Abstract

Background

HIV-positive kidney transplant (KT) recipients have similar outcomes to HIV-negative recipients. However, HIV-positive patients with advanced kidney disease might face additional barriers to initiating the KT-evaluation process. We sought to characterize comorbidities, viral control and management, viral resistance, and KT evaluation appointment rates in a cohort of KT evaluation-eligible HIV-positive patients.

Methods

We included patients seen between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2015 at a primary care HIV clinic who met KT-evaluation eligibility by an estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤ 20 ml/min/1.73 meters2 or dialysis-dependence. The primary outcome was a documented appointment for KT evaluation.

Results

Of 3735 patients evaluated at the HIV primary clinic during the study period, 42 (1.6%) were KT evaluation-eligible patients. The median age was 47 years, 77% were male, and 95%, black. Median CD4 count was 328 cells/mm3 (IQR 175–461). Among the 63% percent with anti-retroviral therapy (ART) prescription, 40% had viral loads > 200 copies. Among patients with HIV resistance profiles (50%, n=21), 52% had resistance to at least one class of ART. A majority (60%, n = 25) were scheduled for KT-evaluation appointment, but of those, only 8% (n = 2) had evidence of appointments before dialysis-dependence. Those without appointments had more schizophrenia (29% vs. 4%, p = 0.02), resistance (78% vs. 33%, p = 0.04), ART prescription (76% vs. 48%, p = 0.04), and more kidney disease of unknown etiology (53% vs. 8%, p = 0.02).

Conclusion

KT evaluation-eligible HIV-positive patients had a high rate of evaluation appointments, but a low rate of preemptive evaluation appointments. Schizophrenia and viral resistance disproportionally affected patients without evaluation appointments. These data precede the recommendation for universal ART for all HIV+ patients, regardless of CD4 count and viral load, and must be interpreted in the context of this limitation.

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that more than 7000 dialysis-dependent patients in the United States (US) are HIV-positive.1–6 Compared to their HIV-negative counterparts, HIV-positive patients on dialysis suffer higher morbidity and mortality.7,8 Fortunately, outcomes of kidney transplantation (KT) among HIV-positive patients have improved dramatically in recent years, with overall patient and allograft survival rates similar to those of HIV-negative KT recipients.9,10

However, HIV-positive KT recipients represent a highly-selected group within the broader HIV-positive population with advanced kidney disease. There is evidence that HIV-positive KT patients face excess challenges in achieving access to KT.11–13 For example, in a study of 319 HIV-positive patients evaluated at a high-volume transplant center in New York City from 2000 to 2007, only 20% were listed for KT compared to 73% of HIV-negative patients. Possible reasons for the lower rate of listing included CD4 counts below the required minimal threshold (< 200 cells/mm3), substance abuse, and failure to complete the entire evaluation process.12 Another study from our center, a Philadelphia-based program, described similar challenges for HIV-positive patients who were evaluated for KT.13 Once waitlist status is achieved, HIV-positive patients experience a longer time to their first organ offer and are less likely to undergo transplantation than HIV-negative patients.11,14

To provide a remedy for some of these disparities, the HIV Positive Organ Equity (HOPE) Act expanded the kidney donor pool for HIV-positive patients by allowing them to receive KT from HIV-positive donors at federally-designated transplant centers.15–17 But despite this new source of available organs, there still might be barriers that preclude HIV-positive patients from achieving the earliest milestone on the journey to transplantation: an appointment for initial KT evaluation. Thus, we sought to describe the characteristics of HIV-positive patients at our center who were KT evaluation-eligible by either eGFR criteria or dialysis-dependent status, as well as their rate of scheduled transplantation evaluation appointment. We aimed to see if there were significant differences in the characteristics between those who received a scheduled appointment for KT evaluation and those who didn’t. An improved understanding of the broader HIV population with advanced kidney disease might identify targets to reduce barriers to transplantation in the earliest stages of the process.

METHODS

Study Design and Description of Patient Cohort

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at of HIV-positive patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) who received care at the largest comprehensive primary care clinic for HIV-positive patients in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Patients were included in the study if they were HIV-positive and had evidence of KT evaluation eligibility on review of electronic medical records (EMR) from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2015. We defined eligibility for KT evaluation by the first-occurrence of either 1) documentation of dialysis-dependence within the EMR or 2) eGFR of ≤ 20 ml/min/1.73 m2 on at least two consecutive occasions, ≥ 3 months apart, so as to avoid misclassification of acute kidney injury with CKD. Evidence of dialysis-dependence was indicated by ICD 9 or 10 code for dialysis or other documentation within the EMR. The dialysis initiation date was verified by the presence of a CMS 2728 form within the record. Patients were excluded if they were < 18 years-old. The study protocol was approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board.

