-HT3R receptor signaling by evaluating the effects of Ond-infused i.c.v. into the 4th ventricle on GDF15-induced pica and anorexia. Ond administered to the hindbrain at a dose of 25 µg 30 min prior to GDF15 delivery did not attenuate GDF15-induced kaolin intake nor anorexia at any time points measured (Figures 4D–4F).

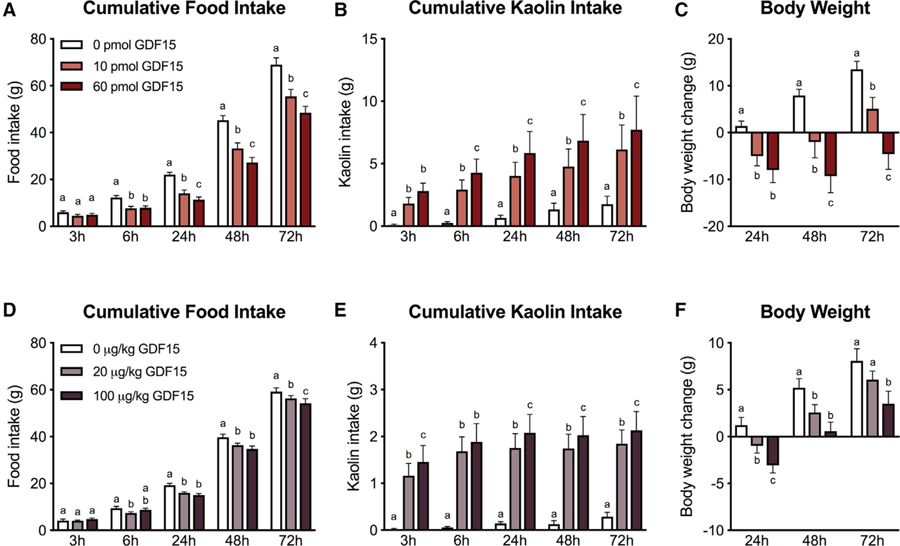

Central and Systemic Delivery of GDF15 Triggers Anorexia, Kaolin Intake, and Body Weight Loss in HFSD-Induced Obese Rats

To test whether GDF15 causes nausea/emetic-like behavior during weight loss in HFSD-induced obese rats, we measured kaolin consumption, food intake, and body weight changes in HFSD-induced obese rats following a dose response analysis of GDF15. 10 pmol and 60 pmol of GDF15 delivered i.c.v. into the 4th ventricle significantly suppressed food intake at 6, 24, 48 and 72 h post-administration in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A). On average, after 24 h, food intake was reduced by 8.0 ± 1.3 g for 10 pmol and 10.7 ± 0.8 g for 60 pmol, leading to 36% ± 5% and 49% ± 4% lower intake in GDF15-treated versus control animals. Kaolin intake was significantly higher for both doses at all measured time points relative to controls (Figure 5B). GDF15 i.c.v. administration into the 4th ventricle also dose-dependently induced net body weight loss 24 h post-injection, leading to changes in body weight that persisted at 48 and 72 h (Figure 5C). To test the effects of systemically delivered GDF15, a second cohort of HFSD-induced obese rats received 20 µg/kg GDF15, 100 µg/kg GDF15, or vehicle via i.p. delivery. Systemic GDF15 delivery induced anorexia in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5D). This resulted in an average reduction of 15% ± 3% for the 20 µg/kg and 20% ± 5% for the 100 µg/kg dose of GDF15. Systemic GDF15 delivery also dose-dependently produced a pica response (Figure 5E) with kaolin consumption becoming significant at 3 h for both doses relative to vehicle group. For both doses tested, anorexia was paralleled by body weight loss compared to controls (Figure 5F). Body weight relative to controls was significantly reduced at 24 and 48 h for both systemic doses of GDF15 and also at 72 h for the highest dose.

Figure 5. Central and Systemic Delivery of GDF15 Produces Anorexia, Pica, and Body Weight Loss in High-Fat/High-Sucrose Diet-Induced Obese Rats.

(A–C) Central administration of GDF15 (10 and 30 pmol into the 4th ventricle) dose-dependently induced anorexia (A), kaolin consumption (B), and body weight loss (C) in obese rats (n = 14) compared to vehicle treated animals.

(D–F) Consistent with the central route of delivery, systemic administration of GDF15 (20 and 100 µg/kg i.p.) to obese rats (n = 14) induced anorexia (D), kaolin intake (E), and body weight loss (F) in a dose-dependent fashion.

All data expressed as mean ± SEM. Data in (B and C) were analyzed with a repeated-measurements two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni’s post hoc test. Means with different letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05).

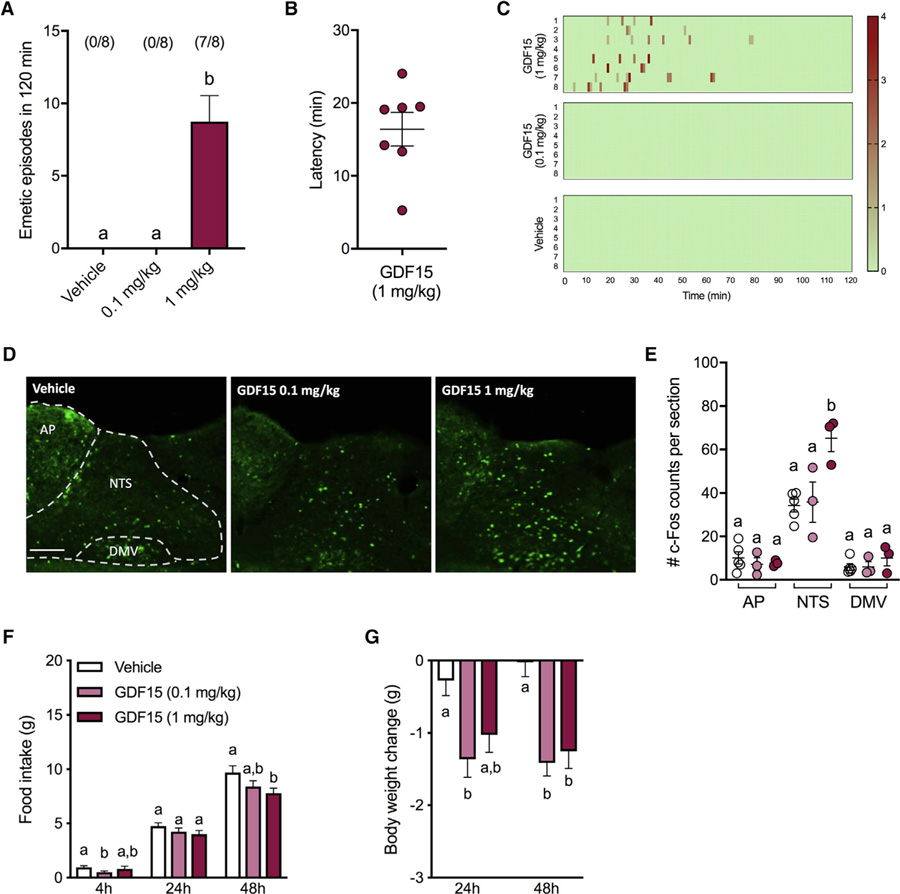

GDF15 Induces Emesis, Anorexia, Body Weight Loss, and c-Fos Expression in the AP/NTS in Shrews

