Abstract

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a commonly- used treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). However, our understanding of the mechanism by which TMS exerts its antidepressant effect is minimal. Furthermore, we lack brain signals that can be used to predict and track clinical outcome. Such signals would allow for treatment stratification and optimization. Here, we performed a randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial and measured electrophysiological, neuroimaging, and clinical changes before and after rTMS. Patients (N = 36) were randomized to receive either active or sham rTMS to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) for 20 consecutive weekdays. To capture the rTMS-driven changes in connectivity and causal excitability, resting fMRI and TMS/EEG were performed before and after the treatment. Baseline causal connectivity differences between depressed patients and healthy controls were also evaluated with concurrent TMS/fMRI. We found that active, but not sham rTMS elicited (1) an increase in dlPFC global connectivity, (2) induction of negative dlPFC-amygdala connectivity, and (3) local and distributed changes in TMS/EEG potentials. Global connectivity changes predicted clinical outcome, while both global connectivity and TMS/EEG changes tracked clinical outcome. In patients but not healthy participants, we observed a perturbed inhibitory effect of the dlPFC on the amygdala. Taken together, rTMS induced lasting connectivity and excitability changes from the site of stimulation, such that after active treatment, the dlPFC appeared better able to engage in top-down control of the amygdala. These measures of network functioning both predicted and tracked clinical outcome, potentially opening the door to treatment optimization.

Subject terms: Depression, Predictive markers

Introduction

Depression is a highly prevalent and serious mental illness, with unsatisfying treatment success rates for even the best-calibrated combinations of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy [1, 2]. Newer treatments such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) may modulate connectivity in and between specific brain networks [3], and may thus enable development of non-invasive therapies that build on our emerging understanding of brain network dysfunction in depression. Clinical trials have demonstrated 10 Hz rTMS to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) to have sham-controlled evidence for antidepressant efficacy [4, 5], resulting in Food and Drug Administration clearance and subsequent broad clinical adoption. Even so, remission rates have been disappointingly low [6, 7]. Moreover, despite evidence of its clinical utility, rTMS was developed without a specific neurophysiological process to modify or a clear sense of its specific anatomical target within the dlPFC, a region we now understand to be highly diverse [8]. Recently, several studies have attempted to resolve this heterogeneity as it relates to rTMS by using task functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [9], individualized brain network mapping [10], and resting-state connectivity [11] (for a review see ref. [3]). While promising, prior studies typically: (1) lack a sham control arm necessary to distinguish intervention effects from factors like placebo responses, and (2) aside from changes in connectivity, fail to use causal brain measurements (e.g., activation in one region causes brain changes in another region) to explain the mechanism underlying rTMS. Optimization of the treatment technique has thus been hindered by our poor mechanistic understanding of the antidepressant effect of rTMS, and the lack of neural circuit signals that predict and track clinical outcome.

To date, neuroimaging work investigating left dlPFC rTMS in depression has used conventional brain measurement (e.g., fMRI or electroencephalography (EEG)) before and after a treatment course (for a review see ref. [12]). These studies generally suggest a change in either frontal or temporal lobe function, activity, or connectivity after rTMS (often also tied to successful clinical outcome) [3, 13]. Regarding frontal lobe changes, rTMS has been shown to normalize within-network DMN hyperconnectivity [14], normalize abnormal dlPFC-medial prefrontal connectivity [14], and predict outcome based on dlPFC-anterior cingulate [9, 15] or anterior cingulate–parietal connectivity [9]. Regarding temporal lobe changes, left dlPFC rTMS has been shown to increase amygdala blood flow [16] and decrease responses to negative faces [17].

In addition to which neuroanatomical targets are relevant for the antidepressant effect of rTMS, a mechanistic understanding of how rTMS exerts its effect on these regions is limited. There is a long-standing notion that 10 Hz rTMS works by increasing net excitability through a long-term potentiation-like (LTP) phenomenon. However, limited evidence exists in humans to support this claim. In fact, recent animal work on rTMS itself (rather than electrically -induced LTP in brain slices) suggests a different mechanism than excitatory LTP: decreased intracortical inhibition. For example, 10 Hz rTMS applied to cat visual cortex resulted in a decrease in the prolonged inhibitory rebound to single TMS pulses, along with evidence of decreased inhibition during visual processing [18]. We also recently demonstrated that a 10-minute application of intracranial electrical cortical stimulation in an rTMS-like 10 Hz fashion suppressed the 20–40 ms stimulation-evoked potential [19]. Given that this potential is thought to be inhibitory in nature [20, 21], these studies suggest that rTMS may elicit changes through a previously unconsidered mechanism of decreased cortical inhibition. One way to understand which regions and neurophysiological processes are altered by rTMS non-invasively is therefore to examine brain activity directly induced by TMS pulses using concurrent fMRI or EEG [22–24]. Concurrent TMS/fMRI can likewise reveal which downstream brain regions are influenced by dlPFC stimulation [24].

