Abstract

Background

Approximately 15% to 25% of all hospitalised patients have indwelling urethral catheters, mainly to assist clinicians to accurately monitor urine output during acute illness or following surgery, to treat urinary retention, and for investigative purposes.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine the best strategies for the removal of catheters from patients with a short‐term indwelling urethral catheter. The main outcome of interest was the number of patients who required recatheterisation following removal of indwelling urethral catheter.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Group Specialised Register (searched 7 December 2005), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 2), MEDLINE (January 1966 to 12 July 2006), EMBASE (January 1980 to 12 July 2006), CINAHL (January 1982 to 12 July 2006), Nursing Collection (January 1995 to January 2002) and reference lists of relevant articles and conference proceedings were searched. We also contacted manufacturers and researchers in the field. No language or other restrictions were applied.

Selection criteria

All randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the effects of alternative strategies for removal of short‐term indwelling urethral catheters on patient outcomes were considered for inclusion in the review.

Data collection and analysis

Eligibility of the trials for inclusion in the review, details of eligible trials and the methodological quality of the trials were assessed independently by two reviewers. Relative risks (RR) for dichotomous data and a weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous data were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where synthesis was inappropriate, trials were considered separately.

Main results

Twenty six trials involving a total of 2933 participants were included in the review. One trial included three treatment groups.

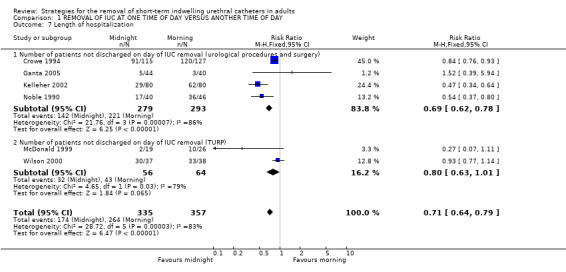

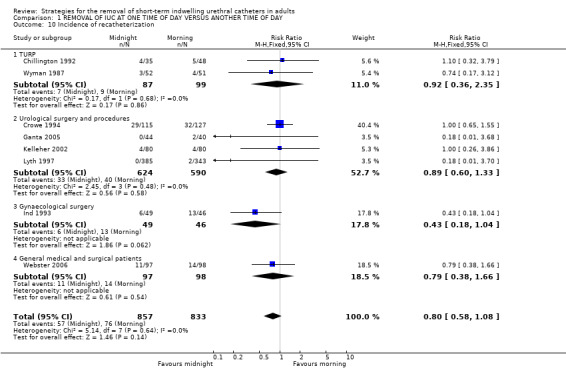

In 11 RCTs amongst 1389 people, there was no significant difference in need for recatheterisation, although recatheterisation after removal at night was more likely to be during working hours. Pooled results demonstrated that, following urological surgery and procedures, patients whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed at midnight passed significantly larger volumes at their first void (Difference (fixed) 96 ml; 95% CI 62 to 130). Similar findings were reported for patients following TURP (Difference (fixed) 27; 95% CI 23 to 31). Removal at midnight was also associated with longer time to first void, and shorter lengths of hospitalisation (relative risk of not going home on day of removal = 0.71, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.79).

Results in 13 trials amongst 1422 participants having early rather than delayed catheter removal were consistent with a higher risk of voiding problems and a lower risk of infection, with shorter hospitalisation.

In three trials involving 234 participants the data were too few to assess differential effects of catheter clamping compared with free drainage prior to withdrawal. No eligible trials compared flexible with fixed duration of catheterisation, or assessed prophylactic alpha sympathetic blocker drugs prior to catheter removal.

Authors' conclusions

There is suggestive but inconclusive evidence of a benefit from midnight removal of the indwelling urethral catheter. There are resource implications but the magnitude of these is not clear from the trials. The evidence also suggests shorter hospital stay after early rather than delayed catheter removal but the effects on other outcomes are unclear. There is little evidence on which to judge other aspects of management, such as catheter clamping.

Plain language summary

Strategies for removing catheters used in the short term to drain urine from the bladder in hospitalised patients

Patients in hospital with a brief severe illness or following surgery may have a tube placed into the passage from the bladder (an in‐dwelling urethral catheter). Potential complications are infection, tissue damage and patient discomfort. This review identified 26 controlled trials looking at the best strategies for removal of catheters. In 11 studies comparing late night versus early morning removal, removal at midnight resulted in a longer time to first void and patients passing significantly larger volumes, although these findings varied widely. There was no apparent effect on the number of patients who required recatheterisation because of subsequent urinary retention, but patients with catheters removed at midnight were discharged from hospital significantly earlier than those with morning removal. Based on findings from 13 trials, limiting how long a catheter was left in place was linked to a shorter stay in hospital and less risk of infection. The information available from three trials was too limited to assess whether clamping prior to removal, to simulate normal filling of the bladder, improved outcomes.

Background

Approximately 15% to 25% of all patients admitted to hospital are catheterised to monitor urine output during acute illness or following surgery, or to treat urinary retention, or for investigative purposes (Dunn 2000). Short‐term use of an indwelling urethral catheter is a safe and effective strategy in the maintenance of bladder and renal health and judicious use contributes to improved outcomes. However, insertion of an indwelling urethral catheter is not without the risk of complications. Catheter associated bacteriuria is common and increases by 5 to 8% each day during the period of catheterisation (Getliffe 1996). Other complications include structural damage to the urinary tract, bleeding, creating a false passage, and patient discomfort (Crowe 1994). Retention of urine has also been reported as a common problem following the removal of indwelling urethral catheters (Crowe 1994). This is associated with a risk of over distension and permanent detrusor muscle damage (Rosseland 2002) which can occur from 7 to 48 hours after removal (Wyman 1987).

While there is extensive literature on the type, maintenance, and techniques for insertion of urinary catheters, limited attention has been given to the policies and procedures for their removal. Although the insertion, removal and management of the catheter is usually undertaken by nurses, decisions about the removal of the catheter often remain with the medical practitioner. While the importance of short‐term urethral catheter management is recognised, there is no consensus among clinicians about the optimal time and the method for removal of indwelling urethral catheters. Policies are likely to be based on personal preference and established practices (Irani 1995) rather than on research evidence. While clinicians have established policies, there has been no objective and systematic examination of the effect of the time of day the catheter is removed, the length of time the catheter is left in place, or if clamping the catheter prior to removal influences patient outcomes.

One argument for removal of the catheter in the early morning (Blandy 1989; Crowe 1994) is that reduced staff at night might fail to respond to complications, such as urinary retention, that can develop following the removal of the catheter (Blandy 1989). Other suggested benefits of removal of the catheter in the early morning include allowing the patient to rest through the night, and then to adjust back to their normal voiding pattern during the day (Crowe 1994).

The justification for removal of the catheters at midnight is that people tend to void on waking in the morning (Chillington 1992). Therefore removal of indwelling urethral catheters at midnight enables urinary retention and other complications to be detected early in the day and treated during working hours when there is access to resources and services (Chillington 1992). Researchers have also reported that patients whose catheters were removed in the night had larger volumes at first void compared to other people whose catheters were removed in the morning (Chillington 1992; Noble 1990). It has been suggested that the timing of catheter removal may affect a patient's length of stay in hospital with consequent resource implications. In one study it was found that removal of catheters at midnight resulted in patients being discharged a mean of 0.7 days earlier than patients whose catheters were removed in the morning (Chillington 1992) thus resulting in economic benefits related to shorter length of hospitalisation and efficient discharge planning.

There is also debate about whether flexible policies are better than relatively fixed policies for catheter removal (Wyman 1987). Practice is known to vary. For example, local clinical audits for catheter removal have indicated that 49% of catheters are removed either at the discretion of the nurse or at the time of the medical rounds, and only 34% were removed at midnight (Watt 1998). Of those indwelling urethral catheters that were scheduled for removal in the morning, only 70% were removed on time (Noble 1990; Watt 1998).

Practice also varies with respect to the length of time the catheter is left in situ and the procedure for its removal. Factors influencing these decisions include clinician preference, patient tolerance and the reasons for the insertion of the catheter. Historically, the removal of indwelling urethral catheters has occurred 24 to 72 hours following vaginal surgery (Guzman 1994), 3 to 5 days following transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) (Mamo 1991), 12 to 14 days following perineal prostatectomy, and 10 days following abdominoperineal resection (APR) (Oberst 1981). Timing may affect length of hospital stay. For example, in paediatric patients undergoing ureteroneocystostomy, removal of the indwelling urethral catheter within 24 hours following surgery resulted in a statistically significant decrease in the length of hospital stay when compared to removal of the indwelling urethral catheter after 24 hours (Gonzalez 1998). Recent literature advocates early removal of the catheters, particularly after TURP. Too early removal after radical prostatectomy may, however, lead to complications such as haematuria leading to clot formation and anastomotic urinary extravasation possibly resulting in urinoma formation and pelvic abscess (Little 1995).

Bladder dysfunction and postoperative voiding impairment have been documented following catheterisation and these can lead to infections of the urinary tract (Oberst 1981). The intermittent clamping of the indwelling urethral catheter draining tube prior to withdrawal has been suggested on the basis that this simulates normal filling and emptying of the bladder (Roe 1990). While clamping catheters might minimise postoperative neurogenic urinary dysfunction, it could also result in bladder infection or distension if the clamps are not released as scheduled (Roe 1990).