Covariates

We used ICD 9 and 10 codes to identify the presence of the following comorbid conditions (see appendix for a corresponding codes): schizophrenia, depression, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, cryptococcus, toxoplasmosis, Kaposi sarcoma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary hypertension, hypertension, heart failure, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, coronary artery disease, dementia, liver cirrhosis, stroke, alcohol dependence, opioid dependence, cannabis disorder, tobacco dependence, cocaine abuse, psychoactive drugs not otherwise specified. History of malignancy was ascertained from the problem list in the EMR. All conditions were adjudicated by chart review. Lab values (CD4 count, HIV viral load, hepatitis C RNA, hepatitis B surface antigen) and antiretroviral therapy (ART) prescription were from within 12 months of becoming KT evaluation-eligible. HIV viral resistance profiles were obtained from the timepoint closest to either the attainment of the qualifying eGFR for transplant evaluation or the start of dialysis-dependence (whichever came first). The etiology of kidney disease was determined by review of kidney biopsy data (if available) or documentation in the EMR.

Outcome

The primary outcome was scheduling of a KT evaluation appointment. The outcome was ascertained by reviewing the EMR for documentation of a KT evaluation appointment at Drexel University/Hahnemann University Hospital. Patients were followed for ascertainment of the outcome through December 31, 2017. Among those with scheduled appointment, we also assessed whether the initial appointment was attended. We did not have access to appointment information at transplant centers external to our own.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges and categorical variables with proportions. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess differences between continuous variables and the Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was used to designate statistical significance. We compared patients who had evidence of pre-dialysis KT-evaluation eligibility to those who were dialysis-dependent given that there might be important differences between the groups.

RESULTS

Kidney Transplant Evaluation Eligibility and Appointment Rate

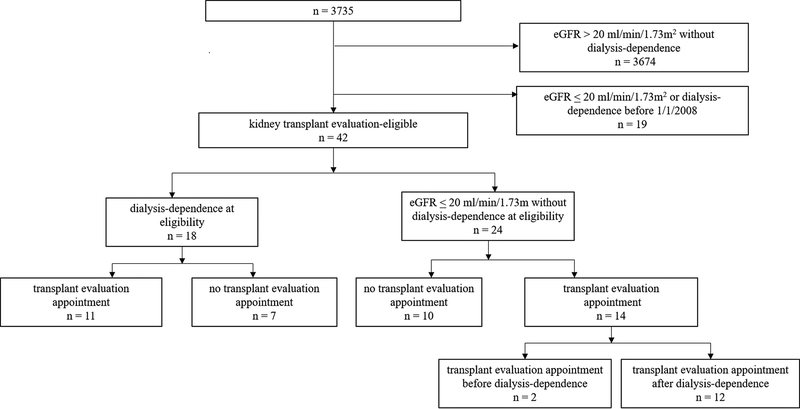

Among 3,735 patients who received care at the clinic during the study period, 61 patients (1.6%) were eligible for KT evaluation by eGFR or dialysis criteria. Nineteen of these patients were excluded from the analysis because they met eligibility criteria prior to January 1, 2008. Thus, the final analytical cohort consisted of 42 KT evaluation-eligible patients of which 57% (n = 24) qualified for evaluation prior to dialysis-dependence and 43% (n = 18) qualified at the time of dialysis-dependence. Among KT evaluation-eligible patients, 60% (n = 25) had a scheduled appointment for evaluation with only 8% (n = 2) occurring before dialysis-dependence (Figure 1). The median eGFR among those who qualified for transplant evaluation prior to dialysis-dependence was 8 ml/min/1.73 m2 (IQR 6–12 ml/min/1.73 m2). The median time from meeting eligibility criteria to receipt of an evaluation appointment was 14.8 months (IQR 9.8–25.7) with 44% within 12 months of documented initial eligibility. Of those who received an evaluation appointment (n = 25), 80% (n = 20) attended it, while 8% (n = 2) attended a subsequently-scheduled appointment and 12% (n = 3) had no evidence of attending any appointment. There was no statistically significant difference in the median time to an appointment for patients with and without ART prescription (16.2 months vs. 17.5 months; p-value 0.8), nor in those with undetectable (HIV viral load < 200 copies) vs. detectable HIV viral loads at the time of becoming eligible for evaluation (17.8 months vs. 10.5 months, respectively; p-value 0.9).

