Abstract

Purpose of Review

To review literature on progress towards UNAIDS 90–90-90 targets for HIV prevention and treatment among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China.

Recent findings

China has made progress towards UNAIDS 90–90-90 targets among MSM. However, socio-structural barriers, including HIV-related stigma and homophobia, persist at each stage of the HIV care continuum, leading to substantial levels of attrition and high risk of forward HIV transmission. Moreover, access to key prevention tools, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis, is still limited. Multilevel interventions, many using digital intervention, have been shown effective in pragmatic randomized controlled trials in China.

Summary

Multilevel interventions incorporating digital health have led to significant improvement in engagement of Chinese MSM in the HIV care continuum. However, interventions that address socio-structural determinants, including HIV-related stigma and discrimination, towards Chinese MSM are needed.

Keywords: HIV, MSM, China, Review, Treatment, Prevention

Introduction

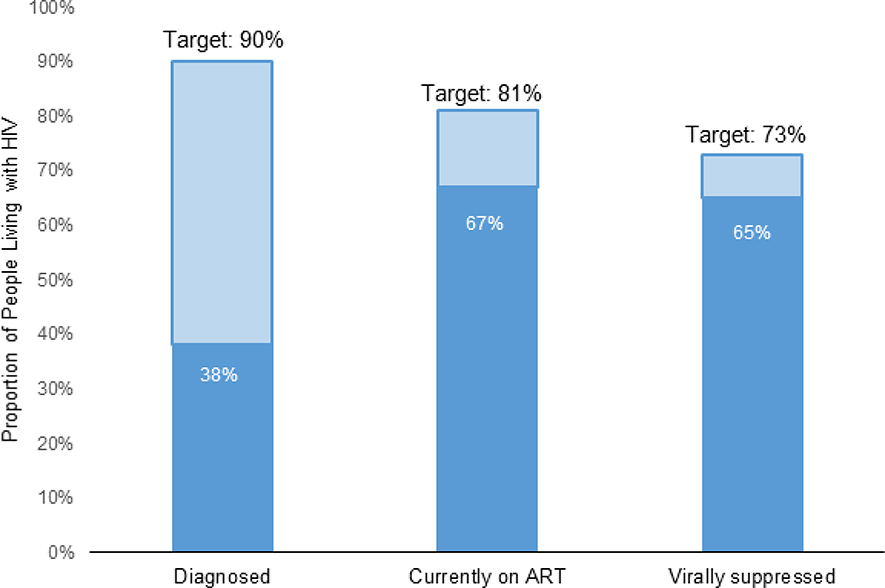

Over the past decade, China has made significant progress in reducing the spread of HIV [1]. In 2016, as part of their national strategy, the country adopted the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)’s 90–90-90 treatment targets, which calls for 90% of all people living with HIV to know their status, 90% of those who know their status to receive antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of those receiving ART to have suppressed viremia by 2020 [2]. Together, these targets allow for a serial attrition rate of 10% at each stage, ultimately leading to 73% of all people living with HIV (PLHIV) achieving viral suppression.

National surveillance data from China suggest that at the end of 2015, 68% of all PLHIV knew their HIV status, 67% of these were on ART, and 44% of these were virally suppressed [3]. Engaging members of key populations in the HIV care continuum has been challenging, particularly among men who have sex with men (MSM). MSM in China still have a high HIV incidence [4–7]. Despite comprising only 2–4% of the total population in China, MSM represent approximately 25.8% of all new infections [8]. Moreover, among Chinese MSM, only 38% knew their HIV status, 67% of these were on ART, and 65% were virally suppressed (Figure 1) [4, 9].

Figure 1.

Proportions of people living with HIV meeting the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets. Estimates of proportions tested and diagnosed with HIV from Zou H et al. [9]; estimates of proportions treated and suppressed from Ma Y et al. [3].

HIV surveillance data suggest a higher HIV incidence among young MSM (younger than 25 years old) and older MSM (older than 45 years old) [5, 10–11]. Limited sexual health education related to sexual minorities in China may contribute to onward HIV transmission [11]. Meanwhile, high rates of condomless sex have been noted among older MSM [7]. These age-related disparities in HIV incidence may suggest the need for interventions tailored to age subgroups.

In this article, we review literature on progress towards UNAIDS 90–90-90 targets for HIV prevention and treatment among Chinese MSM.

The first 90: HIV testing, and HIV prevention

Increasing HIV testing rates among Chinese MSM is a critical first step in the HIV care continuum. In this section, we highlight strategies that have been used in China to reach the first 90, as well as other key approaches to HIV prevention in China.

