Abstract

This study estimated the prevalence and correlates of PTSD in Kenyan school children during a period of widespread post-election violence. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index was administered to 2482 primary and secondary school students ages 11–17 from rural and urban communities. A high proportion of school children had witnessed people being shot at, beat up or killed (46.9%) or had heard about the violent death or serious injury of a loved one (42.0%). Over one quarter (26.8%, 95% CI = 25.1% - 28.7%) met criteria for PTSD. Correlates of PTSD included living in a rural (vs urban) area (AOR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.41–2.11), attending primary (vs secondary) school (AOR = 2.25, 95% CI = 1.67–3.04) and being a girl (with girl as referent AOR = .70, 95% CI = .57–.86). We recommend training Kenyan teachers to recognize signs of emotional distress in school children and psychosocial counselors to adapt empirically-supported mental health interventions for delivery in primary and secondary school settings.

Keywords: Adolescents, Children, Kenya, Community violence, Trauma exposure, PTSD prevalence

Worldwide many children are exposed to potentially traumatizing events (PTEs), including physical and sexual abuse, domestic and community violence, and natural disasters (Nghi and McCaig 2002; Stein et al. 2003; McDonald et al. 2006; Finkelhor et al. 2009). Risk of anxiety, depression, disruptive behavior problems, suicidal ideation, and substance abuse is high among children who are exposed to such events (Dvir et al. 2014; Dube et al. 2006; Wethington et al. 2008). The emotional sequelae and cognitive deficits adversely affect academic performance (Margolin and Gordis 2000; Scott et al. 2014; Park et al. 2014). Children exposed to PTEs report significant deficits in verbal abilities, memory, and learning (De Bellis et al. 2013; Taylor et al. 2013). It has been shown that children who have been exposed to violence score lower in IQ tests and have reading deficits (Delaney-Black et al. 2002), yet mental health and academic consequences of exposure to traumatic experiences are under-recognized by teachers and health care providers (Cohen and Scheeringa 2009). Studies have shown that teachers acknowledge the existence of mental health problems of student and that teachers perceive that they have an important role to play in alleviating the mental health problems, but are limited in skills of recognition of mental disorders and their interventions (Reinke et al. 2011; Andrews et al. 2014; Kerebih et al. 2016; Alisic 2012).

Over the past 15 years, the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among children and adolescents has been estimated in surveys conducted worldwide. Studies carried out after natural disasters that affect whole communities show a wide range in the frequency of occurrence of PTSD, due in part to the type of event as well as temporal and geographic proximity to the event. The median estimate of PTSD in the community-wide traumatic exposure studies lies between 25 and 35% (Prashantham et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2012) which is higher than median estimates of 10–17% from settings in Europe and North America with no major political strife or natural disasters (Karsberg and Elklit 2012; Rasmussen et al. 2013; Copeland et al. 2007; Bödvarsdóttir and Elklit 2007). Armed conflicts expose children to experiences that can have long-lasting psychological effect; a study investigating posttraumatic stress reactions, depression, and anxiety in children during the Bosnia – Herzegovina civil war found that children exposed to high numbers of war time traumatic events had high levels of PTSD symptoms (Smith et al. 2001). Similar findings were reported in Palestinian children, where a link between exposure to war-related trauma and PTSD was found (Thabet and Vostanis 2000). The prevalence of PTSD among former child soldiers in Northern Uganda to be 33% (Klasen et al. 2010). In post-genocide Rwanda, estimates of PTSD among 8–19 year-olds ranged from 54% to 62% (Neugebauer et al. 2009).

In recent years Kenyans have witnessed several eruptions of violence involving many citizens. From late December 2007 through March 2008, Kenya experienced wide-spread political and ethnic turbulence when results of the December 27, 2007 presidential election were contested. The conflict was particularly intense in the Rift Valley where fighting was aided by crude weapons, houses of suspected enemies were burned down, household items were stolen, and major roads were blocked. The Lake Victoria town of Kisumu and informal settlements of Nairobi saw property destruction and fighting. Businesses were looted and burned, and increased sexual assaults were reported. During Kenya’s post-election period, many children and adolescents witnessed brutal fighting, lost parents/guardians/loved ones, were geographically displaced, and experienced physical harm.

Several studies were conducted to estimate the prevalence of PTSD among children and adolescents in areas affected by Kenya’s post-election violence (Njoroge et al. 2014; Atwoli et al. 2014; Karsberg and Elklit, 2012; Harder et al. 2012). As shown in Appendix Table 4, these studies were conducted in different years and geographic regions of Kenya; children of different ages were sampled and different PTSD measures were administered. In one study conducted in informal settlements in Nairobi, children’s PTSD symptoms were evaluated within the year in which post-election violence occurred in Kenya (Harder et al. 2012). None of the prior studies had large samples that were purposely selected to compare youth residing in rural and urban communities or youth attending primary and secondary schools with respect to their exposure to potentially traumatic experiences and the prevalence of PTSD.

Table 4.

