Abstract

Background & Aims

Acute liver failure as the initial presentation of Wilson’s disease is usually associated with onset in childhood, adolescence or early adulthood. Outcomes after transplantation for late-onset presentations, at or after 40 years, are seldom reported in the literature.

Methods

We report a case, review the literature and provide unpublished data from the UK Transplant Registry on late-onset acute liver failure in Wilson's disease.

Results

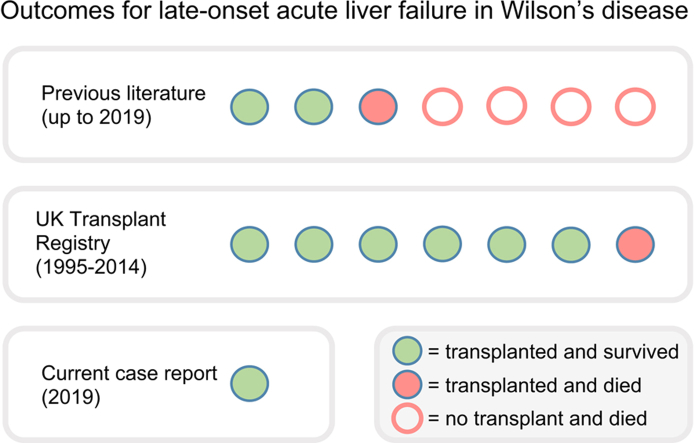

We describe the case of a 62-year-old man presenting with acute liver failure who was successfully treated with urgent liver transplantation. We identified 7 cases presenting at age 40 years or over in the literature, for which individual outcomes were reported; 3 were treated with transplantation and 2 survived. We identified a further 8 cases listed for transplantation in the UK between 1995 and 2014; 7 were treated with transplantation and 6 survived. One patient was de-listed for unknown reasons.

Conclusions

Wilson's disease should be considered in older adults presenting with acute liver failure. We suggest that urgent liver transplantation has good outcomes for late-onset presentations and recommend that urgent transplantation should always be considered in Wilson's disease presenting as acute liver failure.

Lay summary

Wilson's disease is a rare inherited disease that causes copper accumulation in the liver and brain and usually manifests during childhood, adolescence or early adulthood. We report the case of a 62-year-old who developed acute liver failure and was successfully treated with urgent liver transplantation. We discuss the outcomes of other late-onset cases of acute liver failure due to Wilson's disease in the literature and provide additional data from the UK Transplant Registry.

Keywords: Wilson's disease, hepatolenticular degeneration, liver failure, liver transplantation

Abbreviations: ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; ALF, acute liver failure; INR, international normalised ratio; KF, Kayser-Fleischer; NHSBT, NHS blood and transplant; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplant Network; WD, Wilson's disease

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We describe the case of a 62-year-old transplanted for acute liver failure in Wilson's disease.

-

•

Outcomes after transplantation were previously reported in 3 late-onset cases.

-

•

We describe a further 7 late-onset cases from the UK Transplant Registry.

-

•

Wilson's disease should be considered in acute liver failure presenting at any age.

-

•

Transplantation should always be considered in acute liver failure presentations.

Introduction

Wilson's disease (WD) is an autosomal-recessive disorder of copper metabolism caused by ATP7B mutations.1 It presents with a range of hepatic, neurological and psychiatric manifestations.2 Acute liver failure (ALF) is a life-threatening presentation of WD that is invariably fatal without transplantation. In this context, it refers to an acute liver injury associated with hepatic encephalopathy as a de novo presentation of WD.3

The majority of WD cases present between the ages of 5 and 35 years. Late-onset neurological and hepatic presentations, defined as those presenting at or after 40 years, are described however late-onset ALF is rare and outcomes are seldom reported.

Case report

A 62-year-old male presented with a 4-week history of progressive exercise intolerance, leg swelling, steatorrhea and weight loss. He had no significant past medical, family, drug or alcohol history. On examination there was hepatic fetor and peripheral oedema without jaundice, ascites, encephalopathy or signs of chronic liver disease. The neurological examination was unremarkable. Kayser-Fleischer (KF) rings were not visible at the bedside.

Initial investigations revealed bilirubin 40 μmol/L, alanine aminotransferase 130 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase 211 IU/L and alkaline phosphatase 168 IU/L. There was a coagulopathy with an international normalised ratio (INR) of 2.5. The full blood count and renal profile were unremarkable with C-reactive protein 17 mg/L. A biochemical and serological screen for liver disease, including serum caeruloplasmin and copper, was sent. CT scanning after admission revealed mild ascites without other evidence of portal hypertension. At this stage the differential diagnosis remained wide and the patient was mobilising independently with normal observations.

