Abstract

Child care staff are among the lowest wage workers, a group at increased risk for a wide array of chronic diseases. To date, the health of child care staff has been largely ignored and there have been very few interventions designed for child care staff. This paper describes the development of the Caring and Reaching for Health (CARE) Healthy Lifestyles intervention, a workplace intervention aimed at improving physical activity and health behaviors among child care staff. Theory and evidence-based behavior change techniques informed the development of intervention components with targets at multiple social ecological levels. Final intervention components included an educational workshop held at a kick-off event, followed by three 8-week campaigns. Intervention components within each campaign included: 1) an informational magazine, 2) goal setting and weekly behavior self-monitoring, 3) weekly tailored feedback, 4) email/text prompts, 5) center-level displays that encouraged team-based goals and activities, and 6) coaching for center directors. This multi-level, theory-driven intervention is currently being evaluated as part of a larger randomized controlled trial. Process evaluation efforts will assess the extent to which child care staff participated in, engaged with, and were satisfied with the intervention. Lessons learned will guide future intervention research engaging child care workers.

BACKGROUND

Low-wage workers, especially those from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds, face disproportionately high rates of chronic disease and have lower life expectancies (Kanjilal et al., 2006; Singh & Siahpush, 2006). The United States (U.S.) child care workforce (1.3 million individuals, 40% of whom are racial and ethnic minorities) are among the lowest wage workers in the U.S., earning a median hourly wage of $9.77 ($20,320 salary/year) (Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, 2016; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017). Child care staff are at increased risk for overweight and obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes, compared to women employed in other sectors (Linnan et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2013; Whitaker, Becker, Herman, & Gooze, 2013). In fact, a recent study found that over two-thirds (66.3%) of child care staff in North Carolina were obese (Linnan et al., 2017), compared to 40.4% of adult women in the U.S. (Flegal et al., 2016). In addition, child care staff face elevated levels of emotional distress (Linnan et al., 2017) and multiple high-risk health behaviors (Tovar et al., 2016). While child care staff are increasingly called upon to be healthy role models as part of childhood obesity prevention efforts (CDC, 2017a), very little attention has been paid to their personal health.

Comprehensive worksite health promotion programs have been shown to improve employee health outcomes (e.g., body mass index (BMI), blood pressure), promote healthy lifestyle behaviors (e.g., smoking cessation, physical activity, diet), increase job satisfaction, and improve productivity (Osilla et al., 2012; Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2010). However, like other small workplaces, child care centers do not typically offer any type of health promotion program, policy, or environmental support for their employees (Harris, Hannon, Beresford, Linnan, & McLellan, 2014). In the literature, we came across only one quasi-experimental study and one pilot study engaging child care staff in workplace health promotion, but otherwise this population and workplace have largely been ignored. Caring and Reaching for Health (CARE, grant # R01-HL119568) is an ongoing intervention study evaluating the impact of a newly developed workplace health promotion program for child care staff. Study design and protocols for the CARE cluster-randomized trial have been published elsewhere (Ward, under review). This paper describes the development of CARE’s Healthy Lifestyles intervention, which was designed to increase physical activity and improve health behaviors of child care staff. To ensure specificity of intervention reporting, we adhere to the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) guidelines (Hoffmann et al., 2014) and follow the recommendations from the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) (Albrecht, Archibald, Arseneau, & Scott, 2013).

METHODS

Study Design

CARE is a cluster-randomized trial involving 56 child care centers and 553 child care staff across seven moderate-to-low income counties in North Carolina, each demographically representative of the state population. Participants were randomized by center into either the Healthy Lifestyles (intervention) or Healthy Finances (attention control) arm. Data are collected at baseline (prior to randomization and intervention start), six months (immediately postintervention), and 18 months (12 months post-intervention to assess maintenance). The primary outcome for the study is child care workers’ physical activity (measured via accelerometry); secondary outcomes include other health behaviors (e.g., diet, weight, smoking), physical health indicators (e.g., BMI, blood pressure, fitness tests), and workplace health and safety environment (e.g., general infrastructure, organizational policies and practices, programs and promotions, internal physical and social environment). The reason physical activity was chosen as the primary outcome of interest is twofold. First, it is well documented that increasing physical activity can have a positive impact on other health outcomes (e.g., weight, blood pressure, stress). Second, physical activity interventions can be low-cost and require minimal resources, making them ideal for this population (low wage workers) in a child care setting. The study protocol was approved by the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill institutional review board.

