Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of publicity (private, public) and medium (face-to-face, cyber) on the associations between attributions (i.e., self-blame, aggressor-blame) and coping strategies (i.e., social support, retaliation, ignoring, helplessness) for hypothetical victimization scenarios among 3,442 adolescents (age range 11–15 years; 49% girls) from China, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, India, Japan, and the United States. When Indian and Czech adolescents made more of the aggressor-blame attribution, they used retaliation more for public face-to-face victimization when compared to private face-to-face victimization and public and private cyber victimization. In addition, helplessness was used more for public face-to-face victimization when Chinese adolescents utilized more of the aggressor-blame attribution and the self-blame attribution. Similar patterns were found for Cypriot adolescents, the self-blame attribution, and ignoring. The results have implications for the development of prevention and intervention programs that take into account the various contexts of peer victimization.

Keywords: Cyber victimization, Cyberbullying, Victimization, Coping, Attribution, Culture

Introduction

Face-to-face and cyber victimization impact the psychosocial and academic adjustment of Western and non-Western adolescents (Smith, Cowie, Olafsson, & Liefootghe, 2002). Just as victimization can occur in the face-to-face and cyber contexts, it can also occur publically or privately. Research has focused on adolescents’ interpretations of their peers’ behaviors (i.e., attributions), particularly their peers’ aggressive behaviors (Burgess et al. 2006; Garner and Lemerise 2007; Graham and Juvonen 1998; Prinstein et al. 2005). Attributions also influence adolescents’ coping strategies for victimization (Shelley and Craig 2009; Visconti et al. 2013). Although there is some literature linking attributions and coping strategies, little attention has been given to whether these associations might vary based on the publicity (public, private) and medium (face-to-face, cyber) of victimization. Furthermore, researchers have also found that culture impacts children’s and adolescents’ attributions and coping strategies, though it is not clear how culture might influence the associations between these variables (Crystal 2000; Essau and Trommsdorff 1996; Flammer et al. 1995; Hui 2001; Kawabata et al. 2013; Marsella and Dash-Scheuer 1988; Wright et al. 2014). To address this gap in the literature, the present study investigated the influence of publicity, medium, and attributions on coping strategies among adolescents from six countries, including China, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, India, Japan, and the United States (U.S.).

Cyber Victimization and Attributions

Adolescents’ involvement in peer victimization is influenced by specific social cognitive patterns, including biased perceptions regarding peers and hostile interpretations of emotional and behavioral cues (Garner and Lemerise 2007; Graham and Juvonen 1998; Prinstein et al. 2005). In the literature on peer victimization and social cognitive patterns, victimized children attributed peer victimization more often to themselves (i.e., self-blame) and to their peers when compared to nonvictimized children (Graham and Juvonen 1998; Mathieson et al. 2011; Troop-Gordon and Ladd 2005). Self-blame attributions are related to psychosocial adjustment difficulties, including depression and anxiety (Yeh 2011). This attribution is not related to later bullying and aggressive behaviors. On the other hand, aggressor-blame attributions (e.g., blaming bullying or aggression on the perpetrator’s psychological characteristics) mitigate psychosocial adjustment difficulties, but these attributions promote the perpetration of bullying and aggressive behaviors (Boxer and Tisak 2003; Coie and Pennington 1976; Yeager et al. 2013).

Little attention has been given to adolescents’ attributions for cyber victimization, with most of these studies applying attributions for face-to-face victimization to cyber victimization (Ang and Goh 2010; Pornari and Wood 2010). Cyber victimization and face-to-face victimization might differ regarding attributions as information and communication technologies include unique features. There are more social cues, like facial expressions, present in face-to-face interactions. Given that there are more cues present in these interactions, it might be easier to identify intentionality. On the other hand, information and communication technologies lack various nonverbal and intention cues. The lack of cues makes it more difficult to determine causality (Tokunaga 2010). Due to differences in cues for face-to-face interactions and cyber interactions, it might be likely that cyber victimization is perceived as less hostile than face-to-face victimization (Smith et al. 2008). Providing support for this proposal, Shapka (2012) found that Canadian cybervictims typically interpreted cyber victimization as a joke when someone they did not know experienced it. Research has also revealed that some cybervictims interpreted their own victimization as a joke and so did some cyberbullies who were also victimized online (Balaji and Chakrabarti 2010; Hinduja and Patchin 2012). One proposal for these findings is that victims, bystanders, and perpetrators might perceive aggressive or hostile interactions through information and communication technologies as normative online behaviors and interactions (Runions et al. 2013). Consequently, they might be likely to diminish the impact of cyber victimization and dismiss this type of aggression as a joke or something that should not be taken seriously.

The perpetration or suppression of bullying and aggression are influenced by adolescents’ cultural norms and values (Chen and French 2008). Cooperation and compliant behaviors are emphasized in collectivistic cultures, including China and Japan. These cultures also suppress aggression, and reinforce interdependence and the maintenance of relationships with others in their society (Matsumoto and Juang 2004). Countries, like Cyprus and India, endorse both collectivism and individualism, making these countries not exclusively collectivistic or individualistic (Georgiou 2005; Verma 2001). Independent self-construals, self-reliance, and freedom of choice are values emphasized in individualistic cultures, like the Czech Republic and the U.S. Given different cultural values, some research has investigated cross-cultural differences in attributions between collectivistic and individualistic cultures. In this literature, Crystal (2000) found that external attributions were typically emphasized among children and adolescents from the U.S., while Japanese children and adolescents used more internal attributions. Internal attributions were used to blame the self and protect the group, and external attributions were used to emphasize individual protection and self-enhancement. Similar results were found by Hui (2001). In Hui’s study, he examined Chinese students’ and teachers’ attributions regarding students’ academic abilities. Chinese students and teachers typically attributed students’ academic abilities to internal factors, like students’ effort and motivation. These two studies (i.e., Crystal 2000; Hui 2001) focused on academic abilities, which might trigger different attributions than for peer victimization.

Some research has focused on attributions for peer victimization in different cultures. In one study, 59% of Chinese adolescents in the sample attributed relational victimization to aggressor-blame, 24% to self-blame, and 17% to conflict among the perpetrator and victim (Wright et al. 2014). Comparing Japanese and European American children, Kawabata and colleagues (2013) found that the hostile attribution bias was stronger for relational victimization among Japanese children. This moderating effect was not found for European American children. To explain these associations, Kawabata et al. proposed that Japanese children might feel more humiliation and shame by being negatively evaluated by peers, which could also result in them losing face, which is unique to Asian cultures. Such cultural values might contribute to more hostile attributional biases in these cultures. A potential reason for the differences in Wright et al.’s (2014) and Kawabata and colleagues’ (2013) findings from Crystal’s (2000) and Hui’s (2001) might be the focus on different behaviors, academic abilities vs. relational victimization. Differences in these findings suggest that specific behaviors trigger unique attributions for children and adolescents, which might also apply to the publicity of victimization, and type of victimization, face-to-face vs. cyber victimization. Public victimization might be similar to relational victimization as it could result in adolescents from collectivistic cultures being shamed by negative peer evaluations.

Cyber Victimization and Coping Strategies

Stressful situations elicit attempts to reduce or remove the negative effects associated with the situation. To deal with stressful situations, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) proposed two levels of appraisal, primary appraisal and secondary appraisal. Primary appraisal involves the meaning people ascribe to stressful situations, which is impacted by people’s values, commitments, and goals (Park and Folkman 1997). Stress typically violates people’s values and disrupts their commitments and goals. The evaluation of various coping strategies and decisions about the outcomes of these strategies is known as secondary appraisal (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Once people decide on a coping strategy or coping strategies, they then enact the chosen strategy or strategies. Four coping strategies are typically investigated in relation to peer victimization. These strategies include retaliation (e.g., reactive responses to the bully or getting revenge on the bully), social support (e.g., asking someone for help), helplessness (e.g., not taking control over the situation), and ignoring (Perren et al. 2012).

Research has revealed cultural differences in the coping strategies used for peer victimization. In this literature, Lam and Zane (2004) found that Asian Americans used indirect control coping strategies to deal with peer victimization. On the other hand, they found that European Americans utilized direct control coping strategies. The decision to use different coping strategies is influenced by people’s belief systems. Consequently, people utilize coping strategies that match their cultural contexts (Marsella and Dash-Scheuer 1988). In particular, people from collectivistic cultures use coping strategies that fit their environments, while people from individualistic cultures employ coping strategies that fit their personal needs (Essau and Trommsdorff 1996; Flammer et al. 1995). Therefore, coping strategies that take into account others are generally used by people from collectivistic cultures. Coping strategies used by people from individualistic cultures usually focus on the self.

