Abstract

While research on the biological/genetic approach to trauma transmission has become increasingly abundant over the past 15 years, this research has been primarily limited to scientific research journals and has not yet significantly appeared in practice journals, graduate programs, clinical settings, or policy decisions. This paper aims to develop a bridge across disciplines, integrating a review of biological science literature with mental health literature to provide a multidisciplinary overview of the role of epigenetic mechanisms in the transmission of complex trauma. Such a multidisciplinary overview is important in allowing professionals across disciplines to approach their work with a more complete understanding of the way in which ecological systems shape trauma transmission and healing. While encouraging collaboration between researchers and providers across fields, this paper argues that to heal the person, one must first work to heal the environment.

Keywords: Intergenerational, Neurobiological stress susceptibility, Neurodevelopmentally-informed care, Person-in-environment, Resilience, Somatic stress, Transgenerational

“Deep, Enduring Wounds”: Child Maltreatment and Complex Trauma

According to a report by the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2017), there were 683,000 victims of child maltreatment in 2015 across the United States, including 1670 fatalities. The highest rate of child maltreatment was within children’s first year of life with a rate of 24.2 per 1000 nationally, indicating an increase from the 2005 report that 16.5 per 1000 children were maltreated in their first 3 years of life (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2007, 2017). These numbers represent a conservative estimate of child maltreatment in the United States, given that many cases go unreported. Additionally, these statistics mark a concerning prevalence and increase in the prevalence of child maltreatment when children are at their most developmentally sensitive age.

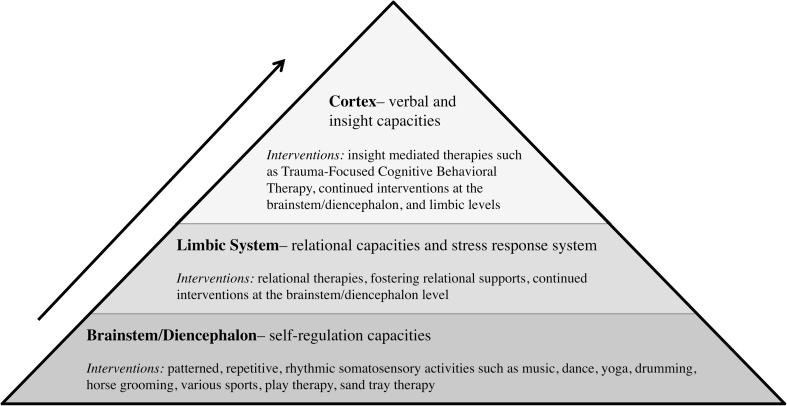

Early trauma, which has been characterized as an “environmentally induced complex developmental disorder,” (De Bellis and Zisk 2014, p. 3) has rippling effects throughout an individual’s life since it occurs when the brain is in its most critical phases of development (Buss et al. 2017; Gaskill and Perry 2017). Brain architecture is built through sequential development; the four main brain structures (brainstem, diencephalon, limbic system, and cortex) develop in a hierarchical fashion, building upon each other from the bottom up with increasing complexity (Gaskill and Perry 2017; Siegel 2015; Van der Kolk 2015). The brainstem and diencephalon are involved in self-regulation, the limbic system is involved in relational development and the body’s stress response system, and the cortex is involved in verbal abilities and insight (Perry and Szalavitz 2017; Siegel 2015; Van der Kolk 2015). Since these structures are built upon each other like a Jenga block pyramid, brain architecture remains in a precarious state if its initial structures have not been built with a firm foundation. Specifically, a safe and empathic environment is necessary during key windows of brain plasticity (Perry and Szalavitz 2017; Ryan et al. 2017; Siegel 2015).

The timing, duration, and frequency of early positive and traumatic experiences are important given the sequential and activity dependent nature of brain development (Gaskill and Perry 2017; Teicher and Samson 2016). Early experiences sculpt brain development such that, “[m]altreatment is a chisel that shapes a brain to contend with strife, but at the cost of deep, enduring wounds” (Martin Teicher, as cited in Van der Kolk 2015, p. 151). The term, “complex trauma” is used to describe the developmental ripple effects of chronic child maltreatment including “complex self regulatory and relational impairments” across domains of “attachment, biology, affect regulation, dissociation, behavioral control, cognition, and self concept” (Cook et al. 2005, p. 392). It is important not to pathologize children for developmental impacts experienced as a result of complex trauma and for the ways their bodies are attempting to adapt to harsh environments. A child with a hypervigilant stress response system may have a body primed for adaptive function within a home environment in which maltreatment is occurring; yet while at school, this same child may have difficulty focusing on learning (Ludy-Dobson and Perry 2010; Perry 2016). Constantly operating within survival mode is not sustainable for the body—bodies primed to adaptively survive in stressed environments are simply surviving and not thriving.

A Persistent Cycle

Trauma has been shown to be transmitted between and across families for up to four generations (Brendtro and Mitchell 2013). Four major theoretical approaches to understanding trauma transmission include psychodynamic/relational models, social/cultural models, family systems/communication models, and biological/genetic models (Kellermann 2013). These theoretical approaches are different ways of zooming in or out on the ecological systems in which a person has been shaped by trauma in order to develop ideas about how these systems contribute to trauma transmission. Collaborative research, teaching, and practice across theoretical domains are vital given that ecological systems at all levels are intricately intertwined and come together to shape trauma transmission in an inextricable manner.

While research in the biological/genetic approach to trauma transmission has become increasingly abundant in the past 15 years (most notably flourishing after Meaney 2001), this research has been primarily limited to scientific research journals and has not yet significantly appeared in practice journals, graduate programs, clinical settings, or policy decisions. This paper aims to develop a bridge across disciplines, integrating a review of biological science and mental health literature to provide a multidisciplinary overview of the role of epigenetic mechanisms in the transmission of complex trauma. Such a multidisciplinary overview is important in allowing professionals across disciplines to approach their work with a more complete understanding of the way in which ecological systems shape trauma transmission and healing. Additionally, this overview is meant to encourage collaboration between researchers and providers across fields in supporting resiliency for individuals impacted by complex trauma.