HIV testing

Many public health interventions have focused on increasing HIV testing among MSM [12–13]. A systematic review estimated that less than half of Chinese MSM had HIV tested in the past year [9]. Previous research has linked lower rates of HIV testing among Chinese MSM to socio-structural determinants of health, including fear of stigma and discrimination, low self-perception of HIV risk, and concerns about confidentiality in public settings [9, 14]. Determinants that influenced greater uptake of HIV testing included higher educational level, exposure to AIDS educational interventions, and disclosure of sexual orientation [13, 15]. There are two types of HIV testing: facility-based HIV testing and HIV self-testing (HIVST).

Facility-based HIV testing

The Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides free facility-based HIV testing through various sites, including voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) clinics, community health centers, and community-based organizations (CBOs), as well as free Western Blot confirmatory services at select CDC sites [19–20]. HIV testing in hospitals, however, incurs out-of-pocket costs for patients [16, 21]. For example, in 2018, the cost of HIV testing in Chinese hospitals was approximately 15 USD (100 RMB) [22]. As a result, many Chinese MSM prefer community-based settings for HIV testing [23], which, in addition to offering free testing, also have a higher case yield [17–18]. To address structural challenges that reduce the likelihood that MSM will engage in HIV testing, there has been in increase in collaborative efforts among several Chinese CDCs, hospitals, and CBOs to facilitate more comprehensive HIV testing services for MSM [24–26]. Still, many challenges remain that impede uptake of HIV testing among MSM [27–28]. Despite the many benefits associated with facility-based HIV testing (e.g., better connection to clinical follow-up and related HIV prevention services) [29–30], there are lingering concerns about stigma and discrimination, lack of confidentiality, and service quality [31–32].

HIVST

HIVST, a method in which a person performs their own HIV test by collecting a blood or saliva sample and interprets the test results, may overcome some of the barriers of facility-based HIV testing. HIVST offers a more rapid, convenient, confidential, and accessible approach to HIV testing [33–34]. Despite support from the World Health Organization and the Chinese Food and Drug Administration [35–36], HIVST is still an emerging alternative to facility-based testing in China. Most CDCs have yet to develop official HIVST-related guidelines or policies to promote HIVST uptake and facilitate broader access [54].

There are two HIVST options, blood-based and saliva-based tests. In China, MSM often prefer blood-based HIVST kits because of their higher sensitivity [38–39]. In recent years, the number of MSM using HIVST has substantially grown. In 2015, less than a third of MSM reported ever using HIVST [39]. Another study conducted in 2017 found that nearly half of men who participated in a HIVST intervention in urban China reported actually using the HIVST kits [40].

Digital interventions to extend the reach of HIV testing have been developed in various cities in China (Table 1). Several observational studies [42–44] and randomized controlled trials [41, 45–46] suggest that digital interventions may increase HIV testing uptake among MSM in China [40, 46]. An observational study found a large increase in facility-based HIV testing after a social networking application organized an HIV testing campaign [45]. Another study used crowdsourcing to create community-based HIV self-testing services [40]. A pragmatic randomized controlled trial found that a crowdsourced intervention was more effective compared with traditional strategies for increasing HIV testing among Chinese MSM [46].

Table 1.

Digital interventions to promote HIV testing among MSM in China

| Pilot | Organizers | Digital component and function | Financing | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crowdsourcing | MSM CBO, CDC, and research team | WeChat used to solicit creative ideas to deliver HIVST to MSM as part of open challenges and designathons; messages disseminated through WeChat | Free test kits supported by research study | Tang et al. 2018, PLoS Medicine [40]; Tucker et al. 2018, BMJ Innovations [82] |

| Public online self-testing | MSM CBO and CDC partnership | WeChat platform used to promote HIVST, arrange appointments for in-person testing, and send self-test kits through the mail; some programs offer self-collection only | Refundable deposit, supported by CDC | Zhong et. al. 2016, HIV Medicine [43]; Wu et al. 2019, IAS [85] |

| Company online self-testing | Pharmaceutical company | Online e-commerce platform (Jingdong) is used to market and distribute HIV self-test kits directly to MSM and others. | Users pay for self-test kits | Liu et al. 2015, CROI [86] |

| Social network | Gay social networking app with MSM CBOs and CDC partners | Online campaigns to promote facility-based testing at selected CBO sites; targeted livestreaming and banner advertisements nationwide | Free tests supported by CDC | Wang L et al. 2019 [12] |

HIV prevention

The Chinese national guidelines for HIV prevention highlight the importance of using multidimensional prevention strategies to engage Chinese MSM in the HIV care continuum [37]. Traditional HIV prevention strategies have often focused on unidimensional behavioral interventions, such as peer education, community services, and condom promotion [37]. However, given the heterogeneity of behavioral preferences among MSM, developing HIV prevention packages tailored for MSM subgroups may be more effective [10, 47–49]. High levels of internet use among Chinese MSM enable researchers to use digital platforms to solicit feedback from potential end users and tailor HIV prevention programs accordingly [40]. In this section, we highlight key research and emerging HIV prevention tools employed to engage Chinese MSM in the HIV prevention continuum.