Other factors influence people’s decisions to use certain coping strategies. The publicity of victimization, specifically public victimization and private victimization, and type of victimization, including face-to-face victimization and cyber victimization, might impact adolescents’ coping strategies. Although little attention has focused on this proposal, some attention has been given to how the emotional impact of stressful situations relate to coping strategies. When greater emotional impact is perceived in a stressful situation, people utilize various coping strategies (Terry 1994). The literature on the differences in emotional impact between face-to-face victimization and cyber victimization has been mixed, with some results indicating that adolescents perceive greater emotional impact for face-to-face victimization, while other findings suggest that they report greater emotional impact for cyber victimization (Ortega et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2008). The mixed findings might be the result of various definitions and methodologies used to assess victimization. Despite not focusing on coping strategies, Sticca and Perren (2013) examined differences in adolescents’ perceptions of harm for public and private face-to-face and cyber victimization. As a broader form of impact, perceived harm includes various types of impacts, such as emotional, physical, and social impacts. The findings revealed that greater harm was perceived for public victimization vs. private victimization and that cyber victimization elicited greater perceptions of harm than face-to-face victimization, though the effect sizes of type of victimization were small. Based on these findings and Terry’s (1994), coping strategies might vary depending on the publicity of victimization and the type of victimization, with public and cyber forms of victimization being perceived as the most emotionally harmful.

Attributions have also been found to influence adolescents’ coping strategies for victimization. Self-blame is linked to externalizing coping and distancing coping (Shelley and Craig 2009). Furthermore, adolescents’ attributions of personal behavior (e.g., did something that made the person angry) and mutual antipathy (e.g., they just do not get along) were associated positively with the coping strategy of retaliation (Visconti et al. 2013). Believing that one’s peers were jealous of them related to adolescents’ use of social support as a coping strategy. Thus far, no research has focused on whether the relationship between attributions and coping strategies might be impacted by differences in publicity and different types of victimization.

The Present Study

There are considerable gaps in the literature concerning the impact of publicity (public, private) and medium (face-to-face, cyber) on the associations between attributions and coping strategies for victimization among adolescents from China, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, India, Japan, and the U.S., after controlling for gender, individualism, and collectivism. Gender was controlled for due to inconsistent findings regarding gender, attributions, and coping strategies for hypothetical face-to-face victimization and cyber victimization (Hampel and Petermann 2005; Wright et al. 2017). There were four hypothetical victimization scenarios for which adolescents indicated their attributions and coping strategies, including public face-to-face victimization, private face-to-face victimization, public cyber victimization, and private cyber victimization. Due to the lack of research focused on the role of publicity and medium in the relationships between attributions and coping strategies, the present study was exploratory and consequently no specific hypotheses were posed.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this study included 3,432 adolescents between the ages of 11 and 15 from China (n = 673, 46.7% girls), Cyprus (n = 470, 49.8% girls), the Czech Republic (n = 537, 52.1% girls), India (n = 480, 46.5% girls), Japan (n = 460, 52.6% girls), and the U.S. (n = 812, 50.2% girls). They were from two urban Chinese schools, four urban Cypriot schools, eighteen urban and rural schools in the Czech Republic, six urban schools in India, two suburban schools in Japan, and seven urban and suburban schools from the U.S. The data were collected in the Fall of 2013 for all participants, except for Japanese adolescents. These participants had their data collected in July 2014. July represents the beginning of the school year for Japanese schools, while the fall marked the beginning of the year for the schools in the other countries. Income data were not collected.

Missing Data

Of the data, 0.9% were missing. This yielded 270 incomplete records. There were 47 missing from the Chinese sample, 109 from the Cypriot sample, 87 from the Czech Republic, 5 from the Indian sample, 21 from the Japanese sample, and 1 from the U.S. sample. The missing data were dealt with using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation under the missing at random (MAR) assumption (Enders 2010).

Procedures

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained by the researchers from their respective university and American Psychological Association ethics were followed throughout the conduction of this study. To recruit schools for the study, research personnel contacted school principals through emails or calls to discuss the purpose of the study and how adolescents could participate. Once school principals gave their permission, a classroom announcement was made. During the announcement, research personnel described the purpose of the study, how adolescents could participate, and what they would do if they were to participate. After the classroom announcements, parental permission slips were sent home with adolescents for them to give to their parent(s) or guardian(s). Parental permission slips were then returned to adolescents’ classrooms. Japan and the Czech Republic followed different consenting procedures. In these countries, school principals provided their consent for adolescents’ participant, because it is believed that the school principal has the best interest of the children, similar to parents’ interest. Despite different consent procedures, all data were collected at adolescents’ schools during regular school hours. Before participating, adolescents provided their own assent to participate in the study, with none refusing to participate. Measures were translated from English into the main language of adolescents’ country of origin. They completed a measure on their individualism and collectivism, followed by a measure on their attributions and coping strategies for public and private forms of face-to-face and cyber victimization situations.

Measures

Individualism and Collectivism

This questionnaire asked adolescents to rate their endorsement of collectivism and individualism on a scale of 1 (Absolutely disagree) to 9 (Absolutely agree) (Li et al. 2010). Eight items assessed individualism (e.g., Winning is everything) and eight assessed collectivism (e.g., Family members should stick together, no matter what sacrifices are required), which resulted in a total of sixteen items for this questionnaire. The items were averaged to form separate scores on individualism and collectivism. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.70 to 0.84 for individualism and 0.79 to 0.87 for collectivism.

Attributions and Coping Strategies for Public and Private Forms of Face-to-Face Victimization and Cyber Victimization Situations

Adolescents read four different victimization vignettes, which varied based on the medium (face-to-face, cyber) and publicity (public, private), resulting in four situations: public face-to-face victimization, private face-to-face victimization, public cyber victimization, and private cyber victimization. The public face-to-face victimization situation read as follows: “A classmate says something really nasty and humiliating to you at school in front of everyone.” Bold font and an underline was added under “at school in front of everyone” to highlight that this victimization situation was public and occurred face-to-face. To specify when a situation was private, the “in front of everyone” was replaced with “but nobody is around to hear/see it.” In addition, the “at school” was replaced with “online” to indicate that the situation was about cyber victimization. After each vignette, adolescents rated self-blame and aggressor-blame attributions. There were 5 self-blame items, including “If I were cooler, I wouldn’t get picked on,” while there was 1 item for aggressor-blame, i.e., “This peer did this to me because of their personality.” These items were rated on a scale of 1 (Definitely would NOT think) to 5 (Definitely WOULD think) (Graham and Juvonen 1998; Wright et al. 2014). Adolescents also rated six coping strategy items on a scale of 1 (Definitely would NOT do) to 5 (Definitely WOULD do) (Perren et al. 2012). Three items were included for social support (e.g., I would talk to my family about it), one for retaliation (i.e., I would get back at him/her), one for ignoring (i.e., I would decide to ignore him/her), and one for helplessness (i.e., I would do not because I do not want to make it worse). The self-blame attribution and social support were averaged separately, resulting in separate scores for this attribution and this coping strategy. Cronbach’s alphas were between 0.49 and 0.63 for self-blame, and 0.48 and 0.83 for social support.

