Abstract

Pseudomonas brassicacearum and related species of the P. fluorescens complex have long been studied as biocontrol and growth-promoting rhizobacteria involved in suppression of soilborne pathogens. We report here that P. brassicacearum Q8r1-96 and other 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG)-producing fluorescent pseudomonads involved in take-all decline of wheat in the Pacific Northwest of the USA can also be pathogenic to other plant hosts. Strain Q8r1-96 caused necrosis when injected into tomato stems and immature tomato fruits, either attached or removed from the plant, but lesion development was dose dependent, with a minimum of 106 CFU mL−1 required to cause visible tissue damage. We explored the relative contribution of several known plant-microbe interaction traits to the pathogenicity of strain Q8r1-96. Type III secretion system (T3SS) mutants of Q8r1-96 injected at a concentration of 108 CFU mL−1, were significantly less virulent, but not consistently, as compared to the wild-type strain. However, a DAPG-deficient phlD mutant of Q8r1-96 was significantly and consistently less virulent as compared to the wild type. Strain Q8r1-96acc, engineered to over express ACC deaminase, caused a similar amount of necrosis as the wild type. Cell-free culture filtrates of strain Q8r1-96 and pure DAPG also cause necrosis in tomato fruits. Our results suggest that DAPG plays a significant role in the ability of Q8r1-96 to cause necrosis of tomato tissue but other factors also contribute to the pathogenic properties of this organism.

Keywords: 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol; ACC deaminase; tomato; Pseudomonas

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas brassicacearum and related species of the P. fluorescens complex are ubiquitous soil microorganisms that have long been studied for their beneficial plant growth-promoting and biocontrol properties (Raaijmakers & Weller 1998; Schlatter et al. 2017). For example, strains of P. brassicacearum (formerly P. fluorescens genotype D) are biocontrol agents against soilborne pathogens and are responsible for take-all decline (TAD), a natural suppression of take-all disease in monoculture wheat fields of the Pacific Northwest (PNW), USA (Schlatter et al. 2017). However, these organisms have also been reported as “quasi” or minor pathogens that blur the boundaries between saprophytism and parasitism and under certain conditions can cause disease (Belimov et al. 2007; Brazelton et al. 2008; Kwak et al. 2012). For example, P. brassicacearum Q8r1-96 reduced the germination of wheat seeds and caused lesions on wheat roots in a cultivar- and dose-dependent manner (Kwak et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2018). P. brassicacearum strains Am3 and 520–1 have either growth-promoting or pathogenic effects on tomato depending on the dose and environmental conditions (Belimov et al. 2007). Inoculation of unripe tomatoes with Am3R or 520–1 resulted in necrosis of the fruits; however, these strains also induced tomato root elongation and plant growth due to the presence of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase, which hydrolyzes the immediate precursor of the plant hormone ethylene (Belimov et al. 2007; Glick et al. 1995). Belimov et al. (2007) suggested that the ACC deaminase of Am3 helps to promote growth in tomato by masking the pathogenic properties of this bacterium.

Type III protein secretion systems (T3SSs) play an essential role in the interaction of pathogenic and symbiotic gram-negative bacteria with their plant hosts. The T3SS-mediated secretion of effector molecules into host cells helps pathogens to suppress the plant defense response system and favor infection (Cornelis 2010; Mavrodi et al. 2011; Tampakaki et al. 2014). The genome of P. brassicacearum Q8r1-96 carries genes encoding a functional T3SS and effectors, many of which have homologs in the plant pathogen P. syringae (Loper et al. 2012). Although the type III effectors of Q8r1-96 were fully functional and capable of suppressing PAMP- and effector-triggered plant immunity, the inactivation of genes encoding structural components of the T3SS apparatus did not reduce the rhizosphere competence and biocontrol properties (Mavrodi et al. 2011). Yang et al. (2018) later found that the same TTSS mutants were identical to wild type Q8r1-96 in ability to reduce seed germination and root growth of wheat.

2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol (DAPG) is an antibiotic produced by P. brassicacearum and some other members of the P. fluorescens complex (Loper et al. 2012). It has broad spectrum antibiotic activity and can inhibit organisms ranging from viruses, bacteria, and fungi to higher plants and mammalian cells (Brazelton et al. 2008; Haas and Keel 2003; Kwak et al. 2011; Maurhofer et al. 1995; Yang et al. 2018). Studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae revealed that DAPG has a complex mode of action and affects target organisms by disturbing cell membrane permeability, triggering reactive oxygen burst, and interrupting cell homeostasis (Kwak et al. 2011). Other studies have indicated that DAPG treatment results in the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (Gleeson et al. 2010; Troppens et al. 2013). The DAPG biosynthesis locus includes two operons phlACBDE and phlF, which function in synthesis, export, and regulation of the antibiotic (Bangera and Thomashow 1999). The product of phlD is responsible for the synthesis of monoacetylphloroglucinol (MAPG), which is then converted to DAPG through the action of enzymes encoded by phlA, phlC, and phlB (Yang and Cao 2012). Yang et al. (2018) reported that production of DAPG was the primary mechanism by which strain Q8r1-96 reduced the germination of wheat seeds when applied at a dose of 106 seed−1 or higher.

Although it is generally accepted that the pathogenicity of “quasi” (minor) pathogens is modulated by environmental conditions, the plant genotype, presence of wounds, and the pathogen dose, the exact mechanism of this phenotype remains poorly understood (Cho et al.1975). Accordingly, the objective of our research was to determine if Q8r1-96, which is typical of strains responsible for TAD in the PNW, is pathogenic on tomato as are other P. brassicacearum strains. Secondly, to gain insight into the mechanism of pathogenicity of P. brassicacearum Q8r1-96. We show that Q8r1-96 and several closely related strains of the P. fluorescens complex are quasi-pathogens of tomato. We also show that a mutant of Q8r1-96 deficient in DAPG production was significantly and consistently reduced in the ability to rot tomato fruits as compared to the wild type, suggesting that DAPG production is an important determinant of the pathogenicity of P. brassicacearum on tomato.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and mutants.