Another strategy practiced prior to removal of urethral catheters is the use of alpha adrenergic blocker drugs. It has been reported that alpha blockers are effective in the treatment of voiding dysfunction by enhancing detrusor contractility and lowering urethral resistance in patients with underactive bladder (Yamanishi 2004).

To date, the literature relating to the policies for the removal of indwelling urethral catheters has not been evaluated in a manner that will enable clinicians to develop evidence‐based policies for practice. This systematic review summarised the evidence from randomised controlled trials related to alternative approaches to the removal of short‐term indwelling urethral catheters.

Objectives

The objective of this review was to determine the best strategies for the removal of catheters from patients with a short‐term indwelling urethral catheter.

The following comparisons were made: (1) removal of the catheter at one time of the day versus at another time (eg at 0600 to 0800 hours versus 2200 to 2400 hours); (2) removal after a shorter duration of catheter use versus after a longer duration, as defined by trialists; (3) removal after a flexible duration of catheter use versus after a fixed duration; (4) removal of a catheter after a period of clamp and release versus removal of a free‐draining catheter; (5) removal of a catheter using prophylactic alpha adrenergic blocker drugs versus removal without drug treatment.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials evaluating the effects of practices undertaken for the removal of short‐term indwelling urethral catheters were included in the review.

This review excluded trials that involved suprapubic catheters, intermittent catheterisation and removal of nephrostomy and suprapubic tubes.

Types of participants

People of all ages having a short‐term indwelling urethral catheter, in any setting (hospital, community, nursing home) were included in the review. For the purpose of this review a short‐term indwelling catheter was defined as a catheter inserted for a period of 1 to 14 days (Dunn 2000). Participants with congenital abnormalities of the genitourinary system were excluded from the review.

Types of interventions

All the following removal policies were eligible for inclusion in the review: (1) differing timings of removal of the indwelling urethral catheter, eg early (at 0600 to 0800 hours) or late (at 2200 to 2400 hours); (2) differing durations of catheterisation prior to removal of an indwelling urethral catheter; (3) free draining or clamping and release of the indwelling urethral catheter; (4) use of alpha blocker drugs as an adjunct to catheter removal.

Types of outcome measures

The main outcome of interest was the number of participants who required recatheterisation following removal of indwelling urethral catheter.

Other outcomes assessed included:

Clinicians' observations

Time to first void

Volume of first void

Length of hospitalisation

Incidence of urinary retention

Patients' observations

Patient comfort

Patient satisfaction

Quality of life

Generic QoL measures eg Short Form 36 (Ware 1992)

Psychological outcome measures eg Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond 1983

Complications/adverse effects

Other complications of catheterisation (or recatheterisation)

Incidence of urinary tract infection

‐ asymptomatic bacteriuria ‐ symptomatic urinary tract infections ‐ use of antibiotics

Other adverse effects of an intervention

Economic outcomes

Cost effectiveness

Resource use

Any other non‐prespecified outcomes judged to be important when performing the review.

Search methods for identification of studies

This review has drawn on the search strategy developed for the Incontinence Review Group. Relevant trials were identified from the Incontinence Group Specialised Register of controlled trials which is described under the Incontinence Group's details in The Cochrane Library (For more details please see the ‘Specialized Register’ section of the Group’s module in The Cochrane Library). The register contains trials identified from MEDLINE, CINAHL, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings.

The Incontinence Group Specialised Trials Register was searched using the Group's own keyword system, the search terms used were: ({design.cct*} OR {design.rct*}) AND {topic.mech.cath*} (All searches were of the keyword field of Reference Manager 9.5 N, ISI ResearchSoft).

Date of the most recent search of the register for this review: 7 December 2005. The trials in the Incontinence Group Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL.

For this review extra specific searches were performed by the reviewers ‐ aimed at locating trials related to midnight versus morning removal of short term indwelling urethral catheters. Brief details are given below and a fuller description including the search terms used can be found in Appendix 1.

We did not impose any language or other limits on any of the searches.

Electronic searches

Electronic bibliographic databases The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched.

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 2), (on web, Update Software site, via OVID in July 2006)

MEDLINE (via OVID) (years searched: January 1966 to 12 July 2006)

EMBASE (years searched: January 1980 to 12 July 2006)

CINAHL (years searched: January 1982 to 12 July 2006)

Nursing Collection Journals @ OVID (years searched: January 1995 to January 2002)

Searching other resources

Conference Proceedings The following conference proceedings were scanned briefly:

International Continence Society (ICS), Annual Meeting (1995 to 2000 inclusive);

International Urogynecological Association (IUGA), Annual Meeting (2000 and 2001);

Hong Kong Urological Association, Annual Meeting (1995 to 2001 inclusive).

Other Sources The reference lists of relevant articles were searched for other possible relevant trials. Manufacturers, researchers and experts in the field were contacted to ask for other possibly relevant trials, published or unpublished.

Data collection and analysis

The references and abstracts identified from the search were independently assessed against the inclusion/exclusion criteria by two review authors and the full text obtained of potentially relevant reports. If the title and abstract were inconclusive full text were obtained for further assessment. Trials that had been reported in more than one publication were included only once. Decisions about study eligibility were reached by consensus.

The methodological quality of the eligible randomised controlled trials was assessed independently by two review authors using the quality assessment tool as described in the Incontinence Group module (Grant 2002). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third person. Each study was critically appraised and the methodological quality was assessed using the following checklist: (1) detailed description of inclusion and exclusion criteria used to obtain the sample; (2) evidence of allocation concealment at randomisation; (3) the validity of methods of outcome assessment; (4) description of withdrawals and dropouts; (5) the potential for bias in outcome assessment. Data extraction from the included trials was undertaken and summarised independently by two review authors using a data extraction tool that was developed for the review. The data extraction tool was piloted by three independent reviewers prior to use. Discrepancies between review authors were resolved by discussion. Data were collected relating to: (a) patient demographics; (b) patient inclusion/exclusion criteria; (c) types (eg different shapes, lengths, sizes) of short‐term indwelling catheters; (d) types of operation categories; (e) description of the interventions; (f) description of the outcomes; (g) prespecified outcomes (volume of the first void , time to first void, length of hospitalisation, incidence of urinary retention and recatheterisation, urinary tract infection, time of day recatheterised, urethral pain and discharge, secondary haemorrhage, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), epididymitis, recurrence of strictures cost effectiveness and patient satisfaction) (h) follow‐up period; (i) the number and reasons for withdrawals and dropouts. Attempts were made to obtain missing data by contacting the authors.

Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Higgins 2005).

The trials were assessed for clinical heterogeneity by considering the settings, populations, interventions and outcomes. Based on this, a decision was taken about whether or not it was appropriate to combine the data. As a general rule, a fixed effect model was used to combine data in meta‐analyses. Consideration was given to using a random effects model if there was significant statistical heterogeneity (as judged by the chi square or I² test) that could not be explained by differences in the characteristics of included studies, or the data were not summarised.

Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for dichotomous data. Analysis of continuous data was undertaken using the mean and standard deviation (SD) values to derive weighted mean differences (WMD) and their 95% CIs. Where actual P values obtained from t‐tests were quoted, standard deviations were extracted by first obtaining the corresponding t‐value from a table of the t‐distribution (noting that the degrees of freedom are given by NE [sample size in the experimental group] plus NC [sample size in the control group] minus 2). The standard error of the difference in means was obtained by dividing the mean difference by the t‐value. Using this data, a treatment effect estimate was calculated based upon the generic inverse variance (GIV). Due to the paucity of data, sensitivity analyses could not be undertaken. Where synthesis was inappropriate, individual trials were considered separately.

Planned subgroup analyses were undertaken to consider differences between the sexes and reasons for catheterisations. In addition, subgroup/sensitivity analysis by different catheter sizes was planned but could not be undertaken due to the absence of data to allow this analysis. All calculations were made using the Cochrane statistical package Review Manager (RevMan) Version 4.2.

Results

Description of studies

Twenty‐six trials (eight new) involving a total of 2933 participants were included in this first update of the review. One trial (Guzman 1994) included three treatment groups. Eleven (three new) compared late night versus early morning removal of catheters (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ganta 2005; Ind 1993; Kelleher 2002; Lyth 1997; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Webster 2006; Wilson 2000; Wyman 1987); thirteen (five new) compared various durations of catheterisation (Benoist 1999; Dunn 2003; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Hansen 1984; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; Lau 2004; Nielson 1985; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004; Taube 1989; Toscano 2001); and three (Guzman 1994; Oberst 1981; Williamson 1982) compared clamping to free drainage.

A further three studies are awaiting translation (Alonzo‐Sonsa 1997; Christensen 1983; Efimenko 2004).

Sample sizes

The number of participants for trials comparing time of removal ranged from 48 (McDonald 1999) to 282 (Crowe 1994), with a total of 1389 participants in the studies. One thousand three hundred and sixteen participants were included in trials comparing duration of catheterisation, with the number in individual trials ranging from 40 (Nielson 1985) to 250 (Dunn 2003). In the trials comparing clamping versus free drainage, the number of participants ranged from 8 (Williamson 1982) to 120 (Oberst 1981).