Intervention Development

Theoretical Foundations of the Intervention

Development of the Healthy Lifestyles intervention was guided by the social ecological framework (SEF), which posits that multiple levels of influence work independently and interdependently to influence individuals’ behaviors, and that interventions engaging more levels of the SEF will yield better outcomes (Sallis, Owen, & Fisher, 2008; Stokols, Allen, & Bellingham, 1996). This workplace-based intervention addressed the following SEF levels and targets: intrapersonal (child care staff), interpersonal (interactions between staff), and organizational (center health-related programs, policies, and environmental supports).

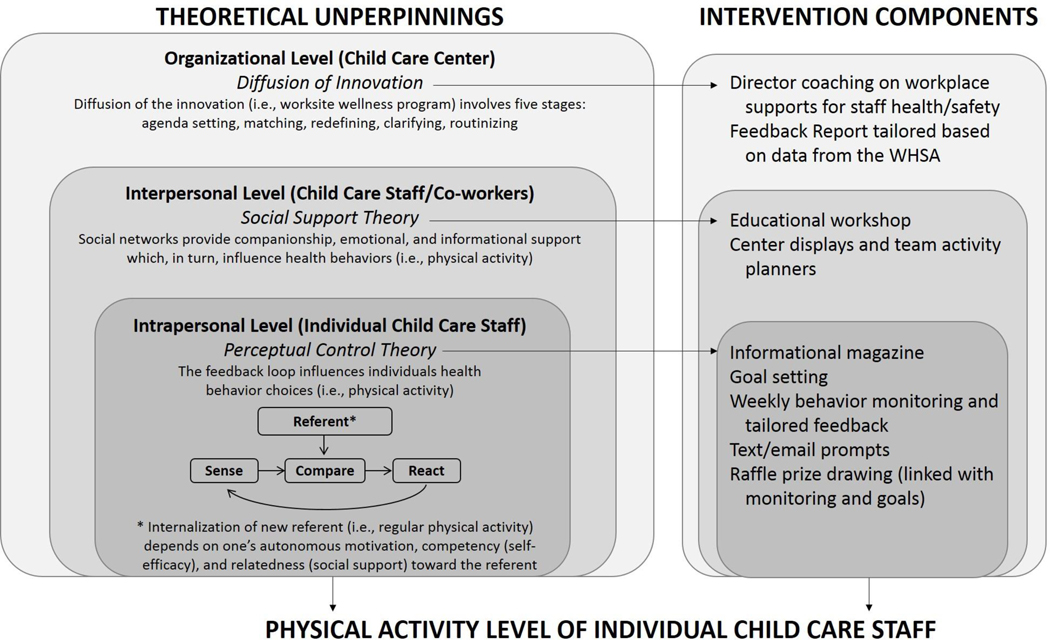

As shown in the conceptual model (Figure 1), a specific theory was matched to each level to identify drivers of behavior change. These included Perceptual Control Theory (intrapersonal), Social Support Theory (interpersonal), and Diffusion of Innovation Theory (organizational). Behavior change techniques (BCTs) (Abraham & Michie, 2008; Michie et al., 2013) associated with each theory were also identified and incorporated into intervention components. BCTs are highlighted in text by “BCT #” and are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of the CARE Healthy Lifestyles Intervention

Table 1.

