Abstract

Background

Medical publications about anosmia with COVID-19 are scarce. We aimed to describe the prevalence and features of anosmia in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

We retrospectively included COVID-19 patients with anosmia between March 1st and March 17th, 2020. We used SARS-CoV-2 real time PCR in respiratory samples to confirm the cases.

Results

Fifty-four of 114 patients (47%) with confirmed COVID-19 reported anosmia. Mean age of the 54 patients was 47 (± 16) years; 67% were females and 37% were hospitalised. The median Charlson comorbidity index was 0.70 (± 1.6 [0–7]). Forty-six patients (85%) had dysgeusia and 28% presented with pneumonia. Anosmia began 4.4 (± 1.9 [1–8]) days after infection onset. The mean duration of anosmia was 8.9 (± 6.3 [1–21]) days and 98% of patients recovered within 28 days.

Conclusions

Anosmia was present in half of our European COVID-19 patients and was often associated with dysgeusia.

Keywords: COVID-19, Anosmia, Dysgeusia

1. Introduction

Clinical description from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China reveals that most patients (81%) present with influenza-like illness (ILI) or mild pneumonia, and 19% of cases experience severe or critical pneumonia [1]. Fever, cough, fatigue, and myalgia are usually the main symptoms. The expression of COVID-19 ILI seems non-specific; no specific symptom can lead to suspecting a case without any notion of exposure [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. A major French cluster of COVID-19 began on March 1st, 2020 in the city of Mulhouse, France (less than 30 miles from our hospital). After clinical examination of the first patients, we noticed that many cases reported anosmia. The description of anosmia and other ENT symptoms is scarce with COVID-19. For instance, a recent review on COVID-19 by ENT specialists on March 26 emphasised that ENT symptoms were uncommon with COVID-19 as nasal congestion and rhinorrhea were observed in less than 5% of cases. However, they noticed that there were few reports of anosmia and dysgeusia with no real description of symptoms [8]. Recently, in April, descriptions of cases of anosmia in a multicentric cohort have been associated with COVID-19 [9], [10], [11]. We aimed to describe the prevalence and features of anosmia in COVID-19 patients.

2. Method

We conducted a retrospective observational study in the NFC (Nord Franche-Comté) hospital. Between March 1st and March 17th, 2020, we enrolled all adult patients (≥ 18 years) with confirmed COVID-19 who were examined at the infectious disease consultation or hospitalised in the hospital and who reported anosmia. Pregnant women, children (< 18 years), and patients with dementia (who cannot report functional symptoms) were excluded. We stopped the study follow-up on March 24th, 2020.

Diagnosis was confirmed by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) on respiratory samples, mainly nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum, bronchial aspirates, or bronchoalveolar lavage fluids. Viral RNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin® RNA Virus kit (Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and amplified by RT-PCR protocols developed by Charité (E gene) [12] and the Institut Pasteur (RdRp gene) [13] on LightCycler 480 (Roche). Quantified positive controls were kindly provided by the French National Reference Centre for Respiratory Viruses, Institut Pasteur, Paris.

Our national guidelines recommended home follow-up for non-hospitalised patients [14]. Non-hospitalised and discharged patients were called seven days (± 7 days) after the first symptoms and every week until recovery to monitor clinical outcome. Data required for the study was collected from the medical files of patients: age, sex, comorbidities, features of anosmia (date of apparition since symptom onset, duration of anosmia), other symptoms, physical signs, and outcome. Usual descriptive statistics were used. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers, percentages, or mean. Continuous variables were expressed as mean with standard deviation (SD).

We aimed to describe the prevalence and characteristics of anosmia in patients with confirmed COVID-19.

3. Results

Fifty-four of 114 patients (47%) with confirmed COVID-19 reported anosmia and were included in this study. Among these 54 patients, the mean age was 47 (± 16) years and 36 (67%) were females. The median Charlson comorbidity index was 0.70 (± 1.6 [0–7]). The most frequent comorbidities were asthma (13%, n = 7), arterial hypertension (13%, n = 7), and cardiovascular disease (11%, n = 6). Other comorbidities were less frequent (Table 1 ) and no patient had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Table 1.