The protocol used for removal of catheters was not described in any trial. Seven trials (Dunn 2003; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Nielson 1985; Sun 2004; Toscano 2001; Wyman 1987) identified the type of indwelling urethral catheter used, and five trials (Chillington 1992; Ind 1993; Lyth 1997; Noble 1990; Wilson 2000) stated that the indwelling urethral catheters were removed by nurses.

Gender

Eight trials included participants of both genders (Benoist 1999; Crowe 1994; Kelleher 2002; Lau 2004; Lyth 1997; Noble 1990; Oberst 1981; Webster 2006); eight involved men alone (Chillington 1992; Ganta 2005; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; McDonald 1999; Taube 1989; Toscano 2001;Wyman 1987); seven trials included only women (Dunn 2003; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Ind 1993; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004; Williamson 1982); and in two trials the gender of the participants was unclear (Hansen 1984; Nielson 1985). The ages of the participants included in the trials ranged between 15 and 87 years.

Reasons for catheterisation

The reasons for catheterisation varied between the trials:

following TURP only (Chillington 1992; Ganta 2005; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; Lyth 1997; McDonald 1999; Toscano 2001; Wilson 2000; Wyman 1987);

following various urological procedures and surgery that included TURP, transurethral resection of a bladder tumour, trial of void, cystoscopy, ureteroscopy, lithotripsy, lithopexy, pyeloplasty, bladder neck incision, clot retention, urethrotomy, percutaneous colposuspension and general postoperative surgery (Crowe 1994; Kelleher 2002; Noble 1990);

following gynaecological surgery that included hysterectomy (radical, extended, total abdominal, vaginal), posterior exenteration, anterior colporrhaphy, Manchester repair, vulvectomy, radical oophorectomy, ovarian cystectomy, myomectomy and adhesiolysis (Dunn 2003;Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Ind 1993; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004; Webster 2006; Williamson 1982);

after rectal resection (Benoist 1999);

following urethrotomy (Hansen 1984; Nielson 1985);

after abdominoperineal resection (Oberst 1981);

in the management of acute urinary retention (Lau 2004; Taube 1989).

Intervention details

The protocol used for removal of catheters was not described in any trial. Seven trials (Dunn 2003; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Nielson 1985; Sun 2004; Toscano 2001; Wyman 1987) identified the type of indwelling urethral catheter used, and five trials (Chillington 1992; Ind 1993; Lyth 1997; Noble 1990; Wilson 2000) stated that the indwelling urethral catheters were removed by nurses.

Baseline comparability of groups

Data on baseline comparability were presented relating to:

age (Benoist 1999; Dunn 2003; Chillington 1992; Ganta 2005; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Ind 1993; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; McDonald 1999; Nielson 1985; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004; Toscano 2001; Webster 2006; Wyman 1987);

duration of catheterisation (Webster 2006; Wyman 1987);

operations performed (Dunn 2003; Hakvoort 2004; Guzman 1994; Ind 1993; Irani 1995; Kelleher 2002; Sun 2004; Webster 2006);

prostatic size and histology (Chillington 1992; Koh 1994; McDonald 1999; Toscano 2001);

aetiology and severity of strictures (Hansen 1984; Nielson 1985);

history of previous incontinence procedures (Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004; Webster 2006), and

reasons for catheterisation (Crowe 1994; Dunn 2003; Sun 2004; Webster 2006).

All trials indicated that there was baseline comparability between the groups. For further descriptions see Table of Included Studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the trials was assessed using the criteria of the Cochrane Incontinence Group and other criteria. There was 100% concordance between the reviewers in this respect.

Overall, there was wide variation in the quality of the trials. Only seven (Benoist 1999; Dunn 2003; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Irani 1995; Kelleher 2002; Webster 2006) of the twenty‐six trials described all the aspects of methodological quality defined by the Incontinence Group assessment criteria. A median of five criteria were described in the trials. Details regarding statistical power, minimum clinical differences sought and sample size calculations were reported in four trials (Benoist 1999; Dunn 2003; Hakvoort 2004; Webster 2006). The alpha level used in their statistical tests was also reported .

Use of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria

A broad description of the inclusion and/or exclusion criteria was provided in 19 trials (Benoist 1999; Crowe 1994; Dunn 2003; Ganta 2005; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Ind 1993; Irani 1995; Kelleher 2002; Lau 2004; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Oberst 1981; Sun 2004; Taube 1989; Toscano 2001; Webster 2006; Williamson 1982; Wilson 2000), however the quality of reporting of inclusion and exclusion criteria was extremely variable. Description of precise inclusion and exclusion criteria was reported in nine trials (Benoist 1999; Crowe 1994; Dunn 2003; Ind 1993; Irani 1995; Oberst 1981; Webster 2006; Williamson 1982; Wilson 2000). A clear description of the exclusion criteria only was reported in three trials (Hakvoort 2004; Kelleher 2002; Taube 1989).

Allocation sequence generation

The method of sequence generation in seven trials was by using random numbers (Benoist 1999; Chillington 1992; Dunn 2003; Kelleher 2002; McDonald 1999; Schiotz 1996; Webster 2006), one trial used permuted tables (Irani 1995), another alternation (Noble 1990), hospital numbers (Lau 2004) and this was not reported in the remaining 16 trials.

Allocation concealment

Adequate allocation concealment (A) was reported in seven trials (Benoist 1999; Chillington 1992; Dunn 2003; Hakvoort 2004; Schiotz 1996; Webster 2006; Wilson 2000). The process of allocation concealment was unclear (B) in 17 trials and allocation concealment (C) was inadequately reported in two trials (Lau 2004; Noble 1990).

Intention‐to‐treat analysis

An intention to treat (ITT) analysis should ideally include data from all those who were randomised. Inclusion of those participants who withdraw or drop out from a trial is important as losing their data could result in bias. Analysis on an intention to treat basis was reported in only six trials (Benoist 1999; Dunn 2003; Ganta 2005; Lau 2004; Webster 2006; Wilson 2000). However, no trials reported that participants were moved between groups for analysis.

Withdrawals and dropouts

Fourteen trials provided a clear description of the withdrawals and dropouts. Eleven trials (Dunn 2003; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Kelleher 2002; Lau 2004; Nielson 1985; Taube 1989; Toscano 2001; Williamson 1982; Wilson 2000; Wyman 1987) reported that there were no dropouts and one trial (Ganta 2005; McDonald 1999) stated only the total number of participants who dropped out.

Blinded outcome assessment

Due to the nature of interventions, blinding of the participant, care provider and assessor was not possible.

Methods to assess outcomes

The method used to diagnose urinary retention was reported in only three trials (Crowe 1994, Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Irani 1995; Sun 2004). Crowe (Crowe 1994) measured the post‐void residual volume by reinserting an indwelling urethral catheter ten hours following its initial removal. A post‐void residual volume of greater than 150 ml was accepted as urinary retention necessitating recatheterisation. Two trials defined urinary retention as post‐void residual volume of more than 100 ml, for two consecutive micturitions (Guzman 1994; Sun 2004). Irani used uroflowmetry (Irani 1995), Hakvoort (Hakvoort 2004) used ultrasound scanner and Lau palpated the bladder (Lau 2004) to investigate urinary retention.

Effects of interventions

1. Removal of catheter at one time of day versus another time, eg late night (2200 to 2400 hours) versus early morning (0600 to 0800 hours)

Eleven trials (three of them new: Ganta 2005; Webster 2006; Wilson 2000) compared catheter removal at different times of the day. However, meta‐analysis was restricted due to the limited information available and clinical heterogeneity between the trials.

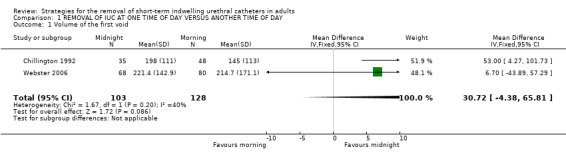

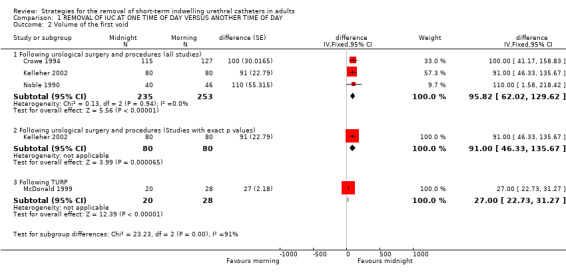

Volume of the first void (Comparisons 01.01, 01.02, Other Data Tables 01.03)

Nine trials (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ganta 2005; Ind 1993; Kelleher 2002; Lyth 1997; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Webster 2006) reported data on the volume of the first void following the removal of the indwelling urethral catheter. The volume of the first void varied widely (eg in Ind 1993: 5 to 600 ml) (Ind 1993) and this was reflected in large standard errors and standard deviations. Seven trials (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ind 1993; Kelleher 2002; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Webster 2006), reported that participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed at midnight passed larger volumes at their first void, irrespective of reason for initial catheterisation. Pooled results (Crowe 1994; Kelleher 2002; Noble 1990) demonstrated that following urological surgery and procedures, participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed at midnight passed significantly larger volumes at their first void (Difference (fixed) 95.82; 95% CI 62.02 to 129.62; Comparison 01.02.01). Similar findings were reported for participants following TURP (McDonald 1999) (Difference (fixed) 27; 95% CI 22.73 to 31.27; Comparison 01.02.03). One trial (Ganta 2005) reported no statistically significant difference and in the other trial (Lyth 1997) it was unclear if the difference was statistically significant. The mean differences in the trials ranged from 27ml to 110ml.

