Abstract

Aims

Vancomycin dosing and monitoring recommendations are poorly adhered to in many institutions internationally, with concerns of treatment failure and propelling antibiotic resistance. The primary aim of this study was to audit the rate of adherence to American guidelines, with particular interest in loading dose administration. The secondary aims were (i) to determine whether or not guideline adherence results in therapeutic concentrations across body mass index (BMI) groups and (ii) to determine whether or not this was in turn associated with morbidity and hospital mortality.

Method

Data were collected in a single tertiary hospital on all patients who had two or more serum vancomycin concentrations measured.

Result

In total, 107 patients met the inclusion criteria. Overall, 38.3% of patients were commenced on guideline adherent vancomycin doses, and 28.3% of overweight patients received an adherent first dose compared to 51.1% of non‐overweight people (difference 23%, 95% CI 4% to 41%, P = 0.024). Overweight patients were more frequently underdosed compared to non‐overweight patients (P = 0.039). The frequency and proportion of underdosing increased with BMI. Overweight patients spent a smaller fraction of their course within the therapeutic range, although the difference was not statistically significant (difference 7.7%; 95% CI 4% to 19.4%; P = 0.195). The overweight group had longer hospital length of stay (LOS), higher mortality and more treatment failures.

Conclusion

Adherence to guideline‐based prescription is poor, particularly in overweight patients. Patients who are initially underdosed have fewer therapeutic vancomycin days, regardless of BMI. Overweight patients have increased hospital LOS, hospital mortality and treatment failure.

Keywords: guideline‐based dosing, obesity, trough concentration, vancomycin

What is already known about this subject

Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus remains a prevalent organism, and vancomycin remains the agent of choice.

Inadequate exposure contributes to antibiotic resistance.

Current guidelines recommend vancomycin dosing based on total weight adjusted according to trough concentration, a surrogate measure of the gold standard AUC0‐24/MICBMD

Vancomycin treatment failure is correlated with subtherapeutic trough concentrations of <10 mg/L

What this study adds

Adherence to current weight‐based guidelines is poor. Doses were more commonly under‐dosed, particularly in patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2. We observed that the higher the BMI, the more frequent the underdosing and the higher the degree of underdosing.

There was an association between overweight grouped patients and longer hospital length of stay, higher mortality rates and ICU admissions

Patients who received adherent vancomycin doses contributed to less subtherapeutic trough concentrations during treatment duration, suggesting that current weight‐based guidelines are adequate in maintaining therapeutic trough concentrations, regardless of BMI.

In patients who were adherent to guideline‐based dosing or overdosed, there was an association between overweight patients and a higher number of therapeutic vancomycin days compared to the non‐overweight group.

1. INTRODUCTION

There has been a steady increase in the number of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections since the 1990s. In Australia, 18.8% of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (SAB) are methicillin‐resistant, with a higher all‐cause mortality of 23.4% compared to methicillin‐sensitive SAB (14.4%).1 Therapeutic concentrations of vancomycin are required for safe and effective therapy and to minimize the emergence of resistant microbes.2 As a consequence, it is critical to examine and improve the dosing and monitoring of this agent.

In Australia, vancomycin dosing is based on internationally accredited guidelines, specifically those in the consensus statements from the American Society of Health System Pharmacists, the Infectious Disease Society of America and the Society of Infectious Disease Pharmacists (2009), from here on referred to as the American Guideline or the Guideline.3 This Guideline recommends intermittent dosing calculated according to actual body weight for all body mass indices combined with the addition of a loading dose for patients who are critically ill.3

This approach is supported by modelling and simulation3 but validation of this modelling work in the obese hospitalized population has not previously been studied. Dosing and monitoring guidelines continue to be poorly adhered to, propelling antibiotic resistance and delay in clinical recovery.4, 5, 6

In the face of increasing global prevalence of obesity7, 8 it is essential to determine whether guidelines are being adhered to and if so whether or not this will result in therapeutic concentrations.9

1.1. Aim

The primary aim of this study was to describe vancomycin administration practices in a single Australian tertiary academic centre utilizing internationally accredited American dosing guidelines. Loading dose administration, as a surrogate for rapid therapeutic concentration attainment, was of particular interest. The secondary aims were to determine whether there were differences in achieved concentrations between non‐overweight and overweight groups using the current loading dose guideline, and to describe associated changes in morbidity and hospital mortality.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Hunter New England Local Health District research ethics committee (AU201707–05).