Comorbidities, symptoms, and outcome of the 54 patients with anosmia.

Comorbidités, symptômes et devenir des 54 patients anosmiques.

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Medical history | |

| Age (Y): mean (SD) | 47 (± 16) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 36 (67%) |

| Male | 18 (33%) |

| Current smoking | 6 (11%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Arterial hypertension | 7 (13%) |

| Cardiovascular diseasea | 6 (11%) |

| Diabetes | 2 (4%) |

| Asthma | 7 (13%) |

| COPDb | 0 (6%) |

| Malignancy | 2 (4%) |

| Immunosupressionc | 1 (4%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index: mean (SD) | 0.70 (± 1.6, [0–7]) |

| ENT symptoms | |

| Rhinorrhea | 31 (57%) |

| Nasal obstruction | 16 (30%) |

| Epistaxis | 6 (11%) |

| Dysgeusia | 46 (85%) |

| Tinnitus | 6 (11%) |

| Hearing loss | 4 (7%) |

| Other symptoms | |

| Fever measured > 38 °C | 40 (74%) |

| Feeling of fever | 12 (22%) |

| Highest temperature (T°C): mean (SD) | 38.6 (± 0.8) |

| Fatigue | 50 (93%) |

| Myalgia | 40 (74%) |

| Arthralgia | 39 (72%) |

| Sore throat | 23 (43%) |

| Headaches | 44 (82%) |

| Conjunctival hyperemia | 2 (4%) |

| Tearing | 4 (7%) |

| Dry eyes | 2 (4%) |

| Blurred vision | 4 (7%) |

| Sneezing | 18 (33%) |

| Cough | 47 (87%) |

| Sputum production | 12 (22%) |

| Hemoptysis | 3 (6%) |

| Dyspnea | 21 (39%) |

| Respiratory rate > 22/min | 10 (19%) |

| Sat O2 at admission (%) | 94.6 (± 4.6) |

| Auscultation with crackling sounds | 15 (28%) |

| Nausea | 19 (35%) |

| Vomiting | 3 (6%) |

| Diarrhea | 28 (52%) |

| Abdominal pain | 15 (28%) |

| Outcome | |

| Hospitalisation | 20 (37%) |

| Hospitalisation in the intensive care unit | 5 (9%) |

| Oxygen therapy | 11 (20%) |

| Death | 2 (4%) |

Defined by: cardiac failure, cardiac arrhythmia, coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral arterial obstructive disease, and thromboembolic disease.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Defined by: transplantation, cirrhosis, long-term steroid therapy, and immunomodulator treatments.

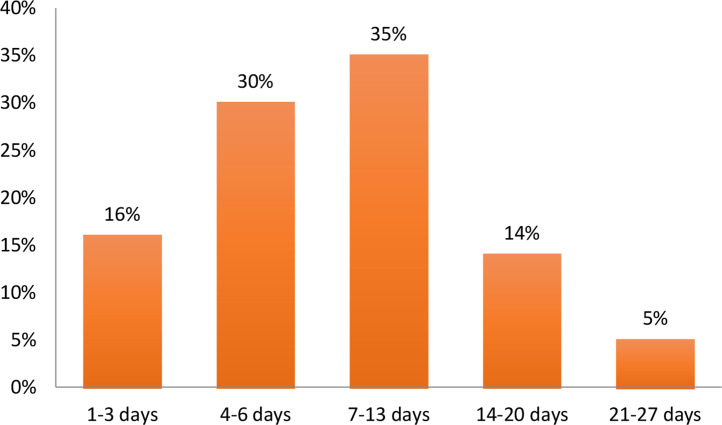

Among the 54 patients, the mean duration of anosmia was 8.9 (± 6.3 [1–21]) days. Duration was ≥ 7 days for 55% (24/44) and ≥ 14 days for 20% (9/44) (Fig. 1 ); one patient (1/44) had not recovered at the end of the follow-up (after 28 days). Anosmia was never the first or second symptom to develop, but it was the third symptom in 38% (22/52) of cases. Anosmia developed 4.4 (± 1.9 [1–8]) days after infection onset.

