Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common disorder in the elderly. OA influences the daily life of patients and has become a worldwide health problem. It is still unclear whether the pathogenesis mechanism is different between males and females. This study investigated the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and explored the different signaling pathways of OA between males and females.

Material/Methods

Data sets of GSE55457, GSE55584, and GSE12021 were retrieved from Gene Expression Omnibus to conduct DEGs analysis. Enrichment analysis of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway and Gene Ontology term was performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) bioinformatics tool. The protein interaction network was constructed in Cytoscape 3.7.2. qRT-PCR was then performed to validate the expression of hub genes in OA patients and healthy people.

Results

In total, 4 co-upregulated and 10 co-downregulated genes were identified. We found that enriched pathways were different between males and females. BCL2L1, EEF1A1, EEF2, HNRNPD, and PABPN1 were considered as hub genes in OA pathogenesis in males, while EEF2, EEF1A1, RPL37A, FN1 were considered as hub genes in OA pathogenesis in females. Consistent with the bioinformatics analysis, the qRT-PCR analysis also showed that the gene expression of BCL2L1, HNRNPD, and PABPN1 was significantly lower in male OA patients. In contrast, EEF2, EEF1A1, and RPL37A were significantly lower in female OA patients.

Conclusions

The DEGs identified may be involved in different OA disease progression mechanisms between males and females, and they are considered as treatment targets or prognosis markers for males and females. The pathogenesis mechanism is sex-dependent.

MeSH Keywords: Diagnosis, Orthopedics, Osteoarthritis

Background

The most common manifestation of joint degeneration is osteoarthritis (OA) [1,2]. Pain is the primary symptom of osteoarthritis, and limited joint mobility is seen in some severe cases [3]. OA can cause not only pain but also disability, which is estimated to affect about 7–19% of adults [3]. OA, thus, has become a severe social health problem seriously affecting patients’ daily lives [4,5]. Currently, no drugs can completely cure osteoarthritis. Joint replacement is often given to patients with end-stage OA. The pathogenesis of osteoarthritis has not been well elucidated. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of OA pathogenesis is essential to improve OA treatment strategies.

Loss of cartilage and chondrocyte senescence are 2 significant features of OA [6]. Direct or indirect stress and friction damage to articular cartilage and subchondral bone may be the main inducers of osteoarthritis. It is reported that direct stress can activate articular chondrocytes, causing the secretion of proteases and inflammatory cytokines, subsequently leading to the degradation of collagen in cartilage and surrounding tissues and increased levels of inflammatory mediators [7]. Ligaments become loosened, and nerve reflexion is slowed with age, resulting in joint instability and cartilage damage; these developments lead to pathological changes of osteoarthritis such as chondrocyte activation and increased secretion of proteases and inflammatory cytokines [6]. However, it is unclear whether the OA pathogenesis mechanism is sex-dependent. Bioinformatics analysis technology allows a comprehensive analysis by organizing and integrating data, in which the main research objective is genetic sequencing of data. It has been successfully applied in research on many diseases and has achieved some promising results [8,9]. Bioinformatics analysis also has provided some ideas and evidence regarding the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoarthritis [10].

In the present study, we hypothesized that OA pathogenesis is sex-dependent, and the objective was to compare sex-dependent DEGs between osteoarthritis patients and healthy subjects using bioinformatics tools. The hub genes of DEGs were identified through protein interaction analysis. qRT-PCR was performed to validate the distinct DEGs identified between males and females.

Material and Methods

Microarray data search and election

RNA sequencing data comparing OA patients and healthy subjects were searched from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database [11]. The sequencing results supported by the same platform were downloaded and analyzed.

Identification of DEGs and co-upregulated genes and co-downregulated genes in males and females

Morpheus (Morpheus, https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus) was used to analyze DEGs. Morpheus is an online versatile matrix visualization and analysis software that can analyze the re-organized sequencing data. The heatmap was obtained with Morpheus. Signal-to-noise ratios >2 or <−2 were defined as DEGs. Venny 2.1.0 (http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html) was used to identify the common DEGs in males and females.

Analysis of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment

Analyses of the KEGG pathway and GO term enrichment of DEGs were performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) Bioinformatics Resources to interpret biological processes of DEGs between males and females [12,13].

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis

DEGs of males and females were imported into the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING, www.string-db.org) to establish a PPI network. A combined score >0.5 was defined as identification. The PPI network was imported into Cytoscape software 3.7.2 for protein interaction analysis. With the plugin software Centiscape 2.2, the gene lists of the top 20 ranked in Degree, Betweenness, Closeness, Stress, Radiality, Eccentricity, and EigenVector were obtained. Genes that appeared on every list were considered hub genes.

