Abstract

A 61-year-old man presented with fever, shortness of breath, and new chest pain. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed Brugada-like ECG pattern. Emergent coronary angiography demonstrated normal coronary arteries. He was subsequently diagnosed with COVID-19. After a few days he felt better and the ECG Brugada-like pattern resolved.

Key Words: chest pain, COVID-19, ECG, fever, STEMI

Abbreviations and Acronyms: COVID-19, coronavirus disease-2019; ECG, electrocardiogram

Graphical abstract

A 61-year-old man presented with fever, shortness of breath, and new chest pain…

History of Presentation

A 61-year-old Hispanic man presented to the emergency department with a 5-day history of shortness of breath and substernal chest pain. He had felt febrile and generally ill over the past few days but had not taken his temperature. On presentation, he was febrile (38.5°C), hypertensive (156/81 mm Hg), tachycardic (121 beats/min), and tachypneic (28 breaths/min).

Past Medical History

His past medical history was significant for hepatitis C, dermatitis, and obesity. The patient did not report history of syncope, and there was no family history of sudden cardiac death.

Investigations

Laboratory data demonstrated mild hyponatremia (132 mmol/l), potassium (4.0 mmol/l) and magnesium (2.5 mmol/l) in the normal range, and mild hypocalcemia (8.3 mmol/l). The C-reactive protein level was 150.7 mg/l, and the brain natriuretic peptide level was 19 pg/ml. The remaining laboratory values were unremarkable, and the troponin level was normal. His medications included clobetasol and triamcinolone ointments. The portable chest radiograph showed multifocal bilateral interstitial and airspace opacities with a normal cardiac silhouette (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Portable Chest Radiograph Demonstrating a Diffuse Bilateral Interstitial Pattern

AP = anteroposterior.

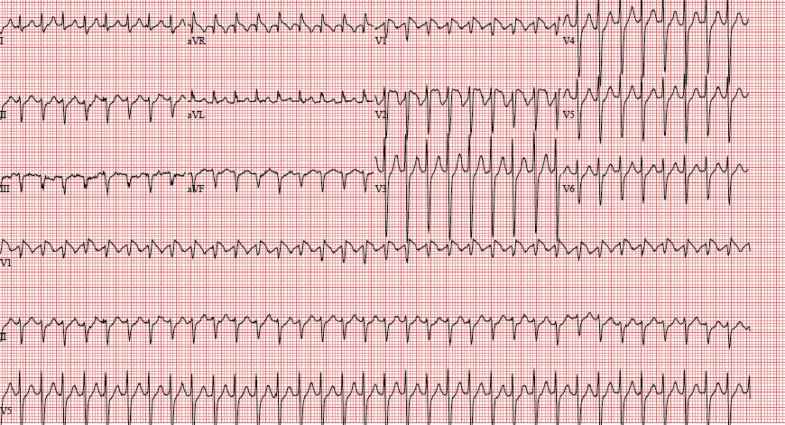

The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a Brugada-type pattern in the right precordial leads with no reciprocal changes (Figure 2). A bedside echocardiogram demonstrated a mildly depressed global ejection fraction. On the basis of the clinical constellation of symptoms, along with the reduced ejection fraction and ST-segment elevation, we proceeded with emergency coronary angiography.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram Demonstrating Brugada Type I Pattern

Note the absence of reciprocal changes.

Diagnostic coronary angiography performed through the right radial approach revealed angiographically normal coronary arteries (Figures 3 and 4). Ventriculography confirmed the globally mildly reduced ejection fraction.

Figure 3.

Angiographically Normal Dominant Right Coronary Artery

Figure 4.

Angiographically Normal Left Coronary System

Management

The patient was admitted to a dedicated coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) intensive care unit. The COVID-19 results became available within 24 h and were positive. His condition continued to improve, and he required minimal supplemental oxygen to maintain arterial saturation. All serial troponin values were negative. Two days later he developed a brief episode of supraventricular tachycardia that was successfully terminated with intravenous adenosine (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Electrocardiogram Demonstrating Narrow Complex Tachycardia With Brugada Type I Pattern

Four days after the initial presentation, he was doing well without fever. The C-reactive protein level had decreased to 25.4 mg/l, and the ECG demonstrated nearly complete resolution of the initial Brugada-like ECG pattern (Figure 6). The patient was discharged to home after the 1-week hospital stay.

Figure 6.

Electrocardiogram Demonstrating Resolution of Brugada-Like Pattern in Right Precordial Leads

Discussion

Diagnosis and treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic present multiple diagnostic and logistic challenges (1). Myocardial injury, myocarditis, acute coronary syndromes, and arrhythmias have all been described in the setting of COVID-19 infection (2). ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads and Brugada-like ECG patterns have previously been associated with various conditions (e.g., fever, myocarditis toxicity, metabolic disorders, certain drugs). These Brugada-like patterns usually disappear once the inciting event is removed (3). A Brugada-like ECG pattern presents an additional diagnostic and therapeutic challenge because it may be seen in patients presenting with chest pain, thus mimicking ST-segment elevation. Atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, such as developed in our patient, has similarly been associated with Brugada syndrome (4). Most recently, COVID-19 infection has been described as unmasking Brugada syndrome in a patient who presented with syncope (5).

Conclusions

Our case is important because it demonstrates the need to differentiate between the Brugada syndrome and the Brugada-like ECG configuration. Given that our patient had a COVID-19–associated Brugada ECG pattern with no history of syncope, observation therapy was recommended because the risk of major adverse cardiac events is low (6).

Footnotes

Dr. Vidovich has received royalty payments from Merit Medical; and has received a research grant from Boston Scientific (neither relationship is relevant to the contents of this paper).

The author attests they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Case Reportsauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Tam C.-C.F., Cheung K.-S., Lam S. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e006631. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Driggin E., Madhavan M.V., Bikdeli B. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2352–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baranchuk A., Nguyen T., Ryu M.H. Brugada phenocopy: new terminology and proposed classification. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2012;17:299–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2012.00525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasdemir C., Payzin S., Kocabas U. High prevalence of concealed Brugada syndrome in patients with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1584–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang D., Saleh M., Garcia-Bengo Y., Choi E., Epstein L., Willner J. COVID-19 infection unmasking Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm Case Reports. 2020;6:237–240. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Khatib S.M., Stevenson W.G., Ackerman M.J. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:e91–e220. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]