“Molecular Scars”

“Once again, the body keeps score, at the deepest levels of the organism” (Van der Kolk 2015, p. 154)

The biological/genetic approach to trauma transmission examines how traumatic environments shape bodies at the molecular level, leaving “molecular scars” that affect a person’s functioning and may be transmitted between and across generations (Hurley 2015). The term “epigenetics,” first introduced by embryologist Conrad Waddington in the 1940s, describes research on how environments shape bodies at the molecular level (Isles 2015; Jablonka 2016). Waddington was interested in cell differentiation and maintenance of cellular identity—how cells are able to specialize to serve many different purposes such as being a part of heart tissue or brain tissue despite all cells containing the same DNA (Isles 2015; van IJzendoorn et al. 2011). Since the DNA sequence remains constant, Waddington argued there must be some mechanism “over and above” DNA allowing cells to differentiate and maintain their specialized identity (Isles 2015, p. 65). Waddington termed this mechanism that modulates phenotype without changing genetic sequence “epigenetics” because “Greek epi = ‘above’ the genome” (van IJzendoorn et al. 2011, p. 305). A general definition of epigenetics is “…the study of biochemical modifications of the DNA influencing gene expression without altering the structural base-pair sequence itself” (van IJzendoorn et al. 2011, p. 305).

Epigenetics describes a mechanism through which DNA expression can adapt to the environment such as human cells and tissues differentiating into a four chambered heart based on what is needed for survival (Jablonka 2016). Weaver et al. (2004) was the first major study (building on previous research by Meaney 2001) demonstrating the possibility that an individual’s social as well as physical environment can shape epigenetic changes. This has led to an abundance of literature on how traumatic environments shape epigenetic processes, signaling a potential contributing mechanism for trauma transmission (Brendtro 2015; Burns et al. 2017).

Key Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Epigenetic Transmission of Trauma

The following briefly reviews the basic biology of epigenetics (See Isles 2015; Nestler 2016; and; van IJzendoorn et al. 2011; and Fig. 1). Human bodies are made up of trillions of cells. Within each cell is a nucleus which contains chromosomes. Chromosomes contain chromatin, which contain DNA wrapped around histone octomers. Each strand of the DNA double helix structure is made up of DNA bases including adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine. Adjacent cytosine and guanine bases are referred to as CpG islands. Based on environmental cues, methyl groups may attach to CpG islands, causing DNA to wrap more tightly around histones (methylation), or acetyl groups may attach to CpG islands, causing DNA to wrap more loosely around histones (acetylation). RNA polymerase unzips sections of the DNA double helix to facilitate transcription of messenger RNA (mRNA). Subsequently, DNA information is transported to the ribosomes to be turned into proteins for gene expression. Gene activity is regulated by how tightly a given DNA sequence is wrapped around histones. If a given DNA sequence has methyl groups attached to it (methylation), the DNA sequence wraps more tightly around the histone, limiting access to RNA polymerase for mRNA transcription; this results in limited gene expression (Nestler 2016). If a given DNA sequence has acetyl groups attached to it, the DNA sequence wraps more loosely around the histone, enabling access to RNA polymerase for mRNA transcription; this results in promoted gene expression (Nestler 2016).

Fig. 1.

Key molecular structures involved in epigenetics

Through epigenetics, the environment shapes DNA expression without changing the DNA sequence. There are over 20,000 coding genes within human DNA with over three million epigenetic “switches” regulating gene expression (Brendtro 2015, p. 43). One mechanism, DNA methylation/acetylation, involves methyl/acetyl groups attaching to CpG islands based on environmental cues, affecting DNA transcription without changing the DNA sequence itself. Through another mechanism, small noncoding RNA (sncRNA) may function to alter or destroy mRNA based on environmental cues before mRNA is able to carry genetic information to ribosomes for gene expression (Nestler 2016). Cortisol often regulates sncRNA, such that bodies with over-active stress response systems and excess cortisol will likely have impacted sncRNA functioning, resulting in impacted gene expression (Bowers and Yehuda 2016). Environmental shaping of methylation patterns and sncRNA behavior signal an evolutionary drive to express genes in the most adaptive manner given information available about what sort of environment the body will need to survive in (Cao-Lei et al. 2014). This environmental cueing can occur throughout the developmental cycle through germ cells (preconception), the intrauterine environment (prenatal), and the early life environment (postnatal) (Bowers and Yehuda 2016).

Modes of Epigenetic Transmission of Trauma

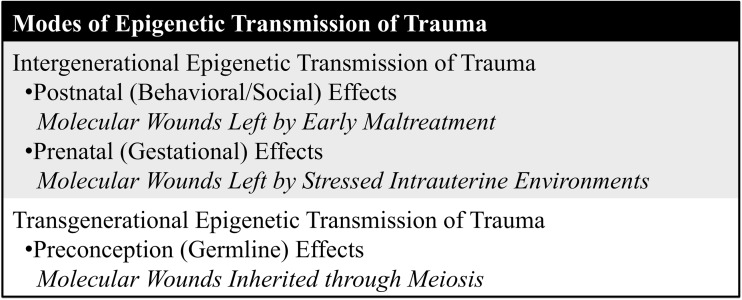

Intergenerational trauma is transmitted between two generations, including postnatal (behavioral/social) or prenatal (gestational) effects. Transgenerational trauma is transmitted across more than two generations, including preconception (germline) effects (Gröger et al. 2016). Modes of epigenetic trauma transmission are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Modes of epigenetic transmission of trauma

Intergenerational Epigenetic Transmission of Trauma

Postnatal (Behavioral/Social) Effects: Molecular Wounds Left by Early Maltreatment

Animal Studies

While research existed about the role of attachment and caregiving in trauma transmission through mechanisms such as social learning theory, Meaney (2001) was the first to propose the possibility that environmental alterations of the stress response system could be transmitted between generations through gene expression. Meaney’s (2001) research showed that rat pups with mothers who displayed higher levels of licking and grooming of the pups (nurturing care) tended to have more positive outcomes. In this way, “Meaney (2001) found that nurturing care turns on genes in the brain that regulate stress, making offspring social, curious, and confident. But neglect produces distressed, fearful offspring” (Brendtro 2015, p. 43). In replicating Meaney’s (2001) study, Weaver et al. (2004) found that variations in maternal care resulted in epigenetic differences. Rat pups receiving less maternal care displayed increased NR3C1 gene methylation, which is responsible for encoding the glucocorticoid receptor in the hippocampus (Weaver et al. 2004). Altered glucocorticoid receptors have rippling developmental effects on the stress response system (including cortisol circulation), metabolism, immune function, and cognitive function (De Bellis and Zisk 2014; Keating 2016). Poorly nurtured female rat pups also tended to develop lower oxytocin levels, resulting in more difficulty nurturing and caregiving the next generation (Brendto and Mitchell 2013).

