Abstract

The toxic effects of alcohol consumption are dependent upon its metabolism in the liver to downstream metabolites: acetaldehyde, acetate and acetyl-CoA. Recently in Nature, Mews et al. (2019) have discovered that acetyl-CoA derived from alcohol plays an important epigenetic role in regulating ethanol’s effects on the brain through histone acetylation.

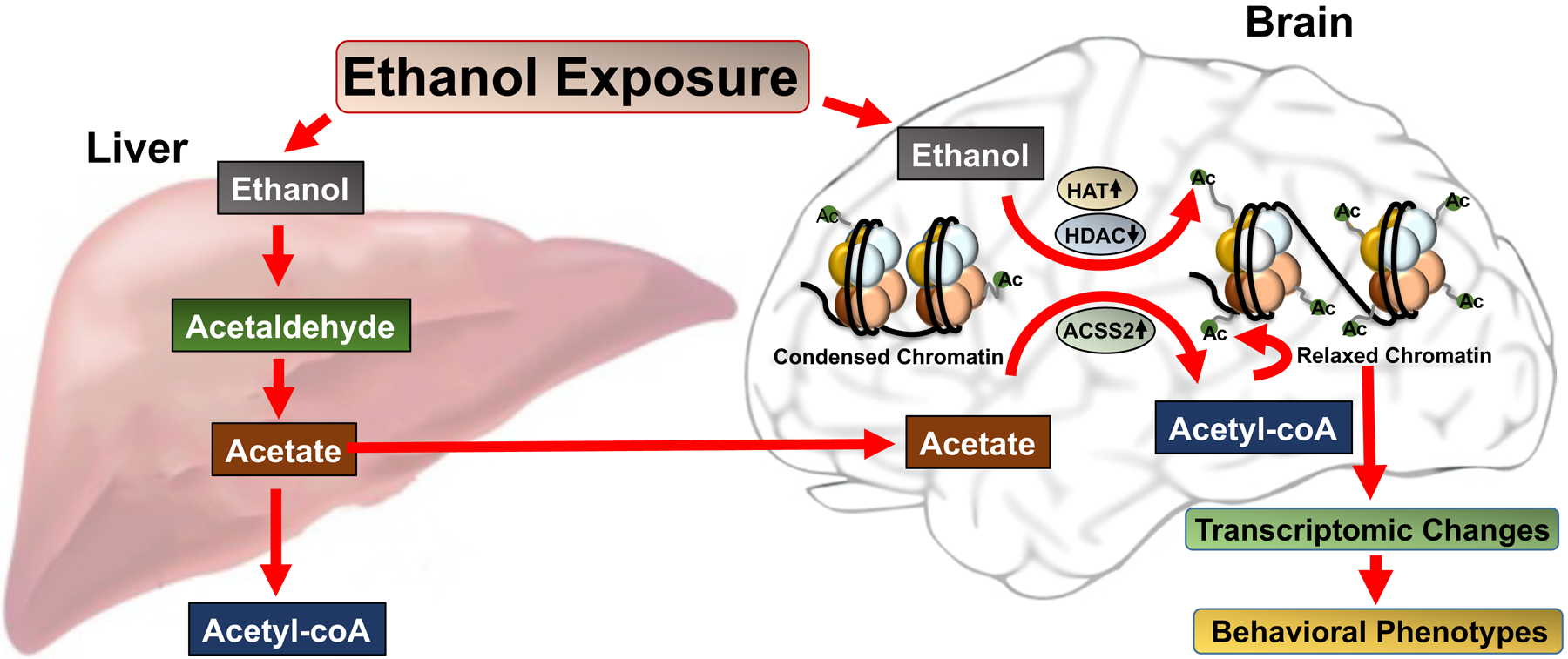

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a major global health concern (Peacock et al., 2018). There are considerable efforts being made to identify new molecular targets within the brain for the development of more effective therapies to treat this addictive disorder. As an approach in this direction, new research by Mews et al. (2019) published recently in Nature has demonstrated that the tertiary metabolite of alcohol (acetyl-CoA) is important in regulating ethanol’s effects in the brain and serves as a substrate in directly promoting histone acetylation, thereby regulating gene expression in the neurons and alcohol-related behaviors (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Alcohol metabolism in the liver and its impact on chromatin remodeling via transportation of acetate to the brain and its conversion to acetyl-CoA by ACSS2 leading to increased histone acetylation (Ac). Alcohol can also directly increase histone acetylation via inhibition of HDACs and activation of HATs. These epigenetic changes produced by ethanol or its metabolite, acetate, can produce relaxed chromatin leading to transcriptomic changes that regulate ethanol-related behavioral phenotypes.

Ethanol metabolism has previously been identified as an important factor in the toxic effects produced by ethanol consumption (Cederbaum, 2012). Ethanol is metabolized to acetyl-CoA through a three-step process, starting first with the oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase IB in the liver (Cederbaum, 2012). Other tissue-specific enzymes, such as alcohol dehydrogenase IA, are also important in this step. Acetaldehyde is then converted to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, which is the rate limiting step of alcohol metabolism. Finally, acetic acid is converted to Acetyl-CoA, where it enters the citric cycle and can be released as H2O and CO2. Acetaldehyde is a highly reactive species that induces oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and cytokine formation(Guo and Ren, 2010). Furthermore, build-up of acetaldehyde is often found in heavy drinkers, and individuals without functioning aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 have vasodilation, nausea and dysphasia when alcohol is consumed (Cederbaum, 2012; Guo and Ren, 2010). Efforts to capitalize on this effect as a deterrent to alcohol consumption resulted in the use of disulfiram (Antabuse) in the clinic to limited efficacy. Furthermore, ethanol has been shown to affect a staggeringly large number of different organ systems (notably the liver and brain) and a substantial number of different cell-transduction pathways, including epigenetic processes (Cederbaum, 2012; Choudhury and Shukla, 2008; Pandey et al., 2017). Chronic ethanol exposure is known to contribute to many of the negative physiological symptoms of withdrawal (Koob and Volkow, 2016; Pandey et al., 2017).