Synovial fluid collection

From July 2016 to August 2018, synovial fluid samples from non-OA patients (undergoing amputation due to severe trauma) and OA patients in Shanghai Tongji Hospital (6 male non-OA, 6 male OA, 6 female non-OA, and 6 female OA patients) were collected to determine mRNA levels. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Committees of Clinical Ethics of Tongji Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine. Each participant signed the informed consent documents.

qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from synovial fluids samples was isolated with TRIzol. The protocol for cDNA synthesis was reverse transcription at 42°C for 75 min and at 98°C for 5 min. The qPCR protocol was 1. 95°C for 30 s, 40 cycles at 95˚C for 5 s, and 60°C for 30 s. The relative expression level was determined as targeting genes divided by GAPDH. Relative miRNA expression was generated with 2−ΔΔCq method. Primers used in this study are shown in Table 1. All experiments were performed independently in triplicate.

Table 1.

The information of the primers’ sequencing.

| hsa-BCL2L1 – Forward | GAGCTGGTGGTTGACTTTCTC |

| hsa-BCL2L1 – Reverse | TCCATCTCCGATTCAGTCCCT |

| hsa-HNRNPD – Forward | GCGTGGGTTCTGCTTTATTACC |

| hsa-HNRNPD – Reverse | TTGCTGATATTGTTCCTTCGACA |

| hsa-PABPN1 – Forward | GCTGGAAGCTATCAAAGCTCG |

| hsa-PABPN1 – Reverse | CCTGGAGGTGGACTCATATTCA |

| hsa-EEF2 – Forward | AACTTCACGGTAGACCAGATCC |

| hsa-EEF2 – Reverse | TCGTCCTTCCGGGTATCAGTG |

| hsa-EEF1A1 – Forward | TGTCGTCATTGGACACGTAGA |

| hsa-EEF1A1 – Reverse | ACGCTCAGCTTTCAGTTTATCC |

| hsa-RPL37A – Forward | CCAAACGTACCAAGAAAGTCGG |

| hsa-RPL37A – Reverse | GCGTGCTGGCTGATTTCAA |

| hsa-GAPDH – Forward | CCGTTGAATTTGCCGTGA |

| hsa-GAPDH – Reverse | TGATGACCCTTTTGGCTCCC |

Statistical analysis

GraphPad 8.0 was used to perform statistical analysis. The results are presented as mean±standard deviation (mean±SD). The t test was performed to compare expression levels. P<0.05 was regarded as statistical significance. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Results