Fig. 1.

Recovery time for patients with anosmia (n = 43 patients, 10 patients did not remember duration until recovery and one patient did not recover after 28 days).

Durée de l'anosmie (n=43, 10 patients ne se rappelaient pas de la durée et 1 patient était toujours anosmique à J28).

As for the other ENT symptoms, anosmia was associated with dysgeusia in 85% of cases (n = 46). Thirty-one patients had rhinorrhea (57%) and only 16 patients (30%) had nasal obstruction. Epistaxis, tinnitus, and hearing loss were uncommon (< 15%).

As for other symptoms, seven symptoms were present in more than half of patients: fatigue (93%, n = 50), cough (87%, n = 47), headache (82%, n = 44), fever (74%, n = 40), myalgia (74%, n = 40), arthralgia (72%, n = 39), and diarrhea (52%, n = 28). Other symptoms were less present (Table 1).

Fifteen (28%) patients received a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia with COVID-19. Their oxygen saturation was at 94.6% [± 4.6] at admission. More than a third of our patients (37%, n = 20) were hospitalised, including five patients (9%) in the intensive care unit (ICU). Four patients (7%) had oxygen saturation < 90% at admission, 11 patients (20%) needed oxygen therapy during hospitalisation, and two patients (4%) died.

4. Discussion

A multicentric European study published on April 6 conducted by Lechien et al. reported 357 patients with olfactory dysfunction related to COVID-19 [11]. We mostly used this publication to discuss our results, as it is the only publication with a large cohort of patients with COVID-19-related olfactory dysfunction.

The mean age of our population was 47 (± 16) years, and 67% were females. The prevalence of asthma in our study was ≥ 10% and we did not have any COPD patient, which is uncommon in patients with COVID-19. Patients with anosmia seemed to be younger with a predominance of females, they had fewer comorbidities with a lower Charlson comorbidity index (< 1), and more often presented with asthma in comparison with the population usually described with COVID-19; the same population characteristics were described by Lechien et al.

Until recently, ENT symptoms had not been reported with COVID-19, except for nasal congestion and rhinorrhea [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. However, 54 (47%) of our 114 COVID-19 patients reported anosmia. Lechien et al. reported anosmia in 86% (n = 357/417) of their patients. This higher frequency may be explained by their population profiles, which were ambulatory cases that consulted at ENT consultations (patients with a mean age of 37 [± 11.4] years without cardiovascular comorbidities) and for whom it is probably easier to relate functional symptoms than patients with oxygen therapy or critical patients. Anosmia was therefore a frequent symptom in COVID-19 patients in our French study and in this European study. However, few descriptions of ENT symptoms are available, especially in Asian studies. These differences between Asia and Europe should be discussed. We made several assumptions. First, the theoretical possibility of a mutation of SARS-CoV-2 viral genome associated with a clinical impact, but not yet described. On the other hand, it is difficult to precisely report ENT symptoms of critical patients. These symptoms may seem of less importance when considering the potential severity of the disease [15]. Finally, Lechien et al. discussed the affinity of SARS-CoV-2 for tissues and individual possible genetic features. Their main argument was that the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (as receptor of SARS-CoV-2) can be specific to an ethnic group.

Anosmia was associated with dysgeusia in 85% of cases and in more than half of cases with rhinorrhea (57%). However, 70% of our patients with anosmia did not present with nasal obstruction. This leads to suspecting another pathogenesis for anosmia than mechanical nasal obstruction. In addition, anosmia during viral rhinitis with nasal obstruction usually resolves within three days [16], while we observed a mean duration of anosmia of nine days. The concept of anosmia after viral infection is known as post-infectious/post-viral olfactory loss (POL). Different kind of viruses can induce POL, including coronaviruses such as HCoV-229E [17]. However, medical literature data indicates that the duration of POL can be long: a study of 63 patients with POL reported that after one year 80% of patients had subjective recovery [18]. In our study, only one patient did not recover at the end of the study follow-up (after a follow-up of 28 days); 80% of our patients recovered within 14 days. Compared with POL, the outcome of COVID-19-related acute anosmia most frequently seems favourable in the short term.