The phenotypes and source of bacterial strains used in this study are summarized in Table 1. P. brassicacearum Q8r1-96 was isolated from the rhizosphere of wheat grown in soil from a field near Quincy, WA in the state of take-all decline (Raaijmakers and Weller 1998). The other DAPG-producing Pseudomonas strains have been previously described by McSpadden Gardener et al. (2000) and Weller et al. (2007). The study employed three type III secretion system (T3SS) mutants of Q8r1-96, Q8r1-96ΔOPQR, Q8r1-96rscV, and Q8r1-96rspL, which have been previously described (Mavrodi et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2018). The study also used the isogenic mutant Q8r1-96phlD, in which the key DAPG biosynthesis gene phlD was interrupted by the insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene cassette (Yang et al. 2018).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strains | Characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. brassicacearum Q8rl-96 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from Quincy, WA; DAPG+; Rifr; Genotype D | Raaijmakers & Weller 1998 |

| Q8r1-96ΔOPQR | T3SS mutant of Q8r1-96, Δ(rspOP-rscQR)::aacC1; DAPG+; Rifr; Gmr | Mavrodi et al. 2011 |

| Q8r1-96rspL | T3SS mutant of Q8r1-96, rspL::aph; DAPG+; Rifr; Kanr | Mavrodi et al. 2011 |

| Q8r1-96rscV | T3SS mutant of Q8r1-96, rscV::aph; DAPG+; Rifr; Kanr | Mavrodi et al. 2011 |

| Q8r1-96phlD | DAPG-deficient (DAPG-) mutant of Q8r1-96, phlD::aph; Rifr; Kanr | Yang et al. 2018 |

| Q8r1-96acc | The mini-Tn7ΩGm-PtacacdS-carrying derivative of Q8r1-96 that constitutively expresses ACC deaminase; DAPG+; Rifr; Gmr | This study |

| P. protegens Pf-5 | Cotton rhizosphere isolate from Texas; DAPG+; Genotype A | Loper et al. 2012 |

| P. fluorescens Q2–87 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from Quincy, WA; DAPG+; Genotype B | Mavrodi et al. 2001 |

| Pseudomonas sp. STAD384 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from Stillwater, OK; DAPG+; Genotype C | McSpadden Gardener et al. 2000 |

| P. brassicacearum L5.1–96 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from Lind, WA; DAPG+; Genotype D | Raaijmakers & Weller 2001 |

| Pseudomonas sp. Q2–2 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from Quincy, WA; DAPG+; Genotype E | McSpadden Gardener et al. 2000 |

| Pseudomonas sp. JMP6 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from the Netherlands; DAPG+; Genotype F | McSpadden Gardener et al. 2000 |

| Pseudomonas sp. FF1R18 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from Fargo, ND; DAPG+; Genotype G | McSpadden Gardener et al. 2000 |

| Pseudomonas sp. FFL1R22 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from Fargo, ND; DAPG+; Genotype J | McSpadden Gardener et al. 2000 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens 1M1 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from Lind, WA; DAPG+; Genotype L | Raaijmakers & Weller 2001 |

| Pseudomonas sp. D27B1 | Wheat rhizosphere isolate from the Netherlands; DAPG+; Genotype M | McSpadden Gardener et al. 2000 |

Rifr, rifampicin resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance; aph, aminoglycoside 3’-phosphotransferase; aacC1, gentamicin acetyltransferase 3–1; T3SS, type III protein secretion system; DAPG, 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol; ACC deaminase, 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase.

To construct Q8r1-96acc, the 1,033-bp ACC deaminase (acdS) gene of P. putida UW4 (Glick 1995) was amplified by PCR with primers acc1 (5′-ATA TAC ATA TGA ACC TGA ATC GTT TTG-3′) and acc2 (5′-AAA AAA GCT TAG CCG TTG CGA AAC-3′) and KOD DNA polymerase (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA). The amplicon was digested with NdeI and HindIII and cloned in gene expression vector pCYB2 (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) under the control of Ptac promoter and ribosome binding site (RBS). The acdS gene together with Ptac and RBS was then re-amplified using nested PCR with primer sets prnF (5′-CTG TTG ACA ATT AAT CAT CGG CTC GTA TAA TG-3′) - accR (5′-AGC TGG GTT CTA GCC GTT GCG AAA CAG GAA G-3′) and prn2F (5’-GGG GAC AAG TTT GTA CAA AAA AGC AGG CTC TGT TGA CAA TTA ATC-3′) - 2R (5′-GGG GAC CAC TTT GTA CAA GAA AGC TGG GTT CTA-3′) and cloned into the Gateway entry plasmid vector pMK2010 (House et al. 2004) with BP Clonase II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and single-pass sequenced to confirm the absence of mutations. The promoter-RBS-acdS fusion was then swapped into pBK-mini-Tn7ΩGm-ccdB (a Gateway destination vector derived from pBK-mini-Tn7ΩGm with ccdB-Camr cassette flanked by attR1 and attR2 sites) using LR Clonase II (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The construct was then introduced into Q8r1-96 resulting in the integration of miniTn7ΩGm-PtacacdS into a neutral chromosomal site and the constitutive expression of ACC deaminase. All strains were routinely cultured in King’s medium B (King et al. 1954) and stored as frozen glycerol stocks at −80°C.

Determination of the pathogenicity of P. brassicacearum in tomato fruits.