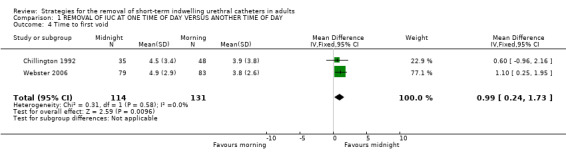

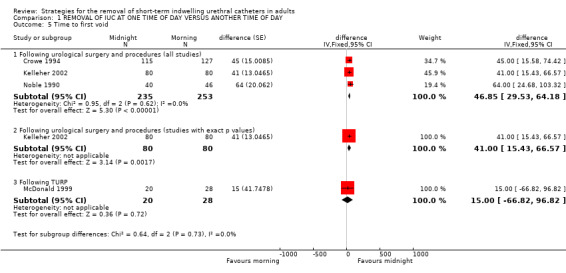

Time to first void (Comparison 01.04, 01.05, 01.06)

Time to first void was reported in eight trials (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ganta 2005; Ind 1993; Kelleher 2002; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Webster 2006). This varied widely between individual participants (eg 10 minutes to 13 hours 15 minutes).

In seven trials, (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ganta 2005; Kelleher 2002; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Webster 2006) the time to first void was longer in the groups allocated midnight removal, which was significantly so in four trials. The exception was a trial (Ind 1993) following gynaecological surgery when the time was significantly shorter after removal at midnight (Other Data Table 01.06.01).

Length of hospitalisation (Comparison 01.07, 01.08, 01.09)

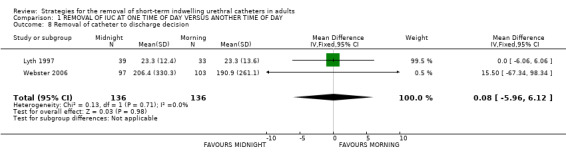

Length of hospitalisation was reported in 10 trials (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ganta 2005; Ind 1993; Kelleher 2002; Lyth 1997; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Webster 2006; Wilson 2000). In eight trials, the length of hospitalisation was shorter after midnight catheter removal. In the six trials providing adequate data, the chances of not being discharged on the day of catheter removal were lower by about a third (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.64 to 0.79; Comparison 01.07) (Crowe 1994; Ganta 2005; Kelleher 2002; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Wilson 2000), although with significant statistical heterogeneity between the trials. Two trials (Lyth 1997; Webster 2006) showed no difference in time to discharge decision (WMD 0.08; 95% CI ‐5.96 to 6.12; Comparison 01.08). In the trial by Ind (Ind 1993), the median hospital stay was two days shorter in the group allocated midnight removal; secondary analysis suggested that this difference may be greater when catheterisation followed gynaecological surgery involving the bladder or urethra (Other Data Table 01.09). The last trial (Chillington 1992) also showed shorter hospital stay after midnight removal, but no estimates of dispersion (eg SD) were reported (Other Data Table 01.09.03) (Chillington 1992).

Cost‐effectiveness

Only one trial addressed cost‐effectiveness. The authors (Chillington 1992) reported that the reduced length of stay for participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed at midnight resulted in an annual saving of seventeen bed‐days a year, which was equivalent to an annual saving for the unit of UK £1500.

Need for recatheterisation for urinary retention (Comparison 01.10)

Eight trials (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ganta 2005; Ind 1993; Kelleher 2002; Lyth 1997; Webster 2006; Wyman 1987) reported on the number of participants who developed urinary retention following catheter removal and required recatheterisation. Overall, 57/857 (7%) allocated midnight removal compared with 76/833 (9%) allocated morning removal were recatheterised (RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.58 to 1.08; Comparison 01.10).

Time of day recatheterised

Two trials (Chillington 1992; Wyman 1987) investigated the time of day participants were recatheterised for urinary retention. The time between initial removal and recatheterisation ranged from seven (Wyman 1987) to 80 hours (Chillington 1992). Chillington (Chillington 1992) however, did report that participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed at night were more likely to be recatheterised during working hours (but statistical significance was not stated).

Indwelling urethral catheter not removed on time (Comparison 01.11)

Three trials (Chillington 1992; Kelleher 2002; Noble 1990) investigated if the indwelling urethral catheters were removed on time. There was significant heterogeneity between the trials. In two trials, significantly fewer of the midnight catheter removals were not on time, whereas in a third trial (Chillington 1992) the pattern was reversed.

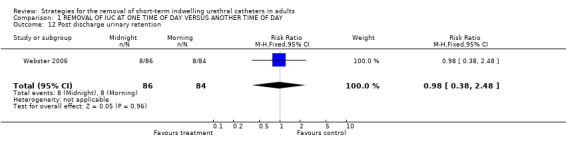

Post discharge urinary retention (Comparison 01.12)

One trial (Webster 2006) reported on development of urinary retention following discharge and indicated that eight participants in each group (10%) developed this complication (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.38 to 2.48; Comparison 01.12).

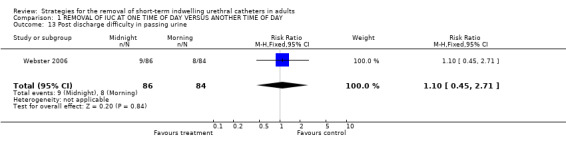

Post discharge difficulty in passing urine (Comparison 01.13)

In the only trial (Webster 2006) that assessed this outcome there was no significant difference between the two groups (9/86 versus 8/84, RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.45 to 2.71; Comparison 01.13).

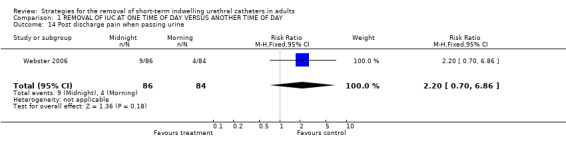

Post discharge pain when passing urine (Comparison 01.14)

One trial that assessed this outcome reported that although fewer participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed in the morning developed pain following discharge, this did not reach statistical significance (9/86 versus 4/84, RR 2.20; 95% CI 0.70 to 6.86; Comparison 01.14) (Webster 2006).

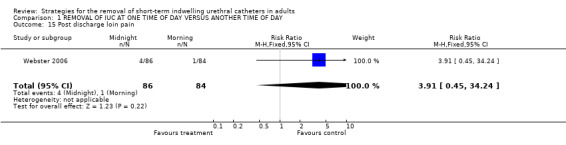

Post discharge loin pain (Comparison 01.15)

In the same trial (Webster 2006), 4/86 compared with 1/84 participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed in the morning experienced loin pain following discharge (RR 3.91; 95% CI 0.45 to 34.24; Comparison 01.15) (Webster 2006).

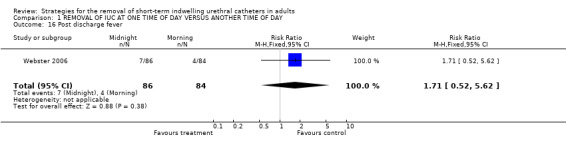

Post discharge fever (Comparison 01.16)

No significant difference in the number of participants who developed fever between the two groups was reported (7/86 versus 4/84, RR 1.71; 95% CI 0.52 to 5.62; Comparison 01.16) (Webster 2006).

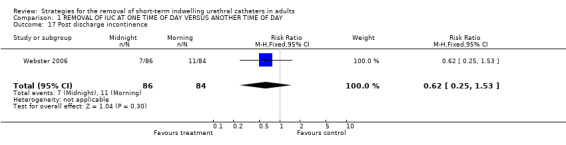

Post discharge incontinence (Comparison 01.17)

Seven out of 86 participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed at night, compared with 4 of 84 in the morning group developed urinary incontinence after discharge (RR 0.62; 95% CI 0.25 to 1.53; Comparison 01.17) (Webster 2006).

Patient satisfaction

One new trial in this review update (Ganta 2005) reported measures of participant satisfaction and indicated that removal of the indwelling urethral catheter at midnight was associated with more sleep disturbances (P=0.004). In another trial, Lyth 1997 indicated that participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed at midnight had disturbed sleep, were tired and confused in the morning and had a delayed establishment of voiding pattern. However, five other trials (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ind 1993; Kelleher 2002; Noble 1990) reported that midnight removal of indwelling urethral catheters did not interrupt the participants' sleep: some participants went back to sleep immediately after the indwelling urethral catheter was removed, and the others slept through the removal process.

When recatheterisation was required, Chillington (Chillington 1992) reported that two of the three participants who had their indwelling urethral catheters removed in the morning, were recatheterised at "unsocial hours" (20.30 and 03.00 hours). This was reported to be not only distressing for the participant but also resulted in recatheterisation being performed by a doctor who was on call and not familiar with the case.