2.1. Patients

This was a non‐interventional retrospective study in a single centre. All patients at least 18 years of age admitted to the John Hunter Hospital (New South Wales, Australia) between September 2016 and March 2017 who had two or more vancomycin concentration measurements taken were identified from the hospital laboratory's computerized information system (Auslab®). Data from patients whose files were not accessible via electronic medical records, those who received continuous vancomycin infusions and those who received any renal replacement therapy during their treatment with vancomycin were excluded.

2.2. Data collection

Data were abstracted from the area network digitalized medical record (DMR) and pathology information system (AusLab®). Extracted data included patient demographics (age, sex), anthropometric data (height, weight, calculated BMI), laboratory information (urea, creatinine, specimen type, culture), indications for vancomycin administration, dosing and administration information, as well as encounter data (intensive care unit [ICU] admission, hospital admission and discharge dates, mortality). Indications for vancomycin therapy were confirmed from written notes by the treating team, and patients with contaminant cultures were excluded from the study. Collected data were independently verified by two independent members; discrepancies were reviewed and consensus achieved to maintain the accuracy of data collection.

2.3. Definitions

Patient were divided into two groups according to the BMI classification outlined by the World Health Organization (Table 1). For the purpose of this study, patients with BMI ≥25 kg/m2 were classified as overweigh, and those with BMI <25 kg/m2 were classified as non‐overweight.

Table 1.

World Health Organization BMI classification8

| Class | BMI range (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| Normal (N) | ≥18.5 and < 25 |

| Overweight (O) | ≥25 and < 30 |

| Obese class I (O1) | ≥30 and < 35 |

| Obese class II (O2) | ≥35 and < 40 |

| Obese class III (O3) | ≥40 and < 50 |

| Morbidly obese (O4) | ≥50 |

Guideline Adherent Dosing (including a loading dose in critically ill patients)

Guideline‐adherent dosing was determined against the Hunter New England Local Health District Vancomycin Drug Prescribing Guideline, which adheres to the American Guideline. According to the Guideline vancomycin should initially be prescribed at 15‐20 mg/kg of actual body weight (ABW) with a dose interval determined by renal function, but typically 12 hourly. The dose is modified according the vancomycin plasma concentration measured 30 minutes before the fourth dose is scheduled. When the concentration is not therapeutic (see below) the regular dose is adjusted proportionately and the process is repeated. Once a therapeutic concentration is attained, the Guideline only requires weekly vancomycin concentration measurement as a minimum. The Guideline advises that the first vancomycin dose in critically ill patients should be a loading dose of 25‐30 mg/kg of ABW instead of 15‐20 mg/kg. We classified patients as critical if they were admitted to the ICU or if Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia had been identified at the time of vancomycin prescription.

Patients were said to be underdosed if they were prescribed doses lower than the weight‐based doses described above and overdosed if they were prescribed doses higher than these. We allowed for a difference of ±250 mg from the calculated dose for the practicality of dose administration, as supported by the revised American Guideline.3

Therapeutic vancomycin concentration

Therapeutic trough concentration was defined as being 15‐20 mg/L for critically ill and 10‐20 mg/L for non‐critically ill patients. That is, any trough concentration > 20 mg/L was classified as supratherapeutic and a concentration < 15 mg/L in a critically ill patient or < 10 mg/L in a non‐critically ill patient was classified as subtherapeutic.

Vancomycin trough concentration

Following Morrison et al.10 and the American Guideline3 we defined trough concentration as one taken within 2 hours of a subsequent vancomycin dose and after at least 36 hours on the same dose (i.e. at “steady state”).