Five studies conducted since 2008 that Report PTSD prevalence in Kenyan children and adolescents

| Authors/year | Year data collected | Kenya region | Urban/Rural | N | Age | Setting | PTSD instrument used | Time-frame of exposure | PTSD prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Njoroge et al. 2014 | 2013 | Eldoret Sub-County | Urban, peri-urban, and rural slum | 192 | 13–15 | Primary day schools | Child Impact of Event Scale, Revised Version | Lifetime PTE experience | 45.5% |

| Past 2-week PTSD symptoms | |||||||||

| Atwoli et al. 2014 | 2010–2012 |

Uasin Gishu County Western Kenya-Rift Valley |

Rural and Urban | 1565 | 10–18 | Street setting | Child Abuse Screening Tool for Children (ICAST-C) | Lifetime PTE experience | Street youth 28.8% |

| Households | Households 15.0% | ||||||||

| Charitable Institutions | Child PTSD Checklist | Past month PTSD symptoms | Charitable Institutions 11.5% | ||||||

| Karsberg and Elklit 2012 | 2012 | Central & Northern Kenya | Rural | 477 | 13–20 | Secondary boarding school | Harvard Trauma Question-naire | Lifetime PTE experience | 34.5% |

| -1 girls’ school | Past month PTSD symptoms | ||||||||

| −2 boys’ schools | |||||||||

| Harder et al. 2012 | 2008 | Nairobi informal settlement | Urban | 552 | 6–18 |

Non-school location 2 villages in largest informal settlement |

UCLA-RI | Lifetime PTE experience | 18.0% |

| Past month PTSD symptoms | |||||||||

| Current Study | 2008 | Kiambu West and Kasarni | Rural and Urban | 2439 | 11–17 | Primary schools (11–13 yrs) | UCLA-RI | Past year PTE experiences | 26.8% |

| Current Study | Secondary schools (14–17 yrs) | Past month PTSD symptoms |

While many PTSD studies report sex differences (Breslau and Anthony 2007; Tolin and Foa 2006), few have reported age or urban/rural differences in vulnerability to PTSD. A small body of evidence suggests that exposure to PTEs may have greater adverse mental health consequences for younger children compared to older children (Ogle et al. 2013; Maercker et al. 2004). A study of posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after Hurricane Katrina in the U.S. found younger children to be disproportionately affected (Osofsky et al. 2009).

With regard to urban/rural differences, some assume that because urbanization heightens exposure to a number of social problems, the prevalence of psychiatric disorders is higher in urban areas. In fact, a recent meta-analysis of 20 studies addressing urban/rural differences in psychiatric disorders among adults in high income countries supported this assumption for depression, anxiety disorders, and all disorders (Peen et al. 2010). In the U.S. National Comorbidity Study, adolescents residing in urban areas had higher odds of exposure to physical abuse by caregivers and trauma to a loved one, and lower odds of automobile accidents compared to adolescents in rural areas (McLaughlin et al. 2013). No studies of children and adolescents have reported urban/rural differences in PTSD prevalence. Age and urban/rural differences in PTSD prevalence are not addressed in prior Kenyan studies.

The current study was designed to assess the exposure to potentially traumatizing events and the prevalence of PTSD in Kenyan children during the time period surrounding the Kenyan presidential election of 2007. Using purposive stratified random sampling, we recruited a large number of students attending primary and secondary schools in both rural and urban areas to address the following study aims:

Estimate the proportions of Kenyan children exposed to specific types of PTEs and the prevalence of PTSD.

Compare the number and types of traumatic events experienced by children with and without PTSD.

Compare the prevalence of PTSD in children attending primary and secondary school and children living in rural and urban areas.

We hypothesized that the prevalence of PTSD would be on the lower end of prior Kenyan estimates, due to the fact that the exposure period was 12-months, instead of lifetime. We also hypothesized that the prevalence of PTSD would be higher in primary school children and among children living in urban areas compared to older children and those living in rural areas.

Method

Sample/Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study, recruiting students from four primary and four secondary public schools in urban Kasarani and rural Kiambu West.

Urban Area

Kasarani District is part of the Nairobi Metropolitan area. Residents are from diverse ethnic backgrounds, including Kikuyus and Luos, the two tribal groups most deeply involved in the conflict in areas outside the Rift Valley region. Most residents are categorized as low income and their source of livelihood varies. Many residents in the area participate in small scale trading activities, popularly known as jua kali, or in small local industries, such as making soap or candles and milling grain.

Rural Area

Kiambu West District is an agricultural area located on the eastern slope of the Rift Valley about 30 km north of Nairobi. Typical farms are 0.5–5 ha. Large scale farmers produce tea and flowers for export. The town, Limuru, has small scale industries. The population consists of families who have lived in the area for generations, as well as families who have recently moved for employment. The majority of pupils in the public day schools are Kikuyu, although children from other tribes whose parents work in the area also attend. After the 2007 elections, armed conflict was heavy in Kasarani. In Kiambu West, tension was noted in the town due to employment of members of multiple tribes on the tea plantation, but no fighting erupted. Many internally displaced individuals from the Rift Valley settled in Kiambu West as a result of the conflict.

Two public primary schools and two public secondary schools were selected randomly from Kasarani and Kiambu West districts for the current study. All students in primary years 5 to 7 and secondary years 9 to 11 who attended school on the day the assessments were conducted, had parental consent, and were willing to participate were enrolled in the study. Students in secondary year 12 and primary class 8 were preparing for national examinations and were not recruited. All classroom instruction was conducted in English.

Measures

Students were classified as to urban or rural residence according to whether they lived in Kasarani or Kiambu West.