To better understand the mechanisms and predictors of 10 Hz rTMS treatment, we conducted a multimodal randomized sham-controlled rTMS study in patients with major depression, and examined changes in resting-state fMRI connectivity (Fig. 2) and TMS/EEG-induced neural responses (Figs. 3 and 4). Additionally, we compared TMS-evoked responses using concurrent TMS/fMRI in patients and controls prior to treatment to determine whether rTMS-induced connectivity changes reflected causally disrupted neural relationships in depression (Fig. 5). Our initial pre-specified hypotheses on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01829165) focused exclusively on concurrent TMS/fMRI; however, equipment failure precluded us from collecting these data for 1.5 years, which included all planned post-treatment measurements. Thus, we were forced to revise the analysis in favor of resting fMRI and TMS/EEG. The overall goals, however, remained the same, including (1) to examine the causal interactions between the dlPFC and other brain regions implicated in depression, and (2) to examine the impact of antidepressant rTMS treatment on these connectivity abnormalities. We hypothesized that 10 Hz left dlPFC rTMS induces connectivity changes specific to the stimulated site in dlPFC, that these changes would be reflected in adjustment of abnormal resting fMRI and TMS/EEG patterns, and that the strength of these effects would predict and track clinical outcome. Together, our results suggest that 10 Hz dlPFC rTMS in depression induces long-lasting, clinically relevant neuromodulatory effects, likely related in part to a strengthening of top-down control from dlPFC to the amygdala.

Materials and methods

The study methods are presented here in brief, with additional detail available in the Supplemental Methods section in the online data supplement. Of note, our study differs from what was pre-registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01829165), because the pre-specified hypotheses relied on concurrent TMS/fMRI data, which we could not gather post-treatment due to equipment failure. The following analysis was designed to take advantage of the multimodal data we were able to collect despite this equipment failure.

Participants, assessments, and inclusion criteria

Eighty-five patients with major depressive disorder were assessed for eligibility (see clinicaltrials.gov registration: NCT01829165 and Fig. S1 for CONSORT diagram). After exclusion based on the criteria outlined below, or dropout prior to intervention, 36 patients gave informed consent to participate in this study, which was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. Three patients declined to participate following randomization but before treatment initiation. In addition, 28 healthy control participants gave informed consent and participated in the same procedures as the depressed patients did pre-treatment (healthy participants were not re-assessed). A structured clinical interview was performed to assess depressive symptoms and other diagnoses. All depressed patients were 18–50-year-old, right handed, and met criteria for DSM-IV defined major depression [25]. Depressed patients were either medication-free or were washed off of their medications for 2 weeks prior to therapy initiation. In order to limit placebo response rates that would diminish active-sham rTMS comparisons, but not enrich for an excessively treatment-resistant population [26], inclusion criteria included failure of one adequate antidepressant trial within-episode [27], but not > 3 failures.

Randomization

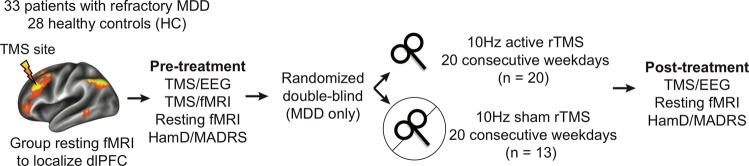

After initial assessments and baseline resting fMRI, TMS/EEG, and TMS/fMRI, patients were randomized to active (N = 20) or sham (N = 13) rTMS treatment in a 2:1 ratio within a double-blind sham-controlled design (Fig. 1). See the CONSORT chart in Fig. S1 for further details.

Fig. 1. Experimental protocol.

Healthy controls (HCs) and patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) were enrolled and underwent baseline resting-state fMRI, concurrent TMS/EEG, and concurrent TMS/fMRI, as well as clinical assessment. Patients were then randomized in a double-blind fashion to daily 10 Hz active or sham rTMS targeting the left dlPFC. At least 24 h after the last rTMS session, patients underwent a post-treatment resting-state fMRI, concurrent TMS/EEG, and clinical assessment.

rTMS treatment

Active rTMS treatment consisted of daily 10 Hz rTMS (4 s on, 26 s off) for 37.5 min (3000 pulses) for 4 consecutive weeks, and used neuronavigation to target the dlPFC node of the frontoparietal control network (FPCN; see Supplemental Methods). Sham rTMS was performed with a flipped TMS coil and electrical scalp stimulation to mimic rTMS.

Post-treatment assessment

Twenty-four hours after the last rTMS session, a post-treatment clinical assessment, resting fMRI, and TMS/EEG paradigms were performed to compare with pre-treatment.