Condom promotion interventions

Condom promotion interventions are critical to HIV prevention strategies [50–51]. Many behavioral interventions have effectively promoted condom use among Chinese MSM [49]. Moreover, condom use is associated with both individual (e.g. age, educational level, psychosocial problems, earlier sexual experience) and partner-level characteristics (e.g. types of partners, number of partners) [47, 53–54]. The Chinese CDC supports digital health approaches to increase condom use among MSM [37]. One randomized control trial showed condomless sex decreased after MSM who watched a video and received additional counseling [55]. Another randomized controlled trial found that a crowdsourced video increased condom use among MSM in China [56].

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

PrEP, a tenofovir-based antiretroviral drug that can reduce one’s risk of acquiring HIV by more than 90% when taken as prescribed, is an important biomedical HIV prevention tool [57–58]. Despite its promise and benefits, PrEP has limited uptake and coverage in China. Only 1% to 2.5% of Chinese MSM reported a history of PrEP use [58–59]. Low PrEP uptake among Chinese MSM may be attributed to a number of socio-structural factors, including lack of access, low PrEP awareness (i.e., only about 22% of MSM in China had heard about PrEP), low perceived HIV risk, concerns about drug side effects, and PrEP stigma [59–61]. In 2019, PrEP is only offered at private healthcare facilities and pharmacies in China and is not covered by health insurance [59, 62]. However, some Chinese MSM gain access to PrEP by purchasing the drug on the Internet or as medical tourists to neighboring countries [59, 63]. The cost of PrEP has also been a significant barrier to accessing the drug. In private clinics in mainland China, for example, the cost of PrEP is approximately US$300 per month [63]. In Hong Kong, the costs of PrEP may exceed US$1,000 per month [59].

The second 90: HIV treatment

National data on HIV outcomes in China indicate that progression along the HIV treatment continuum has continuously improved over the past 30 years [3]. In this section, we share research describing advances toward the second step of 90–90-90 targets for Chinese MSM, which focuses on HIV treatment and includes linkage and retention in HIV care.

Linkage to care

Assessing the uptake of HIV services is a critical component of monitoring and evaluating intervention efforts aimed at improving health-related outcomes among Chinese MSM living with HIV. Previous research has suggested that linking MSM to HIV care has improved dramatically over the past decade, with one longitudinal study showing an increase from 69% in 2008 to 89% in 2014 [64]. In this study of 1974 MSM in Guangzhou, 89% of those diagnosed with HIV who used facility-based testing were linked to care in 2014 [64]. Moreover, from the time of HIV diagnosis, the researchers found that 78% were linked to care within one month and 84% within three months [64].

The location in which Chinese MSM test for HIV may play an important role in linkage to care. Two studies found that MSM who were tested at MSM CBOs or voluntary counseling and testing sites were more likely to be linked to HIV care than those testing at hospitals [64–65]. This observed difference may be related to CBO peer outreach that inspires greater trust in services.

Retention in care

Previous research has suggested that the majority of those diagnosed with HIV are retained in HIV care in the short-term; however, long-term retention has been a challenge [64, 66]. One longitudinal study found that the rate of retention in HIV care prior to ART initiation (defined as receiving two or more CD4+ tests in one year, at least three months apart) declined over time, beginning at 75% in year one and dropping to 35% in year five [64]. Post-ART retention (defined as receiving two or more CD4+ tests after ART initiation in one year, at least three months apart) in HIV care was similar, such that 71% were retained in care in year one, but only 46% of these were retained in year two.

Socio-structural determinants of healthcare linkage and retention

The success of efforts to improve linkage and retention in HIV care among Chinese MSM may be influenced by socio-structural determinants of healthcare engagement. Several qualitative studies have identified determinants that negatively impact Chinese MSM’s ability to link to care, including: HIV-related stigma and discrimination, homophobia, low quality HIV care services, and lack of confidentiality at local clinics [50, 52–54]. These barriers also overlap with those associated with retention in HIV care [64]. One study, for example, found that younger MSM were less likely to be retained in HIV care than older MSM [64]. Moreover, this study found also that MSM with higher CD4+ counts were less likely to be retained in care than their peers.