PTEs and PTSD

We administered the English-language adolescent version of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index to assess DSM–IV criteria for PTSD (Rodriguez et al. 1999). The UCLA PTSD-RI is a widely-used instrument (Steinberg et al. 2014), has undergone rigorous psychometric testing, and has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Steinberg et al. 2004; Elhai et al. 2013). In Zambia, the UCLA PTSD-RI had good internal reliability, with Cronbach alphas >.90, and was able to discriminate between locally identified cases and non-cases (Murray et al. 2011). Higher symptom scale scores were associated with exposure to higher numbers of PTEs, reflecting good concurrent validity. In Kenya, the UCLA PTSD-RI administered to impoverished youth in an informal settlement in Nairobi was reported to have Chronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients on Criterion B (intrusion) of .73, Criterion C (avoidance/numbing), .68, and Criterion D (arousal), .66 (Harder et al. 2012). Cronbach alphas in our study were slightly higher: Criterion B, .77, Criterion C, .76, and Criterion D, .69.

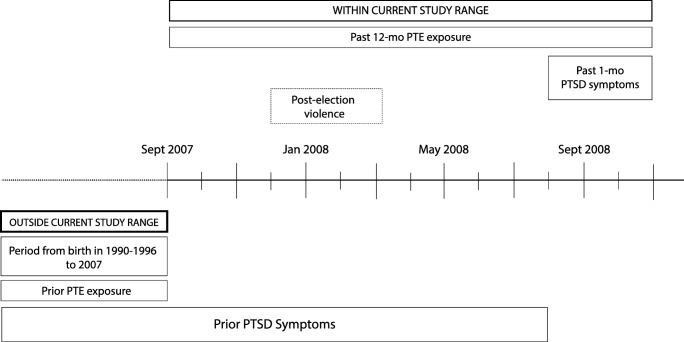

In Part I of the PTSD-RI, students were asked whether they had experienced exposure to 13 PTEs at any time over the past 12 months. Item 1 that asks about experiencing hurricanes, unknown in the study area, was removed and replaced with an item about exposure to post-election violence. Part II addresses PTSD Criteria A1 and A2. A1 evaluates aspects of the event itself, while A2 relates to the child’s subjective experience during or immediately after the event. When a child met both Criterion A1 and A2 for the identified event, s/he was classified as exposed to a PTE. Part III assesses the frequency of DSM-IV PTSD symptoms in the past 30 days using a Likert scale ranging from 0 = none to 4 = most of the time. When assigning a PTSD diagnosis, all criteria (A-D) must be met. Figure 1 shows framework for the timing of ascertainment of PTEs and symptoms in the current study.

Fig. 1.

Study timeline

Demographic Characteristics

Students also completed a demographic questionnaire in which they reported their sex, age, grade level, religion and living arrangement (two parents, one parent, guardian).

Procedures

For this study, we utilized baseline data collected for a randomized controlled trial of a school-based life skills intervention. The study was approved by the Kenyatta National Hospital and University of Nairobi Ethics Review Board and the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI). Additionally, the Ministry of Education and provincial Directors of Education in Nairobi and Central Provinces played a critical role in allowing the research team to conduct the study. Of 2700 eligible students, 2482 (91.9%) participated. We excluded 43 students with incomplete PTSD data or who were under 11 or over 17 years old. The final study sample included 2439 students with complete information. Data were collected during September and October 2008, 9–10 months after the onset of post-election violence. The principal investigator, who is a clinical psychologist, trained research assistants and visited classrooms. Research assistants read questionnaires aloud to primary school students as a classroom group. In secondary schools, research assistants distributed questionnaires and observed while students responded independently. Teachers were not present in classrooms during questionnaire administration.

Data Analysis

We estimated the prevalence of PTSD and the 95% confidence interval around the prevalence estimate. We compared characteristics of youth with and without PTSD using bivariate chi-squared tests or z-tests for categorical variables, t-test for continuous variables, and rank sum tests for count variables. With logistic regression, we estimated the increased odds of PTSD conferred by exposure to each of the different types of traumatizing events. We also evaluated the incremental effect of exposure to each additional type of PTE. Finally, we built a multivariate model to determine whether the prevalence of PTSD differed significantly by sex, age group (11–13 years vs 14–17 years) urban/rural residence, primary/secondary school enrolment, religion, and living arrangement. We added number of PTEs to a final logistic model to ascertain whether exposure to more PTEs explained why children with particular demographic characteristics were at higher risk of PTSD. All tests were two-sided; a p value < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12 (StataCorp n.d.).

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Children Sampled

The sample had an equal representation of children aged 11–13 years and 14–17 years and of females and males; 41.6% of the sample resided in the rural area; 69.1% were enrolled in primary school. For living arrangements, 64.5% of students resided with two parents, 23.4% with a single parent, and 11.3% with a guardian. The sample was predominantly Protestant Christian or Roman Catholic with a small proportion of Muslims and children endorsing “Other” religion.

Prevalence of Exposure to PTEs and PTSD

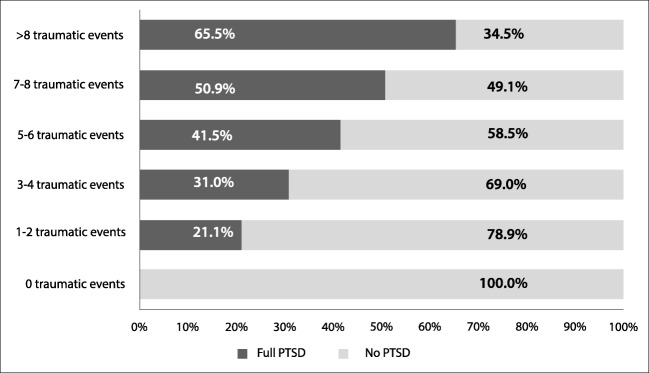

A total of 2046 (83.9%, 95% CI = 82.3%–85.5%) children reported having experienced one or more potentially traumatic events in the past 12 months (Fig. 2). The modal number of PTE’s to which children were exposed was three to four. Nearly one in five children had been exposed to seven or more different types of events. As shown in Table 1, the types of PTEs experienced by the highest proportions of youth included: seeing someone in their area beaten up, shot at or killed (46.9%), hearing about the violent death or serious injury of a loved one (42.0%), seeing someone dead (41.9%) and being in a place where fighting/war was going on around them (37.4%). The least commonly endorsed PTEs were exposure to fire, flood or other kind of natural disaster (11.7%) and being in a bad accident (9.2%). A total of 337 children (13.9%) reported having witnessed post-election violence within the past 12 months.