2. Shorter duration versus longer duration of catheter use

Thirteen trials (five of them new in this update: Dunn 2003; Hakvoort 2004; Lau 2004; Sun 2004; Toscano 2001) included in this review investigated the effects of duration of catheterisation on outcomes following:

treatment for urethral strictures (Hansen 1984; Nielson 1985);

acute retention of urine (Lau 2004; Taube 1989);

surgery for urinary stress (Guzman 1994; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004);

transurethral surgery (Irani 1995; Koh 1994; Toscano 2001);

rectal surgery (Benoist 1999);l

hysterectomy (Dunn 2003);

vaginal prolapse surgery (Hakvoort 2004).

The duration of catheterisation ranged from 1 to 28 days.

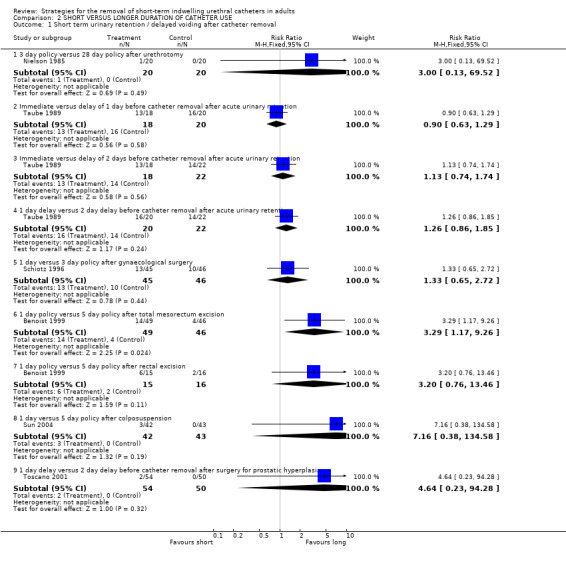

Short‐term urinary retention/delayed voiding after indwelling urethral catheter removal (Comparison 02.01)

Six trials (Benoist 1999; Nielson 1985; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004; Taube 1989; Toscano 2001) reported on the incidence of short‐term urinary retention/delayed voiding following removal of the indwelling urethral catheter (Comparison 02.01). The clinical indications varied, the numbers allocated to the various policies compared were small, and the confidence intervals were all wide. There was a tendency for fewer participants to have these problems when removal was delayed for some days.

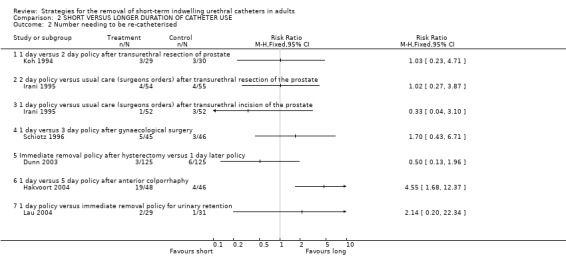

Number of patients who required recatheterisation (Comparison 02.02)

This outcome was reported in six trials (Dunn 2003; Hakvoort 2004; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; Lau 2004; Schiotz 1996). Again, the confidence intervals were all wide, reflecting the small number of events in the comparisons, and except for one small trial (Hakvoort 2004) none of the differences observed were statistically significant.

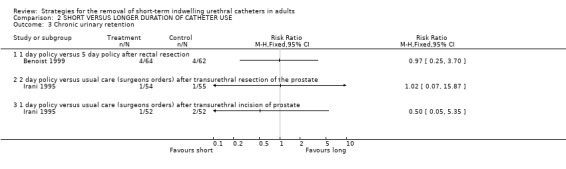

Chronic urinary retention (Comparison 02.03)

Two trials (Benoist 1999, Irani 1995) reported the frequency of chronic urinary retention. Between them they included only 13 cases of chronic retention with similar numbers originally managed with early or delayed catheter removal (Comparison 02.03).

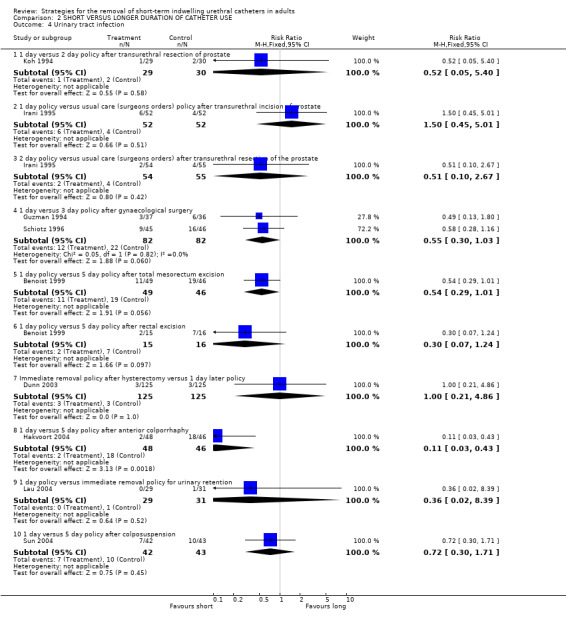

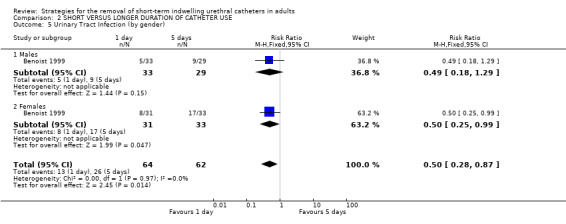

Urinary tract infection (Comparisons 02.04; 02.05)

Nine trials reported urinary tract infections (Benoist 1999; Dunn 2003; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; Lau 2004; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004). The data were consistent with an increasing risk of infection with later removal, irrespective of gender, although the difference was statistically significant in only one trial (Comparison 02.04.08) (Hakvoort 2004).

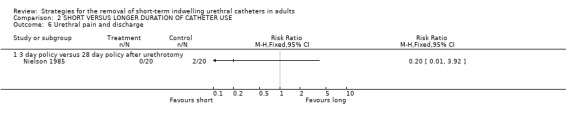

Urethral pain and discharge (Comparison 02.06)

One trial (Nielson 1985) investigated the effect of removal of the indwelling urethral catheter after either three or 28 days following urethrotomy. No participants reported urethral pain and discharge in the 20 in the early removal group compared with two amongst the 20 in the late group (Comparison 02.06.01).

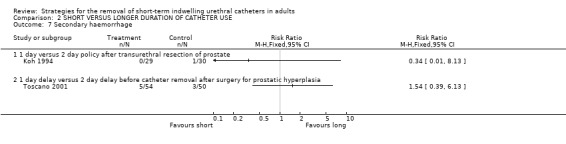

Secondary haemorrhage (Comparison 02.07)

Only nine cases were reported in the two trials with data. Koh (Koh 1994) reported a single case of secondary haemorrhage in 30 participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed after two days following TURP compared with none amongst 29 whose catheters were removed after one day (Comparison 02.07.01). There were 5 after 1‐day compared with 3 cases after 2‐day delay after prostate surgery for hyperplasia in another trial (Comparison 02.07.02) (Toscano 2001).

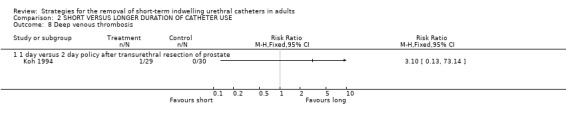

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (Comparison 02.08)

There was a single case of DVT in the early removal group in Koh's trial (Comparison 02.08.01) (Koh 1994).

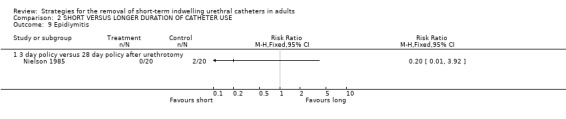

Epididymitis (Comparison 02.09)

Two of 20 participants whose catheters were removed 28 days after urethrotomy developed epididymitis compared with none of 20 in the three‐day removal group (Comparison 02.09.01) (Nielson 1985).

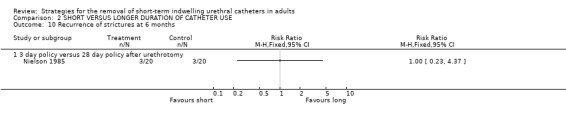

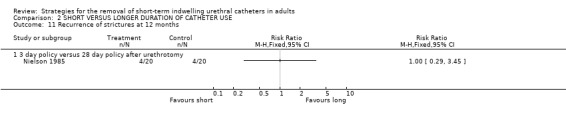

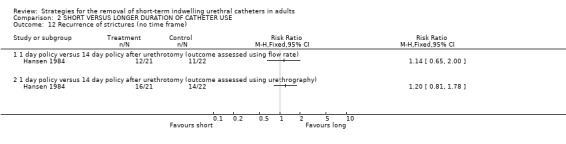

Recurrence of strictures (Comparisons 02.10; 02.11; 02.12)

No statistically significant difference in the recurrence of strictures at either six (3/20 versus 3/20) or 12 months (4/20 versus 4/20) was identified in participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed after either three days or 28 days following urethrotomy (Comparisons 02.10.01; 02.11.01) (Nielson 1985). Hansen (Hansen 1984) investigated the recurrence of strictures using the flow rate and by urethrography. Both methods demonstrated no statistically significant difference in this outcome if the indwelling urethral catheter was removed after one or fourteen days following urethrotomy (02.12.01; 02.12.02).