The pathogenicity of P. brassicacearum wild type and its mutants and other DAPG producers on tomato was determined essentially as described by Belimov et al. (2007). Cherry tomato plants (cv. Sweet 100) were grown in plastic pots (30 cm diam. × 40 cm deep) filled with Miracle-Gro potting mix (Scotts Miracle-Gro Company, Marysville, OH), in a greenhouse at 27°C and a dark/light cycle of 12 h. Immature green fruits were picked when they were approximately 2.5 cm in diameter, surface sterilized by soaking in a solution of 1% commercial bleach for 5 min, rinsed three times with sterile water and allowed to air dry. Bacterial suspensions ranging from 0 to 108 CFU mL−1 in sterile water with 0.85% NaCl were injected (10-μl aliquot) into the central pith of each fruit, with six fruits per treatment and each fruit serving as a replicate. Control fruits were injected with 0.85% NaCl in aqueous solution. After ten days of incubation at room temperature (23°C) in the dark, the fruits were cut in half and rated for necrosis on a scale of 0–3: 0= no tissue necrosis; 1 = light brown necrosis on less than 1/3 of the fruit; 2 = brown necrosis on 1/3 of the fruit; and 3 = brown to black necrosis on greater than 1/3 of the fruit. To fulfill Koch’s postulates, immature tomato fruits on the vine were injected (107 CFU mL−1) with strain Q8r1-96 and evaluated for necrosis as described above.

Determination of the effects of Q8r1-96 culture filtrates and pure DAPG on tomato fruits.

Strains Q8r1-96 and Q8r1-96phlD were inoculated into 2 mL of KMB broth in test tubes, incubated at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm for 48 h), and then filtered to remove the bacterial cells (0.2-μm filter, Acrodisc 25 mm Syringe Filter, Life Sciences). Cell-free filtrates (10 μl) were injected into detached tomato fruits one, three or four times (once each day) as described above. Pure DAPG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc) was injected at concentrations of 25 μg mL−1, 100 μg mL−1 and 3 mg mL−1. DAPG was dissolved in methanol (3 mg mL−1) and then further diluted with sterile water. Aliquots (10 μl) were injected into immature tomato fruits one, three or four times as described above.

Determination of the pathogenicity P. brassicacearum Q8r1-96 in tomato stems.

Tomato plants, grown for 30 days in pots with potting mix, were wounded by passing a 0.5-mm-diameter syringe needle through the stem line at a height of 10–15 cm above the soil. A 10-μl aliquot of a suspensions of Q8r1-96 (108 CFU mL−1) in 0.85% NaCl was then injected into the wound with a pipette and a 10-μl pipette tip. A 0.85% NaCl solution was used as a control. For each experiment, three plants were used for each treatment, and 25 days after injection, a cross section of the stem was cut with a razor blade to determine the amount of necrosis.

Bacterial colonization of tomato fruits.

A 10-μl aliquot of a suspension of strain Q8r1-96 (107 CFU mL−1) in 0.85% NaCl was injected into immature tomato fruits attached to the vine as described above. After ten days, tomato fruits were harvested from the vine, cut into small pieces (2 mm × 2 mm), vortexed for 1 min in 20 mL of sterile water in a 50-mL centrifuge tube, followed by sonication in a water bath for 1 min. Each tomato was processed separately. Bacterial population sizes were determined by the PCR-based dilution-endpoint assay (Bankhead et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2011). Briefly, each tomato washing solution was serially diluted in a 96-well plate (100 μl added into a well with 200 μ of water) and then 50 μl of each dilution was transferred to wells of a plate with 200 μl of 1/3x KMB broth supplemented with ampicillin, chloramphenicol, cycloheximide and rifampicin (1/3×KMB+++Rif) (Bankhead et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2011). Growth in each well was determined after three days of incubation at room temperature using a Model 680 microplate reader (Biotek). An optical density at 600 nm > 0.1 was scored as positive for growth. The population size of Q8r1-96 was based on the final dilution that contained growth and was positive for phlD by PCR using primers (B2BF and BPR4) specific for the DAPG biosynthesis operon (Bankhead et al. 2016; Mavrodi et al. 2012).

Data analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed by using appropriate parametric and nonparametric procedures with the STATISTIX 8.0 software (Analytical Software, St. Paul, MN). Mean comparisons among treatments were performed by either the Fisher’s protected least-significant-difference test (P=0.05) or the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test (P=0.05). All experiments were conducted at least twice with similar results.

RESULTS

Symptoms on tomato fruits and stems caused by P. brassicacearum.

Strain Q8r1-96 caused significant necrosis and decay of the inside of immature tomato fruits when injected at a dose of 107 or 108 CFU mL−1 (Fig. 1). Results were the same for inoculated fruits either attached or removed from the vine. Symptoms ranged from light brown necrosis in the tissue around the injection site to black necrosis and decay of most of the fruit. The amount of necrosis and tissue damage varied considerably among replicate fruits injected at the same time (ratings ranged from 0 to 3) and among experiments (Fig. 1). A dose of 106 CFU mL−1 caused only browning around the injection site and lower doses caused no symptoms (Table 2). Although not shown here, P. brassicacearum L5.1–96 from a TAD field near Lind, WA (Landa et al. 2003) produced symptoms in tomato fruits identical to those caused by strain Q8r1-96.