Fig. 2.

Number of PTEs to which Kenyan School Children were exposed

Table 1.

Exposure to PTEs in Kenyan School Children

| Potentially traumatic events | Entire sample | Full PTSD | No PTSD | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% confidence interval (CI) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Being involved in post-election violence | 337 | 13.9 | 148 | 22.6 | 189 | 10.6 | 2.46 | 1.94–3.12 | <.001 |

| Being in another kind of disaster, like a fire or flood | 285 | 11.7 | 136 | 20.8 | 149 | 8.4 | 2.87 | 2.23–3.70 | <.001 |

| Being in a bad accident, like a very serious car accident | 223 | 9.2 | 102 | 15.6 | 121 | 6.8 | 2.54 | 1.91–3.36 | <.001 |

| Being in a place where a war was going on around you | 910 | 37.4 | 334 | 51.1 | 576 | 32.4 | 2.17 | 1.81–2.61 | <.001 |

| Being hit, punched, or kicked very hard at home (not ordinary fights) | 582 | 23.9 | 237 | 36.1 | 345 | 19.4 | 2.34 | 1.92–2.86 | <.001 |

| Seeing a family member being hit, punched or kicked very hard at home | 566 | 23.3 | 224 | 34.2 | 342 | 19.2 | 2.18 | 1.79–2.67 | <.001 |

| Being beaten up, shot at or threatened to be hurt badly in your area | 412 | 17.0 | 182 | 27.8 | 230 | 13.0 | 2.58 | 2.07–3.22 | <.001 |

| Seeing someone in your area being beaten up, shot at or killed | 1139 | 46.9 | 372 | 57.1 | 767 | 43.2 | 1.76 | 1.46–2.09 | <.001 |

| Seeing a dead body in your area (do not include funerals) | 1019 | 41.9 | 335 | 51.2 | 684 | 38.5 | 1.67 | 1.39–2.00 | <.001 |

| Having an adult or someone much older touch your private sexual body parts | 244 | 10.0 | 115 | 17.6 | 129 | 7.3 | 2.72 | 2.08–3.56 | <.001 |

| Hearing about the violent death or serious injury of a loved one | 1020 | 42.0 | 354 | 54.1 | 666 | 37.5 | 1.96 | 1.64–2.36 | <.001 |

| Having painful and scary medical treatment in a hospital | 740 | 30.4 | 299 | 45.7 | 441 | 24.8 | 2.54 | 2.11–3.07 | <.001 |

Of the children, 654 (26.8%, 95% CI = 25.1%–28.7%) met full criteria for PTSD. Table 1 illustrates that the odds of exposure to each of the 13 PTEs were significantly higher (p < .001) for children with PTSD compared to children without PTSD, with odds ratios ranging from 1.67 to 2.87. Those who witnessed post-election violence were 2.49 (95% CI = 1.95–3.13) times more likely to endorse full PTSD symptoms. The median number of PTEs for children with PTSD was four, compared to a median of two PTEs for children without PTSD (z = −16.52, p < .001). As shown in Fig. 2, the prevalence of PTSD increased incrementally as the number of PTEs increased.

Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Prevalent PTSD

Table 2 illustrates differences in sociodemographic characteristics between children who did and did not meet PTSD criteria, and Table 3 shows results of multivariable analyses of associations between these characteristics and past month prevalence of PTSD. As seen in Table 2, PTSD prevalence was higher among girls, primary school children, children living in rural areas, and children living with adults other than parents. No significant differences in PTSD prevalence were found among children whose religion was Muslim, Christian (Protestant or Catholic). As shown in Table 3, the differences in PTSD prevalence in these subgroups of children were not explained by exposure to a higher number of PTEs. When differences in the number of traumatic events to which children were exposed were taken into account, living in a rural area remained a significant predictor for the occurrence of PTSD, (AOR = 1.72, 95% CI =1.41–2.11), as did being enrolled in primary school (AOR = 2.25, 95% CI = 1.67–3.04) and being a female (AOR = .70, 95% CI = .57–.86, with female as referent). Adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics, we found that, on average, exposure to each additional traumatic event doubled the odds of PTSD.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Kenyan School Children with and without PTSD

| Characteristics | Full PTSD | No PTSD | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 656 | N = 1783 | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age | |||||

| 11–13 years | 394 | 32.3 | 825 | 67.7 | <.001 |

| 14–17 years | 262 | 21.5 | 958 | 78.5 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 366 | 29.8 | 864 | 70.2 | <.001 |

| Male | 290 | 24.0 | 919 | 76.0 | |

| School | |||||

| Primary | 536 | 31.8 | 1149 | 68.2 | <.001 |

| Secondary | 120 | 15.9 | 634 | 84.1 | |

| School Location | |||||

| Rural | 309 | 30.5 | 705 | 69.5 | <.001 |

| Urban | 347 | 24.4 | 1078 | 75.7 | |

| Religion | |||||

| Catholic | 219 | 29.4 | 527 | 70.6 | .226 |

| Muslim | 22 | 25.3 | 65 | 74.7 | |

| Protestant | 380 | 26.4 | 1060 | 73.6 | |

| Other | 15 | 20.0 | 60 | 80.0 | |

| Living arrangement | |||||

| Guardian | 87 | 31.6 | 188 | 68.4 | .032 |

| Single Parent | 393 | 25.2 | 1167 | 74.8 | |

| Both Parents | 166 | 29.1 | 404 | 70.9 | |

Table 3.