Weaver et al. (2004) demonstrated that NR3C1 methylation due to poor maternal care could be reversed by cross-fostering rat pups with mother rats who demonstrated improved maternal care. This raised the possibility that epigenetic patterns can be programmed through the social/behavioral environment beyond the physical environment. Social/behavioral trauma transmission can become intergenerational through a “self sustaining loop” in which low maternal nurturance changes the neuro-physiology and epigenetics of daughter rats, who then have less nurturing capability, leading to epigenetic effects in their offspring as well (Jablonka 2016, p. 49). Postnatal epigenetic effects are intergenerational, not transgenerational, because they result in changes induced by behavioral/social conditions, looping between two generations, not across many generations (Jablonka 2016). Weaver et al. (2004) was able to reverse methylation effects through a deaceytlace inhibitor infusion into affected rat pups, raising the possibility of pharmacological epigenetic therapies to aid in blocking intergenerational looping of epigenetic traumatic stress patterns.

Numerous animal studies on the effects of maternal care and maternal separation on epigenetic mechanisms have been completed since the initial research by Meaney (2001) and Weaver et al. (2004). In a study of infant rats experiencing maternal maltreatment, Roth et al. (2009) found that both the infant rats and their future offspring displayed methylation of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene in the prefrontal cortex, providing further evidence for intergenerational epigenetic transmission of stress as described by Weaver et al. (2004). In a maternal separation rat study, sex-specific epigenetic effects were shown—when exposed to maternal separation, female rat pups displayed NR3C1 methylation while male rat pups displayed BDNF methylation (Kundakovic et al. 2013). In maternal separation studies with rhesus monkeys, methylation occurred in the white blood cells of young monkeys separated from their mothers, resulting in immune system effects and demonstrating that early traumatic exposure may have effects on peripheral cells in addition to neuronal cells (Szyf 2013; van IJzendoorn et al. 2011).

Human Studies

Human studies of postnatal epigenetic effects have several methodological issues including difficulty separating behavioral social learning versus behavior based on epigenetic changes, difficulty controlling for environmental effects of shared living environments beyond the caretaking dyad, and difficulty obtaining brain tissue to directly study epigenetic effects within neuronal cells (Bowers and Yehuda 2016). McGowan et al. (2009) completed one of the first human studies on postnatal epigenetic effects. The study used postmortem brain tissue samples from the Quebec Suicide Brain Bank and used psychological autopsies to divide the sample into individuals who completed suicide after experiencing child maltreatment and individuals who completed suicide without a known child maltreatment history. Individuals with a known child maltreatment history had increased methylation at the NR3C1 promoter, resulting in dysregulated glucocorticoid receptor transcription, an altered stress response system, and increased suicide risk (McGowan et al. 2009). Labonté et al. (2012) repeated the study, looking at genome-wide epigenetic effects and found that while the hippocampal neurons were most impacted, effects could also be seen across the genome.

Given increasing research that epigenetic effects may not be limited to neuronal cells, researchers have begun to use peripheral blood to study epigenetic effects within living humans. One study used blood samples of living humans to show that adults with a self-reported history of childhood adversity had higher methylation levels at the NR3C1 promoter, resulting in glucocorticoid receptor effects (Tyrka et al. 2012). Another study used blood samples of living humans to demonstrate a link between NR3C1 promoter methylation levels and reported child maltreatment type and severity (Perroud et al. 2011).

Prenatal (Gestational) Effects: Molecular Wounds Left by Stressed Intrauterine Environments

Though it is accepted that chemicals ingested by pregnant mothers affect fetal development through the intrauterine environment (as with fetal alcohol syndrome), recent research suggests social experiences of pregnant mothers also shape fetal development (Bowers and Yehuda 2016; Gröger et al. 2016). Through the intrauterine environment, maternal traumatic stress is correlated to changes in neuroendocrine, epigenetic, and neuroanatomical development.

Neuroendocrine

Placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11β-HSD2) regulates fetal exposure to cortisol so that in typical development, fetuses are only exposed to 10 – 20% of maternal cortisol circulating in the intrauterine environment (Bowers and Yehuda 2016). Studies show increased 11β-HSD2 methylation for Holocaust survivors, suggesting exposure to traumatic stress results in lower 11β-HSD2 levels (Bowers and Yehuda 2016). This epigenetic effect is translated into fetal neuroendocrine effects. Since mothers with experiences of traumatic stress may have lower 11β-HSD2 levels, there may be less regulation of cortisol exposure within the intrauterine environment, resulting in a fetal priming of stress induced activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) stress response axis (Bowers and Yehuda 2016).

Epigenetic and Neuroanatomical

Several epigenetic changes are correlated with prenatal maternal traumatic stress including methylation of the NR3C1 promoter (cortisol effects), the SLC6A4 promoter (serotonin effects), and white blood cells (immune function effects) (Bowers and Yehuda 2016; Cao-Lei et al. 2014). Increased intrauterine methylation of the NR3C1 promoter results in altered glucocorticoid receptors, leading to structural brain changes including changes in limbic structure and cortical thickness (Bowers and Yehuda 2016). Fetal synthetic glucocorticoid exposure (given to mothers at risk of preterm delivery to aid with fetal respiratory issues) creates similar anatomical changes as those induced by NRC31 methylation, suggesting that intrauterine glucocorticoid exposure may be a mediating factor between maternal traumatic stress and fetal neuroanatomical changes (Bowers and Yehuda 2016).

Transgenerational Epigenetic Transmission of Trauma

Preconception (Germline) Effects: Molecular Wounds Inherited Through Meiosis

Transgenerational epigenetic transmission of trauma involves epigenetic changes that occur before conception and are transmitted through meiosis across more than two generations (Bowers and Yehuda 2016). Research on transgenerational epigenetic transmission of trauma is still in its nascent phase and presents several methodological challenges including how to control for various other environmental transmission mechanisms such as behavioral transmission. Current research of transgenerational effects remains limited to animal studies. Most rodent studies focus on male germlines in order to better control for behavioral/caretaking transmission since male rodents are not involved in caretaking (Gröger et al. 2016; Nestler 2016).