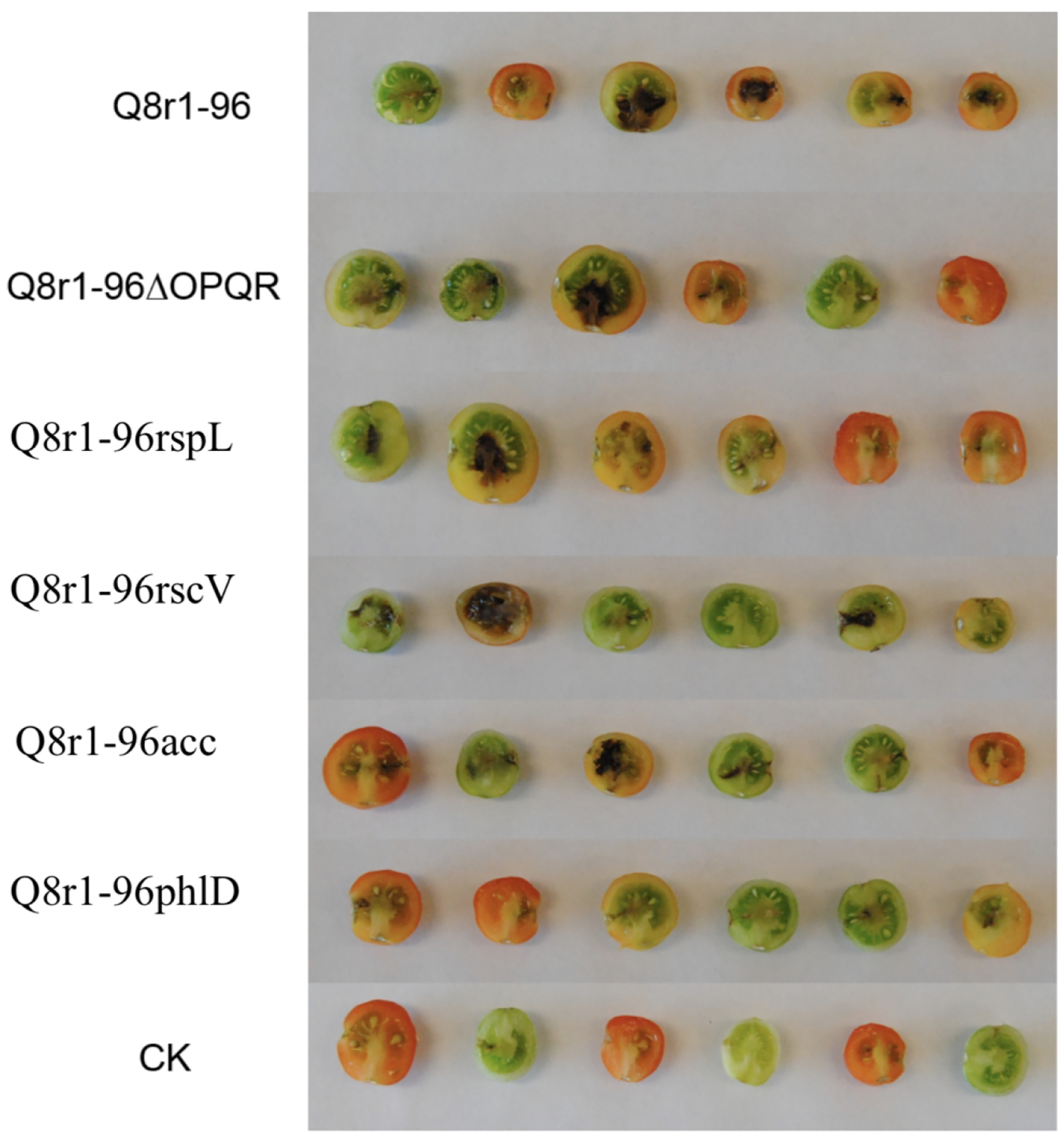

Fig. 1.

Cross sections of cherry tomato fruits (cv. Sweet 100) injected with strain Q8r1-96, DAPG or T3SS deficient mutants, or a recombinant strain suspended in sterile water with 0.85% NaCl at a dose of 108 CFU mL−1. Treatments included wild type Q8r1-96, Q8r1-96ΔOPQR, Q8r1-96rspL, Q8r1-96rscV, Q8r1-96acc, Q8r1-96phlD and 0.85% NaCl (control). Each treatment had six replicates with each fruit serving as a replicate. Fruits were green when injected and ten days after infection they were cut in half and rated for disease on a 0–3 scale.

TABLE 2.

Necrosis of tomato fruits inoculated with different doses of wild-type Q8r1-96, DAPG and T3SS deficient mutants, and an ACC deaminase recombinanta

| Doseb (CFU mL−1) | Q8r1-96 | Q8r1-96ΔOPQR | Q8r1-96rspL | Q8r1-96rscV | Q8r1-96acc | Q8r1-96phlD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 102 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 104 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 106 | 0.4±0.2 Ac | 0.2±0.2 A | 0.4±0.2 A | 0.2±0.2 A | 0.4±0.2 A | 0 A |

| 108 | 2.2±0.4 AB | 1.2±0.4 B | 1.6±0.4 B | 1.2±0.5 B | 2.4±0.2 A | 1.4±0.2 B |

Tissue necrosis was rated on a 0–3 scale at ten day after inoculation.

Each fruit was inoculated once with an aliquot of 10 μl.

Means ± SE in the same row followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P= 0.05 according to the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test.