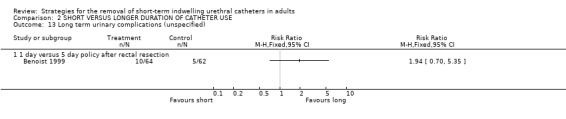

Long‐term urinary complications (Comparison 02.13)

One study (Benoist 1999) that investigated the incidence of (unspecified) long‐term urinary complications reported no statistically significant difference in this outcome in participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed after one or five days following proctectomy (10/64 versus 5/62) (Comparison 02.13.01).

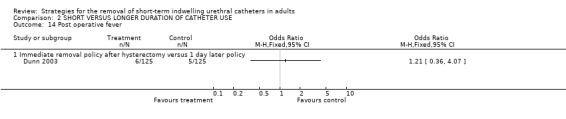

Post operative fever (Comparison 02.14)

Five of 125 participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed one day after hysterectomy developed fever compared to six of 125 participants whose indwelling urethral catheters were removed immediately following surgery (Comparison 02.14.01) (Dunn 2003).

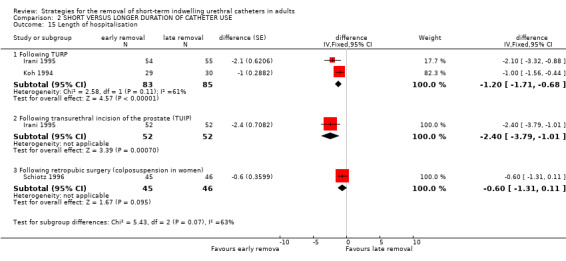

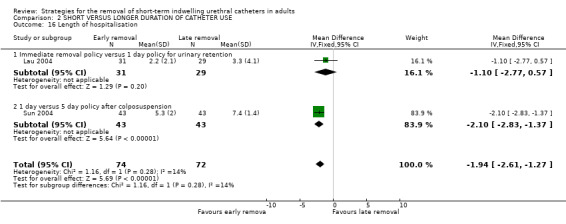

Length of hospitalisation (Comparison 02.15, 02.16, Other Data Tables 02.17)

Six trials (Hakvoort 2004; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; Lau 2004; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004) reported data on the length of hospitalisation. All of the trials reported a reduction in the length of hospitalisation with early removal (although not all were statistically significant) following:

transurethral surgery (e.g. mean reduction of 1.2 days, 95% CI ‐1.71 to ‐0.68, Comparisons 02.15.01; 02.15.02) (Koh 1994; Irani 1995);

colposuspension surgery (Comparison 02.15.03, not statistically significant) (Schiotz 1996) and (Comparison 02.16.02) (Sun 2004);

anterior colporraphy (Other Data Tables 02.17.01) (Hakvoort 2004); and

urinary retention (Comparison 02.16.01, not statistically significant) (Lau 2004).

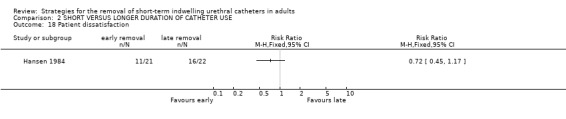

Patient satisfaction (Comparison 02.18)

In a single trial comparing one day with 14 days of catheterisation, fewer participants who had been catheterised for one day were dissatisfied with their treatment although the results were not statistically significant (RR 0.72; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.17; Comparison 02.18) (Hansen 1984).

3. Flexible duration versus fixed duration of catheter use

No trials were found which addressed this comparison.

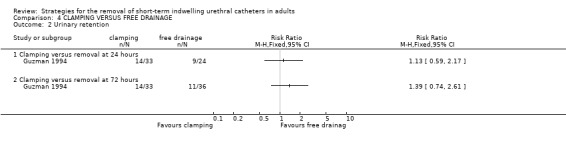

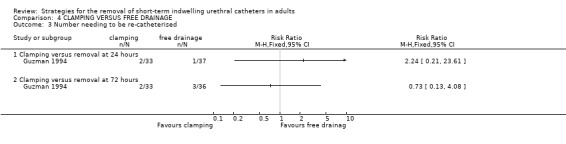

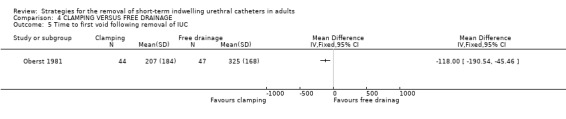

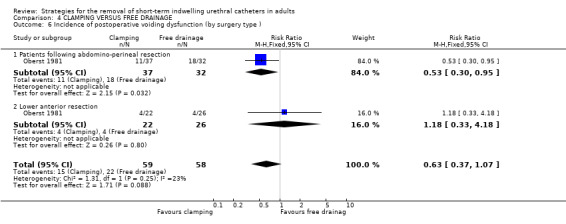

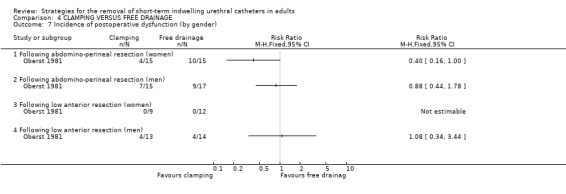

4. Clamping versus free drainage before catheter removal

Three trials (Guzman 1994; Oberst 1981; Williamson 1982) involving a total of 234 participants compared clamping the indwelling urethral catheter prior to removal with free drainage. All three trials used different clamping regimens; therefore the results could not be combined in a meta‐analysis.

The available data have been tabulated for urinary tract infection (Comparison 04.01); urinary retention (Comparison 04.02); recatheterisation (Comparison 04.03), time to first void (Comparisons 04.04; 04.05); and postoperative voiding dysfunction (Comparison 04.06). The data in all comparisons were few and hence the confidence intervals were all wide. In the two trials with data (Oberst 1981; Williamson 1982), the time to first void was shorter after prior catheter clamping.

5. Removal using prophylactic alpha blocker drugs versus other methods

No trials were found which addressed this comparison.

Discussion

This systematic review was undertaken to investigate policies for the removal of urethral catheters used for the short‐term management of adults and children. An exhaustive search of the literature resulted in 26 published trials (eight new) that were eligible for inclusion in this review. The trials involved both male and female adult patients. None involved children; therefore the findings of the review cannot be generalised to this population. While all the 26 trials met the methodological criteria for inclusion in the review, no study was described as either being single or double‐blind as this was not possible given the nature of the intervention.

The interpretation of the review is complicated by differences between the trials in terms of reasons for catheterisation, the types of surgery, the types of anaesthesia used during the surgical procedure and the hydration status of the patients. The type of anaesthesia used was reported in only four trials (Ind 1993; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; Lau 2004) and only one trial (Webster 2006) reported on the hydration status of the patients although two trials (Lyth 1997; Wilson 2000) reported that patients were asked to drink copiously. The absence of such relevant information should be considered when interpreting the findings. The lack of measures of dispersion (eg standard deviations) also prevented the use of many of the data in the meta‐analyses.

While only trials that involved similar participants were combined statistically for a particular outcome, the data from all trials addressing the same broad question for that outcome were tabulated in the same comparison tables. Readers may question whether it is appropriate to consider such trials together, but the approach did allow patterns to be identified. We recognise that these should be interpreted cautiously given the heterogeneity in terms of the reasons for catheterisation, and the potential for the results of small trials like those reported here to over or underestimate treatment differences.

A discussion relating to each comparison is presented below.

Removal of catheter at one time of day versus another time (eg late night versus early morning)

Eleven trials involving 1389 participants compared late night with early morning removal of indwelling urethral catheters. The reasons for catheterisation were variable, but the most common was TURP and other urological surgery. The trials were generally consistent in showing after removal at midnight (rather than early morning):

larger volumes of the first void;

longer times to first void (although one trial suggests the opposite);

shorter length of hospitalisation (with one trial suggesting the opposite);

no clear statistical difference in the need for recatheterisation, but with confidence intervals that do not rule out an important difference;

limited evidence suggesting that the midnight removal avoided recatheterisation at unsocial hours;

no clear difference in the likelihood of a catheter being removed on time;

and a suggestion that it is cost‐effective.

Urinary retention is a common occurrence following the removal of the indwelling urethral catheter (Crowe 1994). Therefore monitoring the volume of the first void as an indicator of voiding dysfunction is imperative (Crowe 1994). Larger volumes of urine demonstrates a return to normal voiding function.

Duration of catheterisation

Thirteen trials involving 1422 participants compared various durations of catheterisation. The wide range (from 1 to 28 days), heterogeneity of patient groups and small sample sizes complicated and limit conclusions. As might be expected, there was a tendency for later removal to be associated with fewer short‐term voiding problems, but increasing risk of urinary tract infection, more dissatisfaction and longer hospital stay.

Clamping of the indwelling urethral catheter

Three trials involving 234 participants compared clamping versus free drainage of the indwelling urethral catheter prior to removal. Unlike the other two comparisons, the trials mainly comprised women. Two of the three trials clearly described the protocol for clamping prior to the removal of the indwelling urethral catheters. The limited evidence obtained from the review does not provide a robust base for the development of practice guidelines.

Resource implications

In clinical practice, the timing of removal and the duration of the indwelling urethral catheter have significant resource implications. The principal determinant of cost is the length of hospital stay. The analyses of this outcome for timing of removal are difficult to interpret: while most trials were consistent with shorter hospital stay, the size of the difference varied significantly. A similar pattern of results was obtained for duration of catheterisation. These data do provide a credible range for the potential effect of midnight removal and shorter duration of catheterisation on length of hospital stay but do not provide a reliable summary estimate.

