Graphic abstract

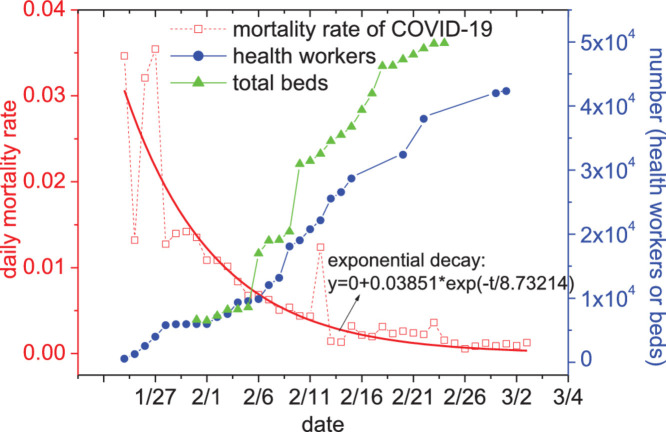

The 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) outbreak caused by SARS-CoV-2 is on-going in China and has hit many countries.1, 2, 3 As of 3 March 2020, there have been 80,270 confirmed cases and 2981 deaths in China, most of which are from the epicenter of the outbreak, Wuhan City, the capital of Hubei Province. New COVID-19 cases have been steadily declining in

China and more than 60,000 patients have been recovered,4 largely due to the effective implementation of comprehensive control measures in China.5 , 6 Here we report that some of these measures, such as a dramatic and timely increase of medical supplies, may play a critical role such that the mortality and recovery rates of COVID-19 in Wuhan follow exponential decay and growth modes, respectively.

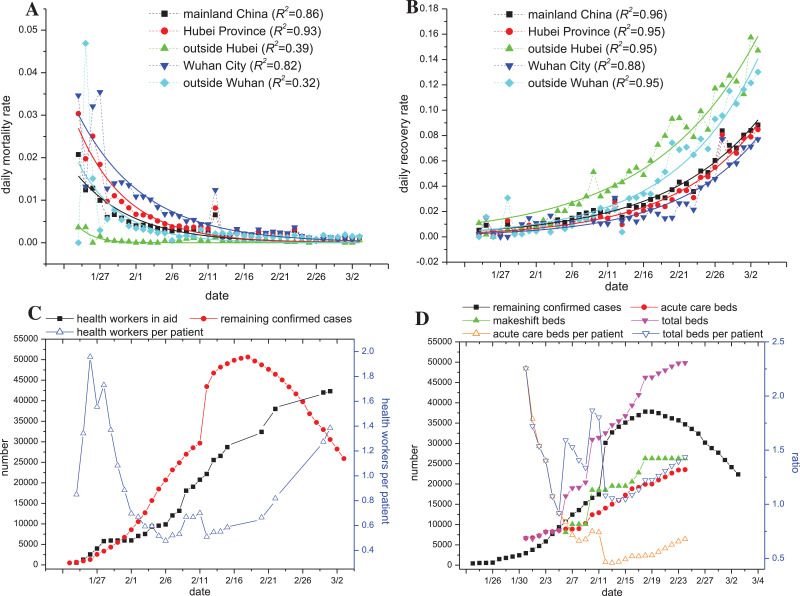

We collected data for analysis on the officially released cumulative numbers of confirmed, dead and recovered cases (from 23 Jan to 3 Mar 2020) in five geographic regions, i.e., mainland China, Hubei Province, outside Hubei (in China), Wuhan City and outside Wuhan (in Hubei). As of 3 Mar 2020, crude fatality ratios (CFRs) in the above regions are 0.027±0.006, 0.035±0.007, 0.005±0.002, 0.045±0.012 and 0.021±0.008, respectively, in line with earlier reports.5 , 6 While the mortality rates of COVID-19 outside Hubei and outside Wuhan appear constant over time, the mortality rates in Hubei and Wuhan decline continuously (Fig. 1 (A)). Strikingly, the mortality rates in Hubei and Wuhan are well-fitted with the exponential decay mode (R2 being 0.93 and 0.82, respectively; Fig. 1(A) and Table S1), and it is the same forth with that in China (R2 being 0.86) but not with that outside Hubei and outside Wuhan (R2 being 0.39 and 0.32, respectively). Remarkably, we found that the recovery rates of COVID-19 patients in the above regions were all well-fitted with the exponential growth mode (R2 being 0.96, 0.95, 0.95, 0.88 and 0.95, respectively; Fig. 1(B) and Table S1). Such intriguing pattern for the COVID-19 mortality and recovery rates in Wuhan (or Hubei) somehow contradicts traditional epidemiological models wherein both are assumed as constants.7

Fig. 1.

