Ebola virus (EBOV) causes a severe fever with high case fatality rates and, so far, no available specific therapy. Understanding the interplay between viral and host proteins is important to identify new therapeutic approaches. VP24 is one of the essential nucleocapsid components and is necessary to regulate viral RNA synthesis and condense viral nucleocapsids before their transport to the plasma membrane. Our functional analyses of the YxxL motif in VP24 suggested that it serves as an interface between nucleocapsid-like structures (NCLSs) and cellular proteins, promoting intracellular transport of NCLSs in an Alix-independent manner. Moreover, the YxxL motif is necessary for the inhibitory function of VP24 in viral RNA synthesis. A failure to rescue EBOV encoding VP24 with a mutated YxxL motif indicated that the integrity of the YxxL motif is essential for EBOV growth. Thus, this motif might represent a potential target for antiviral interference.

KEYWORDS: Ebola virus, VP24, late-domain YxxL, Alix, nucleocapsid-like structure, transport, viral transcription and replication

ABSTRACT

While it is well appreciated that late domains in the viral matrix proteins are crucial to mediate efficient virus budding, little is known about roles of late domains in the viral nucleocapsid proteins. Here, we characterized the functional relevance of a YxxL motif with potential late-domain function in the Ebola virus nucleocapsid protein VP24. Mutations in the YxxL motif had two opposing effects on the functions of VP24. On the one hand, the mutation affected the regulatory function of VP24 in viral RNA transcription and replication, which correlated with an increased incorporation of minigenomes into released transcription- and replication-competent virus-like particles (trVLPs). Consequently, cells infected with those trVLPs showed higher levels of viral transcription. On the other hand, mutations of the YxxL motif greatly impaired the intracellular transport of nucleocapsid-like structures (NCLSs) composed of the viral proteins NP, VP35, and VP24 and the length of released trVLPs. Attempts to rescue recombinant Ebola virus expressing YxxL-deficient VP24 failed, underlining the importance of this motif for the viral life cycle.

IMPORTANCE Ebola virus (EBOV) causes a severe fever with high case fatality rates and, so far, no available specific therapy. Understanding the interplay between viral and host proteins is important to identify new therapeutic approaches. VP24 is one of the essential nucleocapsid components and is necessary to regulate viral RNA synthesis and condense viral nucleocapsids before their transport to the plasma membrane. Our functional analyses of the YxxL motif in VP24 suggested that it serves as an interface between nucleocapsid-like structures (NCLSs) and cellular proteins, promoting intracellular transport of NCLSs in an Alix-independent manner. Moreover, the YxxL motif is necessary for the inhibitory function of VP24 in viral RNA synthesis. A failure to rescue EBOV encoding VP24 with a mutated YxxL motif indicated that the integrity of the YxxL motif is essential for EBOV growth. Thus, this motif might represent a potential target for antiviral interference.

INTRODUCTION

Ebola virus (EBOV) is a highly pathogenic zoonotic pathogen and belongs to the family Filoviridae (1). In humans, EBOV and the closely related Marburg virus (MARV) cause severe hemorrhagic fever with high case fatality rates. The largest-ever EBOV epidemic in West Africa ended in 2016 after nearly 3 years, with more than 28,000 cases and more than 11,000 deaths (https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html). Since then, further epidemics of EBOV have been reported in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2). Despite significant efforts to develop anti-EBOV drugs, there are still no approved therapeutics for the Ebola disease (3, 4), while a new vaccine based on a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus has been approved recently (https://ec.europa.eu/cyprus/news/20191112_en).

The tetrapeptide motifs PPxY, P(T/S)AP, and YxxL, collectively termed viral late (L) domains, have been identified in matrix and surface proteins of several enveloped viruses (5–9). It has been shown that viral L domains provide coopting with the components of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) to enhance viral budding (10, 11). For instance, the PPxY motif in the matrix protein VP40 of EBOV or MARV has been shown to interact with Nedd 4 and Nedd 4-like E3 ubiquitin ligases (12–15). The PTAP motif within the p6 domain of Gag binds to the cellular protein Tsg101, thereby facilitating the final stage of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) release (16). Finally, the YxxL motifs in the viral matrix protein of Sendai virus (Paramyxoviridae) or Mopeia virus (Arenaviridae) (17, 18) or in the p6 domain of HIV-1 Gag (19) have been shown to interact with Alix and thus promote virus budding.

While L domains have also been identified in viral nucleocapsid proteins, only limited information is available regarding their function (9, 20). For arenaviruses, it has been demonstrated that a YxxL motif in the nucleoprotein (NP) of Tacaribe virus supports viral release, probably by recruiting Alix to the sites of budding (9), and the YxxL motif in NP of Mopeia virus mediates the incorporation of NP into virus-like particles (21). A PSAP motif in MARV NP mediates binding to Tsg101, enabling efficient actin-dependent transport of nucleocapsids to the budding sites (20, 22). These studies suggest that L domains within viral nucleocapsid proteins might coopt ESCRT proteins to support different steps of viral assembly. In particular, the transport of viral nucleocapsid complexes from the site of synthesis to the site of budding might be supported by the L domains of nucleocapsid proteins.

In the present study, we addressed the question of whether the tetrapeptide motif YxxL located at positions 172 to 175 in the EBOV nucleocapsid protein VP24 indeed has functional relevance for the assembly and budding of virions.

The function of EBOV VP24, a protein of 250 amino acids, is not well understood, in part because most other mononegaviruses do not express analogues of this protein, with a possible exception of nyaviruses (23). In addition, structure-function studies of VP24 are difficult since even minor modifications, such as epitope tagging of VP24 or deletion of a few amino acid residues from either the N- or C-terminal end, can induce significant functional alterations (24, 25). EBOV VP24 was previously considered to be a minor matrix protein (26–28). Recently, several studies demonstrated that VP24 is a structural component of the nucleocapsid complex (29–32). In addition, VP24 interferes with the activation of innate immune responses (33–39). While VP24 is not required for the transcription and replication of EBOV-specific minigenomes, it strongly inhibits both processes (24, 28, 40). Moreover, a recent study showed that a complex of NP, VP35, and VP24 was necessary and sufficient to form nucleocapsid-like structures (NCLSs) that were transported to the plasma membrane by the polymerization of actin (41). Since none of these three viral nucleocapsid proteins alone showed directed long-distance transport, it was suggested that the complex formation is necessary for the interaction of NCLSs with the actin cytoskeleton (41).

The present study demonstrated that the integrity of the YxxL motif in VP24 was important for the interaction with the cellular protein Alix. However, mutations of the YxxL motif in VP24 influenced neither the incorporation of nucleocapsid proteins into transcription- and replication-competent virus-like particles (trVLPs) nor the budding of trVLPs. In contrast, mutation of the YxxL motif in VP24 influenced the following two processes: first, the inhibitory function of VP24 in viral RNA transcription and replication was relieved, and second, the movement of transport-competent NCLSs was inhibited.

RESULTS

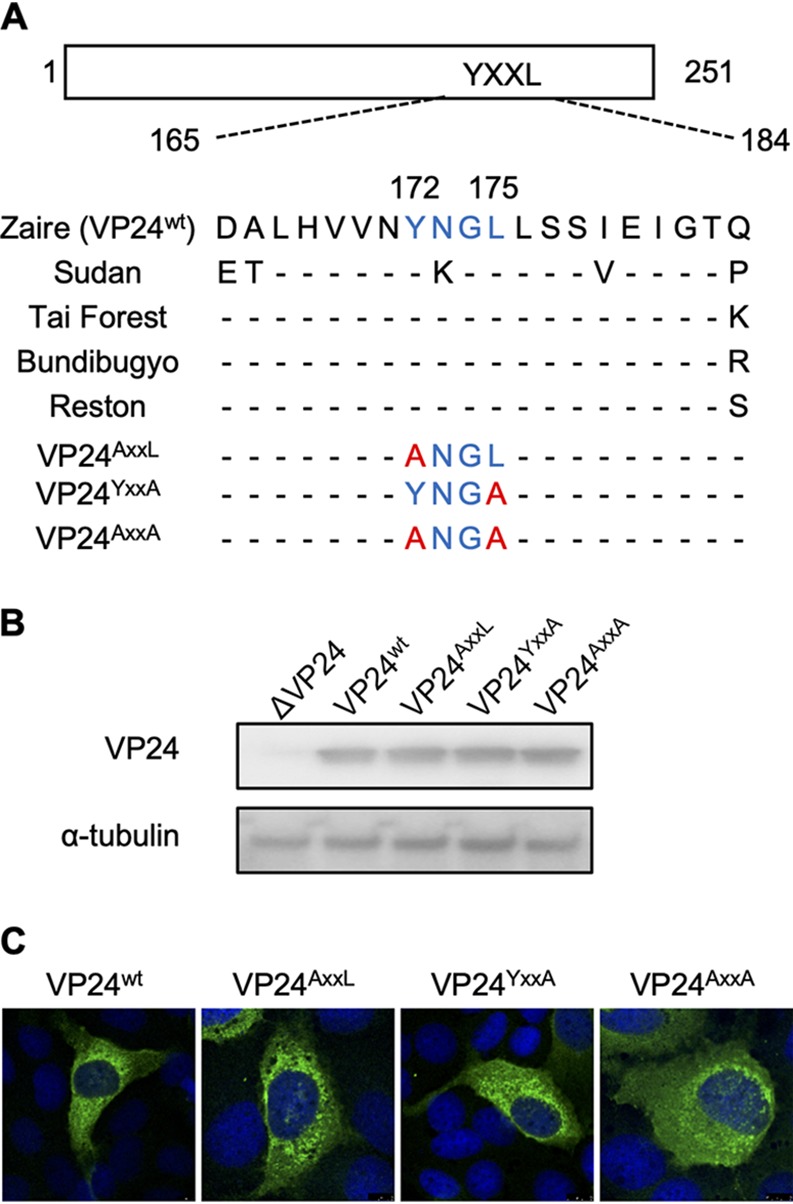

Expression of VP24 constructs with mutations in the YxxL motif.

EBOV VP24 has a conserved YxxL motif in its C-terminal region at positions 172 to 175 (Fig. 1A). In order to evaluate the functional significance of the YxxL motif in VP24, we generated three mutants containing either a tyrosine-to-alanine exchange at position 172 (VP24AxxL), a leucine-to-alanine exchange at position 175 (VP24YxxA), or an exchange of both tyrosine and leucine to alanine (VP24AxxA). The migration patterns of the VP24 mutants analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and their intracellular distributions were similar to that of wild-type VP24 (VP24wt), suggesting that the mutation of the YxxL motif did not significantly affect the folding and expression of VP24 (Fig. 1B and C).

FIG 1.