Acute kidney impairment

Acute kidney impairment during vancomycin therapy was defined according to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes definition, defined as either an increase in serum creatinine by ≥26.5 µm/L within 48 hours or increasing in serum creatinine to 1.5 times baseline.11

2.4. Data analysis

Categorical data were compared using Fisher's exact test. Continuous data were assessed for normality based on histogram and the Shapiro‐Wilk test, where Student's t test was used for normal numerical data and the Wilcoxon‐rank sum test was applied for non‐normal data. For the purpose of analysis any subtherapeutic vancomycin concentration was assumed to have persisted from the time of last measurement, or the first dose of vancomycin if there were no prior measurements. Since 21 of 107 patients never achieved a therapeutic vancomycin concentration, a Kaplan‐Meier curve was generated and a log‐rank test performed to compare times to reach therapeutic concentration. Two‐sided P values were reported in all cases. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population

From September 2017 to March 2018, a total of 488 adult patients received vancomycin doses at John Hunter Hospital. Out of the 488 patients, 107 patients had two or more vancomycin trough concentration taken. As shown in Table 2, 63.0% of patients were male, with a mean age of 56.4 years (range 16‐91) and mean BMI of 29.0 kg/m2 for both male and female sex.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| Total (n = 107) | Non‐overweight (n = 47) | Overweight (n = 60) | Fisher or t test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Sex: male, n (%) | 68 (63.0) | 33 (70.2) | 35 (57.3) | P = 0.23a |

| Age: range, mean, s.d. | 16‐91, 56.4 (18.0) | 16‐91, 52.8 (20.5) | 18‐90, 59.2 (15.6) | P = 0.069b |

| Morbidity data | ||||

| Specimen type: n (%) | P = 0.36a | |||

| • Blood | 32 (29.1) | 15 (31.9) | 17 (28.9) | |

| • Tissue sample | 21 (19.6) | 11 (23.4) | 10 (16.4) | |

| • Wound swab | 28(26) | 8 (17.0) | 20 (32.8) | |

| • Nasal/oral/axillary | 5 (4.7) | 3 (6.4) | 2 (3.3) | |

| • Sputum | 4 (3.7) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (3.3) | |

| • Aspirate | 8 (7.5) | 5 (10.6) | 3 (4.1) | |

| • Urine | 1 (0.9) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | |

| • Device | 8 (7.5) | 2 (4.3) | 6 (9.8) | |

| • Nil | 0 | |||

| Indication for vancomycin: n, (%) | P = 0.54a | |||

| • MRSA | 35 (32.7) | 18 (38.3) | 17 (28.3) | |

| • CoNS | 19 (17.8) | 7 (14.9) | 12 (20) | |

| • Hypersensitivity to penicillin | 5 (4.7) | 1 (2.1) | 4 (6.7) | |

| • Empirical | 48 (44.9) | 21 (44) | 27 (45) | |

Abbreviation: MRSA, methicillin‐resistant Staphyloccocus aureus; CoNS, coagulase‐negative staphylococci.

Fisher's exact.

Unpaired Student's t test.

The range of BMI was 14.5‐54.9 kg/m2. Within the study population, 60 patients (56.1%) were overweight with a mean BMI of 34.6 kg/m2. When subclassified according to their WHO category, O, O1, O2, O3 and O4 comprised 17.8%, 16.8%, 10.3%, 8.4% and 2.8%, respectively. Thirty‐five patients (32.7%) received vancomycin to treat MRSA and 19 (17.8%) patients had CoNS infection, with a low suspicion of contaminant cultures (Table 2). Positive microbiological results were obtained largely from blood cultures (29.1%), followed by wound swabs (26.0%) and tissue samples (19.6%). Figure S1 indicates the hospital team patients were admitted under.

