Since the discovery of murine polyomavirus in the 1950s, polyomaviruses (PyVs) have been considered highly host restricted in mammals. Sympatric bat communities commonly contain several different bat species in an ecological niche facilitating viral transmission, and they therefore represent a model to identify host-switching events of PyVs. In this study, we screened PyVs in a large number of bats in sympatric communities from diverse habitats across China. We provide evidence that cross-species bat-borne PyV transmission exists, though is limited, and that host-switching events appear relatively rare during the evolutionary history of these viruses. PyVs with close genomic identities were also identified in different bat species without host-switching events. Based on these findings, we propose an evolutionary scheme for bat-borne PyVs in which limited host-switching events occur on the background of codivergence and lineage duplication, generating the viral genetic diversity in bats.

KEYWORDS: bats, polyomavirus, host switching, codivergence

ABSTRACT

Polyomaviruses (PyVs) are small DNA viruses carried by diverse vertebrates. The evolutionary relationships of viruses and hosts remain largely unclear due to very limited surveillance in sympatric communities. In order to investigate whether PyVs can transmit among different mammalian species and to identify host-switching events in the field, we conducted a systematic study of a large collection of bats (n = 1,083) from 29 sympatric communities across China which contained multiple species with frequent contact. PyVs were detected in 21 bat communities, with 192 PyVs identified in 186 bats from 15 species within 6 families representing at least 28 newly described PyVs. Surveillance results and phylogenetic analyses surprisingly revealed three interfamily PyV host-switching events in these sympatric bat communities: two distinct PyVs were identified in two bat species in restricted geographical locations, while another PyV clustered phylogenetically with PyVs carried by bats from a different host family. Virus-host relationships of all discovered PyVs were also evaluated, and no additional host-switching events were found. PyVs were identified in different horseshoe bat species in sympatric communities without observation of host-switching events, showed high genomic identities, and clustered with each other. This suggested that even for PyVs with high genomic identities in closely related host species, the potential for host switching is low. In summary, our findings revealed that PyV host switching in sympatric bat communities can occur but is limited and that host switching of bat-borne PyVs is relatively rare on the predominantly evolutionary background of codivergence with their hosts.

IMPORTANCE Since the discovery of murine polyomavirus in the 1950s, polyomaviruses (PyVs) have been considered highly host restricted in mammals. Sympatric bat communities commonly contain several different bat species in an ecological niche facilitating viral transmission, and they therefore represent a model to identify host-switching events of PyVs. In this study, we screened PyVs in a large number of bats in sympatric communities from diverse habitats across China. We provide evidence that cross-species bat-borne PyV transmission exists, though is limited, and that host-switching events appear relatively rare during the evolutionary history of these viruses. PyVs with close genomic identities were also identified in different bat species without host-switching events. Based on these findings, we propose an evolutionary scheme for bat-borne PyVs in which limited host-switching events occur on the background of codivergence and lineage duplication, generating the viral genetic diversity in bats.

INTRODUCTION

Polyomaviruses (PyVs) are nonenveloped icosahedral DNA viruses containing a circular and highly stable double-stranded DNA genome (1–3). PyVs can induce neoplastic transformation in cell culture (2) and are associated with malignancy in humans (4, 5) and raccoons (6). PyVs are considered highly host specific in different mammalian species, and long-range host jumps leading to productive infection and transmission within mammalian genera are rare or nonexistent (7, 8). Moreover, only one previous report on PyVs in African insectivorous and frugivorous bats has revealed evidence for short-range host-switching events of PyVs in horseshoe bats (family Rhinolophidae, genus Rhinolophus) following identification of nearly identical viruses (99.9% at the genomic level) in Rhinolophus blasii and Rhinolophus simulator (9). The extent of the diversity of PyVs is largely unknown, and the host spectrum of PyVs has rarely been investigated systematically in mammals in their natural habitats; therefore, it is unclear whether these agents could transmit among different mammalian species in natural environmental conditions or represent potential zoonotic threats for human or domesticated animals.

Currently, 98 species carried by various mammals, birds, and fish are recognized within the family Polyomaviridae by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) and classified into four separate genera (Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-, and Deltapolyomavirus), with 9 recognized species still to be classified (10). Recent identification of diverse PyV-like sequences in different fish species (8) and invertebrates (including arachnids and insects) has revealed a deep coevolutionary history of PyVs with their metazoan hosts (8); furthermore, an intrahost codivergence model with lineage duplication events at evolutionary timescales has been proposed to explain the extant diversity based on the available genetic data (8).

Bats (order Chiroptera) account for more than 20% of mammalian species, with >1,100 known species in >200 genera worldwide (11). Prior investigations with bats have revealed a rich diversity of PyVs among bat species and even multiple PyV infecting the same bat host (3, 9, 12). So far, 15 alphapolyomaviruses and 10 betapolyomaviruses have been formally recognized in insectivorous and frugivorous bat species within the Americas, Africa, Southeast Asia (Indonesia), and the Pacific (New Zealand) (9, 12–18). These studies identified significant diversity and high positivity rates (10 to 20 %) using molecular approaches (19). PyVs with complete or partial genomes have also been identified by metagenomic analyses with bats collected in China and recently from Saudi Arabia (20–22). Therefore, sympatric bat communities, commonly containing several different bat species, are an ecological niche that facilitates viral transmission and represent an ideal model to identify the extent of viral genetic diversity and the transmission potential of virus infections in different bat families.

The present study investigated the PyV diversity and potential for transmission in diverse bat species living in sympatric communities in five Chinese provincial regions. A significant number of previously uncharacterized PyVs were discovered from a large number of insectivorous and frugivorous bat samples collected in diverse ecological environments. Virus-host relationships for all newly discovered PyVs were evaluated, and these analyses revealed that PyV cross-transmission in sympatric bat communities exists, though it is rare, and host-switching events of bat-borne PyVs were characterized in the background of codivergence with lineage duplication events.

RESULTS

Detection of polyomaviruses in Chinese bats.

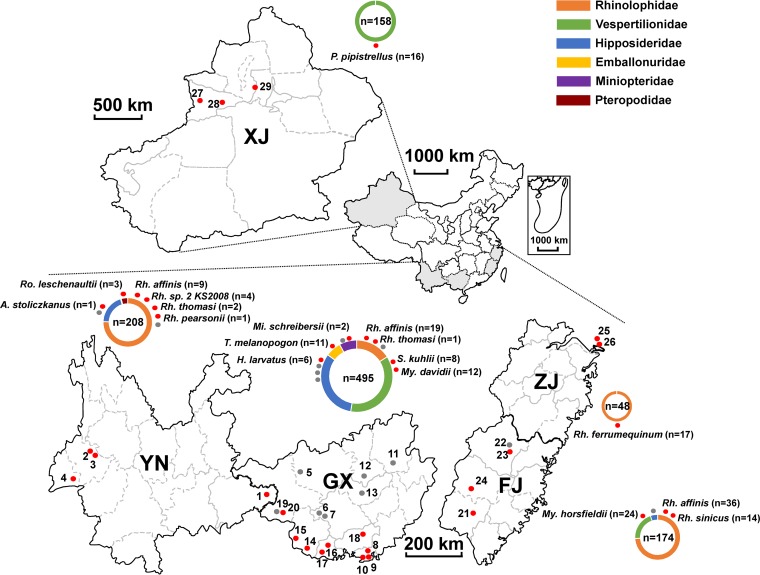

In 2015-2016, a total of 1,083 bats belonging to 20 species in 6 families (Rhinolophidae, Vespertilionidae, Hipposideridae, Emballonuridae, Miniopteridae, and Pteropodidae) were collected from 29 different communities (communities 1 to 29 in Fig. 1 and Table S1 in the supplemental material) from five provincial regions in southwest (Yunnan and Guangxi), southeast (Fujian and Zhejiang), and northwest (Xinjiang) of China. The bats were identified morphologically by field-trained experts during sampling and confirmed by partial sequencing of the mitochondrial cytochrome b genes (cytb) (23) of representative individuals in every community (Table S1). The bats were insectivorous except for one fruit bat species, Rousettus leschenaultii in the family Pteropodidae, and were captured in diverse habitats, including natural and artificial caves, orchards, and man-made structures (Table S1). Archived tissues from these bats had previously been sampled for zoonotic surveillance for group A rotaviruses (RVA) (24) and hantaviruses (25).

FIG 1.

Sampling locations and species compositions of bats collected in different provincial regions of China. The filled circles represent the locations of sampled communities assigned numbers (see details in Table S1), with red representing PyV-positive communities or bat species and gray representing PyV-negative communities or bat species (species names of PyV-negative bats are not shown). The composition of collected bats in each region is represented by the colored rings with total numbers indicated. The colored region in the rings represents each positive bat family as per the key in the top right-hand corner. Every filled circle around the colored rings represents one bat species. The numbers of PyV-positive bats in each species are shown in parentheses. Abbreviations of provinces: XJ, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region; YN, Yunnan Province; GX, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region; FJ, Fujian Province; ZJ, Zhejiang Province. Abbreviations of bat genera: H., Hipposideros; A., Aselliscus; Rh., Rhinolophus; S., Scotophilus; Mi., Miniopterus; My., Myotis; T., Taphozous; Ro., Rousettus.

Our sampling records showed that these communities commonly contain one to four bat species (Table S1), suggesting different bat species can frequently encounter one another in these sympatric communities. To ascertain the genetic diversity and potential cross-species transmission of PyVs in bats, a broad-spectrum PyV nested PCR targeting the VP1 genes of known members within the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera (19) was performed using genomic DNAs extracted from archived rectal tissues derived from all 1,083 bats. Screening showed that PyVs were highly prevalent in every bat family. A total of 186 (17.2%) PyV-positive samples were detected from 15 bat species from 21 of 29 bat communities: 20 bats from Yunnan, 59 bats from Guangxi, 16 bats from Xinjiang, 74 bats from Fujian, and 17 bats from Zhejiang. With respect to the bat families (Fig. 1 and Table 1), 103 from 6 species of Rhinolophidae, 60 from 4 species of Vespertilionidae, 7 from 2 species of Hipposideridae, and 11, 2, and 3, respectively, from 1 species each of Emballonuridae, Miniopteridae, and Pteropodidae were PyV positive (Table S2). At the species level, Rhinolophus affinis, in the Rhinolophidae, widely distributed in southern China, yielded the highest number of positive bats (n = 64), while Myotis horsfieldii, in the Vespertilionidae collected in Fujian, showed the highest positivity rate: 66.6% (24/36).

TABLE 1.