On further investigation ultrasound revealed cirrhotic appearances of the liver with portal vein thrombosis, and gastroscopy identified grade 1 oesophageal varices. Serological testing for viral and autoimmune disease was negative. Preliminary histopathology from a percutaneous liver biopsy (performed after fresh frozen plasma infusion) suggested florid acute inflammation.

During the course of these investigations the patient developed visible jaundice and slurred speech. In retrospect, he reported bilateral upper limb tremor and difficulty writing. Over the ensuing days the serum bilirubin increased from 94 to 483 μmol/L. The combination of mixed conjugated and unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia, reticulocytosis and undetectable serum haptoglobins suggested haemolysis. The INR increased to 6.1. The patient, now in his second week of admission, became encephalopathic. He rapidly deteriorated while awaiting transfer to a liver transplant unit and was intubated and ventilated. He was then transferred and listed for ‘super-urgent’ liver transplantation, which he received from a donor after brain death (DBD), 24 hours later.

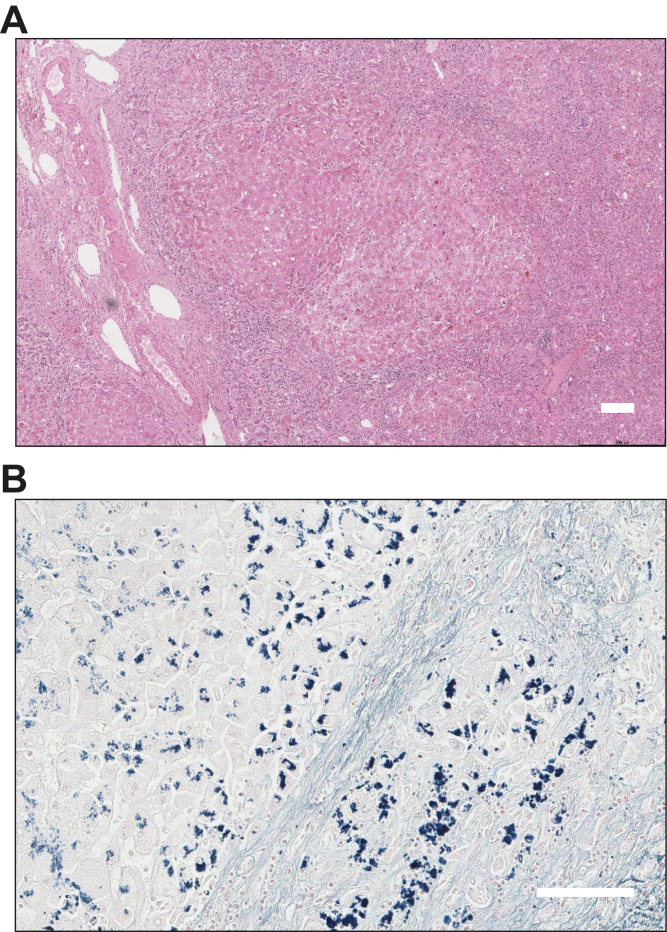

At the time of transfer, additional histopathological findings became available (Fig. 1); there was mildly active cirrhosis with abundant copper deposition and cholestasis suggestive of decompensated WD. The copper content was 1,753 μg/g. Bloods sent at admission revealed a low serum caeruloplasmin 0.13 g/L and normal serum copper 16.7 μmol/L. The calculated non-caeruloplasmin-bound copper was significantly raised at 10.3 μmol/L. 24-hour urine collection and slit lamp examination were not performed. Genetic analysis identified compound heterozygous mutations in the ATP7B gene (c.2108G>A, p.(Cys703Tyr); c.2804C>T, p.(Thr935Met)).

Fig. 1.

Histopathological findings from the percutaneous liver biopsy.

(A) Low power H&E stain demonstrating cirrhosis with broad fibrous septa and prominent perisinusoidal and pericellular fibrosis. The parenchyma shows extensive cellular and canalicular cholestasis with large cell and oxyphilic change and minimal steatosis. (B) Victoria blue preparation showing abundant hepatocellular copper-associated protein deposition. Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

The patient had a complicated post-operative course after developing pulmonary and cerebral aspergillosis. He was discharged home after an 8-week admission. Two years later he is asymptomatic, with normal graft function, except for subtle balance impairment. At follow-up, he mentioned that he had started taking whey protein supplements several days per week around a decade prior to his presentation.