The third 90: ART initiation & viral suppression

Compared to the general population, Chinese MSM show faster disease progression from HIV to AIDS, a faster decline in CD4+ counts prior to ART initiation, and a slower increase in CD4+ counts after ART initiation [67]. For these reasons, early ART initiation may be critical in this population.

ART initiation

Early ART initiation is an important step in the progression towards UNAIDS targets. Compared to other members of key populations, Chinese MSM are less likely to initiate ART [68]. Moreover, research concerning the rate of ART uptake among Chinese MSM has been mixed, with rates of ART initiation ranging between 26% and 92% depending upon various conditions [69–70]. One study, for example, found that the implementation of treatment as prevention strategies (i.e., approaches meant to control HIV transmission by early ART initiation to facilitate rapid viral suppression) increased ART coverage from 61% to 92% [70]. Early ART initiation has been linked to various positive outcomes, including higher rates of retention in HIV care (i.e., for those initiating within 30 days of a HIV diagnosis) and lower risk of treatment failure [71–73]. Delays in ART initiation, on the other hand, are frequently associated with an AIDS diagnosis, or having an initial CD4+ count of less than 200/mm3 within a year after initial diagnosis [74]. One study, for example, found that, between 2006 and 2014, 34% of Chinese PLHIV had received a late diagnosis [74].

There are number of barriers associated with ART initiation in China. Notably, the HIV testing and linkage process may be burdensome to newly diagnosed MSM, as one must attend several appointments prior to being approved to initiate ART [105]. For example, after an initial HIV test, patients must also seek confirmatory testing using the Western Blot. Next, they must wait for the Chinese Centers for Disease Control to contact them about scheduling a follow-up appointment date to monitor immunologic status [75].

Viral suppression and intervention approaches

Updated data on rates of ART adherence and viral suppression are difficult to obtain in China [76]. As previously reported, one study suggested that, at the end of 2015, only 44% of people on ART achieved virological suppression [63]. To accurately monitor progress towards 90–90-90 targets and ensure that current approaches to HIV intervention are effective, more data are needed.

Several HIV interventions have focused on multiple steps of the HIV care continuum, including HIV testing, linkage, retention, and adherence [60, 77]. One4All, for example, was an intervention based in Guangxi in which 12 hospitals were randomized to either standard of care or a HIV services model that integrated rapid, point-of-care HIV screening, and CD4+ and viral load testing to assess the impact of a patient-centered approach on testing completeness, ART initiation, and viral load suppression [77]. Results indicated that intervention participants were more likely to achieve testing completeness within 30 days and had fewer deaths than their peers in the standard of care arm.

Discussion

Over the past decade, China has made significant strides towards achieving UNAIDS 90–90-90 targets for HIV prevention and treatment; however, persistent gaps at each stage of the HIV care continuum have limited progress. Advances in digital health within the past decade offer promising opportunities to effect change at each stage of the care continuum and could potentially help China move closer to the global goal of ending AIDS in the country by 2030.

Digital health interventions, for example, have helped to increase both HIV facility-based testing and HIV self-testing among MSM [45, 78]. Given that many MSM do not disclose their sexual orientation to physicians or other health providers [79], digital health interventions may be useful for enhancing HIV service delivery. However, socio-structural determinants that influence the uptake of HIV testing must be addressed, including concerns regarding the protection of data shared on virtual platforms. As such, appropriate measures to ensure privacy and create people-centered services will be important. Some of the digital HIV testing promotion methods identified in China (Table 1) may be relevant in other low- and middle-income countries in which MSM are often online.

Lack of PrEP demonstration projects are another key issue. PrEP uptake in Chinese MSM remains extremely low. The high interest in PrEP, alongside medical tourism to nearby countries, suggest an unmet demand for these services. National guidelines supporting PrEP use, regulatory approval of oral PrEP, and further implementation projects are needed. Research modeling the potential impact of PrEP on HIV incidence among Chinese MSM could spur policy change.

National data on HIV outcomes in China indicate that progress towards the second and third 90, which includes linkage and retention in HIV care, and ART initiation and viral suppression, has improved over the past 30 years [63]. Still, it lags behind that of progress towards the first 90, with many people being lost to the HIV care continuum at stage one due to either a lack of HIV testing or lack of confirmatory HIV testing following one’s initial results. HIV testing and treatment protocols in China can be cumbersome; as a result, simplified test and treat interventions are needed to prevent poor outcomes among Chinese MSM, including reducing their mortality rates [80]. Comprehensive interventions that address socio-structural barriers at each stage of the HIV care continuum are crucial to our efforts of achieve HIV control [64].