Identification of DEGs

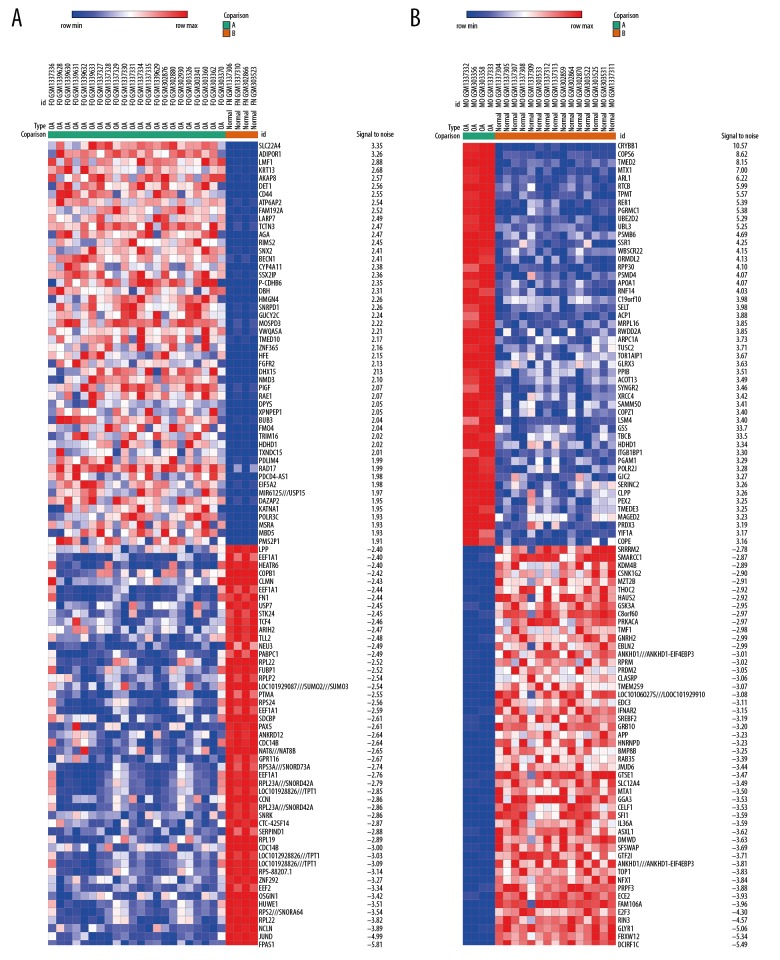

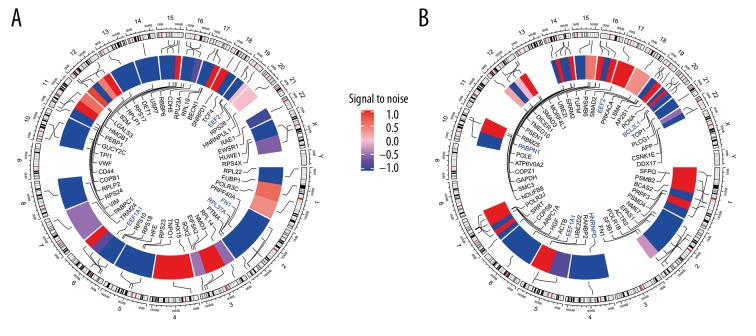

Datasets of GSE55457, GSE55584, and GSE12021 supported by platform GPL96 were obtained from GEO. There were 22 osteoarthritis cases and 4 normal cases in the female group and 4 OA cases and 15 normal cases in the male group after screening and organizing. We identified 128 downregulated DEGs and 54 upregulated DEGs in females, and 336 downregulated DEGs and 220 upregulated DEGs were identified in males. The top 50 upregulated and downregulated genes of females and males are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Heat map of the top 100 DEGs of GSE55457, GSE55584, and GSE12021. Red represents upregulation and blue represents downregulation. (A) Females. (B) Males.

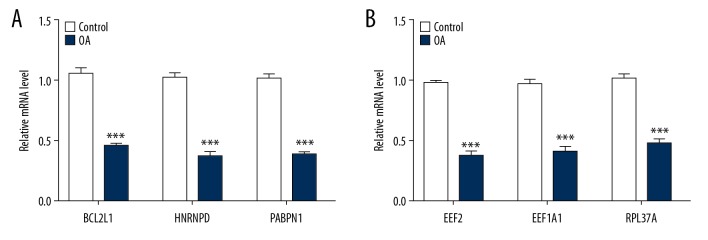

Identification of common DEGs in males and females

The DEGs lists of males and females were imported into the Venn Diagram online tool. The intersection of upregulated DEGs in OA of females and males was obtained as co-upregulated DEGs (SNX2, HMGN4, TMED10, HDHD1). The intersection of downregulated DEGs in OA of female and male was obtained as co-downregulated DEGs (TNPO1, KRTAP5-8, FN1, RBBP6, TOB2, CAPN2, LPP, EEF1A1, EEF2, EPAS1) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Co-upregulated and downregulated DEGs were calculated by Venn diagram. The intersection of purple (upregulated DEGs in females) and green (upregulated DEGs in males) represents co-upregulated DEGs. The intersection of yellow (downregulated DEGs in females) and pink (downregulated DEGs in males) represents co-downregulated DEGs.

