Abstract

The aim of this study was to test a model to better explain which factors are linked to the development of internalized and externalized problems in adolescents experiencing death through structural equation model. Internalizing problems were predicted by low self-esteem, high PTSD symptomatology and by being a female, whereas externalizing problems were predicted by low self-esteem, by the experience of the loss as central in their own life and by being a male. Our results pointed out the potential importance of controlling this factors in order to provide focused interventions for adolescents after the death of a significant one.

Keywords: Adolescent, Death, Bereavement, Internalization problems, Externalization problems

Loss and bereavement of a loved one is one of the most stressful life events that children and adolescents can experience (Alisic et al. 2008; Breslau et al. 2004). These events have been widely considered and included in different models of psychopathology (Bowlby 1969; Stroebe et al. 2005) and in different studies they were found to be risk factors for developing Mental disorder in childhood, adolescence and adulthood (Melhem et al. 2007; Prigerson et al. 2009). Adolescence is a time of transition in which several changes need to be addressed such as the restructuring of physical identity, the emancipation from the family to open up to new forms of sociability, the achievement of new levels of self-reflection and the expansion of the areas of interest and life goals (Adams and Berzonsky 2008; Coleman and Hendry 1990). In addressing these changes teenagers may develop areas of vulnerability, especially if they had to cope with potentially traumatic life events (Ionio et al. 2013; Oransky et al. 2013). Some studies pointed out that the difficulties of psychological adaptation, typical of the adolescence, after a negative and traumatic event could lead to a critical development of a coherent self (Habermas and Bluck 2000) and a definite identity (Erikson 1963; Ogle et al. 2013).

Several reviews and studies highlighted that bereavement and loss are related to depressive symptoms, withdrawal and academic problems during adolescence (Dowdney 2000; Lutzke et al. 1997; Mash et al. 2014; Melhem et al. 2004). Furthermore, other studies have revealed that bereaved adolescents generally exhibit acute grief reactions, hostility, tension, problems related to self-esteem, sleep and behavioral problems (Kranzler et al. 1990; Mash et al. 2014; Ursano 2014). Other studies have found that bereaved children have higher levels of aggressive and delinquent behavior (Draper and Hancock 2011; Kranzler et al. 1990). Different investigations have shown between death of a love one and clinical levels of internalizing and externalizing problems (Gersten et al. 1991; Draper and Hancock 2011; Mash et al. 2014). For example, Worden and Silverman (1996) pointed out that 21% of children and adolescents who have experienced bereavement two years prior to the study scored above the clinical threshold or internalizing or externalizing problems measured by Child Behavior Checklis 4–18 (Achenbach 1991), while only 3% of children and adolescent in the control sample was above this cut-off. Furthermore, Stikkelbroek et al. (2016) found that bereaved adolescents developed more internalizing problems than non-bereaved adolescents: the presence of internalizing problems in bereaved adolescents was four times higher in their non-bereaved peers.

Although different studies highlighted that major life events such as loss and bereavement of a loved one can have significant negative outcomes on child and adolescent wellbeing and mental health, to our knowledge still few studies have focused on factors that lead to these outcomes (Boelen and Spuij 2013; Dowdney 2000; Grant et al. 2003; Sandler et al. 2010; Stikkelbroek et al. 2016; Wolchik et al. 2006). Some studies have shown that among these factors can be identified self-esteem (Haine et al. 2003; Mack 2001; Wolchik et al. 2006). Different authors pointed out that self-esteem plays an important role in the development of internalizing and externalizing problems after the death of a loved one (Haine et al. 2003; Sandler et al. 2010; Trzesniewski et al. 2006; Wolchik et al. 2006). Luecken and Roubinov (2012) pointed out that low self-system beliefs, including self-esteem, self-efficacy and social relatedness could be important risk factors for developing mental health problems. Other studies pointed out that the degree to which bereaved individuals experience their loss as central, as a core topic for identity and for the attribution of meaning to life experience is related to emotional problems following loss (Boelen 2009; Field 2003. People that perceived high levels of centrality of the loss-event are impaired in the resolution of grief, as they are not able to have access to memory information related to the lost person that is necessary for the revision of views of the self and future (Boelen et al. 2003, 2006). Another important factor related both to the loss of a loved person and to the experience of their loss as a central event in life is the presence of PTSD symptoms (Berntsen and Rubin 2006; 2007). Boelen and Spuij (2013) pointed out that PTSD symptoms after the loss of a loved person play an important role in internalized problems in children and adolescents. Finally, in regards to the role of gender, previous studies pointed out that during adolescence, gender is another risk factor for increased depressive symptoms, with females suffering twice as much as males (Thapar et al. 2012), nevertheless, research on gender as a risk factor for problems in bereaved adolescents are so far inconclusive. In fact, this study, showed that the bereaved child’s gender did not affect the risk for future internalizing and externalizing problems (Gray et al. 2011; Melhem et al. 2008; Weller and Weller 1991; Raveis et al. 1999).