Expression of VP24 constructs containing mutations in the YxxL motif. (A) Schematic representation of VP24 amino acid sequences of the various Ebola viruses and VP24 mutants from positions 165 to 184. The putative YxxL motif is indicated in blue, and the mutated amino acids are shown in red. (B) Huh-7 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding either VP24wt or VP24 mutants. Cells were harvested at 24 h p.t., lysed, and subsequently subjected to Western blot analysis using an anti-VP24 antibody and alpha-tubulin as a control. (C) Huh-7 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding each VP24 construct. Anti-VP24 antibody signals were analyzed by confocal microscopy. DAPI was used to visualize the nucleus.

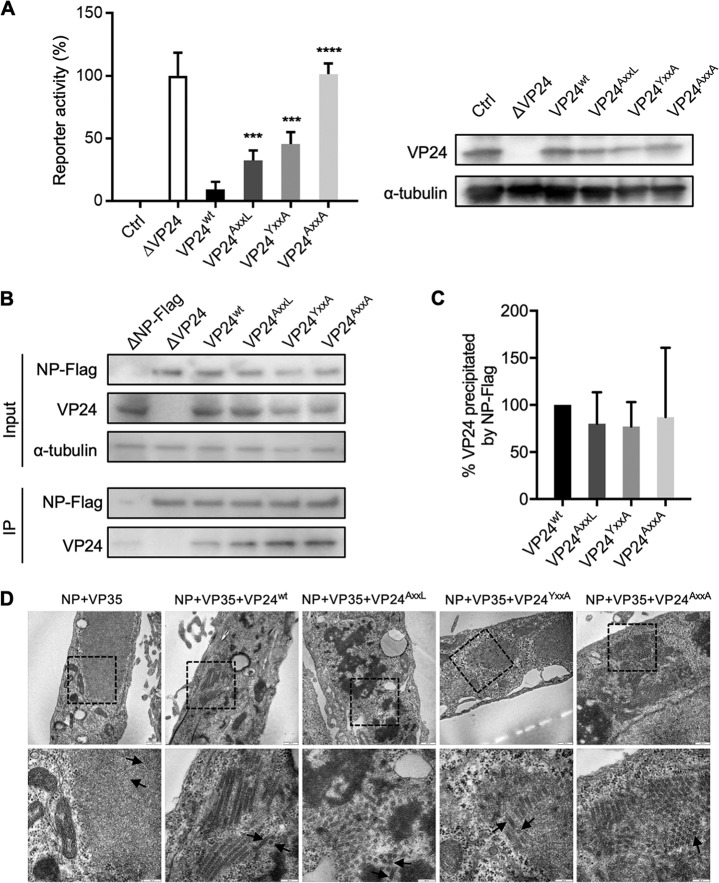

Mutations in the YxxL motif of VP24 influence minigenome transcription/replication and not the condensation of NCLSs.

VP24 has a strong regulatory function on the transcription and replication of EBOV minigenomes (24, 28). This effect is considered to be induced by VP24’s ability to interact with NP, leading to the condensation of the helical nucleocapsid and preventing further usage of the nucleocapsid as a template for RNA synthesis (24, 25, 42, 43). To address the question of whether the YxxL motif is important for this regulatory function, we analyzed YxxL mutants of VP24 in minigenome transcription/replication assays. Cells were transfected with the plasmids encoding the components of the minigenome assay (NP, L, VP30, VP35, EBOV-specific minigenome, and T7 polymerase), as well as the plasmids encoding VP24wt or one of the VP24 mutants (24). The reporter gene activity was reduced to 9% by the expression of VP24wt and to 36% and 46% upon the expression of VP24AxxL and VP24YxxA, respectively (Fig. 2A). The VP24AxxA mutant almost completely lost its ability to inhibit reporter gene activity, indicating that the integrity of the YxxL motif of VP24 is essential to downregulate viral RNA transcription and replication (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

Influence of mutations in the YxxL motif of VP24 on minigenome transcription/replication and NCLS assembly. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with either of the VP24 constructs together with the minigenome assay components. Protein expression of VP24 and alpha-tubulin was analyzed by Western blotting. At 48 h p.t., cells were lysed, and the reporter gene activity was measured. The relative reporter activity without expression of VP24wt was set to 100%. The negative control was without expression of VP30 (Ctrl) and displayed the background of the assay. The mean and SD values of the results from three independent experiments are shown. The asterisks indicate statistical significance, as follows: ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (B and C) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis. HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding Flag-tagged NP and one of the VP24 constructs. At 48 h p.t., the cells were lysed, and protein complexes were precipitated using anti-Flag M2 agarose. An aliquot of cell lysate (input) was collected before precipitation. (B) Western blot analysis was performed using Flag-, VP24-, and alpha-tubulin-specific antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitation. (C) The relative amounts of precipitated VP24 are displayed. The intensities of the bands of precipitated VP24 were normalized to the intensities of the respective bands in the cell lysates. The precipitants of VP24wt were set to 100%. The mean and SD values of the results from three independent experiments are shown. (D) Huh-7 cells expressing NP, VP35, and with the addition of one of the VP24 constructs were fixed at 24 h p.t. and processed for transmission electron microscopy analyses. The absence or presence of electron-dense walls in the tubular-like NCLSs is indicated by arrows on the transversal or longitudinal sections of NCLSs. The boxed areas in the upper images were enlarged and are shown in the lower images. Scale bars are as follows: upper images = 500 nm, lower images = 200 nm.

To reveal whether the defective regulatory function of the VP24 mutants is induced by an impaired interaction between VP24 and NP, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays using lysates of cells expressing one of the VP24 constructs and Flag-tagged NP. The results demonstrated that mutations of the YxxL motif had no influence on the association between VP24 and NP (Fig. 2B and C).

To analyze whether the VP24 mutants are able to condense nucleocapsid-like structures formed by NP and VP35, transmission electron microscopy was performed. Tubular-like structures with electron-dense walls representing condensed nucleocapsids were detected in the presence of VP24wt and the VP24 mutants, respectively (Fig. 2D, arrows). Notably, these data indicated that the VP24-mediated downregulation of the viral polymerase activity is not dependent on the condensation of the nucleocapsids.

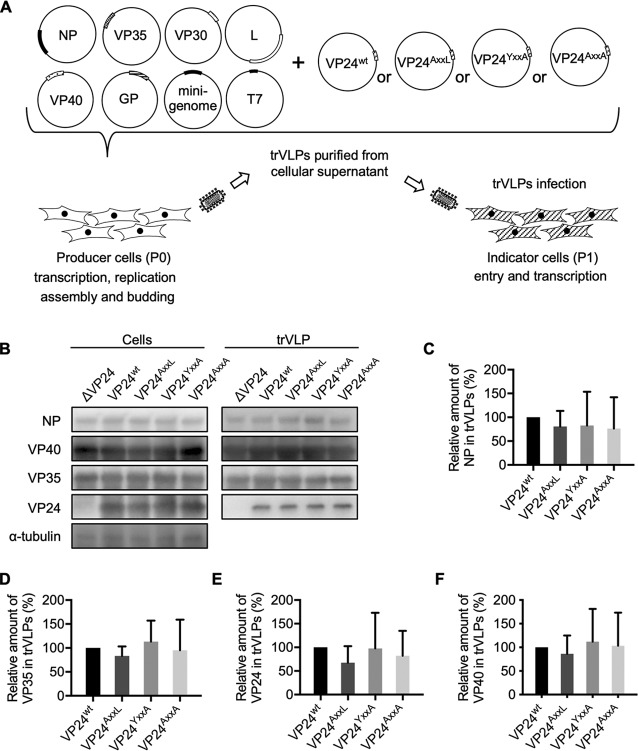

Mutation of the YxxL motif in VP24 does not influence the incorporation of viral proteins into trVLPs.

Knockdown of EBOV VP24 impaired nucleocapsid assembly and prevented virus replication (44), whereas budding of VLPs, which was induced by coexpression of the EBOV matrix protein VP40, was not influenced by VP24 (31, 45). These data suggest a supportive role of VP24 at early stages of virus assembly rather than at the budding stage. To investigate the functional importance of VP24’s YxxL motif for virion assembly and release processes, we used an EBOV-specific transcription- and replication-competent virus-like particle (trVLP) assay (46–48). The producer (P0) cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the components of the minigenome assay, as well as plasmids encoding VP40, GP, and VP24wt or one of the VP24 mutants (Fig. 3A). The ectopic expression of these components in P0 cells resulted in the formation of transcription- and replication-competent viral ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, which serve as the template for transcription and translation of the reporter protein (Renilla luciferase). In addition, coating of the RNP complexes at a VP40- and GP-enriched plasma membrane resulted in the formation of trVLPs which were released into the supernatant of P0 cells. The trVLPs were purified from the cell supernatants at 72 hours posttransfection (h p.t.), and the viral proteins in the cell lysates and in the released trVLPs were analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 3B). The relative incorporation efficiency of viral proteins into trVLPs was determined based on the ratios of band intensities of a given viral protein in the trVLPs and cell lysates (Fig. 3C to F). The relative amounts of NP, VP35, VP24, and VP40 incorporated into trVLPs were not significantly altered upon coexpression of the VP24 mutants. This result suggested that the YxxL motif in VP24 had no impact on the incorporation of viral proteins into trVLPs and did not function as an authentic late-domain-like motif.

FIG 3.

Mutation of the YxxL motif in VP24 does not influence the incorporation of viral proteins into trVLPs. (A) Schematic representation of the trVLP assay. The producer (P0) cells were transfected with plasmids that encode the trVLP components. In the P0 cells, minigenome RNP transcription/replication, assembly, and budding of trVLPs were performed. The purified trVLPs were used for infection of indicator (P1) cells. (B to F) HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the components of the trVLP assay (NP, VP35, VP30, VP40, GP, L, EBOV-specific minigenome, T7 polymerase, and either of the VP24 constructs). Cells were lysed at 72 h p.t., and trVLPs were purified from the supernatants of transfected cells by ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion. (B) Cell lysates and purified trVLPs were processed for SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using NP-, VP40-, VP35-, VP24-, and alpha-tubulin-specific antibodies. (C to F) The relative amounts of viral proteins in trVLPs are displayed by plotting the ratios between the band intensities of NP (C), VP35 (D), VP24 (E), and VP40 (F) in trVLPs and cell lysates. The band intensity of VP24wt was set to 100%. The mean and SD values of the results from three independent experiments are shown.