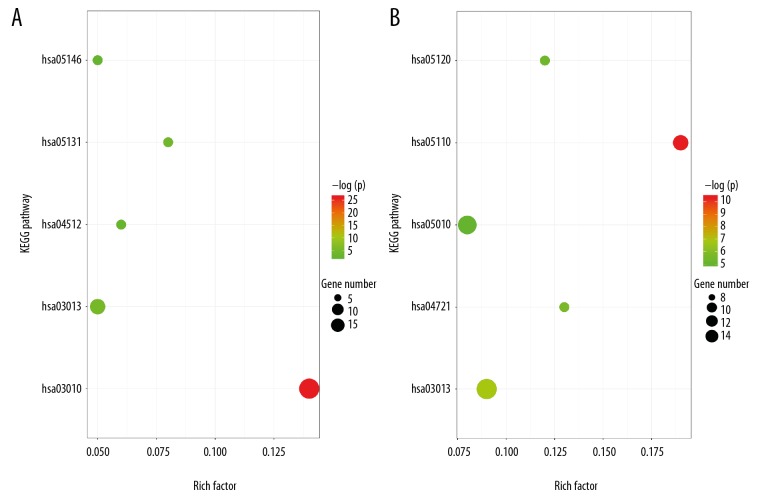

Enrichment analysis of KEGG pathway and GO terms

Analysis of GO term enrichment showed that female-specific DEGs were significantly enriched in protein targeting to ER, cotranslational protein targeting to membrane, and SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane of biological precess; in structural constituent of ribosome, RNA binding, and Poly(A) RNA binding of molecular functions; and in cytosolic ribosome, ribosomal subunit, adherens junction of cellular component (Table 2). The male-specific DEGs were significantly enriched in response to endogenous stimulus, cellular response to endogenous stimulus, gene expression of biological process; and in organic cyclic compound binding, Poly(A) RNA binding, RNA binding of molecular functions; in nucleoplasm, cytosol, nucleoplasm part of cellular component (Table 3). The 5 KEGG pathways with smallest p values in females were ribosome pathway, RNA transport pathway, shigellosis pathway, ECM-receptor interaction pathway, and amoebiasis pathway. The 5 KEGG pathways with smallest p values in males were Alzheimer’s disease pathway, vibrio cholerae infection pathway, RNA transport pathway, epithelial cell signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection, and synaptic vesicle cycle pathway (Table 4, Figure 3).

Table 2.

GO analysis of DEGs of female in biological process, molecular function and cellular component.

| Term | Name | Count | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A, Biological Processes | |||

| GO: 0006614 | SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 19 | 7.2E-17 |

| GO: 0006613 | Cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 19 | 2.7E-16 |

| GO: 0045047 | Protein targeting to ER | 19 | 3.2E-16 |

| B, Molecular Functions | |||

| GO: 0044822 | Poly(A) RNA binding | 48 | 8.2E-13 |

| GO: 0003723 | RNA binding | 56 | 5.0E-12 |

| GO: 0003735 | Structural constituent of ribosome | 19 | 3.4E-10 |

| C, Cellular component | |||

| GO: 0022626 | Cytosolic ribosome | 20 | 2.4E-15 |

| GO: 0044391 | Ribosomal subunit | 20 | 5.0E-12 |

| GO: 0005912 | Adherens junction | 35 | 1.8E-11 |

Table 3.

GO analysis of DEGs of male in biological process, molecular function and cellular component.

| Term | Name | Count | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A, Biological Processes | |||

| GO: 0009719 | Response to endogenous stimulus | 82 | 5.1E-8 |

| GO: 0071495 | Cellular response to endogenous stimulus | 68 | 5.1E-8 |

| GO: 0010467 | Gene expression | 207 | 6.5E-8 |

| B, Molecular Functions | |||

| GO: 0003723 | RNA binding | 79 | 8.5E-6 |

| GO: 0044822 | Poly(A) RNA binding | 62 | 9.1E-6 |

| GO: 0097159 | Organic cyclic compound binding | 219 | 1.6E-5 |

| C, Cellular component | |||

| GO: 0005654 | Nucleoplasm | 150 | 6.3E-11 |

| GO: 0005829 | Cytosol | 152 | 1.5E-7 |

| GO: 0044451 | Nucleoplasm part | 49 | 6.4E-7 |

Table 4.

KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs in females and males. Top 5 terms were selected according to P-value.

| Term | Count | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | ||||

| hsa03010 | Ribosome | 19 | 4.0E-12 | RPL19, RPL14, RPL27A, RPLP2, RPL23A, RPS4X, RPS2, RPS18, RPS28, RPS17, RPS3A, RPL13A, RPL22, RPLP1, RPL3, RPL37A, RPS10, RPS23, RPS24 |

| hsa03013 | RNA transport | 9 | 6.9E-3 | SUMO3, SUMO2, EEF1A1, RAE1, NUP50, LOC101929087, PABPC1, FXR2, NMD3 |

| hsa05131 | Shigellosis | 5 | 2.0E-2 | ACTB, ACTG1, CTTN, CD44, RELA |

| hsa04512 | ECM-receptor interaction | 5 | 5.3E-2 | VWF, LAMA3, COL4A1, CD44, FN1 |

| hsa05146 | Amoebiasis | 5 | 9.4E-2 | LAMA3, COL4A1, RELA, GNAS, FN1 |

| Male | ||||

| hsa05110 | Vibrio cholerae infection | 10 | 3.1E-5 | ACTB, ATP6V1C1, ACTG1, PLCG1, PRKACA, ATP6V1G1, ATP6V0D1, ATP6V1D, ATP6V0A2, ATP6V0B |