To test whether exogenous GDF15 is an emetic stimulus, we used the musk shrew to examine the emetic response profile of different systemic doses of GDF15. The highest dose tested (1 mg/kg) induced emesis (Figure 6A) that occurred within minutes after administration (16.4 ± 2.3 min; Figure 6B). No emesis was triggered in 0.1 mg/kg or in vehicle treated animals. The pattern of the emetic responses is shown in Figure 6C. Figures 6D and 6E show that the highest dose GDF15 induced c-Fos expression in NTS but not in the AP or the dorsal motor vagus (DMV) compared to the lower dose and to vehicle treated animals (p < 0.01) 3 h after administration. No significant changes in c-Fos occurred in any region of the DMV of animals treated with 0.1 mg/kg compared to controls. Comparable c-Fos immunofluorescence in the NTS, AP, and DMV were analyzed and observed 90 min after GDF15 or vehicle administration (Figure S2). GDF15 administered at 1 mg/kg only reduced food intake (Figure 6F) and led to body weight loss at 48 h compared to vehicle (Figure 6G). No significant differences were noticed at earlier time points. The lower dose of GDF15 had a small but significant effect on 4 h food intake and induced body weight loss at 24 and 48 h relative to controls (all p < 0.05).

Figure 6. GDF15 Induces Severe Emesis and c-Fos Expression in the NTS but Mild Anorexia and Body Weight Loss in Shrews.

(A) In seven of the eight animals tested, 1mg/kg of GDF15 induced robust emetic responses that were not observed after 0.1 mg/kg GDF15 or saline injections.

(B) Graphical representation of latency to the first emetic episode of GDF15-treated animals that exhibited emesis.

(C) Heatmap showing latency, number of emetic episodes per minute for each animal across time.

(D) Representative immunofluorescent images showing c-Fos-positive neurons across in the dorsal vagal complex (250 µm rostral to the obex), 3 h after 1 mg/kg GDF15 (n = 3), 0.1 mg/kg GDF15 (n = 3), or vehicle (n = 5) i.p. injection.

(E) Systemic GDF15 administration at 1 mg/kg lead to a significantly higher number of c-Fos immunoreactive cells in the NTS of shrews 3 h after injection but not in the AP or DMV.

(F) GDF15 administered at 1 mg/kg only reduced food intake at 48 h while the lower dose of GDF15 had a minimal, yet significant, hypophagic effect at 4 h relative to controls. No significant differences were noticed at other time points.

(G) In line with the food intake data, the lower dose of GDF15 induced body weight loss at 24 and 48 h compared to vehicle. The highest dose tested induced significant body weight loss at 48 h.

Data in (A) were analyzed with repeated-measurements one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Data in (E) were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Data in (G and F) were analyzed with repeated-measurements two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. All data expressed as mean ± SEM. Means with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Scale bar, 100 µm.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this work was to examine whether GDF15-GFRAL induces nausea or emesis alongside anorexia. We report several key findings in our examination of anorexia, CFA, pica, and emesis, as well as further elucidate a role for GDF15-GFRAL signaling in chemotherapy-induced malaise using vomiting and non-vomiting mammalian animal models. Overall, this work supports the notion that nausea and emesis could be a component of the mechanism behind exogenous GDF15’s anorectic effect.

First, we sought to expand upon previously published work reporting that cisplatin triggered higher circulating GDF15 in mice and that GFRAL KO mice were insensitive to long-term anorexia and weight loss produced by cisplatin (Hsu et al., 2017). Our data showed robust cisplatin-induced elevation in plasma GDF15, with maximal increase within hours of treatment and remaining significantly elevated at least 3 days later. PF controls showed no changes in GDF15 levels, suggesting that the observed higher levels of GDF15 are not due to a general effect of stress and/or energy restriction, but are rather specific to cisplatin treatment. Further, GDF15 levels showed strong correlation to the percentage of anorexia, potentially indicating that it may be possible to predict the severity of anorectic response to cisplatin via endogenous circulating GDF15 as a biomarker, especially for those cancers not associated with elevated levels of GDF15 prior to chemotherapy, such as testicular cancer (Altena et al., 2015). However, cancers that are associated with elevated circulating GDF15 may complicate this theoretical predictive biomarker (see Tsai et al., 2018 for discussion). Nonetheless, it is likely that GDF15 may represent a promising signaling pathway to target poorly controlled chemotherapy-induced malaise, especially nausea (Aapro, 2018; Andrews and Horn, 2006; Horn et al., 2013).

Cisplatin induced c-Fos co-localized with GFRAL-positive neurons in the AP/NTS in mice, supporting our hypothesis that GFRAL-positive neurons are stimulated by cisplatin treatment, presumably via induction of peripheral GDF15 secretion. Although we did not directly test whether GFD15 release following cisplatin treatment plays a causal role in cisplatin-induced anorexia, we did detect elevated GDF15 during the same time window of the onset of cisplatin-induced emesis or emetic-like behavior in humans and animal models (Alhadeff et al., 2015; Hesketh et al., 2003; Rudd et al., 2018; Yamamoto et al., 2014). Data in GFRAL KO mice (Hsu et al., 2017) and in tumor models using a GDF15 antibody (Johnen et al., 2007) would suggest that blunting GDF15-GFRAL signaling would lead to reduced chemotherapy-induced malaise. We analyzed GDF15, TNF-α, and COX-2 transcripts in the liver, kidney, duodenum, and spleen, organs that are directly or indirectly susceptible to cytotoxic agents (Banerjee et al., 2018; Dasari and Tchounwou, 2014; Hanigan and Devarajan, 2003; Keefe et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2010), observing significantly higher GDF15, TNF-α, and COX-2 mRNA levels only in liver samples. The liver and kidney have been reported as potential sources of circulating GDF15 under non-pathological conditions (Böttner et al., 1999; Fairlie et al., 1999). Although it is possible that multiple organs and tissues contribute to the GDF15 rise in plasma, our data suggest the liver as a likely source of circulating GDF15 following cisplatin. Hepatic GDF15 production has also been linked to the increased levels of circulating GDF15 following sustained state of caloric excess as well as a consequence of acute nutritional stress (Patel et al., 2019), pointing to a key role of the liver in the GDF15 system.