Franklin et al. (2010) showed that DNA methylation in rat pups due to maternal separation was preserved in the offspring of the separated male pups. In a similar rat study, male offspring exposed to unpredictable maternal separation/stress were bred with stress-naïve female rats, resulting in epigenetic effects over two subsequent generations (Mansny as cited in Gröger et al. 2016). While the study tried to control for behavioral transmission through the fact that the traumatized male rats would not be raising their offspring, the stress-naïve mothers may have treated their children differently based on instinctual knowledge that they had mated with male rats who had been exposed to traumatic stress (Hurley 2015). Studies with in vitro fertilization attempt to control for this methodological challenge. In an in vitro fertilization study, discussed in Nestler (2016), female rats had sex with vasectomized rats who had not experienced chronic traumatic stress; the female rats were then injected with sperm from male rats who had experienced chronic traumatic stress. The study suggested transgenerational effects even while controlling for the stress-naïve maternal rat’s opinion of the paternal rat (Nestler 2016). Another study used in vitro fertilization to inject sperm RNA of traumatized male rats into wild type oocytes and found that offspring was effected possibly through epigenetic mechanisms of small noncoding RNA and the sensitivity that sncRNA has to the environment (Gapp et al. 2014).

A Fuller Picture of Cycles of Complex Trauma: the Role of Epigenetic Research

“Being reared in a safe and supportive environment activates genes to build resilient brain pathways. But when safety and growth needs of children are not met, the brain is redesigned for defensive survival reactions…By nature, children have resilient brains and flourish in supportive environments. But if exposed to experiences outside of the expected range, epigenetic development goes awry and causes a host of problems” (Brendtro and Mitchell 2013, p. 6).

Epigenetic trauma transmission research suggests various mechanisms through which molecular changes occur within the body to allow for adaptation to stressed environments. Exposure to traumatic stress has been shown to result in three times the effects on DNA methylation in children than in adults, melding ideas about epigenetic transmission with ideas about brain plasticity and the importance of developmental windows when children are more susceptible to environmental effects (Nugent et al. 2016). Given this, Nugent et al. (2016), has proposed “an adapted framework for the developmental traumatology model” that takes into account epigenetic influences involved in the impacted domains of complex trauma (Nugent et al. 2016, p. 58). Understanding complex trauma through a lens that includes epigenetic influences involves understanding how trauma-induced epigenetic changes may increase “neurobiological susceptibility to stress” while decreasing the ability to benefit from protective buffers that promote resilience (Kellermann 2013, p. 34).

Trauma-induced epigenetic changes can prime children for neurobiological stress susceptibility at a variety of key moments in the developmental cycle including through germ cells (preconception), the intrauterine environment (prenatal), and maltreatment in the early life environment (postnatal) (Bowers and Yehuda 2016). Environmental cues shape the body at the molecular level in an adaptive attempt to give the body what it needs to be able to survive (Gröger et al. 2016; Teicher and Samson 2016). While having a body primed to deal with stress may be adaptive in some environments such as a home in which maltreatment is occurring, it is not as adaptive in other environments such as school (Gröger et al. 2016; Ludy-Dobson and Perry 2010). This is known as the “match/mismatch hypothesis” with adaptive functioning of the body dependent on whether a particular environment matches the environment in which the adaptive functioning developed (Gröger et al. 2016, p. 8). Bodies primed through epigenetic shaping to survive in stressed environments have a neurobiological stress susceptibility and may experience “somatic chronic stress” (K. Pratt, personal communication, July 15, 2016). When these bodies are exposed to environments characterized by child maltreatment, latent epigenetic adaptations to stress may become increasingly manifest amplifying the core self-regulatory and relational issues involved in complex trauma (Kellermann 2013; Ludy-Dobson and Perry 2010).

Resilience and healing in the face of increasingly amplified self-regulatory and relational issues becomes more difficult with time as children miss developmental windows and begin to have a “less receptive relational capacity to buffer and heal” (Ludy-Dobson and Perry 2010, p. 30). In a longitudinal study on children with complex trauma, only 22% were said to demonstrate resiliency in adulthood (De Bellis and Zisk 2014).

“Deep, Enduring Wounds” and “Molecular Scars”: is Healing Possible?

“Resilience is built into human brains and is strengthened by supportive communities. Resilience is a mix of internal strengths and external supports offset by environmental risks” (Brendtro 2015, p. 45).

Good treatment first requires environments characterized by stability, safety, and social support (Geller and Porges 2014; Gaskill and Perry 2017; Rothschild 2004). Bowers and Yehuda (2016) note, “…safe, stable, nurturing relationships buffer intergenerational continuity of child maltreatment” (p. 241). Healthy relationships and empathic connections serve a key protective and healing function since positive relational interactions help to regulate the “stress response systems and the neural networks involved in bonding, attachment, social communication, and affiliation” (Perry 2009, p. 246). Brains shaped by stressed environments are characterized by survival mechanisms, whereas brains shaped by healthy relationships have greater tools to develop resiliency mechanisms (Brendtro and Mitchell 2013). Yet this does not mean that children shaped by traumatic environments miss out on any chance of resiliency and healing.

Resilience should not be seen as an “endpoint or destination” that can be missed, but rather more as “an ongoing developmental process” that can be fostered and developed to different extents through varying environmental inputs and supports (Brunzell et al. 2015, p. 8). Much like trauma, resilience can be transmitted across generations and is dependent on environmental shaping (Braga et al. 2012; Goodman 2013). An understanding of sequential brain development shows that just as there are windows of susceptibility to the developmental impacts of trauma, there are also “windows of opportunity” for developing resiliency capacities (Gröger et al. 2016; Perry 2009).

Treatment Implications: Neurodevelopmentally-Informed Care

“A 15 –year-old child may have the self-regulation capacity of a 5-year-old, the social skills of a 3-year-old, and the cognitive organization of a 10-year-old. And due to the unique genetic, epigenetic, and developmental history of each child, it is very difficult to apply a ‘one-size-fits-all’ treatment approach” (Perry and Dobson 2013, p. 250).

The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics

Supporting resiliency for individuals affected by the synergistic impacts of the “deep enduring wounds” (Teicher as cited in Van der Kolk 2015, p. 151) of child maltreatment and the “molecular scars” (Hurley 2015) of epigenetically-based neurobiological stress susceptibility requires individualized neurodevelopmentally-informed care. The “Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics” (NMT) is a global evidence-based practice model developed by ChildTrauma Academy founder, Dr. Bruce Perry, as a “developmentally sensitive, neurobiology-informed approach to clinical problem solving” (The ChildTrauma Academy 2015, p. 1; see also; Gaskill and Perry 2017; Perry 2009, 2014). Building on an understanding of sequential brain development, NMT addresses the developmental impacts of trauma through bottom up healing—targeting specific impacted brain regions in a sequential manner (Gaskill and Perry 2017).