Lastly, age-specific interventions may be important for achieving UNAIDS goals among Chinese MSM, as there are high-risk subgroups of MSM at both ends of the age spectrum with behaviors and preferences that differ from each other. HIV has become one of the most common causes of death among young people in China [81]. A crowdsourcing approach may be useful for tailoring HIV prevention and intervention strategies to be more youth-friendly [40].

Conclusions

China has made progress in its efforts to reach UNAIDS’ 90–90-90 HIV prevention and treatment targets among MSM. However, many socio-structural barriers persist at each stage of the HIV care continuum, leading to substantial levels of attrition, and the risk of forward HIV transmission. Comprehensive interventions, many of which utilize digital interventions, have been effective in HIV prevention [83]; however, more work is needed to evaluate their cost-effectiveness in HIV treatment. Still, there are many data gaps that make nationwide analyses challenging. Further research and implementation of MSM-focused programs is urgently needed.

References

- 1.Avert. HIV and AIDS in China. 2019. Available at: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/asia-pacific/china. Accessed 23 July 2019.

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).90–90-90 an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf. Accessed 25 April 2019.

- 3.Ma Y, Dou Z, Guo W, Mao Y, Zhang F, McGoogan JM, et al. The human immunodeficiency virus care continuum in China: 1985–2015. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;66(6):833–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu H, Liu X, Zhang Z, Xu X, Shi L, Fu G, et al. Increasing HIV Incidence among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Jiangsu Province, China: Results from Five Consecutive Surveys, 2011–2015. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2016;13(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Yang X, Zhang Z, Wang Z, Qi X, Ruan Y, et al. Incidence of Co-Infections of HIV, Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 and Syphilis in a Large Cohort of Men Who Have Sex with Men in Beijing, China. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu J-J, Tang W-M, Zou H-C, Mahapatra T, Hu Q-H, Fu G-F, et al. High HIV incidence epidemic among men who have sex with men in china: results from a multi-site cross-sectional study. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2016;5(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Q, Sun Y, Sun W, Hao M, Li G, Su X, et al. Trends of HIV incidence and prevalence among men who have sex with men in Beijing, China: Nine consecutive cross-sectional surveys, 2008–2016. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 2015 China AIDS Response Progress Report. 2015. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/CHN_narrative_report_2015.pdf. Accessed 7 February 2019.

- 9.Zou H, Hu N, Xin Q, Beck J. HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS and behavior. 2012;16(7):1717–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li YZ, Xu JJ, Qian HZ, You BX, Zhang J, Zhang JM, et al. High prevalence of HIV infection and unprotected anal intercourse among older men who have sex with men in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases. 2014;14:531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao X, Wang Z, Hu Q, Huang C, Yan H, Wang Z, et al. HIV incidence is rapidly increasing with age among young men who have sex with men in China: a multicentre cross-sectional survey. HIV medicine. 2018;19(8):513–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Podson D, Chen Z, Lu H, Wang V, Shepard C, et al. Using Social Media To Increase HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - Beijing, China, 2013–2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019;68(21):478–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ren XL, Mi GD, Zhao Y, Rou KM, Zhang DP, Geng L, et al. [The situation and associated factors of facility-based HIV testing among men who sex with men in Beijing]. Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine]. 2017;51(4):341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Z, Lau JTF, She R, Ip M, Jiang H, Ho SPY, et al. Behavioral intention to take up different types of HIV testing among men who have sex with men who were never-testers in Hong Kong. AIDS care. 2018;30(1):95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li R, Pan X, Ma Q, Wang H, He L, Jiang T, et al. Prevalence of prior HIV testing and associated factors among MSM in Zhejiang Province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC public health. 2016;16(1):1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma F, Lv F, Xu P, Zhang D, Meng S, Ju L, et al. Task shifting of HIV/AIDS case management to Community Health Service Centers in urban China: a qualitative policy analysis. BMC health services research. 2015;15:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan S, Wang S, Deng S, Liao Q. Service efficiency of community-based organizations for HIV infected persons and AIDS patients. Practical Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2014(3):70–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hao Y, Shan D, Fu X, Qi J, Meng S, Li C, et al. [The feasibility of Community Health Service Center-based HIV prevention and intervention in China]. Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine]. 2014;48(5):386–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. Information about HIV testing. 2018. Available from: http://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/azb/zstd/201811/t20181116_197341.html. Accessed on July 1, 2019.