We next sought to induce or detect sickness behavior(s) indicative of nausea or emesis in our models following GDF15 delivery. In rats, GDF15 delivered systemically or directly into the hindbrain was sufficient to induce pronounced kaolin intake within a few hours of delivery with effects that persisted for the duration of observed anorexia. In our first set of studies, we found that the central dose of GDF15 tested triggered a comparable CFA to what has been previously demonstrated following systemic administration in mice (Patel et al., 2019). The chosen dose induced an equivalent magnitude of CFA to that of a commonly used dose of LiCl in rats (Mietlicki-Baase et al., 2018). We observed induction of pica earlier than reductions in food intake, signifying that GDF15-induced nausea-like behaviors are likely present prior to observations of anorexia. To extend these findings and gain confidence in this notion, we performed additional dose response experiments in rats with or without access to kaolin in order to both test a range of doses of GDF15 and potentially ascertain whether kaolin access itself influenced either the time course or the magnitude of anorexia induced by GDF15. We found that rats given identical doses of GDF15 showed similar patterning (i.e., onset latency of anorexia and magnitude of food intake reduction) of anorexia whether kaolin was present or absent. It is possible that hunger signals “compete” with rising feelings of malaise across time in a dynamic, mechanistically separable manner to explain this temporal relationship of kaolin to food intake. In contrast, malaise could be a prerequisite of GDF15-induced anorexia. The somewhat “delayed” anorectic effect of GDF15 has been reported previously using a comparable paradigm (Yang et al., 2017) and is also consistent with the purported GDF15-mediated CACS mechanism in tumor models, which shows a delayed onset of anorexia and lean body mass loss, although, notably, effects are long-lasting once the phenotype occurs (Borner et al., 2016; Johnen et al., 2007). We also demonstrated that either systemic or hindbrain delivery of GDF15 caused similar effects in HFSD-induced obese rats, suggesting that weight loss achieved through GDF15-GFRAL-induced anorexia (i.e., as a means to potentially treat obesity) is also likely accompanied by persistent nausea and not dissociable from malaise.

Since 5-HT3R antagonists are considered a first-line therapeutic in antiemetic therapy for highly emetogenic chemotherapies like cisplatin (Aapro, 2005; Herrstedt, 2018), we tested whether the most commonly prescribed anti-emetic for chemotherapy patients, Ond (trade name Zofran), was able to significantly impact GDF15-induced anorexia and the consequent body weight loss. Our results showed that neither peripheral (i.e., systemic) nor central Ond pretreatment blocked GDF15-induced kaolin intake. These findings could indicate that cisplatin-induced GDF15 expression, release, and subsequent malaise may not be mediated by peripheral (i.e., vagal afferent) or hindbrain 5-HT3 receptors. In fact, cisplatin-induced kaolin intake and acute phase emesis are largely vagally mediated (De Jonghe and Horn, 2008; Sam et al., 2003), and more specifically via 5-HT3 receptors on vagal afferent (Andrews and Horn, 2006; Hesketh, 2008), which could explain separable mechanisms of action to produce malaise. Conversely, our work and others have shown that AP lesion blocks tumor-and GDF15-induced anorexia and cachexia while subdiaphragmatic vagal deafferentation has no effect, together suggesting direct action of GDF15 on the dorsal vagal complex (i.e., via GFRAL neuron activation within the AP/NTS) to exert its malaise effects (Borner et al., 2016; Tsai et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2017). We did, however, observe a significant partial attenuation of GDF15-induced anorexia by peripheral, but not hindbrain, Ond pretreatment at 24 h and 48 h. We believe this effect is likely due to secondary effects of Ond to reduce gastric emptying contributions to satiation (Hayes and Covasa, 2006) and perhaps partially restore disturbed gastric motility induced by GDF15 administration (Xiong et al., 2017). In general, Ond had only mild beneficial effects in preventing GDF15 actions, possibly explaining why chemotherapy-induced nausea, vomiting, and anorexia are still present in cancer patients despite Ond medication. This suggests a novel non-5-HT3R-dependent mechanism of chemotherapy-induced anorexia and malaise.

We also report that exogenous administration of GDF15 caused emesis. In our musk shrew model, GDF15 caused pronounced emesis within minutes of injection, as well as significant anorexia in the days following injection, the latter of which is consistent with published work on rodents from our lab and others (Emmerson et al., 2017; Hsu et al., 2017; Mullican et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2019; Xiong et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017). There is also a clear temporal difference in the occurrence of the first sign of malaise (i.e., emesis) and anorexia in the shrew, as emesis preceded the onset of anorexia by hours. Such results, in a non-rodent mammalian species, further corroborates our CFA and pica results in rats and strengthens our initial hypothesis that GDF15-induced anorexia, in part, could be driven by malaise. Furthermore, GDF15 induced c-Fos expression within the NTS of the shrew, providing immunohistological evidence of the engagement of brainstem emetic circuits by GDF15 in this model. GDF15-induced c-Fos in the NTS only occurred at doses that also triggered emesis (i.e.,1 mg/kg but not 0.1 mg/kg), supporting the hypothesis that activation in this region of the the brain is required for GDF15-induced emesis. No increase in c-Fos in the DMV and AP occurred after both GDF15 doses in the shrew. GDF15-induced c-Fos distribution within the dorsal vagal complex in the shrew appears to only partially overlap with observations of GDF15-induced c-Fos in mice (Frikke-Schmidt et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2014). It is difficult to draw direct comparisons across species with only intuitive assumptions of GFRAL expression or distribution within the shew hindbrain; however, our data in the vomiting shrew may suggest GFRAL to be differentially distributed within the hindbrain in a species-specific manner. Not only the AP, but also the NTS, is directly accessible by blood-borne mediators (Broadwell and Sofroniew, 1993), and neurons located in the caudal NTS contain a dense network of dendrites that also extends into the AP (Llewellyn-Smith et al., 2011). Hence, NTS neurons could be directly activated by GDF15, partially bypassing the AP, providing an explanation for species differences in c-Fos within the AP.

In summary, the data presented here illustrate that GDF15 administration causes emesis and feeding behaviors consistent with the induction of nausea in emetic and non-emetic mammalian models, respectively. It has been speculated that GDF15 could cause food aversion and malaise as part of the biological role of the peptide (Patel et al., 2019). We demonstrated GDF15-induced emesis and sickness behaviors which are consistent with the notion of GDF15 functioning as a (patho-) physiological signal associated with stimuli that induce sickness. It is important to make clear that emesis and food aversion are distinctive phenomena. It has been put forward and discussed that GDF15 could be named “Limosin” for its anorectic properties (Breit et al., 2017) or “aversin” for its potential role in food aversion (O’Rahilly, 2017). Based on our data, we would suggest including the emetic potential of GDF15 (e.g., “emetaversin”) when considering peptide nomenclature.3

Limitations of Study

Limitations of our work are that we do not show whether blockade of circulating GDF15 and antagonism of GFRAL reduces chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Future work directly testing the anti-emetic effects of GDF15 neutralizing antibodies or direct GFRAL receptor antagonism is crucial to ascertaining the utility of GDF15-GFRAL as a clinical target for emesis control. While we do show that GDF15 is an emetic stimulus, the shrew model does not have the readily available genetic tools available in rodents (i.e., genetic-based targeting approaches to reduce GDF15-GFRAL signaling) necessary to more precisely interrogate GDF15-GFRAL in this species. Data provided here necessitate that GDF15-induced emesis must be studied in multiple mammalian models capable of emesis to better understand the role of GDF15-GFRAL signaling in the generation of sickness.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

This study did not generate new unique reagents. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Bart De Jonghe (bartd@nursing.upenn.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Adult male wild type mice (n = 54 C57BL/6J, Jackson Laboratory) weighing ~22–27 g at arrival were individually housed in standard cages with access to standard chow diet (Purina LabDiet 5001) and to tap water ad libitum, except where noted.