Sampling of bats and positivity rates of PyVs in Chinese provinces

| Bat family and total positivity rate, % (no./total) | Bat species and total positivity rate, % (no./total) | Positivity rate in communities, % (no./total) | Community code (province and prefecture)a | No. of PyVsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhinolophidae, 24.9 (103/413) | Rhinolophus affinis, 34.0 (64/188) | 15.0 (9/60) | 1 (Yunnan Wenshan) | 4 |

| 31.8 (7/22) | 16 (Guangxi Fangchenggang) | 3 | ||

| 44.4 (12/27) | 17 (Guangxi Fangchenggang) | 4 | ||

| 41.3 (24/58) | 23 (Fujian Nanping) | 1 | ||

| 57.1 (12/21 | 24 (Fujian Sanming) | 1 | ||

| Rhinolophus sp. CN 2016, 11.1 (4/36) | 11.1 (4/36) | 2 (Yunnan Baoshan) | 2 | |

| Rhinolophus thomasi, 8.6 (3/35) | 7.1 (2/28) | 4 (Yunnan Dehong) | 2 | |

| 14.2 (1/7) | 20 (Guangxi Baise) | 1 | ||

| Rhinolophus pearsonii, 1.8 (1/55) | 3.1(1/32) | 4 (Yunnan Dehong) | 2 | |

| 0 (0/20) | 5 (Guangxi Hechi) | |||

| 0 (0/3) | 20 (Guangxi Baise) | |||

| Rhinolophus luctus, 0 (0/1) | 0 (0/1) | 4 (Yunnan Dehong) | ||

| Rhinolophus sinicus, 28.0 (14/50) | 28.6 (14/49) | 21 (Fujian Longyan) | 6 | |

| 0 (0/1) | 22 (Fujian Nanping) | |||

| Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, 35.4 (17/48) | 20.0 (2/10) | 25 (Zhejiang Zhoushan) | 1 | |

| 39.5 (15/38) | 26 (Zhejiang Zhoushan) | 4 | ||

| Vespertilionidae, 16.0 (60/376) | Scotophilus kuhlii, 6.3 (8/127) | 3.2 (1/31) | 8 (Guangxi Beihai) | 1 |

| 10.0 (4/40) | 9 (Guangxi Beihai) | 2 | ||

| 8.0 (1/13) | 10 (Guangxi Beihai) | 1 | ||

| 4.7 (2/43) | 18 (Guangxi Qinzhou) | 1 | ||

| Myotis davidii, 21.8 (12/55) | 21.8 (12/55) | 11 (Guangxi Guilin) | 4 | |

| Myotis horsfieldii, 66.7 (24/36) | 66.7 (24/36) | 24 (Fujian Sanming) | 3 | |

| Pipistrellus pipistrellus, 10.1(16/158) | 2.6 (2/76) | 27 (Xinjiang Ili) | 1 | |

| 25.5 (12/47) | 28 (Xinjiang Ili) | 3 | ||

| 5.7 (2/35) | 28 (Xinjiang Shihezi) | 1 | ||

| Hipposideridae, 3.3 (7/210) | Aselliscus stoliczkanus, 2.4 (1/42) | 2.6 (1/38) | 2 (Yunnan Baoshan) | 1 |

| 0 (0/4) | 19 (Guangxi Baise) | |||

| Hipposideros armiger, 0 (0/48) | 0 (0/3) | 2 (Yunnan Baoshan) | ||

| 0 (0/21) | 15 (Guangxi Chongzuo) | |||

| 0 (0/9) | 19 (Guangxi Baise) | |||

| 0 (0/6) | 20 (Guangxi Baise) | |||

| 0 (0/9) | 22 (Fujian Nanping) | |||

| Hipposideros larvatus, 8.9 (6/68) | 0 (0/10) | 6 (Guangxi Nanning) | ||

| 0 (0/20) | 7 (Guangxi Nanning) | |||

| 21.1 (4/19) | 16 (Guangxi Fangchenggang) | 2 | ||

| 20.0 (2/10) | 17 (Guangxi Fangchenggang) | 1 | ||

| 0 (0/5) | 19 (Guangxi Baise) | |||

| 0 (0/4) | 20 (Guangxi Baise) | |||

| Hipposideros pomona, 0 (0/44) | 0 (0/18) | 12 (Guangxi Liuzhou) | ||

| 0 (0/20) | 13 (Guangxi Laibin) | |||

| 0 (0/2) | 17 Guangxi Fangchenggang) | |||

| 0 (0/3) | 19 (Guangxi Baise) | |||

| 0 (0/1) | 20 (Guangxi Baise) | |||

| Hipposideros turpis, 0 (0/8) | 0 (0/8) | 19 (Guangxi Baise) | ||

| Emballonuridae, 31.4 (11/35) | Taphozous melanopogon, 31.4 (11/35) | 31.4 (11/35) | 15 (Guangxi Chongzuo) | 3 |

| Miniopteridae, 5.0 (2/40) | Miniopterus australis, 0 (0/1) | 0 (0/1) | 17 Guangxi Fangchenggang) | |

| Miniopterus schreibersii, 5.1 (2/39) | 0 (0/1) | 4 (Yunnan Dehong) | ||

| 5.3 (2/38) | 14 (Guangxi Chongzuo) | 2 | ||

| Pteropodidae, 33.3 (3/9) | Rousettus leschenaultii, 33.3 (3/9) | 33.3 (3/9) | 3 (Yunnan Baoshan) | 3 |

| Total, 17.2 (186/1,083) |

Extensive genetic diversity of polyomaviruses among bats.

The sampled PyVs revealed that bat species harbor diverse PyVs and that single bats can be infected with multiple PyVs (Table 1; detailed in Table S1). The screened partial VP1 of PyVs exhibited high genetic diversity; a total of 192 partial VP1 sequences (∼270 nucleotides [nt]) was obtained from 186 bats, with 180 samples from bats confirmed to harbor one PyV and the remaining 6 from bats with coinfections of two distinct PyVs (detailed in Table S3). Despite the short length of the fragments, these 192 VP1 sequences showed extensive diversity and could be classified into 44 well-supported clusters within the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera compared with homologous VP1 sequences of known PyVs (Fig. S1), with 46 to 90% nucleotide identities between clusters and 95 to 100% within clusters.

To further characterize the genetic diversity of these PyVs that clustered separately from other available known species, inverse PCR based on the partial VP1 sequences was employed to amplify the remaining fragments of the genomes. In some clusters, multiple samples were targeted for amplification of the genome sequences. As a result, 42 full-length genomes corresponding to 28 of the 44 VP1 clusters were obtained (Fig. S1). Based on the host species and the large tumor antigen (LTAg) identities to homologues from other available species, the 42 PyV strains were identified as 30 new bat-borne PyVs with nucleotide identities in the range of 68 to 90% to other 95 known PyVs (Table 2 and Fig. 2; detailed in Table S4).

TABLE 2.

New bat PyV genomes identified in Chinese bat hosts

| Host |

Polyomavirus |

Polyomavirus protein (no. of aad

) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Sample name | Year | Province | Communitya | Mitochondial fragment closest match (GenBank acc.b no.) | Identity, %c | GenBank acc. No. | Name of polyomavirus | Length | GC, % | Genus | LTAg | STAg | VP1 | VP2 | VP3 | Agno |

| 1 | PyVG-NJ21C | 2016 | Yunnan | 2 | Aselliscus stoliczkanus (KU573085) | 98.9 | LC426669 | Aselliscus stoliczkanus polyomavirus 1 | 5,245 | 42.7 | Alphapolyomavirus | 656 | 189 | 371 | 311 | 196 | |

| 2 | PyV23-FCC16 | 2016 | Guangxi | 16 | Hipposideros larvatus (JN247027) | 96.3 | LC426670 | Hipposideros larvatus polyomavirus 1 | 5,266 | 42.4 | Alphapolyomavirus | 854 | 187 | 440 | 230 | ||

| 3 | PyV15-NMC25 | 2016 | Guangxi | 14 | Miniopterus schreibersii (AY208138) | 99.3 | LC426671 | Miniopterus schreibersii polyomavirus 3 | 5,241 | 42.3 | Betapolyomavirus | 759 | 174 | 358 | 341 | 221 | 205 |

| 4 | PyV14-NMC23 | 2016 | Guangxi | 14 | Miniopterus schreibersii (AY208138) | 99.0 | LC426672 | Miniopterus schreibersii polyomavirus 4 | 4,926 | 42.2 | Alphapolyomavirus | 835 | 195 | 402 | 237 | ||

| 5 | PyV4-LPAC33 | 2015 | Guangxi | 11 | Myotis davidii (KM233172) | 94.7 | LC426673 | Myotis davidii polyomavirus 1 | 4,883 | 42.7 | Alphapolyomavirus | 846 | 190 | 397 | 235 | ||

| 6 | PyV35-SWBC1 | 2016 | Fujian | 24 | Myotis horsfieldii (MF143494) | 97.4 | LC426674 | Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 1 | 5,066 | 40.0 | Betapolyomavirus | 745 | 162 | 361 | 350 | 185 | |

| 7 | PyV33-SWBC37 | 2016 | Fujian | 24 | Myotis horsfieldii (MF143494) | 9.59 | LC426675 | Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 2 | 5,026 | 40.0 | Alphapolyomavirus | 718 | 187 | 367 | 326 | ||

| 8 | PyV19-SWBC1 | 2016 | Fujian | 24 | Myotis horsfieldii (MF143494) | 97.4 | LC426676 | Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 3 | 5,033 | 40.4 | Betapolyomavirus | 673 | 83 | 365 | 325 | 204 | 190 |

| 9 | PyV8-SHZC27 | 2016 | Xinjiang | 29 | Pipistrellus pipistrellus (AJ504443) | 95.4 | LC426677 | Pipistrellus pipistrellus polyomavirus 1 | 4,873 | 40.9 | Alphapolyomavirus | 837 | 186 | 403 | 239 | ||

| 10 | PyV22-DXC12 | 2016 | Guangxi | 17 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 96.6 | LC426701 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 1 | 5,097 | 41.4 | Alphapolyomavirus | 799 | 189 | 369 | 311 | 196 | |

| 11 | PyVB-FN02C | 2016 | Yunnan | 1 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.1 | LC426678 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 1 | 5,097 | 41.4 | Alphapolyomavirus | 799 | 189 | 369 | 311 | 196 | |

| 12 | PyVB-FN04C | 2016 | Yunnan | 1 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.1 | LC426679 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 1 | 5,097 | 41.4 | Alphapolyomavirus | 799 | 189 | 369 | 311 | 196 | |

| 13 | PyVC-FN15C | 2016 | Yunnan | 1 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.2 | LC426680 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 2 | 5,224 | 43.5 | Alphapolyomavirus | 715 | 190 | 371 | 311 | 196 | |

| 14 | PyV19-DXC32 | 2016 | Guangxi | 17 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 96.8 | LC426681 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 | 5,033 | 40.4 | Betapolyomavirus | 672 | 163 | 365 | 325 | 204 | 190 |