3.2. Vancomycin dosing and adherence to the Guideline

-

1

Initial dose

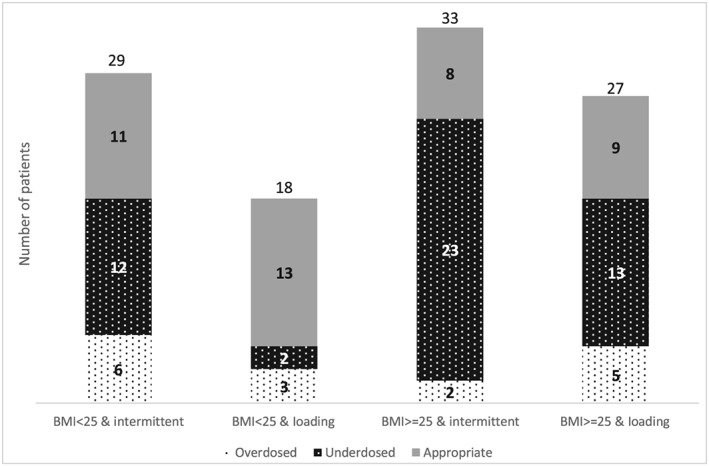

Figure 1 shows a graphical representation of overweight and non‐overweight patients and their initial dose adherence according to the Guideline. Overall, 38.3% of patients were commenced on Guideline‐adherent vancomycin doses. Comparison between BMI groups showed that 28.3% of overweight patients received an appropriate Guideline‐based dose, vs 51.1% of non‐overweight patients (difference 23%, 95% CI 4% to 41%, P = 0.024) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the number of patients who received vancomycin therapy and their dose adherence

Amongst patients who received a Guideline non‐adherent first dose, 83.7% of overweight patients were underdosed and 16.3% of overweight patients were overdosed, compared to 58.3% and 41.2% of non‐overweight patients who were under and overdosed, respectively (P = 0.039). It was more common to be underdosed based on the patients' creatinine clearance and weight (80%) rather than their requirement for a loading dose (20%).

Initial dosing was largely confined to a very small number of patients (Table 3). Of the 62 patients who did not receive a loading dose, 55(89%) received either 1000 or 1500 mg every 12 hours with a further three patients (4.8%) receiving 750 mg every 12 hours (Table 3a). Of the 45 patients who received loading doses, their doses were prescribed as 1500, 2000, 1000, or 2500 mg, which accounts for 36 (80%) of the prescribed dose (Table 3b.)

Table 3.

Three most common doses used for initial dose

| Dosage regimen | n (%) |

|---|---|

| A | |

| 1000 mg q12 hourly | 31 (50.0) |

| 1500 mg q12 hourly | 24 (38.7) |

| 750 mg q12 hourly | 3 (4.84) |

| All others | 4 (6.45) |

| Loading dose (mg) | n (%) |

| B | |

| 1500 | 15 (33.3) |

| 2000 | 10 (22.2) |

| 1000 | 7 (15.6) |

| All others | 13 (28.9) |

Note. Only two dosage regimens accounted for almost 90% of the 62 patients not receiving a loading dose (Table 3A). One of three doses accounted for almost three‐quarters of 45 loading doses (Table 3B).

Frequency of underdosing increased with BMI (P = 0.02) (Table S2). When different BMI categories were compared to the degree of underdosing, it showed that the degree of underdosing increased with increasing BMI (mean 0.71 g, 95% CI –0.89 to −0.53). Statistical significance was not produced due small sample size (Table S3).

-

2

Vancomycin trough concentrations and dose adjustment practices

There were a total 551 vancomycin concentrations collected from the study population whilst under observation. Of these, 91 (16.5%) were < 10 mg/L, 327 (59.3%) were between 10 and 20 mg/L, and 133 (24.1%) were > 20 mg/L. Out of the 327 concentrations that were between 10 and 20 mg/L, 198 concentrations belonged to patients who were critically ill, of which 23 concentrations were measured as subtherapeutic (<15 mg/L). Overall, the dose was adjusted in 66 (57.9%) of patients with subtherapeutic concentrations and 73(53.4%) of those with supratherapeutic concentrations.