Sprague Dawley rats (n = 107 Charles River) weighing ~270–300 g at arrival were individually housed in hanging wire mesh cages. Rats were fed ad libitum with standard chow diet (Purina LabDiet 5001) and had ad libitum access to tap water, except where noted. In the majority of behavioral paradigms, rats also had ad libitum access to kaolin pellets (Research Diets, K50001) for at least 5 d prior to the start of the experiment. In a separate group of animals, rats were exposed to high fat/high sucrose diet (HFSD, Research Diets, D12492) in addition to standard chow for 6 weeks prior testing. One week before the onset of treatment, standard chow was removed and replaced by kaolin. Rats were kept on HFSD for the entire experimental period.

Adult female shrews (n = 29, Suncus murinus) weighing ~35–45 g, were obtained from a source colony maintained by Dr. Charles Horn, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center (a Taiwanese strain derived from a stock supplied by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, laboratory of Dr. John Rudd). Shrews were single housed in plastic cages (37.3 × 23.4 × 14 cm, Innovive), fed ad libitum with a mixture of feline (75%, Laboratory Feline Diet 5003, Lab Diet) and ferret food (25%, High Density Ferret Diet 5LI4, Lab Diet) and had ad libitum access to tap water, except where noted.

All animals were healthy and disease-free, as well as naive to any experimental drug and test prior to the beginning of experiments. All animals were housed under a 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle in a temperature-and humidity-controlled environment (23 ± 1°C). All procedures were conducted as approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

METHOD DETAILS

Drugs and Route of Administration

For all central administrations, drugs were administered via intracerebroventricular (icv) infusions into the fourth ventricle in a 1 µl volume. All systemic (i.e., peripheral) treatments were delivered intraperitoneally (ip). Cisplatin (Cis, cis-diammineplatinum dichloride, Sigma-Aldrich, 15663–27-1) was dissolved in 0.9% saline (1 mg/2 mL volume) and administered at a dose of 10 mg/kg in mice and 6 mg/kg in rats; respectively. These doses of cisplatin were chosen based on previous studies within this range showing reliable induction of behavioral effects (De Jonghe et al., 2016). Central GDF15 (human recombinant, Biovision, cat. 4569) was administered at concentrations of 0, 1, 3, 10, 30 and 60 pmol/ml in 100% DMSO (Honeywell, cat. 34869–1L). For systemic treatments in shrews, GDF15 was dissolved in 5% DMSO saline solution and injected at 0.1 and 1 mg/kg (10 mL/kg). For systemic administration in rats, GDF15 was dissolved in saline solution (5 mM Acetate salt, 240 mM Propylene Glycol and 0.007% Polysorbate 20, pH 4) and injected at 20 and 100 µg/kg (1 mL/kg). The selective 5-HT3R antagonist Ondansetron (Ond; Sigma Aldrich, Cat. 103639–04-9)was either dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; Harvard Apparatus, Cat. 59–7316) for icv delivery (25 µg) or dissolved in 0.9% saline and injected at 1 mg/kg ip as previously described (Hayes and Covasa, 2006; Leon et al., 2019). LiCl (0.15 M in 0.9% saline, 20 mL/kg, Sigma Aldrich, Cat. L4408) was also injected ip (Leon et al., 2019).

General In Vivo Study Design

Animals were habituated to single housing in their home cage and received mock (no volume injected) ip and/or icv injections at least 1 wk prior to experimentation. Studies in mice were conducted between-subjects. All behavioral experiments in rats and shrews, except the conditioned flavor avoidance experiment in rats, used a within-subjects, Latin-square design, with each treatment separated by 72 h. The conditioned flavor avoidance experiment in rats was conducted using a between-subject fashion.

Stereotaxic Surgery in Rats

Rats received ip anesthesia cocktail (KAX, ketamine 90 mg/kg, Butler Animal Health Supply; xylazine 2.7 mg/kg, Anased; acepromazine 0.64 mg/kg, Butler Animal Health Supply). A 26-gauge guide cannula (8 mm 81C3151/Spc, Plastics One) directed at the fourth ventricle was implanted using the following coordinates: 2.5 mm anterior to the occipital suture and 7.2 mm ventral to skull surface, and affixed to the skull with screws and dental cement as previously published (De Jonghe et al., 2016). Metacam (meloxicam from Midwest Veterinary Supply; 2 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously immediately after surgery and for the 2 consecutive days. All rats were given 1 wk of postoperative recovery. To confirm cannula placement, blood glucose was measured following 5-thio-D-glucose (210 µg in 2 µL of artificial cerebrospinal fluid, Santa Cruz Biotech, Cat. 20408–97-3) infusion as described previously (Hayes et al., 2011). All rats, with the exception of 3, passed verification tests and were therefore included in the experiments.

Effects of a Single Cisplatin Injection on Feeding Behavior and GDF15 Signaling in Mice

To evaluate the long-term effects of a single cisplatin injection on energy metabolism and GDF15 blood levels, mice (n = 29; 26–30 g) were injected either with cisplatin (10 mg/kg) or saline prior to dark onset. To control for the potentially confounding effects of anorexia and body weight loss on GDF15 levels from cisplatin treatment, vehicle-treated animals were pair-fed (PF) to receive the same amount of food as was consumed the previous day by the Cis group. Food intake and body weight were measured daily. One, 3, and 7 d after the injection a subgroup of animals was euthanized for blood and tissue collection. Animals were injected with a lethal dose of KAX, blood was collected from the right ventricle and the animals were immediately transcardially perfused with 0.1 M PBS for 2 min. Kidney, liver, spleen, and duodenum were collected and samples were snap-frozen for subsequent mRNA analyses (see below). Animals were subsequently perfused for 2 min with 4% PFA (paraformaldehyde, in 0.1M PBS, pH 7.4, Boston Bioproducts, Cat. BM-155–500). Brains were then removed and post fixed in 4% PFA for 48 h and then stored in 30% sucrose for 2 d. Brains were frozen in cold hexane and stored at −20 °C until further processing. Six series of 10 mm-thick frozen coronal sections containing the dorsal vagal complex (DVC) were cut in a cryomicrotome (CM3050S, Leica Microsystem), slide-mounted (Superfrost Plus, VWR) and stored at −20 °C until further processing.

To investigate for acute changes in GDF15 levels occurring immediately after cisplatin administration, a subgroup of mice (n = 25; 26–30 g) was injected either with cisplatin (10 mg/kg) or saline prior to dark onset. Two, 6 and 24 h after injection, animals were euthanized with a lethal dose of KAX and blood was collected from the right ventricle and processed as described below.

Effects of 4th Ventricle GDF15 Delivery on Conditioned Flavor Avoidance (CFA)

Here, we assessed potential learned associations of GDF15 treatment versus vehicle treatment utilizing the two-bottle preference paradigm as described previously (Garcia et al., 1955; Mietlicki-Baase et al., 2015). Rats were habituated to restricted water access for 90 min/d, beginning ~2 h after light onset. Rats (n = 17, 300–350 g) were then assigned to one of three experimental conditions for CFA training: 30 pmol GDF15 icv (n = 7), 0.15 M LiCl ip (n = 6) or DMSO (n = 4). CFA training consisted of 2 d during which rats had access to two burettes containing the same flavor of unsweetened Kool-Aid during the fluid access period of 90 min (1.3 g Kool-Aid powder [cherry or grape, equally preferred by rats (Lucas and Sclafani, 1996), Kraft Food] in 1L water). Immediately after, rats were injected with their assigned drug or vehicle. Order of drug/vehicle exposure and paired flavors were counterbalanced. Each training day was followed by a day where tap water was available during the fluid access period. Two d after the final CFA training day, the animals were tested for expression of CFA by providing them access to both flavors (one per burette) and measuring intakes during the 90 min access period (burette sides switched at 45 min to minimize side preference).