Resting-state fMRI—functional connectivity analysis

All functional connectivity analyses were performed using standard tools in the CONN toolbox [28] (www.nitrc.org/projects/conn), after removing unwanted motion, physiological, and other artifactual effects from the BOLD signal as described in Supplemental Methods. We focused on connectivity from the target of TMS in the left dlPFC node of the FPCN, but as a control, we also calculated connectivity from ten other randomly selected prefrontal regions. We used linear mixed models to assess whether rTMS treatment, compared with sham, modulated connectivity from the site of stimulation, and whether connectivity values could predict clinical responses to treatment. Our connectivity metrics and statistical approaches are described in detail in Supplemental Methods.

Concurrent TMS/EEG

To assess causal patterns of brain excitability before and after rTMS, we performed concurrent TMS/EEG mapping (N = 16 active rTMS, 12 sham rTMS, 28 total). EEG was recorded as single TMS pulses were applied to dlPFC nodes in the right and left frontoparietal control network (FPCN) and the left ventral attention network (VAN), as well as primary visual cortex (V1). Following artifact rejection, TMS-evoked potentials were quantified for each time window and electrode (see Supplemental Methods for further details). To compare the effects of treatment arm (active/sham rTMS) and time (pre/post-rTMS), we performed linear mixed model analysis within a full intent-to-treat framework to accommodate data loss or treatment dropout. In addition, we compared the effects of stimulation site and time using the same framework. For both analyses, a cluster-based non-parametric test was used to correct for multiple comparisons across evoked potential time windows and brain region.

Concurrent TMS/fMRI

To investigate normative patterns of downstream influence in brain regions identified by our resting fMRI analysis as demonstrating treatment-related change, a cohort of the depressed patients (N = 20) and a matched healthy cohort (N = 21) underwent a concurrent TMS/fMRI scanning session conducted according to established protocols [24]. Single pulses were applied to either the FPCN or VAN left dlPFC nodes, and downstream fMRI BOLD responses were quantified and compared. See the Supplemental Methods section for further details.

Results

Clinical results

Active rTMS led to a significant group reduction in depressive symptoms on the HamD (effect of time; F(1,33) = 26.4, p < 0.001). In each treatment arm, five patients were categorized as clinical responders (50% reduction in clinical symptoms; 5/18 or 27% in active rTMS, 5/13 or 38% in sham rTMS). Consistent with effect size expectations, given the sample size in our multimodal mechanism-focused design, this reduction did not significantly differ across treatment arms (treatment arm × time interaction: F(1,75) = 2.36, p = 0.135; HamDactive = 25.8 → 17.6; ΔHamDactive = −8.25; HamDsham = 25.9 → 15.1; ΔHamDsham = −10.83).

Resting fMRI connectivity

We first used a linear mixed model to test whether rTMS changed the global connectivity of the dlPFC stimulation site, i.e., the average connectivity of the stimulated voxels with the rest of the brain. Doing so revealed a significant treatment arm × time interaction (F(1,52) = 6.54, p = 0.013, Cohen’s d = 0.46, N = 31 Fig. 2a, b). This interaction was driven by a global connectivity increase with active rTMS (posthoc pairwise test, F(1,28) = 7.28, p = 0.012, Cohen’s d = 0.75, N = 18), but no change in connectivity in the sham arm (posthoc pairwise test, F(1,27) = 0.44, p = 0.51, Cohen’s d = 0.29, N = 13). These rTMS-induced connectivity changes brought patients closer, on average, to the connectivity patterns in healthy participants (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Active rTMS modulates functional connectivity from left dlPFC stimulation site, predicting and tracking clinical response.

a Left dlPFC stimulation targets were defined for each individual based on the location of the frontoparietal control network (FPCN). b Treatment arm (active, sham) × time (pre-, post-treatment) effects of rTMS on global functional connectivity from the stimulation site. HC healthy control, MDD major depressive disorder. c Treatment arm × time effects of rTMS on functional connectivity seeded from the dlPFC stimulation site to left amygdala, right amygdala, and right dlPFC. For the amygdala, connectivity in the active rTMS arm no longer differed between patients and healthy individuals after treatment (left amygdala post-treatment t(41) = 0.83, p = 0.41; right amygdala post-treatment: t(41) = −0.23, p = 0.82), whereas it was significantly impaired before treatment (left amygdala t(44) = 4.91, p = 1.32e-5; right amygdala t(44) = 3.07, p = 0.0036). For the right dlPFC, connectivity remained persistently elevated in patients even at the end of active rTMS (pre-treatment t(44) = 4.08, p = 0.00018; post-treatment: t(41) = 2.62, p = 0.01). Peak voxels: left amygdala: −28 −2 −16, Z = −3.00; right amygdala: 30 −2 −18, Z = −3.14; right dlPFC: 46 22 34, Z = −3.31. d Lower baseline left dlPFC global connectivity predicts greater change in HamD scores in the active rTMS arm, illustrated here by a median split on baseline global connectivity values. e Pre-minus-post change in left dlPFC global connectivity in the active rTMS arm correlates with pre-minus-post change in HamD scores.