Figure 1.

Assembly of the Study Cohort. Of 42 patients who were kidney transplant evaluation‐eligible by study inclusion criteria, 18 had evidence of eligibility at dialysis dependence and of these, 11 had documented evaluation appointments. Twenty‐four patients at evidence of eligibility before dialysis dependence and of these, 14 had documented evaluation appointments with two occurring before dialysis dependence (that is, preemptive).

Characteristics of Kidney Transplant Evaluation-Eligible Patients

Characteristics of patients eligible for a KT evaluation appointment are shown in Table 1. Eleven variables had some amount of missing data, all of which were < 10% with the exception of hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C RNA, and the year of HIV diagnosis (Table 1). The median age was 47 years; 74% were men; 95%, black; and none, Hispanic. The median body mass index (BMI) was 26.5 kg/m2 (IQR 24.6–29.9), and the median year of HIV diagnosis was 1995 (IQR 1989–2000). A diagnosis of psychiatric disease was documented in 62% (n = 26) of patients with depression accounting for 40% (n = 17); anxiety, 22% (n = 10); and schizophrenia, 14% (n = 6). A history of drug abuse was noted in 45% (n = 19) of patients. Only 8% (n = 3) were employed.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of KT-Eligibility at the Time of Eligibility

| Variable | All Patients (n = 42) | No Transplant Evaluation Appointment (n = 17) | Transplant Evaluation Appointment (n =25) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 47.4 (43.1–53.5) | 47.7 (43.5–52.8) | 45.7 (43.1–53.5–52.0) | 0.81 |

| Male | 74% (n = 31) | 71% (n = 12) | 76% (n=19) | 0.70 |

| Race† | 0.80 | |||

| Black | 95% (n = 39) | 94% (n = 16) | 92% (n = 23) | |

| White | 5% (n = 2) | 6% (n = 1) | 4% (n = 1) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity† | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1.0 |

| Body mass index | 26.5 (24.6–29.9) | 26.3 (25.6–29.0) | 25.5 (23.6–30.0) | 0.95 |

| Evaluation eligible before dialysis-dependence | 57% (n = 24) | 59% (n = 10) | 56% (n =14) | 0.86 |

| Year of initial evaluation eligibility | 0.12 | |||

| 2008–2009 | 36% (n = 15) | 24% (n = 4) | 44% (n = 11) | |

| 2010–2011 | 21% (n = 9) | 12% (n = 2) | 28% (n = 7) | |

| 2012–2013 | 21% (n = 9) | 29% (n = 5) | 16% (n = 4) | |

| 2014–2015 | 21% (n = 9) | 35% (n = 6) | 12% (n = 3) | |

| Psychiatric disease | 62% (n = 26) | 76% (n = 13) | 52% (n = 13) | 0.11 |

| Schizophrenia | 14% (n = 6) | 29% (n = 5) | 4% (n = 1) | 0.02 |

| Bipolar disorder | 5% (n = 2) | 12% (n = 2) | 0% (n = 0) | 0.07 |

| Depression | 40% (n = 17) | 47% (n =8) | 36% (n = 9) | 0.47 |

| Anxiety | 22% (n = 10) | 18% (n = 3) | 28% (n = 7) | 0.44 |

| History of opportunistic infection | 17% (n = 7) | 24% (n = 4) | 12% (n = 3) | 0.33 |

| Pulmonary disease | 10% (n = 4) | 6% (n = 1) | 12% (n = 3) | 0.51 |

| Hypertension | 90 % (n = 38) | 88% (n = 15) | 92% (n = 23) | 0.68 |

| Heart failure | 14% (n = 6) | 6% (n = 1) | 20% (n = 5) | 0.20 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1.0 |