Our patients had the same other symptoms (other than ENT symptoms) as those reported in other studies [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. However, just like Lechien et al., we observed that diarrhea was reported in more than 50% of patients. Except for one study (occurrence of 33%), the occurrence of diarrhea is < 20% in the medical literature [19]. The frequency of diarrhea seems to be high in patients with anosmia.

One of our study limitations was the limited number of patients. However, our study is, to our knowledge, the main monocentric cohort of confirmed COVID-19 patients with anosmia in France and in the medical literature. Our results are similar to those published by the recent multicentric European study performed by Lechien et al.

5. Conclusion

COVID-19-related anosmia is a new description in the medical literature. Half of the patients with COVID-19 present with anosmia. Anosmia is associated with dysgeusia in more than 80% of cases. The outcome seems favourable in less than 28 days. This notion needs to be communicated to the medical community.

Contribution of authors

SZ and JNKO collected the epidemiological and clinical data. TK and SZ drafted the article. LT, PYR, QL, and VG reviewed the final version of the article.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Zahra Hajer for her help.

References

- 1.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [cited 2020 Mar 23; available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2762130] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalised patients with 2019 novel Coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Yang B, Li Q, Wen L, Zhang R. Clinical features of 69 cases with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis, 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 22]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/advancearticle/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa272/5807944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wu J, Liu J, Zhao X, Liu C, Wang W, Wang D, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Imported Cases of COVID-19 in Jiangsu Province: A Multicenter Descriptive Study. Clin Infect Dis, 2020 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 22]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/cid/advancearticle/doi/10.1093/cid/ciaa199/5766408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J., et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. medRxiv. 2020 [2020.02.06.20020974] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vukkadala N., Qian Z.J., Holsinger F.C., Patel Z.M., Rosenthal E. COVID-19 and the otolaryngologist – preliminary evidence-based review. Laryngoscope. 2020 doi: 10.1002/lary.28770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gane S.B., Kelly C., Hopkins C. Isolated sudden onset anosmia in COVID-19 infection. A novel syndrome? Rhinology. 2020 doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaira L.A., Salzano G., Deiana G., De Riu G. Anosmia and ageusia: common findings in COVID-19 patients. Laryngoscope. 2020 doi: 10.1002/lary.28692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lechien J.R., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., De Siati D.R., Horoi M., Le Bon S.D., Rodriguez A., et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicentre European study. Eur Arch OtoRhinoLaryngol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K.W., et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard Stoecklin S., Rolland P., Silue Y., Mailles A., Campese C., Simondon A., et al. First cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in France: surveillance, investigations and control measures, January 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.6.2000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DICOM_Lisa C. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé; 2020. COVID-19 : prise en charge en ambulatoire [Internet] [cited 2020 Mar 23; available from: http://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/soins-et-maladies/maladies/maladies-infectieuses/coronavirus/covid-19-informations-aux-professionnels-de-sante/article/covid-19-prise-en-charge-en-ambulatoire] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., Shu H., Xia J., Liu H., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [cited 2020 Mar 22; available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanres/article/PIIS2213-2600(20)30079-5/Abstract] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akerlund A., Bende M., Murphy C. Olfactory threshold and nasal mucosal changes in experimentally induced common cold. Acta Otolaryngol. 1995;115:88–92. doi: 10.3109/00016489509133353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki M., Saito K., Min W.-P., Vladau C., Toida K., Itoh H., et al. Identification of viruses in patients with post-viral olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:272–277. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000249922.37381.1e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee D.Y., Lee W.H., Wee J.H., Kim J.-W. Prognosis of post-viral olfactory loss: follow-up study for longer than one year. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28:419–422. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X.-Y., Dai W.-J., Wu S.-N., Yang X.-Z., Wang H.-G. The occurrence of diarrhea in COVID-19 patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]