Materials and methods

Literature search

We identified cases of WD presenting with late-onset ALF from the literature by searches of PubMed prior to 1 August 2019. Late-onset cases were defined as those presenting at or after age 40 years. The search terms “Wilson's disease” and “Wilson disease” in combination with “acute liver failure”, “fulminant liver failure”, “transplant” and “transplantation” were used. Cohort studies, case series and individual case reports were reviewed. Cases where undiagnosed symptoms of WD preceded the ALF presentation by more than 6 months were excluded. Demographics, treatments, outcomes and copper indices were recorded, where possible. The serum non-caeruloplasmin-bound copper levels were calculated.

NHS blood and transplant (NHSBT) data

The UK Transplant Registry was examined for cases listed with a primary diagnosis at registration of “Acute hepatic failure - Wilson's disease” or “Wilson's disease” in combination with a ‘super-urgent’, as opposed to ‘elective’ listing. Demographics, treatments, intervals to transplantation and outcomes were recorded for those patients age 40 years or over.

Results

Late-onset hepatic and neurological presentations of WD have been studied in a large international cohort. Ferenci et al. described the clinical features of 46 of 1,223 (3.8%) cases of WD from Europe that presented over the age of 40 years.4 This included patients presenting up to the age of 58 years. There were 15 hepatic presentations, including only 1 patient who presented with ALF for whom further information was not available.

Cohorts of patients requiring liver transplantation confirm that late-onset ALF in WD is rare. Arnon et al. reported outcomes for children and adults who had liver transplantation in the United States and Canada between 2002 and 2008. Of 38,715 patients who received transplants there were 51 children and 119 adults with WD. Of these adults, 62 presented with ALF, 9 of whom were age 40 years or over.5 Between the ages 40–49, 50–59 and 60–69 years there were 5, 2 and 2 cases presenting with late-onset ALF, respectively, however individual outcomes for these cases are not available. Late-onset ALF was not reported in other cohorts of patients with WD requiring transplantation.[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]

Several case reports have described the presentation and outcomes for individual patients with WD presenting with late-onset ALF. All 7 cases that we identified were female and the 4 cases that did not receive transplantation died. Two patients, age 54 and 42 years, survived at least 5 years following transplantation,12,13 and another patient, age 44 years, had graft failure due to arterial hypoperfusion, underwent a further transplantation and then died of sepsis.14 These cases, including the serum and urine copper levels at presentation, are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of the demographics, treatment and outcome of individual cases presenting with late-onset ALF in WD from the previous literature, NHSBT data and current case.

| Age | Sex | Tx | Outcome | Cp (g/L) [>0.15] | s-Cu (μmol/L) [11-20] | ncb-Cu (μmol/L)[<2.4] | u-Cu (μmol/day) [>1.6] | Reference/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | F | No | Died | 0.18 | 16.5 | 7.5∗ | 14.1 | Amano et al. 201815 |

| 58 | F | No | Died | 0.12 | 11.4 | 5.4∗ | – | Danks et al. 199016 |

| 54 | F | Yes | Survived | 0.18 | 14.0∗ | 5.1 | 35.7 | Gow et al. 200012 |

| 44 | F | No | Died | 0.14 | 28.0 | 21.1∗ | – | Danks et al. 199016 |

| 44 | F | No | Died | 0.14 | 27.4∗ | 20.5 | – | Gow et al. 200012 |

| 44 | F | Yes | Died | 0.25 | 58.3 | 45.9∗ | 139.3 | Kerber et al. 200314 |

| 42 | F | Yes | Survived | – | – | – | – | Bellary et al. 199313 |

| 55 | F | No | (Delisted) | – | – | – | – | NHSBT registry |

| 45 | F | Yes | Survived | – | – | – | – | NHSBT registry |

| 44 | M | Yes | Survived | – | – | – | – | NHSBT registry |

| 43 | M | Yes | Survived | – | – | – | – | NHSBT registry |

| 41 | F | Yes | Died | – | – | – | – | NHSBT registry |

| 41 | M | Yes | Survived | – | – | – | – | NHSBT registry |

| 40 | M | Yes | Survived | – | – | – | – | NHSBT registry |

| 40 | M | Yes | Survived | – | – | – | – | NHSBT registry |

| 62 | M | Yes | Survived | 0.13 | 16.7 | 10.3∗ | – | Current case |

Abnormal results are highlighted in bold with reference ranges in brackets.

