Abstract

CD8+ T cells controlling pathogens or tumors must function at sites where oxygen tension is frequently low, and never as high as under atmospheric culture conditions. However, T‐cell function in vivo is generally analyzed indirectly, or is extrapolated from in vitro studies under nonphysiologic oxygen tensions. In this study, we delineate the role of physiologic and pathologic oxygen tension in vitro during reactivation and differentiation of tumor‐specific CD8+ T cells. Using CD8+ T cells from pmel‐1 mice, we observed that the generation of CTLs under 5% O2, which corresponds to physioxia in lymph nodes, gave rise to a higher effector signature than those generated under atmospheric oxygen fractions (21% O2). Hypoxia (1% O2) did not modify cytotoxicity, but decreasing O2 tensions during CTL and CD8+ tumor‐infiltrating lymphocyte reactivation dose‐dependently decreased proliferation, induced secretion of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL‐10, and upregulated the expression of CD137 (4‐1BB) and CD25. Overall, our data indicate that oxygen tension is a key regulator of CD8+ T‐cell function and fate and suggest that IL‐10 release may be an unanticipated component of CD8+ T cell‐mediated immune responses in most in vivo microenvironments.

Keywords: CD8+ T cell, Oxygen, Hypoxia, IL‐10, T‐cell reactivation

Introduction

In a healthy physiologic context, oxygen tensions in mammalian tissues are tightly regulated, but still show significant variation both between tissues and within the same tissue (Supporting Information Fig. 1A) 1, 2, 3. However, oxygen tensions are far below physiologic values in different pathologic conditions, mostly involving inflammation 4, solid tumors 5, 6, and infections 7.

In contrast to sufficient oxygen supply (i.e. normoxia), oxygen deprivation (i.e. hypoxia) leads to cellular responses involving stabilization of HIFs (hypoxia‐inducible factors), transcription factors that are composed of an inducible α‐subunit (i.e. HIF‐1α, HIF‐2α, or HIF‐3α) together with a constitutive β‐subunit (i.e. HIF‐1β, HIF‐2β, or HIF‐3β) 8. Upon stabilization, HIFs transcribe various genes with HIF‐responsive elements in their promoter; these include those that increase angiogenesis (e.g. VEGF) and glucose metabolism (e.g. glucose transporters) 9. Interestingly, HIF‐1α and HIF‐2α can have unique, redundant, or opposing roles 9, 10. Furthermore, while HIF‐1α is described to be stabilized and active below 2% O2 in an acute manner, HIF‐2α has been shown to be stable below 5% O2 in a chronic manner 11, 12. However, although HIFs are central to many hypoxia responses, certain effects have been shown to be HIF‐independent 13, 14, 15. Intriguingly, HIF‐1α can also be involved in immune cell activation under atmospheric oxygen fractions (AtO2; i.e. 21%), as reported for macrophages and T cells 16, 17.

Hypoxia is an essentially in vivo microenvironmental phenomenon that is challenging to study and recapitulate in vitro. When exploring hypoxia, one has to compare hypoxic to normoxic conditioning. However, most published studies consider AtO2 as normoxia 1. This could lead to misinterpretation, as, for example, physiological oxygen fraction (physioxia) found in secondary lymphoid organs is close to 5% O2 and can induce differential T lymphocyte activation as compared to AtO2 in vitro 18, 19, 20. This highlights the necessity to not only use physioxia as a reference point to study hypoxia impact in vitro, but also to analyze cell physiology in general. Physioxia in tissues varies greatly: e.g. skin 1.1%, brain 4.4%, pulmonary alveoli 14.5% (Supporting Information Fig. 1A) 3. As a baseline for physioxia in healthy tissues, 5% O2 was previously used for assessing lymphocyte function 19; we also selected this compromise value for our study.

The impact of hypoxia and HIF has been intensively studied in the context of malignancy or infection and often positively correlated with pathogenesis. In cancer, hypoxia promotes tumor cell stemness, migration, invasiveness, metastasis, and resistance to radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and to CTL‐mediated killing [10, 21–25]. In viral infection, hypoxia increases viral replication and gene expression 26. To date, the impact of hypoxia on T cells implicated in anti‐tumor and anti‐viral immunity is not extensively described. Most studies focused on CD4+ T cells, without consensus regarding the effects. Earlier studies suggested a positive correlation between hypoxia and viability or proliferation 27, 28, more recent studies showed the opposite 29, 30. Hypoxia was also shown to increase Th17 and Treg polarization 31, 32. Concerning cytokine production, there are conflicting results for secretion of IL‐2, IFN‐γ, IL‐10, and IL‐1β 29, 30, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37. Overall, despite certain contradictions in this emerging research area, the knowledge base for CD4+ T cells is becoming more comprehensive. The impact of hypoxia and oxygen tensions on CD8+ T cells is restricted to a few interesting studies 17, 18, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42. However, there are many issues regarding the reactivation of already primed CD8+ T cells (hereafter considered as CTLs) that require further investigation. It is particularly important to understand CTL responses to hypoxia because, in contrast to certain Th subsets, these cells must function in the most oxygen‐deprived sites in the body (e.g. tumor bed, sites of infection).

In this study, we explored hypoxia impact on effector CD8+ T cells reactivated either under 5% (physioxia in many healthy tissues) or 1% O2 (hypoxia found in inflamed or tumoral sites) (Supporting Information Fig. 1B). Gene expression analysis of reactivated CTLs underlined the importance of using physioxia instead of AtO2 as a normoxia reference, as many genes described to be modulated under hypoxia were already regulated under physioxia. Our investigations of immune function under oxygen deprivation revealed that whereas hypoxia did not modify CTL killing capacities, it potently induced IL‐10 secretion upon reactivation, and dramatically decreased CTL expansion.

Results

Enhanced effector signature of CD8+ T cells primed under physioxia

We used CD8+ T cells from Pmel‐1 mice that carry a transgenic TCR directed against the immunodominant epitope of the tumor/self‐antigen gp100, allowing us to obtain a clonal population of naïve CD8+ T cells 43. To model a physiologic effector CD8+ T‐cell response, we first generated CTLs under physioxia (5% O2), as found in LNs, and compared them to CTLs generated under AtO2 (i.e. 21% O2). We performed this comparison because 21% O2 is commonly used during in vitro cell culture as a normoxic control to study hypoxia impact.