-

3

Relationship between initial dose and fraction of days spent within the therapeutic range

Of the 1145 vancomycin treatment days in the study population, on average each patient spent 56.3% of their vancomycin course within the therapeutic range (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mean proportion of vancomycin treatment spent within the therapeutic range

| As per guideline | Non‐overweight, BMI > 25 (%) | Overweight, BMI ≥ 25 (%) | Combined (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underdosed | 63.2 | 54.3 | 56.8 |

| Adherent | 57.1 | 48.2 | 53.4 |

| Overdosed | 66.0 | 57.1 | 62.1 |

| Total | 60.6 | 52.9 | 56.3 |

Note. Overweight patients spend 7.7% (95%CI –4.0% to 19%, P = 0.165) less of their treatment time in the therapeutic range.

Twenty‐one of 107 patients never reached therapeutic trough concentrations within their treatment period, which comprised a total of 101 vancomycin days within our study population. Overweight patients spent a smaller fraction of their course within the therapeutic range regardless of whether their initial dosing was classified as underdosing, adherent or overdosing. Non‐overweight patients were therapeutic for an average of 60.6% of their time compared to 52.9% for their overweight counterparts. The difference was not statistically significant (difference 7.7%; 95% CI 4.0% to 19.4%: P = 0.195.)

Figure 2 shows that the times to reach a therapeutic vancomycin concentration were virtually identical in overweight and non‐overweight patients (P = 0.67). Whilst 21 patients (12 non‐overweight and 9 overweight) never reached therapeutic concentration, the graph shows that this was evenly distributed throughout both groups at each time frame. The median time to reach a therapeutic dose was 4 days in non‐overweight patients and 3 days in overweight patients. It took 6 days for 75% of non‐overweight patients to become therapeutic and 7 days for overweight patients.

Figure 2.

Kaplan‐Meier curve representing the proportion of patients in each group who did not reach therapeutic concentrations

3.3. Clinical outcomes

The numbers of patients with proven MRSA and CoNS were similar in the overweight and non‐overweight groups (29 vs 25). Of these patients, 79.3% of those who were in the overweight group received Guideline non‐adherent dosing compared to 48% in the non‐overweight group (P = 0.023). Median length of hospital stay in patients was 27.5 days (interquartile range (IQR) 13.7, 50.2) in the overweight group compared to 18 days (IQR 10, 40) in the non‐overweight group (P = 0.096) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Outcome measured after commencement of vancomycin therapy

| Total (n/107) | BMI < 25 kg/m2 (n/47) | BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (n/60) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission after commencing therapy: n (%) | 18 (16.8) | 7 (14.9) | 11(18.3) | 0.80a |

| LOS in hospital: range, median (IQR) | 3~187, 25 (13, 46) | 3~113, 18 (10, 40) | 3~187, 27.5 (13.7, 50.5) | 0.096b |

| Mortalityc: n (%) | 11 (10.3) | 4 (8.5) | 7 (11.7) | 0.75a |

| Subsequent positive culture: n (%) | 0.46d | |||

| MRSA | 4 (3.7) | 3 (6.4) | 1 (1.7) | 0.65d |

| VRE | 6 (5.6) | 1 (2.1) | 5 (8.3) | 0.23d |

| Not tested | 46 (43.0) | 22 (46.8) | 24 (40) | 0.56d |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; IQR, interquartile range; MRSA, methicillin‐resistant Staphyloccocus aureus; VRE, vancomycin resistant enterococcus.

Unpaired Student's t test.

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Mortality defined as in‐hospital mortality.

Fisher's exact test.

Subsequent MRSA or vancomycin resistant enterococcus (VRE) positive culture post completion of vancomycin treatment was 10.0% in the overweight group compared to 8.5% in the non‐overweight group (P = 0.461). However, 43.0% of the cohort were not cultured post vancomycin treatment (Table 5).

