Abstract

Objective:

To examine whether history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) is associated with age of onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in three racial/ethnic groups.

Methods:

Data from 7577 non-Hispanic Caucasian, 792 African-American, and 870 Hispanic participants with clinically-diagnosed AD were obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC). Participants were categorized by presence/absence of self-reported remote (>1 year prior to diagnosis of dementia due to AD) history of TBI with or without loss of consciousness (LOC; TBI+ vs. TBI−). Any group differences in education, sex, APOE ε4 alleles, family history of dementia, or history of depression, stroke, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes were included in analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) comparing clinician-estimated age of AD symptom onset between TBI+ and TBI− groups.

Results:

Clinician-estimated onset of AD occurred 2.3 years earlier for non-Hispanic Caucasians (F=33.72, df=1,7697, P<.001) and 3.4 years earlier for African-Americans (F=5.17, df=1,772, P=.023) in subjects with a history of TBI with LOC. In the Hispanic cohort, females with a history of TBI with LOC had AD onset 5.8 years earlier compared to females without TBI with LOC (F=6.96, df=1,865, P=.008), while TBI history in Hispanic males showed similar ages of AD onset.

Conclusion:

History of TBI with LOC was associated with a 2-3 year earlier onset in non-Hispanic Caucasian and African-American groups and a nearly 6 year earlier onset in Hispanic females, while no association was observed in Hispanic males. This is the first study to examine whether history of TBI is associated with AD onset in minorities. Further work in traditionally underserved populations is needed to understand possible underlying mechanisms for these differences.

Keywords: head injury, minorities, Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

History of moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been linked to the development of neurodegenerative conditions including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) {1}and all-cause dementia {1-3}. Some studies suggest TBI may be associated with accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques {4,5}and neurofibrillary tangles {5}, and that TBI with loss of consciousness is associated with earlier age of Alzheimer’s onset by 2.5–3.5 years {6,7}. Still, the mechanism by which TBI increases the risk and earlier onset of AD dementia is unknown, and may involve the initiation or acceleration of a neurodegenerative process, and/or lowering cognitive or neuronal reserve (for a detailed review, see {8}). However, not all studies have found a significant association between TBI and AD or dementia {9,10}, and more investigations are needed to determine mechanisms and specific groups that may be more at risk of AD after TBI.

Previous studies on the long-term effects of TBI and pathology/dementia due to AD are largely comprised of Caucasian samples, despite accelerating growth of the minority population in the U.S. {11}. Additionally, Hispanic and African American populations have a higher prevalence of AD than non-Hispanic Caucasians, with rates 1.5 and 2 times higher {12,13}. Hispanic ethnicity has been associated with a higher risk of earlier AD onset {14} and African-Americans have been identified to have a higher risk of developing AD, both relative to non-Hispanic Caucasians {11}. Recently, a small sample of Mexican Americans (n=22) have shown greater severity of cognitive impairment/comorbid depression, at initial visit to a memory disorders clinic compared to a non-Mexican cohort {15}. While factors such as education, gender, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes have been associated with this increased risk, TBI as a risk factor for dementia in minority populations in general have yet to be explored {16}. Because a history of TBI has been linked to an increased risk for earlier onset of AD and related conditions in primarily Caucasian samples{6,7,8, and 17}, examining whether a similar association is found in individuals of Hispanic ethnicity may have implications for improving our understanding of dementia onset in these traditionally understudied populations.

The present study aimed to assess estimated age of AD onset between those with and without a history of TBI among three racial/ethnic cohorts (African-American, non-Hispanic Caucasian, and Hispanic), while also evaluating the influence of other potential dementia risk factors including: education, gender, stroke history, depression history, number of Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 alleles, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and family history of AD.

Methods

Participants.