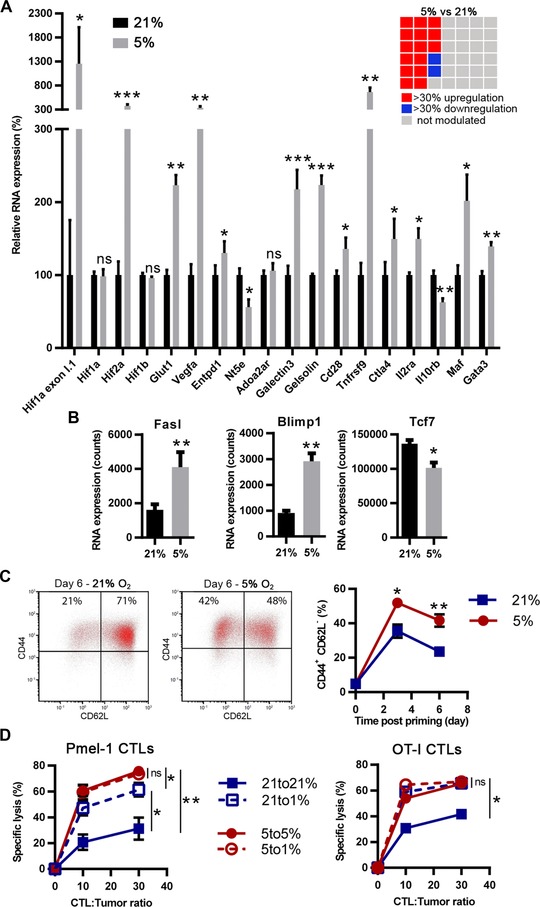

We analyzed the expression of a panel of 42 genes described to be either regulated under hypoxia, to be immune‐function related, or to be involved in cell survival (Supporting Information Table 1). Relative to 21% O2, the physioxic oxygen fraction (5% O2) that was used during CTL generation upregulated RNA expression of different genes described to be increased by hypoxia. These included hif1a exon I.1 (albeit weakly expressed, as judged by Nanostring absolute RNA counts (data not shown)), hif2a, vegfa, glut1, entpd1 (CD39), galectin3, gelsolin, and tnfrsf9 (CD137). However, hif1a, adora2a (A2AR), and hif1b were not modulated, hif3a was not expressed, while nt5e (CD73) was downregulated 11, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 (Fig. 1A). Several genes positively associated with CD8+ T cell survival and expansion were upregulated, including gata3, il2ra, and cd28 [51–53]. However, maf and ctla4, associated with increased apoptosis and immune regulation 54, 55, were also upregulated. It was noteworthy that CTLs generated under physioxia showed a higher effector profile, evidenced by blimp1 and fasl upregulation, and tcf7 downregulation (Fig. 1B). Consistent with these observations, CTLs generated under normoxia showed increase of the CD44+ CD62L‐ fraction (Fig. 1C) and a decrease of CD127 (IL‐7Rα) expression (Supporting Information Figs. 1C and 2A). This was not due to the CD8+ T‐cell clone used, as OT‐I CTLs and polyclonal CTLs from C57BL/6 gave the same results (Supporting Information Fig. 2B–D). Accordingly, CTLs generated under physioxia had increased killing capacities as compared to CTLs generated under AtO2 (Supporting Information Fig. 2E). We next investigated whether hypoxia (1% O2) could impact CTL lytic capacities. Independently of the oxygen fraction used during CTL generation, hypoxia during the cytotoxicity assay had no effect (Supporting Information Fig. 2E). As this assay implies a short‐term hypoxia exposure (4 h), we also preconditioned the CTLs three days before carrying out the killing assay. Interestingly, CTLs generated under AtO2 and that were preconditioned under hypoxia showed increased cytotoxicity (Fig. 1D). However, CTLs generated under physioxia and that were preconditioned under hypoxia did not augment their killing capacities. GranzymeB (GrB) was preferentially expressed by CTLs that were generated under physioxia as compared to those generated under AtO2 (Supporting Information Fig. 2F–G), consistent with the increase in effector versus memory differentiation that we observed. However, we did not observe any difference when CTLs were preconditioned or not under hypoxia. Therefore, hypoxia might improve CTL killing capacities of CTLs generated under AtO2 through a mechanism independent of GrB production.

Figure 1.

CTLs generated under physioxia have a higher effector profile than those generated under atmospheric oxygen fraction. (A and B) CTLs from Pmel‐1 splenocytes were generated under 21% (black bars) or 5% O2 (gray bars) and were analyzed for RNA expression. Results represent (A) the mean relative gene expression or (B) the RNA absolute count + SEM of five independent experiments (n = 5). The checkerboard represents the 42 genes analyzed (only genes modulated by more than 30% with a p < 0.05 are colored in red or blue). (C and D) CTLs from Pmel‐1 splenocytes were generated under O2 fractions as indicated and were analyzed for marker expression by flow cytometry. (C) CTLs were stained for CD62L and CD44, gated on live CD8+ cells, at day 0, day 3, and day 6 postpriming. Dot plots show one representative experiment at day. Line graph shows the mean percentage ± SEM CD44+ CD62L‐ cells among CTLs from at least four independent experiments (n ≥ 4). (D) CTLs generated under 21 and 5% were preconditioned for 3 days under 21 (“21 to 21%”), 5 (“5 to 5%”) or 1% (“21 to 1%” and “5 to 1%”) O2. The resulting CTLs were assessed for their capacity to kill EL‐4 tumor target cells pulsed with hgp100 (Pmel‐1 CTLs; n ≥ 4) or Ova peptide (OT‐I CTLs; n = 3) for 4 h under the oxygen fraction used for preconditioning. Results show the mean ± SEM specific lysis of tumor cells from at least three independent experiments. ns: not statistically significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (A, B: Three‐way ANOVA; C, D: Student's t‐test).

Hypoxia decreases expansion of reactivated CTLs

We next investigated the impact of oxygen tension on expansion of already primed CD8+ T cells. The impact of hypoxia on CD8+ T‐cell antitumor or antiviral responses is most critical to examine during CTL reactivation, such as occurs when already primed cells have migrated to nonlymphoid tissues to exert their effector functions in a potentially hypoxic microenvironment. To model this, CTLs generated under physioxia were reactivated either under physioxia (5% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). We also compared these results to CTLs generated and reactivated under AtO2 (Supporting Information Fig. 1B). As expected, one day postrestimulation HIF‐1α stabilization was regulated negatively by oxygen fraction (Supporting Information Fig. 3). However, two days postrestimulation its level decreased under low oxygen fraction while it was highly stabilized under AtO2; thus confirming previous results showing that HIFs are involved in TCR signaling. As found for priming of CD8+ T cells (data not shown), hypoxia dramatically decreased CTL expansion after reactivation (Fig. 2A). This was associated with reduced cell divisions and viability (Fig. 2B, C), with a trend toward more apoptosis (Fig. 2D). Similar expansion was obtained using OT‐I CD8+ T cells and also with polyclonal CTLs from C57BL/6 mice (Supporting Information Fig. 4A–D).

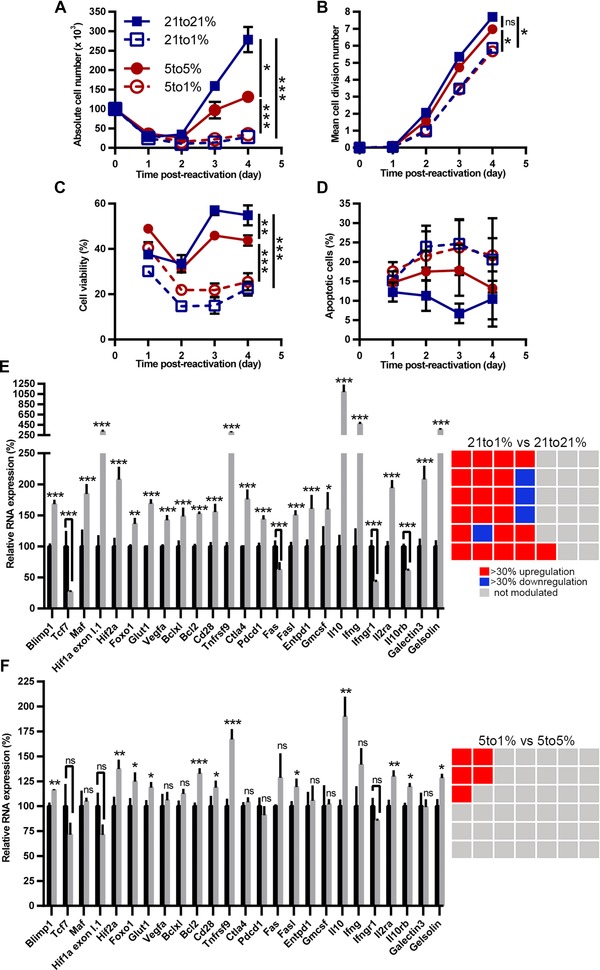

Figure 2.

Hypoxia modulates expansion and RNA profile of reactivated CTLs. CTLs generated under 21% (squares) or 5% (circles) O2 from Pmel‐1 splenocytes were reactivated for indicated times under 21% O2 (closed squares with solid line), 5% O2 (closed circles with solid line) or 1% O2 (open squares or open circles with dashed line). Results show (A) mean cell number, (B) mean cell division number, (C) mean cell viability, and (D) mean apoptotic cells ± SEM out of at least three independent experiments (n ≥ 3). CTLs generated under (E) 21% or (F) 5% O2 from Pmel‐1 splenocytes were reactivated for two days under indicated oxygen fractions. (E) RNA profile from CTLs reactivated under 21% (black bars) or 1% O2 (gray bars). (F) RNA profile from CTLs reactivated under 5% (black histograms) or 1% O2 (gray histograms). Results represent the mean relative gene expression + SEM out of four independent experiments (n = 4). The checkerboard represents the 42 genes analyzed (only genes modulated by more than 30% with a p < 0.05 are colored in red or blue). To display common genes modulated under each condition, genes composing the checkerboard are organized identically (in an arbitrary fashion). ns: not statistically significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, *** p <0.001 (A–D: Student's t‐test; E, F: Three‐way ANOVA).