Analytic Strategy

A series of multiple group multilevel models were conducted in Mplus 7.4 with repeated measures at level 1 nested in students at level 2, comparing countries of origin for each coping strategy as dependent variable (Hox 2010; Snijders and Bosker 2012). At level 1, attributions (self-blame and aggressor-blame), publicity (0 = private, 1 = public), medium (0 = face-to-face, 1 = cyber), and interactions between publicity and medium, attributions and publicity, attributions and medium, and attributions, publicity, and medium were included as predictors. At level 2, gender, individualism, and collectivism were included as covariates in the model. Maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR) with a sandwich estimator to take into account the non-independence of observations due to the class level was used to estimate the models.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the study’s main variables and the results of the multilevel models are presented in this section. Interaction plots are also included with 95% confidence intervals when the interaction effect is statistically significant. Means and standard deviations of all attributions and coping strategies for public and private forms of face-to-face victimization and cyber victimization in each country are presented in Table 1. Results from the multilevel models, with all βs (i.e., standardized estimates) and p-values for each of the coping strategies and across the six countries, are included in Table 2. Overall, effect sizes were small.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of all outcome variables for face-to-face vs. cyber victimization and private vs. public victimization

| F2F | Cy | Pri | Pub | F2F Pri | Cy Pri | F2F Pub | Cy Pub | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vic | Vic | Vic | Vic | Vic | Vic | Vic | Vic | |

| M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | |

| (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | |

| Self-Blame | ||||||||

| China | 1.84 | 1.74 | 1.72 | 1.85 | 1.76 | 1.68 | 1.91 | 1.79 |

| (0.72) | (0.71) | (0.72) | (0.71) | (0.72) | (0.72) | (0.71) | (0.71) | |

| Cyprus | 2.26 | 2.10 | 2.12 | 2.24 | 2.14 | 2.11 | 2.39 | 2.10 |

| (0.78) | (0.81) | (0.80) | (0.80) | (0.78) | (0.82) | (0.77) | (0.80) | |

| Czech Republic | 2.24 | 2.11 | 2.10 | 2.25 | 2.14 | 2.06 | 2.33 | 2.17 |

| (0.72) | (0.73) | (0.74) | (0.70) | (0.76) | (0.72) | (0.67) | (0.73) | |

| India | 2.43 | 2.47 | 2.49 | 2.42 | 2.46 | 2.51 | 2.40 | 2.43 |

| (0.82) | (0.89) | (0.86) | (0.85) | (0.81) | (0.91) | (0.83) | (0.87) | |

| Japan | 2.57 | 2.51 | 2.52 | 2.56 | 2.54 | 2.50 | 2.60 | 2.52 |

| (0.89) | (0.91) | (0.91) | (0.89) | (0.91) | (0.91) | (0.87) | (0.91) | |

| United States | 2.42 | 2.25 | 2.23 | 2.44 | 2.25 | 2.22 | 2.59 | 2.28 |

| (0.84) | (0.88) | (0.86) | (0.86) | (0.83) | (0.89) | (0.82) | (0.86) | |

| Aggressor-Blame | ||||||||

| China | 2.86 | 2.78 | 2.74 | 2.90 | 2.75 | 2.74 | 2.97 | 2.82 |

| (1.27) | (1.30) | (1.31) | (1.26) | (1.30) | (1.32) | (1.22) | (1.29) | |

| Cyprus | 2.90 | 2.85 | 2.83 | 2.92 | 2.81) | 2.84 | 2.99 | 2.86 |

| (1.40) | (1.45) | (1.44) | (1.41) | (1.44) | (1.44) | (1.36) | (1.46) | |

| Czech Republic | 3.26 | 3.20 | 3.17 | 3.29 | 3.24 | 3.10 | 3.29 | 3.30 |

| (1.16) | (1.24) | (1.22) | (1.18) | (1.17) | (1.27) | (1.16) | (1.20) | |

| India | 2.89 | 2.85 | 2.83 | 2.90 | 2.92 | 2.74 | 2.86 | 2.95 |

| (1.44) | (1.46) | (1.43) | (1.46) | (1.45) | (1.41) | (1.42) | (1.51) | |

| Japan | 2.85 | 2.81 | 2.85 | 2.82 | 2.88 | 2.81 | 2.82 | 2.81 |

| (1.35) | (1.32) | (1.32) | (1.34) | (1.35) | (1.30) | (1.36) | (1.34) | |

| United States | 3.25 | 3.14 | 3.18 | 3.20 | 3.20 | 3.17 | 3.29 | 3.11 |

| (1.27) | (1.33) | (1.34) | (1.26) | (1.31) | (1.37) | (1.24) | (1.29) | |

| Social Support | ||||||||

| China | 2.45 | 2.34 | 2.46 | 2.35 | 2.56 | 2.36 | 2.37 | 2.32 |

| (1.05) | (1.11) | (1.02) | (1.14) | (0.97) | (1.06) | (1.12) | (1.16) | |

| Cyprus | 2.97 | 3.00 | 3.09 | 2.88 | 3.07 | 3.11 | 2.88 | 2.89 |

| (1.03) | (1.09) | (1.03) | (1.08) | (1.00) | (1.07) | (1.06) | (1.11) | |

| Czech Republic | 3.05 | 2.93 | 3.10 | 2.88 | 3.15 | 3.05 | 2.94 | 2.82 |

| (1.02) | (1.02) | (0.99) | (1.04) | (0.97) | (1.01) | (1.05) | (1.02) | |

| India | 2.67 | 2.64 | 2.73 | 2.57 | 2.75 | 2.72 | 2.59 | 2.56 |

| (1.06) | (1.12) | (1.05) | (1.13) | (0.98) | (1.13) | (1.14) | (1.12) | |

| Japan | 2.88 | 2.96 | 2.91 | 2.91 | 2.89 | 2.95 | 2.87 | 2.96 |

| (1.20) | (1.28) | (1.19) | (1.39) | (1.12) | (1.26) | (1.28) | (1.29) | |

| United States | 3.21 | 3.11 | 3.30 | 3.01 | 3.30 | 3.30 | 3.11 | 2.92 |

| (1.16) | (1.22) | (1.08) | (1.28) | (1.02) | (1.15) | (1.28) | (1.27) | |

| Retaliation | ||||||||

| China | 1.78 | 1.70 | 1.76 | 1.72 | 1.81 | 1.72 | 1.75 | 1.73 |

| (1.17) | (1.17) | (1.17) | (1.17) | (1.16) | (1.18) | (1.19) | (1.15) | |

| Cyprus | 2.94 | 2.89 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 3.03 | 2.98 | 2.86 | 2.81 |