The NMT model involves an assessment of developmental history, including relational impacts and supports, as well as an individual’s current level of functioning and a current mapping of developmental impacts (The ChildTrauma Academy 2015; Gaskill and Perry 2017; Perry 2009). Through an epigenetically-informed lens, this also includes trying to understand any potential epigenetic history involved and can be adapted to include both epigenetic mapping and resilience mapping such as the “Transgenerational Trauma and Resilience Genogram” (Goodman 2013). Such mapping is used to sequence developmentally-informed interventions that follow the bottom up brain development sequence –first addressing safety, stability, and self-regulation before moving on to address relational development, and later verbal and insight development (The ChildTrauma Academy 2015; Gaskill and Perry 2017; Perry 2009).

Applying the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics

As an evidence-based practice model, NMT was developed, not to replace other treatment approaches, but as a lens to aid in selecting and sequencing evidence-based treatments to best fit each individual’s developmental needs (Brandt et al. 2012). In an interview, Dr. Perry notes, “A cognitively focused therapeutic approach would be appropriate with a well-organized, cognitively mature youth traumatized by a school shooting but a waste of time for a severely maltreated, nonverbal, profoundly dysregulated 5-year-old” (MacKinnon 2012, p. 217). Selecting interventions in a neurosequential manner involves following the developmental sequence of “regulate, relate, reason,” while understanding that “maltreated children are not immediately ready for verbally mediated insight therapies” (Gaskill and Perry 2017, p. 60).

Individual Interventions

The NMT approach recognizes the relationship between healthy development and sequential mastery of functions such that “a dysregulated individual will be inefficient in mastering any task that requires relational abilities (limbic) and will have a difficult time engaging in more verbal/insight oriented (cortical) therapeutic and educational efforts” (The ChildTrauma Academy 2015, p. 2). See Fig. 3 for intervention mapping through the NMT lens. Targeting treatment at the brainstem/diencephalon level includes patterned, repetitive, rhythmic somatosensory interventions such as music, dance, yoga, drumming, grooming a horse, various sports, play therapy, sand tray, and art therapy as well as routines, rituals, soothing, and calming (The ChildTrauma Academy 2015; Gaskill and Perry 2017). The rhythmic nature of somatosensory interventions is important given the powerful safety associations that the brainstem and diencephalon develop in relation to the maternal heart rate in utero (MacKinnon 2012). Targeting treatment at the limbic level includes more relational therapies (The ChildTrauma Academy 2015; Gaskill and Perry 2017). Targeting treatment at the cortical level includes more insight-based therapies including talk therapy or evidence-based trauma treatment such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (The ChildTrauma Academy 2015).

Fig. 3.

Neurodevelopmentally-informed treatment: Mapping interventions through the lens of Perry’s Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics

Program Interventions

Barfield et al. (2012) demonstrated that employing predictable, repetitive, somatosensory NMT techniques in a therapeutic preschool setting resulted in decreased symptoms of impulsivity and aggression. De Nooyer and Lingard (2017) applied NMT principles to stratify group interventions at an adolescent day program and inpatient unit based on which brain areas treatment was being targeted towards rather than grouping individuals based on categorical diagnosis. For instance, one group included somatosensory activities while another focused more on relational connections and emotions (de Nooyer and Lingard 2017).

Caregiving Interventions

The Neurosequential Model of Caregiving (NMC) uses NMT to inform caregiving (DeGregorio 2013). Interventions include helping caregivers set expectations according to children’s developmental rather than chronological age and providing neurodevelopmentally-appropriate caregiving support that considers potential developmental impacts within a caregiver’s developmental history (DeGregorio 2013; Gaskill and Perry 2017).

Case Illustrations

The following composite case illustrations demonstrate the role of neurodevelopmentally-informed care in shifting treatment outcomes. The shaping effects of ecological factors such as school funding are also demonstrated, pointing to the importance of addressing neurodevelopmental considerations across professional disciplines including policy.

Discipline-Oriented, Underfunded School

Nine-year-old, “Kate” sat crouched in her classroom coat cubby, peering at her teacher between hanging pieces of fabric. The teacher’s face reddened as she raised her voice saying, “Kate, you come out of there right this instant! You’ve disrupted this class for the last time!” Kate inched her way further into the cubby. Kate’s teacher couldn’t spend any more time away from the 30 students waiting for her. She called the front office, Kate’s caregivers were called and she was sent home with a 2-week suspension.

Neurodevelopmentally-Informed, Well-Funded School

Nine-year-old, “Kate” sat crouched in her classroom coat cubby, peering at her teacher between hanging pieces of fabric. While a co-teacher continued working with the other students, Kate’s teacher sat on the floor near Kate and asked if she would be willing to take some deep breaths with her. After spending some time breathing, Kate’s teacher offered her some paper and crayons. Kate colored for a while before eventually feeling ready to step out of the cubby.

Kate began meeting with the school social worker. Applying NMT principles, the school social worker performed a detailed assessment of Kate’s developmental and epigenetic history. Given Kate’s significant child maltreatment history and epigenetic stress susceptibility, as well as suboptimal functioning across developmental domains, Kate’s social worker determined that interventions should be targeted towards the brainstem/diencephalon level of development with somatosensory interventions. The social worker met with Kate routinely to engage in somatosensory interventions. In particular, Kate enjoyed running laps around the playground as a means of rhythmic regulation. Over time, as Kate displayed more regulation at the brainstem/diencephalon levels, treatment moved to begin to target social interventions at the limbic level. Social interventions resulted in Kate asking her teachers if she could develop a running club at recess. She was then able to simultaneously engage in self-regulation and parallel play as an initial step towards building social skills. Additionally, she was able to display mastery as the running club captain. Kate’s teacher noted that as these interventions proceeded, Kate’s symptoms of dysregulation in the classroom became less frequent and she was more able to engage with academic learning.

Developing Communities that Support Healing and Resilience

“Social support is a biological necessity, not an option, and this reality should be the backbone of all prevention and treatment” (Van der Kolk 2015, p. 169).