Hypoxia differentially modulates gene expression when comparing to physioxia or atmospheric oxygen

We next determined the impact of hypoxia on gene expression by reactivated CTLs. Hypoxia highly impacted numerous genes (25/42) as compared to AtO2 (Fig. 2E). However, as compared to physioxia, hypoxia impacted one fifth of them (5/42), and to a lesser extent (Fig. 2F). CTLs reactivated for two days under hypoxia showed increased expression of il10 and tnfrsf9 (CD137), and to a lesser extent bcl2, hif2a, and il2ra (CD25). Of all genes analyzed, il10 was the most modulated under hypoxia, independently of the oxygen fraction used as normoxia reference. RNA expression kinetics for il10, ifng, tnfrsf9 (CD137), il2ra (CD25), and hif2a (Supporting Information Fig. 5A–E) indicated a strong upregulation of RNA levels by two days postreactivation, then a decrease, although hif2a RNA expression was more stable. For all these genes there was a negative correlation between oxygen fractions and RNA expression. Concerning bcl2 RNA (Supporting Information Fig. 5F), its expression was decreased from two days postreactivation, but it was more stable under hypoxia. In order to know whether these modulations were due to hypoxia itself or to a combination of hypoxia plus TCR stimulation, we analyzed expression of the same panel of genes by CTLs cultured for two days without stimulation (Supporting Information Fig. 6A–D).There was no upregulation of il10, hif2a, or il2ra, showing that hypoxia‐driven upregulation of these molecules is dependent on TCR stimulation. Interestingly, tnfrsf9 was upregulated when we compared CTLs cultured under 1% vs those cultured under 5% O2.

IL‐10 secretion by CTLs inversely correlates with oxygen fraction

We confirmed our results for key genes at the protein level. By flow cytometry, we observed an increase of CD137 (4‐1BB) and CD25 (IL‐2Rα) under hypoxia on reactivated CTLs (from Pmel‐1, OT‐I, and C57BL/6 mice), as compared to physioxia or AtO2 (Fig. 3A, B, Supporting Information Fig. 7A–D). Although Bcl‐2 was upregulated under hypoxia when compared to AtO2, there was no effect of hypoxia on Bcl‐2 levels if the comparison was made with physioxia (Supporting information Fig. 5G).

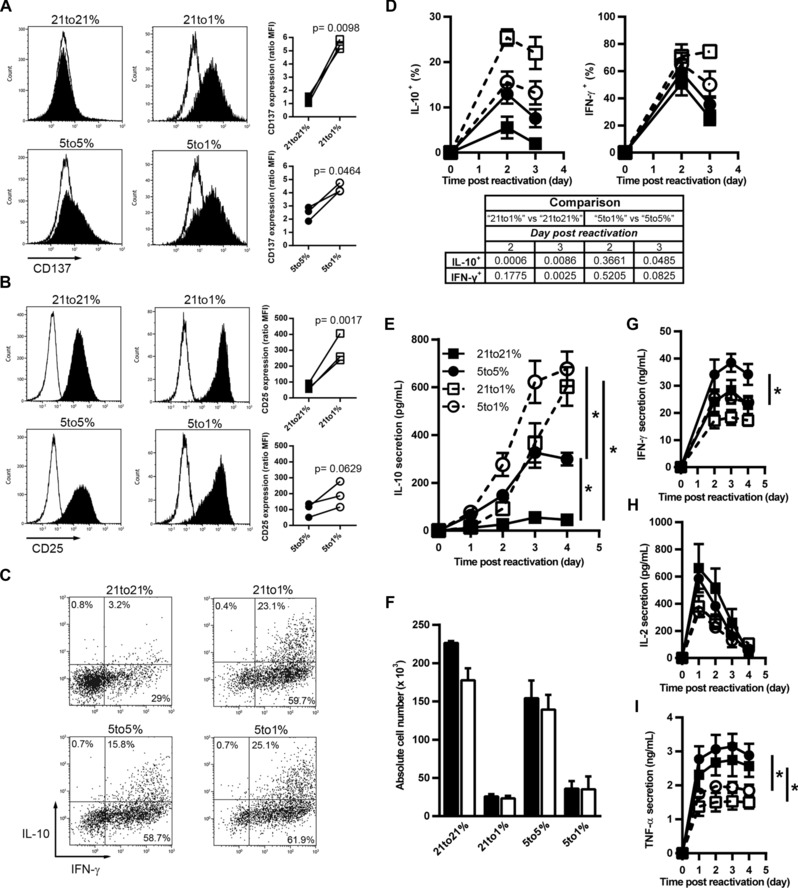

Figure 3.

Decreasing oxygen fraction promotes IL‐10 production by reactivated CTLs. CTLs were generated under 21% O2 and reactivated under 21% (21 to 21%) or 1% O2 (21 to 1%), or were generated under 5% O2 and reactivated under 5% (5 to 5%) or 1% (5 to 1%) O2. Four days post‐reactivation cell surface expression of (A) CD137 or (B) CD25 was assessed by flow cytometry. (A and B) Open histograms: control isotype staining; closed histograms: staining for the molecule of interest. Line graphs: median fluorescence intensity from three independent experiments (n = 3). (C) Dot plots: IL‐10 and IFN‐γ intracellular staining from CTLs reactivated for two days. (D) Percentage of IL‐10+ or IFN‐γ+ CTLs from CTLs generated under 21% (squares) or 5% O2 (circles) that were reactivated under 21% (closed squares with solid line), 5% (closed circles with solid line) or 1% O2 (open squares and open circles with dashed line), mean ± SEM of 4–5 independent experiments (n ≥ 4). The table represents the p‐value obtained by two‐tailed Student's t‐test calculations. Comparison were made between CTLs generated at 21% and reactivated at 1% versus CTLs generated at 21% and reactivated at 21% O2 (“21 to 1%” versus “21 to 21%”) or between CTL generated at 5% and reactivated at 1% versus CTL generated at 5% and reactivated at 5% O2 (“5 to 1%” versus “5 to 5%”). Mean cytokine secretion of (E) IL‐10, (G) IFN‐γ, (H) IL‐2, and (I) TNF‐α ± SEM out of three independent experiments (n = 3).*p < 0.05. (F) Cell yield from CTLs reactivated for four days in the presence of IL‐10 blocking antibody (open bars) or isotype control (closed bars), mean + SD of two independent experiments (n = 2). *p < 0.05 (Student's t‐test).

To further explore the unexpected production of IL‐10 by CD8+ T cells under low oxygen tensions, we analyzed intracellular IL‐10 production by reactivated CTLs. Lowering oxygen tension increased the fraction of IL‐10 producing CTLs (Fig. 3C, D), the IL‐10‐positive fraction also coexpressed IFN‐γ. However, whereas hypoxia augmented the IFN‐γ‐positive fraction as compared to AtO2, it did not significantly increase this fraction as compared to physioxia (Fig. 3D). Analysis of secreted IL‐10 indicated weak secretion under AtO2, moderate induction by physioxia, and potent induction by hypoxia (Fig. 3E). Using CD8+ T cells from OT‐I and C57BL/6 mice yielded the same results (Supporting Information Fig. 7E and G). Thus, these data suggest that IL‐10 is a typical CTL cytokine following reactivation under physioxia, and that its secretion is further increased under hypoxia. However, IL‐10 is not a cytokine secreted after primary activation of naïve CD8+ T cells, even when primed under physioxia or hypoxia (data not shown). We next tested whether IL‐10 secretion was responsible for the decreased cell expansion under hypoxia; using an IL‐10‐blocking antibody during CTL reactivation did not restore expansion under hypoxia (Fig. 3F). Thus, hypoxia impacts on the cytokine secretion profile of CTLs, but at least for IL‐10, without autocrine consequences. We did not observe any hypoxia‐related increase in expression of IFN‐γ, IL‐2, or TNF‐α (Fig. 3G–I, Supporting Information Fig. 7F and H). Of note, IL‐4, IL‐6, and IL‐17 were undetectable after CTL restimulation (data not shown).