| (1.59) | (1.59) | (1.61) | (1.57) | (1.62) | (1.59) | (1.57) | (1.58) | |

| Czech Republic | 2.24 | 2.17 | 2.32 | 2.18 | 2.28 | 2.08 | 2.20 | 2.26 |

| (1.23) | (1.23) | (1.19) | (1.28) | (1.20) | (1.16) | (1.27) | (1.29) | |

| India | 2.96 | 2.98 | 3.00 | 2.95 | 2.98 | 3.02 | 2.95 | 2.95 |

| (1.51) | (1.43) | (1.48) | (1.46) | (1.52) | (1.45) | (1.50) | (1.42) | |

| Japan | 2.59 | 2.55 | 2.66 | 2.48 | 2.73 | 2.59 | 2.45 | 2.51 |

| (1.28) | (1.31) | (1.27) | (1.32) | (1.25) | (1.29) | (1.29) | (1.34) | |

| United States | 2.19 | 2.13 | 2.27 | 2.05 | 2.29 | 2.25 | 2.08 | 2.00 |

| (1.32) | (1.30) | (1.33) | (1.27) | (1.33) | (1.34) | (1.30) | (1.24) | |

| Ignoring | ||||||||

| China | 2.38 | 2.23 | 2.41 | 2.20 | 2.48 | 2.34 | 2.28 | 2.12 |

| (1.34) | (1.37) | (1.34) | (1.36) | (1.31) | (1.36) | (1.37) | (1.36) | |

| Cyprus | 3.14 | 2.98 | 3.00 | 2.83 | 3.03 | 2.98 | 2.86 | 2.81 |

| (1.44) | (1.59) | (1.61) | (1.57) | (1.62) | (1.59) | (1.57) | (1.38) | |

| Czech Republic | 3.14 | 3.06 | 2.18 | 2.23 | 2.28 | 2.08 | 2.20 | 2.26 |

| (1.35) | (1.34) | (1.19) | (1.28) | (1.20) | (1.16) | (1.27) | (1.29) | |

| India | 3.10 | 2.95 | 3.00 | 3.04 | 3.11 | 2.90 | 3.09 | 3.00 |

| (1.49) | (1.53) | (1.53) | (1.50) | (1.50) | (0.15) | (1.49) | (1.51) | |

| Japan | 3.08 | 3.03 | 3.16 | 2.94 | 3.23 | 3.10 | 2.92 | 2.95 |

| (1.31) | (1.33) | (1.30) | (1.32) | (1.29) | (1.32) | (1.31) | (1.34) | |

| United States | 3.47 | 3.40 | 3.67 | 3.23 | 3.74 | 3.55 | 3.21 | 3.26 |

| (1.35) | (1.35) | (1.26) | (1.40) | (1.23) | (1.28) | (1.41) | (1.40) | |

| Helplessness | ||||||||

| China | 2.58 | 2.61 | 2.63 | 2.56 | 2.61 | 2.66 | 2.55 | 2.56 |

| (1.44) | (1.45) | (1.44) | (1.45) | (1.42) | (1.46) | (1.46) | (1.44) | |

| Cyprus | 2.83 | 2.80 | 2.88 | 2.74 | 2.92 | 2.84 | 2.72 | 2.76 |

| (1.46) | (1.50) | (1.49) | (1.47) | (1.48) | (1.50) | (1.43) | (1.50) | |

| Czech Republic | 2.70 | 2.66 | 3.23 | 2.97 | 3.30 | 3.16 | 2.98 | 2.97 |

| (1.29) | (1.28) | (1.32) | (1.36) | (1.33) | (1.31) | (1.35) | (1.37) | |

| India | 2.82 | 2.71 | 2.74 | 2.79 | 2.72 | 2.76 | 2.70 | 2.89 |

| (1.49) | (1.51) | (1.51) | (1.49) | (1.50) | (1.53) | (1.50) | (1.49) | |

| Japan | 2.45 | 2.39 | 2.48 | 2.36 | 2.57 | 2.39 | 2.32 | 2.38 |

| (1.21) | (1.20) | (1.22) | (1.20) | (1.24) | (1.20) | (1.18) | (1.21) | |

| United States | 2.30 | 2.28 | 2.25 | 2.33 | 2.29 | 2.21 | 2.31 | 2.35 |

| (1.34) | (1.37) | (1.32) | (1.39) | (1.30) | (1.34) | (1.39) | (1.40) | |

Note. N = 3,432. F2F = Face-to-face; Cy = Cyber; Pri = Private; Pub = Public; Vic = Victimization; M = Mean; SD = Standard deviation

Table 2.

Multilevel Modeling Results: Standardized Regression Coefficients and Significance Values

| China | Cyprus | Czech Republic | India | Japan | U.S. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| The Aggressor-Blame Attribution | ||||||||||||

| Retaliation | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.10 | 0.001 | −0.09 | 0.140 | −0.25 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.056 | 0.16 | 0.004 | 0.14 | 0.001 |

| Individualism | 0.18 | 0.001 | 0.26 | 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.006 | 0.22 | 0.002 | 0.31 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| Collectivism | −0.25 | 0.001 | −0.09 | 0.140 | −0.13 | 0.059 | −0.10 | 0.198 | 0.16 | 0.004 | 0.14 | 0.001 |

| Agg−Blame | 0.06 | 0.132 | 0.04 | 0.646 | 0.04 | 0.466 | −0.10 | 0.152 | 0.12 | 0.109 | 0.04 | 0.399 |

| Pubic vs. Private | 0.04 | 0.042 | 0.09 | 0.008 | 0.06 | 0.017 | 0.03 | 0.616 | 0.07 | 0.008 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| F2F Vic vs. Cy Vic | 0.01 | 0.878 | 0.01 | 0.877 | −0.01 | 0.735 | 0.04 | 0.222 | 0.03 | 0.213 | −0.03 | 0.106 |

| Pub x Med | −0.04 | 0.126 | −0.02 | 0.466 | −0.09 | 0.010 | −0.03 | 0.539 | −0.05 | 0.064 | −0.01 | 0.738 |

| Med x Agg-Blame | 0.01 | 0.946 | 0.01 | 0.980 | 0.04 | 0.347 | 0.14 | 0.029 | 0.04 | 0.328 | 0.03 | 0.368 |

| Pub x Agg-Blame | 0.03 | 0.279 | 0.02 | 0.807 | 0.05 | 0.353 | 0.17 | 0.027 | −0.02 | 0.663 | −0.02 | 0.653 |

| Med x Pub x Agg-Blame | −0.02 | 0.624 | −0.03 | 0.573 | −0.09 | 0.035 | −0.16 | 0.012 | −0.01 | 0.767 | −0.01 | 0.776 |

| Social Support | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −0.10 | 0.010 | 0.16 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.002 | −0.17 | 0.001 | −0.11 | 0.050 | −0.09 | 0.017 |

| Individualism | 0.01 | 0.768 | −0.01 | 0.852 | −0.07 | 0.302 | 0.07 | 0.256 | −0.09 | 0.107 | −0.07 | 0.028 |

| Collectivism | 0.09 | 0.035 | 0.20 | 0.037 | 0.17 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.515 | 0.42 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.005 |

| Agg−Blame | 0.07 | 0.055 | 0.09 | 0.142 | 0.10 | 0.024 | 0.07 | 0.196 | −0.04 | 0.568 | −0.01 | 0.938 |

| Pubic vs. Private | 0.15 | 0.001 | 0.13 | 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.081 | 0.15 | 0.001 |

| F2F Vic vs. Cy Vic | −0.05 | 0.005 | −0.01 | 0.878 | −0.09 | 0.001 | −0.01 | 0.868 | 0.04 | 0.161 | −0.08 | 0.023 |

| Pub x Med | −0.05 | 0.238 | −0.01 | 0.744 | 0.04 | 0.106 | −0.08 | 0.074 | −0.04 | 0.196 | 0.02 | 0.592 |

| Med x Agg-Blame | −0.03 | 0.385 | −0.01 | 0.974 | −0.03 | 0.470 | −0.07 | 0.105 | 0.02 | 0.651 | 0.01 | 0.845 |

| Pub x Agg-Blame | −0.01 | 0.614 | −0.01 | 0.797 | 0.01 | 0.963 | −0.04 | 0.475 | 0.01 | 0.923 | −0.02 | 0.644 |

| Med x Pub x Agg-Blame | 0.04 | 0.282 | −0.02 | 0.693 | 0.03 | 0.390 | 0.08 | 0.151 | −0.01 | 0.830 | 0.05 | 0.370 |

| Helplessness | ||||||||||||

| Gender | − 0.13 | 0.003 | 0.11 | 0.053 | 0.07 | 0.199 | −0.12 | 0.001 | −0.26 | 0.001 | −0.09 | 0.047 |

| Individualism | 0.01 | 0.997 | −0.08 | 0.244 | −0.03 | 0.578 | −0.03 | 0.666 | 0.03 | 0.575 | 0.02 | 0.668 |

| Collectivism | −0.02 | 0.812 | 0.11 | 0.053 | −0.02 | 0.578 | 0.03 | 0.691 | −0.03 | 0.466 | −0.02 | 0.563 |

| Agg-Blame | 0.05 | 0.329 | −0.03 | 0.733 | 0.08 | 0.113 | −0.16 | 0.003 | 0.18 | 0.001 | −0.03 | 0.516 |

| Pubic vs. Private | 0.03 | 0.227 | 0.05 | 0.280 | 0.05 | 0.116 | −0.02 | 0.606 | 0.16 | 0.001 | −0.02 | 0.465 |

| F2F Vic vs. Cy Vic | 0.01 | 0.784 | −0.01 | 0.902 | −0.01 | 0.527 | 0.01 | 0.759 | 0.01 | 0.532 | −0.01 | 0.713 |

| Pub x Med | −0.01 | 0.741 | −0.02 | 0.716 | −0.01 | 0.756 | −0.02 | 0.610 | −0.03 | 0.436 | −0.02 | 0.620 |

| Med x Agg-Blame | 0.04 | 0.161 | −0.01 | 0.980 | −0.02 | 0.576 | 0.04 | 0.406 | −0.01 | 0.863 | 0.04 | 0.251 |

| Pub x Agg-Blame | 0.07 | 0.035 | 0.04 | 0.323 | 0.01 | 0.879 | 0.05 | 0.414 | −0.02 | 0.756 | 0.05 | 0.336 |

| Med x Pub x Agg-Blame | −0.08 | 0.024 | −0.05 | 0.064 | 0.02 | 0.531 | −0.03 | 0.425 | −0.03 | 0.458 | −0.07 | 0.087 |

| Ignoring | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −0.11 | 0.005 | −0.01 | 0.981 | 0.04 | 0.372 | −0.01 | 0.776 | 0.10 | 0.191 | −0.04 | 0.273 |