ALF, acute liver failure; Cp, caeruloplasmin; s-Cu, serum copper; ncb-Cu, non-caeruloplasmin-bound copper; NHSBT, NHS blood and transplant; Tx, transplantation; u-Cu, urinary copper output; WD, Wilson's disease.

Denotes biochemical parameters that are calculated from other values.

Data from NHSBT shows that 114 of 17,186 listings for liver transplantation in the UK between 1995 and 2014 were for adult patients with a WD diagnosis. This includes 60 patients with acute and 54 patients with chronic WD presentations. Eight acute presentations were late-onset and, on this basis, approximately 1 in 2,150 patients listed for transplantation had late-onset ALF due to WD. Six of the 8 cases identified were successfully treated with super-urgent transplantation and survived at least 10 years (or remain alive). A 55-year old female was de-listed within 5 days (the reasons for this are unclear) and a 41-year old female died 3 days after transplantation. The procedure was performed within 3 days of listing in all cases except one where the delay was 8 days and the patient survived. These cases are summarised in Table 1.

Discussion

Late-onset ALF is a rare, life-threatening presentation of WD. Our case report, in combination with transplant registry data from the UK over 2 decades, demonstrates the importance of considering WD in older adults presenting with ALF and suggests that outcomes are good for late-onset presentations treated with urgent liver transplantation.

There are several reasons why making the diagnosis of WD in an older adult presenting with ALF can be difficult. First, this presentation is rare and the diagnosis may not be considered; UK guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests from 2017 reflect this and do not include screening for WD on the extended liver aetiology panel in those over 40 years old.17 As with children and young adults, the results of diagnostic tests may be delayed, as in our case, or misleading: the caeruloplasmin may be normal and, given the majority of circulating copper is bound to caeruloplasmin, the total serum copper (typically low in WD) may be normal or elevated (Table 1). The clinician therefore needs to request a urinary copper level using a 24 h collection and calculate the serum non-caeruloplasmin-bound copper, both of which should be markedly elevated.

There may be other important clues to the diagnosis. Our case highlights that neurological features, which may be subtle, can precede or develop concurrently with ALF in WD. Tremor was also noted in an aforementioned case report,15 and we would argue that tremor, drooling or slurred speech emerging prior to the development of encephalopathy are red flags for WD. While performing slit lamp examination may be challenging in critically ill patients, KF rings are seen in up to half of cases presenting with ALF and may be visible at the bedside. An acute and disproportionate rise in bilirubin associated with anaemia, as in our case, is indicative of a concurrent haemolysis and may also provide a vital clue. This complication is common in ALF in WD and associated with worse prognosis.2

The importance of making the diagnosis of WD prior to transplantation should not be underestimated. NHSBT, like the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) in the United States, makes special provision for ALF due to WD when considering the urgency of transplantation and the terminology relating to acute presentations of liver disease become relevant when listing a case of WD. Indeed, 52 of 114 patients listed for transplantation for WD in the UK between 1995 and 2014 required emergency grafting. There is also a need to provide optimal bridging therapy, monitor for complications and family screening.2

There are several definitions for ALF. In general, these refer to a severe acute liver injury that provokes hepatic encephalopathy but vary according to the interval between the onset of jaundice and encephalopathy.3 The pre-requisite that ALF occurs in the absence of pre-existing liver disease does not apply in WD.3 Patients often have radiological or histological evidence of undiagnosed cirrhosis and share the poor prognosis associated with other causes of ALF. Our patient deteriorated with encephalopathy several days after developing jaundice. Some might argue that the non-specific symptoms in the weeks before the patient developed jaundice are more suggestive of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) however, the definition of this entity remains controversial. Many cases of ALF in WD could be re-classified as having ACLF under proposed definitions. This term is not currently used in NHSBT or OPTN policy and has not been widely applied in the WD literature and so our case is characterised as having ALF.

The reason for the unusually high age of onset in our case is unclear. We are not aware of an association between the individual ATP7B mutations and late-onset presentations of WD. Screening for viral infections was negative and the only lifestyle change that we identified was whey protein supplementation over the preceding decade. We can only speculate whether this was relevant in our case: Zinc salts, which are an established treatment for WD, are added to some bodybuilding supplements and could theoretically delay a hepatic presentation of WD.