| 15 | PyV19-FCC38 | 2016 | Guangxi | 16 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.2 | LC426682 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 | 5,033 | 40.4 | Betapolyomavirus | 663 | 163 | 365 | 325 | 204 | 190 |

| 16 | PyV19-SWAC9 | 2016 | Fujian | 24 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.1 | LC426683 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 | 5,032 | 40.5 | Betapolyomavirus | 663 | 163 | 365 | 325 | 204 | 190 |

| 17 | PyV19-XDAC25 | 2016 | Fujian | 23 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.1 | LC426684 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 | 5,032 | 40.4 | Betapolyomavirus | 663 | 163 | 365 | 325 | 204 | 190 |

| 18 | PyV19-XDAC40 | 2016 | Fujian | 23 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.1 | LC426685 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 | 5,032 | 40.5 | Betapolyomavirus | 663 | 163 | 365 | 325 | 204 | 190 |

| 19 | PyVA-FN01C | 2016 | Yunnan | 1 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.1 | LC426686 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 | 5,032 | 40.4 | Betapolyomavirus | 683 | 163 | 365 | 325 | 204 | 190 |

| 20 | PyVA-FN06C | 2016 | Yunnan | 1 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.2 | LC426687 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 | 5,032 | 40.5 | Betapolyomavirus | 683 | 163 | 365 | 325 | 204 | 190 |

| 21 | PyV21-DXC30 | 2016 | Guangxi | 17 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.2 | LC426702 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 4 | 4,983 | 39.8 | Betapolyomavirus | 741 | 166 | 359 | 324 | 203 | 181 |

| 22 | PyV21-FCC23 | 2016 | Guangxi | 16 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.2 | LC426703 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 4 | 4,983 | 39.8 | Betapolyomavirus | 741 | 166 | 359 | 324 | 203 | 181 |

| 23 | PyVD-FN16C | 2016 | Yunnan | 1 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.2 | LC426688 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 4 | 4,983 | 39.8 | Betapolyomavirus | 741 | 166 | 359 | 324 | 203 | 181 |

| 24 | PyV23-DXC17 | 2016 | Guangxi | 17 | Rhinolophus affinis (DQ297582) | 97.1 | LC426689 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 5 | 5,266 | 42.4 | Alphapolyomavirus | 854 | 187 | 440 | 230 | ||

| 25 | PyV11-DZ11C | 2016 | Zhejiang | 26 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum korai (JN392460) | 97.2 | LC426690 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum polyomavirus 1 | 5,072 | 39.8 | Alphapolyomavirus | 801 | 193 | 368 | 310 | 195 | |

| 26 | PyV13-DZ26C | 2016 | Zhejiang | 26 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum korai (JN392460) | 97.2 | LC426691 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum polyomavirus 2 | 5,194 | 40.4 | Alphapolyomavirus | 717 | 189 | 370 | 311 | 196 | |

| 27 | PyV12-DZ13C | 2016 | Zhejiang | 26 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum korai (JN392460) | 97.2 | LC426692 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum polyomavirus 3 | 5,019 | 40.0 | Betapolyomavirus | 669 | 165 | 359 | 324 | 203 | 189 |

| 28 | PyV12-DZ15C | 2016 | Zhejiang | 26 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum korai (JN392460) | 97.2 | LC426693 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum polyomavirus 3 | 5,019 | 40.0 | Betapolyomavirus | 669 | 165 | 359 | 324 | 203 | 189 |

| 29 | PyVN-MS09C | 2016 | Yunnan | 4 | Rhinolophus pearsonii (KU531359) | 98.2 | LC426694 | Rhinolophus pearsonii polyomavirus 1 | 5,093 | 40.3 | Alphapolyomavirus | 660 | 196 | 369 | 311 | 242 | 189 |

| 30 | PyVM-MS09C | 2016 | Yunnan | 4 | Rhinolophus pearsonii (KU531359) | 98.2 | LC426695 | Rhinolophus pearsonii polyomavirus 2 | 5,225 | 41.0 | Alphapolyomavirus | 735 | 190 | 370 | 311 | 196 | |

| 31 | PyV28-YSC3 | 2016 | Fujian | 21 | Rhinolophus sinicus sinicus (KP257597) | 98.6 | LC426696 | Rhinolophus sinicus polyomavirus 1 | 5,443 | 44.4 | Alphapolyomavirus | 901 | 187 | 477 | 225 | ||

| 32 | PyV29-YSC17 | 2016 | Fujian | 21 | Rhinolophus sinicus sinicus (KP257597) | 98.8 | LC426697 | Rhinolophus sinicus polyomavirus 2 | 5,529 | 44.7 | Alphapolyomavirus | 910 | 187 | 495 | 225 | ||

| 33 | PyVE-NJ04C | 2016 | Yunnan | 2 | Rhinolophus sp. 2 KS2008 (EU434942) | 99.6 | LC426698 | Rhinolophus sp. CN 2016 polyomavirus 1e | 5,037 | 41.1 | Alphapolyomavirus | 662 | 189 | 372 | 311 | 195 | |

| 34 | PyVO-MS02C | 2016 | Yunnan | 4 | Rhinolophus thomasi (KY124333) | 98.6 | LC426699 | Rhinolophus thomasi polyomavirus 1 | 5,032 | 40.0 | Betapolyomavirus | 673 | 165 | 362 | 325 | 204 | 189 |

| 35 | PyVL-MS05C | 2016 | Yunnan | 4 | Rhinolophus thomasi (KY124333) | 98.6 | LC426700 | Rhinolophus thomasi polyomavirus 2 | 5,044 | 40.5 | Betapolyomavirus | 707 | 169 | 362 | 324 | 203 | 193 |

| 36 | PyVP-NJ33C | 2016 | Yunnan | 3 | Rousettus leschenaultii (DQ888669) | 99.9 | LC426704 | Rousettus leschenaulti polyomavirus 1 | 5,007 | 42.8 | Betapolyomavirus | 707 | 162 | 364 | 338 | 216 | 164 |

| 37 | PyVH-NJ32F | 2016 | Yunnan | 3 | Rousettus leschenaultii (DQ888669) | 99.1 | LC426705 | Rousettus leschenaulti polyomavirus 2 | 5,051 | 42.4 | Betapolyomavirus | 731 | 162 | 362 | 335 | 215 | 164 |

| 38 | PyV24-LSC2 | 2016 | Guangxi | 18 | Scotophilus kuhlii (EF543860) | 100.0 | LC426706 | Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 1 | 4,869 | 40.6 | Alphapolyomavirus | 823 | 191 | 392 | 241 | ||

| 39 | PyV2-YSAC17 | 2015 | Guangxi | 9 | Scotophilus kuhlii (EF543860) | 99.9 | LC426707 | Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 2 | 5,169 | 43.5 | Alphapolyomavirus | 875 | 188 | 465 | 218 | ||

| 40 | PyV1-YHAC9 | 2015 | Guangxi | 10 | Scotophilus kuhlii (EF543860) | 100.0 | LC426709 | Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 3 | 4,908 | 39.5 | Alphapolyomavirus | 802 | 187 | 396 | 238 | ||

| 41 | PyV1-YSAC16 | 2015 | Guangxi | 9 | Scotophilus kuhlii (EF543860) | 100.0 | LC426708 | Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 3 | 4,991 | 39.6 | Alphapolyomavirus | 802 | 187 | 396 | 238 | ||

| 42 | PyV16-LZC25 | 2016 | Guangxi | 15 | Taphozous melanopogon (EF584221) | 93.2 | LC426710 | Taphozous melanopogon polyomavirus 1 | 5,133 | 41.5 | Alphapolyomavirus | 744 | 190 | 377 | 310 | 193 | |

Community numbers. The locations of communities are shown in Fig. 1, with detailed information in Table S1.

acc., accession.

Percent identity of amplified bat mitochondrial gene fragments with the closest GenBank hit. The accession numbers are LC426433 to LC426476.

aa, amino acids.

PyV identified in a cryptic bat species (provisionally named Rhinolophus sp. CN 2016 polyomavirus 1), which awaits formal binomial classification of the host species, as the mitochondrial fragments showed only 90% ucleotide sequence identity with those of known bat species.

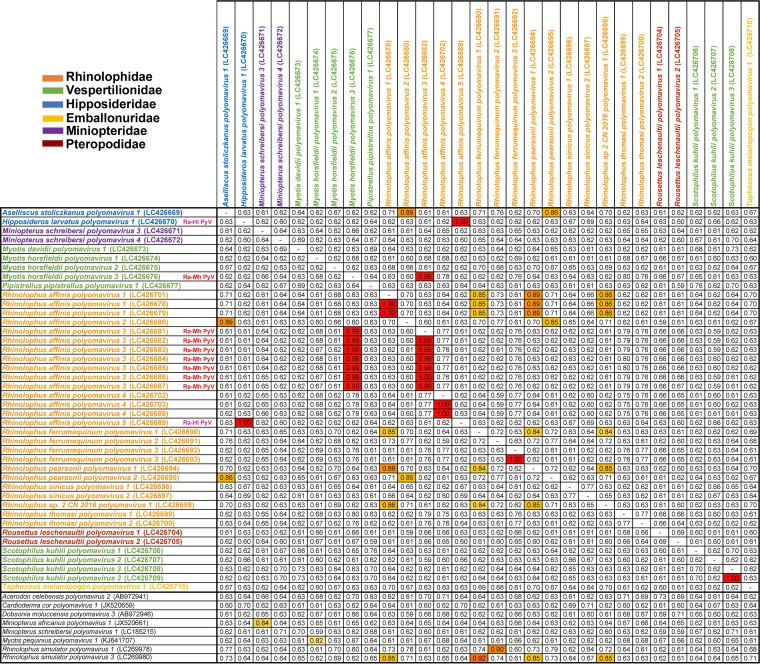

FIG 2.

Pairwise nucleotide identity (in decimal format) comparison of the LTAg genes of bat-borne PyVs identified in the present study. The LTAg coding sequences of 42 bat-borne PyV strains identified in the present study and 8 PyV references (row names) are compared with those of 30 newly proposed bat PyVs (column names). Cells are colored according to their nucleotide identity in red (>90%), orange (85 to 90%), yellow and light yellow (80 to 84%), and white (<80%).

For all bat samples from which PyVs genomes were obtained, a 1,840-bp mitochondrial DNA fragment encompassing the entire cytb, threonine and proline tRNAs, and part of the control region was amplified to corroborate the bat host species (Table 2) (26). The PyVs named in the present study were based on the binomial names of their host bat species and the chronological order of discovery, as per ICTV guidelines (27). Strikingly, we identified instances of the same PyV species (nucleotide identity > 99%) identified in more than one bat species. In detail, a PyV, herein provisionally named Rhinolophus affinis-Hipposideros larvatus polyomavirus (Ra-Hl PyV), was identified in both Rh. affinis and Hipposideros larvatus bats, i.e., Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 5 and Hipposideros larvatus polyomavirus 1 (Fig. 2). Similarly, PyVs collectively named Rhinolophus affinis-Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus (Ra-Mh PyV) were identified in Rh. affinis and My. horsfieldii bats, i.e., Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 and Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 3 (Fig. 2).