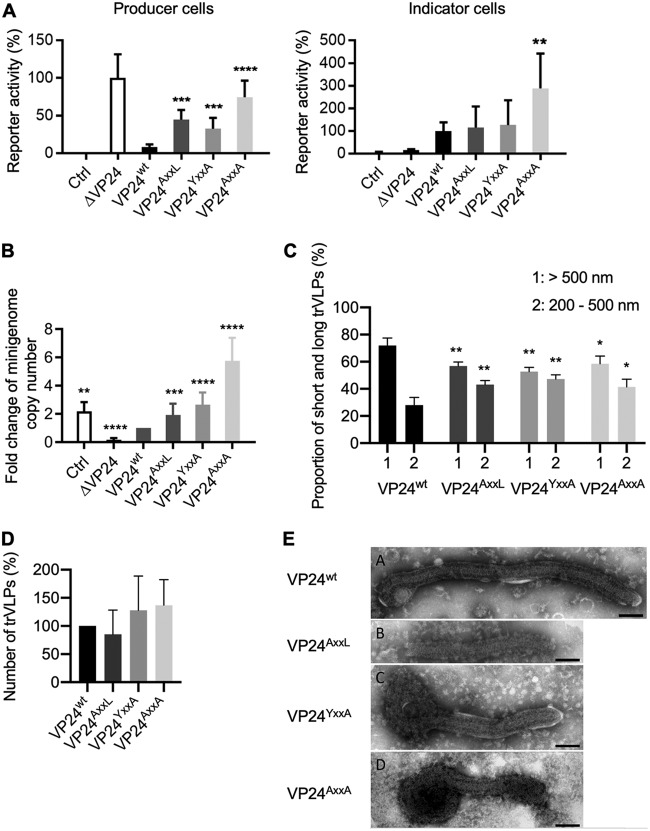

Mutation of the YxxL motif in VP24 increases the infectivity of trVLPs.

We then analyzed the influence of mutations in the YxxL motif on the infectivity of trVLPs. The trVLPs were purified from the supernatant of P0 cells and used for infection of naive indicator (P1) cells (Fig. 3A). The measured reporter activity in P1 cells reflects the entry and transcription of the minigenome and, thus, the functionality of the viral RNP complex (47). The reporter activity was measured both in P0 cells, which were lysed at 72 h p.t., and in P1 cells, which were lysed 48 h after infection with trVLPs. The results demonstrated that the mutation of VP24 bolstered viral RNA synthesis in the producer cells (Fig. 4A), in accordance with the minigenome assay (Fig. 2A). The infection with the trVLPs formed in the presence of VP24AxxA induced a significantly higher reporter activity in P1 cells than that with infection with trVLPs formed in the presence of VP24wt (Fig. 4A, indicator cells). To analyze whether the enhanced reporter gene activity induced by the VP24AxxA-containing trVLPs correlated with the amount of minigenomes incorporated into the particles, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) of purified trVLPs was performed. We detected an increase in the copy number of minigenomes in trVLPs produced in the presence of VP24AxxA (Fig. 4B). These results suggested that enhanced RNA synthesis in the presence of the mutants of VP24 increased the number of minigenomes, which in turn resulted in the incorporation of more NCLSs into trVLPs. Infection with those trVLPs resulted in a higher reporter activity in the indicator cells.

FIG 4.

Mutations of the YxxL motif in VP24 increased the infectivity of trVLPs and increased the percentage of shorter trVLPs. (A) The producer (P0) cells were transfected as described in Fig. 3B, and purified trVLPs were used for infection of indicator cells. The reporter gene activity in the producer cells was measured at 72 h p.t., and in indicator cells at 48 h p.i. The value of reporter activity in VP24wt-expressing cells was set to 100%. The negative control was without the expression of VP30 (Ctrl) and displayed the background of the assay. The mean and SD values of the results from three independent experiments are shown. (B) RNA was isolated from purified trVLPs, and the amount of viral genomic RNA was analyzed by 2-step quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). The negative control was without the expression of VP30 (Ctrl) and displayed the background of the assay. The genome amount of VP24wt was set to 1, and the fold change was analyzed. The mean and SD values of the results from three independent experiments are shown. The asterisks indicate statistical significance, as follows: **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001. (C and D) Electron microscopy (EM) analysis of the length and number of trVLPs produced in the presence of either the VP24wt or VP24 mutants. (C) The length of over 100 particles was measured for every sample in three independent experiments. The percentages of trVLPs ranging from 200 to 500 nm in length and particles above 500 nm were calculated. The asterisks indicate statistical significance in comparison to VP24wt, as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005. (D) The relative numbers of trVLPs produced in the presence of either VP24wt or VP24 mutants. The number of trVLPs in the VP24wt sample was set to 100%. The mean and SD values of the results from three independent experiments are shown. (E) EM images of trVLPs with condensed NCLSs formed in the presence of the VP24wt or VP24 mutants. Scale bars = 100 nm.

The released EBOV-specific trVLPs have various lengths, and it was therefore of interest to test whether the mutation of the YxxL motif influenced the length of trVLPs. We measured the number and length of trVLPs from the supernatant of P0 cells in negatively stained samples using electron microscopy. Among the trVLPs formed in the presence of VP24wt, the ratio of long (>500 nm) to short (<500 nm) particles was 2.6, and in the presence of the VP24 YxxL mutants, the ratio was 1.3, indicating that the YxxL motif of VP24 supported the formation of longer particles (Fig. 4C). The total number of trVLPs was not significantly changed upon mutation of the YxxL motif in VP24 (Fig. 4D). Notably, condensed NCLSs, which represent transport-competent NP-, VP35-, and VP24-positive structures (30, 41), were observed both in trVLPs formed in the presence of VP24wt or VP24 mutants (Fig. 4E). However, the trVLPs formed by VP24wt often contained longer NCLSs (620 ± 400 nm), while trVLPs formed by VP24 mutants held relatively shorter NCLSs (460 ± 230 nm).

Together, these analyses indicated that the mutation of the YxxL motif of VP24 causes the formation and release of shorter trVLPs.

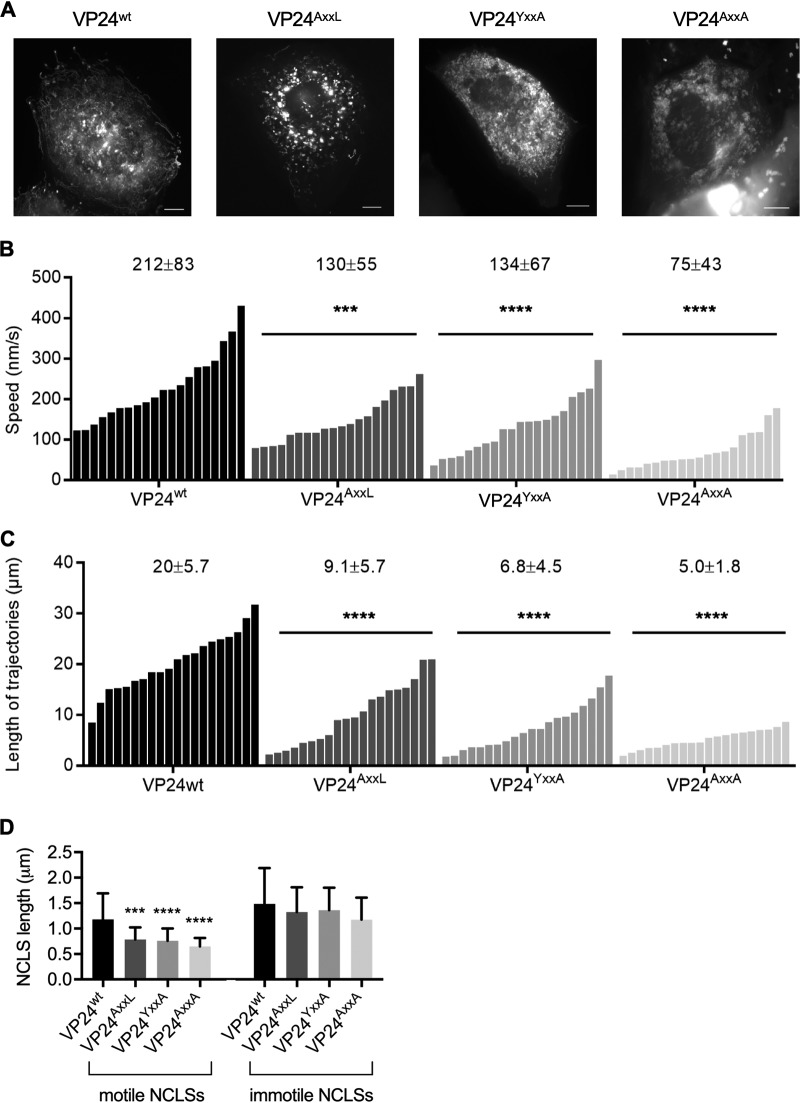

The YxxL motif in VP24 is essential for the transport of NCLSs.

VP24 is one of the three nucleocapsid proteins which are essential and sufficient to form motile NCLSs (41). To reveal whether mutations of the YxxL motif in VP24 influenced the movement of NCLSs, we performed live-cell imaging analyses in Huh-7 cells which, because of their flat shape, are better suited for this purpose than are HEK293 cells. Huh-7 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding VP30-green fluorescent protein (VP30-GFP), NP, VP35, and one of the VP24 constructs, and NCLS trajectories at 20 h p.t. were analyzed. The time-lapse images showed that the mean ± standard deviation (SD) velocity of VP24wt-containing NCLSs was 212 ± 83 nm/s, and the measured trajectories of motile NCLSs had a mean length of 20 μm (Fig. 5A and Movie S1). Both the velocities and the trajectory lengths of motile NCLSs were similar to those in previous reports (41, 49). The mean ± SD velocities of motile NCLSs formed in the presence of VP24AxxL, VP24YxxA, and VP24AxxA were 130 ± 55 nm/s, 134 ± 67 nm/s, and 75 ± 43 nm/s, respectively (Fig. 5B). The average lengths of trajectories measured with NCLSs containing one of the three mutants were 9.1 μm, 6.8 μm, and 5.0 μm, respectively, compared to 20 μm in the presence of VP24wt (Fig. 5C and Movies S2 to S4). In addition, we analyzed the lengths of motile and immotile NCLSs. Importantly, motile NCLSs made of NP, VP35, and VP24AxxL, VP24YxxA, or VP24AxxA were on average significantly shorter than were NCLSs assembled in the presence of VP24wt (Fig. 5D, motile). In contrast, the length of immotile NCLSs showed no significant dependency on the presence of an intact YxxL motif (Fig. 5D, immotile). In summary, mutations in the YxxL motif strongly impaired NCLS’s motility and showed that an intact YxxL motif was indispensable for the intracellular transport of long nucleocapsids, as would be the case for authentic EBOV nucleocapsids (>1,000 nm [31]).

FIG 5.