Histone acetylation is one of the most studied epigenetic processes that controls gene transcription (Pandey et al., 2017). The effects of acute ethanol on the epigenome via histone acetylation appear to be involved in anxiolytic effects (Pandey et al., 2017). Several previous studies have demonstrated that acute ethanol has the ability to activate histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs) in the brain (Pandey et al., 2017; Figure 1). These properties may lead to increased histone acetylation (active epigenetic marks) that produces chromatin remodeling and changes in gene expression in the amygdala, a brain region responsible for comorbidity of anxiety and AUD (Pandey et al., 2008, 2017). Previous research has demonstrated that different alcohols and their metabolites can also induce changes to histone acetylation in hepatocytes (Choudhury and Shukla, 2008).

Mews et al. has suggested that acetate coming from the liver directly binds to neuronal chromatin (Figure 1) and is then converted to acetyl-CoA via chromatin-bound acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2) (Mews et al., 2019). This appears to be another fascinating epigenetic mechanism involved in the action of ethanol. The current research elegantly combines metabolomics and RNA and ChIP sequencing to show that alcohol contributes to histone acetylation in the mouse brain. Using liquid-chromatography mass-spectrometry, the authors demonstrate that a single intraperitoneal injection of deuterated ethanol into mice rapidly increases histone acetylation in the dorsal hippocampus (dHPC) and prefrontal cortex (as well as the liver) and this increase lasts about 8 hours. The authors further demonstrate that this is regulated by chromatin-bound acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2). Interestingly, alcohol exposure produces more H3K9ac and H3K27ac peaks in dHPC at the genome-wide level, which is prevented by the knockdown of ACSS2.This manipulation also prevents ethanol conditioned place preference, suggesting that ACSS2 is required for ethanol reward learning, and provides more experimental evidence that epigenetic mechanisms are required for learning and memory. Previous studies have shown that learning and memory crucially rely on histone deacetylase-2 mediated epigenetic processes (Guan et al., 2009), and this new evidence creates a clearer picture about how ethanol facilitates its rewarding properties via ACSS2 dependent histone acetylation (Mews et al., 2019).