Among the newly identified single-host PyVs (Fig. 2), 19 PyVs shared nucleotide identities in the range of 68 to 83% with the closest previously described species or with each other in the LTAg coding sequences and therefore were considered to be new PyV species according to the species demarcation criterion of 15% genetic divergence in the LTAg gene (27). Seven PyVs shared 86 to 90% nucleotide identity with the closest known species or with each other in the LTAg gene and therefore showed insufficient divergence to be assigned as new virus species despite host species divergence; however, all were identified for the first time in their specific bat hosts and from bats separated by considerable geographical distances (≥564 ± 328 km) (Fig. 1 and Table S2).

Phylogenetic analysis and identification of host-switching events.

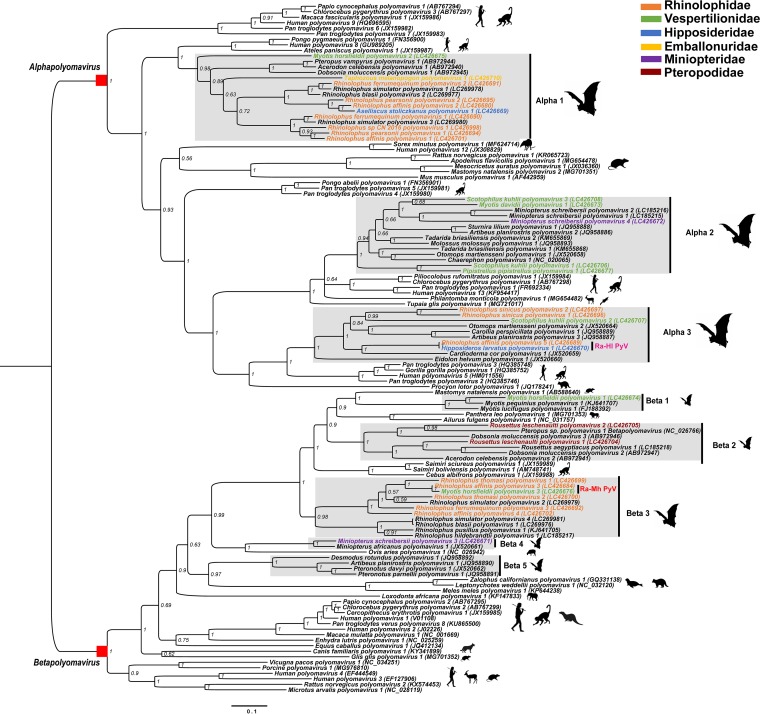

In order to understand the phylogenetic relationships of new PyVs and analyze the strains with high similarity sampled from different bat species, a phylogenetic tree was built from the LTAg amino acid sequences including the 30 new PyVs and 95 Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus species recognized by the ICTV (detailed in Table S4) (Fig. 3). The new bat PyVs clustered within the Alphapolyomavirus (n = 20) and Betapolyomavirus (n = 10) genera along with 38 known bat PyVs. Within each viral genus, bat PyV sequences grouped into eight clusters, referred to as Alpha 1 to 3 and Beta 1 to 5. Among these new PyVs, two viruses, Ra-Hl PyV in Alpha 3 of Alphapolyomavirus and Ra-Mh PyV in Beta 3 of Betapolyomavirus, were identified in bat hosts of different families living in the same community, suggestive of two viral host-switching events. Additionally, Alpha 1 showed a third putative PyV host-switching event: Aselliscus stoliczkanus polyomavirus 1 carried by bats of the Hipposideridae family clustered with PyVs carried by bats of the Rhinolophidae family (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Bayesian phylogenetic tree of the PyV LTAg protein sequences. The tree was constructed with 156 LTAg amino acid sequences from the 30 PyVs identified in the present study and 126 PyV references in the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera available in GenBank. Bat PyV clusters including the new PyVs are named and shaded in gray. Names of new PyVs are colored differently according to their host species within the Chiropteran family, as shown in the top left-hand corner. Silhouettes of the mammalian hosts of PyVs are shown alongside each clade. Bayesian posterior probability supporting the branching is shown next to the branches.

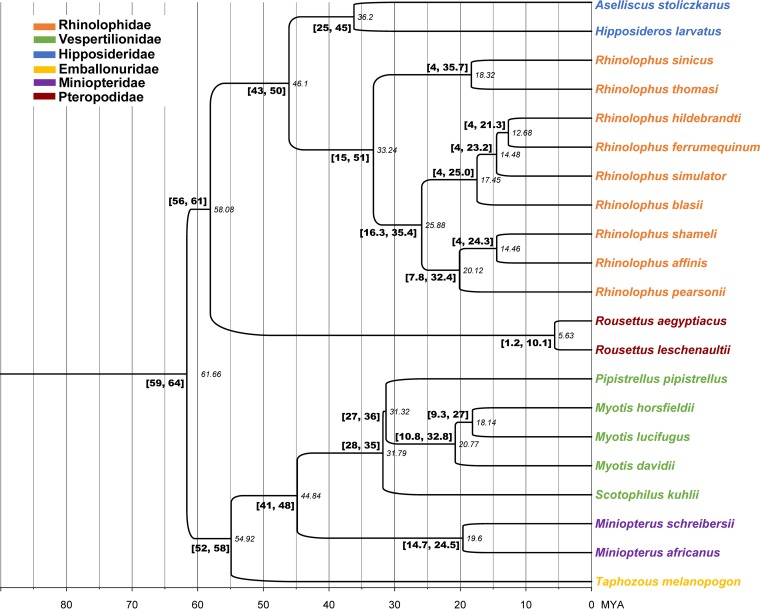

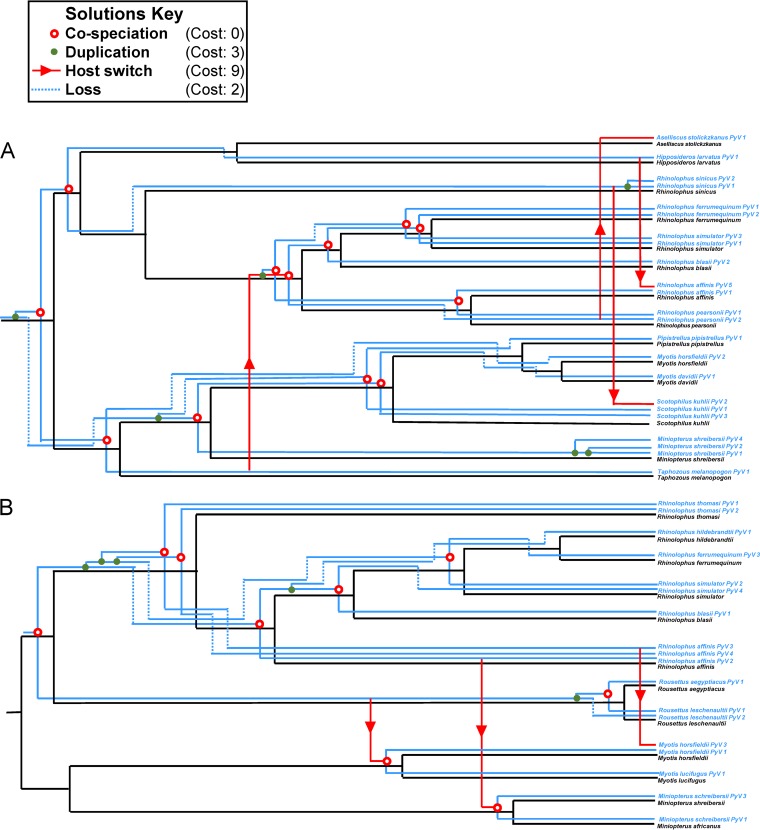

The presence of multiple clusters in both PyV genera and the clades containing PyVs identified from different bat families prompted us to analyze the phylogeny in the context of the host codivergence employing JANE software. The bat host phylogenetic tree containing all species considered for this study was derived from TimeTree (timetree.org) (28), where the results from multiple studies are combined to provide an accurate consensus of the divergence between different species (Fig. 4). The cophylogenetic analyses of the new viruses and their respective bat hosts were performed separately for both Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera by JANE considering five cost schemes for the events (Table 3). Although the five cost schemes produced solutions with better costs than the random distributions and all suggested lineage duplications with host-switching events, schemes IV and V generated solutions in the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus maximizing the number of codivergence events while minimizing the number of host-switching events. Therefore, consistent with the evident lack of widespread host-switching events, this study assumed solutions based on cost scheme V, which was more conservative than other schemes (Fig. 5). The significance of the JANE solution costs was tested against random solutions in JANE by permutating the tips of viruses and hosts. The best-supported solution in cost scheme V (cost = 82) for Alphapolyomavirus indicated 12 cospeciations, 6 duplications, 14 losses, and 4 host-switching events (Table 3 and Fig. 5A), while the best solution (cost = 66) in Betapolyomavirus indicated 9 cospeciations, 5 duplications, 12 losses, and 3 host-switching events (Table 3 and Fig. 5B). Therefore, the analyses indicated virus-host codivergence mixed with numerous intrahost lineage duplications in both viral genera and were supported in multiple cost schemes despite differences in the direction of the host-switching event. The three putative host-switching events suggested above (Fig. 2) were significantly supported by the JANE solutions (Table 3). Additionally, four putative ancient and interfamily host-switching events were also inferred; for instance, Scotophillus kuhlii polyomavirus 2 (Vespertilionidae family) was suggested to derive from an ancestral host-switching event from Rhinolophus PyV (Rhinolophidae family) (Fig. 5A) and the five cost schemes supported this event; however, cost scheme II suggested an ancestral host-switching event from Scotophilus kuhlii PyV that derived from the Rhinolophus sinicus PyVs.