| hsa03013 | RNA transport | 15 | 1.0E-3 | EEF1A1, RGPD5, RGPD8, RGPD4, DDX39B, RGPD3, NXF2B, NXF2, UBE2I, NXF1, RPP30, POP4, RANBP2, THOC2, THOC1 |

| hsa04712 | Synaptic vesicle cycle | 8 | 3.6E-3 | ATP6V1C1, CPLX2, AP2S1, ATP6V1G1, ATP6V0D1, ATP6V1D, ATP6V0A2, ATP6V0B |

| hsa05120 | Epithelial cell signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection | 8 | 5.2E-2 | ATP6V1C1, PLCG1, ATP6V1G1, IKBKB, ATP6V0D1, ATP6V1D, ATP6V0A2, ATP6V0B |

| hsa05010 | Alzheimer’s disease | 13 | 6.9E-3 | APP, NDUFB6, ATP2A2, PSEN1, NDUFB8, NDUFV2, PPP3R1, FADD, ATP5G1, CAPN2, NDUFA1, APBB1, GAPDH |

KEGG – Kyoto Encyclopedia Genes and Genomes.

Figure 3.

(A) Enrichment analysis results of DEGs in females. (B) Enrichment analysis results of DEGs in males.

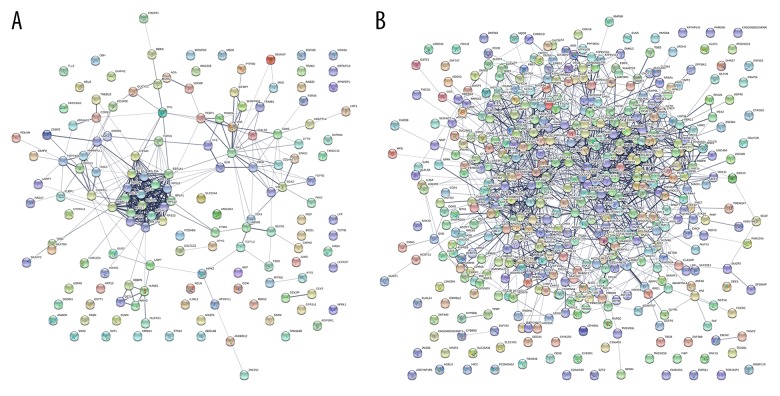

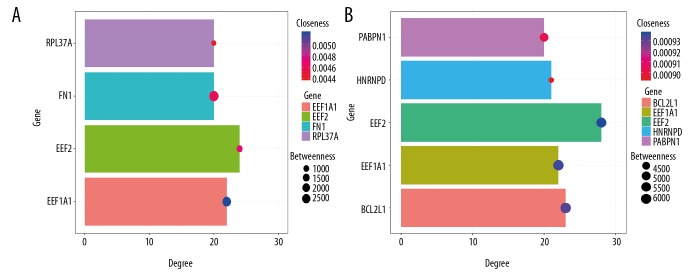

Construction of PPI network and identification of hub genes

The PPI network was constructed by STRING (Figure 4). The network file was imported into Cytoscape 3.7.2. The genes were ranked by Degree, Betweenness, Closeness, Stress, Radiality, Eccentricity, and EigenVector. EEF2, EEF1A1, RPL37A, and FN1 were considered as hub genes in females. BCL2L1, EEF1A1, EEF2, HNRNPD, and PABPN1 were considered as hub genes in males. The degree, betweenness, and closeness information of hub genes is listed in Figure 5. The top 50 genes of degree in the PPI network are shown in Figure 6 with information on gene position and signal-to-noise ratios.

Figure 4.

PPI network of DEGs in females and males constructed by STRING. (A) Females. (B) Males.

Figure 5.

Information on hub genes in females and males. The length of the column represents the value of degree, the size of the bubble represents the value of betweenness, and the color of the bubble represents the value of closeness. (A) Females. (B) Males. Degree represents the association degree of one node and all the other nodes in the network. Closeness is the close degree of a node and other nodes in the network. Betweenness is the number of times that a node acts as the shortest bridge between the other 2 nodes.

Figure 6.

Top 50 genes of degree in the PPI network of females and males. The color of the sectors represents the signal-to-noise value. The labels of hub genes are in blue. (A) Females. (B) Males.