Data were obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) uniform data set (UDS). The UDS has been aggregating sociodemographic, clinical, and medical information data on adults with subjective memory concerns, mild cognitive impairment, and various neurodegenerative dementias since 2005 from NIA-funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADRC) nationwide. Written informed consent was obtained from participants at each ADRC and approved by the ADRC’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Research using the NACC database was approved by the University of Washington IRB. Data for the current study were derived from 32 ADRCs across the United States from September 2005 to March 2015. NACC UDS Versions 1 and 2 were exclusively used to maintain consistent TBI criteria across samples. Inclusion criteria for the current study were: 1) age ≥ 50 years; 2) clinically diagnosed with dementia due to AD at an initial or follow-up ADRC visit; and 3) had available data on self-reported race and ethnicity, TBI history, and clinician-estimated age of cognitive symptom onset. A multidisciplinary team of clinicians reached a consensus diagnosis of AD using standardized criteria. Diagnosis of AD was made according to NINCDS/ADRDA {18}criteria. Race and Ethnicity were gathered through subject and informant report, and groups were categorized as non-Hispanic Caucasian, African-American, and Hispanic.

Measures.

A history of TBI was defined by combining several variables within the NACC dataset. In NACC UDS Versions 1 and 2, subjects and informants were asked if the subject had ever sustained a TBI with a loss of consciousness (LOC) lasting < 5 minutes, ≥ 5 minutes, or if the injury resulted in chronic deficit or dysfunction. Each of these responses was coded as recent/active (i.e., occurred within the past year or still required active management) remote/inactive (i.e., occurred more than 1 year ago but was resolved or with no current treatment underway), or absent. In UDS Versions 1 and 2, date of injury was not available aside from greater or less than 1 year prior to the visit. Because < or ≥ 5 minutes of LOC is an arbitrary cut-off that does not follow any clinically established guidelines for severity, we combined these variables into TBI with any duration of LOC. To minimize the possibility that recent injuries impacted the subject’s diagnosis of dementia, we only included those who sustained a TBI w/LOC more than one year prior to their diagnosis of dementia and had no chronic cognitive deficits from injury (TBI+). Those who reported an absence of a history of TBI w/LOC during their ADRC visits were included as the comparison group (TBI−).

Available clinical data to guide diagnosis of dementia included information gathered from the subject/informant, medical records (i.e., neuropsychological/neurological exam findings, detailed medical history, and/or observation. Clinician estimated age of onset of dementia due to AD was guided by clinical judgement informed by temporal correlation of the totality of the aforementioned data. The age of onset was estimated when the subject was first diagnosed with AD (regardless of dementia status). Therefore, all patients were diagnosed with dementia due to AD either at the first visit or in subsequent visits. Because several risk factors for AD have been shown to have varying prevalence rates among different racial and ethnic groups, we evaluated whether gender, education, number of APOE ε4 alleles, family history of dementia, or history of depression, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, or stroke, could have a potential influence on the age of onset between the TBI+ and TBI− groups. History of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and stroke were coded in NACC as absent, recent/active, or remote/inactive, and were dichotomized into present (recent or remote) or absent conditions for this study. Depression and family history of dementia (i.e., 1st-degree relative) was coded as absent, present, or unknown in the NACC database. Depression was defined in NACC as having been diagnosed with a mood disorder using DSM-IV-TR/DSM-5 criteria (major depression, dysthymia, or bipolar disorder), evaluated by a clinician for depressed mood, or prescribed an anti-depressant medication.

Statistical Analysis.

Analyses were conducted separately for the three cohorts of non-Hispanic Caucasians, African-Americans, and Hispanics. Independent samples t-tests and Chi-Square analyses, where appropriate, evaluated whether TBI+ and TBI− groups differed in years of education, sex, number of APOE ε4 alleles, family history of dementia, or history of depression, stroke, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes. Variables having significant differences were entered as covariates in the primary analyses. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVAs) were used to assess if dementia onset differed between TBI+ and TBI− groups, and we assessed for interactions between TBI history and any covariate within the ANCOVA models. If a significant interaction was found, the model was run as a 2×2 ANCOVA. Levene’s test was used to assess for equality of variances between groups. If significant, non-parametric Welch analysis of variance (ANOVAs) were used to assess if significant differences remained after accounting for unequal variances. Missing data were excluded case-wise for each individual analysis. Level of significance was set at P < .05 for all analyses, and carried out using IBM Statistics V24 (IBM Corp, SPSS Statistics V24, Armonk, New York, U.S.A., 2013).