As a control for spatial specificity, we analyzed global connectivity from ten additional randomly -selected prefrontal seeds, which were not directly targeted by rTMS (Supplemental Fig. 2). When we combined the stimulation site with these ten additional seeds, we found a significant three-way interaction (seed × arm × time; F(43,420) = 2.16, p < 0.001), driven by the strong two-way interaction in the stimulation site. Indeed, when analyzed separately, there were no significant treatment arm × time interactions in any of the other regions (all p > 0.1).

To further understand rTMS-induced changes in dlPFC connectivity, we generated seeded connectivity maps from each patient’s site of stimulation, examining targets across cortico-limbic circuitry implicated in depression (i.e., lateral and medial PFC, insula, and amygdala) [29, 30]. This revealed significant connectivity changes in the bilateral amygdalae and contralateral dlPFC (Fig. 2c, Supplemental Tables 2 and 3, Supplemental Figs. 3 and 4). As above, these active rTMS-induced changes brought patients closer to controls (Fig. 2c; see pairwise statistics in the figure legend). Notably, the normative negative dlPFC-amygdala connectivity was evident only at post-treatment in the active rTMS arm.

We next determined how dlPFC global connectivity related to clinical treatment outcome. Within the active rTMS arm, baseline left dlPFC global connectivity predicted treatment outcome, such that patients with lower pre-treatment connectivity levels showed greater clinical improvement (linear mixed model, global connectivity × time interaction, F(1,31) = 8.52, p = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 1.59; illustrated with a median split in Fig. 2d). Moreover, pre-to-post increases in connectivity correlated negatively with pre-to-post HamD changes, indicating that active rTMS arm patients with the greatest increase in dlPFC global connectivity showed the greatest clinical improvement (r = –0.6, p = 0.01; Fig. 2e). By contrast, connectivity between the site of stimulation and the amygdalae and right dlPFC did not predict or track clinical outcome (prediction p’s > 0.42, tracking p’s > 0.23). Furthermore, within the sham rTMS arm, baseline left dlPFC global connectivity did not predict treatment outcome (F(1,22) = 0.40, p = 0.54, Cohen’s d = 1.21), and changes in connectivity did not correlate with changes in HamD score (r = −0.12, p = 0.72), although these results should be interpreted with caution given low power within the sham arm.

Concurrent TMS/EEG

Next, we asked if there were differential effects of active vs. sham rTMS on the TMS-evoked potential (TEP), a tool to probe the causal neurophysiological influence of a brain region through single TMS pulses (Fig. 3a, b). After correcting for multiple comparisons across the TMS/EEG potentials examined, only the p30 (25–35 ms post-TMS pulse) demonstrated a significant treatment arm × time interaction in the linear mixed model analyses (Fig. 3c, d). Specifically, significant interaction effects were found separately in left frontal (linear mixed model, cluster-level statistic 38.06, p = 0.002, n = 5 electrodes) and parietal (cluster-level statistic 38.06, p = 0.002, n = 4 electrodes) electrodes for the p30 (Fig. 3d). These effects were driven by significant frontal and parietal p30 changes in the active but not sham rTMS arm (within-arm effect of time scalp significance topography plots in Fig. 3g and corresponding time series from significant treatment arm × time clusters in Fig. 3f). As shown in Fig. 3e, active but not sham rTMS reduced (and reversed) the p30 potential. Comparison with p30 responses in healthy individuals revealed that the change with active rTMS in patients was in the direction of normalization of p30 TEPs, similarly for both the frontal and parietal clusters. Finally, while baseline p30 responses in frontal or parietal clusters in active rTMS arm patients did not predict the magnitude of clinical change in linear mixed models, the amount of change in the prefrontal p30 responses with treatment did scale with symptom change. The greater the reduction in prefrontal p30 responses with active rTMS, the greater the associated clinical change (r = 0.72, p = 0.0025; Fig. 3h).

Fig. 3. Daily active but not sham rTMS modulates the TMS/EEG p30 potential.

a Single-pulse TMS/EEG was delivered before and after active and sham rTMS at the left dlPFC treatment site. b Example TEP traces. c Scalp topography of each TMS/EEG potential across all participants. d Treatment arm × time interactions were only found for the p30 (25–35 ms) potential (p < 0.05, cluster-corrected for multiple comparisons). d Scalp topographic plot of the -log(p-value) of this interaction. e TEP time series for the frontal and parietal clusters in d, separated by treatment arm. Green arrow = frontal cluster; blue arrow = parietal cluster. Shaded vertical bar represents the p30 time period. Insert shows 0–50 ms component of the TEP for each group. f Extractions of p30 amplitudes from the significant frontal and parietal clusters, plotting pre- and post-treatment TEPs for each treatment arm, along with p30 amplitudes from the same electrodes in healthy controls (HC). Error-bars represent SEM. g Scalp topographic plots of the main effect of time (pre vs. post) in each treatment arm. h Correlation between pre-minus-post p30 amplitudes in the frontal cluster and pre-minus-post symptoms (HamD) showing that the degree of change in the p30 correlates with the degree of symptom improvement.