Lastly, there was a strong association between acute kidney injury at the end of vancomycin therapy and patients who received an initial overdose according to the American Guideline. This occurred in 12 of 17 (70.6%) of patients who received an overdose for their first dose, compared to 25 of 90 (27.8%) of those who were not overdosed, with a difference of 42.8% (95%CI 19.3 to 66.4, P = 0.0015).

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first study to directly examine the dosing of vancomycin in overweight patients in routine hospital practice. We examined whether or not the doses received adhered to internationally accepted guidelines and whether this differed between overweight and non‐overweight patients.

Our study found that Guideline adherence was poor, with a little over one‐third of patients initially prescribed Guideline‐adherent dosing despite being in a teaching hospital.

It was apparent that instead of an ABW‐based dose calculation, prescribers simply choose one of two stereotyped dose/interval combinations accounting for almost 90% of all initial regular dosing. Eighty per cent of the incorrect doses were because patients were not dosed according to ABW and 20% because two‐thirds of critically ill patients did not receive a loading dose. The effect of this pattern of prescription was that a disproportionate number of overweight patients received inadequate initial dosing, particularly in more overweight patients. Out of the patients who had vancomycin concentrations that were over or under the Guideline recommended trough level, only about half of patients received a dose adjustment. This resulted in overweight patients having a lower proportion of their treatment with a therapeutic vancomycin concentration than non‐overweight patients. Interestingly, the time to reach a therapeutic concentration was similar in both overweight and non‐overweight patients. However, typically the first concentration measurement was on the second or third day of treatment and even with full Guideline‐adherence dosage adjustment only occurs at the fifth dose, making the observed time to therapeutic concentration quite imprecise. Since proportional dose adjustment should bring most patients into the therapeutic range regardless of initial dosing,12 the similarity of times to therapeutic concentration should not be surprising.

There was a trend to higher ICU admission and mortality amongst overweight patients, but this study was not powered to detect any difference pertaining to either vancomycin concentration or dosage guideline adherence. There was a similar trend to increased length of stay in overweight patients.

This non‐interventional retrospective audit of a clinical population receiving vancomycin for a range of indications has highlighted several new understandings. To the authors’ knowledge there are no other studies that have described the nature of actual vancomycin prescription in these groups.

Our audit reflects current clinical practice for vancomycin in a large tertiary centre in Australia. Whilst internationally validated dosing guidelines for vancomycin are available, we have shown that best practice is not often followed, even in tertiary academic hospitals, despite the presence of multifaceted interventions such as dose calculators, hospital in‐service and availability of clinical pharmacists.13

Our results add to those described in a survey conducted by Chan et al,14 and in addition support the use of a loading dose to attain rapid target therapeutic concentrations. Lack of rapid attainment of adequate exposure is associated with a reduction in the clinical effect of the bactericidal and bacteriostatic activity of vancomycin.15 Indeed, whilst the study was not powered there was a trend towards morbidity if Guideline non‐adherent initial vancomycin dosing was used, regardless of BMI.

It would be interesting to know if other hospitals have similar dosing practices.16, 17

Second, this study adds to our limited understanding of dosing practice in overweight populations, particularly as obesity is a spectrum and is increasingly observed in clinical practice. Though there are no other published studies that have highlighted this association with vancomycin, a study by Roe et al showed that adherence for first dose was as low as 1.2% for certain antibiotics commonly prescribed in the emergency department in the obese population.18

The combination of insufficient initial dosing, especially in overweight patients, and the observation that the median time to a therapeutic concentration was 3‐4 days with the third quartile out to a week regardless of initial dose is a result of insufficient emphasis on initial dosing. This is likely the result of a passive approach to vancomycin therapeutic dosing, with prescribers and clinical pharmacists only acting once a subtherapeutic concentration is reported. Written advice on vancomycin is provided with positive blood cultures but again this is relatively passive. Evidence suggests that the use of insufficient beneficial effect of conventional strategies such as education and dissemination of written materials to medical staff may have contributed to this problem.19 A study by Fernandez et al highlighted the importance of close communication (written vs oral) and involvement of a specialized clinical unit for successful implementation of therapeutic drug monitoring recommendations.20 Thus, a more active approach, with prescription of any therapeutic dose of vancomycin triggering a review by a pharmacist, may help. Similarly, when a positive culture from a sterile site is identified at the laboratory, advice could be given on appropriate vancomycin dosing, including the use of a loading dose.