Results

A total of 9,683 subjects met initial inclusion criteria. Eighty nine percent of informant reports came from a close family member (57% spouses/partners, 30% children, and 2% siblings). Eighty four percent of individuals were diagnosed with dementia secondary to AD at the first visit or eventually diagnosed with AD (16%). Missing data for the entire sample were as follows: stroke (N=36, <1%), depression (N=110, 1%), APOE ε4 alleles (N=2319, 24%), diabetes (N=22, <1%), hypertension (N=23, <1%), hypercholesterolemia (N=100, 1%), years of education (N=80, <1%). The final sample size for the non-Hispanic Caucasian cohort included 669 subjects (9.6%) with a history of TBI with LOC (TBI+) and 6908 without a history of TBI with LOC (TBI−). In the African-American cohort, 46 subjects (6.2%) had a reported history of TBI with LOC and 746 did not. Finally, in the Hispanic cohort, 60 participants (7.4%) reported a TBI with LOC and 810 did not.

Within the non-Hispanic Caucasian cohort, significant differences were found between the TBI+ and TBI− groups in years of education (P=.021), sex (P<.001), and remote depression (P=.011). Significant group differences in sex (P=.008) and number of APOE ε4 alleles (P=.029) were found within the African-American cohort. Additionally, within the Hispanic cohort, significant group differences were found in education (P=.011; See Table 1).

Table 1:

Sample characteristics and group differences by TBI history

| Characteristic | Non-Hispanic Caucasians | African-Americans | Hispanic | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI+ | TBI− | TBI+ | TBI− | TBI+ | TBI− | ||||||||||

| N | % | N | % | P value | N | % | N | % | P value | N | % | N | % | P value | |

| Males | 455 | 67 | 3245 | 46 | <.001** | 28 | 46 | 353 | 30 | .008* | 32 | 53 | 253 | 31 | <.001** |

| Education, M | 15.25 | - | 14.97 | - | .021* | 13.1 | - | 12.7 | - | 0.396 | 11.25 | - | 9.58 | - | .011* |

| Education, SD | 3.1 | - | 3.04 | - | - | 3.76 | - | 3.53 | - | - | 5.18 | - | 4.93 | - | - |

| Stroke | 39 | 6 | 362 | 5 | 0.475 | 3 | 5 | 130 | 11 | 0.135 | 3 | 5 | 65 | 8 | 0.412 |

| Rec. Dep. | 275 | 41 | 2803 | 40 | 0.739 | 21 | 35 | 405 | 35 | 0.94 | 30 | 50 | 403 | 51 | 0.933 |

| Rem. Dep. | 154 | 23 | 1309 | 19 | .011* | 11 | 14 | 160 | 18 | 0.331 | 16 | 27 | 180 | 23 | 0.469 |

| APOE ε4 | 0.972 | .029* | 0.903 | ||||||||||||

| 0 Alleles | 239 | 42 | 2258 | 41 | 18 | 39 | 266 | 36 | 21 | 53 | 288 | 53 | |||

| 1 Alleles | 259 | 45 | 2500 | 46 | 16 | 35 | 366 | 50 | 15 | 38 | 208 | 39 | |||

| 2 Alleles | 76 | 13 | 733 | 13 | 12 | 26 | 98 | 13 | 4 | 10 | 43 | 8 | |||

| Diabetes | 68 | 10 | 663 | 10 | 0.639 | 15 | 25 | 292 | 25 | 0.987 | 17 | 28 | 200 | 25 | 0.54 |

| HTN | 320 | 47 | 3381 | 48 | 0.64 | 45 | 74 | 909 | 77 | 0.597 | 41 | 68 | 498 | 62 | 0.297 |

| XOL | 356 | 53 | 3581 | 52 | 0.529 | 28 | 46 | 574 | 49 | 0.617 | 30 | 51 | 426 | 54 | 0.699 |

| Family Hx. Dementia | 376 | 60 | 3934 | 62 | 0.546 | 31 | 55 | 563 | 58 | 0.66 | 33 | 67 | 393 | 59 | 0.246 |

Note: TBI = traumatic brain injury. Rec. Dep. = recent depression. Rem. Dep. = remote depression. HTN = hypertension. XOL = hypercholesterolemia.

= P<.05.

= P<.001.