Finally, we evaluated the site-specificity of this p30 finding by comparing the change in p30 TEPs after active rTMS at the left FPCN dlPFC to changes at the right FPCN dlPFC, left VAN dlPFC, or V1 stimulation sites. We hypothesized that network changes induced by left FPCN dlPFC rTMS would most likely be observed following TMS/EEG to the treated network (left FPCN) and not other networks. We observed significant stimulation site × time interaction effects in the comparison between the treatment site and all other sites (see Fig. 4), suggesting that p30 suppression after active rTMS was observed only after single pulses to the treatment site. In summary, active rTMS suppressed the p30 potential, and greater rTMS-induced suppression correlated with better clinical outcome.

Fig. 4. Site-specificity of p30 suppression after active rTMS.

a FPCN vs. VAN. Top panel: Location of TMS/EEG stimulation sites in the left dlPFC, corresponding to the FPCN (i.e., site of rTMS treatment) and VAN. Topography of stimulation site (FPCN, VAN) × time (pre, post-active rTMS) interaction (p < 0.05, cluster-corrected, linear mixed model). Middle panel: Estimated marginal means from site × time effect. Bottom panel: TEPs time series from each stimulation site. Error-bars represent SEM. Shaded vertical bar represents the p30 time period. Column with green arrow denotes results from frontal cluster; blue arrow denotes parietal cluster. Shaded vertical bar represents the p30 time period. Insert shows 0–50 ms component of the TEP for each group. We observed significant stimulation site × time interaction effects in the comparison with the left VAN dlPFC (frontal cluster-level statistic 55.78, p = 0.002, n = 5 electrodes; parietal cluster-level 55.78, p = 0.002, n = 2 electrodes). b Similar to a, but for left vs. right FPCN dlPFC stimulation site × time interaction. Significant site × time interaction effects were observed in the comparison between left FPCN dlPFC and the right FPCN dlPFC (frontal cluster-level statistic 35.70, p = 0.002, n = 4 electrodes), c Similar to a, but for left FPCN dlPFC vs. V1 stimulation site × time interaction. Significant site × time interaction effects were observed between left FPCN dlPFC and V1 (frontal cluster cluster-level statistic = 43.01, p = 0.002, n = 4 electrodes).

Concurrent TMS/fMRI

The results above imply that connectivity from the dlPFC to specific downstream regions might underlie the clinical effects of rTMS. Do these regions also show abnormalities in the causal influence of the dlPFC in depressed patients at baseline? To find out, we took advantage of concurrent TMS/fMRI, examining responses in the amygdalae and right dlPFC ROIs identified above following single TMS pulses to the left FPCN dlPFC site. We again used the nearby left VAN dlPFC site as a control for spatial specificity. A linear mixed model revealed a significant interaction between stimulation site (FPCN vs. VAN dlPFC) and group (healthy vs. depressed) (F = 7.50, p = 0.007), but no further interaction with ROI (amygdalae and right dlPFC), suggesting similar effects across ROIs. Indeed, testing for a stimulation site × group interaction separately for each ROI revealed a significant effect in the left amygdala (F(1,39) = 5.34, p = 0.026), right dlPFC (F(1,39) = 5.68, p = 0.022) and a trend in the right amygdala (F(1,39) = 3.47, p = 0.070). In healthy individuals, FPCN dlPFC stimulation led to negative fMRI responses (deactivation) in the amygdala and no change in the right dlPFC (Fig. 5a). By contrast, depressed patients failed to show amygdala deactivation and showed aberrant right dlPFC activation. None of these group differences were evident following left VAN dlPFC stimulation (Fig. 5b) despite the proximity to the stimulation site. In summary, concurrent TMS/fMRI demonstrates that stimulation of left FPCN dlPFC normally deactivates the amygdala, but depressed patients do not show this effect.

Fig. 5. Causal inhibitory influence of the left dlPFC on the amygdalae and right dlPFC is perturbed in patients prior to rTMS.

Concurrent TMS/fMRI response following single-pulse TMS to the a left FPCN dlPFC, or b left VAN dlPFC. TMS responses were extracted from the regions of interest identified in the resting fMRI treatment arm × time interactions displayed in Fig. 2c. Left FPCN dlPFC stimulation resulted in amygdala inhibition in healthy controls (HC), but not in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), an abnormal pattern that was not seen in response to left VAN dlPFC stimulation. For the right dlPFC ROI, activation was seen in MDD but not HC participants, and only when the left FPCN dlPFC was stimulated.