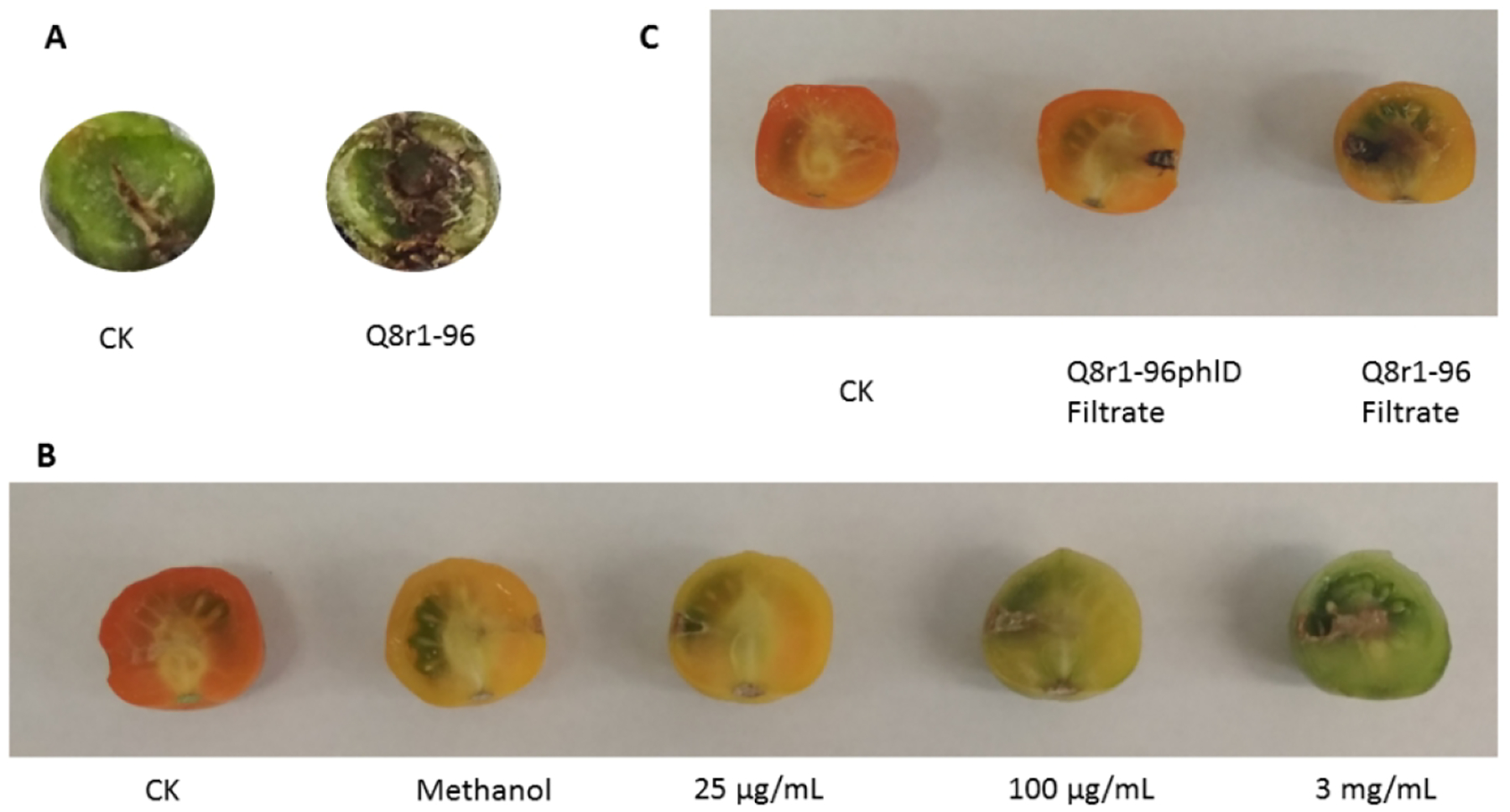

Koch’s postulates were completed on immature fruits attached to the vine. An initial inoculum dose of 107 CFU mL−1 of Q8r1-96 (105 CFU per wound) caused tissue necrosis and the population size of strain Q8r1-96 in fruits increased up to 200-fold at ten days after inoculation based on quantification by the PCR-based dilution-endpoint method. For example, in three separate fruits, population sizes increased to log 6.4, 7.2 and 7.3. Individual bacterial colonies were also isolated from diseased tissue by dilution plating on KMB+++Rif agar. Characteristic colonies of Q8r1-96 were selected from the plates, shown to be positive for phlD by PCR, injected into healthy immature fruits as described above, and disease again developed in the immature fruits. Finally, Q8r1-96 was again isolated from the fruits that developed symptoms (Supplementary Fig. S1). Strain Q8r1-96 also consistently caused necrosis in inoculated tomato stems (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Necrosis in a tomato stem following injection of strain Q8r1-96 (A); necrosis in detached tomato fruits following four injections of DAPG (B); necrosis in detached tomato fruits following four injections of cell-free filtrates of strains Q8r1-96 and Q8r1-96phlD (C).

Basis of the pathogenicity.

Derivatives of strain Q8r1-96 deficient in T3SS or DAPG were injected into detached tomato fruits. At doses below 106 CFU mL−1, the tested mutants behaved similarly to the wild-type Q8r1-96 and failed to produce necrosis symptoms in the fruits (Table 2). At higher doses, all tested mutants exhibited reduced ability to rot the fruits as compared to the wild type, but strain Q8r1-96phlD showed the most consistent loss in virulence (Table 3). Because Belimov et al. (2007) suggested that ACC deaminase may help mask the pathogenic properties of P. brassicacearum, we also included in our experiments strain Q8r1-96acc, which was engineered to express this enzyme constitutively. However, further tests revealed that Q8r1-96acc did not differ in virulence from the parent strain (Table 2, Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Necrosis of tomato fruits injected with strain Q8r1-96 and its mutants

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatmenta | Necrosis ratingb | Necrosis rating |

| Q8r1-96 | 2.5±0.2 Ac | 2.3±0.2 A |

| Q8r1-96ΔOPQR | 1.8±0.3 ABC | 0.8±0.2 B |

| Q8r1-96rspL | 1.5±0.2 BC | 2.2±0.2 A |

| Q8r1-96rscV | 2.0±0.3 AB | 0.8±0.2 B |

| Q8r1-96phlD | 1.0±0.3 C | 1.2±0.2 B |

Tomato fruits were injected once with a dose of 108 CFU mL−1.

Tissue necrosis was rated on a 0–3 scale at 10 days after inoculation.

Means ± SE in the same column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P= 0.05 according to the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test.

Cell-free culture filtrates of strains Q8r1-96 and Q8r1-96phlD were tested for ability to cause necrosis in detached tomatoes. Fruits injected only once or three times showed no necrosis, but fruits injected with filtrates four time (once on four consecutive days) developed symptoms similar to those caused by their source bacteria, Q8r1-96 and Q8r1-96phlD (Fig. 2C). Pure DAPG injected only once or three times did not cause necrosis typical of that caused by Q8r1-96, but injection of a dose of 25 μg mL−1 or greater for four times caused a necrosis similar to that caused by strain Q8r1-96. However, the methanol solvent used to dissolve the DAPG also darkened the tissue at the site of the injection, but it did not cause a collapse of the tissue like DAPG did. (Fig. 2B).