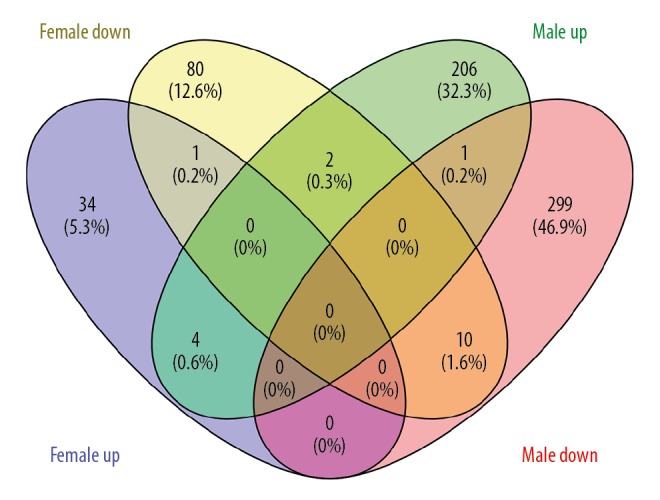

Validation of the hub genes in OA patients

Six male non-OA patients, 6 male OA patients, 6 female non-OA patients, and 6 female OA patients were collected for determination of mRNA levels. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 5. It was found that the expression of BCL2L1, HNRNPD, and PABPN1 in OA patients was lower than in healthy people in males, and the expression of EEF2, EEF1A1, and RPL37A in OA patients was lower than in healthy people in females (p<0.001) (Figure 7).

Table 5.

Characteristics of the included cases.

| Number | Sex | Age | OA (Yes/No) | Ethnic | BMI, kg/m2 | Concomitant with severe trauma (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 47 | No | Han | 28 | Yes |

| 2 | Male | 54 | No | Han | 24 | Yes |

| 3 | Male | 57 | No | Han | 27 | Yes |

| 4 | Male | 46 | No | Han | 26 | Yes |

| 5 | Male | 52 | No | Han | 32 | Yes |

| 6 | Male | 55 | No | Han | 25 | Yes |

| 7 | Male | 56 | Yes | Han | 26 | No |

| 8 | Male | 54 | Yes | Han | 24 | No |

| 9 | Male | 51 | Yes | Han | 31 | No |

| 10 | Male | 59 | Yes | Han | 29 | No |

| 11 | Male | 51 | Yes | Han | 31 | No |

| 12 | Male | 47 | Yes | Han | 27 | No |

| 13 | Female | 49 | No | Han | 27 | Yes |

| 14 | Female | 54 | No | Han | 25 | Yes |

| 15 | Female | 54 | No | Han | 24 | Yes |

| 16 | Female | 46 | No | Han | 26 | Yes |

| 17 | Female | 57 | No | Han | 31 | Yes |

| 18 | Female | 59 | No | Han | 29 | Yes |

| 19 | Female | 56 | Yes | Han | 27 | No |

| 20 | Female | 54 | Yes | Han | 27 | No |

| 21 | Female | 54 | Yes | Han | 31 | No |

| 22 | Female | 59 | Yes | Han | 29 | No |

| 23 | Female | 51 | Yes | Han | 31 | No |

| 24 | Female | 57 | Yes | Han | 27 | No |

OA – osteoarthritis; BMI – body mass index

Figure 7.

Expression of hub genes in men and women. (A) The expression of BCL2L1, HNRNPD, and PABPN1 in OA patients was lower than in normal people in males. (B) The expression of EEF2, EEF1A1, and RPL37A in OA patients was lower than in normal people in females. *** p<0.001.

Discussion

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common disorder in the elderly. Pain is the main symptom, and in some severe cases, joint mobility is limited [3]. Osteoarthritis influences the daily life of patients and has become a worldwide health problem, affecting 7–19% of adults [14–18]. It is a major source of pain and disability in the elderly. There are no currently available drugs that can completely cure OA, and it is often hard to avoid joint replacement in patients with end-stage OA. Osteoarthritis is age-related, and the pathological basis is cartilage degeneration [19]. However, the mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis has not been fully elucidated, and it is also unclear whether the pathogenesis mechanism is sex-dependent.