| Coronary artery disease | 24% (n = 10) | 24% (n = 4) | 24% (n = 6) | 0.97 |

| Malignancy | 10% (n = 6) | 12% (n = 2) | 4% (n = 1) | 0.34 |

| Dementia | 5% (n = 2) | 6% (n = 1) | 4% (n = 1) | 0.78 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40% (n = 17) | 29% (n = 5) | 48% (n = 12) | 0.23 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 14% (n = 6) | 6% (n = 1) | 20% (n = 5) | 0.20 |

| Stroke | 21% (n = 9) | 24% (n = 4) | 20% (n = 5) | 0.78 |

| History of drug disorder | 45% (n = 19) | 41% (n = 7) | 48% (n = 12) | 0.66 |

| History of opioid dependence | 7% (n = 3) | 0% (n = 0) | 12% (n = 3) | 0.14 |

| History of cocaine abuse | 19% (n = 8) | 29% (n = 5) | 12% (n = 3) | 0.16 |

| History of cannabis disorder | 17% (n = 7) | 6% (n = 1) | 24% (n = 6) | 0.12 |

| History of abuse of psychoactive drugs, not otherwise specified | 19% (n = 8) | 18% (n = 3) | 20% (n = 5) | 0.85 |

| History of alcohol abuse | 17% (n = 7) | 24% (n = 4) | 12% (n = 3) | 0.33 |

| History of tobacco use | 74% (n = 31) | 71% (n = 12) | 76% (n = 19) | 0.70 |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3)† | 328 (175–461) | 318 (89–368.5) | 358 (201–509) | 0.17 |

| CD4 count (> 200 cells/mm3) | 71% (n = 30) | 65% (n = 11) | 76% (n = 19) | 0.43 |

| HIV viral load (copies) | 313 (20–49,110) | 629 (20–49,110) | 208 (20.0–26,050) | 0.77 |

| Detectable HIV viral load (>200 copies) | 54% (n = 22) | 53% (n = 9) | 52% (n = 13) | 0.79 |

| Detectable Hepatitis C RNA† | 48% (n = 14) | 24% (n = 4) | 40% (n = 10) | 0.78 |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen† | 6% (n = 2) | 0% (n = 0) | 8% (n = 2) | 0.34 |

| Etiology of kidney disease | 0.02 | |||

| HIV nephropathy | 19% (n = 8) | 12% (n = 2) | 24% (n = 6) | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 12% (n = 5) | 6% (n = 1) | 16% (n = 4) | |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 24% (n = 10) | 12% (n = 2) | 32% (n = 8) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urinary tract | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Solitary kidney | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Multi-factorial | 19% (n = 8) | 17% (n = 3) | 20% (n= 5) | |

| Unknown | 25% (n = 11) | 53% (n =9) | 8% (n = 2) | |

| Marriage status† | 0.54 | |||

| Married | 24% (n = 9) | 24% (n =4) | 20% (n = 5) | |

| Single | 68% (n = 26) | 65% (n = 11) | 60% (n =15) | |

| Divorced | 5% (n = 2) | 0% | 8% (n = 2) | |

| Widowed | 3% (n = 1) | 0% | 4% (n = 1) | |

| Living in an institution | 12% (n = 5) | 13% (n = 3) | 5% (n = 2) | 0.37 |

| Employed† | 8% (n = 3) | 0% (n =0) | 12% (n = 3) | 0.16 |

| English as a first language† | 97% (n = 40) | 92% (n = 22) | 97% (n = 36) | 0.73 |

| Insurance† | 0.10 | |||

| Medicare | 55% (n = 22) | 35% (n = 6) | 64% (n = 16) | |

| Medicaid | 40% (n = 16) | 41% (n = 7) | 36% (n = 9) | |

| Private | 5% (n = 2) | 12% (n = 2) | 0% | |

| Year of HIV Diagnosis† | 1995 (1989–2000) | 1993 (1989–1997) | 1996 (1990–2004) | 0.40 |

| Year of initiation of ART | 0.15 | |||

| 1986–2000 | 17% (n = 7) | 24% (n = 4) | 12% (n = 3) | |

| 2001–2005 | 4% (n =2) | 6% (n = 1) | 4% (n = 1) | |

| 2006–2010 | 31% (n =13) | 12% (n = 2) | 44% (n = 11) | |

| 2011–2015 | 19% (n =8) | 12% (n = 2) | 24% (n = 6) | |

| Unknown | 29% (n =12) | 47% (n = 8) | 16% (n = 4) | |

| ART at the time of qualifying for transplant evaluation † | 63% (n = 25) | 76% (n = 13) | 48% (n =12) | 0.04 |

Continuous Variables Expressed as Medians and IQR

The following are the variables with missing data (percentage missingness): race (2%), ethnicity (2%), CD4 count (2%); hepatitis B surface antigen (21%), detectable hepatitis C RNA (31%); marital status (9%); employment status (5%); insurance (5%); ART at time of transplant qualification (5%); English as first-language(2%); year of HIV diagnosis (35%).