Truly helping children begin to heal from the developmental and epigenetic wounds of trauma requires attention to the ecological context in which children develop (Perry and Szalavitz 2017; Van der Kolk 2015). As Perry and Jackson (2014) note, “Our current public policies, programs and practices in the Western world remain fundamentally disrespectful of two great interrelated gifts of our species—the remarkable malleability of [the] brain in early life and the power of relationships” (p. 5). Developing communities that support healing and resilience needs to be a collaborative group effort that includes early prevention and early intervention efforts that respect children’s developmental windows of opportunity. This includes developing a continuum of support services that span from preconception through college age and involve collaboration between caregivers, schools, public health, child welfare, mental health providers, policy makers, law enforcement, and countless other professionals and systems (Walkley and Cox 2013). Extensive core training about brain development, trauma, environmental shaping of trauma, and the role of neurobiologically-informed approaches across disciplines is essential (Perry and Jackson 2014; Ryan et al. 2017; Walkley and Cox 2013).

Policy and Practice Implications

Primary Prevention: Maximizing Windows of Opportunity

Alleviating Toxic Environmental Elements

Given the key role of ecological contexts in shaping developing brains, it is important that efforts towards healing trauma are also directed towards healing environmental contexts. Addressing the effects of poverty related stressors on brain development could include strengthening earned income tax credits and housing subsidy programs (Blair and Raver 2016). Addressing technology-induced “relational poverty” (Perry and Szalavitz 2017), characterized by the dilution of relational capacities through constant technology use, could involve investing in media literacy education and programs that encourage less screen time for children (Perry and Szalavitz 2017; Turkle 2012). Additionally, of utmost importance is working to dismantle systems of oppression and “…the toxic milieu of racism that triggers chronic stress and many other epigenetic risks” (Brendtro and Mitchell 2013, p. 6). This includes a professional obligation to advocate for social justice. Policy can be implemented to require implicit bias training for all individuals in authority positions engaging with youth, including teachers and law enforcement. Clinicians can support youth as they deconstruct the discourses of toxic environments by engaging in solutogenic, affirming practice that externalizes issues of race and oppression while giving voice to subjugated stories and engaging in narratives of rehumanization and resilience (Lee 2016). Clinicians can also work to connect children and families to environmental resources that can mitigate the effects of various types of oppression.

Promoting Healthy Relationships and Supports

Given the neurosequential nature of development, early prevention and intervention strategies that promote positive healthy relationships and social supports during developmental windows of opportunity are vital (De Bellis and Zisk 2014; Lupien et al. 2016). This includes primary prevention strategies such as public education and policy regarding healthy brain development. Taking into account an understanding of epigenetic trauma transmission, primary prevention should begin even prior to conception. Risk identification and the development of interventions aimed at prevention should include screening for maltreatment histories in women who are in the early stages of pregnancy or intend to become pregnant (Buss et al. 2017).

Secondary Prevention and Intervention: Building Buffering Experiences

Early Identification/Intervention

Secondary prevention and intervention should include early identification and intervention programs to support children at risk of suboptimal development or who have experienced developmental trauma. Programs should be aimed at building buffering experiences and connecting caregivers to support systems. Policy should include increased funding and access to early intervention programs with home visitation programs before, during, and after pregnancy (De Bellis and Zisk 2014; Perry and Jackson 2014).

Supporting Caregivers

Children’s level of security with primary caregivers in the first 2 years of life is a key indicator of future resiliency (Van der Kolk 2015). As noted by Van der Kolk (2015), “Safe and protective early relationships are critical to protect children from long term problems…even parents with their own genetic vulnerabilities can pass on that protection to the next generation provided they are given the right support” (p. 156–157). Given current child maltreatment statistics, we need to do better at providing caregivers the support they need to nurture children. This requires moving away from blaming caregivers to critically looking at how we are not providing caregivers with an adequate system of social support.

Strengthening Systems of Support

Strengthening systems of support includes fostering neurodevelopmentally-informed, trauma-informed systems that are client centered and take into account evidence-based practices. A multidisciplinary, collaborative approach with steps taken at various system levels is indicated.

Child Welfare/Foster Care

Workforce initiatives for building trauma-informed child welfare programs can include implementing trauma-informed training, evidence-based practice, and leadership teams (Fraser et al. 2014; Kenny et al. 2017). Trauma-informed care requires practices that do not “exacerbate…or replicate the relational impermanence and trauma of the child’s life” (Ludy-Dobson and Perry 2010, p. 39). This includes reducing foster care placement instability (Fisher et al. 2013). Interventions should include identification and support for populations most at risk of placement instability as well as more general screening and matching processes for youth and foster caregivers. In a recent study “30% of LGBTQ youth reported physical violence by family members after disclosing their sexual orientation or gender identity” and 19.6% of LGB youth in foster care had caregivers request a placement move compared with 8.6% of heterosexual youth in foster care (Martin et al. 2016, p. 8). This speaks to the need for processes to match LGBTQ youth in foster care to LGBTQ affirming homes (Martin et al. 2016).

Schools/Childcare

Improved access to good childcare is essential in addressing the ecological context of healing. Perry and Jackson (2014) call for more funding and standards for developmentally-informed childcare settings with smaller ratios of children to teachers, decreased screen time for children, and increased funding for paying and training teachers. Teacher training should include an understanding of sequential brain development, the role of integrating somatosensory regulating processes, the importance of developmentally-appropriate relational and cognitive expectations, and the importance of relationally-based rather than punitive discipline models (Perry 2014, 2016; Ryan et al. 2017).

Criminal Justice System

The criminal justice system can serve a key role in mitigating the wounds of complex trauma by working to decrease “authority-perpetrated, discriminatory and race-based violence” enacted on young Black males (Ashing et al. 2017, p. 511). This could include requiring implicit bias training for all officials in authority positions.

Mental Health Services

A key policy implication is the need for improved access to mental health services including home visitation services. Mental health and medical professionals should have adequate core training in neurodevelopmental approaches in order to apply evidence-based, neurodevelopmentally-informed practice. This includes a shift away from one-size-fits all treatment and categorical diagnosis-based treatment to treatment based on each individual’s unique brain profile (The ChildTrauma Academy 2015; Gaskill and Perry 2017). Neurodevelopmental considerations should be included at all program and policy levels and should be monitored for equitable application. For instance, in an interview with Dr. Bruce Perry, it was noted that “Foster children in the US with mental health problems received three and eight times more psychotropic medications than children with the same neuropsychic problems but not in the foster-care system” (MacKinnon 2012, p. 215–216). Additionally, day program and inpatient levels of care need to find ways to implement structure and safety without engaging in re-traumatizing and punitive practices including overt and covert manifestations of coercive environments (American Association of Children’s Residential Centers 2014).