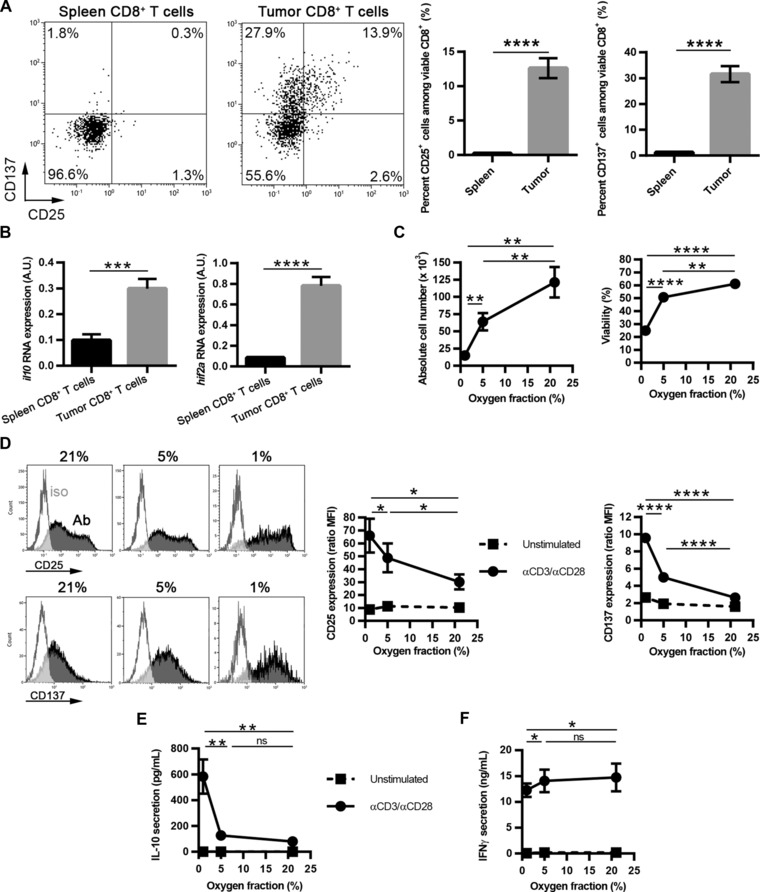

As IL‐10, CD25, and CD137 were strongly upregulated in reactivated CTLs by hypoxia in vitro, we confirmed these results in vivo and ex vivo using the E.G7‐OVA tumor model. To show that CD8+ tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) indeed express CD25, CD137, and IL‐10 in vivo, we purified CD8+ TILs and compared them to CD8+ T cells from spleen. Whereas in the spleen, CD25 and CD137 were not expressed, ∼13% of CD8+ TILs were CD25+ and ∼30% were CD137+ (Fig. 4A), with most CD25+ cells coexpressing CD137. As IL‐10 protein cannot be observed easily without in vitro cell manipulation, we looked at il10 RNA. Expression was higher in CD8+ TILs as compared to CD8+ splenocytes (Fig. 4B); moreover, hif2a was also overexpressed. As indicated by scatter graphs showing correlation between CD8+ purity and il10 mRNA (Supporting Information Fig. 8C), il10 mRNA expression was not from contaminating non‐T cells such as tumor cells or macrophages. In order to confirm that oxygen fraction is a major regulator of CD8+ TIL expansion, and of CD25, CD137, and IL‐10 expression, we reactivated CD8+ TILs ex vivo with anti‐CD3/anti‐CD28‐coated beads under varying oxygen fractions (i.e. 21, 5, and 1%). As we previously described using in vitro generated CTLs, expansion, and viability correlated positively with oxygen levels (Fig. 4C). Finally, confirming our in vitro data, we observed that CD25, CD137 (Fig. 4D), and most importantly IL‐10, were negatively correlated with oxygen levels (Fig. 4E). Importantly, upregulation of these molecules under hypoxia needed a combination of TCR‐ligation plus hypoxia (Fig. 4D, E). In addition, IFN‐γ secretion was slightly decreased under hypoxia (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

CD25, CD137, and IL‐10 are expressed by CD8+ TILs ex vivo, and are positively regulated by hypoxia after reactivation. Spleen and tumor CD8+ T cells were purified from E.G7‐OVA‐bearing mice. (A) CD25 and CD137 expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. Dot plots show one representative experiment. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM percent CD25‐positive or CD137‐positive CD8+ T cells from six independent experiments (n = 17). (B) il10 and hif2a expression were quantified by qPCR. Results show mean + SEM expression from five independent experiments (n = 13). (C–F) CD8+ TILs were cultured for three days with or without αCD3/αCD28‐coated beads. (C) Results show mean ± SEM absolute cell number and viability from four independent experiments (n = 8). (D) CD25 and CD137 were analyzed by flow cytometry. Open histograms: control isotype staining; closed histograms: staining for the molecule of interest. Line graphs (dashed lines: unstimulated; solid lines: αCD3/αCD28‐stimulated): median fluorescence intensity ± SEM from four independent experiments (n = 8). (E) IL‐10 and (F) IFN‐γ secretion were quantified by ELISA. Results show mean ± SEM cytokine secretion from four independent experiments (n = 8). ns: not statistically significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001 (Student's t‐test).

Discussion

Understanding the impact of hypoxia on CD8+ T‐cell responses represents an important step to predict in vivo immune function, notably in cancer and infection. Indeed, when developing immunotherapies based on T cells (e.g. vaccines, adoptive cell transfer), the effector cells will have to function in a hypoxic environment.

A central issue in judging the impact of hypoxia is choosing the appropriate physiologic oxygen reference point. Previous work on T cells 18 convincingly demonstrated that physioxia considered as 2% O2 56, or as 5% O2 19 significantly impacts naïve T‐cell activation, as compared to AtO2. Therefore it is unsurprising that there is little consensus on the effects of hypoxia and low oxygen tensions on T cells when most other studies chose to compare responses under hypoxia with AtO2 (that could be considered as hyperoxia) 27, 29, 33, 34, 35. Our study rationale was designed to allow a more comprehensive appreciation of hypoxia impact, by comparison with both AtO2 and physioxia (5% O2).

We observed that CTLs generated under physioxia had a predominantly effector rather than memory phenotype and had increased GrB content. Furthermore, Blimp1, a transcription factor associated with effector differentiation 57 was upregulated, while Tcf7, a transcription factor associated with differentiation and persistence of memory CD8+ T cells 58 was downregulated. Consistent with the effector versus memory profiling, CTLs generated under physioxia were more lytic than those generated at 21% O2, suggesting that CTL generation under AtO2 (e.g. for adoptive therapy) could be suboptimal. This is consistent with previous reported increased granzyme A expression and cytotoxicity of T cells preactivated under physiologic oxygen tensions 18, 59. This might also be linked to increased HIF activity under physioxia, as HIFs were described to increase CTL effector function 17, 41. Our results show that physioxia (as found in secondary lymphoid organs) facilitates efficacious CD8+ T‐cell expansion and differentiation, and that in vitro analyses under AtO2 poorly mimic these in vivo conditions. Of particular interest, eight important genes described to be hypoxia‐regulated, including the widely reported Vegfa and Glut1 genes, were regulated even under the physiologic oxygen value that we chose as physioxia (i.e. 5%), as compared to AtO2. The impact of oxygen tensions is relevant to understand T‐cell priming under physioxia 18, 19, even if naïve T cells only rarely enter hypoxic sites as in the tumor bed 60, 61. Naïve and effector T cells will be expected to differ in their sensitivity to activation stimuli since they are phenotypically distinct, and possess unique metabolic patterns (e.g. glucose and cysteine requirements) 17, 62.

For effector CD8+ T‐cells, their reactivation will frequently occur in poorly oxygenated, and often hypoxic tissues, at a lower oxygen fraction than during priming. However, the critical issues of their survival, expansion, and function under such in vivo relevant conditions were seldom addressed 17, 41. In agreement with previous studies 38, 40, we observed that hypoxia did not modify CTL killing capacities in a short‐term assay, regardless of the oxygen tension used for CTL generation. Nevertheless, we noticed that preconditioning for three days under hypoxia of CTLs generated under AtO2 increased their lytic capacities. Importantly, we showed that CTL expansion following reactivation was strongly decreased under hypoxia, with both decreased viability and proliferation. We hypothesized that the underlying defect may be linked to disturbed IL‐2R signaling, as recently shown in CD4+ T cells 30, but addition of exogenous IL‐2 to CD8+ TILs did not restore proliferation under hypoxia (Supporting Information Fig. 8D), despite elevated expression of CD25. Another explanation could be hypoxia‐induced immune regulation through adenosine‐A2AR signaling 46, 63. However, our results (with reactivated CD8+ T cells) are more in line with a recent publication showing a hypoxia‐induced A2AR‐independent decrease of cell expansion 42, since we observed neither CD25, nor Fasl downregulation that characterizes adenosinergic‐induced immunosuppression 63, 64. However, in an in vivo microenvironment where adenosine levels have been shown to be high, hypoxia‐induced adenosinergic–dependent and independent inhibition of T‐cell expansion might occur concomitantly.