- 20.Liu SL, Xu P, Qi Y, Lu F. Analysis of the policy implication of real name HIV testing. Chin J AIDS STD. 2012(5):327–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li R, Zhao G, Li J, McGoogan JM, Zhou C, Zhao Y, et al. HIV screening among patients seeking care at Xuanwu Hospital: A cross-sectional study in Beijing, China, 2011–2016. PloS one. 2018;13(12):e0208008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC. The cost of HIV testing in China. 2018. [Available from: https://www.hiv-cdc.com/aizizhishi/725.html.

- 23.Han L, Wei C, Muessig KE, Bien CH, Meng G, Emch ME, et al. HIV test uptake among MSM in China: Implications for enhanced HIV test promotion campaigns among key populations. Global public health. 2017;12(1):31–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang X, Zhang J, Pan R, Yu X, Chen K, Zhang J, et al. An analysis on effects of cooperation with community-based organizations in HIV testing mobilization and follow up among men who have sex with men. Chin J AIDS STD. 2015(1):62–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization [WHO]. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services: 5Cs: consent, confidentiality, counselling, correct results and connection 2015. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang XF, Wu ZY, Tang ZZ, Nong QX, Li YQ. [Acceptability of HIV testing using oral quick self-testing kit in men who have sex with men]. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2018;39(7):937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren XL, Mi GD, Zhao Y, Rou KM, Zhang DP, Geng L, et al. [The situation and associated factors of facility-based HIV testing among men who sex with men in Beijing]. Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine]. 2017;51(4):341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zun-You WU. The progress and challenges of promoting HIV/AIDS 90–90-90 strategies in China. J Chinese Journal of Disease Control Prevention. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang X, Zhang J, Pan R, Yu X, Chen K, Zhang J, et al. An analysis on effects of cooperation with community-based organizations in HIV testing mobilization and follow up among men who have sex with men. Chin J AIDS STD. 2015(1):62–4. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo X, Xu X, Fan C, Peng L, Peng C, Yang L. An exploration of expansion of HIV counselling and testing comprehensive services in general hospitals. Chin J AIDS STD. 2014(6):449–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma M, Ying R, Tarr G, Barnabas R: Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature 2015, 528(7580):S77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang XF, Wu ZY, Tang ZZ, Nong QX, Li YQ. [Acceptability of HIV testing using oral quick self-testing kit in men who have sex with men]. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2018;39(7):937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization [WHO]. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services: 5Cs: consent, confidentiality, counselling, correct results and connection 2015. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang XF, Wu ZY, Tang ZZ, Nong QX, Li YQ. [Acceptability of HIV testing using oral quick self-testing kit in men who have sex with men]. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi = Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2018;39(7):937–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Organization WH. Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification: supplement to consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services: World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan L, Xiao P, Yan H, Huan X, Fu G, Li J, et al. The advance of detection technology of HIV self-testing. Chin J Prev Med. 2017;51(11):1053–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Guidelines for HIV/AIDS prevention among men who have sex with men 2016. 2016Available at: [http://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/azb/jszl_2219/201609/W020160922471323108736.pdf]. Accessed on July 1, 2019.