Because our experiments with Q8r1-96phlD implicated DAPG as a possible pathogenicity factor, we tested nine other genotypes of DAPG-producing pseudomonads and found that at concentrations of 107 or 108 CFU mL−1 all strains produced necrosis in detached immature tomato fruits, but the exact degree of damage varied among replicates and individual experiments (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Necrosis of tomato fruits injected with different genotypes of DAPG-producing Pseudomonas spp.

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Straina | Genotype | Necrosis ratingb | Necrosis rating |

| Q8r1-96 | D | 1.7±0.3 ABCc | 2.2±0.3 A |

| FFL1R22 | J | 1.7±0.3 ABC | 1.3±0.3 B |

| Pf-5 | A | 1.2±0.3 BC | 2.2±0.3 A |

| Q2–2 | E | 0.8±0.2 C | 1.8±0.2 AB |

| 1M1 | L | 1.7±0.3 ABC | 1.3±0.2 B |

| Q2–87 | B | 1.2±0.2 BC | 1.8±0.2 AB |

| JMP6 | F | 1.8±0.2 AB | 1.5±0.2 AB |

| D27B1 | M | 1.2±0.5 BC | 1.5±0.2 AB |

| STAD384 | C | 1.7±0.2 ABC | 1.3±0.4 B |

| FFL1R18 | G | 2.2±0.4 A | 2.2±0.3 A |

Tomato fruits were injected with a dose of 108 CFU mL−1.

Tissue necrosis was rated on a 0–3 scale.

Means ± SE in the same column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P= 0.05 according to the Kruskal-Wallis all-pairwise comparison test.

DISCUSSION

Our study was prompted by previous reports claiming that European strains of P. brassicacearum, such as Am3R and 520–1, are minor pathogens of tomato capable of causing either growth promotion or necrosis of fruits and stems in a dose-dependent manner (Belimov et al. 2007; Sikorski et al. 2001). We showed that strain Q8r1-96, isolated from wheat grown in the Quincy TAD soil and characteristic of P. brassicacearum isolates from PNW TAD soils caused disease in immature tomato fruits and stems with symptoms similar to those reported for strain Am3R (Belimov et al. 2007). In addition, P. brassicacearum strain L5.1–96 isolated from the well-described Lind, WA TAD soil also produced symptoms in tomato identical to those produced by strain Q8r1-96 (data not shown). It is important to note that phylogenetically, P. brassicacearum belongs to the P. corrugata subgroup of Pseudomonas (Almario et al. 2017) and P. corrugata naturally infects tomato, causing tomato pith necrosis (Scarlett et al. 1978). We are unaware of any example of P. brassicacearum naturally infecting tomato or causing disease. However, if natural infection did occur, the symptoms might be diagnosed as a mild infection by P. corrugata.

In general, strains of P. brassicacearum from around the world appear to have similar beneficial/deleterious characteristics in their relationship with plants. For example, strain P. brassicacearum 520–1 was first described by Sikorski et al. (2001) as a pathogen of tomato that caused chlorosis, browning, and necrotic lesions of infected plant wounds. Several P. brassicacearum strains from S. Australia exhibited take-all disease suppression in wheat infected with Gaeumannomyces graminis and were suggested to be potential biocontrol agents (Ross et al. 2000). P. brassicacearum strain Am3, besides its beneficial and deleterious activity on tomato, promoted root elongation of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) in vitro and increased root and shoot biomass of rape (B. napus) and pea (Pisum sativum) in pot trials (Belimov et al. 2001; Safronova et al. 2006). Endophytic strains of P. brassicacearum have been isolated from potato stem tissue infected with Pectobacterium carotovora (formerly Erwinia carotovora) (Reiter et al. 2003), but the pathogenicity or plant growth-promoting activity of these isolates was not reported.

P. brassicacearum strains such as Q8r1-96 and L5.1–96 also show both beneficial and deleterious effects on wheat that are dose and cultivar dependent (Yang et al. 2018). At low or moderate population levels these rhizobacteria are beneficial to the plant and protect against take-all (Schlatter et al. 2017) but higher densities they can be deleterious (Kwak et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2018). For example, a population of 105 CFU g−1 root of P. brassicacearum is the density needed for control of take-all (Raaijmakers and Weller 1998), and this dose applied to wheat seeds did not reduce the germination rate or root growth. However, greater bacterial doses caused necrosis of roots and stunting of wheat growth in a cultivar dependent manner (Yang et al. 2018). The effect is cultivar-dependent, as the wheat cultivar Buchanan was significantly more susceptible to the deleterious effects of strain Q8r1-96 than the cv. Tara (Yang et al. 2018).

One objective of our study was to determine the mechanism(s) of pathogenicity of P. brassicacearum strains from TAD soils. Using mutants of Q8r1-96 deficient in either T3SS or DAPG production, we showed that both significantly reduced the ability to rot tomato fruits as compared to the wild type, but the loss in virulence was consistent only with strain Q8r1-96phlD. Thus, we suggest that DAPG production is an important determinant of the pathogenicity of P. brassicacearum on tomato. This conclusion is also supported by results showing that cell-free culture filtrates of strain Q8r1-96 caused necrosis equivalent to the injected cells, but the necrosis caused by Q8r1-96phlD filtrates was much less. In addition, high doses of pure DAPG injected into fruits also caused necrosis. The role of DAPG in the necrosis is not surprising because using Q8r1-96phlD, Yang et al. (2018) demonstrated that DAPG production was primarily responsible for the phytotoxicity of Q8r1-96 on wheat cvs. Tara, Finley and Buchanan. DAPG is toxic to a broad spectrum of organisms (Keel et al. 1992; Weller et al. 2007). In plants, DAPG inhibits growth and seed germination (Keel et al. 1992; Maurhofer et al. 1995; Yang et al. 2018) and causes necrotic lesions on roots (Brazelton et al. 2008; Kwak et al. 2012), while DAPG is more active against dicots than monocots (Keel et al. 1992).