Behavior Change Techniques Guiding Intervention Components

| SEF Level | Theory | Intervention Component | BCT No. & Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Perceptual Control Theory | Kick-off event educational workshop | 1.2 - Problem solving 1.4 - Action planning 1.6 - Discrepancy between current behavior and goal 2.2 - Feedback on behavior 4.1 - Instruction on how to perform a behavior |

| Informational magazine | 1.4 - Action planning 3.1 - Social support (unspecified) 3.2 - Social support (practical) 3.3 - Social support (emotional) 4.1 - Instruction on how to perform a behavior 5.1 - Information about health consequences 8.2 - Behavior substitution |

||

| Goal setting | 1.1 - Goal setting - behavior | ||

| Weekly behavior self-monitoring | 2.3 - Self-monitoring of behavior | ||

| Weekly tailored feedback | 1.5 - Review behavior goals 1.6 - Discrepancy between current behavior and goal 2.2 - Feedback on behavior 8.7 - Graded tasks |

||

| Email/text prompts | 7.1 - Prompts/cues | ||

| Interpersonal | Social Support Theory | Kick-off event educational workshop | 3.1 - Social support (unspecified) 3.2 - Social support (practical) 3.3 - Social support (emotional) |

| Center-level displays | 1.4 - Action planning 3.1 - Social support (unspecified) 3.2 - Social support (practical) 3.3 - Social support (emotional) 7.1 - Prompts/cues |

||

| Organizational | Diffusion of Innovation Theory | Director coaching | 1.1 - Goal setting - behavior 1.2 - Problem solving 1.3 - Goal setting - outcome 1.4 - Action planning 12.1 - Restructuring the physical environment |

For the intrapersonal level, Perceptual Control Theory (PCT) (Powers, 1973) suggests that child care staff behaviors are influenced by a “feedback loop” in which they are constantly perceiving their current condition, comparing it against some referent or desired outcome (e.g., health and well-being), and adjusting their behavior to bring their current condition closer to this referent. BCTs that facilitate this feedback loop include goal setting, self-monitoring, receiving feedback, and reviewing relevant goals in light of feedback. A meta-analysis of physical activity and nutrition interventions among adults found that interventions with self-monitoring and at least one additional technique were most effective in improving physical activity (effect size of 0.38 vs. 0.27 for interventions with only self-monitoring or other PCT-derived technique) (Michie, Abraham, Whittington, McAteer, & Gupta, 2009). Based on this evidence, the Healthy Lifestyles intervention incorporated goal setting, self-monitoring, and tailored feedback BCTs to drive this feedback loop. In addition, behavior substitution and action planning BCTs were incorporated to further support behavior change.

For the interpersonal level, Social Support Theory (Israel, 1985) identifies multiple types of support that individuals within a social network (e.g., staff within a center) can offer one another, including: emotional (e.g., empathy, caring), instrumental (e.g., tangible aid), informational (e.g., advice, suggestions), or companionship. Social support for physical activity has been positively correlated with physical activity outcomes, especially among African-American women (Baskin et al., 2011). In fact, the U.S. Community Preventive Services Task Force strongly recommends social support interventions in community settings such as worksites (Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2002). Given this evidence, the Healthy Lifestyles intervention incorporated several social support BCTs (i.e., general, practical, and emotional social support) into activities to foster team building among child care staff within each center. Key messages encouraged team exercise activities to cultivate social support among staff.

For the organizational level, diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 1995) provides guidance as to the process through which an innovation, such as staff health and well-being, can be disseminated, adopted, implemented, and eventually maintained in a particular setting (e.g., child care setting). BCTs related to goal setting, action planning, problem solving, and restructuring the physical and social environment reinforced center-level activities aimed at improving worker and workplace health.

Pilot Work

An abbreviated version of the Healthy Lifestyles intervention was developed and piloted with child care staff to evaluate acceptability and initial efficacy. The first pilot (November-December 2011) was conducted with 3 child care centers and 17 staff, while the second pilot (April-June 2013) was conducted with 7 child care centers and 66 staff (Hanson, Vaughn, Mazzucca, & Erinosho, 2012). In both pilots, the intervention was launched with a wellness fair and educational workshop, which was followed by a 5–6 week health and wellness campaign that included goal setting, weekly behavior monitoring, weekly tailored feedback, encouragement of team activities, and a coaching visit with the center director.