| Individualism | 0.09 | 0.011 | 0.05 | 0.441 | 0.05 | 0.409 | 0.05 | 0.525 | 0.21 | 0.004 | −0.05 | 0.282 |

| Collectivism | −0.23 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.298 | 0.05 | 0.409 | 0.14 | 0.090 | −0.07 | 0.364 | 0.06 | 0.251 |

| Agg-Blame | 0.09 | 0.084 | 0.08 | 0.158 | 0.15 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.018 | 0.12 | 0.007 |

| Pubic vs. Private | 0.10 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.002 | 0.13 | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.282 | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.001 |

| F2F Vic vs. Cy Vic | −0.06 | 0.005 | −0.07 | 0.001 | −0.01 | 0.589 | −0.01 | 0.867 | −0.01 | 0.570 | 0.01 | 0.980 |

| Pub x Med | −0.03 | 0.318 | 0.01 | 0.620 | −0.07 | 0.098 | −0.04 | 0.146 | −0.04 | 0.145 | −0.04 | 0.154 |

| Med x Agg-Blame | 0.03 | 0.266 | −0.07 | 0.090 | 0.02 | 0.393 | 0.10 | 0.100 | 0.01 | 0.944 | 0.01 | 0.800 |

| Pub x Agg-Blame | 0.02 | 0.584 | −0.03 | 0.527 | −0.05 | 0.507 | −0.05 | 0.182 | −0.02 | 0.542 | −0.04 | 0.501 |

| Med x Pub x Agg-Blame | −0.01 | 0.936 | −0.04 | 0.401 | 0.02 | 0.344 | 0.01 | 0.837 | −0.01 | 0.970 | 0.03 | 0.462 |

| The Self-Blame Attribution | ||||||||||||

| Retaliation | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.10 | 0.001 | −0.09 | 0.139 | −0.25 | 0.001 | 0.10 | 0.094 | 0.16 | 0.002 | 0.14 | 0.001 |

| Individualism | 0.18 | 0.001 | 0.27 | 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.006 | 0.23 | 0.002 | 0.32 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| Collectivism | −0.23 | 0.001 | −0.04 | 0.413 | −0.13 | 0.042 | −0.10 | 0.184 | −0.22 | 0.004 | −0.27 | 0.001 |

| Self-Blame | 0.11 | 0.021 | 0.02 | 0.754 | −0.03 | 0.546 | 0.01 | 0.837 | 0.11 | 0.069 | 0.06 | 0.075 |

| Pubic vs. Private | 0.04 | 0.037 | 0.09 | 0.007 | 0.05 | 0.030 | 0.04 | 0.216 | 0.08 | 0.004 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| F2F Vic vs. Cy Vic | 0.01 | 0.931 | 0.01 | 0.969 | −0.01 | 0.848 | 0.04 | 0.528 | 0.03 | 0.233 | −0.04 | 0.105 |

| Pub x Med | −0.04 | 0.110 | −0.02 | 0.506 | −0.01 | 0.813 | −0.03 | 0.460 | −0.01 | 0.938 | −0.01 | 0.735 |

| Med x Self-Blame | 0.04 | 0.095 | −0.01 | 0.793 | 0.03 | 0.487 | 0.03 | 0.404 | 0.07 | 0.088 | 0.02 | 0.473 |

| Pub x Self-Blame | 0.06 | 0.133 | 0.05 | 0.298 | 0.03 | 0.488 | 0.10 | 0.092 | −0.01 | 0.946 | −0.06 | 0.115 |

| Med x Pub x Self-Blame | −0.04 | 0.170 | −0.05 | 0.201 | −0.05 | 0.194 | −0.05 | 0.444 | −0.03 | 0.572 | 0.02 | 0.635 |

| Social Support | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −0.10 | 0.007 | 0.17 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.001 | −0.18 | 0.001 | −0.12 | 0.022 | −0.09 | 0.013 |

| Individualism | 0.01 | 0.857 | −0.02 | 0.764 | 0.15 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.431 | −0.11 | 0.037 | −0.09 | 0.018 |

| Collectivism | 0.10 | 0.011 | 0.11 | 0.013 | −0.08 | 0.222 | 0.05 | 0.332 | 0.41 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.007 |

| Self−Blame | 0.17 | 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.645 | 0.17 | 0.003 | 0.09 | 0.128 |

| Pubic vs. Private | 0.14 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.16 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.074 | 0.15 | 0.001 |

| F2F Vic vs. Cy Vic | −0.05 | 0.005 | −0.01 | 0.825 | −0.09 | 0.001 | −0.01 | 0.909 | 0.04 | 0.140 | −0.08 | 0.024 |

| Pub x Med | −0.04 | 0.411 | −0.01 | 0.854 | 0.03 | 0.188 | −0.08 | 0.071 | −0.04 | 0.199 | 0.02 | 0.592 |

| Med x Self-Blame | −0.04 | 0.418 | 0.03 | 0.407 | 0.05 | 0.055 | 0.06 | 0.287 | −0.01 | 0.986 | −0.03 | 0.553 |

| Pub x Self-Blame | 0.01 | 0.901 | −0.07 | 0.133 | 0.02 | 0.546 | 0.05 | 0.333 | −0.03 | 0.424 | −0.03 | 0.429 |

| Med x Pub x Self-Blame | −0.01 | 0.679 | 0.01 | 0.925 | −0.04 | 0.231 | −0.04 | 0.558 | 0.03 | 0.587 | −0.02 | 0.711 |

| Helplessness | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −0.14 | 0.003 | 0.12 | 0.037 | 0.05 | 0.333 | −0.13 | 0.001 | −0.27 | 0.001 | −0.09 | 0.047 |

| Individualism | −0.01 | 0.978 | −0.09 | 0.206 | −0.04 | 0.507 | −0.04 | 0.575 | 0.05 | 0.345 | 0.02 | 0.674 |

| Collectivism | −0.01 | 0.950 | 0.04 | 0.637 | −0.01 | 0.801 | 0.03 | 0.680 | −0.05 | 0.479 | −0.01 | 0.729 |

| Self-Blame | 0.08 | 0.094 | 0.12 | 0.077 | 0.21 | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.592 | 0.11 | 0.019 | 0.06 | 0.170 |

| Pubic vs. Private | 0.03 | 0.250 | 0.01 | 0.919 | 0.04 | 0.156 | 0.01 | 0.735 | 0.16 | 0.001 | −0.02 | 0.461 |

| F2F Vic vs. Cy Vic | 0.01 | 0.851 | 0.05 | 0.242 | −0.02 | 0.433 | −0.02 | 0.591 | 0.01 | 0.517 | −0.01 | 0.711 |

| Pub x Med | −0.01 | 0.797 | −0.02 | 0.610 | 0.01 | 0.993 | −0.02 | 0.567 | −0.06 | 0.103 | −0.02 | 0.618 |

| Med x Self-Blame | 0.04 | 0.217 | 0.01 | 0.860 | 0.02 | 0.493 | 0.05 | 0.468 | 0.05 | 0.172 | −0.05 | 0.301 |

| Pub x Self-Blame | 0.05 | 0.121 | −0.04 | 0.534 | −0.08 | 0.085 | 0.04 | 0.515 | −0.01 | 0.828 | −0.01 | 0.967 |

| Med x Pub x Self-Blame | −0.07 | 0.014 | −0.03 | 0.621 | 0.03 | 0.399 | −0.02 | 0.803 | −0.03 | 0.465 | 0.05 | 0.236 |

| Ignoring | ||||||||||||

| Gender | −0.11 | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.714 | 0.02 | 0.698 | −0.02 | 0.626 | 0.09 | 0.193 | −0.03 | 0.368 |

| Individualism | 0.10 | 0.008 | 0.04 | 0.511 | 0.05 | 0.469 | 0.05 | 0.545 | 0.23 | 0.001 | −0.06 | 0.250 |

| Collectivism | −0.21 | 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.233 | 0.05 | 0.303 | 0.15 | 0.051 | −0.09 | 0.295 | 0.07 | 0.196 |

| Self−Blame | 0.14 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.775 | 0.22 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.004 | 0.10 | 0.036 |

| Pubic vs. Private | 0.10 | 0.001 | −0.07 | 0.001 | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.276 | 0.12 | 0.001 | 0.17 | 0.001 |

| F2F Vic vs. Cy Vic | −0.06 | 0.003 | 0.09 | 0.001 | −0.02 | 0.482 | −0.01 | 0.916 | −0.01 | 0.604 | 0.01 | 0.981 |

| Pub x Med | −0.03 | 0.314 | 0.01 | 0.668 | −0.06 | 0.140 | −0.03 | 0.648 | −0.03 | 0.533 | −0.04 | 0.144 |

| Med x Self-Blame | −0.04 | 0.215 | 0.11 | 0.001 | −0.04 | 0.257 | −0.02 | 0.666 | 0.02 | 0.572 | 0.02 | 0.578 |

| Pub x Self-Blame | −0.01 | 0.760 | 0.05 | 0.442 | −0.15 | 0.001 | −0.04 | 0.603 | 0.03 | 0.355 | −0.04 | 0.544 |

| Med x Pub x Self-Blame | 0.02 | 0.612 | −0.10 | 0.022 | 0.09 | 0.018 | 0.03 | 0.630 | −0.05 | 0.117 | 0.01 | 0.726 |