At the time of initial KT evaluation eligibility, the median CD4 count in the KT-eligible population was 328 cells/mm3 (IQR 175–461). Fifty-four percent of patients had viral loads of greater than 200 copies. Sixty-three percent were on ART at the time of initial eligibility, and of these, 40% had a viral load > 200 copies. Twenty-percent of regimens consisted of a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRT); 76%%, protease inhibitor (PI); 84%, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI); 36%, an integrase inhibitor; and 12%, fusion inhibitor (Table 2). Of those patients who had a resistance profile on record (n = 21; 50%), 52% exhibited resistance (Table 3). The most common type of resistance was to NRTIs (n = 10). The most prevalent HIV mutations documented were M184V, K103N, thiamine analog mutation (TAM)(Supplemental Table 2). The median year of HIV diagnosis in patients with resistance was 1995 (IQR 1989–2000).

Table 2:

Anti-Retroviral Therapy of Kidney Transplant Evaluation-Eligible Patients

| Category of ART | Patients on ART at the time of KT evaluation-eligibility (n = 25) | No Transplant Evaluation Appointment (n = 13) | Transplant Evaluation Appointment (n =12) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease inhibitor | 76% (n = 19) | 77% (n = 10) | 75% (n = 9) | 0.91 |

| NRTI | 84% (n = 21) | 92% (n = 12) | 75% (n = 9) | 0.24 |

| NNRTI | 20% (n = 5) | 15% (n = 2) | 25% (n= 3) | 0.55 |

| Integrase inhibitor | 36% (n = 9) | 38% (n = 5) | 33% (n = 4) | 0.79 |

| Fusion inhibitor | 12% (n = 3) | 8% (n = 1) | 17% (n =2) | 0.49 |

| Fixed dose combination pill | 32% (n = 8) | 31% (n = 4) | 33% (n = 4) | 0.89 |

| Single tab ART regimen | 0% | 0% | 0% | - |

| Resistance profile on record | 52% (n = 13) | 46% (n = 6) | 58% (n =7) | 0.54 |

Table 3:

Anti-Retroviral Therapy Resistance in Kidney Transplant Evaluation-Eligible Patients

| Patients with Resistance Profiles on Record (n = 21) | No Transplant Evaluation Appointment (n = 9) | Transplant Evaluation Appointment (n =9) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence of resistance | 52% (n = 11) | 78% (n = 7) | 33% (n = 4) | 0.04 |

| Type of Resistance | ||||

| Protease inhibitor | 14% (n =3) | 33% (n = 3) | 0% | 0.03 |

| NRTI | 48% (n =10) | 78% (n = 7) | 25% (n = 3) | 0.02 |

| NNRTI | 29% (n = 6) | 44% (n = 4) | 17% (n = 2) | 0.16 |

| Integrase Inhibitor | 5% (n = 1) | 11% (n =1) | 0% | 0.24 |

Patients who had documented evidence of KT evaluation-eligibility before dialysis-dependence had a higher prevalence of diabetes than those who did not (58% vs. 17%; p < 0.01), a higher prevalence of hypertension (100% vs. 84%, p = 0.02), and a higher median BMI (27.7 vs. 25.6., p = 0.05). Otherwise, those with pre-dialysis eligibility vs. those without it were not significantly different (Supplemental Table 1).