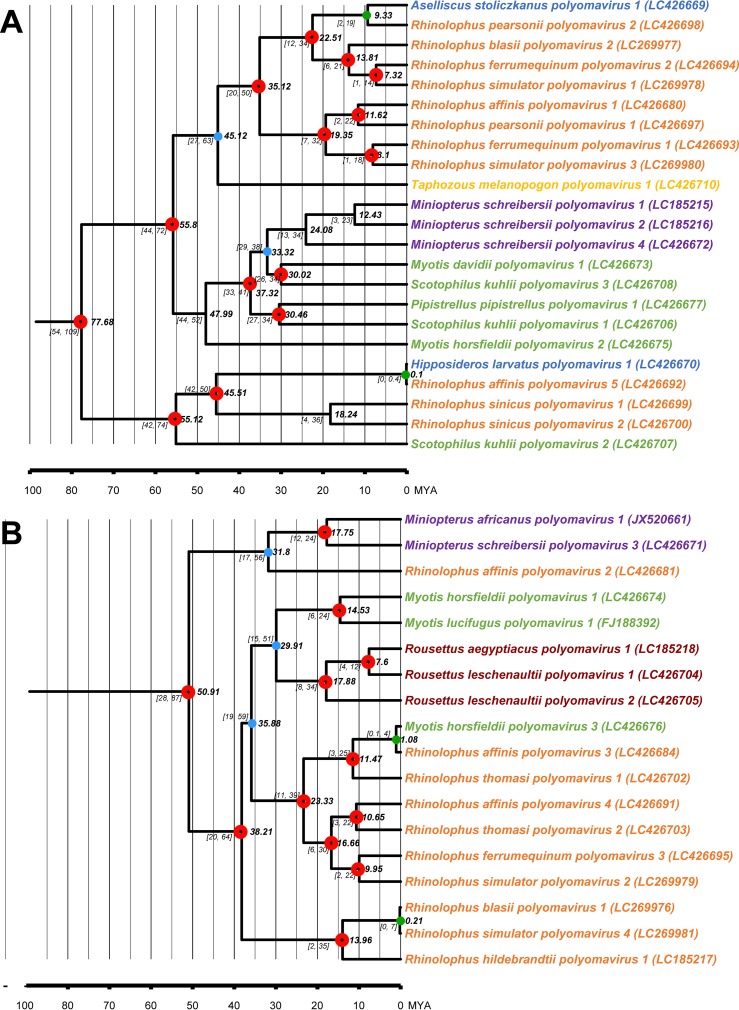

FIG 4.

Dating the tMRCA of host bat species employing TimeTree data set. The bat species were identified based on bat mitochondrial gene sequences (colored according to the bat families). The divergence time between species was determined with TimeTree. The timescale at the bottom and the tMRCAs shown next to the branches are in millions of years (MYA) before the present. Node ages of the tMRCAs of bat species, with confidence intervals, are shown next to the branches.

TABLE 3.

JANE solutions for alpha- and betapolyomaviruses under different cost schemes

| Virus genus | Parameter category | Parameter | Value or resulta

for indicated cost scheme |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | |||

| Not specified | Cost per event | Codivergence | 0 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 0 |

| Duplication | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Duplication with host switch | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 9 | ||

| Loss | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Failure to diverge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Alphapolyomavirus | Events per solution | Codivergence | 8 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Duplications | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||

| Duplication with host switch | 11 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Losses | 1 | 22 | 22 | 14 | 14 | ||

| Failures to diverge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cost of solution | 15 | 10 | −12 | 42 | 82 | ||

| Simulation (n = 500) | Better random solutions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Minimum | 17 | 12 | −10 | 56 | 124 | ||

| Maximum | 21 | 17 | −5 | 77 | 169 | ||

| Mean | 19.4 | 15.0 | −7.0 | 68.8 | 149.2 | ||

| SD | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 8.4 | ||

| Host-switching events | Taphozous melanopogon polyomavirus 1 → Rhinolophus polyomaviruses | R | R | Y | Y | Y | |

| Rhinolophus pearsonii polyomavirus 2 → Aselliscus stoliczkanus polyomavirus 1 | R | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Rhinolophus sinicus polyomavirus 1 → Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 1 polyomavirus 2 | Y | R | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Hipposideros larvatus polyomavirus 1 → Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 5 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | ||

| Betapolyomavirus | Events per solution | Codivergence | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Duplications | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Duplication with host switch | 9 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 3 | ||

| Losses | 3 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 12 | ||

| Failures to diverge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cost of solution | 12 | 8 | −9 | 34 | 66 | ||

| Simulation (n = 500) | Better random solutions | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Minimum | 12 | 9 | −8 | 39 | 82 | ||

| Maximum | 16 | 13 | −4 | 60 | 130 | ||

| Mean | 14.6 | 11.2 | −5.9 | 51.4 | 110.8 | ||

| SD | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 7.9 | ||

| Host-switching events | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 2 → Myotis polyomaviruses | R | R | R | Y | Y | |

| Rhinolophus polyomaviruses → Myotis polyomaviruses | R | N | N | Y | Y | ||

| Rhinolophus. afinis polyomavirus 3 → Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 3 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

Abbreviations for host-switching events in the solutions: Y, present; R, present but inferred with the opposite direction; N, not present in the solution.

FIG 5.

Cophylogenetic comparisons for bat PyVs in the Alphapolyomavirus (A) and Betapolyomavirus (B) genera with their hosts by JANE. The best-supported solution (red dashed lines) of Alphapolyomavirus and Betapolyomavirus was tested against random solutions by permutating the tips of viruses and hosts. The blue phylogenies were reconstructed representing the divergence of viral species in the Alphapolyomavirus and Betapolyomavirus genera and mapped against the black phylogenies showing the host divergence. Symbols for the annotations of events and their respective cost are shown in the key.

Effects of host-switching events on the virus-host coevolution of PyVs.

The high support for a virus-host codivergence model inferred by JANE solutions was further tested by assessing Mantel’s correlation between the divergence among PyV genome sequences and the evolutionary distance reflected in the host phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4 and Table 4). Of note is that the analysis based on the evolutionary distance between the cytb sequences of hosts led to identical results. Significant correlations between host and PyV divergence per genus were found when considering the 42 genomes identified in China. In detail, the correlations between bat hosts and PyVs in the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera were 0.49 (P < 1 × 10−4) and 0.64 (P < 6 × 10−4), respectively. The geographical location of the bat hosts was shown to have a low correlation and, consequently, low impact upon virus divergence. Such an observation was further substantiated by the increase of the correlation exhibited in both genera when African PyVs of related bat hosts species were considered (Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera: 0.88 and 0.87, respectively). The effect of host-switching events included in JANE solutions was assessed by estimating the correlation when excluding eight sequences related to those events; thus, the correlation indices increased to 0.88 (P < 2 × 10−4) and 0.87 (P < 1 × 10−4) in the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera, respectively, which suggested that the removed PyVs shared a lower correlation with the divergence of their respective hosts than other PyVs retained in the analysis.

TABLE 4.

Correlation analyses of genetic divergences between PyVs and bat hosts

| Group of PyVs for analysis | No. of samples | Correlation |

Partial correlationb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Geography | Host | Geography|hosta | Geography|host | Host|geography | ||

| Current study | 23 | Alphapolyomavirus | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.49 |

| P value | 0.38 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 0.14 | ||||

| 19 | Betapolyomavirus | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.62 | |

| P value | 0.03 | 6.0 × 10−4 | 5.9 × 10− 3 | ||||

| Including Zambian Rhinolophus PyVs | 25 | Alphapolyomavirus | −0.14 | 0.54 | −0.06 | −0.13 | 0.54 |

| P value | 0.92 | 1.0 × 10-4 | 0.67 | ||||

| 22 | Betapolyomavirus | 0.22 | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.66 | |

| P value | 0.11 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 0.41 | ||||

| Removing the following: | |||||||

| Aselliscus stoliczkanus polyomavirus 1 (LC426669) | 21 | Alphapolyomavirus | −0.13 | 0.88 | −0.06 | −0.16 | 0.88 |

| Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 2 (LC426707) | P value | 0.10 | 2.0 × 10−4 | 0.40 | |||

| Taphozous melanopogon polyomavirus 1 (LC426710) | |||||||

| Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 5 (LC426689) | |||||||

| Removing the following: | |||||||

| Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 3 (LC426676) | 18 | Betapolyomavirus | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.08 | −0.09 | 0.88 |

| Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 1 (LC426674) | P value | 0.22 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 0.26 | |||

| Rhinolophus simulator polyomavirus 4 (LC269981) | |||||||

| Rhinolophus blasii polyomavirus 1 (LC269976) | |||||||

Correlation between evolutionary distance among hosts and geographical distances of their detected location.

Partial correlation controlling for the effect of the variable after the vertical bar.

Dating the divergence times of PyV species and host switching.

The assumed cospeciation events confirmed by the correlation analysis were used to calibrate the inference of PyV divergence in BEAST software. Therefore, the data from the hosts (Fig. 4) were combined with the JANE analysis to enable a more accurate estimation of the times to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) of the PyVs. Nodes suspected to represent host-switching events were not calibrated to avoid biasing the results. The inferred dating of the speciation events in Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera were found to largely match with the host divergence when comparing the confidence intervals (CI) of tMRCA (red circles in Fig. 6). In detail, the majority of estimated node ages in the Alphapolyomavirus (14/17 [82%]) and Betapolyomavirus (12/16 [75%]) genera overlapped with the host divergence event date estimates, respectively. Nevertheless, putative host-switching events were further supported by CI dates which were more recent than the divergence between the respective hosts (see green dots in Fig. 6). The three host-switching events were estimated at 0 to 19 (95% CI) million years ago (MYA), which is significantly lower than the current consensus for the tMRCA of their respective bat hosts, 43 to 50 MYA for Hipposideridae and Rhinolophidae and 59 to 64 MYA for Vespertilionidae and Rhinolophidae. In addition to the previously identified host-switching events, some nodes showed tMRCA that were outside the expected confidence intervals according to their host species. Two and three nodes were found in the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus, respectively (see blue dots in Fig. 6). Such tMRCA of PyVs younger than their host tMRCA indicated that these nodes perhaps derived from ancient host-switching events.

FIG 6.

Calibrated estimation of divergence between alphapolyomaviruses (A) and betapolyomaviruses (B). The timescale at the bottom of both panels and tMRCAs shown next to the branches are in millions of years before the present (MYA). Median age of the tMRCAs of and PyVs are shown next to the branches. Nodes with open red circles indicate that the range of divergence in the virus overlaps with the range of divergence of the host. Light blue discs mark ancient nodes for which the 95% confidence interval (CI) range for tMRCA does not overlap the host CI range. The green discs indicate putative host-switching events where the 95% CI range is younger than that of the host.

The host-switching event in the Alpha 3 cluster (Fig. 3 and Table 5), Ra-Hl PyV, involved bats of Rh. affinis (family Rhinolophidae) and H. larvatus (family Hipposideridae). Screening results showed that Ra-Hl PyV was detected in two bat species from two different communities. An Ra-Hl PyV-specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay showed that the viral load in Rh. affinis was low, while no qPCR positives were detected in H. larvatus. At a genomic level, Ra-Hl PyVs identified in different bat species showed 100% identity, corroborating screening results. The tMRCA estimation suggested that this host-switching event occurred in 0 to 0.4 MYA. In summary, the Ra-Hl PyV was originally harbored by Rh. affinis in Guangxi and transmitted recently to H. larvatus present in the same caves.