GDF15 Effects on Food and Kaolin Consumption, and Body Weight in Rats

Kaolin intake (i.e., pica, a well-established as a model of nausea in rats (Andrews and Horn, 2006)) was measured in addition to food intake. Rats (n = 22, 350–400 g) received icv infusion into the 4th ventricle of 30 pmol GDF15 or vehicle. Food and kaolin intake were measured at 3, 6, 24 h post-injection and body weight was measured at 0 and 24 h.

Effects of Different Centrally Delivered GDF15 Doses on Food and Kaolin Intake in Rats

Rats (n = 10, 350–400 g) received icv infusions into the 4th ventricle of 0, 10, 30 and 60 pmol of GDF15. Food and kaolin intake were measured at 2, 4, 8, 24, 48 and 72 h post-injection and body weight was measured at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. In a second cohort of rats (n = 10, 350–400 g) the effects of lower doses of GDF15 (0, 1, 3 and 10 pmol) on food and kaolin intake were subsequently tested. Body weight was recorded at 0, 24, 48, 72 h, while food and kaolin intake were analyzed at 2, 4, 8, 24, 48 and 72 h after injection

Effects of Different Centrally Delivered GDF15 Doses on Feeding and Body Weight in Rats

Rats (n = 11, 380–420 g) received icv infusions into the 4th ventricle of 0, 1, 10, 30 and 60 pmol of GDF15. Food intake and body weight were measured at described above.

Effects of Systemic and Central GDF15 Delivery on Feeding, Kaolin Intake and Body Weight in HFSD-Induced Obese Rats

Rats (n = 14, 600–650 g) received icv infusions into the 4th ventricle of 0, 10 and 60 pmol of GDF15. Food and kaolin intake were measured at 3, 6, 24, 48 and 72 h post-injection and body weight was measured at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h. In a second cohort of rats (n = 14, 550–620 g) the effects of two systemic doses of GDF15 (0, 20, 100 µg/kg) on food and kaolin intake, and body weight were investigated. Body weight was recorded at 0, 24, 48, 72 h, while food and kaolin intake were analyzed at 3, 6, 24, 48 and 72 h after injection.

Effects of Systemic and Centrally Ondansetron Pre-treatments on GDF15 Effects in Rats

To evaluate the effects of 5-HT signaling in the mediation of GDF-15-induced anorexia and pica in a cohort of rats (n = 13, 400–500 g), Ond (1 mg/kg ip) or vehicle was administered 30 min before GDF15 infusion. To further explore the involvement of hindbrain 5-HT3 signaling on GDF15 actions, in a second cohort of animals (n = 13, 400–500 g) Ond was administered into the 4th ventricle 30 min before GDF15 delivery. In both experiments, food intake and kaolin consumption were measured at 3, 6, 24 and 48 h post-injection. Body weight were measured at 0, 24 and 48 h.

Emetic and Anorectic Properties of GDF15 in Shrews

Shrews (n = 8) were adapted to powdered food for 5 d and habituated to ip injections and to clear plastic observation chambers (23.5 × 15.25 × 17.8 cm) for two consecutive d prior to experimentation. Animals were injected ip with GDF15 (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) or vehicle 2 h before dark onset, then video-recorded (Vixia HF-R62, Canon, facing the longer side of the cage) for 120 min. After 120 min, the animals were returned to their cages. Each treatment was 72 h apart. Analysis of emetic episodes were measured by an observer blinded to treatment groups. Emetic episodes were characterized by strong rhythmic abdominal contractions associated with either oral expulsion from the gastrointestinal tract (i.e., vomiting) or without the passage of materials (i.e., retching movements). Latency to the first emetic episode, total number of emetic episodes, and number of emetic episodes per minute were calculated.

Food intake was evaluated using the De Jonghe laboratory’s custom-made, automated feedometers. To briefly describe the system, our feedometer arrays consist of a standard mouse cage (29 × 19 × 12.7 cm) with mounted food hoppers resting on a custom-cut conical plexiglass cup (to account for spillage) attached to a load-cell which is specially designed to capture shrew food intake based on our laboratory’s observation of the animals’ consummatory behavior. Shrews had ad libitum access to powdered food through a custom-designed circular (3 cm diameter) cylindrical port in the cage. Food weights were measured every 10 s to the nearest 0.1 g (Arduino 1.8.8). Data obtained from the feedometer were processed and converted by computer software (Processing 3.4 and Microsoft Excel) to determine food ingestion each 10 s and a total food intake curve was cumulated for 4, 12 and 24 h. Body weight was measured at 0, 24, and 48 h.

Quantification of GFRAL/c-Fos in the AP/NTS of Mice

Immunofluorescence processing of brain sections was conducted similarly as previously described (Hsu et al., 2017). For antigen retrieval, sections were left in 90°C citrate solution (Vector, H-3000) for 1 h. Slides were rinsed in 0.1M PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (0.1% PBST) for 5 min, then incubated in 0.1% PBST containing 5% normal donkey serum (NDS) for 30 min, followed by an overnight incubation with rabbit anti-Fos antibody (1:500; Cell Signaling, Cat. s2250) and with sheep anti-GFRAL antibody (1:500, Thermofisher, Cat. PA5–47769, in 0.1% PBST). After washing (3×15 min) with 0.1% PBST sections were incubated with the secondary antibody donkey anti-sheep Alexa Fluor 594 (1:500 in 5% NDS 0.1% PBST; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Cat. 713–585-003) and with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500 in 5% NDS 0.1% PBST; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Cat. 711–545-152) for 2 h at room temperature. After final washing (3×15 min in 0.1% PBST) the sections were coverslipped with Fluorogel (Electron Microscopy Sciences). A total of 3 DVC sections per animal were used to quantify the number of c-Fos and/or GFRAL labeled cells in the AP and NTS (approximately 200 mm rostral to the obex). c-Fos and GFRAL positive neurons were visualized and quantified in blind fashion using fluorescence microscopy (20x; Keyence BZ-X800).

Quantification of c-Fos in the Shrew AP/NTS

Shrews (n = 21) were injected ip with GDF15 (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) or vehicle at dark onset and then then sacrificed with a lethal dose of KAX 90 min and 3 h after injections. Shrews were then immediately transcardially perfused with 0.1 M PBS for 2 min and with 4% PFA for 2 min similarly as described above. Brains were removed and post fixed in 4% PFA for 48 h and then stored in 30% sucrose for two d. Brains were frozen in cold hexane and stored at −20° C until further processing. Three series of 30 µm-thick frozen coronal sections containing the DVC were cut in a cryomicrotome, stored in cryoprotectant at −20° C until further processing.