In this study, after data extraction and collation of GSE55457, GSE55584, and GSE12021, we compared 22 females with OA and 4 normal females and 4 males with OA and 15 normal males. In total, 128 downregulated DEGs and 54 upregulated DEGs were identified in females, and 220 upregulated and 336 downregulated DEGs were identified in males. SNX2, HMGN4, TMED10, and HDHD1 were considered as co-upregulated DEGs, and TNPO1, KRTAP5-8, FN1, RBBP6, TOB2, CAPN2, LPP, EEF1A1, EEF2, and EPAS1 were considered as co-downregulated DEGs between males and females. These genes may potentially participate in the onset and progression of osteoarthritis in both males and females. In this study, the 5 KEGG pathways with smallest p values enriched in females were ribosome pathway, RNA transport pathway, shigellosis pathway, ECM-receptor interaction pathway, and amoebiasis pathway. The 5 KEGG pathways with smallest p values enriched in males were vibrio cholerae infection pathway, RNA transport pathway, Alzheimer’s disease pathway, synaptic vesicle cycle pathway, and epithelial cell signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection. The ribosome and RNA transport KEGG pathway have been previously shown to participate in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis [20,21]. Many studies also showed that ECM-receptor interaction is involved in osteoarthritis development [22–35]. However, the association of sex on these pathways involved in OA has not been studied. Interestingly, the ribosome pathway has also been found to play a dominant role in rheumatoid arthritis [36]. Although there are few reports on the relationship between the KEGG pathway in Alzheimer’s disease and osteoarthritis, it was found that osteoarthritis can accelerate and exacerbate Alzheimer’s disease pathology in mice [37]. For the other KEGG pathways DEGs enriched in males, there are few reports regarding their relationship with osteoarthritis. Therefore, it is possible that the results from most of the previous studies might be neutralized or biased as they did not consider sex differences in OA progression. Although the clinical manifestations of osteoarthritis in women and men are similar, our results show that the pathogenesis may not be the same. Further research is necessary to focus on the mechanism based on sex differences.

In the analysis of PPI network construction, EEF2, EEF1A1, RPL37A, and FN1 were identified as hub genes in females, BCL2L1, EEF1A1, EEF2, HNRNPD, and PABPN1 were identified in males, and EEF2 and EEF1A1 were identified as hub genes both in females and males. However, other hub genes are totally different between different males and females. By synovial fluid test, it was found that the expression of BCL2L1, HNRNPD, and PABPN1 in OA patients was lower than in healthy people in males and the expression of EEF2, EEF1A1, RPL37A in OA patients was lower than in healthy people in females (p<0.001). Mi et al. identified RPL37A as the hub gene of osteoarthritis in women, which is consistent with our results [21]. FN1 is an osteoarthritis regulator [38] and BCL2L1 is a prosurvival gene related to OA [39]. From the top 50 genes of the degree in the PPI network of females, HUWE1 and RPS4X are located on chromosome X, while there are no genes on X chromosome in males (Figure 6). RPS4X was also considered as an important gene in osteoarthritis in another study [21]. It appears that osteoarthritis in men and women may have different pathogenesis mechanisms.

There are some limitations of this study. First, the sample size was small, as we included only 22 osteoarthritis patients and 4 normal individuals among females and 4 OA patients and 15 normal individuals among males. Second, we did not perform a subgroup analysis based on the causes of osteoarthritis, so our results might have been affected by confounding factors. However, our bioinformatics analysis results are consistent with qRT-PCR results, indicating that our results are reliable.

Conclusions

We obtained different hub genes of osteoarthritis for females and males by identifying DEGs and performing enrichment analysis for females and males separately. We concluded that the development of osteoarthritis in women and men is different. Our results provide some preliminary data for further mechanism investigation and “precision treatment”.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all the synovial fluid donors from Tongji Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation Committee of China under contract Nos. 81472144 and 31600754