Challenges of Addressing the Ecological Context of Healing

Addressing the ecological context of healing can seem like a Sisyphean task given the multiple systems involved in producing change. As Perry and Jackson (2014) discuss, the stress response system activates when exposed to novelty, resulting in the experience of change as threatening and producing a context in which changing programs and systems feels especially difficult. Shifting systems and cultures is difficult, but not impossible—especially when individuals across disciplines are able to join together in taking small steps forward. As Brendtro (2015) notes, “…healthy environments and cultures produce resilient brains” (p. 43). To address trauma transmission, we need to begin with doing a better job holding and caring for each other.

Avoiding “Ancestral-Environmental Epigenetic Determinism”

“…the emotional brain evolved in kinship societies where sharing was essential to survival. Charles Darwin saw sympathy as the strongest human instinct, but simplistic ‘survival of the fittest’ views obscure that wisdom. A better rule for human cultures is ‘survival of the kindest’” (Brendtro 2015, p. 42).

Across theoretical orientations, trauma transmission involves bodies adapting to harsh environments as best as they can, whether through relational patterns, socialization, narrative communication, or epigenetically-mediated genetic expression. Epigenetic research on trauma transmission tends to lie at the two extremes of searching for a pharmacological magic bullet to wipe away epigenetic traces of trauma and becoming resigned to “ancestral-environmental epigenetic determinism” (Jablonka 2016, p. 43; see also Kellermann 2013; Nugent et al. 2016).

In terms of the search for a pharmacological means of reversing methylation effects, “It is important to note that methylation is not good or bad in itself—it is an environmentally primed adaption that may or may not be adaptive to future environments” (van IJzendoorn et al. 2011, p. 307). Attempting methylation reversal via pharmacological means may be risky in that it may affect methylation patterns that are essential for stable cell differentiation and for development of resilience (Hurley 2015). Fostering healthy “healing communities” may be a better approach since “…healing and recovery are impossible—even with the best medications and therapy in the world—without lasting caring connections to others” (Perry and Szalavitz 2017, p. 259–260).

In terms of those resigned to “ancestral-environmental epigenetic determinism” (Jablonka 2016, p. 55) or the idea that trauma will continue to persist because it is written in our bodies, it is important to remember that we have been shaped by our environment and the way in which we are shaped perpetuates merely because the environment perpetuates. At the molecular level, humans continue to adapt to environments in such a way that “…epigenetics is often reversible. When humans live in harmony, health ensues…the challenge is to transform cultures of discord into cultures of respect” (Brendtro and Mitchell 2013, p. 6). Complex trauma is not destined to persist forever, but it also cannot be magically wiped away through pharmacological means. Rather, Hans Selye, a key figure in the origin of stress research “saw altruism as the ultimate antidote to stress” (Brendtro 2015, p. 46). To heal the person, we must first work to heal the environment. For our societies to truly thrive, we must be kind to one another.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge and thank Kelly Pratt, LICSW of Simmons School of Social Work for supporting this work and for her commitment to approaching healing through kindness. Additionally, the author would like to thank Lisa Harrison, MBA for support of this work and for proofreading efforts.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

As a review article, no human subjects were involved. The case illustrations are hypothetical composite illustrations and do not include identifying information of any clients.

References

- American Association of Children’s Creating Non-Coercive Environments. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth. 2014;31(2):114–119. doi: 10.1080/0886571X.2014.918436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing KT, Lewis ML, Walker VP. Thoughts and response to authority-perpetrated, discriminatory, and race-based violence. JAMA Pediatrics. 2017;171(6):511–512. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barfield S, Dobson C, Gaskill R, Perry BD. Neurosequential model of therapeutics in a therapeutic preschool: Implications for work with children with complex neuropsychiatric problems. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2012;21(1):30–44. doi: 10.1037/a0025955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair Clancy, Raver C. Cybele. Poverty, Stress, and Brain Development: New Directions for Prevention and Intervention. Academic Pediatrics. 2016;16(3):S30–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers ME, Yehuda R. Intergenerational transmission of stress in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(1):232–244. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga LL, Mello MF, Fiks JP. Transgenerational transmission of trauma and resilience: a qualitative study with Brazilian offspring of Holocaust survivors. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):134. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt K, Diel J, Feder J, Lillas C. A problem in our field. Journal of Zero to Three. 2012;32(4):42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Brendtro LK. Our resilient brain: nature’s most complex creation. Reclaiming Children & Youth. 2015;24(2):41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Brendtro LK, Mitchell ML. Deep brain learning: healing the heart. Reclaiming Children & Youth. 2013;22(1):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell T, Waters L, Stokes H. Teaching with strengths in trauma-affected students: a new approach to healing and growth in the classroom. American Journal Of Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85(1):3–9. doi: 10.1037/ort0000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns S. Barnett, Szyszkowicz J. Kasia, Luheshi Giamal N., Lutz Pierre-Eric, Turecki Gustavo. Plasticity of the epigenome during early-life stress. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2018;77:115–132. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Entringer S, Moog NK, Toepfer P, Fair DA, Simhan HN, Wadhwa PD. Review: Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood maltreatment exposure: implications for fetal brain development. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;56(5):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao-Lei L, Massart R, Suderman MJ, Machnes Z, Elgbeili G, Laplante DP, King S. DNA methylation signatures triggered by prenatal maternal stress exposure to a natural disaster: project ice storm. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, Van der Kolk B. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35(5):390–398. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Zisk A. The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2014;23(2):185–222. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nooyer KM, Lingard MW. Applying principles of the neurosequential model of therapeutics across an adolescent day program and inpatient unit. Australasian Psychiatry. 2017;25(2):150–153. doi: 10.1177/1039856216658824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGregorio LJ. Intergenerational transmission of abuse: Implications for parenting interventions from a neuropsychological perspective. Traumatology. 2013;19(2):158–166. doi: 10.1177/1534765612457219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Mannering AM, Van Scoyoc A, Graham AM. A translational neuroscience perspective on the importance of reducing placement instability among foster children. Child Welfare. 2013;92(5):9–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TB, Russig H, Weiss IC, Gräff J, Linder N, Michalon A, Mansuy IM. Epigenetic transmission of the impact of early stress across generations. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(5):408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JG, Griffin JL, Barto BL, Lo C, Wenz-Gross M, Spinazzola J, Bartlett JD. Implementation of a workforce initiative to build trauma-informed child welfare practice and services: findings from the Massachusetts child trauma project. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;44:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.06016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gapp K, Jawaid A, Sarkies P, Bohacek J, Pelczar P, Prados J, Mansuy IM. Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nature Neuroscience. 2014;17(5):667–669. doi: 10.1038/nn.3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskill RL, Perry BD. A neurosequential therapeutics approach to guided play: Play therapy, and activities for children who won’t talk. In: Malchiodi CA, Crenshaw DA, editors. What to do when children clam up in psychotherapy: Interventions to facilitate communication. New York: The Guildford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Geller SM, Porges SW. Therapeutic presence: Neurophysiological mechanisms mediating feeling safe in therapeutic relationships. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2014;24(3):178–192. doi: 10.1037/a0037511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman RD. The transgenerational trauma and resilience genogram. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2013;26(3/4):386–405. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2013.820172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gröger N, Matas E, Gos T, Lesse A, Poeggel G, Braun K, Bock J. The transgenerational transmission of childhood adversity: behavioral, cellular, and epigenetic correlates. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2016;123(9):1037–1052. doi: 10.1007/s00702-016-1570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, D. (2015). Grandma’s experiences leave a mark on your genes. Discover Magazine. Retrieved from http://discovermagazine.com/2013/may/13-grandmas-experiences-leave-epigenetic-mark-on-your-genes.