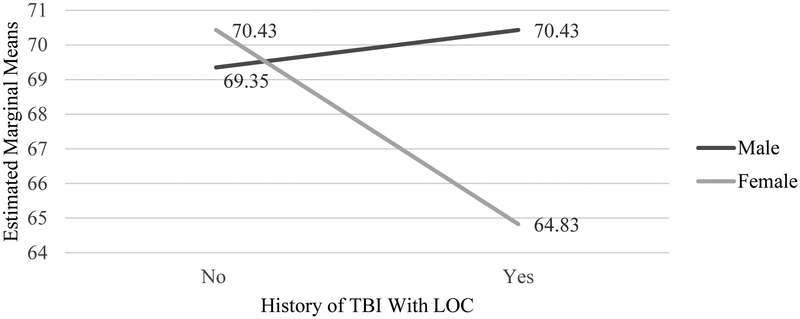

A series of ANCOVAs were carried out to assess whether estimated AD onset differed between TBI+ and TBI− groups in each cohort. In the non-Hispanic Caucasian cohort, onset of AD occurred 2.3 years earlier for the TBI+ group than the TBI− group (F=30.492, df=1,7572, P<.001). However, Levene’s test revealed a violation in the assumption of homogenous variances; thus, a non-parametric Welch ANOVA was conducted, and a significant difference between TBI +/− groups remained (F=29.32, df=1,7697, P<.001). Similarly, in the African-American cohort, results showed a 3.37-year earlier AD onset for the TBI+ group than the TBI− group (F=5.17, df=1,772, P=.023; See Table 2). In the Hispanic cohort, a significant interaction was observed between sex and TBI history (F=6.96, df=1,865, P=.008), revealing that females with TBI had a 5.78 year-earlier AD onset compared to females without TBI, but little difference was observed for males with and without a TBI history (See Figure 1). No other significant interactions were observed between TBI group and covariates in any racial/ethnic cohort (P’s > .05).

Table 2:

Main effect differences in age of dementia onset in participants with and without a history of TBI by race/ethnicity cohort.

| Ethnicity | TBI Hx | N | M | SD | M-difference | F | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | TBI+ | 669 | 68.53 | 9.5 | 2.3 | 30.49 | <.001** |

| TBI− | 6908 | 70.83 | 10.3 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic African American | TBI+ | 46 | 69.11 | 8 | 3.37 | 5.17 | .023* |

| TBI− | 730 | 72.48 | 8.6 | ||||

| Hispanic | TBI+ | 60 | 67.63 | 9.8 | 2.48 | 3.16 | .076 |

| TBI− | 810 | 70.11 | 9.4 |

Note: TBI Hx = TBI history. TBI = traumatic brain injury. Covariates for non-Hispanic Caucasian cohort include: gender, remote depression (> 2 years prior to first ADRC visit), and education. Covariates for African-Americans include: gender and number of Apoe4 alleles, and covariates for Hispanic cohort include: gender and education.

= P<.05.

= P<.001.

Figure 1. Sex interaction in age of dementia onset in participants with and without a history of TBI in Hispanic cohort.

Note: AD = Alzheimer’s disease. TBI = traumatic brain injury. LOC = loss of consciousness. Covariates: years of education.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the risk for earlier AD onset after TBI among different racial and ethnic groups. We found that a TBI history with LOC was associated with a 2–3 years earlier onset of symptoms for both the non-Hispanic Caucasian and African American groups. While this association is similar to previous findings in samples with mild cognitive impairment {17} and autopsy-confirmed AD {6}, those studies were predominantly non-Hispanic Caucasian (≥ 80%). Thus, the present study suggests the risk for earlier onset of AD is comparable for non-Hispanic Caucasians and African Americans with history of TBI with LOC. This adds to a growing literature indicating TBI might be linked with accelerated aging or earlier onset of dementia secondary to AD. However, in the Hispanic group, a history of TBI with LOC was associated with a nearly 5 year earlier onset in females, but not in males. It is possible that Hispanic females possess some genetic factor(s) leading to a vulnerability to TBI effects, and protective factors in Hispanic males may offset any effects from a history of TBI, though several other factors may be contributing to this relationship.