TABLE 5.

Summary of identified host-switching events

| Host-switching event (HS) | Host species 1 |

Host species 2 |

Genetic analysis |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species name | Virus name | Positivity rate of nested PCR in each community | No. of recovered genomes | qPCR positive number (mean CTa value) | Species name | Virus name | Positive rate of nested PCR in each community | No. of recovered genomes | No. of qPCR-positive samples (mean CT value) | LTAg cluster | Genomic identity of viruses between hosts (%) | Cophylogenetic analysis | tMRCA estimation of host-switching eventb | |

| HS1: Ra-Hl PyV | Rh. affinis (family Rhinolophidae) | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 5 (Ra-Hl PyV) | Community 16, 1/22; community 17, 8/27 (both in Guangxi) | 1 full genome and 8 partial genomes | 2 positives in 1 community (35.56–37.91) | H. larvatus (family Hipposideridae) | Hipposideros larvatus polyomavirus 1 (Ra-Hl PyV) | Community 16, 3/19; community 17, 2/10 (both in Guangxi) | 1 full genome and 4 partial genomes | 0 | Alpha 2 | 100 | From Rh. affinis to H. larvatus | 0–0.4 MYA |

| HS2: Ra-Mh PyV | Rh. affinis (family Rhinolophidae) | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 (Ra-Mh PyV) |

Community 1, 2/60 (Yunnan); community 16, 3/22; community 17, 2/27 (both in Guangxi); community 23, 24/58; community 24, 12/21 (both in Fujian) |

7 full genomes and 43 partial genomes | 8 positives in community 23 (24.17–34.83) | My. horsfieldii (family Vespertilionidae) | Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 3 (Ra-Mh PyV) | Community 24, 23/36 (in Fujian) | 1 full genome and 22 partial genomes | 7 in community 24 (27.16–36.63) | Beta 3 | 97–99 | From Rh. affinis to My. horsfieldii | 0.1–4 MYA |

| HS3 | Rhinolophus spp. (family Rhinolophidae) | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 2 | Community 1, 2/60 (Yunnan) | 1 full genome and 1 partial genomes | NAc | A. stoliczkanus (family Hipposideridae) | Aselliscus stoliczkanus polyomavirus 1 | Community 2, 1/38 (in Yunnan) | 1 full genome | NA | Alpha 1 | 87 | From Rhinolophus spp. to A. stoliczkanus | 2–16 MYA |

CT, threshold cycle.

In 95% highest posterior density.

NA, not available.

The host-switching event in the Beta 3 cluster (Fig. 3 and Table 5), Ra-Mh PyV, involved bats of Rh. affinis (family Rhinolophidae) and My. horsfieldii (family Vespertilionidae). The PyV strains of Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 and Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 3 were highly similar, with 97 to 99% genomic identity. Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 was detected in five communities of Rh. affinis bats in Yunnan, Guangxi, and Fujian provinces (23% [43/188]). Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 3 had a high positivity rate in My. horsfieldii bats within a single community where, notably, Rh. affinis and My. horsfieldii species roosted together. Geographically, Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 was widely distributed in Rh. affinis hosts. The VP1 tree showed that Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 and Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 3 did not form independent subclusters (Fig. S1). A qPCR assay for Ra-Mh PyV detected 8 positives in Rh. affinis and 7 positives in My. horsfieldii, suggestive of ongoing interhost transmission of this virus between two bat species. The tMRCA estimation suggested that this host-switching event occurred in 0.1 to 4 MYA. Consequently, Ra-Mh PyV is a widely distributed virus in Rh. affinis in southern China and transmission likely occurred recently from Rh. affinis to My. horsfieldii in at least one community with high frequency. For both HS1 and HS2, the detection rate of qPCR assay was lower than that of the nested PCR assay, reflecting the lower sensitivity of the former. Furthermore, the qPCR suggested that the viral loads of targeted PyVs in bats were very low, while the nested PCR and amplicon sequencing revealed the presence of mutations in the targeted PyVs indicative of strain diversity (Fig. S1).

The third putative host switching in the Alpha 1 cluster (Fig. 3 and Table 5) occurred between Aselliscus stoliczkanus (family Hipposideridae) and Rhinolophus spp. (family Rhinolophidae). Aselliscus stoliczkanus polyomavirus 1 exhibited 87% and 86% nucleotide identities with Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 2 and Rhinolophus pearsonii polyomavirus 2, respectively (Fig. 2). The two sampling locations of the Rhinolophus species were, respectively, 731 km and 86 km apart from the cave in which the single Aselliscus stoliczkanus polyomavirus 1-positive sample was collected. The best-supported solution for the cophylogenetic analysis revealed that the lineage of Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 2 gave rise to Aselliscus stoliczkanus polyomavirus 1. The tMRCA estimation suggested that this host-switching event occurred between 2 and 16 MYA.

DISCUSSION

The current study uncovered extensive diversity of bat PyV species across five provincial regions in China. We have identified 28 new and distinguishable PyVs from 15 bat species in 6 families (27), which considerably increases our knowledge of both the genomic diversity and the evolution of PyVs. A high prevalence of multiple PyV species and evidence for rare virus transmission events were identified among sympatric bats. To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide such a comprehensive characterization of PyVs and their virus-host relationships in a large number of sympatric mammalian communities.

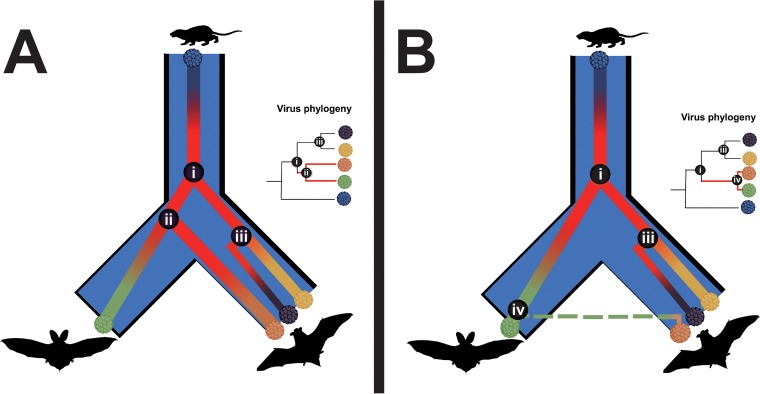

The observed virus-host relationships suggest that codivergence is the major evolutionary process generating the extant PyV diversity in bats, as has been observed in multiple mammalian species (8). Interestingly, PyVs identified in different horseshoe bat species in sympatric communities showed high (85 to 90%) genomic identities clustering with each other, though these were highly restricted in different horseshoe bat species and exhibited a strong signal of codivergence rather than host switching. Therefore, the diverse bat PyVs, like other mammalian PyVs, exemplify host specificity (2); however, in the present study, evidence of interfamily host-switching events of PyVs in mammals was found among the bat families Rhinolophidae, Hipposideridae, and Vespertilionidae. Previously, short-range intragenus host-switching events of PyVs were identified in African horseshoe bats, occurring between Rh. simulator and Rh. blasii in a single Zambian cave (9). There are four common points to these host-switching events. (i) The cross-transmission of PyVs occurred between limited bat species. For all the observed cases, there is only one primary host and one secondary host species, and importantly, each example involved a horseshoe bat species. (ii) The primary host and secondary host species were collected from a sympatric bat community where dwelled two or more bat species with frequent contact. (iii) Compared with the primary host species, the prevalence of PyV infection in the secondary host species is geographically restricted. (iv) The PyV strains in two host species exhibited high (97 to 100%) genomic identities. These findings suggest that PyV host-switching events exist though are restricted to specific sympatric bat communities involving horseshoe bats. Considering the evidence supporting the presence of host-switching events during the divergence of PyV species, we propose a modification to the currently recognized evolutionary model of intrahost codivergence (Fig. 7A). The model illustrates infrequent host-switching events and explains the high similarity of virus sequences despite the divergence between associated host species (Fig. 7B). This scheme provides a useful model to understand the evolution of PyVs in other hosts and, potentially, the modeling of bat zoonoses and the transmission of other small DNA viruses in other mammals, including humans.

FIG 7.

Models of PyV evolution in mammals by intrahost divergence with infrequent host-switching events. (A) Currently recognized intrahost divergence of PyVs suggested viral duplication with no host switching; (B) intrahost divergence with infrequent host-switching events was proposed here. Divergence events are marked i to iv, representing viral duplication before the divergence of host species (i), codivergence with the host species (ii), viral duplication in the same host species (iii), and host switching to a diverged (susceptible) host species (iv). The phylogenies represent the expected phylogenetic relationship for each respective case, with the events marked at the nodes.

One of the ICTV criteria for PyV species designation is a genetic distance of the LTAg coding sequence of ≥15%. This cutoff value is not strict, as exemplified by two PyVs identified in two different species of squirrel monkeys which shared 89% sequence identity but were recognized as two separate PyV species (27). In the present study, we have discovered numerous new PyVs carried by diverse bat species, all exhibiting 86 to 90% genomic identities with their closest known species or with each other. These should be considered new PyV species since all were detected exclusively in distinct bat species in different areas and exhibited strict host specificity. Examples include the PyVs identified in different Rhinolophus bat species from China and Africa sharing 89 to 90% genomic identity. The correlation and genetic selection analyses reported here have shown that the high sequence identity of different PyVs carried by different host species was due to the codivergence with strong negative selection of PyVs in respective hosts. Regarding the relationship between Chinese and African bat PyVs referred to above, it is of interest that hepadnaviruses (pararetroviruses with DNA genomes) identified in Chinese Rhinolophus bats in another study (29) were also found to exhibit the closest genetic relation (79.6 to 79.7% nt identity) with viruses carried by African Rhinolophus bats (29), thereby suggesting that codivergence of DNA viruses within their Rhinolophus bat hosts is relatively common for multiple viral families.

The findings presented here may have possible implications for the study of zoonotic transmissions involving highly virulent viral pathogens in bats. For example, horseshoe bats within the family Rhinolophidae have been found to harbor genetically diverse severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-like coronaviruses, which acted as major reservoirs for spillover of SARS coronavirus to humans (30). Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus has similarly been associated with severe disease and lethal respiratory infections, mostly in Saudi Arabia. Recently, swine acute diarrhea syndrome (SADS) coronavirus has been associated with high morbidity and mortality in pig populations in Guangdong province, China, in close proximity to the origin of the SARS pandemic, and striking similarities between the SADS and SARS outbreaks in geographical, temporal, ecological, and etiological settings exist (31). Notably, 2019-nCoV is a newly discovered agent that is also most closely related to betacoronaviruses from horseshoe bats (32). We consider it noteworthy that in the present study we identified host-switching events of the normally highly host-restricted PyVs within the bat families Rhinolophidae and Vespertilionidae. Whether this reflects a greater propensity for host switching in these bat families than in others and what mechanisms are involved require further functional studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

The procedures for sampling bats in this study were reviewed and approved by the Administrative Committee on Animal Welfare of the Institute of Military Veterinary Medicine (Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee Authorization permits JSY-DW-2010-02 and JSY-DW-2016-02). All live animals were maintained and handled according to the Principles and Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Medicine (33).