In this review only one trial amongst 100 participants (Chillington 1992) undertook a simple cost analysis that suggested that midnight removal of the indwelling urethral catheter was associated with an annual saving of UK £1500, as more participants were discharged on the same day following the removal of the indwelling urethral catheter. However it should be noted that the estimate is based on costs in the early 1990s of 17 extra bed days. Nevertheless this finding may have significant implications for hospital administrators relating to economic benefits associated with shorter length of stay and efficient discharge planning. It can be inferred from these trials that early (within 1 to 3 days) removal of the indwelling urethral catheter would decrease hospital costs. However as none of the other trials reported costs it is not possible to undertake a comparison between the studies. More detailed assessment of the economic impact of the timing and the duration of the indwelling urethral catheter in future research would be beneficial.

Patient satisfaction is assuming greater significance as a measure of quality of health care. Two trials reported formal methods to assess participant satisfaction: one reported a significant association between sleep disturbances and removal of the indwelling urethral catheter at midnight (Ganta 2005); and the other showed more participants dissatisfied with longer duration of catheterisation (though not significantly so, Hansen 1984). Others that used informal reports from participants indicated that removal of the indwelling urethral catheter at midnight did not cause any inconvenience or distress. Participants reported they were pleased that the indwelling urethral catheter was removed at midnight enabling them to have a restful night.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence is consistent with midnight, rather than early morning, catheter removal leading to shorter hospital stays with consequent resource savings. Other evidence suggests that the timing of catheter removal is a balance between avoiding increased risk of infection (by early removal) and circumventing voiding dysfunction (by later removal). Early removal appears to reduce mean hospital stay, however. The evidence for assessing clamping indwelling urethral catheters prior to removal is limited, and there was no evidence regarding the use of alpha adrenergic blocker drugs. Until stronger evidence becomes available practices relating to clamping indwelling urethral catheters will continue to be dictated by local preferences and cost factors.

Implications for research.

This review has provided a guide to future priorities for research. 1. Further randomised trials using larger sample sizes are needed to address all the questions in the review more precisely and reliably, and to allow secondary analyses amongst discrete subgroups. 2. Further trials should include the range of outcomes sought in this review, including measures of quality of life and resource use. 3. Outcome measures (eg urinary retention) need to be well defined and also confirm to standardised definitions (where these exist e.g. for catheter‐associated infection) to facilitate comparisons between studies as well as to increase the robustness of further trials. The main issues are the need for recatheterisation and time to hospital discharge. 4. Evaluation in wider settings and on specific groups of patients would enhance generalisability. 5. Future randomised trials should compare the effects of midnight or early morning indwelling urethral catheter removal to removal at any time of the day. 6. Similarly, randomised trials using larger samples are needed to provide robust evidence of the effects of clamping or free drainage of the indwelling urethral catheters, and adjunctive use of alpha blockers, prior to removal. 7. Examination of supra‐pubic catheters should be included in further research.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2003 Review first published: Issue 1, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 February 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. Update Issue 2, 2007. Twenty‐six trials (eight new) involving a total of 2933 participants were included in this first update of the review. One trial (Guzman 1994) included three treatment groups. Eleven (three new) compared late night versus early morning removal of catheters (Chillington 1992; Crowe 1994; Ganta 2005; Ind 1993; Kelleher 2002; Lyth 1997; McDonald 1999; Noble 1990; Webster 2006; Wilson 2000; Wyman 1987); thirteen (five new) compared various durations of catheterisation (Benoist 1999; Dunn 2003; Guzman 1994; Hakvoort 2004; Hansen 1984; Irani 1995; Koh 1994; Lau 2004; Nielson 1985; Schiotz 1996; Sun 2004; Taube 1989; Toscano 2001); and three (Guzman 1994; Oberst 1981; Williamson 1982) compared clamping to free drainage. |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the General Managers of the South Western Sydney Area Health Service (Australia) for funding this review. In addition we would like to acknowledge the assistance of the librarians and library staff of the Liverpool Health Service library for their assistance with the development of the search strategy and the timely retrieval of articles and finally to Ms Rosemary Chester for her support throughout the project. We would also like to thank Ms Crowe, Ms McDonald and Dr Chen for responding to our queries about providing additional data.

The review authors would like to thank The Cochrane Incontinence Group referees and Editors for their comments to improve the review. Special thanks are due to Peter Herbison for statistical advice.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Details of the search methods and terms used for the extra specific searches for this review

Electronic bibliographic databases The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched.

CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library 2006, Issue 2), (on web, Update Software site, via OVID in July 2006) using the following search strategy:

1. Urin* 2. Ureth* 3. (1 or 2) 4. Cath* 5. (3 and 4) 6. Time 7. Morn* 8. Night 9. Dawn 10. Dusk 11. Evening 12. Afternoon 13. Noon 14. Day 15. 6AM 16. (6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15) 17. (5 and 16) 18. Suprapubic 19. (17 not 18) 20. Removal 21. (19 and 20) Key: * = truncation symbol.

MEDLINE (via OVID) (years searched: January 1966 to 12 July 2006) using the following search terms:

1. urinary catheterization/ or catheter, urinary/ 2. (catheter$ and (urin$ or urethra$)).mp. 3. 1 or 2 4. (remov$ or withdraw$).mp. 5. Time Factors/ 6. (time or timing or morning$ or afternoon$ or evening$ or night$ or day$).mp. 7. 5 or 6 8. 3 and 4 and 7 Key: / = MeSH term with all subheadings; $ = truncation symbol; mp = map, searches a number of fields including MeSH terms and textwords in titles and abstracts

EMBASE (years searched: January 1980 to 12 July 2006) using the following search terms:

1. urinary catheterization/ or catheter, urinary/ 2. (catheter$ and (urin$ or urethra$)).mp. 3. 1 or 2 4. (remov$ or withdraw$).mp. 5. Time Factors/ 6. (time or timing or morning$ or afternoon$ or evening$ or night$ or day$).mp. 7. 5 or 6 8. 3 and 4 and 7 Key: / = MeSH term with all subheadings; $ = truncation symbol; mp = map, searches a number of fields including EMTREE terms and textwords in titles and abstracts

CINAHL (years searched: January 1982 to 12 July 2006) using the following search terms:

1. urinary catheterization/ or catheter, urinary/ 2. (catheter$ and (urin$ or urethra$)).mp. 3. 1 or 2 4. (remov$ or withdraw$).mp. 5. Time Factors/ 6. (time or timing or morning$ or afternoon$ or evening$ or night$ or day$).mp. 7. 5 or 6 8. 3 and 4 and 7 Key: / = MeSH term with all subheadings; $ = truncation symbol; mp = map, searches a number of fields including CINAHL subject terms and textwords in titles and abstracts

Nursing Collection Journals @ OVID (years searched: January 1995 to January 2002) using the following search terms:

1. urinary catheterization/ or catheter, urinary/ 2. (catheter$ and (urin$ or urethra$)).mp. 3. 1 or 2 4. (remov$ or withdraw$).mp. 5. Time Factors/ 6. (time or timing or morning$ or afternoon$ or evening$ or night$ or day$).mp. 7. 5 or 6 8. 3 and 4 and 7 Key: / = MeSH term with all subheadings; $ = truncation symbol; mp = map, searches a number of fields including textwords in titles and abstracts

Conference Proceedings The following conference proceedings were scanned briefly:

International Continence Society (ICS), Annual Meeting (1995 to 2000 inclusive);

International Urogynecological Association (IUGA), Annual Meeting (2000 and 2001);

Hong Kong Urological Association, Annual Meeting (1995 to 2001 inclusive).

Other Sources The reference lists of relevant articles were searched for other possible relevant trials. Manufacturers, researchers and experts in the field were contacted to ask for other possibly relevant trials, published or unpublished.