Results from these pilots demonstrated feasibility and initial efficacy of the intervention. In the first pilot, 100% of staff completed daily behavior self-monitoring forms and submitted those forms weekly for all five weeks. In the second pilot, behavior self-monitoring compliance ranged from a high of 77% (week 1) to a low of 52% (week 3). Across both pilots, the majority of center directors and staff were satisfied with the program, and said they would recommend this type of program to other child care staff. Outcomes data showed a decrease in BMI (−0.2 to −0.8 kg/m2), increases in physical activity (+3191 to 3496 steps/day) and fruit/vegetable intake (+2.1 to 2.6 servings/day), along with a decrease in smoking (−3 to −6.5 cigarettes/day). These pilots provided initial evidence and support for developing CARE’s Healthy Lifestyles intervention.

Healthy Lifestyles Intervention Components

CARE’s Healthy Lifestyles intervention was 6 months in duration and structured to include a kick-off event and educational workshop, followed by three 8-week campaigns. Intervention components within each campaign included: an informational magazine, goal setting through the CARE website, weekly behavior self-monitoring, weekly tailored feedback, weekly email/text prompts, prize raffles for self-monitoring and goal attainment, center-level displays that encouraged team-based goals and activities, and director coaching (i.e., one-on-one coaching provided to the child care center director to implement center-level supports).

Kick-off Event and Educational Workshop.

Participating center directors and staff were required to attend a kick-off event held on a Saturday at a local venue in order to be randomized. The morning portion of the event included a healthy breakfast, physical fitness assessments, pampering stations (e.g., massage, yoga, nail treatments, make-up), health and wellness stations featuring local community resources, and a healthy lunch. Randomization occurred at lunch and was followed by a 90-minute educational workshop (described below). Two separate educational workshops were provided, one for Healthy Lifestyles and another for Healthy Finances (for those randomized into the control arm). No additional interactions happened between intervention and control arm participants after they were randomized.

The Healthy Lifestyles educational workshop targeted both intrapersonal and interpersonal levels. Content focused on increasing participants’ awareness of their current health behaviors compared to national recommendations, provided an overview of the intervention and how it would support healthy behavior changes, and began to build social support among staff at each center. Participants received a detailed feedback report about their current health habits based on information collected prior in their baseline Carolina Health Assessment and Resource Tool (CHART) health surveys (https://chart.unc.edu/) (BCT 1.6: Discrepancy between current behavior and goal; 2.2: Feedback on behavior). CHART surveys assessed physical activity, dietary intake, tobacco and e-cigarette use, sleep habits, emotional health, and psychosocial determinants of these behaviors (self-efficacy, readiness to change, barriers, and social support). The CHART feedback report compared current behaviors to national guidelines (e.g. “referent” in PCT feedback loop) and offered recommendations for making healthy changes. The interventionist guided participants through the CHART feedback report, facilitated a discussion of common barriers to physical activity and the benefits of a healthy lifestyle, helped the group brainstorm specific strategies for increasing physical activity, and introduced a team activity planner (BCT 1.2: Problem solving; 1.4: Action planning; 3.1–3.3: Social support – unspecified, practical, emotional). An overview of the three campaigns was provided, including the materials and tools available to help set goals and monitor progress. Participants were given a pedometer and were trained to use it to track their physical activity steps (BCT 4.1: Instruction on how to perform a behavior). Center teams worked together to personalize a center visual (team poster) to be displayed at the center (described below).

Campaign Themes.

Center staff participated in three 8-week health and wellness campaigns. The primary message of each campaign focused on physical activity, but those messages were used as a gateway to addressing other behaviors. This integration was illustrated by the three campaign themes: 1) Every Little Move Counts! (how to incorporate physical activity into daily life), 2) Balance Your Menu with Movement (how to balance energy in and out for weight maintenance), and 3) Moving for a Healthy Life (how to reduce stress and maintain healthy lifestyle changes).