- 38.Wei C, Yan L, Li J, Su X, Lippman S, Yan H. Which user errors matter during HIV self-testing? A qualitative participant observation study of men who have sex with men (MSM) in China. BMC public health. 2018;18(1):1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin Y, Tang W, Nowacki A, Mollan K, Reifeis SA, Hudgens MG, et al. Benefits and Potential Harms of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Self-Testing Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in China: An Implementation Perspective. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2017;44(4):233–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang W, Wei C, Cao B, Wu D, Li KT, Lu H, et al. Crowdsourcing to expand HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: A closed cohort stepped wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS medicine. 2018;15(8):e1002645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Z, Lau JTF, Ip M, Ho SPY, Mo PKH, Latkin C, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating Efficacy of Promoting a Home-Based HIV Self-Testing with Online Counseling on Increasing HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and behavior. 2018;22(1):190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang L, Podson D, Chen Z, Lu H, Wang V, Shepard C, et al. Using Social Media To Increase HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - Beijing, China, 2013–2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019;68(21):478–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhong F, Tang W, Cheng W, Lin P, Wu Q, Cai Y, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of a social entrepreneurship testing model to promote HIV self-testing and linkage to care among men who have sex with men. HIV medicine. 2017;18(5):376–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng WB, Xu HF, Zhong F, Cai YS, Chen XB, Meng G, et al. [Application of “ Internet Plus” AIDS prevention services among men who have sex with men in Guangzhou, China: results from 2010 to 2015]. Zhonghua yu fang yi xue za zhi [Chinese journal of preventive medicine]. 2016;50(10):853–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu X, Zhang W, Operario D, Zhao Y, Shi A, Zhang Z, et al. Effects of a Mobile Health Intervention to Promote HIV Self-testing with MSM in China: A Randomized Controlled Trial. AIDS and behavior. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang W, Han L, Best J, Zhang Y, Mollan K, Kim J, et al. Crowdsourcing HIV Test Promotion Videos: A Noninferiority Randomized Controlled Trial in China. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016;62(11):1436–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng W, Tang W, Zhong F, Babu GR, Han Z, Qin F, et al. Consistently high unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) and factors correlated with UAI among men who have sex with men: implication of a serial cross-sectional study in Guangzhou, China. BMC infectious diseases. 2014;14:696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye S, Yin L, Amico R, Simoni J, Vermund S, Ruan Y, et al. Efficacy of peer-led interventions to reduce unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(3):e90788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang Z, Wang M, Fu L, Fang Y, Hao J, Tao F, et al. Intervention to increase condom use and HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China: a meta-analysis. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2013;29(3):441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu Z, Xu J, Liu E, Mao Y, Xiao Y, Sun X, et al. HIV and syphilis prevalence among men who have sex with men: a cross-sectional survey of 61 cities in China. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;57(2):298–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu J, Hu Y, Jia Y, Su Y, Cui H, Liu H, et al. Prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in China: an updated meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(5):e98366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li R, Wang H, Pan X, Ma Q, Chen L, Zhou X, et al. Prevalence of condomless anal intercourse and recent HIV testing and their associated factors among men who have sex with men in Hangzhou, China: A respondent-driven sampling survey. PloS one. 2017;12(3):e0167730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang H, Chen X, Li J, Tan Z, Cheng W, Yang Y. Predictors of condom use behavior among men who have sex with men in China using a modified information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model. BMC public health. 2019;19(1):261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang J, Xu H, Li S, Cheng W, Gu Y, Xu P, et al. The characteristics of mixing patterns of sexual dyads and factors correlated with condomless anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in Guangzhou, China. BMC public health. 2019;19(1):722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hao C, Huan X, Yan H, Yang H, Guan W, Xu X, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the relative efficacy of enhanced versus standard voluntary counseling and testing on promoting condom use among men who have sex with men in China. AIDS and behavior. 2012;16(5):1138–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tang W, Mao J, Liu C, Mollan K, Zhang Y, Tang S, et al. Reimagining Health Communication: A Noninferiority Randomized Controlled Trial of Crowdsourced Intervention in China. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2019;46(3):172–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyers K, Wu Y, Qian H, Sandfort T, Huang X, Xu J, et al. Interest in Long-Acting Injectable PrEP in a Cohort of Men Who have Sex with Men in China. AIDS and behavior. 2018;22(4):1217–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ding Y, Yan H, Ning Z, Cai X, Yang Y, Pan R, et al. Low willingness and actual uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. Biosci Trends. 2016;10(2):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Z, Lau JTF, Fang Y, Ip M, Gross DL. Prevalence of actual uptake and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong, China. PloS one. 2018;13(2):e0191671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y, Peng B, She Y, Liang H, Peng HB, Qian HZ, et al. Attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in western China. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2013;27(3):137–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han J, Bouey JZ, Wang L, Mi G, Chen Z, He Y, et al. PrEP uptake preferences among men who have sex with men in China: results from a National Internet Survey. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2019;22(2):e25242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei C, Raymond HF. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men in China: challenges for routine implementation. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2018;21(7):e25166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.PrEPMAP. Your guide to PrEP in Asia and the Pacific: PrEPMAP; 2019. [Available from: https://www.prepmap.org/prep_status_by_country.