Since both ethanol and its secondary metabolite are known to be involved in changes in gene expression, the authors also evaluated if there was significant overlap between genes upregulated by the addition of acetate (ex vivo) and ethanol (in vivo) using RNA-sequencing. There was substantial overlap between genes induced by acetate and ethanol (830 genes). An additional 1010 genes were upregulated by ethanol and 2783 upregulated by acetate, suggesting that there are also effects of ethanol that are independent of an acetate-induced mechanism. While the authors did perform gene ontology (GO)-analysis on genes induced by acetate, it would also be interesting to see what GO-analysis was involved for genes that overlapped with exposure to ethanol and exposure to acetate. Also, it would be interesting to examine if acetate has any direct effects on other epigenetic players responsible for histone acetylation changes in the brain, such as HATs and HDACs.

Transgenerational epigenetic regulation by drugs of abuse has been an area of intense study, particularly in the field of alcohol abuse (Chastain and Sarkar, 2017). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) occurs when the fetus is harmed during prenatal alcohol exposure. The authors demonstrate that maternal exposure to alcohol also causes changes in histone acetylation in the fetal brain, and this may contribute to the distinctive facial features, learning disabilities and psychiatric symptoms that characterize this disorder by causing epigenetic dysregulation of tightly controlled developmental pathways (Mews et al., 2019).

In summary, this study helps to answer questions regarding how acute ethanol increases histone acetylation and contributes significantly to our understanding of epigenetic regulation produced by alcohol drinking. Previous studies have indicated that histone deacetylase pathways are crucial in alcohol withdrawal and dependence, and could be acting as a responsive mechanism for epigenetic reprogramming (Pandey et al., 2008, 2017). Several key questions remain, specifically how an ACSS2-dependent histone acetylation mechanism contributes to the withdrawal aspects and ethanol tolerance that are observed in both animal models of alcohol dependence and in clinical populations. It would be interesting to see an expansion of this research to explore these topics.

Acknowledgements:

SCP is supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants UO1AA-019971, U24AA-024605 [Neurobiology of Adolescent Drinking in Adulthood (NADIA) project], RO1AA-010005, P50AA-022538 (Center for Alcohol Research in Epigenetics), and by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA merit grant I01BX004517 & Senior Research Career Scientist award). JPB is supported by a fellowship F32 AA027410 grant. Authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Cederbaum AI (2012). Alcohol metabolism. Clinics in Liver Disease 16, 667–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastain LG, and Sarkar DK (2017). Alcohol effects on the epigenome in the germline: Role in the inheritance of alcohol-related pathology. Alcohol 60, 53–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury M, and Shukla SD (2008). Surrogate alcohols and their metabolites modify histone H3 acetylation: Involvement of histone acetyl transferase and histone deacetylase. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res 32, 829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J-S, Haggarty SJ, Giacometti E, Dannenberg J-H, Joseph N, Gao J, Nieland TJF, Zhou Y, Wang X, Mazitschek R, et al. (2009). HDAC2 negatively regulates memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Nature 459, 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R, and Ren J (2010). Alcohol and acetaldehyde in public health: From marvel to menace. IJERPH 7, 1285–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, and Volkow ND (2016). Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry 3, 760–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mews P, Egervari G, Nativio R, Sidoli S, Donahue G, Lombroso SI, Alexander DC, Riesche SL, Heller EA, Nestler EJ, et al. (2019). Alcohol metabolism contributes to brain histone acetylation. Nature 574, 717–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Ugale R, Zhang H, Tang L, and Prakash A (2008). Brain chromatin remodeling: A novel mechanism of alcoholism. Journal of Neuroscience 28, 3729–3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Kyzar EJ, and Zhang H (2017). Epigenetic basis of the dark side of alcohol addiction. Neuropharmacology 122, 74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, Colledge S, Hickman M, Rehm J, Giovino GA, West R, Hall W, Griffiths P, et al. , (2018). Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction 113, 1905–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]