Mutations in the YxxL motif of VP24 impaired intracellular transport of NCLSs. Huh-7 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding VP30-GFP, NP, VP35, and one of the VP24 constructs. Time-lapse images were captured from 20 h p.t. The pictures show the maximum intensity projection of time-lapse images of cells recorded for 3 min, and images were captured every 2 to 3 s. (B) The velocities of the NCLSs (n = 20). The mean and SD values are shown at the top of each graph. (C) The length of trajectories of the NCLSs (n = 20). The mean and SD values are shown at the top of each graph. The asterisks indicate statistical significance; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (D) The length of motile and immotile NCLSs was measured for each group (n = 50). The asterisks indicate statistical significance in comparison to VP24wt; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

The interaction between VP24 and Alix is mediated by the YxxL motif but plays no role in NCLS transport.

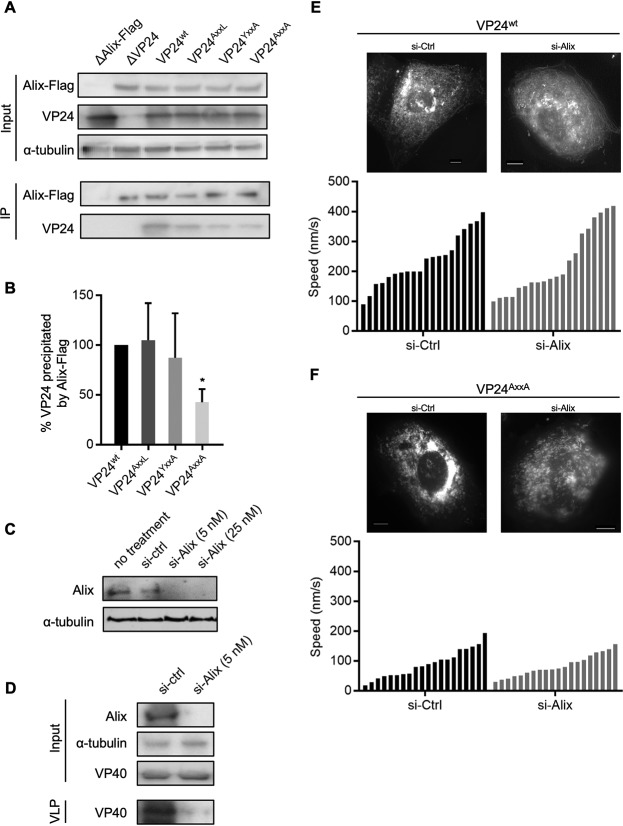

YxxL motifs are recognized by Alix, an ESCRT pathway interaction partner. Alix is a cytosolic protein in mammalian cells that can regulate seemingly disparate mechanisms (50). Besides its involvement in apoptotic signaling (51) and endocytic membrane trafficking (52, 53), Alix is also involved in cytoskeletal remodeling (54–56). It was therefore interesting to analyze whether an interaction between Alix and the YxxL motif of EBOV VP24 played a functional role in linking nucleocapsids and the cytoskeleton. We first performed coimmunoprecipitation assays with Alix and either VP24wt or each of the VP24 mutants, as previously described (57). The amount of VP24AxxA that was coprecipitated with Alix was reduced to 43% in comparison to VP24wt, suggesting that the YxxL motif is important for the interaction between VP24 and Alix (Fig. 6A and B).

FIG 6.

Analysis of the interaction between VP24 and Alix and live-cell imaging study of NCLS transport in Alix-knockdown cells. (A and B) Coimmunoprecipitation analysis of Flag-tagged Alix with each VP24 construct. HEK293 cells transiently expressing Flag-tagged Alix and one of the VP24 constructs were lysed at 48 h p.t., and protein complexes were precipitated using mouse anti-Flag M2 agarose. An aliquot of cell lysate (input) was collected before precipitation. (A) Western blot analysis was performed using Flag-, VP24-, and alpha-tubulin-specific antibodies. (B) The quantification of three independent experiments is shown in the graphs. The immunoprecipitated amount of VP24wt was set to 100%. The mean and SD values of the results from three independent experiments are shown. The asterisk indicates statistical significance; *, P < 0.05. (C) Treatment of Huh-7 cells with siRNA targeting Alix (si-Alix) or nonspecific siRNA (si-Ctrl) was applied, and cell lysates were collected at 48 h p.t. Western blot analysis was performed using Alix- and alpha-tubulin-specific antibodies. (D) Functional control of siRNA-mediated downregulation of Alix. Huh-7 cells were transfected with 500 ng of pCAGGS-VP40. One day prior to transfection, cells were treated with si-Alix or si-Ctrl. Cell lysates and VP40-induced VLPs were collected at 48 h p.t. Western blot analysis was performed using Alix-, VP40-, and alpha-tubulin-specific antibodies. (E and F) Live-cell imaging analysis of NCLS transport in Huh-7 cells, which were pretreated with si-Alix or si-Ctrl 1 day prior to transfection. These cells were transfected either with plasmids encoding VP30-GFP, NP, VP35, and VP24wt (E) or plasmids encoding VP30-GFP, NP, VP35, and VP24AxxA (F). Time-lapse images were captured from 20 h p.t. The pictures show the maximum intensity projection of time-lapse images recorded for 2 min, and images were captured every 1 s. The graphics show the velocities of the NCLSs (n = 20). Mean and SD are shown as numbers.

Since Alix is involved in cytoskeletal remodeling (54–56), it was interesting to analyze whether the impaired NCLS transport in the presence of the VP24 mutants was caused by impaired binding to Alix. We therefore downregulated the expression of Alix by a small interfering RNA (siRNA) approach, as confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 6C), and demonstrated a functional influence of Alix knockdown by the loss of VP40-induced budding of VLPs (Fig. 6D) (58). We then analyzed intracellular transport of NCLSs in Alix knockdown cells that were transfected with plasmids encoding NP, VP35, VP30-GFP, and one of the VP24 constructs. Live-cell imaging analysis demonstrated comparable velocities of NCLSs formed in the presence of VP24wt in si-Ctrl- and si-Alix-treated cells (236 ± 85 nm/s and 226 ± 111 nm/s, respectively) (Fig. 6E and Movies S5 and S6). Thus, it is suggested that Alix is not a major factor supporting the transport of NCLSs. The mean velocities of NCLSs formed by VP24AxxA also showed no difference in the si-Ctrl- and si-Alix-treated cells (89 ± 47 nm/s and 83 ± 36 nm/s, respectively) (Fig. 6F and Movies S7 and S8). Thus, the defective transport of VP24AxxA-containing NCLSs is caused by the impaired interaction with a so-far-unknown cellular protein. Further identification of cellular proteins that provide efficient NCLS transport via interaction with the VP24 YxxL motif in VP24 is dependent on reliable methods to purify motile NCLSs, which are currently not available.

Rescue attempts of recombinant EBOV encoding mutant VP24 failed.

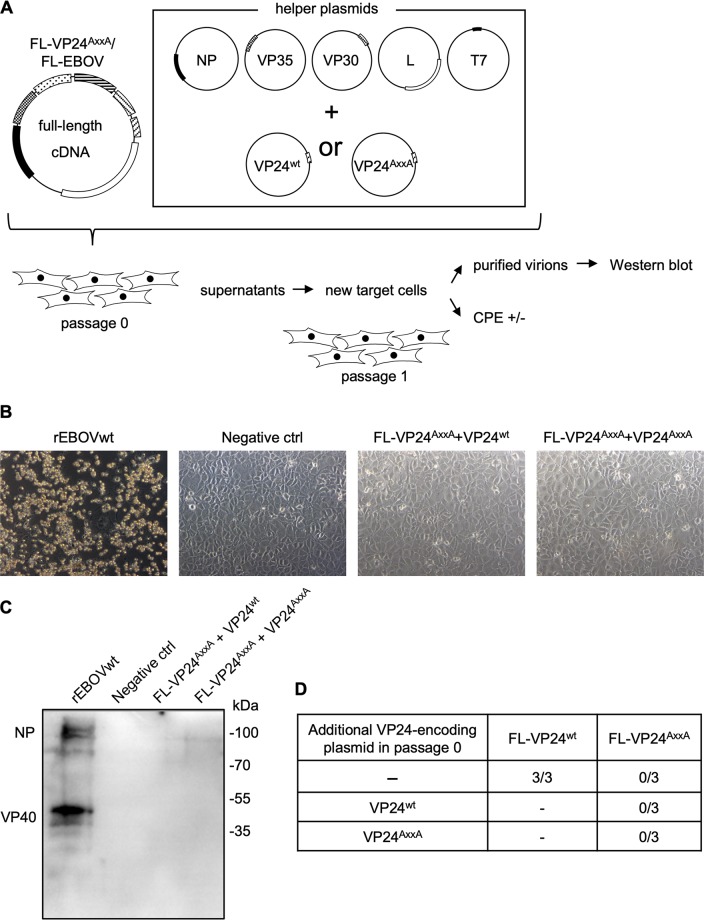

To reveal whether the mutation of the YxxL motif affects the rescue of recombinant EBOV, we constructed a full-length EBOV genome encoding VP24AxxA instead of VP24wt (FL-VP24AxxA) and tried to rescue recombinant mutant EBOV (Fig. 7A) (59–61). In separate approaches, plasmids encoding either VP24wt or VP24AxxA were cotransfected together with the other helper plasmids encoding NP, L, VP35, and VP30 with the aim of providing the function of VP24 in passage 0 cells. At day 7 p.t., the cell supernatants were harvested, and a blind passage was performed in fresh cells (passage 1). Only the positive control (full-length EBOV genome encoding VP24wt) exhibited clear cytopathic effect (CPE) in infected cells (Fig. 7B) and EBOV-specific protein bands in Western blotting (Fig. 7C). Cells transfected with plasmids encoding FL-VP24AxxA, NP, L, VP35, and VP30, as well as with either VP24wt or VP24AxxA as a helper plasmid, did not show any CPE or EBOV-specific protein bands in Western blotting (Fig. 7B and C). These experiments were performed in triplicates (Fig. 7D).

FIG 7.

Rescue of recombinant EBOV encoding double mutations in the YxxL motif of VP24. (A) Schematic representation of the procedure for full-length recombinant EBOV rescue experiments. Huh-7 cells were transfected with a full-length EBOV cDNA clone encoding VP24wt or VP24AxxA (FL-VP24AxxA). The helper plasmids encoding NP, VP35, VP30, L, T7 polymerase, and, optionally, either VP24wt or VP24AxxA were transfected as well (passage 0). At 7 days p.t., the cell supernatants were collected and applied to fresh cells (passage 1). The cytopathic effect was monitored up to 7 days p.i., and the cell supernatants were collected. (B) Light microscopy of passage 1 cells at day 7 p.i. (C) Western blot analysis of purified particles. The cell supernatants were collected at 7 days p.i. in passage 1 cells and subjected to ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-EBOV serum. (D) Summarized results of three individual rescue experiments with a full-length EBOV cDNA clone encoding VP24wt or VP24AxxA. Additionally applied VP24 plasmids are indicated in the left column. FL-wt, full-length EBOV genome encoding VP24wt; FL-AxxA, full-length EBOV genome encoding VP24AxxA. The number of successful rescue experiments and total number of performed rescue experiments are indicated.