- 64.Wong NS, Mao J, Cheng W, Tang W, Cohen MS, Tucker JD, et al. HIV Linkage to Care and Retention in Care Rate Among MSM in Guangzhou, China. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(3):701–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ren X-L, Wu Z-Y, Mi G-D, McGoogan JM, Rou K-M, Zhao Y, et al. HIV care-seeking behaviour after HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men in Beijing, China: a cross-sectional study. Infectious Diseases of Poverty. 2017;6(1):112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang J, Xu J-j, Song W, Pan S, Chu Z-x, Hu Q-h, et al. HIV Incidence and Care Linkage among MSM First-Time-Testers in Shenyang, China 2012–2014. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(3):711–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yan H, Yang H, Li J, Wei C, Xu J, Liu X, et al. Emerging disparity in HIV/AIDS disease progression and mortality for men who have sex with men, Jiangsu Province, China. AIDS and behavior. 2014;18 Suppl 1:S5–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu Y, Ruan Y, Vermund SH, Osborn CY, Wu P, Jia Y, et al. Predictors of antiretroviral therapy initiation: a cross-sectional study among Chinese HIV-infected men who have sex with men. BMC infectious diseases. 2015;15:570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y, Ruan Y, Vermund SH, Osborn CY, Wu P, Jia Y, et al. Predictors of antiretroviral therapy initiation: a cross-sectional study among Chinese HIV-infected men who have sex with men. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2015;15(1):570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He L, Yang J, Ma Q, Zhang J, Xu Y, Xia Y, et al. Reduction in HIV community viral loads following the implementation of a “Treatment as Prevention” strategy over 2 years at a population-level among men who have sex with men in Hangzhou, China. BMC infectious diseases. 2018;18(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ford N, Migone C, Calmy A, Kerschberger B, Kanters S, Nsanzimana S, et al. Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. 2018;32(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bor J, Fox MP, Rosen S, Venkataramani A, Tanser F, Pillay D, et al. Treatment eligibility and retention in clinical HIV care: a regression discontinuity study in South Africa. 2017;14(11):e1002463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao Y, Wu Z, McGoogan JM, Sha Y, Zhao D, Ma Y, et al. Nationwide cohort study of antiretroviral therapy timing: treatment dropout and virological failure in China, 2011–2015. 2018;68(1):43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tang H, Mao Y, Tang W, Han J, Xu J, Li J. “Late for testing, early for antiretroviral therapy, less likely to die”: results from a large HIV cohort study in China, 2006–2014. BMC infectious diseases. 2018;18(1):272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sun J, Liu L, Shen J, Chen P, Lu HJBid. Trends in baseline CD4 cell counts and risk factors for late antiretroviral therapy initiation among HIV-positive patients in Shanghai, a retrospective cross-sectional study. 2017;17(1):285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tang S, Tang W, Meyers K, Chan P, Chen Z, Tucker JD. HIV epidemiology and responses among men who have sex with men and transgender individuals in China: a scoping review. BMC infectious diseases. 2016;16(1):588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu Z, Tang Z, Mao Y, Van Veldhuisen P, Ling W, Liu D, et al. Testing and linkage to HIV care in China: a cluster-randomised trial. 2017;4(12):e555–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cao B, Saha PT, Leuba SI, Lu H, Tang W, Wu D, et al. Recalling, Sharing and Participating in a Social Media Intervention Promoting HIV Testing: A Longitudinal Analysis of HIV Testing Among MSM in China. AIDS and behavior. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tang W, Mao J, Tang S, Liu C, Mollan K, Cao B, Wong T, Zhang Y, Hudgens M, Qin Y, Han L. Disclosure of sexual orientation to health professionals in China: results from an online cross‐sectional study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2017;20(1):21416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tian T, Mijiti P, Bingxue H, Fadong Z, Ainiwaer A, Guoyao S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anal human papillomavirus infection among HIV-negative men who have sex with men in Urumqi city of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China. PloS one. 2017;12(11):e0187928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sun J, Yang WW, Zeng LJ, Geng MJ, Dong YH, Xing Y, Ma J, Li ZJ, Wang LP. Surveillance data on notifiable infectious diseases among students aged 6–22 years in China, 2011–2016. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi= Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2018. December;39(12):1589–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tucker JD, Tang W, Li H, Liu C, Fu R, Tang S, Cao B, Wei C, Tangthanasup TM. Crowdsourcing designathon: a new model for multisectoral collaboration. BMJ Innovations. 2018. April 1;4(2):46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cao B, Gupta S, Wang J, Hightow-Weidman LB, Muessig KE, Tang W, et al. Social Media Interventions to Promote HIV Testing, Linkage, Adherence, and Retention: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of medical Internet research. 2017;19(11):e394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu Z, Tang Z, Mao Y, Van Veldhuisen P, Ling W, Liu D, et al. Testing and linkage to HIV care in China: a cluster-randomised trial. The lancet HIV. 2017;4(12):e555–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu D, Tang W, Ong J, Smith MK, Ritchwood TD, Fu HT, Pan S & Tucker JD. Social-media based secondary distribution of HIV self-testing among Chinese men who have sex with men: a pilot implementation program assessment. Oral presentation at the 10th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2019), Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu F, Han L, Tang W, Huang S, Yang L, Zheng H, Yang B, Tucker JD. Availability and quality of online HIV self-test kids in China and the United States. Poster presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (2015), Seattle, Washington. [Google Scholar]