Sample information.

The tissues of 1,083 bats in the present study were archived and subpacked samples were stored at –80°C following collection between 2015 and 2016 from 29 communities distributed across the provinces of Yunnan, Fujian, Zhejiang, Guangxi, and Xinjiang in China. Detailed information for sampled bats is shown in Table S1.

As part of the regional viral surveillance of a bat-borne zoonosis program, the bats collected in Yunnan and Xinjiang provinces were also pooled and subjected to next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based viral metagenomic analysis (34). Briefly, nucleic acids were amplified by random-hexamer primer amplification prior to Illumina sequencing. The resulting sequencing reads were quality trimmed and compared (using BLASTx) to reference nonredundant (nr) sequences of all viruses (NCBI taxid: 10239). Though numerous short reads of new PyVs were also detected by this method, the data were not used for downstream analysis because these reads cannot be assembled into full genome of PyV. Reference sequences used in this study are detailed in Table S4.

Polyomavirus screening and complete genome sequencing.

Approximately 50-mg samples of rectal and lung tissues from the 208 bats in communities 1 to 4 collected in Yunnan province were pooled and subjected to viral metagenomic analysis, as per our previously published method (34). Due to the complexity of the PyV-related reads detected by the viral metagenomic analyses, the PyV-specific nested PCR protocol (35) based on the VP1 gene developed by Johne et al. in 2005 (19) was employed to screen all metagenomic samples, and partial VP1 amplicons were cloned and bidirectionally sequenced by standard methods. In addition, the PCR was expanded to screen genomic DNA extracts from rectal tissues of bats collected from other Chinese provinces.

Genomic DNA from each bat tissue sample was extracted manually using the TIANamp genomic DNA kit (Tiangen, China), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. PCR screening employed PCR master mix (Tiangen). Positive PCR amplicons were purified by gel extraction (Axygen, NY), sequenced directly on a 3730xl DNA analyzer (Genewiz, China) to confirm homology to PyVs, and then ligated into vector pMD-18T (TaKaRa, Japan) and used to transform Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells (Tiangen). In order to detect potential coinfection of multiple PyVs in each positive sample, VP1 amplicons from 186 positive bats were cloned into vectors, and four clones derived from each amplicon were sequenced. GenBank accession numbers of these 192 partial PyV VP1 sequences are detailed in Table S3.

Oligonucleotide primers for inverse PCRs for amplification of the 5-kb PyV genomes were designed based on the partial VP1 sequences. Multiple pairs of heminested degenerate primers were subsequently designed for VP1 clusters which showed close phylogenetic relationships (Table S5). All ∼5-kb products were amplified from bat genomic DNA by inverse PCR employing the PrimeSTAR MAX DNA polymerase (TaKaRa), purified by gel extraction (Axygen), cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, CA), and bidirectionally sequenced by primer walking to Phred quality scores of >30 with the 3730xl DNA analyzer (Genewiz). After removal of vector sequences, the full genomes of each PyV were assembled by Geneious software using the partial VP1 and 5-kb products.

To detect the viral loads of Ra-Hl PyV and Ra-Mh PyV in their bat hosts, two real-time qPCR assays were established based on the noncoding control region (NCRR) of each PyV (Table S5). The Ra-Hl PyV qPCR assay was performed to screen all gut samples of bats collected in communities 16 and 17 in Guangxi (Table S1). The Ra-Mh PyV qPCR assay was performed to screen all the gut samples of bats collected in community 24 in Fujian (Table S1). In order to minimize contamination, the DNAs were reextracted from the tissues and were amplified using a probe qPCR kit (TaKaRa) as per the manufacturer’s protocol on a Stratagene Mx3000P.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The pairwise identity of the LTAg coding sequences was calculated with Sequence Demarcation Tool (SDT) v1.2 (36). The nucleotide sequences of PyV genes and proteins were aligned using MAFFT under the algorithm FFT-NS-i (37). Phylogenetic trees were inferred using MrBayes v3.2, with 106 generations chains to ensure <0.01 standard deviation between the split frequencies and 25% of generations discarded as burn-in (38), as described previously (39). For the LTAg multiple-sequence alignment, a mixed-substitution model was used to explore the best-substitution model when inferring the topology. On the other hand, the best-fitting nucleotide substitution model, the PyV LTAg coding sequence alignment, was chosen with MEGA7 (40) by choosing the lowest Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

Cophylogenetic analysis.

Mapping the divergence of PyV species to the divergence among hosts was performed with JANE 4 (41). The solutions for the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera were generated with costs for cospeciation, duplication, loss, and host-switching events following five different cost schemes (Table 3) to assess solutions with different evolutionary considerations. The three first schemes follow the polyomavirus codivergence report by Madinda et al. (42): scheme I favors codivergence and assigning a cost to duplication and loss events; scheme II favors codivergence and loss events, as prevalence may have been low at some time in the past; scheme III is similar to scheme I but equates costs and codivergence events; scheme IV assigns a higher cost to lineage duplication and the highest cost to host-switching events, based on the rare evidence for such events; and scheme V assigns an even higher cost to lineage duplication events and, also, the highest cost to host-switching events. The input was the phylogenetic tree for the host species from TreeTime (28), the phylogenetic trees for the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera inferred with amino acid sequences of the LTAg protein, and the table indicating the association between hosts and viruses.

Correlation analysis.

The divergence correlation between the hosts and PyVs in the Alpha- and Betapolyomavirus genera was assessed by applying Mantel’s correlation tests to the pairwise evolutionary distance matrices for hosts and viral samples in both genera with 104 repetitions. Additionally, the matrices were also analyzed against the geographical distance between sampling points, and partial correlations between host and polyomavirus distance matrices were estimated controlling for the correlation with the geographical distance. The correlation analysis was performed considering three sets of data per genus: (i) considering only samples identified in China, (ii) considering samples identified in China and samples identified in Africa (9), and (iii) removing samples from item ii identified in the cophylogenetic analysis as related to host-switching events.

Dating of tMRCA for polyomavirus species.

The times to most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) for hosts were derived from the consensus in TreeTime and using multiple studies covering the host species determined by the cytb sequences (43–47). The tMRCA for viral samples were estimated with Bayesian analyses conducted as 4 independent Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains of 10 million generations each, sampled every 1,000 generations (BEAST v2.4.6 [48]). The LTAg gene multiple-sequence alignment was used to infer the divergence times among PyVs. The general time-reversible substitution model with gamma-distributed rate variation across sites and a proportion of invariable sites (GTR+G+I) was assumed. Other settings included an uncorrelated exponential relaxed molecular clock for PyV model with a Yule speciation model. This model was chosen with the highest likelihood compared to other models with the PathSampler application in BEAST v2.4.6 package. Calibrations for both genera are summarized in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Calibration of nodes in BEAST for tMRCA of polyomavirus species

| PyV genus | No. | Virus name | Host species | Divergence (MYA) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Rangea | ||||

| Alphapolyomavirus | 1 | Hipposideros larvatus polyomavirus 1 | Hipposideros larvatus | 46 | 43–50 |

| Rhinolophus sinicus polyomavirus 1 | Rhinolophus sinicus | ||||

| Rhinolophus sinicus polyomavirus 2 | |||||

| 2 | Miniopterus schreibersii polyomavirus 1 | Miniopterus schreibersii | 45 | 41–48 | |

| Miniopterus schreibersii polyomavirus 2 | |||||

| Miniopterus schreibersii polyomavirus 4 | |||||

| Myotis davidii polyomavirus 1 | Myotis davidii | ||||

| Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 2 | Myotis horsfieldii | ||||

| Pipistrellus pipistrellus polyomavirus 1 | Pipistrellus pipistrellus | ||||

| Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 1 | Scotophilus kuhlii | ||||

| Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 3 | |||||

| 3 | Rhinolophus blasii polyomavirus 2 | Rhinolophus blasii | 17.45 | 4–25 | |

| Rhinolophus ferrumequinum polyomavirus 2 | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum | ||||

| Rhinolophus simulator polyomavirus 1 | Rhinolophus simulator | ||||

| 4 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 1 | Rhinolophus affinis | 20.12 | 7.8–32.4 | |

| Rhinolophus pearsonii polyomavirus 1 | Rhinolophus pearsonii | ||||

| 5 | Pipistrellus pipistrellus polyomavirus 1 | Pipistrellus pipistrellus | 31.79 | 28–35 | |

| Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 1 | Scotophilus kuhlii | ||||

| 6 | Myotis davidii polyomavirus 1 | Myotis davidii | 31.79 | 28–35 | |

| Scotophilus kuhlii polyomavirus 3 | Scotophilus kuhlii | ||||

| Betapolyomavirus | 1 | Miniopterus africanus polyomavirus 1 | Miniopterus africanus | 19.6 | 14.7–24.5 |

| Miniopterus schreibersii polyomavirus 3 | Miniopterus schreibersii | ||||

| 2 | Myotis horsfieldii polyomavirus 1 | Myotis horsfieldii | 18.4 | 9.3–27 | |

| Myotis lucifugus polyomavirus 1 | Myotis lucifugus | ||||

| 3 | Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 3 | Rhinolophus affinis | 33.24 | 15–51 | |

| Rhinolophus affinis polyomavirus 4 | |||||

| Rhinolophus thomasi polyomavirus 1 | Rhinolophus thomasi | ||||

| Rhinolophus thomasi polyomavirus 2 | |||||

| 4 | Rhinolophus blasii polyomavirus 1 | Rhinolophus blasii | 17.45 | 4–25 | |

| Rhinolophus simulator polyomavirus 4 | Rhinolophus simulator | ||||

| 5 | Rousettus aegyptiacus polyomavirus 1 | Rousettus aegyptiacus | 5.63 | 1.2–10.1 | |

| Rousettus leschenaulti polyomavirus 1 | Rousettus leschenaultii | ||||

In 95% highest posterior density.

Accession number(s).