Note. N = 3,432. F2F = Face-to-face; Vic = Victimization; Cy = Cyber; Agg-Blame = Aggressor-Blame Attribution; Pub = Publicity; Med = Medium. Bolded and italicized numbers indicate statistically significant findings, although effect sizes were small

Social Support

Chinese (β = -0.05, p < .01), Czech (β = -0.09, p < .001), and U.S. (β = -0.08, p < .05) adolescents used social support less for private cyber victimization than private face-to-face victimization. In addition, social support was used more for public face-to-face victimization than private face-to-face victimization for Chinese (β = 0.15, p < .001), Cypriot (β = 0.13, p < .001), Czech (β = 0.16, p < .001), Indian (β = 0.12, p < .001), and U.S. (β = 0.15, p < .001) adolescents. The aggressor-blame attribution was related to social support for Czech adolescents (β = 0.10, p < .05). The self-blame attribution was related to social support for Chinese (β = 0.17, p < .001), Cypriot (β = 0.19, p < .001), Czech (β = 0.15, p < .001), and Japanese (β = 0.17, p < .01) adolescents.

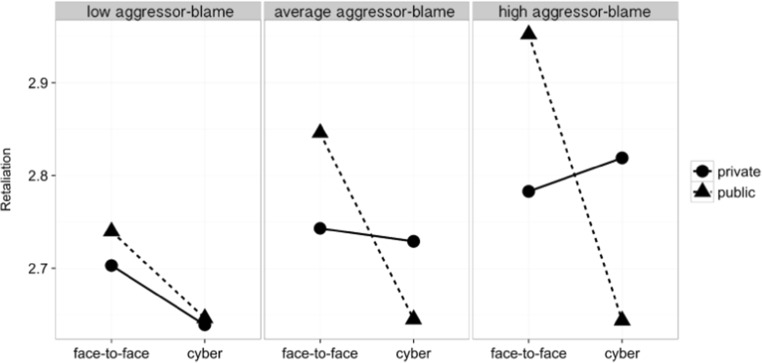

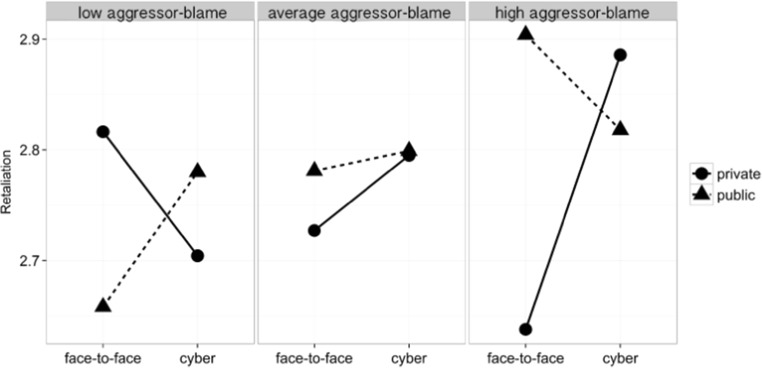

Retaliation

Adolescents from China (β = 0.04, p < .05), Cyprus (β = 0.09, p < .01), the Czech Republic (β = 0.06, p < .05), Japan (β = 0.07, p < .01), and the U.S. (β = 0.12, p < .001) reported that they would use retaliation more for public face-to-face victimization than private face-to-face victimization. The self-blame attribution was related positively to retaliation for Chinese adolescents (β = 0.11, p < .001). Interactions were found between publicity and medium as well as among medium, publicity, and the aggressor-blame attribution for Czech adolescents (see Fig. 1). In addition, for Indian adolescents, an interaction between medium and the aggressor-blame attribution, publicity and the aggressor-blame attribution, and among medium, publicity, and the aggressor-blame attribution were found (see Fig. 2). Findings revealed that retaliation was used more for public face-to-face victimization when Czech and Indian adolescents endorsed more of the aggressor-blame attribution in comparison to private face-to-face victimization and cyber victimization. Retaliation was used more often for private face-to-face victimization and for public cyber victimization when Indian adolescents made less of the aggressor-blame attribution when compared to the other types of victimization. Furthermore, retaliation was used more by Indian adolescents when they endorsed more of the aggressor-blame attribution concerning private cyber victimization than public cyber victimization.

Fig. 1.

Interactions among medium, publicity, and the aggressor-blame attribution for retaliation among Czech adolescents (n = 537)

Fig. 2.

Interactions among medium, publicity, and the aggressor-blame attribution for retaliation among Indian adolescents (n = 480)

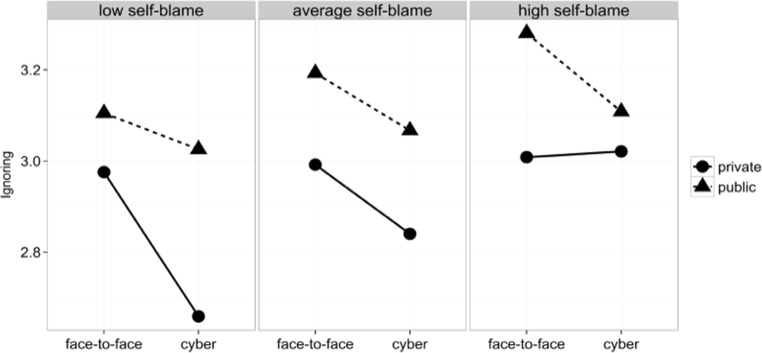

Ignoring

Ignoring was reported as a coping strategy more often for public face-to-face victimization than for private face-to-face victimization among Chinese (β = 0.10, p < .001), Cypriot (β = 0.09, p < .01), Czech (β = 0.12, p < .001), Indian (β = 0.13, p < .001), Japanese (β = 0.12, p < .01), and U.S. (β = 0.17, p < .001) adolescents. Furthermore, ignoring was used less often for private cyber victimization than private face-to-face victimization among Chinese (β = -0.06, p < .01) and Cypriot (β = -0.09, p < .001) adolescents. The aggressor-blame attribution was related positively to ignoring among Indian (β = 0.15, p < .001), Japanese (β = 0.14, p < .05), and U.S. (β = 0.12, p < .001) adolescents. In addition, the self-blame attribution was associated positively with ignoring among Chinese (β = 0.14, p < .01), Czech (β = 0.22, p < .001), Indian (β = 0.17, p < .001), Japanese (β = 0.011, p < .01), and U.S. (β = 0.10, p < .05) adolescents.