As expected, hypoxia during CTL reactivation led to strong modulation of numerous genes (21 genes upregulated and four genes downregulated, of 42 tested) when comparing hypoxia to AtO2. However, as compared to physioxia, hypoxia was much less potent, modulating expression of only five of the 42 genes. Nevertheless, all of these genes overlapped with those identified as being modulated following switching cells from atmospheric to hypoxic conditions. Among these, two of the upregulated genes that we confirmed to be overexpressed at the protein level, tnfsrf9 (CD137) and il2ra (CD25), were previously reported to be hypoxia‐regulated 18, 30, 44. Of particular interest, from the whole panel of genes analyzed, il10 was the most highly modulated gene by CTLs under hypoxia. We propose that identifying hypoxia impact relative to physioxia rather than AtO2 is the best approach to identify truly hypoxia regulated gene expression that should be prioritized to further investigate for their in vivo significance in hypoxic tissues.

Concerning cytokine secretion, CTLs secreted less IFN‐γ, TNF‐α, and IL‐2 under hypoxia; this might be a consequence of decreased CTL expansion under hypoxia. However, despite this (but consistent with RNA expression) CTLs and CD8+ TILs secreted increased amounts of the IL‐10 immunomodulatory cytokine after restimulation under both physioxia and hypoxia, with hypoxia being the most potent inducer. This was only observed for effector CD8+ T cells, as the priming of naïve CD8+ T cells under hypoxia did not lead to IL‐10 secretion (data not shown). Since we observed negligible secretion of IL‐10 by CTLs reactivated under AtO2, our results suggest that this capacity of CTLs is underestimated by conventional in vitro methodology, but will likely occur in vivo in many tissues, as we observed for il10‐expressing CD8+ TILs. In the limited number of reports concerning IL‐10 production by CD8+ T cells that we are aware of, most have been in the context of infection: coronavirus‐induced acute encephalitis, chronic mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, and respiratory viral infection 65, 66, 67, 68. CTL‐produced IL‐10 has been suggested as a feedback mechanism to dampen immunopathology caused by excessive cytolytic and inflammatory activity 69. Our results support such a function, since hypoxia is a feature of infected tissues 7. However, although IL‐10 is mainly known for its immunosuppressive activity, some studies have shown immunostimulatory effects 70. We did not observe any stimulatory or inhibitory effects of IL‐10 on CTL‐expansion under hypoxia, but in a complex in vivo microenvironment, it could act in a paracrine manner on other immune cells, or on tumor cells. In malignancy, the role of IL‐10 is still a matter of debate, with promotion of tumor immune surveillance being reported 71, but also correlation with poor prognosis, increased cancer recurrence, and metastasis 72. It will be critical to determine in future studies whether IL‐10 produced by tumor‐specific CTLs can impact on their therapeutic efficacy.

Our study sheds light on specific effects of low oxygen tensions and hypoxia on the function and fate of effector CD8+ T cells in an in vitro model of tissue oxygenation. The use of monoclonal CD8+ T cells with identical sensitivity to ligands precluded the potential drawback of selection of certain clones within polyclonal T cells because of increased fitness or affinity at a given oxygen tension. Nevertheless, our major findings were similar in polyclonal C57BL/6‐derived CD8+ CTLs and CD8+ TILs. Our data challenges the use of AtO2 as normoxia in order to determine the in vivo impact of hypoxia in vitro. Overall, we show that even if hypoxia does not disturb lytic capacities of CTLs, it could diminish antitumor or antiviral responses in vivo through a negative impact on CD8+ T cell fate and the induction of IL‐10 secretion that could act in a paracrine manner on other immune cell types or tissues. If IL‐10 released by CTLs is dampening inflammatory responses in hypoxic tissues in vivo, this may be a valuable feedback mechanism to limit immunopathology in infection, but it is likely to blunt tumor immunosurveillance or immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Mice

Pmel‐1 mice (Jackson Laboratory) carry a TCR transgene specific for human SILV (hgp100) cross‐reactive with mouse gp100 (mgp100). OT‐I mice (Charles River) carry a TCR transgene specific for ovalbumin. E.G7‐OVA tumors were induced by subcutaneous injection of 3.105 cells. Animal use was in accordance to Swiss federal law on animal protection (permission numbers: 1064/3717/2, GE/68/14, GE/80/14, GE/13/15).

Cell lines

The EL‐4 and E.G7‐OVA thymoma cell lines (ATCC) were grown in DMEM medium containing 4.5 g/L glucose, sodium pyruvate, and Glutamax (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin.

Leukocyte isolation for CTL generation

Leukocytes were extracted from spleen and lymph nodes from Pmel‐1, OT‐I, or C57BL/6 mice. Pmel‐1 and OT‐1 CD8+ T cells were primed with 10 nM hgp100 or 10 nM of OVA257–264, respectively. For polyclonal CTL generation from C57BL/6, CD8+ T cells were negatively selected using the Miltenyi CD8+ T‐cell isolation kit II (>94% purity), and were primed in a plate coated with 10 μg/mL of CD3 and CD28. Cells were cultured at 21% or at 5% oxygen, in DMEM medium containing 4.5 g/L glucose, sodium pyruvate, and Glutamax, supplemented with 6% fetal bovine serum, HEPES buffer, arginine, asparagine, penicillin, streptomycin, and 20 μM β‐mercaptoethanol. Cells were split every two days with 50 IU/mL of human recombinant IL‐2. The resulting CTLs were used 6–8 days postactivation.

Isolation of CD8+ TILs

E.G7‐OVA tumors reaching 0.5 cm were harvested and processed to extract TILs. Briefly, tumors were digested by collagenase D, leukocytes were isolated by Ficoll, then CD8‐purified using the Miltenyi CD8a (Ly‐2) kit (Supporting Information Fig. 8A, B).

CTL reactivation

CTLs were labeled with 10 μM CFSE (Invitrogen) to track cell proliferation. 105 CTLs or 5.104 CD8+ TILs were reactivated with anti‐CD3 plus anti‐CD28‐coated beads (Dynabeads, Invitrogen) at a 1:1 (cell‐to‐bead) ratio under 21, 5, or 1% O2. TIL reactivation was performed in the presence of 100 IU/mL IL‐2. One‐four days postreactivation, supernatants were collected for cytokine assessment. For IL‐10 blocking, 10 μg/mL anti‐IL‐10 antibody (clone JES5‐2A5; Biolegend) or corresponding isotype was added to the culture.

Staining for flow cytometry

For all experiments, viable cells were identified using “live/dead yellow” marker (Invitrogen) (Supporting Information Fig. 1C). For surface marker expression, cells were stained with CD8α‐FITC, ‐PECy7, ‐APC, or –APCCy7 (clone 53‐6.7; Biolegend), CD127‐PECy7 (clone A7R34; eBioscience), CD44‐AF647 (clone IM7; BD Pharmingen), CD62L‐PE (clone Mel‐14; Biolegend), CD137‐APC (clone 17B5; eBioscience), CD25‐PECy7 (clone PC61; Biolegend), GrB‐PECy5.5 (clone GB11; Invitrogen), or Bcl‐2‐AF647 (clone BCL/10C4; Biolegend) antibodies, or appropriate isotype controls. For intracellular cytokine staining, CTLs were activated for 2–3 days with anti‐CD3 plus anti‐CD28‐coated beads and were incubated overnight with GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Resulting cells were stained for CD8α, followed by intracellular staining (Fix/Perm kit; BD Biosciences) for IFN‐γ‐PECy7 (clone XMG1.2; Biolegend) and IL10‐APC (clone JES5‐16E3; Biolegend), or appropriate isotype controls. For apoptosis determination, cells were stained with AnnexinV‐APC (ImmunoTools) and propidium iodide (PI; BD Biosciences). PI‐AnnexinV+ cells were considered as apoptotic. Median fluorescence intensity (MedFI) was determined using the Gallios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and marker expression was calculated by MedFI marker/MedFI control isotype. Absolute cell numbers were determined using cell/bead number ratio normalization.