Discussion

To better understand how rTMS treatment in depression modulates brain activity, we performed a randomized, sham-controlled, mechanism-focused clinical trial and measured electrophysiological, neuroimaging, and clinical changes before and after rTMS. Our findings were as follows: (1) Active but not sham rTMS increased dlPFC resting fMRI global connectivity and induced negative connectivity with bilateral amygdala that was not present at baseline, with global connectivity predicting and tracking the degree of clinical change; (2) Active but not sham rTMS suppressed the early TMS-evoked potential (potentially representing cortical inhibition, thus suggesting a post-rTMS reduction in intracortical inhibition), localized to left-sided prefrontal and parietal cortices, with the change in this signal tracking the degree of clinical change; and (3) Depressed patients failed to show healthy inhibition of amygdala activity from single TMS pulses to the dlPFC delivered during concurrent TMS/fMRI. Together, these results suggest that rTMS induces long-lasting neuromodulatory effects, characterized by a reduction of electrophysiological metrics thought to index local intracortical inhibition and a restoration of healthy negative dlPFC-amygdala connectivity. Important limitations to consider in the interpretation of these findings is the small sample (a common limitation of highly multimodal studies), the high placebo rate making it difficult to discern TMS-specific and non-specific factors, the lack of separation between active/sham treatment arms (although not powered for clinical separation), the fact that sham rTMS may have components that are not fully inert, the potential lack of generalizability to more complex clinical samples (e.g., rTMS and assessments performed in a laboratory context in medication-free patients rather than in a clinic context with concurrent medication use), the method of identifying the target TMS site (using normative resting fMRI maps with higher signal-to-noise as opposed to individualized maps with lower signal-to-noise), the fact that equipment failure precluded direct testing of the pre-specified ClinicalTrials.gov hypotheses, and remaining questions about the physiological mechanisms underlying TMS/EEG and fMRI signals.

Ten hertz rTMS may reduce prefrontal intracortical inhibition

While increased excitation through LTP is widely thought to underlie rTMS effects, our evidence suggests that rTMS may instead reduce prefrontal intracortical inhibition, leading to clinical improvement in depressive symptoms. Indeed, rTMS in animal experimental settings has been shown to decrease interneuron firing [31] and reduce the inhibitory notch commonly seen in visual evoked activity [18]. We recently reported that 10 Hz prefrontal intracranial electrical stimulation in humans suppressed the intracranial p30 evoked response [19, 32]. These results are consistent with the TMS/EEG findings reported here, where active rTMS suppressed the p30 specifically in the stimulated network. Importantly, we observed changes specific to early potentials, stimulation site, and treatment arm, all of which controls for non-specific effects of TMS [33]. While the neurophysiological mechanisms of other TMS/EEG potentials are clearer than for the p30, the reduction in the p30 may reflect a reduction in GABA-Aergic inhibition. Electrical stimulation in slices [20], pharmacological manipulation in humans [21], and paired -pulse human TMS experiments [34] have been linked to GABA-Aergic activity. Therefore, rTMS may elicit neural facilitation due to decreased prefrontal intracortical inhibition rather than through LTP. Future work replicating these findings in a larger sample and linking human p30 results to animal model and pharmacologic investigations are necessary to further elucidate this critical mechanistic question.

Changes in dlPFC-amygdala connectivity

Using resting fMRI to examine long-range changes in connectivity, we found that active but not sham rTMS increased global dlPFC connectivity. Associated with this global connectivity increase was an enhancement of dlPFC-amygdala negative connectivity. Thus, while our EEG findings may represent decreased local inhibition around the dlPFC, our resting fMRI findings may represent enhanced inhibition from the dlPFC to the amygdala. In other words, if these findings replicate in future larger studies, rTMS may strengthen the ability of the dlPFC to exert top-down control elsewhere in the brain, particularly in the amygdala.

Consistent with our resting fMRI results, we found that healthy controls showed greater left amygdala deactivation than depressed patients following single TMS pulses to left dlPFC. This lack of amygdala deactivation in patients may arise from several scenarios, including dysregulated dlPFC-amygdala coupling, higher baseline levels of amygdala activation not effectively decreased via dlPFC control, or a shift in control mechanisms such that the amygdala is causally influenced by a different region in patients relative to healthy controls. There may be other regions mediating this functional link, and it is possible that these mediating regions underlie the difference between patients and healthy controls.

Our findings are consistent with studies suggesting that dlPFC-amygdala connectivity is altered in MDD [35–37], and that rTMS normalizes connectivity patterns [38]. We previously showed that rTMS decreases FPCN hyperconnectivity (which includes the dlPFC stimulation site) and induces stronger dlPFC-DMN-negative connectivity [14]. As the prior study did not include a sham arm, it is difficult to disentangle the effect of rTMS from sham. Here, we found the major change distinguishing active from sham rTMS was in dlPFC-amygdala connectivity. Treatment enhanced negative connectivity between these two sites. Further sham-controlled studies will be needed to replicate this finding and explore its consequences for cognitive and emotional functioning. It is notable that we were unable to replicate previous studies, suggesting rTMS weakens connectivity between the dlPFC and subgenual cingulate [39].