It is possible that Hispanic females in this sample may be more prone to earlier AD onset after TBI due to a combination of factors related to the interaction of cultural factors with seeking treatment from medical care providers, unique TBI risk factors, and socioeconomic standing. In a small subset of patients who presented to a memory disorders clinic, Mexican-Americans presented later in the course of dementia and with greater co-morbid depressive symptoms in comparison to Caucasians, but clinical rating of dementia severity was similar to Caucasians {15}. These findings could be due to Hispanics presenting to clinical attention with greater cognitive impairment but similar functional ratings by clinicians, possibly due to a mediating factor of family support. For a review of the influence of social/familial/financial factors on Hispanics wellbeing please see {19}. Another potential contributor to our findings in the Hispanic cohort may be more severe/frequent head injuries, which could not be examined further in the present study, as well as factors that impede seeking healthcare after injuries. A national survey {20} found 15.6% of Latino women endorsed history of intimate partner violence (IPV), which is supported by findings that long term Hispanic and mixed raced couples had the highest rates of IPV {21}. This is within the range of lifetime prevalence of IPV in US females, which is estimated at 25%. However, nationwide rates of IPV in females in Mexico was significantly higher at 45% {22}. Female victims of IPV are at higher risk for repetitive TBI with LOC {23}, and the possibility of hypoxia secondary to strangulation {24}. Thus, Hispanic women may be more likely to sustain more frequent and/or more severe TBI, which may put them at higher risk of earlier AD onset post-injury. Additionally, the intersection of sex and cultural factors (i.e., Marianismo-where women are taught to be modest, virtuous, and faithful/subordinate to their husbands) could have impacted self-reported history of TBI, partially accounting for the difference in the Hispanic cohort.

Finally, income disparities may make Hispanic females less likely to receive health care, and/or have the health literacy required to enact lifestyle changes (i.e., physical exercise) to reduce their risk of dementia. This study added education as a covariate, but no data on income and occupational status were available in the dataset. However, due to the lack of available data on age, chronicity, and severity of injury, or socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, it is unknown whether these factors might be contributing to our findings. Additionally, these factors do not account for the lack of significant findings in Hispanic males versus non-Hispanic males. Clearly, future study of dementia risk factors among Hispanic cohorts is needed.

Despite our significant preliminary findings, our study had several limitations. First, the sample sizes of the Hispanic and African American groups with a history of TBI were small, which may affect generalizability. As previously noted, the temporal relationship of reported TBI and cognitive impairment is confounded by the possibility that a head injury may have occurred following the onset of cognitive impairment {6}, and unfortunately date of injury is not recorded in UDS Versions 1 and 2. However, to minimize the possibility that the TBI occurred after onset of cognitive impairment and to reduce the possibility that TBI confounded the diagnosis of dementia., we included those only with remote (> 1 year prior to visit) injuries without reported chronic deficits. Other limitations include self-report of TBI and lack of TBI characteristics (i.e., severity, post-traumatic amnesia, etc.), although it is likely that injuries were milder in this study given the lack of reported chronic deficits. Significant heterogeneity may exist in the Hispanic cohort, such as level of acculturation, bilingualism, generation, and age of immigration, which could have impacted our findings.

Despite limitations, this is the first known study to approach TBI history as a risk factor for earlier AD onset in racially and ethnically diverse cohorts, and produced intriguing preliminary findings related to sex differences within the Hispanic cohort. The authors are cognizant of the potential for our hypotheses regarding these observed differences to be interpreted as an overextension of the data. After careful consideration we have decided that the benefit of highlighting these concerns is greater than the cost of perpetuating the invisibility of crucial factors in an increasingly racially/culturally diverse world. An obvious need exists for national databases to include specific information regarding TBI (i.e., date of injury, injury characteristics, severity, etc.) and important cultural variables (i.e., acculturation level, degree of bilingualism, etc.) along with in-depth collection of psychosocial information and lifestyle factors to promote more diversity- focused research in this area {25}.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by the UT Southwestern Alzheimer’s Disease Center (NIH P30 AG12300) and the Texas Alzheimer’s Research and Care Consortium (TARCC). The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADRCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