Bivariate and multivariate associations between PTSD and child characteristics

| Characteristics | Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 14–17 years | REF | REF | REF | |||

| 11–13 years | 1.75 | 1.46–2.09 | 0.96 | 0.76–1.21 | 0.94 | 0.73–1.21 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | REF | REF | REF | |||

| Female | 1.34 | 1.12–1.61 | 1.33 | 1.10–1.61 | 1.43 | 1.16–1.75 |

| School | ||||||

| Secondary | REF | REF | REF | |||

| Primary | 2.46 | 1.97–3.06 | 2.29 | 1.73–3.05 | 2.25 | 1.67–3.04 |

| School Location | ||||||

| Urban | REF | REF | REF | |||

| Rural | 1.36 | 1.13–1.63 | 1.48 | 1.22–1.78 | 1.72 | 1.41–2.11 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Protestant | REF | REF | REF | |||

| Catholic | 1.17 | 0.96–1.42 | 1.12 | 0.92–1.38 | 1.07 | 0.86–1.32 |

| Muslim | 0.95 | 0.58–1.56 | 0.99 | 0.59–1.38 | 0.91 | 0.52–1.58 |

| Other | 0.70 | 0.39–1.25 | 0.78 | 0.43–1.41 | 0.82 | 0.44–1.51 |

| Living arrangement | ||||||

| Both Parents | REF | REF | REF | |||

| Guardian | 1.38 | 1.04–1.83 | 1.46 | 1.09–1.95 | 1.34 | 0.98–1.83 |

| Single Parent | 1.23 | 0.99–1.52 | 1.23 | 0.99–1.54 | 1.11 | 0.87–1.40 |

| Number of traumatic events | 1.95 | 1.79–2.12 | N/A | 1.97 | 1.80–2.15 | |

In more refined examinations of our data we determined that children living in rural areas were not more likely than children living in urban areas to report exposure to any specific type of PTE. However, younger children were significantly more likely than older children to report past 12-month exposure to natural disasters, bad accidents, being beaten up, shot at or threatened, getting hit, punched, or kicked at home, and having painful, scary medical treatment. The difference between the prevalence of PTSD in the 348 primary school girls living in rural areas (38.4%) and the 241 secondary school boys living in urban areas (13.3%) was substantial, X2(1) = 43.23, p < .0001). Exploring possible differences in specific features of PTSD, we found that nearly identical proportions of children in these two groups met Criterion A (63.2% vs 59.8%), however highly significant differences were found between the two groups in the percentage who met criteria B (73.6% vs 44.4%), C (56.0% vs 25.3%), and D (62.3% vs 33.2%), meaning that primary school girls from rural areas were about twice as likely to experience intrusion, avoidance, and arousal symptoms as secondary school boys from urban areas.

Discussion

Our study found that a high proportion of Kenyan school children had been exposed to potentially traumatizing events over the year that included three months of widespread civil conflict and ethnic strife. One in four school-aged children met DSM-IV criteria for PTSD. Systematic sampling enabled us to determine which children were at highest risk. While exposure to PTEs was high for all subgroups, female children who attended primary school, lived in rural communities, and resided with non-parent guardians suffered disproportionately from the psychological sequelae. The significantly elevated prevalence of PTSD in these children was not explained by their exposure to more PTEs.

Witnessing or hearing about a loved one being beaten, shot at, or killed, seeing a dead person (not at a funeral), and being in a place where a war was going on were the most commonly reported PTEs associated with PTSD. More than half of the PTSD-affected children endorsed each of these types of exposure. Witnessing, seeing, or hearing about someone beaten, shot, dead, or killed were also the most commonly reported exposures associated with childhood PTSD in studies conducted in India, Faroe Islands, Denmark, and Iceland (Rasmussen et al. 2013; Bödvarsdóttir and Elklit 2007; Petersen et al. 2010; Elklit 2002). These are events that children are particularly susceptible to witness in times of war.

Our results confirmed previous studies reporting an incremental increased risk of developing PTSD with exposure to more PTEs ((Harder et al. 2012; Elklit 2002; Ndetei et al. 2007; Drury et al. 2013). Many Kenyan children witness domestic violence in their households and neighborhoods and corporal punishment in their schools. According to the 2008 Kenyan Demographic and Health Survey, 24.0% of Kenyan women were exposed to domestic violence (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2008). Although corporal punishment was banned in Kenyan schools in 2001 (Kenya Gazette 2011), it is still widely practiced, particularly in rural areas (Kimani et al. 2012). Dead bodies of victims of violence are not removed from the site until after police investigation. The longer the police investigation runs, the greater the chance that children will view the dead body. Unfortunately, acts of community violence, including armed robbery and attacks in shopping centres, market places, churches, and schools are still commonly witnessed by Kenyan children.