Cytotoxicity assay

EL‐4 cells were pulsed for 1 h with different concentrations of hgp100 and labeled with 2.5 μM CFSE for subsequent EL‐4 discrimination. Resulting cells were cocultured with CTLs at 21, 5, or 1% of O2 for 4 h. Two assays were performed: either by coculture with the CTLs directly obtained 6 days after priming, or by coculture with CTLs that were beforehand preconditioned 3 days at 21, 5, or 1% O2 EL‐4 cell death was quantified by flow cytometry with the "live/dead fixable yellow dead cell stain kit." CTL killing was calculated as follows: % specific lysis = (% CTL‐induced cell death—% spontaneous cell death)/(100—% spontaneous cell death).

Cell culture under specific oxygen fractions

Cells cultured at 21% O2 were placed in a classical incubator under AtO2 at 37°C and 8% CO2. For CTL generation at 5% O2, cells were incubated in a Ruskinn In Vivo2 300 Workstation at 37°C, 5% O2 and 8% CO2. All cellular manipulations were carried out under these conditions to prevent any reoxygenation of the cells. Hypoxic chambers (Billups‐Rothenberg, Inc.) flushed with gas mixtures composed of 87% N2/8% CO2/5% O2, or 91% N2/8% CO2/1% O2 were used for culture of CTLs reactivated under 5% O2 or 1% O2, respectively. All culture medium and buffers for cell manipulation were preequilibrated overnight at 4°C in gas concentrations corresponding to subsequent culture/experimental conditions.

RNA expression analyses by qPCR

RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNAeasy kit and was DNAse‐treated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amounts of RNA (53 ng) were used to synthesize cDNA (PrimerScript RT; Takara Bio Inc.) that was then assessed for il10 (forward: CCAGAGCCACATGCTCCTAGA; reverse: AGCTGGTCCTTTGTTTGAAAGAA) and hif2a (forward: TCCCAGTTCCAGGACTACGGT; reverse: GGCCACGCCTGACACCT) expressions by normalization with actb (forward: CTAAGGCCAACCGTGAAAAGAT; reverse: CACAGCCTGGATGGCTACGT) and eefa1a1 (forward: TCCACTTGGTCGCTTTGCT; reverse: CTTCTTGTCCACAGCTTTGATGA) genes through real‐time quantitative PCR (SDS 7900 HT instrument; Applied Biosystems) using the SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems). The following parameters were used: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, and 45 cycles of 95°C 15 s—60°C 1 min. Each reaction was performed in three replicates. Raw Ct values were obtained with SDS 2.2 (Applied Biosystems). The 2∆Ct method was used to normalize and linearize the results.

NanoString nCounter RNA Expression analysis

RNA from dry cell pellets was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Two hundred eighty nanogram of RNA was hybridized with multiplexed Nanostring probes and samples were processed according to published procedures 73. Probes for the analysis of 47 different genes (Nanostring technologies) included five normalization genes (Supporting Information Table 1). Background correction was done by subtracting from the raw counts the mean +2 SD of counts obtained with negative controls. Values <1 were fixed to 1. Positive controls were used as quality assessment: we checked that the ratio between the highest and the lowest positive controls average among the samples was below 3. Then, counts for target genes were normalized with the geometric mean of the three reference genes (actb, tbp, eef1a1) selected as the most stable using the geNorm algorithm 74. Counts for each RNA species were analyzed using an in house Excel macro, and then expressed as counts (molecules of RNA/sample) 75.

Cytokine secretion analysis

Cytokine content (IL‐2, IL‐4, IL‐6, IL‐10, IL‐17, IFN‐γ, and TNF) from naive and effector CD8+ T‐cell cultures was determined using the "mouse Th1/Th2/Th17 kit" cytometric bead assay or BD OptEIA sets for IFN‐γ, IL‐2, or IL‐10 (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was evaluated using the two‐tailed student's t‐test for comparison of two groups using the GraphPad Software (Prism), or a three‐way ANOVA test for RNA analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- AtO2

atmospheric oxygen fraction

- HIF

hypoxia‐inducible factor

- TIL

tumor‐infiltrating lymphocyte

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Table 1. List of the different genes and their corresponding target sequences used for RNA analysis by the Nantostring technology.

Figure 1. Normoxia, physioxia and hypoxia: experimental approach.

Figure 2. Oxygen tensions during CTL generation impact their phenotype and killing capacities.

Figure 3. Low oxygen fraction, and reactivation, promotes HIF‐1α stabilization by CTLs.

Figure 4. Oxygen tensions impact CD8+ T‐cell expansion during reactivation.

Figure 5. Time‐course of oxygen‐regulated genes in reactivated CTLs.

Figure 6. Oxygen tensions impact RNA profile of unstimulated CTLs.

Figure 7. Oxygen tensions impact phenotype and IL‐10 secretion of CTLs following reactivation.

Figure 8. IL‐2 supplementation does not reverse the hypoxia‐induced decrease of CD8+ TILs expansion following reactivation.

Phenotypic switch of CD8+ T cells reactivated under hypoxia towards IL‐10 secreting, poorly proliferative effector cells

Acknowledgments

We thank Bernard Vanhove, Denis Martinvalet, and Cristina Riccadonna for careful reading of the manuscript, and the University of Geneva “iGE3 Genomics Platform” for NanoString technology analyses. This work was supported by the “Recherche Suisse contre le Cancer” (to P.R.W. and M.D.). R.V.dS, M.D., P.R.W. designed research; R.V.dS, L.D., C.Y.M., M.D. performed research; R.V.dS, L.D., C.Y.M., M.D., P.R.W. analyzed data; and R.V.dS, P.Y.D., P.R.W. wrote the paper.