Differences Between Patients with and without an Appointment for Transplant Evaluation

See Table 1 for demographic, comorbid, and social characteristics of patients with (n = 25) and without (n = 17) documented KT evaluation appointments. There were statistically significant differences between the two groups in prevalence of schizophrenia (patients with an appointment, 4% vs. without, 29%; p = 0.02), prescription of ART at the time of KT evaluation-eligibility (patients with an appointment, 48% vs. without, 76%; p = 0.04), evidence of viral resistance (33% with appointments, 78% without appointments; p = 0.04), and in etiology for kidney disease (p = 0.02). For those without KT evaluation appointment, the etiology of kidney disease was not known in 53% of the patients vs. 8% of those with appointments. Patients without KT evaluation appointments trended towards higher prevalence of any psychiatric disease (patients with appointment, 52%, patients without, 76%), higher unemployment (patients with an appointment, 88% vs. without, 100%), higher prevalence of alcohol abuse history (patients with an appointment, 12% vs without, 24%), cocaine abuse history (patients with an appointment, 12% vs. without, 29%). There were similar rates of detectable viral loads and CD4 counts in both groups.

DISCUSSION

Our study found that among HIV-positive KT evaluation-eligible patients, there was a high co-morbidity burden, including a particularly high prevalence of psychiatric disease and substance abuse. However, for those without evidence of an appointment for KT evaluation, there was significantly more schizophrenia and viral resistance as well as a non-significant trend towards more overall psychiatric illness, substance abuse, and unemployment. This suggests that psychosocial issues are a significant barrier to receipt of KT evaluation in this population. Higher rates of viral resistance in patients without appointments could potentially be a surrogate marker for longer-standing, poorer controlled HIV, possibly from non-adherence. This might also explain the higher prevalence in ART prescription among those without appointments, considering that during the study period, ART-guidelines recommended initiation for those with CD4 counts < 350 cells/mm3.18–20 It wasn’t until 2015 that expert guidelines advised universal ART, irrespective of CD4 count.20 Therefore, in this study, ART prescription could mark a more severe HIV phenotype, either due to viral strain, duration of infection, or non-adherence. The observation that significantly more patients without KT evaluation appointments lacked documentation of kidney disease etiology suggests that perhaps they commenced nephrology care late in their CKD course, had rapidly-progressive CKD phenotypes that precluded early diagnosis, or were hindered from early diagnosis by non-adherence.

Despite the high burden of psychiatric disease, substance abuse history, and other comorbid conditions in our study cohort, 60% received an appointment for KT evaluation. Comparison data from other ESKD populations are limited due to significant practical barriers to assessing both appointment rates and/or referral rates due to lack of a centralized national data source. In analyses of dialysis-dependent patients in the state of Georgia, which captured referrals from all accredited transplant centers in the state and linked them with patient-level data in the Unites States Renal Data System, the median within-facility transplant referral rate within 1-year of dialysis-dependence was approximately 25%. 21,22 The relatively higher overall appointment rate in our HIV-positive population compared to estimated rates in Georgia’s general ESKD population could be explained by physician practice patterns that are unique to our center, Drexel University/Hahnemann, which had more than a decade of experience with KT in HIV-positive patients.23 Of note, our center evaluated HIV-positive patients with CD4 counts < 200 cells/mm3 and detectable viral loads, or who were not yet on ART. Although these patients were not eligible for active waitlist status, the evaluation afforded an opportunity for patient education and ART modification that could improve the likelihood of a patients’ waitlist candidacy in the future.

Although 57% of patients had evidence of eligibility for KT evaluation before dialysis-dependence, only 8% of them received an appointment for pre-emptive evaluation. This statistic is similar to the pre-emptive referral rate and pre-emptive listing rate reported by Sawinski, et. al, and Locke, et. al, respectively, in other HIV-positive cohorts, but is lower than pre-emptive referral and listing rates in the general ESKD population.11,12,21,22 In our cohort, a statistically significant proportion of patients with evidence of KT-evaluation eligibility prior to dialysis-dependence were diabetic, hypertensive, and had a higher median BMI compared to those with evidence of eligibility only after dialysis-dependence. Hypothetical explanations for this include that the rate of CKD progression in diabetics was slower than in non-diabetics, or that diabetics underwent more frequent surveillance by health providers and might have had kidney disease screening sooner in their CKD course than non-diabetics. Despite the possibility that diabetics had closer clinical surveillance than non-diabetics, the pre-emptive appointment rate was still low. Additional investigation is needed to better understand barriers to pre-emptive access to KT evaluation in HIV-positive patients.