Predicting and tracking clinical response to rTMS

Both our EEG-based p30 and fMRI-based global connectivity markers related to HamD change. Depressed patients with low-dlPFC resting global connectivity at baseline improved to a greater degree following rTMS than those with high-dlPFC connectivity. Furthermore, the greater the enhancement of fMRI global connectivity or p30 suppression, the greater the clinical improvement. It is worth noting that these relationships were driven by a small subset of patients who responded well to rTMS treatment. Interestingly, although baseline global connectivity predicted clinical response, baseline dlPFC-amygdala connectivity did not, suggesting that some of the clinical benefit might arise from enhancing connectivity with other regions. Additionally, the dissociation between the specific fMRI and TMS/EEG findings in the active rTMS arm, and the similar clinical results in both the active and sham rTMS arms, is noteworthy. This may reflect the lower sample size in the sham group (and thus less likely to demonstrate significant effects) or the specific neurophysiological effects of active rTMS that may not directly relate to clinical effects. Finally, this study was powered to detect a medium effect size for our primary group × time analyses on brain function. Thus, some analyses, particularly those of individual differences in brain-clinical benefit relationships, were less well-powered and should be interpreted with caution. Larger studies are needed to determine the external validity of these brain-symptoms relationships and to explore the neural basis of responders in the sham rTMS group. Future work with TMS/fMRI measurements before and after active vs. sham rTMS will also be necessary to address causal network abnormalities, as we had originally set out to do in our ClinicalTrials.gov registration.

Future work

In addition to addressing some of the domains in which current knowledge is lacking regarding how to best interpret resting fMRI and TMS/EEG findings, our results suggest that future work focusing on target engagement and dose–response in the manner pursued here, with the proper sham controls and multimodal measurements, could provide the mechanistic basis for second-generation personalized brain stimulation.

Funding and disclosure

AE was supported by a Dana Foundation grant and NIH grant DP1 MH116506. NE was supported by NIH T32 MH019908. CJK was supported by the NIH Early Independence Award DP5 OD028128, NIMH K23 MH11846601, the Stanford Society of Physician Scholars Collaborative Research Fellowship and the Alpha Omega Alpha Postgraduate Research Award. GAF was supported by NIMH grant T32 MH019938 and the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs. AE holds equity at Mindstrong Health and Akili Interactive for unrelated work. The other authors have no financial disclosures. As of November 1, 2019 AE also received salary and equity from Alto Neuroscience. As of December 16, 2019 CJK received salary and equity from Alto Neuroscience. WW was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61876063 and No. 61836003). The other authors have no financial disclosures.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are enormously indebted to the patients who participated in this study. We thank Jillian Autea for clinical trial coordination.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Neir Eshel, Corey J. Keller, Wei Wu, Jing Jiang

Change history

2/26/2020

This article has been updated to change Figures 1 and 2 to colour.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41386-020-0633-z).