Informational Magazine.

At the start of each campaign, participants received a campaign-specific issue of the CARE Healthy Lifestyles magazine (Figure 2), content of which reinforced key campaign messages related to physical activity and other health behaviors and targeted both the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels. Articles offered information about potential health benefits (BCT 5.1: Information about health consequences), instruction and guidance on health behaviors (BCT 4.1: Instruction on how to perform a behavior), as well as practical tips and strategies for changing behavior (8.2: Behavior substitution), planners (BCT 1.4: Action planning), and prompts to engage family, friends and coworkers for support (BCTs 3.1–3.3: Social support). The magazine was modeled on the aesthetic look and feel of commercial women’s magazines. To increase appeal and relevancy, photographs in the magazine represented women of diverse race, ethnicity, age, and body type. Additionally, focused interviews with child care providers informed the tone and content.

Figure 2:

CARE Healthy Lifestyles Magazines (Covers and Sample Inserts)

Personal Goal Setting, Self-Monitoring, Tailored Feedback, Prompts, and Raffle.

The goal setting, self-monitoring, and tailored feedback components targeted primarily the intrapersonal level and were intended to drive the PCT feedback loop. These activities were facilitated through the CARE Healthy Lifestyles website. During week 1 of each campaign, participants were asked to set personal goals (BCT 1.1: Goal setting - behavior), including one goal related to steps per day and one additional self-selected health behavior. During weeks 2–7, participants monitored and logged steps and their self-selected health behavior (BCT 2.3: Self-monitoring of behavior). The website sent weekly text/email prompts to remind participants to enter their self-monitoring data (BCT 7.1: Prompts/cues). At the end of each week, the website sent tailored feedback to participants via text/e-mail that reported on goal achievement (BCT 1.5 Review behavior goals; 1.6: Discrepancy between current behavior and goal; 2.2: Feedback on behavior), offered tips for physical activity and the self-selected health behavior goal, and offered a new steps goal based on performance from the previous week. Adjustment of the step goal was based on an algorithm that gradually increased toward a goal of 10,000 steps/day (physical activity recommendations set forth by CDC) (CDC, 2017b) (BCT 8.7: Graded tasks), but also accounted for whether the previous week’s goal was met. In addition, the website sent prompts or tips about physical activity via text/email on a biweekly schedule (BCT 7.1: Prompts/cues).

The website was designed to provide professional-looking and user-friendly web-based tools and resources focused on physical activity and other health behaviors (e.g., links to CDC educational resources); however, participants without computer or smart-phone access received assistance via telephone. To encourage goal setting and self-monitoring, research assistants conducted check-in visits during the first week of each campaign to troubleshoot any challenges to using the web-based tools. To further encourage self-monitoring, prize raffles were held at the end of each campaign. Participants who monitored goals regularly (≥3 days/week for 5 of 6 weeks per campaign) earned one entry into a prize drawing raffle; and participants who met goals (4 of 6 weeks per campaign) earned an additional entry into a prize raffle. Campaign raffles for those who met steps goals were separate from the raffles for the self-selected health behavior goal.

Center-level Displays.

Center-level displays were designed to target the interpersonal level, and each campaign provided new visual materials to update the CARE Healthy Lifestyles team poster, created by participants during the kick-off educational workshop. Centers were encouraged to display their poster in an area where participating staff were likely to see and interact with it, thereby serving as a visual reminder or “cue to action” (BCT 7.1: Prompts/cues). As shown in Figure 3, the display offered space for a team photo (taken at the kick-off event), which was delivered to the center at the check-in visit during the first campaign. The display also had space for weekly motivational inserts in the “Motivational Corner.” Messages spoke to the benefits of physical activity and strategies to engaging in goal-related activities (e.g., “Exercise can boost your mood. Tame stress with a brisk 10-minute walk”). Motivational inserts also contained 1–2 blank pages, upon which participants wrote their own messages. There was also space for the team to post their team activity planner (BCT 1.4: Action Planning). The activity planner form provided space for staff to post and track weekly activity goals that they could do as a team. Publicly committing to being active was expected to increase team engagement and provided social support to increase participants’ level of physical activity (BCTs 3.1–3.3: Social support). In the center of the team poster is the “Goals Tree” which participants could adorn with “goal hearts,” paper hearts printed with the goals included in the self-monitoring system. These pre-printed “goal hearts” were provided at the start of each campaign (blank hearts were also included for personalized goals) and further reinforced the importance of goal setting.