Given that most patients received one of two regular intermittent dose regimens it is hardly surprising that some patients with lower BMIs were overdosed. This study demonstrates that dose‐related nephrotoxicity was over‐represented in the overdosed group. This dose‐related nephrotoxicity has been described previously21 and further highlights the importance of individualized dose administration.

4.1. Limitations

The retrospective nature of this study meant the classification and analysis of patients relied on the accuracy and depth of documentation by the patients' treating teams. The retrospective nature also meant we were unable to accurately determine when a therapeutic concentration was achieved as the protocol advised waiting until just before the third dose. Additionally, the study was not powered to detect a difference in clinical outcome.

5. CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that prescription of vancomycin according to two or three simplistic dose regimens results in patients spending a lower fraction of their treatment time within the therapeutic range. We demonstrated that overweight patients bore a disproportionate burden of this underdosing. Patients dosed adherent to an accepted guideline spent a higher fraction of their treatment time within the therapeutic range than those who were not dosed adherently. This suggests that focusing on adherence to initial dosing would improve treatment, especially in overweight patients.

Vancomycin is still the mainstay treatment for MRSA and other methicillin‐resistant CoNS. Obesity is growing worldwide and it follows that an increasing number of patients will have inadequate vancomycin concentrations for treatment of serious infections if this practice continues. Increased exposure of these organisms to subtherapeutic concentrations of antibiotics will promote resistance. Adjustment of dosage based on concentrations measured at the time of a third dose will still leave patients with inadequate concentrations during the crucial initial period of sepsis.

A more active approach focusing on adherence to guidelines advising ABW dosing at the initial prescription rather than waiting for the concentration to be reported may potentially improve this.

Further studies should evaluate this strategy as well as evaluating whether this simple weight‐based approach is as effective as more complicated pharmacokinetic modelling, which we did not address in our study.

CONTRIBUTORS

M.K. was the principal author and investigator, and carried out data collection. R.A. carried out data collection. M.L. carried out data analysis and editing. J.H.M. supervised the work.

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare.

Supporting information

Data S1 Pie chart indicating rates of vancomycin use by hospital team within the single centre.

Table S1. Frequency of appropriate and inappropriate dosing according to BMI category (Pearson χ2 = 18.19, p = 0.02)

Table S2. Statistical summary of degree of under‐dosing according to BMI category. Mean value derived by the average of the difference of the calculated first dose and the administered first dose, expressed to 2 significant figures. Out of 50 patients who were underdosed, mean underdosing was −0.71 g (95% CI ‐0.89 to −0.53)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Nil funding or grants to declare.

Koyanagi M, Anning R, Loewenthal M, Martin JH. Vancomycin: Audit of American guideline‐based intermittent dose administration with focus on overweight patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86:958–965. 10.1111/bcp.14205

The authors confirm that the Principal Investigator for this paper is Mari Koyanagi and that she had direct clinical responsibility for patients.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Australian Government: Department of Health , Australian Group on Antimicrobial Resistance Australian Staphylococcus aureus Sepsis Outcome Programme annual report, (2014), Canberra, http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/cda-cdi4002i.htm, accessed August 15, 2018

- 2. Loomba P, Taneja J, Mishra B. Methicillin and vancomycin resistant S. aureus in hospitalized patients. J Glob Infect. 2010;2(3):275‐283. 10.4103/0974-777x.68535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer J, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health‐System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;66(1):82‐98. 10.2146/ajhp080434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davis SL, Scheetz MH, Bosso JA, Goff DA, Rybak MJ. Adherence to the 2009 consensus guidelines for vancomycin dosing and monitoring practices: a cross‐sectional survey of U.S. hospitals. J Human Pharmacol Drug Therapy. 2013;33(12):1256‐1263. 10.1002/phar.1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bauer L, Black D, Lill J. Vancomycin dosing in morbidly obese patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54(8):621‐625. 10.1007/s002280050524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blouin R, Bauer L, Miller D, Record K, Griffen W. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in normal and morbidly obese subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;22(1):180‐180. 10.1128/aac.22.1.180-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Australian Government: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, A picture of overweight and obesity in Australia , (2017), https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/overweight-obesity/a-picture-of-overweight-and-obesity-in-australia/contents/table-of-contents, Accessed September 2, 2018