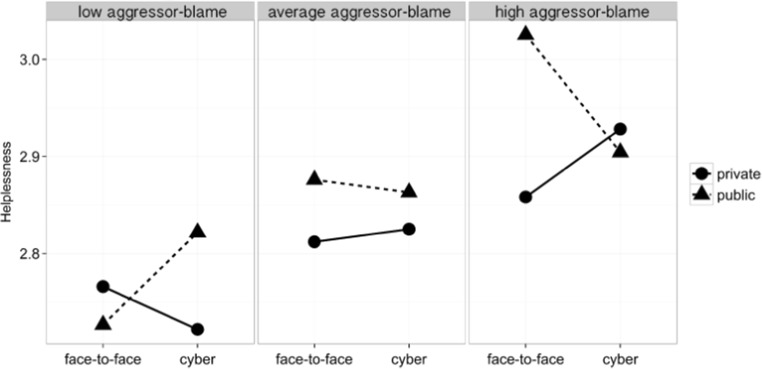

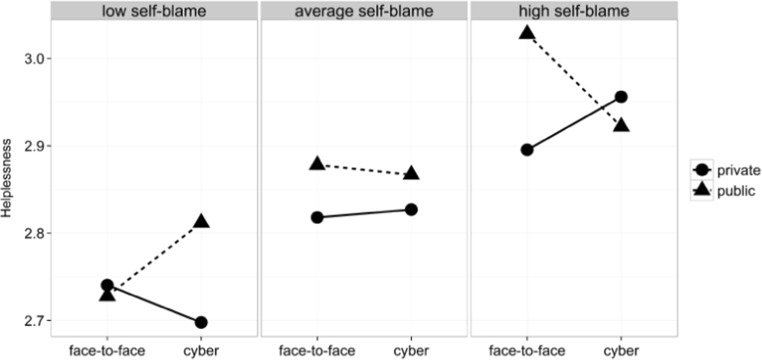

Interactions for Cypriot adolescents were found for medium and the self-blame attribution as well as among publicity, medium, and the self-blame attribution (see Fig. 3). The interactions between publicity and the self-blame attribution and among publicity, medium, and the self-blame attribution were significant for Czech adolescents (see Fig. 4). In particular, ignoring was used more for public face-to-face victimization when adolescents employed the self-blame attribution in comparison to private face-to-face victimization and cyber victimization among Cypriot and Czech adolescents.

Fig. 3.

Interactions among medium, publicity, and the self-blame attribution for ignoring among Cypriot adolescents (n = 470)

Fig. 4.

Interactions among medium, publicity, and self-blame attribution for ignoring among Czech adolescents (n = 537)

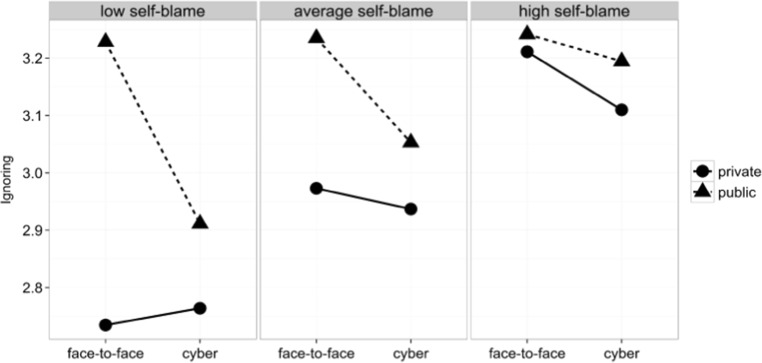

Helplessness

Helplessness was reported more for public victimization than private victimization among Japanese (β = 0.16, p < .001) adolescents. The aggressor-blame attribution was related negatively to helplessness among Indian (β = -0.17, p < .01) adolescents, while it was associated positively with helplessness among Japanese (β = 0.18, p < .001) adolescents. The self-blame attribution was related positively to helplessness among Czech (β = 0.21, p < .001) and Japanese (β = 0.11, p < .05) adolescents.

Interactions were found as well. In particular, there were interactions between publicity and the aggressor-blame attribution, among publicity, medium, and the aggressor-blame attribution, and among publicity, medium, and the self-blame attribution for Chinese adolescents. When Chinese adolescents used less of the aggressor-blame attribution and the self-blame attribution, they used helplessness more for public cyber victimization than for private cyber victimization and face-to-face victimization (see Fig. 5 for the aggressor-blame attribution and Fig. 6 for the self-blame attribution). On the other hand, helplessness was used more often for public face-to-face victimization than private face-to-face victimization and cyber victimization when Chinese adolescents used more of the aggressor-blame attribution and the self-blame attribution.

Fig. 5.

Interactions among medium, publicity, and the aggressor-blame attribution for helplessness among Chinese adolescents (n = 673)

Fig. 6.

Interactions among medium, publicity, and the self-blame attribution for helplessness among Chinese adolescents (n = 673)

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine how publicity (private, public), medium (face-to-face, cyber), and adolescents’ attributions influence their coping strategies for hypothetical victimization scenarios, after controlling for individualism and collectivism, and gender. These differences were examined among adolescents from China, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, India, Japan, and the U.S. Overall, the findings indicated differences in the impact of the self-blame attribution and the aggressor-blame attribution on adolescents’ coping strategies based on the publicity and medium of victimization. For Indian and Czech adolescents, they used retaliation for face-to-face public victimization when they made more of the aggressor-blame attribution. In addition, helplessness was reported as a coping strategy when Chinese adolescents made the aggressor-blame attribution and the self-blame attribution. Similar patterns were found for Cypriot adolescents, the self-blame attribution, and ignoring. The aggressor-blame attribution involves blaming bullying or aggression on the perpetrator’s psychological characteristics (Yeager et al. 2013). The findings of the present study are consistent with various studies linking the aggressor-blame attribution to aggressive behaviors, like face-to-face bullying and cyberbullying (Boxer and Tisak 2003; Coie and Pennington 1976; Shelley and Craig 2009; Troop-Gordon and Ladd 2005; Visconti et al. 2013; Yeager et al. 2013). Adolescents might feel like they are unable to avoid peer victimization, especially if they believe that the aggressor has some negative psychological characteristics that promote further aggressive behaviors. The self-blame attribution involves attributing peer victimization to oneself, which might lead some adolescents to use non-aggressive coping strategies, although no research has focused on this topic so far (Graham and Juvonen 1998; Mathieson et al. 2011; Troop-Gordon and Ladd 2005). Distancing coping strategies are typically associated with the self-blame attribution (Shelley and Craig 2009; Visconti et al. 2013). Thus, finding that the self-blame attribution influenced the coping strategies of ignoring is consistent with the literature.

Little attention has been given to the influence of adolescents’ attributions on their coping strategies to deal with public and private face-to-face victimization and cyber victimization. The present study addressed this gap in the literature. Findings from the present study underscore the significance of examining multiple contexts, particularly medium, publicity, and culture, when investigating adolescents’ attributions and coping strategies for victimization. It is important to understand adolescents’ attributions and coping strategies for victimization as such experiences are related to short-term and long-term adjustment difficulties (Hampel and Petermann 2005). Such a consideration is important as these adjustment difficulties might be greater in one social context vs. another. Follow-up research should investigate such a proposal, especially with consideration to how adolescents’ attributions and coping strategies in different contexts could influence adjustment difficulties.

Further attention should be given to developing prevention and intervention strategies based on the various contexts of victimization. Additional attention on this topic is especially important as these strategies might vary based on country of origin as well. This consideration is incredibly important as the findings from this study revealed some unique patterns based on country of origin. For Chinese adolescents, the self-blame attribution was associated with the coping strategy of retaliation. In the literature, the self-blame attribution is not typically linked to retaliatory behavior (Boxer and Tisak 2003; Coie and Pennington 1976; Troop-Gordon and Ladd 2005; Yeager et al. 2013). A potential explanation for the difference between the results concerning Chinese adolescents and the literature might be that previous studies have focused on Western samples. Research has indicated that adolescents from Eastern cultures utilize more of the self-blame attribution when compared to adolescents from Western cultures, who typically use more of the aggressor-blame attribution (Crystal 2000; Hui 2001). Therefore, Chinese adolescents might be more likely to make the self-blame attribution, regardless of its association with revengeful behaviors. Another unique finding was that Indian adolescents used retaliation for private cyber victimization when they made more of the aggressor-blame attribution. This result contrasts with the overall findings from the study that attributions typically impacted coping strategies more for face-to-face and public forms of victimization. It is difficult to explain why such differences might be found, due to limited research attention on this topic. Taken together, these findings have potential implications for culturally-sensitive intervention and prevention programs that are designed to reduce adolescents’ involvement in face-to-face bullying and cyberbullying in various contexts across different countries.