References

- 1. Ivanovic, Z. , Hypoxia or in situ normoxia: the stem cell paradigm. J. Cell Physiol. 2009. 219: 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McNamee, E. N. , Korns Johnson, D. , Homann, D. and Clambey, E. T. , Hypoxia and hypoxia‐inducible factors as regulators of T cell development, differentiation, and function. Immunol. Res. 2013. 55: 58–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carreau, A. , El Hafny‐Rahbi, B. , Matejuk, A. , Grillon, C. and Kieda, C. , Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2011. 15: 1239–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eltzschig, H. K. and Carmeliet, P. , Hypoxia and inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011. 364: 656–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tatum, J. L. , Kelloff, G. J. , Gillies, R. J. , Arbeit, J. M. , Brown, J. M. , Chao, K. S. , Chapman, J. D. et al, Hypoxia: importance in tumor biology, noninvasive measurement by imaging, and value of its measurement in the management of cancer therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2006. 82: 699–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zagzag, D. , Zhong, H. , Scalzitti, J. M. , Laughner, E. , Simons, J. W. and Semenza, G. L. , Expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1alpha in brain tumors: association with angiogenesis, invasion, and progression. Cancer 2000. 88: 2606–2618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scholz, C. C. and Taylor, C. T. , Targeting the HIF pathway in inflammation and immunity. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013. 13: 646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Palazon, A. , Aragones, J. , Morales‐Kastresana, A. , de Landazuri, M. O. and Melero, I. , Molecular pathways: hypoxia response in immune cells fighting or promoting cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012. 18: 1207–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Keith, B. , Johnson, R. S. and Simon, M. C. , HIF1alpha and HIF2alpha: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012. 12: 9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hanna, S. C. , Krishnan, B. , Bailey, S. T. , Moschos, S. J. , Kuan, P. F. , Shimamura, T. , Osborne, L. D. et al, HIF1alpha and HIF2alpha independently activate SRC to promote melanoma metastases. J. Clin. Invest. 2013. 123: 2078–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li, Z. , Bao, S. , Wu, Q. , Wang, H. , Eyler, C. , Sathornsumetee, S. , Shi, Q. et al, Hypoxia‐inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell 2009. 15: 501–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holmquist‐Mengelbier, L. , Fredlund, E. , Lofstedt, T. , Noguera, R. , Navarro, S. , Nilsson, H. , Pietras, A. et al, Recruitment of HIF‐1alpha and HIF‐2alpha to common target genes is differentially regulated in neuroblastoma: HIF‐2alpha promotes an aggressive phenotype. Cancer Cell 2006. 10: 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arsham, A. M. , Howell, J. J. and Simon, M. C. , A novel hypoxia‐inducible factor‐independent hypoxic response regulating mammalian target of rapamycin and its targets. J. Biol. Chem. 2003. 278: 29655–29660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park, E. C. , Ghose, P. , Shao, Z. , Ye, Q. , Kang, L. , Xu, X. Z. , Powell‐Coffman, J. A. et al, Hypoxia regulates glutamate receptor trafficking through an HIF‐independent mechanism. EMBO J. 2012. 31: 1379–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cummins, E. P. , Berra, E. , Comerford, K. M. , Ginouves, A. , Fitzgerald, K. T. , Seeballuck, F. , Godson, C. et al, Prolyl hydroxylase‐1 negatively regulates IkappaB kinase‐beta, giving insight into hypoxia‐induced NFkappaB activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006. 103: 18154–18159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blouin, C. C. , Page, E. L. , Soucy, G. M. and Richard, D. E. , Hypoxic gene activation by lipopolysaccharide in macrophages: implication of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1alpha. Blood 2004. 103: 1124–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Finlay, D. K. , Rosenzweig, E. , Sinclair, L. V. , Feijoo‐Carnero, C. , Hukelmann, J. L. , Rolf, J. , Panteleyev, A. A. et al, PDK1 regulation of mTOR and hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 integrate metabolism and migration of CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2012. 209: 2441–2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caldwell, C. C. , Kojima, H. , Lukashev, D. , Armstrong, J. , Farber, M. , Apasov, S. G. and Sitkovsky, M. V. , Differential effects of physiologically relevant hypoxic conditions on T lymphocyte development and effector functions. J. Immunol. 2001. 167: 6140–6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Atkuri, K. R. and Herzenberg, L. A. , Culturing at atmospheric oxygen levels impacts lymphocyte function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005. 102: 3756–3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Atkuri, K. R. , Herzenberg, L. A. , Niemi, A. K. and Cowan, T. , Importance of culturing primary lymphocytes at physiological oxygen levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007. 104: 4547–4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mendez, O. , Zavadil, J. , Esencay, M. , Lukyanov, Y. , Santovasi, D. , Wang, S. C. , Newcomb, E. W. et al, Knock down of HIF‐1alpha in glioma cells reduces migration in vitro and invasion in vivo and impairs their ability to form tumor spheres. Mol. Cancer 2010. 9: 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li, P. , Zhou, C. , Xu, L. and Xiao, H. , Hypoxia enhances stemness of cancer stem cells in glioblastoma: an in vitro study. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013. 10: 399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rebucci, M. and Michiels, C. , Molecular aspects of cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013. 85: 1219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moeller, B. J. , Cao, Y. , Li, C. Y. and Dewhirst, M. W. , Radiation activates HIF‐1 to regulate vascular radiosensitivity in tumors: role of reoxygenation, free radicals, and stress granules. Cancer Cell 2004. 5: 429–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chouaib, S. , Janji, B. , Tittarelli, A. , Eggermont, A. and Thiery, J. P. , Tumor plasticity interferes with anti‐tumor immunity. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2014. 34: 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morinet, F. , Casetti, L. , Francois, J. H. , Capron, C. and Pillet, S. , Oxygen tension level and human viral infections. Virology 2013. 444: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Makino, Y. , Nakamura, H. , Ikeda, E. , Ohnuma, K. , Yamauchi, K. , Yabe, Y. , Poellinger, L. et al, Hypoxia‐inducible factor regulates survival of antigen receptor‐driven T cells. J. Immunol. 2003. 171: 6534–6540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Krieger, J. A. , Landsiedel, J. C. and Lawrence, D. A. , Differential in vitro effects of physiological and atmospheric oxygen tension on normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation, cytokine and immunoglobulin production. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1996. 18: 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dziurla, R. , Gaber, T. , Fangradt, M. , Hahne, M. , Tripmacher, R. , Kolar, P. , Spies, C. M. et al, Effects of hypoxia and/or lack of glucose on cellular energy metabolism and cytokine production in stimulated human CD4+ T lymphocytes. Immunol. Lett. 2010. 131: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gaber, T. , Tran, C. L. , Schellmann, S. , Hahne, M. , Strehl, C. , Hoff, P. , Radbruch, A. et al, Pathophysiological hypoxia affects the redox state and IL‐2 signalling of human CD4+ T cells and concomitantly impairs survival and proliferation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013. 43: 1588–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dang, E. V. , Barbi, J. , Yang, H. Y. , Jinasena, D. , Yu, H. , Zheng, Y. , Bordman, Z. et al, Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Cell 2011. 146: 772–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clambey, E. T. , McNamee, E. N. , Westrich, J. A. , Glover, L. E. , Campbell, E. L. , Jedlicka, P. , de Zoeten, E. F. et al, Hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 alpha‐dependent induction of FoxP3 drives regulatory T‐cell abundance and function during inflammatory hypoxia of the mucosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012. 109: E2784–E2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roman, J. , Rangasamy, T. , Guo, J. , Sugunan, S. , Meednu, N. , Packirisamy, G. , Shimoda, L. A. et al, T‐cell activation under hypoxic conditions enhances IFN‐gamma secretion. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010. 42: 123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mikko, M. , Wahlstrom, J. , Grunewald, J. and Magnus Skold, C. , Hypoxia but not cigarette smoke modulates VEGF secretion from human T cells. Growth Factors 2009. 27: 352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Naldini, A. , Carraro, F. , Silvestri, S. and Bocci, V. , Hypoxia affects cytokine production and proliferative responses by human peripheral mononuclear cells. J. Cell Physiol. 1997. 173: 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gaber, T. , Schellmann, S. , Erekul, K. B. , Fangradt, M. , Tykwinska, K. , Hahne, M. , Maschmeyer, P. et al, Macrophage migration inhibitory factor counter regulates dexamethasone‐mediated suppression of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 alpha function and differentially influences human CD4+ T cell proliferation under hypoxia. J. Immunol. 2011. 186: 764–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zuckerberg, A. L. , Goldberg, L. I. and Lederman, H. M. , Effects of hypoxia on interleukin‐2 mRNA expression by T lymphocytes. Crit. Care Med. 1994. 22: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. MacDonald, H. R. and Koch, C. J. , Energy metabolism and T‐cell‐mediated cytolysis. I. Synergism between inhibitors of respiration and glycolysis. J. Exp. Med. 1977. 146: 698–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lukashev, D. , Klebanov, B. , Kojima, H. , Grinberg, A. , Ohta, A. , Berenfeld, L. , Wenger, R. H. et al, Cutting edge: hypoxia‐inducible factor 1alpha and its activation‐inducible short isoform I.1 negatively regulate functions of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 2006. 177: 4962–4965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cham, C. M. , Driessens, G. , O'Keefe, J. P. and Gajewski, T. F. , Glucose deprivation inhibits multiple key gene expression events and effector functions in CD8+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008. 