- Isles AR. Neural and behavioral epigenetics: what it is, and what is hype. Genes, Brain & Behavior. 2015;14(1):64–72. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka E. Cultural epigenetics. The Sociological Review Monographs. 2016;64(1):42–60. doi: 10.1111/2059-7932.12012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keating DP. Transformative role of epigenetics in child development research: commentary on the special section. Child Development. 2016;87(1):135–142. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermann NP. Epigenetic transmission of holocaust trauma: can nightmares be inherited? The Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences. 2013;50(1):33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MC, Vazquez A, Long H, Thompson D. Implementation and program evaluation of trauma-informed care training across state child advocacy centers: an exploratory study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;73:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.11.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic M, Lim S, Gudsnuk K, Champagne FA. Sex-specific and strain-dependent effects of early life adversity on behavioral and epigenetic outcomes. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2013;4(78):1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labonté B, Suderman M, Maussion G, Navaro L, Yerko V, Mahar I, Turecki G. Genome-wide epigenetic regulation by early-life trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(7):722–731. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. R. S. (2016). A trauma-informed approach to affirming the humanity of African American boys and supporting healthy transitions to manhood. In Boys and Men in African American families (pp. 85–92). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Ludy-Dobson CR, Perry BD. The role of healthy relational interactions in buffering the impact of childhood trauma. In: Gil E, editor. Working with children to heal interpersonal trauma: The power of play. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 26–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, Ouellet-Morin I, Herba CM, Juster R, McEwen BS. From vulnerability to neurotoxicity: A developmental approach to the effects of stress on the brain and behavior. In: Spengler D, Binder E, editors. Epigenetics and neuroendocrinology: Clinical focus on psychiatry. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. pp. 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon L. The neurosequential model of therapeutics: an interview with Bruce Perry. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy. 2012;33(3):210–218. doi: 10.1017/aft.2012.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Down L, Erney R. Out of the shadows: Supporting LGBTQ youth in child welfare through cross-system collaboration. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Social Policy; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonté B, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12(3):342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Transgenerational epigenetic contributions to stress responses: fact or fiction? Plos Biology. 2016;14(3):1–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent NR, Goldberg A, Uddin M. Topical review: The emerging field of epigenetics: informing models of pediatric trauma and physical health. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2016;41(1):55–64. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsv018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud N, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Prada P, Olié E, Salzmann A, Nicastro R, Huguelet P. Increased methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment: a link with the severity and type of trauma. Translational Psychiatry. 2011;1(e59):1–9. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry B, Jackson A. The long and winding road: from neuroscience to policy, program, practice. Insight Magazine: Victorian Council of Social Service. 2014;9:4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Perry BD. Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. Journal of Loss And Trauma. 2009;14(4):240–255. doi: 10.1080/15325020903004350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry BD. The neurosequential model of therapeutics in young children. In: Brandt K, Perry BD, Seligman S, Tronick E, editors. Infant and early childhood mental health: Core concepts and clinical practice. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2014. pp. 21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Perry BD. The brain science behind trauma. Education Week. 2016;26(15):28. [Google Scholar]

- Perry BD, Dobson C. Application of the Neurosequential Model (NMT) in maltreated children. In: Ford J, Courtois C, editors. Treating complex traumatic stress disorders in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. pp. 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Perry BD, Szalavitz M. The boy who was raised as a dog: And other stories from a child psychiatrist’s notebook-what traumatized children can teach us about loss, love and healing. New York: Basic Books; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild B. Applying the brakes. Psychotherapy Networker. 2004;28(1):42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K, Lane SJ, Powers D. A multidisciplinary model for treating complex trauma in early childhood. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2017;26(2):111–123. doi: 10.1037/pla0000044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DJ. The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Szyf M. DNA methylation, behavior and early life adversity. Journal of Genetics and Genomics. 2013;40(7):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, Samson JA. Annual research review: enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2016;57(3):241–266. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The ChildTrauma Academy. (2015). The neurosequential model of therapeutics as evidence-based practice. Retrieved January 28, 2017, from https://childtrauma.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/NMT_EvidenceBasedPract_5_2_15.pdf.

- Turkle S. Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. New York: Basic Books; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Price LH, Marsit C, Walters OC, Carpenter LL. Childhood adversity and epigenetic modulation of the leukocyte glucocorticoid receptor: preliminary findings in healthy adults. PloS One. 2012;7(1):e30148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2007). Child maltreatment 2005. Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Child maltreatment 2015. Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Van der Kolk BA. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Penguin Books; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Ebstein RP. Methylation matters in child development: toward developmental behavioral epigenetics. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5(4):305–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00202.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walkley M, Cox TL. Building trauma-informed schools and communities. Children & Schools. 2013;35(2):123–126. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdt007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7(8):847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]