In the present research, we focused on early adolescents. Such a focus makes it difficult to develop conclusions about age-related differences in the impact of attributions on adolescents’ coping strategies, and how publicity and medium might influence these associations. Follow-up research should be conducted on these topics to understand how attributions relate to adolescents’ coping strategies for peer victimization based on context and medium. This research should also expand on the attributions and coping strategies used for public and private face-to-face and cyber victimization. In particular, the present study focused on the aggressor-blame attribution and the self-blame attribution, although adolescents might utilize a variety of other attributions (Wright et al. 2014). In addition, this study used retaliation, social support, helplessness, and ignoring as coping strategies, and additional research should be conducted with other coping strategies as well. Adolescents provided their attributions and coping strategies for hypothetical peer victimization situations. Although hypothetical peer victimization situations have been examined in other studies, follow-up research should focus on their attributions and coping strategies for their actual experiences with public and private face-to-face and cyber victimization. Another aim of future research is to understand how these attributions and coping strategies influence adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment difficulties, like depression, anxiety, and loneliness. We also focused on the context of publicity in the current research. There are a variety of other contexts of peer victimization, such as anonymous and non-anonymous forms of victimization. Therefore, follow-up research should consider other contexts of peer victimization. The present research did not consider gender differences in attributions and coping strategies, although future research should focus on such differences. Adolescents were the focus of our research, but more research attention is needed to focus on young children and their attributions and coping strategies for face-to-face and cyber victimization.

The findings from the present study underscore the importance of investigation medium (face-to-face, cyber) and publicity (public, private) when examining how adolescents’ attributions influence their coping strategies for peer victimization. The findings from the present study revealed that adolescents from some countries have differential patterns of these associations. Therefore, prevention and intervention programs should be designed with consideration to the context of peer victimization and country of origin.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest in the conduction of this research.

References

- Ang RP, Goh DH. Cyberbullying among adolescents: the role of affective and cognitive empathy, and gender. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2010;41(4):387–397. doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji MS, Chakrabarti D. Student interactions in online discussion forum: empirical research from ‘Media Richness Theory’ perspective. Journal of Interactive Online Learning. 2010;9(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Tisak M. Adolescents’ attributions about aggression: an initial investigation. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26(5):559–573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(03)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Wojslawowicz JC, Rubin KH, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C. Social information processing and coping strategies of shy/withdrawn and aggressive children: does friendship matter? Child Development. 2006;77(2):371–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, French DC. Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:591–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Pennington BF. Children’s perceptions of deviance and disorder. Child Development. 1976;47(2):407–413. doi: 10.2307/1128795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal DS. Concepts of deviance and disturbance in children and adolescents: a comparison between the United States and Japan. International Journal of Psychology. 2000;35(5):207–218. doi: 10.1080/00207590050171148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

- Essau CA, Trommsdorff G. Coping with university-related problems: a cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1996;27(3):315–328. doi: 10.1177/0022022196273004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flammer A, Ito T, Luthi R, Plaschy N, Reber R, Zurbriggen L, Sugimine H. Coping with control-failure in Japanese and Swiss adolescents. Swiss Journal of Psychology. 1995;54:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, Lemerise EA. The roles of behavioral adjustment and conceptions of peers and emotions in preschool children’s peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:57–71. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, S. N. (2005). Growing and learning in the Greek Cypriot family context. In A. Columbus (Ed.), Advances in psychology research (pp. 121–141). Hauppauge, NY: NOVA Science Publishers.

- Graham S, Juvonen J. Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: an attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:587–599. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel P, Petermann F. Age and gender effects on coping in children and adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2005;34(2):73–83. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-3207-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J. W. (2012). School climate 2.0: Preventing cyberbullying and sexting one classroom at a time. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Hox, J. (2010). Multilevel analysis. Techniques and application. New York: Routledge.

- Hui EKP. Hong Kong students’ and teachers beliefs on students’ concerns and their causal explanation. Educational Research. 2001;43(3):279–284. doi: 10.1080/00131880110081044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, Crick NR, Hamaguchi Y. The association of relational and physical victimization with hostile attribution bias, emotional distress, and depressive symptoms: a cross-cultural study. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2013;16:260–270. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam AG, Zane NWS. Ethnic differences in coping with interpersonal stressors: a test of self-construals as cultural mediators. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2004;35(4):446–459. doi: 10.1177/0022022104266108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

- Li Y, Wang M, Wang C, Shi J. Individualism, collectivism, and Chinese adolescents’ aggression: intracultural variations. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:187–194. doi: 10.1002/ab.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsella, A. J., & Dash-Scheuer, A. (1988). Coping, culture, and health human development: a research and conceptual overview. In P. R. Dasen, J. w. Berry & N. Sartorius (Eds.), Health and cross-cultural psychology: Towards applications (pp. 162–178). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Mathieson LC, Murray-Close D, Crick NR, Woods KE, Zimmer-Gembeck M, Geiger TC, Morales JR. Hostile intent attributions and relational aggression: the moderating roles of emotional sensitivity, gender, and victimization. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(7):977–987. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9515-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, D., & Juang, L. (2004). Culture and psychology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Ortega R, Elipe P, Mora-Merchan JA, Calmaestra J, Vega E. The emotional impact on victims of traditional bullying and cyberbullying: a study of Spanish adolescents. Journal of Psychology. 2009;217(4):197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Folkman S. Meaning in the context of stress and coping. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1(2):115–144. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.1.2.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perren S, Corcoran L, Cowie H, Dehue F, Garcia DJ, Mc Guckin C, Vollink T. Tackling cyberbullying: review of empirical evidence regarding successful responses by students, parents, and schools. International Journal of Conflict and Violence. 2012;6(2):283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Pornari CD, Wood J. Peer and cyber aggression in secondary school students: the role of moral disengagement, hostile attribution bias, and outcome expectancies. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36(2):81–94. doi: 10.1002/ab.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Cheah CSL, Guyer AE. Peer victimization, cue interpretation, and internalizing symptoms: preliminary concurrent and longitudinal findings for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:11–24. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runions K, Shapka J, Dooley J, Modecki K. Cyber-aggression and victimization and social information processing: integrating the medium and the message. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3(1):9–26. doi: 10.1037/a0030511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapka, J. (2012). Cyberbullying and bullying are not the same: UBC research. Retrieved from: http://www.publicaffairs.ubc.ca/2012/04/13/cyberbullying-and-bullying-are-not-the-same-ubc-research/.

- Shelley D, Craig WM. Attributions and coping styles in reducing victimization. Canadian Journal of School Psychology. 2009;25(1):84–100. doi: 10.1177/0829573509357067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Cowie H, Olafsson RF, Liefooghe APD. Definitions of bullying: a comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a fourteen–country international comparison. Child Development. 2002;73:1119–1133. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Fisher S, Russell S, Tippett N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(4):376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, T., & Bosker, R. (2012). Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. London: Sage.

- Sticca F, Perren S. Is cyberbullying worse than traditional bullying? Examining the differential roles of medium, publicity, and anonymity for the perceived severity of bullying. Journal of Youth & Adolescence. 2013;42(5):739–750. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9867-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry DJ. Determinants of coping: the role of stable and situational factors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66(5):895–910. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.66.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga RS. Following you home from school: a critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010;26:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2009.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon W, Ladd GW. Trajectories of peer victimization and perceptions of the self and schoolmates: precursors to internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2005;76:1072–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma J. Situational preference for different types of individualism-collectivism. Psychology Developing Societies. 2001;13(2):221–241. doi: 10.1177/097133360101300206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Visconti KJ, Sechler CM, Kochenderfer-Ladd B. Coping with peer victimization: the role of children’s attributions. School Psychology Quarterly. 2013;28(2):122–140. doi: 10.1037/spq0000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MF, Li Y, Shi J. Chinese adolescents’ social status goals: associations with behaviors and attributions for relational aggression. Youth & Society. 2014;46(4):566–588. doi: 10.1177/0044118X12448800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MF, Yanagida T, Sevcikova A, Aoyama I, Dedkova L, Machackova H, Li Z, Kamble SV, Bayraktar F, Soudi S, Lei L, Shu C. Differences in coping strategies for public and private face-to-face and cyber victimization among adolescents in six countries. International Journal of Developmental Science. 2017;48(8):1216–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Miu A, Powers J, Dweck CS. Implicit theories of personality and attributions of hostile intent: a meta-analysis, an experiment, and a longitudinal intervention. Child Development. 2013;84(5):1651–1667. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh K. Mediating effects of negative emotions in parent-child conflict on adolescent problem behavior. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;14(4):236–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2011.01350.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]