Immunofluorescence processing of shrew brain sections were performed according to our described procedures (Alhadeff et al., 2015). Briefly, free-floating sections were washed with PBS (3×8 min), incubated in 5% NDS 0.3% PBST for 1 h, followed by an overnight incubation with rabbit anti-Fos antibody (1:1000 in 5% NDS 0.3% PBST; s2250; Cell Signaling). After washing (3×8 min) with PBS, sections were incubated with the secondary antibody donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500 in 5% NDS 0.3% PBST; Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories, Cat. 711–545-152) for 2 h at room temperature. After final washing (3×8 min in 0.1M PBS), sections were mounted onto glass slides (Superfrost Plus, VWR) and coverslipped with Fluorogel (Electron Microscopy Sciences). A total of 3 DVC sections per animal were used to quantify c-Fos labeled cells in the AP and NTS (approximately 250 mm rostral to the obex). c-Fos positive neurons were visualized and quantified manually in blind fashion using fluorescence microscopy (20x; Keyence BZ-X800).

Blood Collection and GDF15 Measurements in Mice

Blood was collected in EDTA containing tubes (Sarstedt, Cat. 500 K3E) and centrifuged at 7000 × g (4° C, 7 min) to obtain plasma, which was stored in aliquots at −80° C for subsequent analysis. GDF15 levels were measured with using an ELISA (R&D Systems, Cat. MGD150) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Each sample was run in duplicate by an experimenter blinded to treatment.

mRNA Extraction and Gene Expression Assays

RNA was extracted and purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PureLink RNA Mini Kit, Life technologies, Cat. 12183025) by an experimenter blinded to treatment. cDNA was generated from the extracted RNA using the high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (iScript, Bio-rad, Cat. 1708891). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed using pre-designed Taqman probes (Thermofisher) and pre-made master mix (Fast Advanced Master Mix, Applied Biosystems, Cat. 4444554). Mouse beta-actin (Mm00607939, lot P180325–001) was used as housekeeping reference gene and the following probes were used to amplify GDF15 (Mm00442228, lot 1670789), TNF-α (Mm00443258, lot 1629748), and COX-2 (Mm03294838, lot 1635964) transcripts. The relative expression was calculated using the comparative delta-delta Ct method. Samples were run in duplicate.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Daily food intake, body weight, kaolin consumption, GDF15 levels, and c-Fos and GFRAL counts were expressed as mean ± SEM. Body weight changes were calculated by subtracting the weight of the animal at the day of injection from the body weight at 24, 48, and 72 h. Behavioral data were analyzed by a repeated-measures One-Way, Two-Way or 2 × 2 Two-Way ANOVAs, followed by Tukey’s or Bonferroni’s post hoc tests. For GDF15 levels ordinary Two-Way ANOVAs followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used. Gene expression (for kidney, duodenum and spleen) and immunohistological data were analyzed using the Student’s t test. Changes in hepatic gene expression over time were analyzed with an ordinary Two-Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test. For all statistical tests, a P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using Prism GraphPad 8.0.

Samples sizes were not pre-determined by power analysis but instead via investigator estimates based on our previous work on cisplatin and GDF15 effects in rodent models. In the experiments conducted using a between-subject design, animals were randomly allocated to their relative treatment conditions. Treatment order was randomly selected for all within-subjects work. All biological tissues/samples were processed in a blind fashion.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

The published article includes all data generated or analyzed during this study. No code was used or generated in this study.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Alexa fluor 488 Donkey Anti-Rabbit 1gG (H+L) | Jackson Immuno Research | CAT# 711–545-152; RRID: AB_2313584 |

| Alexa fluor 594 Donkey Anti-Sheep 1gG (H+L) | Jackson Immuno Research | CAT# 713–585-003; RRID: AB_2340747 |

| GFRAL sheep mAb | Thermofisher | CAT# PA5–47769; RRID: AB_2607220 |

| c-Fos 9F6 Rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling | CAT# s22505; RRID: AB_2247211 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Shrew brain | In house (University of Pennsylvania) | N/A |

| Mouse brain (C57BL/J9) | In house (University of Pennsylvania) | CAT# JAX:000664 |

| Mouse blood (C57BL/J9) | In house (University of Pennsylvania) | CAT# JAX:000664 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Cisplatin | Sigma Aldrich | CAT# 15663–27-1 |

| GDF15 human recombinant | Biovision | CAT# 4569 |

| DMSO | Honeywell | CAT# 34869–1L |

| Ondansetron | Sigma Aldrich | CAT# 103639–04-9 |

| aCSF | Harvard Apparatus | CAT# 59–7316 |

| 5-Thio-D-Glucose | Santa Cruz Biotech | CAT# 20408–97-3 |

| Kool Aid Powder | Kraft foods | N/A |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Fast Advanced Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | CAT# 4444554 |

| iScript | Bio-rad | CAT# 1708891 |

| RNA extraction kit PureLink RNA Mini Kit | Life technologies | CAT# 12183025 |

| GDF15 rodent ELISA kit | R&D Systems | CAT# MGD150 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Adult WT mice C57BL/J9 | Jackson Laboratories | CAT# JAX: 000664 |

| Sprague Dawley Rats | Charles River | CAT# CR: 001 |

| Adult shrews (Suncus murinus) | UPMC Hillman Cancer Center | CAT# N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| TNF-α Taqman probe | Thermofisher | CAT# Mm00443258, lot 1629748 |

| COX-2 Taqman probe | Thermofisher | CAT# Mm03294838, lot 1635964 |

| GDF15 Taqman probe | Thermofisher | CAT# Mm00442228, lot 1670789 |

| b-actin Taqman Probe | Thermofisher | CAT# Mm00607939, lot P180325–001 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GraphPad PRISM | GraphPad Software | RRID: SCR_000306 |

| Illustrator (CS6) | Abobe | RRID: SCR_010279 |

| Other | ||

| Standard lab diet (rodent) | Purina Lab Diet | CAT# 5001 |

| High fat/high sucrose diet (rodent) | Research diets | CAT# D12492 |

| Feline diet | PMI Lab Diets | CAT# 5003 |

| Ferret diet | PMI Lab Diets | CAT# 5L14 |

| Kaolin | Research Diets | CAT# 57–504 |

Highlights.

Chemotherapy-induced sickness involves GDF15

GDF15-GFRAL signaling causes emesis and nausea that precede the onset of anorexia

Anorexia triggered by GDF15 is associated with sickness in both lean and obese rats

GDF15-induced anorexia cannot be dissociated from GDF15-induced sickness

Context and Significance.

GDF15 has become a keen target for anti-obesity therapies. Here, Borner et al. show that reduced food intake resultant from GDF15 administration is accompanied by measures of nausea in the rat and vomiting in the shrew. In the mouse, the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin increases circulating GDF15 levels and triggers neuronal activity in the hindbrain. When considering the use of GDF15-based drugs for obesity treatment, the data shown here suggest that GDF15 induces a state of sickness as part of its mechanism of action to reduce food intake. Conversely, the blockade of GDF15 signaling may reduce nausea and vomiting in patients receiving treatments that stimulate GDF15 release, such as cancer treatment with emetogenic chemotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Lauren Stein, Samantha Fortin, Rinzin Lhamo, and Rosa Leon for technical assistance. We also thank Bernard B. Allan for sharing his immunofluorescence protocol for GFRAL. This work was supported by NIH DK-112812 (B.C.D.), NIH DK-115762 (M.R.H.), NIH DK-021397 (H.J.G. and M.R.H.), NIH CA-201962 (C.C.H.), SNF P2ZHP3_178114, and SNF P400PB_186728 (T.B.).