HIV resistance rates and mutation frequencies are critical to controlling HIV disease in individual patients and populations. With the inception of HIV-positive to HIV-positive organ transplantation, knowledge of resistance patterns is important to estimating the chance that transplantation will lead to acquisition of a new viral strain in the recipient.24 Although HIV resistance profiles were only recorded in 50% of patients (possibly attributable to failure to transfer profiles from paper copies to scanned copies in the EMR), among these patients, resistance was present in 52%. The most common resistance mutations in our cohort were to NRTIs, followed by NNRTIs. This overall resistance rate is higher than the 29% global resistance rate quoted by the World Health Organization in its 2017 report.25 Only one patient in the cohort had resistance to integrase inhibitors. While this is not surprising given this class’s relatively high genetic barrier to resistance, it is an important observation in kidney transplant candidates given that integrase inhibitors are preferred agents post-transplant because they do not have interactions with conventional immunosuppression.26,27

At the time of transplant evaluation eligibility, the majority our cohort, regardless of appointment status and dialysis-dependence, had detectable HIV viral loads. As previously noted, this could have been affected by HIV guideline changes over the years as ART initiation was dependent on CD4 counts.18,20 However, this does not explain why 40% of patients in our study with ART prescriptions still had poor viral control, particularly considering that in the current era of universal ART prescription, approximately 80% of our overall HIV primary care clinic has undetectable viral loads. One possibility is higher non-adherence rates due to less tolerable ART regimens or to excessive co-morbidity and pill burden, which might disproportionally affect the ESKD population.28 Another is that pharmacokinetic profiles of ART in patients with varying dialysis schedules and native renal clearances might be perturbed in adverse ways. Future investigation is necessary to explore this further.

Our study has limitations. First, its small, single-center design may lessen it generalizability to other populations. The overall transplant evaluation appointment rate observed (60%) was higher than referral rates published for general ESKD populations, but our cohort lacked an HIV-negative control group for comparison. We were unable to verify whether appointment referrals were generated from the HIV practice itself vs. patients’ own initiation vs. from patients’ dialysis units. The small sample size might have precluded us from identifying other significant differences between patients with and without appointments. Also, for those in our cohort who had evidence of KT-evaluation eligibility only after dialysis-dependence, we were unable to ascertain the reason for this. Some possibilities are receipt of pre-dialysis appointments in another health system vs. rapid progression to dialysis-dependence that precluded pre-dialysis eligibility vs. inability to access pre-dialysis care. We did not capture data on loss to follow-up or death, which limited our ability to determine if these competing events affected KT-evaluation appointment rates. Finally, our retrospective design and focus on transplant appointment documentation may increase the potential for information bias in the ascertainment of access to KT evaluation. That is, KT evaluation referrals might not materialize into actual appointments for all patients. However, as the HIV primary care practice and our transplant center were contained within the same health system, most patients were likely to be referred within the system, and if they were referred outside of the system, this would underestimate the study populations’ access to KT evaluation, not overestimate it. In addition, there have been updates in ART prescription guidelines and additions to ART options since the study period. Despite these limitations, this study offers granular data about HIV-positive patients with advanced CKD in the context of KT evaluation access, including extensive co-morbidities, psychosocial attributes, and viral mutation patterns, which are often more challenging to obtain from larger administrative datasets.

In conclusion, HIV-positive KT evaluation-eligible patients at our single center primary care clinic had a high co-morbidity burden, including psychiatric disease and history of substance abuse. Despite this, the majority of patients had documented evidence of KT-evaluation appointments. However, a minority of patients received KT-evaluation appointments prior to dialysis-dependence. Patients without evidence of KT-evaluation appointments were disproportionally afflicted with schizophrenia and were more likely to have viral resistance than patients with appointments. These findings underscore important characteristics of the overall HIV-positive population with advanced kidney disease. They also suggest that more resources are needed to address the psychosocial challenges that prevent some HIV-positive patients from initiating the transplant evaluation process. Like others, this cohort study suggests that HIV-positive patients might have a lower probability of initiating the transplant evaluation process before dialysis-dependence than HIV-negative patients.11,12 More work is needed to understand the reason for this disparity. Further, future studies should aim at tracking the origin of KT-evaluation appointment referrals. This will allow for identification of the most successful referral pathways and inform efforts to reform underutilized pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

MNH is supported by a grant from the NIH - K23DK105207.