Fitting the COVID-19 mortality and recovery rates with exponential decay and growth functions, respectively and timely supply of medical resources. (A, B) Mortality rate (panel A) and recovery rate (panel B) for COVID-19 in China over time and by location, with exponential decay- and growth-based regression analyses being performed, respectively (as shown by colored solid lines). Parameters from the regression analyses are shown in Table S1, with R2 being shown here. (C) Numbers of the aided health workers in Hubei over time. Ratio of the aided health workers to patients was also plotted (note: most of the aided health workers are working in Wuhan; refer to Table S3). (D) Numbers of the remaining confirmed cases of COVID-19, and acute care beds, makeshift beds from Fangcang hospitals and total beds in Wuhan over time. Ratio of beds to patients was also plotted. Here the data of newly supplied beds in Hubei are not available and thus the data for Wuhan were analyzed.

The above unique pattern may reflect the fact that COVID-19 patients in Wuhan (or Hubei) have been treated more effectively day by day. Here we focused on two components essential for effective treatments, i.e., the supply of health workers and hospital beds. As a matter of fact, a great number (up to 42,000, as of 1 March 2020) of health workers have been aided by other provinces in China (Table S2) and they are working in different cities of Hubei (Table S3). This extraordinary aid keeps the ratio of the health workers to patients in Hubei at above 0.6 despite the number of remaining confirmed cases has ten-fold increased up to 50,000 on 18 Feb (Fig. 1(C)). Results also show that the number of acute care beds from more than 45 designated hospitals plus two newly built ones in Wuhan has been consecutively increasing up to 23,532 (as of Feb 24) under the government-directed re-allocation (Fig. 1(D)). This supply thus enabled the severe and critical patients to be treated timely and effectively.6 More importantly, there have been over 10 temporary hospitals (named Fangcang hospitals) reconstructed from gymnasium and exhibition centers, which provide more than 26 000 makeshift beds for mild patients (Fig. 1(D)). These combinations guaranteed nearly 100% of COVID-19 patients to be treated in hospitals even if the number of remaining confirmed cases has ten-fold increased up to 38 000 on 18 Feb (Fig. 1(D)). In contrast, a lot of patients had to stay at home in the early stage of the outbreak in Wuhan due to the shortage of beds such that many transmissions in households occurred.6

Accordingly, the effective implementation of comprehensive control measures and infection-treatment practices is critical for combatting any new pathogens, not only interrupting the transmissions but also saving the patients. Timely supplied medical resources, including re-allocation of acute care beds, rapid construction of new hospitals and generous aid of health workers by other less-severe areas, apparently help the epicenter of the outbreak Hubei (Wuhan) to accomplish a unique and also encouraging outcome for life-saving such that the mortality and recovery rates of nearly 50,000 COVID-19 patients exponentially decays and grows, respectively. Other crucial factors contributing to this success may include the improved and optimized diagnosis and treatment strategies,8 which are critical for saving severe and critical patients.5 , 6 , 9 This speculation appears to be supported by the exponential growth of the COVID-19 recovery rate outside Hubei (Fig. 1(B)) where medical resources are relatively sufficient over time.10 Collectively, the achievement made in Hubei (or Wuhan) may provide useful guidance for many countries to be better prepared for the potential pandemic2 that may overwhelm local health care systems.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work is support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31972918 and 31770830 to XF). All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.018.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Tang J.W., Tambyah P.A., Hui D.S.C. Emergence of a novel coronavirus causing respiratory illness from Wuhan, China. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. visited on 4 March, 2020.

- 3.Zhou P. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The National Health Commission of China, real-time data of the COVID-19 outbreaks in China (in Chinese), http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/gzbd_index.shtml. accessed on 4 March, 2020.

- 5.The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. Vital surveillances: the epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020, http://weekly.chinacdc.cn/en/article/id/e53946e2-c6c4-41e9-9a9b-fea8db1a8f51, in China CDC Weekly. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Report of the WHO – China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf. 2020.

- 7.Wang X.S., Wu J., Yang Y. Richards model revisited: validation by and application to infection dynamics. J Theor Biol. 2012;313:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The National Health Commission of China, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) diagnosis and treatment plan (in Chinese, 7th version). Available from:http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989.shtml., visited on 5 March, 2020.

- 9.Yang X. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji Y. Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and healthcare resource availability. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30068-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.