DAPG-producing fluorescent pseudomonads are in the P. fluorescens complex (Loper et al. 2012) and due to their genetic diversity were previously placed in 22 genotypes that were designated as A-T, PfY and PfZ (De La Fuente et al. 2006; Landa et al. 2006; Loper et al. 2012; McSpadden Gardener et al. 2000; Mavrodi et al. 2001; Schlatter et al. 2017). DAPG-producing pseudomonads have now been placed in six species in the P. fluorescens complex: P. protegens, P. kilonensis, P. gingeri, P. thivervalensis, P. brassicacearum and P. fluorescens (Almario et al. 2017; Loper et al. 2012; Vacheron et al. 2018); however, the P. fluorescens strains may be moved into one of the other five species (Almario et al. 2017). P. brassicacearum strains like Q8r1-96 and L5.1–96, previously called genotype D, share the ability to aggressively colonize wheat roots significantly better than do other DAPG producers (Landa et al. 2003; Raaijmakers and Weller, 2001).

Given the apparent role of DAPG in the pathogenicity of Q8r1-96, we tested strains representing nine other genotypes (A, B, C, E, F, G, J, L and M) isolated from fields throughout the U.S. and The Netherlands for ability to cause disease in tomato fruits. The finding that all these strains caused symptoms similar to those of Q8r1-96 suggests that pathogenicity in tomato is a common trait of DAPG-producing pseudomonads.

In conclusion, this study expands our understanding of the complexity of the biological activities of P. brassicacearum isolated from long-term wheat monoculture soils and the antibiotic that it produces. This bacterium and DAPG play many roles in nature: they are responsible for take-all decline in the PNW (Schlatter et al. 2017); they can be deleterious to wheat germination and root growth (Yang et al. 2018); they induce systemic resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana (Weller et al. 2012); and they can cause disease in tomato. Ultimately, the role that they play in nature will depend on the environment, plant genotype and bacterial dose or population size.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the O. A. Vogel Wheat Research Fund of Washington State University, Pullman, Washington U.S.A. M. Yang was supported by a scholarship from the China Scholarship Council (201806305044). Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Contributor Information

Mingming Yang, Department of Agronomy, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, P. R. China;.

Dmitri V. Mavrodi, School of Biological, Environmental, and Earth Sciences, The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406, USA;

Olga V. Mavrodi, School of Biological, Environmental, and Earth Sciences, The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406, USA;

Linda S. Thomashow, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Wheat Health, Genetics and Quality Research Unit, Pullman, WA 99164-6430, USA.

David M. Weller, U. S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Wheat Health, Genetics and Quality Research Unit, Pullman, WA 99164-6430, USA..

LITERATURE CITED

- Almario J, Bruto M, Vacheron J, Prigent-Combaret C, Moënne-Loccoz Y, and Muller D 2017. Distribution of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol biosynthetic genes among the Pseudomonas spp. reveals unexpected polyphyletism. Front. Microbiol 8:1218. doi: 10.3389/fmibc.2017.01218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankhead SB, Thomashow LS, and Weller DM 2016. Rhizosphere competence of wild-type and genetically engineered Pseudomonas brassicacearum is affected by the crop species. Phytopathology 106:554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangera MG, and Thomashow LS 1999. Identification and characterization of a gene cluster for synthesis of the polyketide antibiotic 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol from Pseudomonas fluorescens Q2–87. J. Bacteriol 181:3155–3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belimov AA, Dodd IC, Safronova VI, Hontzeas N, and Davies WJ 2007. Pseudomonas brassicacearum strain Am3 containing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase can show both pathogenic and growth-promoting properties in its interaction with tomato. J. Exp. Bot 58:1485–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belimov AA, Safronova VI, Sergeyeva TA, Egorova TN, Matveyeva VA, Tsyganov VE, Borisov AY, Tikhonovich IA, Kluge C, Preisfeld A, Dietz K-J, and Sepanok VV 2001. Characterization of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria isolated from polluted soils and containing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase. Can. J. Microbiol 47:642–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazelton JN, Pfeufer EE, Sweat TA, McSpadden Gardener BB, and Coenen C 2008. 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol alters plant root development. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 21:1349–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JJ, Schroth MN, Kominos SD, and Green SK 1975. Ornamental plants as carriers of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Phytopathology 65:425–431. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelis GR 2010. The type III secretion injectisome, a complex nanomachine for intracellular “toxin” delivery. Biol. Chem 391:745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente L, Mavrodi DV, Landa BB, Thomashow LS, and Weller DM 2006. phlD-based genetic diversity and detection of genotypes of 2,4-diacetylpholorogucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol 56:64–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson O, O’Gara F, and Morrissey JP 2010. The Pseudomonas fluorescens secondary metabolite 2,4 diacetylphloroglucinol impairs mitochondrial function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 97:261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick BR 1995. The enhancement of plant growth by free-living bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol 41:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Haas D, and Keel C 2003. Regulation of antibiotic production in root-colonizing Pseudomonas spp. and relevance for biological control of plant disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 41:117–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House BL, Mortimer MW, and Kahn ML 2004. New recombination methods for Sinorhizobium meliloti genetics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 70:2806–2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel C, Schnider U, Maurhofer M, Voisard C, Laville J, Burger U, Wirthner P, Haas D, and Défago G 1992. Suppression of root diseases by Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0: importance of the bacterial secondary metabolite 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 5:4–13. [Google Scholar]