References

- 1.Hoshikawa N, Sakai A, Takai S, et al. Targeting extracellular miR-21-TLR7 signaling provides long-lasting analgesia in osteoarthritis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2019;19:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Si HB, Yang TM, Li L, et al. miR-140 attenuates the progression of early-stage osteoarthritis by retarding chondrocyte senescence. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2019;19:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2005;365:965–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen A, Gupte C, Akhtar K, et al. The global economic cost of osteoarthritis: How the UK compares. Arthritis. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/698709. 698709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connell B, Wragg NM, Wilson SL, et al. The use of PRP injections in the management of knee osteoarthritis. Cell Tissue Res. 2019;376:143–52. doi: 10.1007/s00441-019-02996-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang X, Ni B, Xi Y, et al. Protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR-2) antagonist AZ3451 as a novel therapeutic agent for osteoarthritis. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;2019:11. doi: 10.18632/aging.102586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Xiao J, Bai J, et al. Molecular characterization and clinical relevance of m6A regulators across 33 cancer types. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:137. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schelker M, Feau S, Du J, et al. Estimation of immune cell content in tumour tissue using single-cell RNA-seq data. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2032. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Mi B, Lv H, et al. Shared KEGG pathways of icariin-targeted genes and osteoarthritis. J Cell Biochem. 2018;120:7741–50. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clough E, Barrett T. The gene expression omnibus database. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1418:93–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang dW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA, et al. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang dW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA, et al. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, et al. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105:185–99. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Niu J. Editorial: Shifting gears in osteoarthritis research toward symptomatic osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1797–800. doi: 10.1002/art.39704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezzat AM, Li LC. Occupational physical loading tasks and knee osteoarthritis: A review of the evidence. Physiother Can. 2014;66:91–107. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2012-45BC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neogi T. The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Modawi RN, Brinchmann JE, Karlsen TA. Multi-pathway protective effects of microRNAs on human chondrocytes in an in vitro model of osteoarthritis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2019;17:776–90. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maudens P, Seemayer CA, Thauvin C, et al. Nanocrystal-polymer particles: Extended delivery carriers for osteoarthritis treatment. Small. 2018;14:1703108. doi: 10.1002/smll.201703108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gago-Fuentes R, Fernández-Puente P, Megias D, et al. Proteomic analysis of connexin 43 reveals novel interactors related to osteoarthritis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:1831–45. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.050211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mi B, Liu G, Zhou W, et al. Identification of genes and pathways in the synovia of women with osteoarthritis by bioinformatics analysis. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:4467–73. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.8429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He P, Zhang Z, Liao W, et al. Screening of gene signatures for rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis based on bioinformatics analysis. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:1587–93. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li HZ, Lu HD. Transcriptome analyses identify key genes and potential mechanisms in a rat model of osteoarthritis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018;13:319. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-1019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ntoumou E, Tzetis M, Braoudaki M, et al. Serum microRNA array analysis identifies miR-140-3p, miR-33b-3p and miR-671-3p as potential osteoarthritis biomarkers involved in metabolic processes. Clin Epigenetics. 2017;9:127. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo SM, Wang JX, Li J, et al. Identification of gene expression profiles and key genes in subchondral bone of osteoarthritis using weighted gene coexpression network analysis. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:7687–95. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan Y, Chen J, Yang Y, et al. Genome-wide expression and methylation profiling reveal candidate genes in osteoarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35:983–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu N, Hou J, Wu Y, et al. Identification of key genes in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis based on bioinformatics analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e10997. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui S, Zhang X, Hai S, et al. Molecular mechanisms of osteoarthritis using gene microarrays. Acta Histochem. 2015;117:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fei Q, Lin J, Meng H, et al. Identification of upstream regulators for synovial expression signature genes in osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83:545–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun J, Yan B, Yin W, et al. Identification of genes associated with osteoarthritis by microarray analysis. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5211–16. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ki T, Hashimoto K, Ogasawara M, et al. A whole-genome transcriptome analysis of articular chondrocytes in secondary osteoarthritis of the hip. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0199734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang W, Liu Y, Hao J, et al. Comparative analysis of gene expression profiles of hip articular cartilage between non-traumatic necrosis and osteoarthritis. Gene. 2016;591:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu HY, Yang M, Guo J, et al. Identification of the biomarkers and pathological process of osteoarthritis: Weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Front Physiol. 2019;10:275. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo H, Yao L, Zhang Y, et al. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics analysis reveals chondroprotective effects of astragaloside IV in interleukin-1β-induced SW1353 chondrocyte-like cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;91:796–802. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.04.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu P, Sun F, Ran J, et al. Identify CRNDE and LINC00152 as the key lncRNAs in age-related degeneration of articular cartilage through comprehensive and integrative analysis. Peer J. 2019;7:e7024. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashi J, Kihara M, Kato H, et al. A proteomic profile of synoviocyte lesions microdissected from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded synovial tissues of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Proteomics. 2015;12:20. doi: 10.1186/s12014-015-9091-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kyrkanides S, Tallents RH, Miller JN, et al. Osteoarthritis accelerates and exacerbates Alzheimer’s disease pathology in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:112. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang JC, Sebastian A, Murugesh DK, et al. Global molecular changes in a tibial compression induced ACL rupture model of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:474–85. doi: 10.1002/jor.23263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wajid N, Mehmood A, Bhatti FU, et al. Lovastatin protects chondrocytes derived from Wharton’s jelly of human cord against hydrogen-peroxide-induced in vitro injury. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;351:433–43. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1540-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]