Importantly, we were able to identify only 3 cases of late-onset ALF in WD treated with transplantation in the pre-existing literature, 2 of whom survived. This case report, in combination with the NHSBT data, describes a further 8 cases. This includes 6 cases presenting in the fifth decade who had good outcomes, more than doubling the number of reported cases. However, we recognise that using transplant registry data to assess outcomes in late-onset ALF in WD has limitations. There may be a selection bias whereby those patients who are not deemed fit for transplantation, and therefore do not survive, are not listed and there may be additional cases of ALF in which the diagnosis of WD was not made prior to death.

To conclude, we have reported one of the latest onsets of ALF in WD, including the successful transplantation of this patient at least 8 years later than any other published case. We have also described unpublished data provided by NHSBT describing a further 8 cases of late-onset ALF in WD. We recommend that the diagnosis of WD should be included in the differential diagnosis of ALF at any age and that urgent transplantation should be considered for late-onset presentations of ALF in WD.

Financial support

SS receives financial support from the Guarantors of Brain and Wilson's Disease Support Group UK for research on Wilson's disease.

Authors' contributions

SS drafted the manuscript. RT and GW provided and analysed data from NHSBT, respectively. AD provided histopathological analysis and prepared the figure. All authors reviewed and amended the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

We would like thank our patient who provided informed consent for publication of this case report and NHS Blood and Transplant who provided data from the UK Transplant Registry.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100096.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Ala A., Walker A.P., Ashkan K., Dooley J.S., Schilsky M.L. Wilson's disease. Lancet. 2007;369:397–408. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shribman S., Warner T.T., Dooley J.S. Clinical presentations of Wilson disease. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:S60. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.04.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendon J., Cordoba J., Dhawan A., Larsen F.S., Manns M., Samuel D. EASL clinical practical guidelines on the management of acute (fulminant) liver failure. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1047–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferenci P., Czlonkowska A., Merle U., Ferenc S., Gromadzka G., Yurdaydin C. Late-onset Wilson's disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1294–1298. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnon R., Annunziato R., Schilsky M., Miloh T., Willis A., Sturdevant M. Liver transplantation for children with Wilson disease: comparison of outcomes between children and adults. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:E52–E60. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng F., Li G.Q., Zhang F., Li X.C., Sun B.C., Kong L.B. Outcomes of living-related liver transplantation for Wilson's disease: a single-center experience in China. Transplantation. 2009;87:751–757. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318198a46e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emre S., Atillasoy E.O., Ozdemir S., Schilsky M., Rathna Varma C.V., Thung S.N. Orthotopic liver transplantation for Wilson's disease: a single-center experience. Transplantation. 2001;72:1232–1236. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200110150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medici V., Mirante V.G., Fassati L.R., Pompili M., Forti D., Del Gaudio M. Liver transplantation for Wilson's disease: the burden of neurological and psychiatric disorders. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1056–1063. doi: 10.1002/lt.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schilsky M.L., Scheinberg I.H., Sternlieb I. Liver transplantation for Wilson's disease: indications and outcome. Hepatology. 1994;19:583–587. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss K.H., Schafer M., Gotthardt D.N., Angerer A., Mogler C., Schirmacher P. Outcome and development of symptoms after orthotopic liver transplantation for Wilson disease. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:914–922. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshitoshi E.Y., Takada Y., Oike F., Sakamoto S., Ogawa K., Kanazawa H. Long-term outcomes for 32 cases of Wilson's disease after living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87:261–267. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181919984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gow P.J., Smallwood R.A., Angus P.W., Smith A.L., Wall A.J., Sewell R.B. Diagnosis of Wilson's disease: an experience over three decades. Gut. 2000;46:415–419. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellary S.V., Van Thiel D.H. Wilson's disease: a diagnosis made in two individuals greater than 40 years of age. J Okla State Med Assoc. 1993;86:441–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerber A., Sarrazin C., Allers C., Markus B., Engels K., Caspary W. [44-year-old patient with fulminant liver failure] Internist (Berl) 2003;44:1301–1307. doi: 10.1007/s00108-003-1016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amano T., Matsubara T., Nishida T., Shimakoshi H., Shimoda A., Sugimoto A. Clinically diagnosed late-onset fulminant Wilson's disease without cirrhosis: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:290–296. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i2.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danks D.M., Metz G., Sewell R., Prewett E.J. Wilson's disease in adults with cirrhosis but no neurological abnormalities. BMJ. 1990;301:331–332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6747.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newsome P.N., Cramb R., Davison S.M., Dillon J.F., Foulerton M., Godfrey E.M. Guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests. Gut. 2018;67:6–19. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.