- King EO, Ward MK, and Raney DE 1954. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J. Lab. Clin. Med 44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak YS, Bonsall RF, Okubara PA, Paulitz TC, Thomashow LS, and Weller DM 2012. Factors impacting the activity of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens against take-all of wheat. Soil Biol. Biochem 54:48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak YS, Han S, Thomashow LS, Rice JT, Paulitz TC, Kim D, and Weller DM 2011. Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome-wide mutant screen for sensitivity to 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol, an antibiotic produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 77:1770–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa BB, Mavrodi DV, Thomashow LS, and Weller DM 2003. Interactions between strains of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens in the rhizosphere of wheat. Phytopathology 93:982–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa BB, Mavrodi OV, Schroeder KL, Allende-Molar R, and Weller DM 2006. Enrichment and genotypic diversity of phlD-containing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. in two soils after a century of wheat and flax monoculture. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol 55:351–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loper JE, Hassan KA, Mavrodi DV, Davis EW, Lim CK, Shaffer BT, Elbourne LDH, Stockwell VO, Hartney SL, Breakwell K, Henkels MD, Tetu SG, Rangel LI, Kidarsa TA, Wilson NL, van Mortel J, Song C, Blumhagen R, Radune D, Hostetler JB, Brinkac LM, Durkin SA, Kluepfel DA, Wechter PW, Anderson AJ, Kim YC, Pierson LS, Pierson EA, Lindow SE, Raaijmakers JM, Weller DM, Thomashow LS, Allen AE, and Paulsen IT 2012. Comparative genomics of plant-associated Pseudomonas spp: insights into diversity and inheritance of traits involved in multitrophic interactions. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurhofer M, Keel C, Haas D, and Défago G 1995. Influence of plant species on disease suppression by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain CHA0 with enhanced antibiotic production. Plant Pathol. 44:40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrodi DV, Joe A, Mavrodi OV, Hassan KA, Weller DM, Paulsen IT, Loper JE, Alfano JR, Thomashow LS 2011. Structural and functional analysis of the type III secretion system from Pseudomonas fluorescens Q8r1-96. J. Bacteriol 193:177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrodi OW, Mavrodi DV, Parejko JA, Thomashow LS, and Weller DM 2012. Irrigation differentially impacts populations of indigenous antibiotic-producing Pseudomonas spp. in the rhizosphere of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 78:3214–3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavrodi OV, McSpadden Gardener BB, Mavrodi DV, Bonsall RF, Weller DM, and Thomashow LS 2001. Genetic diversity of phlD from 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas species. Phytopathology 91:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSpadden Gardener BB, Schroeder KL, Kalloger SE, Raaijmakers JM, Thomashow LS, and Weller DM 2000. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of phlD-containing Pseudomonas isolated from the rhizosphere of wheat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 66:1939–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers JM, and Weller DM 1998. Natural plant protection by 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas spp. in take-all decline soils. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact 11:144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers JM, and Weller DM 2001. Exploiting the genetic diversity of Pseudomonas spp: characterization of superior colonizing P. fluorescens strain Q8r1-96. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 67:2545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter B, Wermbter N, Gyamfi S, Schwab H, and Sessitsch A 2003. Endophytic Pseudomonas spp. populations of pathogen-infected potato plants analysed by 16S rDNA- and 16S rRNA-based denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Plant Soil 257:397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Ross IL, Alami Y, Harvey PR, Achouak W, and Ryder MH 2000. Genetic diversity and biological control activity of novel species of closely related pseudomonads isolated from wheat field soils in South Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 66:1609–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safronova VI, Stepanok VV, Engqvist GL, Alekseyev YV, and Belimov AA 2006. Root-associated bacteria containing 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate deaminase improve growth and nutrient uptake by pea genotypes cultivated in cadmium supplemented soil. Biol. Fert. Soils 42:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Scarlett CM, Fletcher JT, Roberts P, and Lelliott RA 1978. Tomato pith necrosis caused by Pseudomonas corrugate n. sp. Ann. Appl. Biol 88:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Schlatter D, Kinkel L, Thomashow SL, Weller MD, and Paulitz T 2017. Disease suppressive soils: New insights from the soil microbiome. Phytopathology 107:1284–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski J, Jahr H and Wackernagel W 2001. The structure of a local population of phytopathogenic Pseudomonas brassicacearum from agricultural soil indicates development under purifying selection pressure. Environ. Microbiol 3:176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tampakaki AP 2014. Commonalities and differences of T3SSs in rhizobia and plant pathogenic bacteria. Front. Plant Sci 5:1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troppens DM, Dmitriev RI, Papkovsky DB, O’Gara F, and Morrissey JP 2013. Genome-wide investigation of cellular targets and mode of action of the antifungal bacterial metabolite 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 13:322–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacheron J, Desbrosses G, Renoud S, Padilla R, Walker V, Muller D, and Prigent-Combaret C 2018. Differential contribution of plant-beneficial functions from Pseudomonas kilonensis F113 to root system architecture alterations in Arabidopsis thaliana and Zea mays. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact 31:212–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller DM, Landa BB, Mavrodi OV, Schroeder KL, De La Fuente L, Bankhead SB, Allende-Molar R, Bonsall RF, Mavrodi DV, and Thomashow LS 2007. Role of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. in the defense of plant roots. Plant Biol. 9:4–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller DM, Mavrodi DV, van Pelt JA, Pieterse CM, van Loon LC, and Bakker PAHM 2012. Induced systemic resistance (ISR) in Arabidopsis thaliana against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato by 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas fluorescens. Phytopathology 102:403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, and Cao Y 2012. Biosynthesis of phloroglucinol compounds in microorganisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 93:487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MM, Mavrodi DV, Mavrodi OV, Bonsall RF, Parejko JA, Paulitz TC, Thomashow LS, Yang HT, Weller MD, and Guo JH 2011. Biological control of take-all by fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. from Chinese wheat fields. Phytopathology 101:1481–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MM, Mavrodi DV, Thomashow SL, and Weller MD 2018. Differential response of wheat cultivars to Pseudomonas brassicacearum and take-all decline soil. Phytopathology 108:1363–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.