Figure 3:

Center-Level Display (Lay-out and Instructions for Participants)

Director Coaching.

Center directors received coaching on implementing and sustaining a healthy work environment as a strategy to target the organizational level. The first session was provided in-person at the child care center, the second and third sessions were provided via telephone. During these sessions, the interventionist reviewed and built upon a tailored feedback report (“Director Feedback Report”). Initially, this feedback report was based on results from the baseline Workplace Health and Safety Assessment (WHSA) tool, an assessment of the center’s general infrastructure, organizational policies and practices, programs and promotions, internal physical and social environment. The feedback report was used to facilitate a discussion between the interventionist and center director about successes, challenges, and next steps to build infrastructure (e.g., develop a wellness leadership team), policy (e.g., written policy prohibiting tobacco use), programmatic (e.g., center-wide fitness breaks held in classroom), or environmental supports (e.g., addition of water and fresh fruit in breakroom) for staff health (BCT 1.1: Goal setting - behavior; 1.2: Problem Solving; 1.3: Goal setting - outcome; 1.4: Action planning; 12.1: Restructuring the physical environment). Following each session, the director received a summary of issues discussed via email. Centers were also encouraged to organize a wellness leadership team (center director, plus 1 or 2 staff) or “wellness champions” as a way to increase “buy-in” for health programming as well as to disperse time and effort required to sustain the program across multiple people (Michaels & Greene, 2013). At the end of the intervention, the director received a final feedback report, compiling notes from all three coaching sessions, recommendations for changes, as well as referrals to local, state, and national resources, such as worksite wellness challenges and ideas available on the “Eat Smart, Move More North Carolina” website (http://eatsmartmovemorenc.com/), along with a summary of the follow-up WHSA.

Evaluation of the Healthy Lifestyles Intervention

The effectiveness of the Healthy Lifestyles intervention is being evaluated as part of the larger CARE study, documenting changes in staff physical activity (primary outcome) and other health behaviors (e.g., diet, weight, smoking, sleep), as well as health-supportive work environment. Changes are being evaluated against an attention control (Healthy Finance), details of which will be described elsewhere. This study also includes a thorough process evaluation plan per Linnan and Steckler (2002). Process data are collected for each intervention component (i.e., educational workshop, informational magazines, goal setting, self-monitoring, tailored feedback, prompts, center displays, director coaching) using a combination of observation tools, participant and director evaluation surveys, and project tracking records. Findings will reveal how many center staff engaged with the intervention and for whom and under what conditions the intervention is most effective.

DISCUSSION

CARE’s Healthy Lifestyles intervention fills a critical gap in the workplace health and safety literature as the first workplace-based, multi-level, theory-guided intervention designed to increase physical activity and improve other healthy behaviors among child care staff. Prior to CARE, there were only one quasi-experimental and one pilot studies that included a focus on the health of child care staff. The quasi-experimental study was conducted in 13 child care centers in California and targeted child care staff (Gosliner et al., 2010). That intervention included a kick-off training, monthly newsletters, and a walking program. It produced a significant but very modest decrease in sugar-sweetened beverage intake only. The pilot study focused partially on staff health (Herman, Nelson, Teutsch, & Chung, 2012). The intervention applied a theory-guided curriculum aimed at obesity prevention among staff, children, and parents; and it yielded a reduction in BMI among all participants in the pilot study. Despite the lack of attention to child care staff health in the literature, the importance of staff health is receiving increased attention as evidenced by a recent call to action from Child Care Aware, the leading provider of technical assistance to child care program in the U.S. (Child Care Aware, 2017). Interventions focused on child care staff may improve the health of child care workers and, potentially the health of children in their care.