Abbreviations

- KT

kidney transplant

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Sawinski D, Forde KA, Locke JE, et al. Race but not Hepatitis C co-infection affects survival of HIV(+) individuals on dialysis in contemporary practice. Kidney international. 2018;93(3):706–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham AG, Althoff KN, Jing Y, et al. End-stage renal disease among HIV-infected adults in North America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;60(6):941–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bickel M, Marben W, Betz C, et al. End-stage renal disease and dialysis in HIV-positive patients: observations from a long-term cohort study with a follow-up of 22 years. HIV medicine. 2013;14(3):127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez RA, Mendelson M, O’Hare AM, Hsu LC, Schoenfeld P. Determinants of survival among HIV-infected chronic dialysis patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2003;14(5):1307–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucas GM, Lau B, Atta MG, Fine DM, Keruly J, Moore RD. Chronic kidney disease incidence, and progression to end-stage renal disease, in HIV-infected individuals: a tale of two races. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008;197(11):1548–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggers PW, Kimmel PL. Is there an epidemic of HIV Infection in the US ESRD program? Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2004;15(9):2477–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahuja TS, Grady J, Khan S. Changing trends in the survival of dialysis patients with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2002;13(7):1889–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trullas JC, Cofan F, Barril G, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in HIV-1-infected patients on dialysis in the cART era: a GESIDA/SEN cohort study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011;57(4):276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stock PG, Barin B, Murphy B, et al. Outcomes of kidney transplantation in HIV-infected recipients. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(21):2004–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Locke JE, Mehta S, Reed RD, et al. A National Study of Outcomes among HIV-Infected Kidney Transplant Recipients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015;26(9):2222–2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Locke JE, Mehta S, Sawinski D, et al. Access to Kidney Transplantation among HIV-Infected Waitlist Candidates. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2017;12(3):467–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawinski D, Wyatt CM, Casagrande L, et al. Factors associated with failure to list HIV-positive kidney transplant candidates. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9(6):1467–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee DH, Boyle SM, Malat GE, et al. Barriers to listing for HIV-infected patients being evaluated for kidney transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen JB, Locke JE, Shelton B, et al. Disparity in access to kidney allograft offers among transplant candidates with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Transplant. 2019;33(2):e13466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Final Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Organ Policy Equity (HOPE) Act Safeguards and Research Criteria for Transplantation of Organs Infected with HIV. Vol 802015:73785–73796. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyarsky BJ, Bowring MG, Shaffer AA, Segev DL, Durand CM. The future of HIV Organ Policy Equity Act is now: the state of HIV+ to HIV+ kidney transplantation in the United States. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2019;24(4):434–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilk AR, Hunter RA, McBride MA, Klassen DK. National landscape of HIV+ to HIV+ kidney and liver transplantation in the United States. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2019;19(9):2594–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rathbun RC, Lockhart SM, Stephens JR. Current HIV treatment guidelines--an overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(9):1045–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta SK, Eustace JA, Winston JA, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic kidney disease in HIV-infected patients: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005;40(11):1559–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibert CL. Treatment Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents: An Update. Fed Pract. 2016;33(Suppl 3):31S–36S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patzer RE, Plantinga LC, Paul S, et al. Variation in Dialysis Facility Referral for Kidney Transplantation Among Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease in Georgia. Jama. 2015;314(6):582–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plantinga LC, Pastan SO, Wilk AS, et al. Referral for Kidney Transplantation and Indicators of Quality of Dialysis Care: A Cross-sectional Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2017;69(2):257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malat GE, Boyle SM, Jindal RM, et al. Kidney Transplantation in HIV-Positive Patients: A Single-Center, 16-Year Experience. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2019;73(1):112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyarsky BJ, Durand CM, Palella FJ Jr., Segev DL. Challenges and Clinical Decision-Making in HIV-to-HIV Transplantation: Insights From the HIV Literature. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2015;15(8):2023–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beyrer C, Pozniak A. HIV Drug Resistance - An Emerging Threat to Epidemic Control. The New England journal of medicine. 2017;377(17):1605–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawinski D, Shelton BA, Mehta S, et al. Impact of Protease Inhibitor-Based Anti-Retroviral Therapy on Outcomes for HIV+ Kidney Transplant Recipients. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2017;17(12):3114–3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumberg EA, Rogers CC, American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of P. Solid organ transplantation in the HIV-infected patient: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019:e13499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghimire S, Castelino RL, Lioufas NM, Peterson GM, Zaidi ST. Nonadherence to Medication Therapy in Haemodialysis Patients: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.