- 8. World Health Organisation, Obesity and Overweight , (2019), https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight, Accessed September 4, 2018

- 9. Grace E. Altered vancomycin pharmacokinetics in obese and morbidly obese patients: what we have learned over the past 30 years. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(6):1305‐1310. 10.1093/jac/dks066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morrison AP, Melanson SEF, Carty MG, Bates DW, Szumita PM, Tanasijevic MJ. What proportion of vancomycin trough levels are drawn too early?: frequency and impact on clinical actions. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(3):472‐478. 10.1309/AJCPDSYS0DVLKFOH [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kellum JA, Lameire N, Aspelin P, et al. Kidney disease: improving global outcome (KDIGO) clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2(1):1‐38. 10.1038/kisup.2012.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Drew RH, Sakoulas G. Vancomycin: Parenteral dosing, monitoring, and adverse effects in adults, UpToDate, (2019), https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vancomycin-parenteral-dosing-monitoring-and-adverse-effects-in-adults#H1455059606, Accessed June 2019

- 13. Phillips CJ. Sustained improvement in vancomycin dosing and monitoring post‐implementation of guidelines: results of a three‐year follow‐up after a multifaceted intervention in an Australian teaching hospital. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24(2):103‐109. 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.09.010 Epub 2017 Oct 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan JOS. Barriers and facilitators of appropriate vancomycin use: prescribing context is key. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(11):1523‐1529. 10.1007/s00228-018-2525-2 Epub 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mohammedi I, Descloux E, Argaud L, Le Scanff J, Robert D. Loading dose of vancomycin in critically ill patients: 15mg/kg is a better choice than 500mg. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;27(3):259‐262. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Durand C, Bylo M, Howard B, Belliveau P. Vancomycin dosing in obese patients: special considerations and novel dosing strategies. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52(6):580‐590. 10.1177/1060028017750084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hong J, Krop LC, Johns T, Pai MP. Individualised vancomycin dosing in obese patients: a two‐sample measurement approach improves target attainment. Pharmacotherapy: J Human Pharmacol Drug Therapy. 2015;35(5):455‐463. 10.1002/phar.1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roe JL, Fuentes JM, Mullins ME. Underdosing of common antibiotics for obese patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(7):1212‐1214. 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Phillips CJ, Wisdon AJ, McKinnon RA, Woodman RJ, Gordon DL. Interventions targeting the prescribing and monitoring of vancomycin for hospitalised patients: a systematic review with metaanalysis. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;2018(11):2081‐2084. 10.2147/IDR.S176519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fernandez S, Widmer N, Buclin T, Biollaz J, Csajka C. Evaluation of the impact of a therapeutic drug monitoring program in a Swiss University hospital. Int J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;32(2):283‐284. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lodise TP, Lomaestro B, Graves J, Drusano GL. Larger vancomycin doses (at least four grams per day) are associated with an increased incidence of nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(4):1330‐1336. 10.1128/AAC.01602-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Pie chart indicating rates of vancomycin use by hospital team within the single centre.

Table S1. Frequency of appropriate and inappropriate dosing according to BMI category (Pearson χ2 = 18.19, p = 0.02)

Table S2. Statistical summary of degree of under‐dosing according to BMI category. Mean value derived by the average of the difference of the calculated first dose and the administered first dose, expressed to 2 significant figures. Out of 50 patients who were underdosed, mean underdosing was −0.71 g (95% CI ‐0.89 to −0.53)

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.