38: 2438–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Doedens, A. L. , Phan, A. T. , Stradner, M. H. , Fujimoto, J. K. , Nguyen, J. V. , Yang, E. , Johnson, R. S. et al, Hypoxia‐inducible factors enhance the effector responses of CD8(+) T cells to persistent antigen. Nat. Immunol. 2013. 14: 1173–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ohta, A. , Madasu, M. , Subramanian, M. , Kini, R. , Jones, G. , Chouker, A. and Sitkovsky, M. , Hypoxia‐induced and A2A adenosine receptor‐independent T‐cell suppression is short lived and easily reversible. Int. Immunol. 2014. 26: 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Overwijk, W. W. , Theoret, M. R. , Finkelstein, S. E. , Surman, D. R. , de Jong, L. A. , Vyth‐Dreese, F. A. , Dellemijn, T. A. et al, Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self‐reactive CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2003. 198: 569–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Palazon, A. , Martinez‐Forero, I. , Teijeira, A. , Morales‐Kastresana, A. , Alfaro, C. , Sanmamed, M. F. , Perez‐Gracia, J. L. et al, The HIF‐1alpha hypoxia response in tumor‐infiltrating T lymphocytes induces functional CD137 (4‐1BB) for immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2012. 2: 608–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wiener, C. M. , Booth, G. and Semenza, G. L. , In vivo expression of mRNAs encoding hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996. 225: 485–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sitkovsky, M. V. , Lukashev, D. , Apasov, S. , Kojima, H. , Koshiba, M. , Caldwell, C. , Ohta, A. et al, Physiological control of immune response and inflammatory tissue damage by hypoxia‐inducible factors and adenosine A2A receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004. 22: 657–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Georgiev, P. , Belikoff, B. G. , Hatfield, S. , Ohta, A. , Sitkovsky, M. V. and Lukashev, D. , Genetic deletion of the HIF‐1alpha isoform I.1 in T cells enhances antibacterial immunity and improves survival in a murine peritonitis model. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013. 43: 655–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Greijer, A. E. , van der Groep, P. , Kemming, D. , Shvarts, A. , Semenza, G. L. , Meijer, G. A. , van de Wiel, M. A. et al, Up‐regulation of gene expression by hypoxia is mediated predominantly by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 (HIF‐1). J. Pathol. 2005. 206: 291–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Synnestvedt, K. , Furuta, G. T. , Comerford, K. M. , Louis, N. , Karhausen, J. , Eltzschig, H. K. , Hansen, K. R. et al, Ecto‐5’‐nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. J. Clin. Invest. 2002. 110: 993–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bruzzese, L. , Fromonot, J. , By, Y. , Durand‐Gorde, J. M. , Condo, J. , Kipson, N. , Guieu, R. et al, NF‐kappaB enhances hypoxia‐driven T‐cell immunosuppression via upregulation of adenosine A(2A) receptors. Cell Signal. 2014. 26: 1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang, Y. , Misumi, I. , Gu, A. D. , Curtis, T. A. , Su, L. , Whitmire, J. K. and Wan, Y. Y. , GATA‐3 controls the maintenance and proliferation of T cells downstream of TCR and cytokine signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2013. 14: 714–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Obar, J. J. , Molloy, M. J. , Jellison, E. R. , Stoklasek, T. A. , Zhang, W. , Usherwood, E. J. and Lefrancois, L. , CD4+ T cell regulation of CD25 expression controls development of short‐lived effector CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010. 107: 193–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weng, N. P. , Akbar, A. N. and Goronzy, J. , CD28(‐) T cells: their role in the age‐associated decline of immune function. Trends Immunol. 2009. 30: 306–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Peng, S. , Wu, H. , Mo, Y. Y. , Watabe, K. and Pauza, M. E. , c‐Maf increases apoptosis in peripheral CD8 cells by transactivating Caspase 6. Immunology 2009. 127: 267–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gattinoni, L. , Ranganathan, A. , Surman, D. R. , Palmer, D. C. , Antony, P. A. , Theoret, M. R. , Heimann, D. M. et al, CTLA‐4 dysregulation of self/tumor‐reactive CD8+ T‐cell function is CD4+ T‐cell dependent. Blood 2006. 108: 3818–3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Larbi, A. , Zelba, H. , Goldeck, D. and Pawelec, G. , Induction of HIF‐1alpha and the glycolytic pathway alters apoptotic and differentiation profiles of activated human T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010. 87: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Crotty, S. , Johnston, R. J. and Schoenberger, S. P. , Effectors and memories: Bcl‐6 and Blimp‐1 in T and B lymphocyte differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2010. 11: 114–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhou, X. , Yu, S. , Zhao, D. M. , Harty, J. T. , Badovinac, V. P. and Xue, H. H. , Differentiation and persistence of memory CD8(+) T cells depend on T cell factor 1. Immunity 2010. 33: 229‐240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Haddad, H. , Windgassen, D. , Ramsborg, C. G. , Paredes, C. J. and Papoutsakis, E. T. , Molecular understanding of oxygen‐tension and patient‐variability effects on ex vivo expanded T cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004. 87: 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brabb, T. , von Dassow, P. , Ordonez, N. , Schnabel, B. , Duke, B. and Goverman, J. , In situ tolerance within the central nervous system as a mechanism for preventing autoimmunity. J. Exp. Med. 2000. 192: 871–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thompson, E. D. , Enriquez, H. L. , Fu, Y. X. and Engelhard, V. H. , Tumor masses support naive T cell infiltration, activation, and differentiation into effectors. J. Exp. Med. 2010. 207: 1791–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Garg, S. K. , Yan, Z. , Vitvitsky, V. and Banerjee, R. , Differential dependence on cysteine from transsulfuration versus transport during T cell activation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011. 15: 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Huang, S. , Apasov, S. , Koshiba, M. and Sitkovsky, M. , Role of A2a extracellular adenosine receptor‐mediated signaling in adenosine‐mediated inhibition of T‐cell activation and expansion. Blood 1997. 90: 1600–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Koshiba, M. , Kojima, H. , Huang, S. , Apasov, S. and Sitkovsky, M. V. , Memory of extracellular adenosine A2A purinergic receptor‐mediated signaling in murine T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997. 272: 25881–25889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Trandem, K. , Zhao, J. , Fleming, E. and Perlman, S. , Highly activated cytotoxic CD8 T cells express protective IL‐10 at the peak of coronavirus‐induced encephalitis. J. Immunol. 2011. 186: 3642–3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sun, J. , Madan, R. , Karp, C. L. and Braciale, T. J. , Effector T cells control lung inflammation during acute influenza virus infection by producing IL‐10. Nat. Med. 2009. 15: 277–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Perona‐Wright, G. , Kohlmeier, J. E. , Bassity, E. , Freitas, T. C. , Mohrs, K. , Cookenham, T. , Situ, H. et al, Persistent loss of IL‐27 responsiveness in CD8+ memory T cells abrogates IL‐10 expression in a recall response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012. 109: 18535–18540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cyktor, J. C. , Carruthers, B. , Beamer, G. L. and Turner, J. , Clonal expansions of CD8+ T cells with IL‐10 secreting capacity occur during chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS One 2013. 8: e58612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang, N. and Bevan, M. J. , CD8(+) T cells: foot soldiers of the immune system. Immunity 2011. 35: 161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Moore, K. W. , de Waal Malefyt, R. , Coffman, R. L. and O'Garra, A. , Interleukin‐10 and the interleukin‐10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001. 19: 683–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mumm, J. B. , Emmerich, J. , Zhang, X. , Chan, I. , Wu, L. , Mauze, S. , Blaisdell, S. et al, IL‐10 elicits IFNgamma‐dependent tumor immune surveillance. Cancer Cell 2011. 20: 781–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sato, T. , Terai, M. , Tamura, Y. , Alexeev, V. , Mastrangelo, M. J. and Selvan, S. R. , Interleukin 10 in the tumor microenvironment: a target for anticancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Res. 2011. 51: 170–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Geiss, G. K. , Bumgarner, R. E. , Birditt, B. , Dahl, T. , Dowidar, N. , Dunaway, D. L. , Fell, H. P. et al, Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color‐coded probe pairs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008. 26: 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vandesompele, J. , De Preter, K. , Pattyn, F. , Poppe, B. , Van Roy, N. , De Paepe, A. and Speleman, F. , Accurate normalization of real‐time quantitative RT‐PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002. 3: research0034–research0034.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Beaume, M. , Hernandez, D. , Docquier, M. , Delucinge‐Vivier, C. , Descombes, P. and Francois, P. , Orientation and expression of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus small RNAs by direct multiplexed measurements using the nCounter of NanoString technology. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011. 84: 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Table 1. List of the different genes and their corresponding target sequences used for RNA analysis by the Nantostring technology.

Figure 1. Normoxia, physioxia and hypoxia: experimental approach.

Figure 2. Oxygen tensions during CTL generation impact their phenotype and killing capacities.

Figure 3. Low oxygen fraction, and reactivation, promotes HIF‐1α stabilization by CTLs.

Figure 4. Oxygen tensions impact CD8+ T‐cell expansion during reactivation.

Figure 5. Time‐course of oxygen‐regulated genes in reactivated CTLs.

Figure 6. Oxygen tensions impact RNA profile of unstimulated CTLs.

Figure 7. Oxygen tensions impact phenotype and IL‐10 secretion of CTLs following reactivation.

Figure 8. IL‐2 supplementation does not reverse the hypoxia‐induced decrease of CD8+ TILs expansion following reactivation.

Phenotypic switch of CD8+ T cells reactivated under hypoxia towards IL‐10 secreting, poorly proliferative effector cells