This is the only Kenyan study of PTSD in the period of post-election violence that restricted exposure measurement to a 12-month period that included the end of December through March 2008. This is also the first Kenyan study that was designed to compare PTSD prevalence among children residing in urban and rural areas. We found that children residing in the rural area had 72% increased odds of past-month PTSD compared to children residing in the urban area. While media reported higher intensity of the post-election conflicts in the urban area, families residing in rural areas have greater challenges accessing health services for physical and emotional trauma. According to the Kenya National Human Development Report of 2009, 52% of persons living in rural areas have to travel a distance of 5 or more kilometres to reach a healthcare facility, compared with 12% in urban areas (UNDP Kenya 2009). In the rural areas, extended families live near each other, and traumatic events are more likely to be experienced collectively (Mbigi and Maree 2005). Collective experience of traumatic events may intensify children’s emotional responses.

The past-month prevalence of PTSD was also substantially higher in students enrolled in primary schools, compared to secondary school students. The highest prevalence of PTSD in the four prior Kenyan studies was reported by Njoroge et al. (2014) in which only 13–15 year old children attending primary day schools were sampled. When discussing their findings of a higher prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptoms in younger children after Hurricane Katrina, Osofsky et al. (2009) posited that this finding “may reflect the emotional immaturity of younger children, as well as their increased dependence on family and community supports,” p. 219 (Osofsky et al. 2009). The authors also suggested that older adolescents are better able to regulate their emotional responses and to rely on peers for support.

A second possible explanation for primary and secondary school differences is that the Kenyan government has established Guidance and Counselling Departments in public secondary schools but not in primary schools. This affords secondary school students opportunities to get help for their emotional problems, while primary school students may have little or no access to psychological assistance. Another possible contributor to differences in prevalence between primary and secondary schools is the selection of healthier youth into secondary school settings. Because of school drop-out, a fraction of Kenyan children who attend primary schools advance to secondary school. Symptoms of PTSD interfere with children’s ability to concentrate and learn, and young people may leave school due to the psychological sequelae of exposure to traumatic events. Additionally, strenuous academic demands can precipitate stress reactions. Thus, a healthier subset of the population selectively enters and remains in secondary school.

We evaluate our findings in light of methodological similarities and differences between our study and four prior studies of PTSD in Kenyan children conducted since 2007. Unlike the other Kenyan studies that queried about life-time exposure to PTEs, children and adolescents in our study were queried about past-year exposure. Thus, the events they reported were more likely to be related to the political strife. Excluded from the PTSD prevalence estimate in the current study were students who may have experienced recent symptoms in response to traumatizing events to which they were exposed earlier in life. A major advantage of the current study is that the 12-month exposure window was uniform for child participants of all ages, whereas in the prior studies, compared to younger children sampled, older children had accumulated more opportunity for lifetime exposure to PTEs.

Our prevalence estimate is within the range of 18% to 45.5% for estimates reported by prior Kenyan investigative teams. The study by Harder et al. (2012) was most similar methodologically to the current study in that the research team administered the same PTSD measure in a similar historical period. In the prior study, investigators reported 88% of youth with lifetime exposure to at least one PTE, higher than the upper 95% confidence limit of the prevalence estimate for past-12-month PTE exposure reported in the current study (Harder et al. 2012). In both studies, seeing somebody being beaten up, shot at, or killed was the most commonly reported PTE. Even though the PTEs were restricted to the prior year, the 1-month prevalence of PTSD was higher in the current study (26.8%) than in the Harder et al. study (18.0%) (Harder et al. 2012). Our study recruited youth from both urban and rural area schools, while the prior study recruited youth from urban households, only. The prevalence of PTSD among the urban students in our study (24.3%) was somewhat closer to the Harder et al. (2012) study overall prevalence estimate.

Our study has a number of limitations; due to limited resources, assessments were restricted to adolescent self-report. Parents and teachers may have contributed valuable perspectives on students’ emotional health. The exclusion of children who were not enrolled in school likely yielded a lower PTSD estimate than would have been found in the general population of Kenyan children, particularly at the older end of the age spectrum. Our list of PTEs did not include exposure to violence in the media. According to a 2010 census report, 80% of households in Kiambu West and Kasarani districts owned radios, and over 50% owned a television (KNBS, 2008). Kenyans often visit neighbours to watch TV news, and media reports of violent events may have contributed to children’s distress.

Despite these limitations, the study was able to advance understanding of the correlates of PTSD among Kenyan children. The study sample was large and was selected systematically to enable comparisons between primary and secondary school students and students residing in rural and urban areas. The participation rate was high. Data were collected under well-standardized conditions, and the PTSD scale had been validated in prior East African studies. PTE assessments focused on a 1-year period when eruptions of violence and geographic resettlement were occurring. Multivariable analyses were used to evaluate associations between PTSD and a set of socio-demographic characteristics.

Our study found that one in six secondary school students and nearly one in three primary school students met criteria for PTSD. Results showing the prevalence of PTSD to be highest among girls attending primary schools in rural areas who are living with non-relatives will help to raise awareness about a subgroup of children who are particularly vulnerable to the emotional health impact of traumatic experiences. Kenyan teachers should receive in-service trainings to recognize signs of distress, to learn how high arousal and intrusive thoughts interfere with students’ academic performance and to learn how to refer distressed students for support. The Kenyan educational system would also benefit by training and deploying psychosocial counselors onsite in both primary and secondary school settings to identify emotional health needs and provide support services.