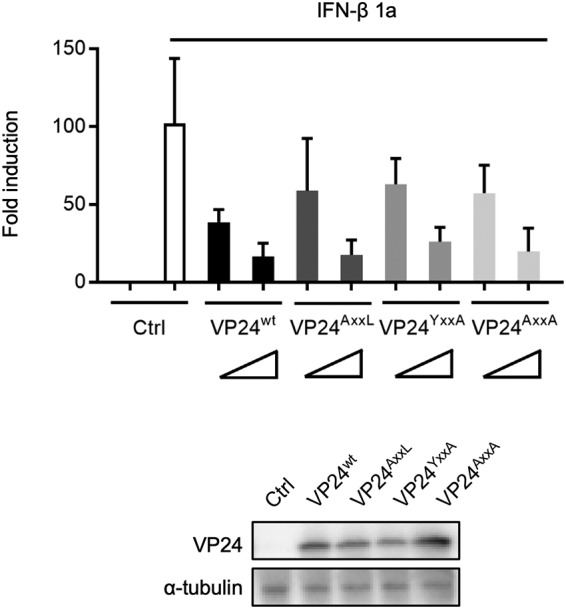

Mutations of the VP24 YxxL motif did not influence VP24’s IFN-antagonistic function.

Since a full-length EBOV genome encoding VP24AxxA could not be rescued and VP24 is known to interfere with the activation of innate immune responses (33–39), it was important to clarify whether the mutations in the YxxL motif influenced VP24’s interferon (IFN)-antagonistic functions. Here, we transfected cells with increasing amounts of plasmids encoding each VP24 construct and a plasmid encoding luciferase under the control of an IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) promoter (62). Twenty-four hours p.t., cell supernatants were replaced with medium containing human IFN-β1a. After incubation for a further 8 h, cells were lysed and the reporter activities measured. The expression of VP24 mutants inhibited the IFN-induced activation of the ISRE controlling reporter to a similar level as with VP24wt (Fig. 8), indicating that mutation of the YxxL motif in VP24 did not impair the IFN-antagonistic function.

FIG 8.

Influence of mutations in YxxL motif of VP24 on its IFN-antagonistic function. HEK293 cells were transfected with increasing amounts of plasmids (10 or 100 ng) encoding one of the VP24 constructs or an empty vector (control) and a luciferase-reporter plasmid under the control of an ISRE. Twenty-four hours later, the cell medium was replaced with either fresh medium (unstimulated) or medium containing 1,000 IU human IFN-β1a (stimulated). After a further 8 h, cells were lysed, and the reporter activity was measured. Fold induction was calculated as the ratio of reporter activities in stimulated to unstimulated cells. The mean and SD values of the results from three independent experiments are shown. Protein expression of VP24 (upon transfection with 100 ng of plasmids) and alpha-tubulin was analyzed by Western blotting.

DISCUSSION

Although mounting evidence indicates EBOV VP24 to be a crucial protein for the assembly and transport of viral nucleocapsids (29, 30, 32, 41), modulation of viral RNA synthesis (24, 28), and inhibition of interferon signaling (33–39), the amino acid motifs of VP24 which mediate these functions remain largely unexplored. Here, we present data showing that the YxxL motif at positions 172 to 175 in VP24 plays important roles in two processes during the EBOV life cycle. The integrity of the YxxL motif of VP24 was essential for the regulatory function of VP24 in viral RNA synthesis and for efficient transport of NCLSs, particularly the transport of long NCLSs. The latter result is of great importance, considering that the formation of infectious particles is achieved only if the long authentic EBOV nucleocapsids can be transported. Consequently, mutations in the YxxL motif of VP24 prevented the rescue of recombinant EBOV, highlighting the critical role of this motif in the virus life cycle. While the integrity of the YxxL motif supported the interaction with Alix, downregulation of Alix with siRNAs did not impair the intracellular transport of NCLSs. This result suggested that the YxxL motif in VP24 does not function to coopt the ESCRT machinery. In addition, mutation of the YxxL motif did not affect the VP24-mediated inhibition of IFN signaling.

Regulation of viral transcription and replication prior to budding is usually considered to be a function of mononegaviral matrix proteins (28, 63–66). Among EBOV nucleocapsid proteins, only VP24 is known to downregulate EBOV-specific minigenome transcription/replication, but the mechanism of action remains unclear (24). A current hypothesis suggests that the interaction between VP24 and NP induces nucleocapsid condensation and thus prevents further use of the nucleocapsid as a template for transcription and replication (24, 25, 28, 43). Our results indicate that substitution of the tyrosine at position 172 and/or leucine at position 175 of YxxL motif in VP24 affected neither the interaction between VP24 and NP nor the condensation of the helical nucleocapsid (Fig. 2B to D). Nevertheless, these mutations impaired VP24’s regulatory effect on minigenome-based transcription and replication (Fig. 2A and 4A), indicating that the modification of the YxxL motif influenced the template function of the nucleocapsid without affecting its condensation (Fig. 2D).

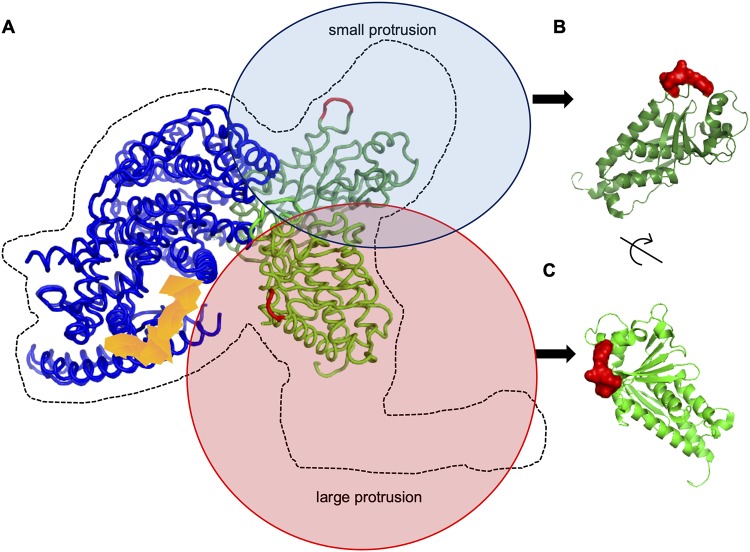

A recent cryo-electron microscopy study of EBOV nucleocapsids identified two VP24 molecules immediately adjacent to NP; one VP24 molecule is located in the small protrusion and one in the large protrusion of the nucleocapsid subunits composed of NP, VP24, and VP35 (32) (Fig. 9A). Remarkably, the orientations of the two VP24 molecules in the nucleocapsid subunit differ (32). The YxxL motif is located at one of the VP24 pyramid faces (Fig. 9, marked in red). In the VP24 molecule associated with the small protrusion of the nucleocapsid subunit, the YxxL motif is directed away from the subunit, possibly available for a cellular interaction partner(s) (Fig. 9B). The YxxL motif of the second VP24 molecule associated with the large protrusion of the nucleocapsid subunit is directed toward the putative RNA encapsidation cleft (Fig. 9C), where the YxxL motif might influence access to the viral RNA (marked in orange). Thus, it is possible that mutation of the YxxL motif in the two differently oriented VP24 molecules simultaneously impacts two or more functions of VP24. It is tempting to speculate that the transport efficiency of NCLSs is mediated by the YxxL motif which is facing the outside of NCLSs, at the interface between viral and cellular proteins. A more detailed analysis of the molecular mechanisms of how the YxxL motif in VP24 regulates viral RNA synthesis is necessary. However, this requires a better model of the nucleocapsid subunits, including the positions of polymerase L and VP30, which are currently not available.

FIG 9.

Localization of the YxxL motif in VP24 within the NCLS structure. (A) The location of the VP24 YxxL motif in the subtomogram averaging structure of the EBOV nucleocapsid subunit (PDB identifier [ID] 6EHM) reported by Wan et al. (32). The suggested nucleoprotein is shown in blue. The putative RNA encapsidation site is highlighted in orange. The locations of the YxxL motifs in the two VP24 molecules (in deep and light green) associated with the nucleocapsid subunit are indicated in red. (B and C) The YxxL motif location in the V24 molecule structure (PDB ID 4M0Q). (B) The YxxL motif (in red) located at the tip of a small protrusion-like structure. (C) The YxxL motif (in red) located in the large protrusion.

Mutations of the YxxL motif in VP24 did not affect the incorporation of viral proteins but caused an increased number of minigenomes in released trVLPs (Fig. 3B to E and 4B). This result suggested that relieving the inhibitory effect of VP24 on RNA synthesis increases the amount of available replicated minigenomes that can be incorporated into trVLPs. As reported previously, preparations of filoviral VLPs contain relatively small amounts of infectious particles; however, the reason remained unknown (47). The present study indicated that the number of minigenomes in P0 cells determined the infectivity of trVLPs (Fig. 4A and B).

To analyze the functional relevance of the YxxL motif in VP24 in the context of the viral life cycle, we tried to rescue a recombinant EBOV encoding VP24AxxA, which was unsuccessful (Fig. 7). Since VP24AxxA demonstrated a similar capacity to interfere with IFN signaling as VP24wt (Fig. 8), it is unlikely that an increased synthesis of interferon-stimulated genes prevented the formation of the mutant EBOV. This is supported by the finding that the inhibition of IFN signaling by EBOV VP24 involves three clusters of amino acids at positions 130 to 140, 184 to 186, and 201 to 207, which mediate its interaction with the nuclear transporter karyopherin alpha but not the YxxL motif (39). In contrast to EBOV VP24, the closely related MARV VP24 lacks the ability to modulate viral RNA synthesis. This function is carried out by MARV VP40 (67). A mutant of MARV VP40, VP40D184N, similar to VP24AxxA, showed a decreased suppressive effect on viral transcription/replication. Interestingly, recombinant MARV encoding VP40D184N was rescuable, suggesting that the impaired suppression of RNA synthesis by VP24AxxA is not critical for viral rescue (68). It is therefore assumed that the mutation’s impact on the transport of NCLSs, i.e., their short trajectories, reduced speed, and impaired capability of longer NCLS to be transported, are important factors that inhibited the rescue of recombinant EBOV FL-VP24AxxA. The EBOV nucleocapsids are >1,000 nm in length and therefore their transport is most likely not efficiently supported by the VP24AxxA mutant. Since the length restriction did not apply for the short NCLSs formed in the presence of EBOV minigenomes, their release was not significantly reduced.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the YxxL motif in EBOV VP24 plays a critical role in the VP24-mediated regulation of viral RNA transcription/replication and the movement particular to long NCLSs. Since the integrity of the YxxL motif is essential for the growth of EBOV, this motif might represent a potential target for antiviral interference.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Huh-7 (human hepatoma) and HEK293 (human embryonic kidney) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS; PAN Biotech), 5 mM l-glutamine (Q; Life Technologies), 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (PS; Life Technologies) and grown at 37°C with 5% CO2.

cDNA plasmids.