We did not impose any language or other limits on any of the searches.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Volume of the first void | 2 | 231 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 30.72 [‐4.38, 65.81] |

| 2 Volume of the first void | 4 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Following urological surgery and procedures (all studies) | 3 | 488 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 95.82 [62.02, 129.62] |

| 2.2 Following urological surgery and procedures (Studies with exact p values) | 1 | 160 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 91.0 [46.33, 135.67] |

| 2.3 Following TURP | 1 | 48 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 27.0 [22.73, 31.27] |

| 3 Volume of first void | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.1 Following gynaecological surgery | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.2 Following bladder neck incision | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.3 Following TURP | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4 Time to first void | 2 | 245 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.24, 1.73] |

| 5 Time to first void | 4 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Following urological surgery and procedures (all studies) | 3 | 488 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 46.85 [29.53, 64.18] |

| 5.2 Following urological surgery and procedures (studies with exact p values) | 1 | 160 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 41.0 [15.43, 66.57] |

| 5.3 Following TURP | 1 | 48 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | 15.0 [‐66.82, 96.82] |

| 6 Time to first void (no SDs) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6.1 Following gynaecological surgery | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 6.2 Following TURP | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 7 Length of hospitalization | 6 | 692 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.64, 0.79] |

| 7.1 Number of patients not discharged on day of IUC removal (urological procedures and surgery) | 4 | 572 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.62, 0.78] |

| 7.2 Number of patients not discharged on day of IUC removal (TURP) | 2 | 120 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.63, 1.01] |

| 8 Removal of catheter to discharge decision | 2 | 272 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.08 [‐5.96, 6.12] |

| 9 Length of hospitalization | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 9.1 Gynaecological surgery involving the bladder /urethra | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 9.2 Gynaecological surgery not involving the bladder/urethra | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 9.3 Following TURP | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 10 Incidence of recatheterization | 8 | 1690 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.58, 1.08] |

| 10.1 TURP | 2 | 186 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.36, 2.35] |

| 10.2 Urological surgery and procedures | 4 | 1214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.60, 1.33] |

| 10.3 Gynaecological surgery | 1 | 95 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.18, 1.04] |

| 10.4 General medical and surgical patients | 1 | 195 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.38, 1.66] |

| 11 IUC not removed on time | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 12 Post discharge urinary retention | 1 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.38, 2.48] |

| 13 Post discharge difficulty in passing urine | 1 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.45, 2.71] |

| 14 Post discharge pain when passing urine | 1 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.20 [0.70, 6.86] |

| 15 Post discharge loin pain | 1 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.91 [0.45, 34.24] |

| 16 Post discharge fever | 1 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [0.52, 5.62] |

| 17 Post discharge incontinence | 1 | 170 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.25, 1.53] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 1 Volume of the first void.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 2 Volume of the first void.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 3 Volume of first void.

| Volume of first void | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Midnight removal | Morning removal | Significance |

| Following gynaecological surgery | |||

| Ind 1993 | 275 ml (range 10 to 600 ml) | 100 ml (range 5 to 450 ml) | P<0.0001 |

| Following bladder neck incision | |||

| Lyth 1997 | 385 ml | 343 ml | not given |

| Following TURP | |||

| Ganta 2005 | Mean Volume 131 mls | Mean Volume 152 mls | Not significant |

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 4 Time to first void.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 5 Time to first void.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 6 Time to first void (no SDs).

| Time to first void (no SDs) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Midnight removal | Morning removal | Significance | Difference | Weight |

| Following gynaecological surgery | |||||

| Ind 1993 | Median time 3 hours 20 mins | Median time 5 hours | P =0.012 | ||

| Following TURP | |||||

| Ganta 2005 | Mean Time 134 minutes | Mean Time 122 minutes | Not significant | ||

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 7 Length of hospitalization.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 8 Removal of catheter to discharge decision.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 9 Length of hospitalization.

| Length of hospitalization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Midnight removal | Morning removal | significance | difference | weight |

| Gynaecological surgery involving the bladder /urethra | |||||

| Ind 1993 | 9 days (range 4‐17 days) | 12 days (range 5‐20 days) | p=0.043 | ||

| Gynaecological surgery not involving the bladder/urethra | |||||

| Ind 1993 | 6 days (range 1‐14 days) | 7 days (range 2‐18 days) | |||

| Following TURP | |||||

| Chillington 1992 | 4.7 days | 5.4 days | |||

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 10 Incidence of recatheterization.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 11 IUC not removed on time.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 12 Post discharge urinary retention.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 13 Post discharge difficulty in passing urine.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 14 Post discharge pain when passing urine.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 15 Post discharge loin pain.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 16 Post discharge fever.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 REMOVAL OF IUC AT ONE TIME OF DAY VERSUS ANOTHER TIME OF DAY, Outcome 17 Post discharge incontinence.

Comparison 2. SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Short term urinary retention / delayed voiding after catheter removal | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 3 day policy versus 28 day policy after urethrotomy | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 69.52] |

| 1.2 Immediate versus delay of 1 day before catheter removal after acute urinary retention | 1 | 38 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.63, 1.29] |

| 1.3 Immediate versus delay of 2 days before catheter removal after acute urinary retention | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.74, 1.74] |

| 1.4 1 day delay versus 2 day delay before catheter removal after acute urinary retention | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.86, 1.85] |

| 1.5 1 day versus 3 day policy after gynaecological surgery | 1 | 91 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.65, 2.72] |

| 1.6 1 day policy versus 5 day policy after total mesorectum excision | 1 | 95 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.29 [1.17, 9.26] |

| 1.7 1 day policy versus 5 day policy after rectal excision | 1 | 31 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.2 [0.76, 13.46] |

| 1.8 1 day versus 5 day policy after colposuspension | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.16 [0.38, 134.58] |

| 1.9 1 day delay versus 2 day delay before catheter removal after surgery for prostatic hyperplasia | 1 | 104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.64 [0.23, 94.28] |

| 2 Number needing to be re‐catheterised | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 1 day versus 2 day policy after transurethral resection of prostate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 2 day policy versus usual care (surgeons orders) after transurethral resection of the prostate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 1 day policy versus usual care (surgeons orders) after transurethral incision of the prostate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.4 1 day versus 3 day policy after gynaecological surgery | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.5 Immediate removal policy after hysterectomy versus 1 day later policy | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.6 1 day versus 5 day policy after anterior colporrhaphy | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.7 1 day policy versus immediate removal policy for urinary retention | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Chronic urinary retention | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 1 day policy versus 5 day policy after rectal resection | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 2 day policy versus usual care (surgeons orders) after transurethral resection of the prostate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 1 day policy versus usual care (surgeons orders) after transurethral incision of prostate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Urinary tract infection | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 1 day versus 2 day policy after transurethral resection of prostate | 1 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.05, 5.40] |

| 4.2 1 day policy versus usual care (surgeons orders) policy after transurethral incision of prostate | 1 | 104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.45, 5.01] |

| 4.3 2 day policy versus usual care (surgeons orders) after transurethral resection of the prostate | 1 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.10, 2.67] |

| 4.4 1 day versus 3 day policy after gynaecological surgery | 2 | 164 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.30, 1.03] |

| 4.5 1 day policy versus 5 day policy after total mesorectum excision | 1 | 95 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.29, 1.01] |

| 4.6 1 day policy versus 5 day policy after rectal excision | 1 | 31 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.07, 1.24] |

| 4.7 Immediate removal policy after hysterectomy versus 1 day later policy | 1 | 250 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.21, 4.86] |

| 4.8 1 day versus 5 day policy after anterior colporrhaphy | 1 | 94 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.03, 0.43] |

| 4.9 1 day policy versus immediate removal policy for urinary retention | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.02, 8.39] |

| 4.10 1 day versus 5 day policy after colposuspension | 1 | 85 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.30, 1.71] |

| 5 Urinary Tract Infection (by gender) | 1 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.28, 0.87] |

| 5.1 Males | 1 | 62 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.18, 1.29] |

| 5.2 Females | 1 | 64 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.25, 0.99] |

| 6 Urethral pain and discharge | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 3 day policy versus 28 day policy after urethrotomy | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7 Secondary haemorrhage | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7.1 1 day versus 2 day policy after transurethral resection of prostate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.2 1 day delay versus 2 day delay before catheter removal after surgery for prostatic hyperplasia | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8 Deep venous thrombosis | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8.1 1 day versus 2 day policy after transurethral resection of prostate | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 9 Epidiymitis | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9.1 3 day policy versus 28 day policy after urethrotomy | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 10 Recurrence of strictures at 6 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10.1 3 day policy versus 28 day policy after urethrotomy | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 11 Recurrence of strictures at 12 months | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 11.1 3 day policy versus 28 day policy after urethrotomy | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 12 Recurrence of strictures (no time frame) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 12.1 1 day policy versus 14 day policy after urethrotomy (outcome assessed using flow rate) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 12.2 1 day policy versus 14 day policy after urethrotomy (outcome assessed using urethrography) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 13 Long term urinary complications (unspecified) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 13.1 1 day versus 5 day policy after rectal resection | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 14 Post operative fever | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 14.1 Immediate removal policy after hysterectomy versus 1 day later policy | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15 Length of hospitalisation | 3 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 15.1 Following TURP | 2 | 168 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.20 [‐1.71, ‐0.68] |

| 15.2 Following transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP) | 1 | 104 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.4 [‐3.79, ‐1.01] |

| 15.3 Following retropubic surgery (colposuspension in women) | 1 | 91 | difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.6 [‐1.31, 0.11] |

| 16 Length of hospitalisation | 2 | 146 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.94 [‐2.61, ‐1.27] |

| 16.1 Immediate removal policy versus 1 day policy for urinary retention | 1 | 60 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.10 [‐2.77, 0.57] |

| 16.2 1 day versus 5 day policy after colposuspension | 1 | 86 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.10 [‐2.83, ‐1.37] |

| 17 Length of hospitalisation | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 17.1 1 day versus 5 day policy after anterior colporrhaphy | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 18 Patient dissatisfaction | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 1 Short term urinary retention / delayed voiding after catheter removal.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 2 Number needing to be re‐catheterised.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 3 Chronic urinary retention.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 4 Urinary tract infection.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 5 Urinary Tract Infection (by gender).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 6 Urethral pain and discharge.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 7 Secondary haemorrhage.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 8 Deep venous thrombosis.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 9 Epidiymitis.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 10 Recurrence of strictures at 6 months.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 SHORT VERSUS LONGER DURATION OF CATHETER USE, Outcome 11 Recurrence of strictures at 12 months.

2.12. Analysis.