References

- 1.Plassman BL, Havlik RJ, Steffens DC, et al. Documented head injury in early adulthood and risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Neurology. 2000;55(8):1158–1166. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.8.1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raj R, Kaprio J, Korja M, Mikkonen ED, Jousilahti P, Siironen J. Risk of hospitalization with neurodegenerative disease after moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury in the working-age population: A retrospective cohort study using the Finnish national health registries Brohi K, ed. PLOS Med. 2017;14(7):e1002316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner RC, Burke JF, Nettiksimmons J, Kaup A, Barnes DE, Yaffe K. Dementia risk after traumatic brain Injury vs nonbrain trauma: The role of age and severity. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(12):1490–1497. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott G, Ramlackhansingh AF, Edison P, et al. Amyloid pathology and axonal injury after brain trauma. Neurology. 2016;86(9):821–828. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Widespread tau and amyloid-beta pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathol. 2012;22(2):142–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00513.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaffert J, LoBue C, White CL, et al. Traumatic brain injury history is associated with an earlier age of dementia onset in autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2018;32(4):410–416. doi: 10.1037/neu0000423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LoBue C, Denney D, Hynan LS, et al. Self-reported traumatic brain injury and mild cognitive impairment: Increased risk and earlier age of diagnosis Abisambra J, ed. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(3):727–736. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LoBue C, Cullum CM, Didehbani N, et al. Neurodegenerative dementias after traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;30(1):7–13. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17070145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Dams-O’Connor K, et al. Association of traumatic brain injury with late-life neurodegenerative conditions and neuropathologic findings. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(9):1062–1069. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dams-O’Connor K, Gibbons LE, Bowen JD, McCurry SM, Larson EB, Crane PK. Risk for late-life re-injury, dementia and death among individuals with traumatic brain injury: A population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(2):177–182. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vega IE, Cabrera LY, Wygant CM, Velez-Ortiz D, Counts SE. Alzheimer’s disease in the Latino community: Intersection of genetics and social determinants of health Abisambra J, ed. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(4):979–992. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H-Y, Panegyres PK. The role of ethnicity in Alzheimer’s disease: Findings from the C-PATH online data repository. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;51(2):515–523. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alzheimer’s Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(4):459–509. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27570871. Accessed March 15, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitten LJ, Ortiz F, Fairbanks L, et al. Younger age of dementia diagnosis in a Hispanic population in southern California. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(6):586–593. doi: 10.1002/gps.4040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Schiffer RB, Sutker PB. Presentation of Mexican Americans to a memory disorder clinic. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2007;29(3):137–140. doi: 10.1007/s10862-006-9042-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayeda ER, Karter AJ, Huang ES, Moffet HH, Haan MN, Whitmer RA. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Dementia Risk Among Older Type 2 Diabetic Patients: The Diabetes and Aging Study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(4):1009–1015. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LoBue C, Wadsworth H, Wilmoth K, et al. Traumatic brain injury history is associated with earlier age of onset of Alzheimer disease. Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;31(1):85–98. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2016.1257069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6610841. Accessed April 15, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monserud MA, Wong R. Depressive symptoms among older Mexicans: The role of widowhood, gender, and social integration. Res Aging. 2015;37(8):856–886. doi: 10.1177/0164027514568104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabina C, Cuevas CA, Zadnik E. Intimate Partner Violence among Latino Women: Rates and Cultural Correlates. J Fam Violence. 2015;30(1):35–47. doi: 10.1007/s10896-014-9652-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caetano R, Vaeth PAC, Ramisetty-Mikler S. Intimate partner violence victim and perpetrator characteristics among couples in the United States. J Fam Violence. 2008;23(6):507–518. doi: 10.1007/s10896-008-9178-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia. Panorama de Violencia Contra Las Mujeres En Los Estados Unidos Mexicanos.; 2011. www.inegi.org.mx. Accessed September 26, 2018.

- 23.Zieman G, Bridwell A, Cárdenas JF. Traumatic brain injury in domestic violence victims: A retrospective study at the Barrow Neurological Institute. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(4):876–880. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray CE, Lundgren K, Olson LN, Hunnicutt G. Practice update: What professionals who are not brain injury specialists need to know about intimate partner violence-related traumatic brain injury. Trauma, Violence, Abus. 2016;17(3):298–305. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seaton EK, Gee GC, Neblett E, Spanierman L. New directions for racial discrimination research as inspired by the integrative model. Am Psychol. 2018;73(6):768–780. doi: 10.1037/amp0000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]