All plasmids coding for wild-type EBOV proteins (pCAGGS-NP, pCAGGS-VP35, pCAGGS-VP30, pCAGGS-L, pCAGGS-VP24, pCAGGS-VP40, and pCAGGS-GP), the EBOV-specific minigenome (3E5E-luc), and pCAGGS-T7 polymerase have been described earlier (46, 69). Cloning of pCAGGS-VP24AxxL, pCAGGS-VP24YxxA, and pCAGGS-VP24AxxA was performed using the multisite directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The Flag-tagged human Alix-coding plasmid pCAGGS-Alix-Flag was kindly provided by C. Chatellard-Cause.

Coimmunoprecipitation analysis.

A coimmunoprecipitation assay was carried out as previously described (57), with minor modifications. A six-well plate of HEK293 cells was transfected with 500 ng/well of each protein-encoding plasmid using the TransIT (Mirus) reagent. After 48 h, cells were lysed with 500 μl of ice-cold coimmunoprecipitation lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 17.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, with cOmplete protease inhibitor mixture [Roche]) for 20 min at room temperature and then subjected to sonication for 3 × 20 s at 4°C (Branson Sonifier 450). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10 min at 8,000 × g and 4°C). An aliquot of the clarified cell lysates was taken for expression control (input). The clarified cell lysates were added to 45 μl of equilibrated mouse anti-Flag M2 affinity gel agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated overnight at 4°C on the rotator. Precipitated protein complexes were washed three times with coimmunoprecipitation buffer without Triton X-100 via centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 3 min. Elution was achieved with 60 μl of elution buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, 2% SDS [pH 6.8]) for 5 min at room temperature, followed by 3 min at 95°C. The supernatants were centrifuged two times (14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C) in order to remove agarose beads completely. As for SDS-PAGE, the eluate was mixed 20 μl of loading buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl [pH 6.8]–0.2% bromophenol blue–20% glycerol–10% 2-mercaptoethanol–4% SDS) and subjected to gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis.

Antibodies.

For immunofluorescence analysis, a rabbit anti-VP24 antibody (kind gift from Viktor Volchkov) was used as a primary antibody, and goat anti-rabbit-Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (Invitrogen) was employed as a secondary antibody. The following primary antibodies were used for Western blot analysis: a chicken anti-NP polyclonal antibody (69), a mouse monoclonal VP35 antibody (6C5; Kerafast), a monoclonal mouse anti-VP40 (70), a rabbit anti-VP24 antibody (see above), a rabbit anti-ALIX antibody (Abcam), a mouse anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and a mouse anti-alpha-tubulin antibody (Abcam). The corresponding secondary antibodies were donkey anti-chicken-IRDye 680RD (Li-Cor), donkey anti-chicken-IRDye 800CW (Li-Cor), goat anti-rabbit-IRDye 680RD (Li-Cor), swine polyclonal anti-rabbit immunoglobulins/horseradish peroxidase (immunoglobulins/HRP; Dako), donkey anti-rabbit IRDye 800CW (Li-Cor), donkey anti-mouse 680RD (Li-Cor), and goat anti-mouse-IRDye 800CW (Li-Cor).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses were performed as described previously (57, 71). The blots were analyzed using the Image Lab software for HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies or Li-Cor Odyssey imaging system for fluorescently conjugated secondary antibodies, as indicated in “Antibodies,” above. The intensity of obtained bands was analyzed using the Fiji software (72).

Minigenome and trVLP reporter assay.

A minigenome assay was performed as described previously (28). Briefly, the plasmids for the minigenome assay (125 ng of pCAGGS-NP, 125 ng of pCAGGS-VP35, 100 ng of pCAGGS-VP30, 1,000 ng of pCAGGS-L, 250 ng of a EBOV-specific minigenome encoding the Renilla luciferase reporter gene, 250 ng of pCAGGS-T7 polymerase, and 100 ng of pCAGGS vector coding firefly luciferase reporter gene for normalization) with or without 100 ng of pCAGGS-VP24 constructs were transfected in HEK293 cells. Reporter activity was measured at 48 h p.t. The EBOV transcription- and replication-competent virus-like particle (trVLP) assay was performed as described earlier (46, 73), with minor modifications. Briefly, HEK293 cells were seeded in a six-well plate. Each well was transfected with plasmids encoding all EBOV structural proteins (125 ng of pCAGGS-NP, 125 ng of pCAGGS-VP35, 250 ng of pCAGGS-VP40, 250 ng of pCAGGS-GP, 100 ng of pCAGGS-VP30, 100 ng of pCAGGS-VP24, and 1,000 ng of pCAGGS-L), 250 ng of an EBOV-specific minigenome, 250 ng of pCAGGS-T7 polymerase, and 100 ng of pCAGGS vector encoding firefly luciferase for normalization. Culture supernatants of the three wells were collected at 72 h p.t., and released trVLPs were purified via ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion. The producer cells were lysed at 72 h p.t., and indicator cells infected with the purified trVLPs were lysed at 48 h postinfection (p.i.); subsequently, cell lysates were subjected to luciferase reporter assays (pjk, Germany).

Extraction of minigenome RNA from trVLPs for quantitative real-time PCR assay.

Producer cells (HEK293) were transfected with the components of an EBOV-specific trVLP assay components (see above), and culture supernatants were collected at 72 h p.t. The trVLPs were purified via ultracentrifugation through a 20% sucrose cushion and dissolved in RNase-free water. Total RNA was extracted using the QIAamp viral RNA minikit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and RNA was eluted in 50 μl of RNase-free water. The eluted RNA solutions were treated with an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen) to avoid DNA contamination. Ten-microliter aliquots of RNA solutions were used for reverse transcription of negative-strand RNA (viral RNA [vRNA]) using the Omniscript reverse transcription (RT) kit (Qiagen) in the presence of 10 U RiboLock RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific Fermentas), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The specific primer for reverse transcription of vRNA was luc(+) (5′-GGC CTC TTC TTA TTT ATG GCG A-3′) (28). The acquired cDNA solution was diluted 5 times. Subsequently, quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using the QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit with 5 μl of cDNA as the template and both the luc(−) (5′-AGA ACC ATT ACC AGA TTT GCC TGA-3′) and luc(+) primers, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Minigenome plasmid DNA was used to standardize the genome copy numbers (28).

Immunofluorescence confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis.

Immunofluorescence confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis was performed as described previously (20, 74). The microscopic images were acquired by a Leica SP5 confocal laser scanning microscope using a 63× oil objective (Leica Microsystems). Cells were grown on glass coverslips and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 24 to 48 h p.t. Optionally, nuclear staining was achieved by using DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2′-phenylindole) (41).

Live-cell microscopy.

For live-cell imaging, Huh-7 cells were seeded onto 4-well (2 × 104 cells)/8-well (1 × 104 cells) μ-Slide (ibidi) and cultivated in DMEM-PS-Q with 10% FBS. The transfection was performed in 50 μl Opti-MEM without phenol red (Life Technologies) (75, 76). The inoculum was removed at 1 h p.t., and a volume of 250 μl of CO2-independent Leibovitz’s medium was added (Life Technologies). Live-cell time-lapse experiments were recorded with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E microscope using a 63× oil objective. Pictures and movie sequences were processed using the Nikon NIS Elements 4.1 software (41).

Electron microscopy.

The purified trVLPs were negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid. Cellular specimens were analyzed as indicated below. Huh-7 cells transfected with plasmids encoding NP, VP35, and one of the VP24 constructs were fixed with aldehydes, postfixed with 1 % osmium tetraoxide, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in a mixture of Epon and Araldite. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The electron micrographs of negatively stained samples and ultrathin sections were acquired using a JEM1400 with a TVIPS TemCam F416 camera (77).

Analysis of VLP number and length by transmission electron microscopy.

Counting of VLPs was performed as described previously (78). Briefly, trVLPs purified through a 20% sucrose cushion were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and combined with an equal volume of polystyrene beads of a known concentration (137 nm in diameter; Plano, Germany). The trVLP-bead mixtures were centrifuged directly onto Formvar-coated, 400-mesh nickel grids pretreated with 1% alcian blue using a Beckman Coulter Airfuge. Then, grids were negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid. The VLPs and beads were counted in 10 different randomly chosen squares using a JEM 1400 transmission electron microscope. The total number of virus particles per milliliter was determined according to the following equation: (mean number of virus particles per square) × (concentration of latex beads)/(mean number of latex beads per square). The values obtained for VP24wt-induced trVLPs were set to 100%. The length of >100 trVLPs was measured for each of the VP24wt- or VP24 mutant-induced trVLPs in three independent preparations of trVLPs. The percentage of trVLPs with length ranging from 200 to 500 nm or of more than 500 nm was calculated for each of the trVLP preparations.

siRNA.

Human Alix-specific or control siRNAs were purchased from Qiagen. Six-well plates or 4-well/8-well ibidi dishes of Huh-7 cells were transfected with either control or Alix-specific siRNAs at a final concentration of 5 nM using HiPerFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) 1 day prior to transfection of plasmids encoding viral proteins. To confirm the effect of siRNA treatment, the protein levels of Alix were determined by Western blotting.

Rescue of recombinant EBOV.

The recombinant Ebola virus (rEBOVwt) used in this study was based on EBOV Zaire (strain Mayinga; GenBank accession number AF272001). Cloning and rescue of full-length EBOV were performed as described earlier (59–61), with minor modifications. Briefly, 1,000 ng of each full-length wt or mutant EBOV cDNA clone (based on pAMP Zaire Ebola virus [ZEBOV], kindly provided by G. Neumann) together with helper plasmids (125 ng of pCAGGS-NP, 125 ng of pCAGGS-VP35, 1,000 ng of pCAGGS-L, 100 ng of pCAGGS-VP30, 250 ng of pCAGGS-T7, and 100 ng of either pCAGGS-VP24wt or pCAGGS-VP24AxxA) were transfected to Huh-7 cells. The cell supernatants were transferred to fresh Huh-7 cells at 7 days p.t. These passage 1 cells were inspected to check for cytopathic effects. At day 7 p.i., the cell supernatants were collected, and released virions were purified by ultracentrifugation. The presence of EBOV proteins was examined by Western blot analyses. All work with recombinant EBOV was performed in the biosafety level 4 (BSL-4) facility at the Philipps-Universität Marburg.