For the sequences obtained in this study, the SRA accession numbers are SRR9644024 for Yunnan bats and SRX6405658 for Xinjiang bats. The partial PyV VP1 sequences are available in GenBank under accession numbers LC426477 to LC426668 (Table S3).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the NSFC-Xinjiang Joint Fund (U1503283) and the NSFC General Program (31572529).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeCaprio JA, Imperiale MJ, Major EO. 2013. Polyomaviridae, p 1633–1661. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moens U, Krumbholz A, Ehlers B, Zell R, Johne R, Calvignac-Spencer S, Lauber C. 2017. Biology, evolution, and medical importance of polyomaviruses: an update. Infect Genet Evol 54:18–38. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr MJ, Gonzalez G, Teeling EC, Sawa H. 2020. Bat polyomaviruses: a challenge to the strict host-restriction paradigm within the mammalian Polyomaviridae, p 87–118. In Corrales-Aguilar E, Schwemmle M (ed), Bats and viruses: current research and future trends. Caister Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. 2008. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 319:1096–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalianis T, Hirsch HH. 2013. Human polyomaviruses in disease and cancer. Virology 437:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dela Cruz FN, Giannitti F, Li L, Woods LW, Del Valle L, Delwart E, Pesavento PA. 2013. Novel polyomavirus associated with brain tumors in free-ranging raccoons, western United States. Emerg Infect Dis 19:77–84. doi: 10.3201/eid1901.121078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez-Losada M, Christensen RG, McClellan DA, Adams BJ, Viscidi RP, Demma JC, Crandall KA. 2006. Comparing phylogenetic codivergence between polyomaviruses and their hosts. J Virol 80:5663–5669. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00056-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buck CB, Van Doorslaer K, Peretti A, Geoghegan EM, Tisza MJ, An P, Katz JP, Pipas JM, McBride AA, Camus AC, McDermott AJ, Dill JA, Delwart E, Ng TFF, Farkas K, Austin C, Kraberger S, Davison W, Pastrana DV, Varsani A. 2016. The ancient evolutionary history of polyomaviruses. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005574. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr M, Gonzalez G, Sasaki M, Dool SE, Ito K, Ishii A, Hang’ombe BM, Mweene AS, Teeling EC, Hall WW, Orba Y, Sawa H. 2017. Identification of the same polyomavirus species in different African horseshoe bat species is indicative of short-range host-switching events. J Gen Virol 98:2771–2785. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moens U, Calvignac-Spencer S, Lauber C, Ramqvist T, Feltkamp MCW, Daugherty MD, Verschoor EJ, Ehlers B, ICTV Report Consortium. 2017. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol 98:1159–1160. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson DE, Reeder DM. 2005. Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference, 3rd ed, vol 1 Order Chiroptera. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr M, Gonzalez G, Sasaki M, Ito K, Ishii A, Hang’ombe BM, Mweene AS, Orba Y, Sawa H. 2017. Discovery of African bat polyomaviruses and infrequent recombination in the large T antigen in the Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol 98:726–738. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misra V, Dumonceaux T, Dubois J, Willis C, Nadin-Davis S, Severini A, Wandeler A, Lindsay R, Artsob H. 2009. Detection of polyoma and corona viruses in bats of Canada. J Gen Virol 90:2015–2022. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.010694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagrouch Z, Sarwari R, Lavergne A, Delaval M, De Thoisy B, Lacoste V, Verschoor EJ. 2012. Novel polyomaviruses in South American bats and their relationship to other members of the family Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol 93:2652–2657. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tao Y, Shi M, Conrardy C, Kuzmin IV, Recuenco S, Agwanda B, Alvarez DA, Ellison JA, Gilbert AT, Moran D, Niezgoda M, Lindblade KA, Holmes EC, Breiman RF, Rupprecht CE, Tong S. 2013. Discovery of diverse polyomaviruses in bats and the evolutionary history of the Polyomaviridae. J Gen Virol 94:738–748. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.047928-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima FES, Cibulski SP, Witt AA, Franco AC, Roehe PM. 2015. Genomic characterization of two novel polyomaviruses in Brazilian insectivorous bats. Arch Virol 160:1831–1836. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2447-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi S, Sasaki M, Nakao R, Setiyono A, Handharyani E, Orba Y, Rahmadani I, Taha S, Adiani S, Subangkit M, Nakamura I, Kimura T, Sawa H. 2015. Detection of novel polyomaviruses in fruit bats in Indonesia. Arch Virol 160:1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Moore NE, Murray ZL, McInnes K, White DJ, Tompkins DM, Hall RJ. 2015. Discovery of novel virus sequences in an isolated and threatened bat species, the New Zealand lesser short-tailed bat (Mystacina tuberculata). J Gen Virol 96:2442–2452. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johne R, Enderlein D, Nieper H, Müller H. 2005. Novel polyomavirus detected in the feces of a chimpanzee by nested broad-spectrum PCR. J Virol 79:3883–3887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3883-3887.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Z, Yang L, Ren X, He G, Zhang J, Yang J, Qian Z, Dong J, Sun L, Zhu Y, Du J, Yang F, Zhang S, Jin Q. 2015. Deciphering the bat virome catalog to better understand tha ecological diversity of bat viruses and the bat origin of emerging infectious diseases. ISME J 2015:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantalupo PG, Buck CB, Pipas JM. 2017. Complete genome sequence of a polyomavirus recovered from a Pomona leaf-nosed bat (Hipposideros pomona) metagenome data set. Genome Announc 5:e01053-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01053-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra N, Fagbo SF, Alagaili AN, Nitido A, Williams SH, Ng J, Lee B, Durosinlorun A, Garcia JA, Jain K, Kapoor V, Epstein JH, Briese T, Memish ZA, Olival KJ, Lipkin WI. 2019. A viral metagenomic survey identifies known and novel mammalian viruses in bats from Saudi Arabia. PLoS One 14:e0214227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh H-M, Chiang H-L, Tsai L-C, Lai S-Y, Huang N-E, Linacre A, Lee J-I. 2001. Cytochrome b gene for species identification of the conservation animals. Forensic Sci Int 122:7–18. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00403-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He B, Huang X, Zhang F, Tan W, Matthijnssens J, Qin S, Xu L, Zhao Z, Yang L, Wang Q, Hu T, Bao X, Wu J, Tu C. 2017. Group A rotaviruses in Chinese bats: genetic composition, serology, and evidence for bat-to-human transmission and reassortment. J Virol 91:e02493-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02493-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu L, Wu J, Li Q, Wei Y, Tan Z, Cai J, Guo H, Yang LE, Huang X, Chen J, Zhang F, He B, Tu C. 2019. Seroprevalence, cross antigenicity and circulation sphere of bat-borne hantaviruses revealed by serological and antigenic analyses. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007545. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puechmaille SJ, Gouilh MA, Piyapan P, Yokubol M, Mie KM, Bates PJ, Satasook C, Nwe T, Bu SSH, Mackie IJ, Petit EJ, Teeling EC. 2011. The evolution of sensory divergence in the context of limited gene flow in the bumblebee bat. Nat Commun 2:573. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calvignac-Spencer S, Polyomaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, Feltkamp MC, Daugherty MD, Moens U, Ramqvist T, Johne R, Ehlers B. 2016. A taxonomy update for the family Polyomaviridae. Arch Virol 161:1739–1750. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-2794-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S, Stecher G, Suleski M, Hedges SB. 2017. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol Biol Evol 34:1812–1819. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nie FY, Lin XD, Hao ZY, Chen XN, Wang ZX, Wang MR, Wu J, Wang HW, Zhao G, Ma RZ, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. 2018. Extensive diversity and evolution of hepadnaviruses in bats in China. Virology 514:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lau SK, Woo PC, Li KS, Huang Y, Tsoi H-W, Wong BH, Wong SS, Leung S-Y, Chan K-H, Yuen K-Y. 2005. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:14040–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou P, Fan H, Lan T, Yang X-L, Shi W-F, Zhang W, Zhu Y, Zhang Y-W, Xie Q-M, Mani S, Zheng X-S, Li B, Li J-M, Guo H, Pei G-Q, An X-P, Chen J-W, Zhou L, Mai K-J, Wu Z-X, Li D, Anderson DE, Zhang L-B, Li S-Y, Mi Z-Q, He T-T, Cong F, Guo P-J, Huang R, Luo Y, Liu X-L, Chen J, Huang Y, Sun Q, Zhang X-L-L, Wang Y-Y, Xing S-Z, Chen Y-S, Sun Y, Li J, Daszak P, Wang L-F, Shi Z-L, Tong Y-G, Ma J-Y. 2018. Fatal swine acute diarrhoea syndrome caused by an HKU2-related coronavirus of bat origin. Nature 556:255–258. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou P, Yang X-L, Wang X-G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si H-R, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang C-L, Chen H-D, Chen J, Luo Y, Guo H, Jiang R-D, Liu M-Q, Chen Y, Shen X-R, Wang X, Zheng X-S, Zhao K, Chen Q-J, Deng F, Liu L-L, Yan B, Zhan F-X, Wang Y-Y, Xiao G-F, Shi Z-L. 3 February 2020. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministry of Science and Technology. 2006. Principles and guidelines for laboratory animal medicine. Ministry of Science and Technology, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- 34.He B, Li Z, Yang F, Zheng J, Feng Y, Guo H, Li Y, Wang Y, Su N, Zhang F, Fan Q, Tu C. 2013. Virome profiling of bats from Myanmar by metagenomic analysis of tissue samples reveals more novel mammalian viruses. PLoS One 8:e61950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orba Y, Kobayashi S, Nakamura I, Ishii A, Hang’ombe BM, Mweene AS, Thomas Y, Kimura T, Sawa H. 2011. Detection and characterization of a novel polyomavirus in wild rodents. J Gen Virol 92:789–795. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.027854-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muhire BM, Varsani A, Martin DP. 2014. SDT: a virus classification tool based on pairwise sequence alignment and identity calculation. PLoS One 9:e108277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol 61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carr M, Kawaguchi A, Sasaki M, Gonzalez G, Ito K, Thomas Y, Hang'ombe BM, Mweene AS, Zhao G, Wang D, Orba Y, Ishii A, Sawa H. 2017. Isolation of a simian immunodeficiency virus from a malbrouck (Chlorocebus cynosuros). Arch Virol 162:543–548. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conow C, Fielder D, Ovadia Y, Libeskind-Hadas R. 2010. Jane: a new tool for the cophylogeny reconstruction problem. Algorithms Mol Biol 5:16. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madinda NF, Ehlers B, Wertheim JO, Akoua-Koffi C, Bergl RA, Boesch C, Akonkwa DB, Eckardt W, Fruth B, Gillespie TR, Gray M, Hohmann G, Karhemere S, Kujirakwinja D, Langergraber K, Muyembe JJ, Nishuli R, Pauly M, Petrzelkova KJ, Robbins MM, Todd A, Schubert G, Stoinski TS, Wittig RM, Zuberbuhler K, Peeters M, Leendertz FH, Calvignac-Spencer S. 2016. Assessing host-virus codivergence for close relatives of Merkel cell polyomavirus infecting African great apes. J Virol 90:8531–8541. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00247-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]