Given the scarcity of prior work, our intervention development process built upon lessons learned from the broader workplace health and safety literature and our pilot work. A recent meta-analysis revealed that theory-guided workplace interventions are more effective than interventions with less defined theoretical underpinnings (Taylor, Conner, & Lawton, 2012). Applying theory into intervention development required careful consideration and selection of theoretical models and behavior change techniques to target specific behavioral change processes and generate effective behavior change (Abraham & Michie, 2008; Michie et al., 2013; Tate et al., 2016). The pilot work then confirmed the feasibility and initial efficacy of intervention components. The resulting Healthy Lifestyles intervention thus represents a multi-level, theory-driven approach that is also tailored to the unique characteristics of the child care staff within the center context.

Like other small workplaces, child care centers are likely to face challenges to implementing workplace health programs due to limited capacity, time, and resources (Hannon et al., 2012). Furthermore, child care staff face emotionally and physically demanding work, while center directors must manage staff turn-over, scheduling, and meeting child care regulations (Totenhagen et al., 2016). Thus, many components of the intervention were delivered directly to the child care staff (e.g., informational magazines, tailored feedback), requiring little from the center or the center director. Yet, changes are more likely to happen and be sustained if there are workplace supports for healthy changes in child care staff. Thus, the goal of providing one-onone coaching sessions to directors was to build upon existing strengths and resources, help directors develop an action plan and solve potential challenges, and make connections with local, state, and national workplace health and safety resources that could be sustained after the intervention. In addition, recommended strategies included feasible and low-cost options, such as organizing walks during breaks, providing inexpensive equipment for physical activity (e.g., hand weights, resistance bands), and/or making infused water or healthy snacks available for staff. While intervening with low wage worker in child care centers is challenging, it is an important population that is suffering from many health problems that can be addressed through workplace health and safety programs.

CONCLUSION

The Caring and Reaching for Health (CARE) Healthy Lifestyles intervention is a theory-driven, multi-level workplace health and safety intervention aimed at improving health behaviors among low-wage, high-risk child care staff and creating a healthy work environment. Findings from this intervention will inform future health promotion efforts in early care and education settings.

Contributor Information

Dr Gabriela Arandia, Health Behavior at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in Chapel Hill, North Carolina..

Mrs Amber E. Vaughn, Children’s Healthy Weight Research Group at the Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in Chapel Hill, North Carolina..

Mrs Lori A. Bateman, Collaborative Studies Coordinating Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in Chapel Hill, North Carolina..

Dr Dianne S. Ward, Nutrition in the Gillings School of Global Public Health and Director of the Children’s Healthy Weight Research Group at the Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina..

Dr. Laura A. Linnan, Health Behavior in the Gillings School of Global Public Health University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina..

REFERENCES

- Abraham C, & Michie S (2008). A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27(3), 379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, & Scott SD (2013). Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations. Implementation Science, 8(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin ML, Gary LC, Hardy CM, et al. (2011). Predictors of retention of African American women in a walking program. American Journal of Health Behavior, 35:40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2017a. Early Care and Education (ECE). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/strategies/childcareece.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2017b. Physical Activity. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/

- Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. University of California, Berkeley; 2016. Retrieved from: http://cscce.berkeley.edu/files/2016/Early-Childhood-Workforce-Index-2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Child Care Aware. 2017. Retrieved from: http://usa.childcareaware.org//wpcontent/uploads/2017/03/Staff-wellness-white-paper.pdf