References

- 1.Sinyor M, Schaffer A, Levitt A. The sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression (STAR*D) trial: a review. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:126–35. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thase ME. The need for clinically relevant research on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:221–4. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v62n0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noda Y, Silverstein WK, Barr MS, Vila-Rodriguez F, Downar J, Rajji TK, et al. Neurobiological mechanisms of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in depression: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2015;45:3411–32. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berlim MT, van den Eynde F, Tovar-Perdomo S, Daskalakis ZJ. Response, remission and drop-out rates following high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treating major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham-controlled trials. Psychol Med. 2014;44:225–39. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE, Anderson RJ, Daskalakis ZJ. A study of the pattern of response to rTMS treatment in depression. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:746–53. doi: 10.1002/da.22503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George MS, Lisanby SH, Avery D, McDonald WM, Durkalski V, Pavlicova M, et al. Daily left prefrontal transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy for major depressive disorder: a sham-controlled randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:507–16. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, Sampson S, Isenberg KE, Nahas Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1208–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasser MF, Coalson TS, Robinson EC, Hacker CD, Harwell J, Yacoub E, et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature. 2016;536:171–8. doi: 10.1038/nature18933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor SF, Ho SS, Abagis T, Angstadt M, Maixner DF, Welsh RC, et al. Changes in brain connectivity during a sham-controlled, transcranial magnetic stimulation trial for depression. J Affect Disord. 2018;232:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddiqi SH, Trapp NT, Hacker CD, Laumann TO, Kandala S, Hong X, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation with resting-state network targeting for treatment-resistant depression in traumatic brain injury: a randomized, controlled, double-blinded pilot study. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36:1361–74. doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ning L, Makris N, Camprodon JA, Rathi Y. Limits and reproducibility of resting-state functional MRI definition of DLPFC targets for neuromodulation. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Philip NS, Barredo J, Aiken E, Carpenter LL. Neuroimaging mechanisms of therapeutic transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2018;3:211–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downar J, Geraci J, Salomons TV, Dunlop K, Wheeler S, McAndrews MP, et al. Anhedonia and reward-circuit connectivity distinguish nonresponders from responders to dorsomedial prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:176–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liston C, Chen AC, Zebley BD, Drysdale AT, Gordon R, Leuchter B, et al. Default mode network mechanisms of transcranial magnetic stimulation in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox MD, Buckner RL, White MP, Greicius MD, Pascual-Leone A. Efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation targets for depression is related to intrinsic functional connectivity with the subgenual cingulate. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speer AM, Kimbrell TA, Wassermann EM, D Repella J, Willis MW, Herscovitch P, et al. Opposite effects of high and low frequency rTMS on regional brain activity in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:1133–41. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baeken C, De Raedt R, Van Schuerbeek P, Vanderhasselt MA, De Mey J, Bossuyt A, et al. Right prefrontal HF-rTMS attenuates right amygdala processing of negatively valenced emotional stimuli in healthy females. Behav Brain Res. 2010;214:450–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozyrev V, Eysel UT, Jancke D. Voltage-sensitive dye imaging of transcranial magnetic stimulation-induced intracortical dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:13553–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405508111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller CJ, Huang Y, Herrero JL, Fini M, Du V, Lado FA, et al. Induction and quantification of excitability changes in human cortical networks. J Neurosci. 2018;38:5384–98. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1088-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connors BW, Malenka RC, Silva LR. Two inhibitory postsynaptic potentials, and GABAA and GABAB receptor-mediated responses in neocortex of rat and cat. J Physiol. 1988;406:443–68. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Premoli I, Castellanos N, Rivolta D, Belardinelli P, Bajo R, Zipser C, et al. TMS-EEG signatures of GABAergic neurotransmission in the human cortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34:5603–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5089-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerwin LJ, Keller CJ, Wu W, Narayan M, Etkin A. Test-retest reliability of transcranial magnetic stimulation EEG evoked potentials. Brain Stimul. 2018;11:536–44. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu W, Keller CJ, Rogasch NC, Longwell P, Shpigel E, Rolle CE, et al. ARTIST: a fully automated artifact rejection algorithm for single-pulse TMS-EEG data. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39:1607–25. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen AC, Oathes DJ, Chang C, Bradley T, Zhou ZW, Williams LM, et al. Causal interactions between fronto-parietal central executive and default-mode networks in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:19944–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311772110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lisanby SH, Husain MM, Rosenquist PB, Maixner D, Gutierrez R, Krystal A, et al. Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: clinical predictors of outcome in a multisite, randomized controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacol: Off Publ Am Coll Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;34:522–34. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prudic J, Haskett RF, Mulsant B, Malone KM, Pettinati HM, Stephens S, et al. Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ECT. Am J psychiatry. 1996;153:985–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Nieto-Castanon A. Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2012;2:125–41. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalgleish T. The emotional brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:583–9. doi: 10.1038/nrn1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fonzo GA, Goodkind MS, Oathes DJ, Zaiko YV, Harvey M, Peng KK, et al. Selective effects of psychotherapy on frontopolar cortical function in PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:1175–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16091073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenz M, Galanis C, Muller-Dahlhaus F, Opitz A, Wierenga CJ, Szabo G, et al. Repetitive magnetic stimulation induces plasticity of inhibitory synapses. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10020. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Y, Hajnal B, Entz L, Fabo D, Herrero JL, Mehta AD, et al. Intracortical dynamics underlying repetitive stimulation predicts changes in network connectivity. J Neurosci. 2019;39:6122–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0535-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conde V, Tomasevic L, Akopian I, Stanek K, Saturnino GB, Thielscher A, et al. The non-transcranial TMS-evoked potential is an inherent source of ambiguity in TMS-EEG studies. Neuroimage. 2018;185:300–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cash RF, Noda Y, Zomorrodi R, Radhu N, Farzan F, Rajji TK, et al. Characterization of Glutamatergic and GABAA-mediated neurotransmission in motor and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex using paired-pulse TMS-EEG. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:502–11. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dannlowski U, Ohrmann P, Konrad C, Domschke K, Bauer J, Kugel H, et al. Reduced amygdala-prefrontal coupling in major depression: association with MAOA genotype and illness severity. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:11–22. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708008973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erk S, Mikschl A, Stier S, Ciaramidaro A, Gapp V, Weber B, et al. Acute and sustained effects of cognitive emotion regulation in major depression. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15726–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1856-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant MM, White D, Hadley J, Hutcheson N, Shelton R, Sreenivasan K, et al. Early life trauma and directional brain connectivity within major depression. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:4815–26. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson RJ, Hoy KE, Daskalakis ZJ, Fitzgerald PB. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment resistant depression: Re-establishing connections. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016;127:3394–405. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pizzagalli DA. Frontocingulate dysfunction in depression: toward biomarkers of treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:183–206. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.