B.C.D. receives research funding from Eli Lilly & Co. and Pfizer, Inc. and provided remunerated consultancy services for cachexia-related projects for Pfizer, Inc., not supporting these studies. R.P.D. is a scientific advisory board member and received funds from Xeragenx LLC (St. Louis, NY) and Balchem, New Hampton, New York that were not used in support of these studies. M.R.H. receives research funding from Zealand Pharma, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly & Co., and Boehringer Ingelheim that was not used in support of these studies. H.J.G. is a consultant and advisory board member for Novo Nordisk and receives research support from Pfizer, Inc. that was not used to support these studies. T.B., M.R.H., B.C.D., and R.P.D. are co-inventors and owners of a patent for a proprietary compound related to the GDF15-GFRAL system (serial #: 62/801,391).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.12.004.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

No other competing interests are declared.

REFERENCES

- Aapro M. (2005). 5-HT(3)-receptor antagonists in the management of nausea and vomiting in cancer and cancer treatment. Oncology 69, 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aapro M. (2018). CINV: still troubling patients after all these years. Support. Care Cancer 26, 5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhadeff AL, Holland RA, Nelson A, Grill HJ, and De Jonghe BC. (2015). Glutamate Receptors in the Central Nucleus of the Amygdala Mediate Cisplatin-Induced Malaise and Energy Balance Dysregulation through Direct Hindbrain Projections. J. Neurosci 35, 11094–11104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhadeff AL, Holland RA, Zheng H, Rinaman L, Grill HJ, and De Jonghe BC. (2017). Excitatory Hindbrain-Forebrain Communication Is Required for Cisplatin-Induced Anorexia and Weight Loss. J. Neurosci 37, 362–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altena R, Fehrmann RS, Boer H, de Vries EG, Meijer C, and Gietema JA. (2015). Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) plasma levels increase during bleomycin-and cisplatin-based treatment of testicular cancer patients and relate to endothelial damage. PLoS ONE 10, e0115372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PL, and Horn CC. (2006). Signals for nausea and emesis: Implications for models of upper gastrointestinal diseases. Auton. Neurosci 125, 100–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Sinha K, Chowdhury S, and Sil PC. (2018). Unfolding the mechanism of cisplatin induced pathophysiology in spleen and its amelioration by carnosine. Chem. Biol. Interact 279, 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch E, Prestrud AA, Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Feyer PC, Somerfield MR, Chesney M, Clark-Snow RA, Flaherty AM, Freundlich B, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology (2011). Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol 29, 4189–4198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauskin AR, Brown DA, Kuffner T, Johnen H, Luo XW, Hunter M, and Breit SN. (2006). Role of macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 in tumorigenesis and diagnosis of cancer. Cancer Res 66, 4983–4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar RJ. (2018). Conditioned flavor preferences in animals: Merging pharmacology, brain sites and genetic variance. Appetite 122, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner T, Arnold M, Ruud J, Breit SN, Langhans W, Lutz TA, Blomqvist A, and Riediger T. (2016). Anorexia-cachexia syndrome in hepatoma tumour-bearing rats requires the area postrema but not vagal afferents and is paralleled by increased MIC-1/GDF15. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 8, 417–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttner M, Suter-Crazzolara C, Schober A, and Unsicker K. (1999). Expression of a novel member of the TGF-beta superfamily, growth/differentiation factor-15/macrophage-inhibiting cytokine-1 (GDF-15/MIC-1) in adult rat tissues. Cell Tissue Res 297, 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breit SN, Tsai VW, and Brown DA. (2017). Targeting Obesity and Cachexia: Identification of the GFRAL Receptor-MIC-1/GDF15 Pathway. Trends Mol. Med 23, 1065–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadwell RD, and Sofroniew MV. (1993). Serum proteins bypass the blood-brain fluid barriers for extracellular entry to the central nervous system. Exp. Neurol 120, 245–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning KN. (2015). Role of central vagal 5-HT3 receptors in gastrointestinal physiology and pathophysiology. Front. Neurosci 9, 413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, de Moor CA, Eisenberg P, Ming EE, and Hu H. (2007). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: incidence and impact on patient quality of life at community oncology settings. Support. Care Cancer 15, 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasari S, and Tchounwou PB. (2014). Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol 740, 364–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe BC, and Horn CC. (2008). Chemotherapy-induced pica and anorexia are reduced by common hepatic branch vagotomy in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 294, R756–R765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe BC, and Horn CC. (2009). Chemotherapy agent cisplatin induces 48-h Fos expression in the brain of a vomiting species, the house musk shrew (Suncus murinus). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 296, R902–R911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe BC, Holland RA, Olivos DR, Rupprecht LE, Kanoski SE, and Hayes MR. (2016). Hindbrain GLP-1 receptor mediation of cisplatin-induced anorexia and nausea. Physiol. Behav 153, 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmerson PJ, Wang F, Du Y, Liu Q, Pickard RT, Gonciarz MD, Coskun T, Hamang MJ, Sindelar DK, Ballman KK, et al. (2017). The metabolic effects of GDF15 are mediated by the orphan receptor GFRAL. Nat. Med 23, 1215–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T, Minami M, Hirafuji M, Ogawa T, Akita K, Nemoto M, Saito H, Yoshioka M, and Parvez SH. (2000). Neurochemistry and neuropharmacology of emesis-the role of serotonin. Toxicology 153, 189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie WD, Moore AG, Bauskin AR, Russell PK, Zhang HP, and Breit SN. (1999). MIC-1 is a novel TGF-beta superfamily cytokine associated with macrophage activation. J. Leukoc. Biol 65, 2–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyer P, and Jordan K. (2011). Update and new trends in antiemetic therapy: the continuing need for novel therapies. Ann. Oncol 22, 30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frikke-Schmidt H, Hultman K, Galaske JW, Jørgensen SB, Myers MG Jr., and Seeley RJ. (2019). GDF15 acts synergistically with liraglutide but is not necessary for the weight loss induced by bariatric surgery in mice. Mol. Metab 21, 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, Kimeldorf DJ, and Koelling RA. (1955). Conditioned aversion to saccharin resulting from exposure to gamma radiation. Science 122, 157–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, Geling O, Hansen M, Cruciani G, Daniele B, De Pouvourville G, Rubenstein EB, and Daugaard G. (2004). Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer 100, 2261–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanigan MH, and Devarajan P. (2003). Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: molecular mechanisms. Cancer Ther 1, 47–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MR, and Covasa M. (2006). Gastric distension enhances CCK-induced Fos-like immunoreactivity in the dorsal hindbrain by activating 5-HT3 receptors. Brain Res 1088, 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MR, Leichner TM, Zhao S, Lee GS, Chowansky A, Zimmer D, De Jonghe BC, Kanoski SE, Grill HJ, and Bence KK. (2011). Intracellular signals mediating the food intake-suppressive effects of hindbrain glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation. Cell Metab 13, 320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrstedt J. (2018). The latest consensus on antiemetics. Curr. Opin. Oncol 30, 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh PJ. (2008). Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N. Engl. J. Med 358, 2482–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh PJ, Van Belle S, Aapro M, Tattersall FD, Naylor RJ, Hargreaves R, Carides AD, Evans JK, and Horgan KJ. (2003). Differential involvement of neurotransmitters through the time course of cisplatin-induced emesis as revealed by therapy with specific receptor antagonists. Eur. J. Cancer 39, 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn CC, Henry S, Meyers K, and Magnusson MS. (2011). Behavioral patterns associated with chemotherapy-induced emesis: a potential signature for nausea in musk shrews. Front. Neurosci 5, 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn CC, Kimball BA, Wang H, Kaus J, Dienel S, Nagy A, Gathright GR, Yates BJ, and Andrews PL. (2013). Why can’t rodents vomit? A comparative behavioral, anatomical, and physiological study. PLoS ONE 8, e60537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JY, Crawley S, Chen M, Ayupova DA, Lindhout DA, Higbee J, Kutach A, Joo W, Gao Z, Fu D, et al. (2017). Non-homeostatic body weight regulation through a brainstem-restricted receptor for GDF15. Nature 550, 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnen H, Lin S, Kuffner T, Brown DA, Tsai VW, Bauskin AR, Wu L, Pankhurst G, Jiang L, Junankar S, et al. (2007). Tumor-induced anorexia and weight loss are mediated by the TGF-beta superfamily cytokine MIC-1. Nat. Med 13, 1333–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe DM, Brealey J, Goland GJ, and Cummins AG. (2000). Chemotherapy for cancer causes apoptosis that precedes hypoplasia in crypts of the small intestine in humans. Gut 47, 632–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley PW. (2009). Nausea and vomiting in people with cancer and other chronic diseases. BMJ Clin. Evid 2009, 2406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon RM, Borner T, Reiner DJ, Stein LM, Lhamo R, De Jonghe BC, and Hayes MR. (2019). Hypophagia induced by hindbrain serotonin is mediated through central GLP-1 signaling and involves 5-HT2C and 5-HT3 receptor activation. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 1742–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YL, Malik N, Sanger GJ, Friedman MI, and Andrews PL. (2005). Pica–a model of nausea? Species differences in response to cisplatin. Physiol. Behav 85, 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Reimann F, Gribble FM, and Trapp S. (2011). Preproglucagon neurons project widely to autonomic control areas in the mouse brain. Neuroscience 180, 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas F, and Sclafani A. (1996). Capsaicin attenuates feeding suppression but not reinforcement by intestinal nutrients. Am. J. Physiol 270, R1059–R1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki N, Ueno S, Kaji T, Ishihara A, Wang CH, and Saito H. (1988). Emesis induced by cancer chemotherapeutic agents in the Suncus murinus: a new experimental model. Jpn. J. Pharmacol 48, 303–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mietlicki-Baase EG, Reiner DJ, Cone JJ, Olivos DR, McGrath LE, Zimmer DJ, Roitman MF, and Hayes MR. (2015). Amylin modulates the mesolimbic dopamine system to control energy balance. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 372–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mietlicki-Baase EG, Liberini CG, Workinger JL, Bonaccorso RL, Borner T, Reiner DJ, Koch-Laskowski K, McGrath LE, Lhamo R, Stein LM, et al. (2018). A vitamin B12 conjugate of exendin-4 improves glucose tolerance without associated nausea or hypophagia in rodents. Diabetes Obes. Metab 20, 1223–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullican SE, and Rangwala SM. (2018). Uniting GDF15 and GFRAL: Therapeutic Opportunities in Obesity and Beyond. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 29, 560–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullican SE, Lin-Schmidt X, Chin CN, Chavez JA, Furman JL, Armstrong AA, Beck SC, South VJ, Dinh TQ, Cash-Mason TD, et al. (2017). GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and the ligand promotes weight loss in mice and nonhuman primates. Nat. Med 23, 1150–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rahilly S. (2017). GDF15-From Biomarker to Allostatic Hormone. Cell Metab 26, 807–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LA. (2014). Conditioned flavor avoidance and conditioned gaping: rat models of conditioned nausea. Eur. J. Pharmacol 722, 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Alvarez-Guaita A, Melvin A, Rimmington D, Dattilo A, Miedzybrodzka EL, Cimino I, Maurin AC, Roberts GP, Meek CL, et al. (2019). GDF15 provides an endocrine signal of nutritional stress in mice and humans. Cell Metab. 29, 707–718.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd JA, Chan SW, Ngan MP, Tu L, Lu Z, Giuliano C, Lovati E, and Pietra C. (2018). Anti-emetic Action of the Brain-Penetrating New Ghrelin Agonist, HM01, Alone and in Combination With the 5-HT3 Antagonist, Palonosetron and With the NK1 Antagonist, Netupitant, Against Cisplatin-and Motion-Induced Emesis in Suncus murinus (House Musk Shrew). Front. Pharmacol 9, 869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sam TS, Cheng JT, Johnston KD, Kan KK, Ngan MP, Rudd JA, Wai MK, and Yeung JH. (2003). Action of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and dexamethasone to modify cisplatin-induced emesis in Suncus murinus (house musk shrew). Eur. J. Pharmacol 472, 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff AC, Bock AJ, Becker C, Kempf T, Wollert KC, and Davidson B. (2010). Growth differentiation factor-15 as a prognostic biomarker in ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol 118, 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland A, Naessens K, Plugge E, Ware L, Head K, Burton MJ, and Wee B. (2018). Olanzapine for the prevention and treatment of cancer-related nausea and vomiting in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 9, CD012555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai VW, Manandhar R, Jørgensen SB, Lee-Ng KK, Zhang HP, Marquis CP, Jiang L, Husaini Y, Lin S, Sainsbury A, et al. (2014). The anorectic actions of the TGFβ cytokine MIC-1/GDF15 require an intact brainstem area postrema and nucleus of the solitary tract. PLoS ONE 9, e100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai VWW, Husaini Y, Sainsbury A, Brown DA, and Breit SN. (2018). The MIC-1/GDF15-GFRAL Pathway in Energy Homeostasis: Implications for Obesity, Cachexia, and Other Associated Diseases. Cell Metab 28, 353–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Matsuki N, and Saito H. (1987). Suncus murinus: a new experimental model in emesis research. Life Sci 41, 513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Laar ES, Desai JM, and Jatoi A. (2015). Professional educational needs for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): multinational survey results from 2388 health care providers. Support. Care Cancer 23, 151–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Juan LV, Ma X, Wang D, Ma H, Chang Y, Nie G, Jia L, Duan X, and Liang XJ. (2010). Specific hemosiderin deposition in spleen induced by a low dose of cisplatin: altered iron metabolism and its implication as an acute hemosiderin formation model. Curr. Drug Metab 11, 507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Walker K, Min X, Hale C, Tran T, Komorowski R, Yang J, Davda J, Nuanmanee N, Kemp D, et al. (2017). Long-acting MIC-1/ GDF15 molecules to treat obesity: Evidence from mice to monkeys. Sci. Transl. Med 9, eaan8732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Asano K, Tasaka A, Ogura Y, Kim S, Ito Y, and Yamatodani A. (2014). Involvement of substance P in the development of cisplatin-induced acute and delayed pica in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol 171, 2888–2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Chang CC, Sun Z, Madsen D, Zhu H, Padkjær SB, Wu X, Huang T, Hultman K, Paulsen SJ, et al. (2017). GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and is required for the anti-obesity effects of the ligand. Nat. Med 23, 1158–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The published article includes all data generated or analyzed during this study. No code was used or generated in this study.