Throughout the world, schools are the place where most children receive their mental health services (Fazel et al. 2014a, b). A recent review of educational outcomes associated with school behavioral health interventions in the United States showed positive effects on teacher reported classroom behavior, as well as student behavioral health and academic performance (Kase et al. 2017). Several interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in treating childhood PTSD (Cary and McMillen 2012; Ford et al. 2012; Black et al. 2012; Murray et al. 2015). Our results suggest that the time is rife to propose initiatives to educate teachers about the emotional health needs of school children and to employ school-based psychosocial counselors to adapt empirically-supported mental health interventions for delivery in school settings in Kenya.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Sharon W. Kiche, MPH, for her help with the literature review.

The design and field work for the study were self-sponsored. Statistical analyses and writing were supported through a Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) Award to the University of Nairobi from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health/Fogarty International Center, R25 MH099132.

Appendix

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation, institutional and national, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alisic Eva. Teachers' perspectives on providing support to children after trauma: A qualitative study. School Psychology Quarterly. 2012;27(1):51–59. doi: 10.1037/a0028590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews A, McCabe M, Wideman-Johnston T. Mental health issues in the schools: Are educators prepared? The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice. 2014;9(4):261–272. doi: 10.1108/JMHTEP-11-2013-0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atwoli L, Ayuku D, Hogan J, Koech J, Vreeman RC, Ayaya S, Braitstein P. Impact of domestic care environment on trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among orphans in Western Kenya. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e89937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black PJ, Woodworth M, Tremblay M, Carpenter T. A review of trauma-informed treatment for adolescents. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2012;53(3):192–203. doi: 10.1037/a0028441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bödvarsdóttir Í, Elklit A. Victimization and PTSD-like states in an Icelandic youth probability sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7(1):51. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau Naomi, Anthony James C. Gender differences in the sensitivity to posttraumatic stress disorder: An epidemiological study of urban young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(3):607–611. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary CE, McMillen JC. The data behind the dissemination: A systematic review of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for use with children and youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(4):748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Scheeringa MS. Post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis in children: Challenges and promises. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;11(1):91–99. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.1/jacohen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):577. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Woolley DP, Hooper SR. Neuropsychological findings in pediatric maltreatment: Relationship of PTSD, dissociative symptoms, and abuse/neglect indices to neurocognitive outcomes. Child Maltreatment. 2013;18(3):171–183. doi: 10.1177/1077559513497420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney-Black, V., Covington, C., Ondersma, S. J., Nordstrom-Klee, B., Templin, T., Ager, J., … Sokol, R. J. (2002). Violence exposure, trauma, and IQ and/or reading deficits among urban children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156(3), 280–285. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11876674 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Drury SS, Brett ZH, Henry C, Scheeringa M. The association of a novel haplotype in the dopamine transporter with preschool age posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2013;23(4):236–243. doi: 10.1089/cap.2012.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Miller JW, Brown DW, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38(4):444.e1–444.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvir Y, Ford JD, Hill M, Frazier JA. Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):149–161. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Layne CM, Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Briggs EC, Ostrowski SA, Pynoos RS. Psychometric properties of the UCLA PTSD reaction index. Part II: Investigating factor structure findings in a national clinic-referred youth sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(1):10–18. doi: 10.1002/jts.21755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elklit A. Victimization and PTSD in a Danish national youth probability sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(2):174–181. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel Mina, Hoagwood Kimberly, Stephan Sharon, Ford Tamsin. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):377–387. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel Mina, Patel Vikram, Thomas Saji, Tol Wietse. Mental health interventions in schools in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):388–398. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33(7):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Steinberg KL, Hawke J, Levine J, Zhang W. Randomized trial comparison of emotion regulation and relational psychotherapies for PTSD with girls involved in delinquency. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(1):27–37. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.632343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder VS, Mutiso VN, Khasakhala LI, Burke HM, Ndetei DM. Multiple traumas, postelection violence, and posttraumatic stress among impoverished Kenyan youth. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25(1):64–70. doi: 10.1002/jts.21660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsberg SH, Elklit A. Victimization and PTSD in a rural Kenyan youth sample. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2012;8(1):91–101. doi: 10.2174/1745017901208010091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase C, Hoover S, Boyd G, West KD, Dubenitz J, Trivedi PA, Peterson HJ, Stein BD. Educational outcomes associated with school behavioral health interventions: A review of the literature. Journal of School Health. 2017;87(7):554–562. doi: 10.1111/josh.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Gazette (2011). Kenya Law | Kenya Gazette: Supplement 25, legal notice 56. Republic of Kenya. Retrieved October 29, 2018, from http://kenyalaw.org/kenya_gazette/gazette/year/2011.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) (2008). Kenya demographic and health survey 2008–09 - Kenya National Bureau of statistics. Retrieved October 29, 2018, from https://www.knbs.or.ke/kenya-demographic-and-health-survey-2008-09/.

- Kerebih H, Abrha H, Frank R, Abera M. Perception of primary school teachers to school children’s mental health problems in Southwest Ethiopia. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2016;30:1. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2016-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimani N, Kara M, Ogetange TB. Teachers and pupils views on persistent use of corporal punishment in managing discipline in primary schools in Starehe division, Kenya. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2012;2:19. [Google Scholar]

- Klasen, F., Oettingen, G., Daniels, J., Post, M., Hoyer, C., & Adam, H. (2010). Posttraumatic resilience in former Ugandan child soldiers. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a120/1a4ad57f0d9d83ea241a94781f7002bc421e.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liu M, Wang L, Shi Z, Zhang Z, Zhang K, Shen J. Mental health problems among children one-year after Sichuan earthquake in China: A follow-up study. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e14706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maercker A, Michael T, Fehm L, Becker ES, Margraf J. Age of traumatisation as a predictor of post-traumatic stress disorder or major depression in young women. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 2004;184:482–487. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51(1):445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbigi, L., & Maree, J. (2005). Ubuntu : The spirit of African transformation management. Knowres Pub Retrieved from http://www.kr.co.za/Management/ubuntu-the-spirit-of-african-transformation-management.