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. (2016). Journal of the American Medical Association, 315, 2284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosliner WA, James P, Yancey AK, Ritchie L, Studer N, Crawford PB (2010). Impact of a worksite wellness program on the nutrition and physical activity environment of child care centers. American Journal of Health Promotion, 24:186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR, Hannon PA, Beresford SA, Linnan LA, McLellan DL (2014). Health promotion in smaller workplaces in the United States. Annual Review of Public Health, 35:327–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon PA, Garson G, Harris JR, Hammerback K, Sopher CJ, & Clegg-Thorp C (2012). Workplace Health Promotion Implementation, Readiness, and Capacity Among Mid-Sized Employers in Low-Wage Industries: A National Survey. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine/American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 54(11), 1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson P, Vaughn A, Mazzucca S, Erinosho T, Ward DS (2012). Getting Healthy for the Holidays: Results from a worksite wellness intervention for childcare center staff in North Carolina International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. Austin, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Herman A, Nelson BB, Teutsch C, Chung PJ (2012). “Eat healthy, stay active!”: a coordinated intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity among head start parents, staff, and children. American Journal of Health Promotion,27:e27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, … & Lamb SE (2014). Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. British Medical Journal, 348, g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA (1985). Social networks and social support: implications for natural helper and community level interventions. Health Education Quarterly,12:65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanjilal S, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Zhang P, Nelson DE, Mensah G, Beckles GL (2006). Socioeconomic status and trends in disparities in 4 major risk factors for cardiovascular disease among US adults, 1971–2002. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(21):2348–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan L, Arandia G, Bateman LA, Vaughn A, Smith N, & Ward D (2017). The Health and Working Conditions of Women Employed in Child Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan L, & Steckler A (2002). Process evaluation and public health interventions: An overview In: Steckler A, and Linnan L (Eds.), Process Evaluation in Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; (pgs. 1–23). [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, … & Wood CE. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Abraham C, Whittington C, McAteer J, Gupta S (2009). Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: a meta-regression. Health Psychology, 28:690–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels CN, & Greene AM (2013). Worksite wellness: Increasing adoption of workplace health promotion programs. Health Promotion Practice, 1524839913480800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osilla KC, Van Busum K, Schnyer C, Wozar Larkin J, Eibner C, Mattke S (2012). Systematic review of the impact of worksite wellness programs. American Journal of Managed Care. 2012;18:e68–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers WT Behavior: The Control of Perception. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E Diffusion of Innovations, 5th Edition. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis JF, Owen N, & Fisher EB (2008). Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4, 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Siahpush M (2006). Widening socioeconomic inequalities in US life expectancy, 1980–2000. International Journal of Epidemiology 2006, 35(4):969–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Dortch KS, Byrd-Williams C, Truxillio JB, Rahman GA, Bonsu P, & Hoelscher. (2013). Nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes, and dietary behaviors among head start teachers in Texas: A cross-sectional study. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113, 558–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D, Allen J, & Bellingham RL (1996). The social ecology of health promotion: implications for research and practice. American Journal of Health Promotion, 10(4), 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. (2010). Recommendations for worksite-based interventions to improve workers’ health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(2), S232–S236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. (2002). Recommendations to increase physical activity in communities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22(4), 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate DF, Lytle LA, Sherwood NE, Haire-Joshu D, Matheson D, Moore SM & Michie S (2016). Deconstructing interventions: approaches to studying behavior change techniques across obesity interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor N, Conner M, & Lawton R (2012). The impact of theory on the effectiveness of worksite physical activity interventions: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Health Psychology Review, 6(1), 33–73. [Google Scholar]

- Totenhagen CJ, Hawkins SA, Casper DM, Bosch LA, Hawkey KR, & Borden LM (2016). Retaining Early Childhood Education Workers: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(4), 585–599. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar A, Vaughn A, Grummon A, Burney R, Erinosho T, Østbye T, & Ward D Family child care home providers as role models for children: Cause for concern? Preventive Medicine Reports. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Childcare Workers. 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/personal-care-and-service/childcareworkers.htm

- Whitaker RC, Becker BD, Herman AN, Gooze RA (2013).The physical and mental health of Head Start staff: the Pennsylvania Head Start staff wellness survey, 2012. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2013;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]