IFN-β signaling inhibition assay.

HEK293 cells were seeded in 12-well plates 1 day prior to transfection. At the time of transfection, the cells showed approximately 50% confluence. The cells were transfected with 10 ng or 100 ng of plasmids encoding each VP24 construct or empty vector (control), 250 ng of pISRE reporter plasmid encoding firefly luciferase (Agilent), and 50 ng pCAGGS-hrluc for normalization (62). The total amount of transfected DNA was held constant by transfection with empty vector. Twenty-four hours later, the cell culture medium was replaced with either fresh medium (unstimulated) or medium containing 1,000 IU/well human IFN-β1a (PBL Assay Science) for stimulation of IFN-β signaling. After a further 8 h, cells were lysed, and the reporter activity was measured.

Statistical analysis.

The presented mean values and standard deviations are derived from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism. Normally distributed samples were analyzed by a t test. Statistically significant differences are indicated with asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Olga Dolnik and Thomas Strecker for fruitful discussions. We are grateful to Viktor E. Volchkov for providing EBOV anti-VP24 antibodies. The BSL-4 work would not have been possible without the supervision of Markus Eickmann and technical support from Michael Schmidt and Gotthard Ludwig.

This work was supported by overseas research fellowships of the Uehara Memorial Foundation and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) grants 18J01631 and 19K16666, Ichiro Kanahara Foundation grant 19KI268 (to Y.T.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; German Research Foundation) Projektnummer 197785619-SFB 1021 (to S.B.), the AMED Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases, the AMED Japanese Initiative for Progress of Research on Infectious Disease for Global Epidemic, JSPS Core-to-Core Program A, the Advanced Research Networks, a grant from the Joint Research Project of the Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo, the Joint Usage/Research Center Program of the Institute for Frontier Life and Medical Sciences, Kyoto University, the Daiichi Sankyo Foundation of Life Science, and the Takeda Science Foundation (to T.N.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amarasinghe GK, Aréchiga Ceballos NG, Banyard AC, Basler CF, Bavari S, Bennett AJ, Blasdell KR, Briese T, Bukreyev A, Caì Y, Calisher CH, Campos Lawson C, Chandran K, Chapman CA, Chiu CY, Choi K-S, Collins PL, Dietzgen RG, Dolja VV, Dolnik O, Domier LL, Dürrwald R, Dye JM, Easton AJ, Ebihara H, Echevarría JE, Fooks AR, Formenty PBH, Fouchier RAM, Freuling CM, Ghedin E, Goldberg TL, Hewson R, Horie M, Hyndman TH, Jiāng D, Kityo R, Kobinger GP, Kondō H, Koonin EV, Krupovic M, Kurath G, Lamb RA, Lee B, Leroy EM, Maes P, Maisner A, Marston DA, Mor SK, Müller T, et al. 2018. Taxonomy of the order Mononegavirales: update 2018. Arch Virol 163:2283–2294. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3814-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. 2019. Ebola virus disease: Democratic Republic of the Congo. External situation report 29. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/310928/SITREP_EVD_DRC_20190219-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed February 27, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davey RT Jr, Dodd L, Proschan M, Jahrling P, Hensley L, Higgs E, Lane HC. 2018. The past need not be prologue: recommendations for testing and positioning the most-promising medical countermeasures for the next outbreak of Ebola virus infection. J Infect Dis 218(Suppl 5):S690–S697. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keshtkar-Jahromi M, Martins KAO, Cardile AP, Reisler RB, Christopher GW, Bavari S. 2018. Treatment-focused Ebola trials, supportive care and future of filovirus care. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 16:67–76. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1413937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narahara C, Yasuda J. 2015. Roles of the three L-domains in beta-retrovirus budding. Microbiol Immunol 59:545–554. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obiang L, Raux H, Ouldali M, Blondel D, Gaudin Y. 2012. Phenotypes of vesicular stomatitis virus mutants with mutations in the PSAP motif of the matrix protein. J Gen Virol 93:857–865. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.039800-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottwein E, Bodem J, Muller B, Schmechel A, Zentgraf H, Krausslich HG. 2003. The Mason-Pfizer monkey virus PPPY and PSAP motifs both contribute to virus release. J Virol 77:9474–9485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.17.9474-9485.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honeychurch KM, Yang G, Jordan R, Hruby DE. 2007. The vaccinia virus F13L YPPL motif is required for efficient release of extracellular enveloped virus. J Virol 81:7310–7315. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolff S, Ebihara H, Groseth A. 2013. Arenavirus budding: a common pathway with mechanistic differences. Viruses 5:528–549. doi: 10.3390/v5020528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bieniasz PD. 2006. Late budding domains and host proteins in enveloped virus release. Virology 344:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freed EO. 2002. Viral late domains. J Virol 76:4679–4687. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.10.4679-4687.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urata S, Yasuda J. 2010. Regulation of Marburg virus (MARV) budding by Nedd4.1: a different WW domain of Nedd4.1 is critical for binding to MARV and Ebola virus VP40. J Gen Virol 91:228–234. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han Z, Lu J, Liu Y, Davis B, Lee MS, Olson MA, Ruthel G, Freedman BD, Schnell MJ, Wrobel JE, Reitz AB, Harty RN. 2014. Small-molecule probes targeting the viral PPxY-host Nedd4 interface block egress of a broad range of RNA viruses. J Virol 88:7294–7306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00591-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han Z, Sagum CA, Bedford MT, Sidhu SS, Sudol M, Harty RN. 2016. ITCH E3 ubiquitin ligase interacts with Ebola virus VP40 to regulate budding. J Virol 90:9163–9171. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01078-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han Z, Sagum CA, Takizawa F, Ruthel G, Berry CT, Kong J, Sunyer JO, Freedman BD, Bedford MT, Sidhu SS, Sudol M, Harty RN. 2017. Ubiquitin ligase WWP1 interacts with Ebola virus VP40 to regulate egress. J Virol 91:e00812-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00812-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goff A, Ehrlich LS, Cohen SN, Carter CA. 2003. Tsg101 control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag trafficking and release. J Virol 77:9173–9182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.17.9173-9182.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irie T, Shimazu Y, Yoshida T, Sakaguchi T. 2007. The YLDL sequence within Sendai virus M protein is critical for budding of virus-like particles and interacts with Alix/AIP1 independently of C protein. J Virol 81:2263–2273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02218-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groseth A, Wolff S, Strecker T, Hoenen T, Becker S. 2010. Efficient budding of the Tacaribe virus matrix protein z requires the nucleoprotein. J Virol 84:3603–3611. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02429-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strack B, Calistri A, Craig S, Popova E, Gottlinger HG. 2003. AIP1/ALIX is a binding partner for HIV-1 p6 and EIAV p9 functioning in virus budding. Cell 114:689–699. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00653-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolnik O, Kolesnikova L, Stevermann L, Becker S. 2010. Tsg101 is recruited by a late domain of the nucleocapsid protein to support budding of Marburg virus-like particles. J Virol 84:7847–7856. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00476-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shtanko O, Watanabe S, Jasenosky LD, Watanabe T, Kawaoka Y. 2011. ALIX/AIP1 is required for NP incorporation into Mopeia virus Z-induced virus-like particles. J Virol 85:3631–3641. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01984-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolnik O, Kolesnikova L, Welsch S, Strecker T, Schudt G, Becker S. 2014. Interaction with Tsg101 is necessary for the efficient transport and release of nucleocapsids in Marburg virus-infected cells. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004463. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrel M, Haag L, Nilsson J, Staeheli P, Schneider U. 2013. Reverse genetics identifies the product of open reading frame 4 as an essential particle assembly factor of Nyamanini virus. J Virol 87:8257–8260. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00163-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe S, Noda T, Halfmann P, Jasenosky L, Kawaoka Y. 2007. Ebola virus (EBOV) VP24 inhibits transcription and replication of the EBOV genome. J Infect Dis 196(Suppl 2):S284–S290. doi: 10.1086/520582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noda T, Halfmann P, Sagara H, Kawaoka Y. 2007. Regions in Ebola virus VP24 that are important for nucleocapsid formation. J Infect Dis 196(Suppl 2):S247–S250. doi: 10.1086/520596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elliott LH, Kiley MP, McCormick JB. 1985. Descriptive analysis of Ebola virus proteins. Virology 147:169–176. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han Z, Boshra H, Sunyer JO, Zwiers SH, Paragas J, Harty RN. 2003. Biochemical and functional characterization of the Ebola virus VP24 protein: implications for a role in virus assembly and budding. J Virol 77:1793–1800. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.3.1793-1800.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoenen T, Jung S, Herwig A, Groseth A, Becker S. 2010. Both matrix proteins of Ebola virus contribute to the regulation of viral genome replication and transcription. Virology 403:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang Y, Xu L, Sun Y, Nabel GJ. 2002. The assembly of Ebola virus nucleocapsid requires virion-associated proteins 35 and 24 and posttranslational modification of nucleoprotein. Mol Cell 10:307–316. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe S, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. 2006. Functional mapping of the nucleoprotein of Ebola virus. J Virol 80:3743–3751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3743-3751.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bharat TA, Noda T, Riches JD, Kraehling V, Kolesnikova L, Becker S, Kawaoka Y, Briggs JA. 2012. Structural dissection of Ebola virus and its assembly determinants using cryo-electron tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:4275–4280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120453109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan W, Kolesnikova L, Clarke M, Koehler A, Noda T, Becker S, Briggs J. 2017. Structure and assembly of the Ebola virus nucleocapsid. Nature 551:394–397. doi: 10.1038/nature24490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reid SP, Leung LW, Hartman AL, Martinez O, Shaw ML, Carbonnelle C, Volchkov VE, Nichol ST, Basler CF. 2006. Ebola virus VP24 binds karyopherin alpha1 and blocks STAT1 nuclear accumulation. J Virol 80:5156–5167. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02349-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang AP, Bornholdt ZA, Liu T, Abelson DM, Lee DE, Li S, Woods VL Jr, Saphire EO. 2012. The Ebola virus interferon antagonist VP24 directly binds STAT1 and has a novel, pyramidal fold. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002550. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He F, Melen K, Maljanen S, Lundberg R, Jiang M, Osterlund P, Kakkola L, Julkunen I. 2017. Ebolavirus protein VP24 interferes with innate immune responses by inhibiting interferon-lambda1 gene expression. Virology 509:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mateo M, Reid SP, Leung LW, Basler CF, Volchkov VE. 2010. Ebolavirus VP24 binding to karyopherins is required for inhibition of interferon signaling. J Virol 84:1169–1175. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01372-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu W, Edwards MR, Borek DM, Feagins AR, Mittal A, Alinger JB, Berry KN, Yen B, Hamilton J, Brett TJ, Pappu RV, Leung DW, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2014. Ebola virus VP24 targets a unique NLS binding site on karyopherin alpha 5 to selectively compete with nuclear import of phosphorylated STAT1. Cell Host Microbe 16:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reid SP, Valmas C, Martinez O, Sanchez FM, Basler CF. 2007. Ebola virus VP24 proteins inhibit the interaction of NPI-1 subfamily karyopherin alpha proteins with activated STAT1. J Virol 81:13469–13477. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01097-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwarz TM, Edwards MR, Diederichs A, Alinger JB, Leung DW, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. 2017. VP24-karyopherin alpha binding affinities differ between Ebolavirus species, influencing interferon inhibition and VP24 stability. J Virol 91:e01715-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01715-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mühlberger E, Weik M, Volchkov VE, Klenk HD, Becker S. 1999. Comparison of the transcription and replication strategies of Marburg virus and Ebola virus by using artificial replication systems. J Virol 73:2333–2342. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.3.2333-2342.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takamatsu Y, Kolesnikova L, Becker S. 2018. Ebola virus proteins NP, VP35, and VP24 are essential and sufficient to mediate nucleocapsid transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:1075–1080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712263115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watt A, Moukambi F, Banadyga L, Groseth A, Callison J, Herwig A, Ebihara H, Feldmann H, Hoenen T. 2014. A novel life cycle modeling system for Ebola virus shows a genome length-dependent role of VP24 in virus infectivity. J Virol 88:10511–10524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01272-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banadyga L, Hoenen T, Ambroggio X, Dunham E, Groseth A, Ebihara H. 2017. Ebola virus VP24 interacts with NP to facilitate nucleocapsid assembly and genome packaging. Sci Rep 7:7698. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08167-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mateo M, Carbonnelle C, Martinez MJ, Reynard O, Page A, Volchkova VA, Volchkov VE. 2011. Knockdown of Ebola virus VP24 impairs viral nucleocapsid assembly and prevents virus replication. J Infect Dis 204(Suppl 3):S892–S896. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Licata JM, Johnson RF, Han Z, Harty RN. 2004. Contribution of Ebola virus glycoprotein, nucleoprotein, and VP24 to budding of VP40 virus-like particles. J Virol 78:7344–7351. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7344-7351.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoenen T, Groseth A, Kolesnikova L, Theriault S, Ebihara H, Hartlieb B, Bamberg S, Feldmann H, Stroher U, Becker S. 2006. Infection of naive target cells with virus-like particles: implications for the function of Ebola virus VP24. J Virol 80:7260–7264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00051-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoenen T, Groseth A, de Kok-Mercado F, Kuhn JH, Wahl-Jensen V. 2011. Minigenomes, transcription and replication competent virus-like particles and beyond: reverse genetics systems for filoviruses and other negative stranded hemorrhagic fever viruses. Antiviral Res 91:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spiegelberg L, Wahl-Jensen V, Kolesnikova L, Feldmann H, Becker S, Hoenen T. 2011. Genus-specific recruitment of filovirus ribonucleoprotein complexes into budding particles. J Gen Virol 92:2900–2905. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.036863-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schudt G, Dolnik O, Kolesnikova L, Biedenkopf N, Herwig A, Becker S. 2015. Transport of Ebolavirus nucleocapsids is dependent on actin polymerization: live-cell imaging analysis of Ebolavirus-infected cells. J Infect Dis 212(Suppl 2):S160–S166. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Odorizzi G. 2006. The multiple personalities of Alix. J Cell Sci 119:3025–3032. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Missotten M, Nichols A, Rieger K, Sadoul R. 1999. Alix, a novel mouse protein undergoing calcium-dependent interaction with the apoptosis-linked-gene 2 (ALG-2) protein. Cell Death Differ 6:124–129. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katoh K, Shibata H, Suzuki H, Nara A, Ishidoh K, Kominami E, Yoshimori T, Maki M. 2003. The ALG-2-interacting protein Alix associates with CHMP4b, a human homologue of yeast Snf7 that is involved in multivesicular body sorting. J Biol Chem 278:39104–39113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katoh K, Shibata H, Hatta K, Maki M. 2004. CHMP4b is a major binding partner of the ALG-2-interacting protein Alix among the three CHMP4 isoforms. Arch Biochem Biophys 421:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bongiovanni A, Romancino DP, Campos Y, Paterniti G, Qiu X, Moshiach S, Di Felice V, Vergani N, Ustek D, d’Azzo A. 2012. Alix protein is substrate of Ozz-E3 ligase and modulates actin remodeling in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 287:12159–12171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.297036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campos Y, Qiu X, Gomero E, Wakefield R, Horner L, Brutkowski W, Han Y-G, Solecki D, Frase S, Bongiovanni A, d’Azzo A. 2016. Alix-mediated assembly of the actomyosin-tight junction polarity complex preserves epithelial polarity and epithelial barrier. Nat Commun 7:11876. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pan S, Wang R, Zhou X, He G, Koomen J, Kobayashi R, Sun L, Corvera J, Gallick GE, Kuang J. 2006. Involvement of the conserved adaptor protein Alix in actin cytoskeleton assembly. J Biol Chem 281:34640–34650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602263200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Biedenkopf N, Hartlieb B, Hoenen T, Becker S. 2013. Phosphorylation of Ebola virus VP30 influences the composition of the viral nucleocapsid complex: impact on viral transcription and replication. J Biol Chem 288:11165–11174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.461285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han Z, Madara JJ, Liu Y, Liu W, Ruthel G, Freedman BD, Harty RN. 2015. ALIX rescues budding of a double PTAP/PPEY L-domain deletion mutant of Ebola VP40: a role for ALIX in Ebola virus egress. J Infect Dis 212(Suppl 2):S138–S145. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krähling V, Dolnik O, Kolesnikova L, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Jordan I, Sandig V, Günther S, Becker S. 2010. Establishment of fruit bat cells (Rousettus aegyptiacus) as a model system for the investigation of filoviral infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 4:e802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoenen T, Shabman RS, Groseth A, Herwig A, Weber M, Schudt G, Dolnik O, Basler CF, Becker S, Feldmann H. 2012. Inclusion bodies are a site of ebolavirus replication. J Virol 86:11779–11788. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01525-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Groseth A, Marzi A, Hoenen T, Herwig A, Gardner D, Becker S, Ebihara H, Feldmann H. 2012. The Ebola virus glycoprotein contributes to but is not sufficient for virulence in vivo. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002847. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dunham EC, Banadyga L, Groseth A, Chiramel AI, Best SM, Ebihara H, Feldmann H, Hoenen T. 2015. Assessing the contribution of interferon antagonism to the virulence of West African Ebola viruses. Nat Commun 6:8000. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clinton GM, Burge BW, Huang AS. 1978. Effects of phosphorylation and pH on the association of NS protein with vesicular stomatitis virus cores. J Virol 27:340–346. doi: 10.1128/JVI.27.2.340-346.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Finke S, Mueller-Waldeck R, Conzelmann KK. 2003. Rabies virus matrix protein regulates the balance of virus transcription and replication. J Gen Virol 84:1613–1621. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iwasaki M, Takeda M, Shirogane Y, Nakatsu Y, Nakamura T, Yanagi Y. 2009. The matrix protein of measles virus regulates viral RNA synthesis and assembly by interacting with the nucleocapsid protein. J Virol 83:10374–10383. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01056-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ogino T, Iwama M, Ohsawa Y, Mizumoto K. 2003. Interaction of cellular tubulin with Sendai virus M protein regulates transcription of viral genome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 311:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Valmas C, Grosch MN, Schumann M, Olejnik J, Martinez O, Best SM, Krahling V, Basler CF, Muhlberger E. 2010. Marburg virus evades interferon responses by a mechanism distinct from Ebola virus. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000721. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koehler A, Kolesnikova L, Welzel U, Schudt G, Herwig A, Becker S. 2016. A single amino acid change in the Marburg virus matrix protein VP40 provides a replicative advantage in a species-specific manner. J Virol 90:1444–1454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02670-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Biedenkopf N, Lier C, Becker S. 2016. Dynamic phosphorylation of VP30 is essential for Ebola virus life cycle. J Virol 90:4914–4925. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03257-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoenen T, Volchkov V, Kolesnikova L, Mittler E, Timmins J, Ottmann M, Reynard O, Becker S, Weissenhorn W. 2005. VP40 octamers are essential for Ebola virus replication. J Virol 79:1898–1905. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1898-1905.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kolesnikova L, Bamberg S, Berghofer B, Becker S. 2004. The matrix protein of Marburg virus is transported to the plasma membrane along cellular membranes: exploiting the retrograde late endosomal pathway. J Virol 78:2382–2393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.78.5.2382-2393.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Biedenkopf N, Hoenen T. 2017. Modeling the Ebolavirus life cycle with transcription and replication-competent viruslike particle assays. Methods Mol Biol 1628:119–131. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7116-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kolesnikova L, Mittler E, Schudt G, Shams-Eldin H, Becker S. 2012. Phosphorylation of Marburg virus matrix protein VP40 triggers assembly of nucleocapsids with the viral envelope at the plasma membrane. Cell Microbiol 14:182–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takamatsu Y, Dolnik O, Noda T, Becker S. 2019. A live-cell imaging system for visualizing the transport of Marburg virus nucleocapsid-like structures. Virol J 16:159. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1267-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Takamatsu Y, Kajikawa J, Muramoto Y, Nakano M, Noda T. 2019. Microtubule-dependent transport of arenavirus matrix protein demonstrated using live-cell imaging microscopy. Microscopy (Oxf) 68:450–456. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfz034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dietzel E, Kolesnikova L, Sawatsky B, Heiner A, Weis M, Kobinger GP, Becker S, von Messling V, Maisner A. 2015. Nipah virus matrix protein influences fusogenicity and is essential for particle infectivity and stability. J Virol 90:2514–2522. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02920-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Alfson KJ, Avena LE, Beadles MW, Staples H, Nunneley JW, Ticer A, Dick EJ Jr, Owston MA, Reed C, Patterson JL, Carrion R Jr, Griffiths A. 2015. Particle-to-PFU ratio of Ebola virus influences disease course and survival in cynomolgus macaques. J Virol 89:6773–6781. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00649-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.