- McDonald R, Jouriles EN, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Caetano R, Green CE. Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(1):137–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):815–830.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Bass J, Chomba E, Imasiku M, Thea D, Semrau K, et al. Validation of the UCLA child post traumatic stress disorder-reaction index in Zambia. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2011;5(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray Laura K., Skavenski Stephanie, Kane Jeremy C., Mayeya John, Dorsey Shannon, Cohen Judy A., Michalopoulos Lynn T. M., Imasiku Mwiya, Bolton Paul A. Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Among Trauma-Affected Children in Lusaka, Zambia. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(8):761. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndetei DM, Ongecha-Owuor FA, Khasakhala L, Mutiso V, Odhiambo G, Kokonya DA. Traumatic experiences of Kenyan secondary school students. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health. 2007;19(2):147–155. doi: 10.2989/17280580709486650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer R, Fisher PW, Turner JB, Yamabe S, Sarsfield JA, Stehling-Ariza T. Post-traumatic stress reactions among Rwandan children and adolescents in the early aftermath of genocide. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(4):1033–1045. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nghi, L., & McCaig, L. F. (2002). National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2000 outpatient department summary. Advance Data, (327), 1–27 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12661587. [PubMed]

- Njoroge MW, Sindabi AM, Njonge T. Exposure to post election violence and development of post traumatic stress disorder among children in Eldoret sub-county, Kenya. International Journal of Current Research. 2014;6:8798–8806. [Google Scholar]

- Ogle CM, Rubin DC, Siegler IC. The impact of the developmental timing of trauma exposure on PTSD symptoms and psychosocial functioning among older adults. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(11):2191–2200. doi: 10.1037/a0031985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky HJ, Osofsky JD, Kronenberg M, Brennan A, Hansel TC. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after hurricane Katrina: Predicting the need for mental health services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(2):212–220. doi: 10.1037/a0016179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Kim B-N, Choi N-H, Ryu J, McDermott B, Cobham V, et al. The effect of persistent posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms on executive functions in preadolescent children witnessing a single incident of death. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2014;27(3):241–252. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.853049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peen J, Schoevers RA, Beekman AT, Dekker J. The current status of urban-rural differences in psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;121(2):84–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen T, Elklit A, Olesen JG. Victimization and PTSD in a Faroese youth total-population sample. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2010;51(1):56–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddam John Prashantham, Russell Sushila, Russell Paul Swamidhas Sudhakar. The Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Children and Adolescents Affected by Tsunami Disaster in Tamil Nadu. Disaster Management & Response. 2007;5(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dmr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen DJ, Karsberg S, Karstoft K-I, Elklit A. Victimization and PTSD in an Indian youth sample from Pune City. Open Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;3:12–19. doi: 10.4236/ojepi.2013.31003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinke WM, Stormont M, Herman KC, Puri R, Goel N. Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly. 2011;26(1):1–13. doi: 10.1037/a0022714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, N., Steinberg, A.M., & Pynoos, R. S. (1999). UCLA PTSD reaction index-adolescent version. University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved from http://www.istss.org/assessing-trauma/ucla-posttraumatic-stress-disorder-reaction-index.aspx

- Scott BG, Lapré GE, Marsee MA, Weems CF. Aggressive behavior and its associations with posttraumatic stress and academic achievement following a natural disaster. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;43(1):43–50. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.807733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Perrin S, Yule W, Rabe-Hesketh S. War exposure and maternal reactions in the psychological adjustment of children from Bosnia-Hercegovina. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2001;42(3):395–404. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp (n.d.). Stata | StataCorp LLC. Retrieved November 1, 2018, from https://www.stata.com/company/

- Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka S, Rhodes HJ, Vestal KD. Prevalence of child and adolescent exposure to community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6(4):247–264. doi: 10.1023/B:CCFP.0000006292.61072.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Kim S, Ghosh C, Ostrowski SA, Gulley K, Briggs EC, Pynoos R. Psychometric properties of the UCLA PTSD reaction index: Part 1. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;26:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.21780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-traumatic stress disorder reaction index. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2014;6(2):96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LK, Lasky HL, Weist MD. Handbook of culturally responsive school mental health. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013. Adjusting intervention acuity in school mental health: Perceiving trauma through the lens of cultural competence; pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Thabet AA, Vostanis P. Post traumatic stress disorder reactions in children of war: A longitudinal study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(2):291–298. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin David F., Foa Edna B. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(6):959–992. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDP Kenya . Kenya National Human Development Report Youth and human development: Tapping the untapped resource. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Fu W, Wu J, Ma X, Sun X, Huang Y, et al. Prevalence of PTSD and depression among junior middle school students in a rural town far from the epicenter of the Wenchuan earthquake in China. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wethington HR, Hahn RA, Fuqua-Whitley DS, Sipe TA, Crosby AE, Johnson RL, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to reduce psychological harm from traumatic events among children and adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35(3):287–313. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]