However, a limitation of these studies is that our samples were composed primarily of adolescents who have lost a parent (Silverman and Worden 1992) or friend (Melhem et al. 2004). For this reason, the main aim of the present study was to test a model to better explain which factors are linked to the development of internalized and externalized problems among adolescents who experienced loss and grief. In agreement with previous studies that suggested that internalized and externalized problems are associated with other deaths, more common than parents’ or friends’ death, such as of grandparents we decided to take into account different types of loss and grief (Harrison and Harrington 2001).

We tested the hypothesis according to which any kind of death may be considered as a traumatic event, which may determine specific negative impacts on the psychological, emotional and affective adolescent development, that need to be processed and investigated.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from 747 adolescents, 476 males (63.7%) and 271 females (36.3%), aged between 14 and 21 years (mean age = 16:45; DS = 1.57), who were recruited in different high schools in Northern Italy. With the permission of the headmaster and the teachers they were approached at school during lessons, by a trained research psychologist, who, after a brief meeting conversation, introduced them the research aims.

We asked to them to write about a negative experience they lived in person. They were left free to describe what they want. They were also asked to describe the characteristics of the event and the impact that this event had in the personal history. From the narratives, we selected a convenience sample of those adolescent that experienced a loss. Data were available from 140 adolescents, composed of 80 males (57.1%) and 60 females (42.9%), aged 14 to 21 years (M = 16.56, SD = 1.51). Of the total group of participants, almost all (n = 132; 97.1%) had the Italian nationality.

As for parents’ occupations, in our sample 12.6% of mothers were artisans and workers, 29.8% were office workers, 5.9% worked in human health and services, 28.3% were housewives, 10.4% worked in educational services, 3.0% were manager, 6.7% worked in retail, and 4.5% were freelance; as regards fathers in our sample 42.2% were artisans and workers, 19.5% were office workers, 3.2% worked in human health and services, 4.7% were retired, 2.3% worked in educational services, 6.3% were manager, 11.8% worked in shopping activities, 4.5% were freelance, 1.6% were engineers and 0.8% were policeman. No data were collected on socio-economic status.

In our sample, 121 adolescents (86.4%) experienced the death of persons belonging to their extended family, friends and acquaintances, while 19 adolescents (13.6%) had experienced the loss of a nuclear family member. They have experienced the event death at a mean age of 12,7 years old (SD = 4.3) and since this event have passed an average of 3.8 years (SD = 4.2).

Measures

Demographic and loss-related variables were collected from adolescents’ narratives. They were left free to tell their experience, without limit in the length of the writing and in the absence of specific requests. Furthermore, every participant filled out the following questionnaires:

Youth Self Report for ages 11–18 (YSR; Achenbach 1991)

The YSR is a self-report questionnaire divided in two parts 1) Competencies and 2) Problems. In the present study, only the problem scale was used. It consists of 112 items, covering different symptoms/behaviours each to be rated on a three-point scale (2 “the symptom is present most of the time”, 1 “the symptom is present some of the time”, 0 “absence of symptom or problem behaviour”). The YSR total problem scale can be divided into two sub dimensions related to Internalising and Externalising problems. Withdrawn, Somatic complaints and Anxious/Depressed together constitute the ‘internalising’ dimension, whereas Delinquent and Aggressive behaviours together constitute the ‘externalising’ dimension. Internal consistency was adequate for most syndrome scales and good for the Internalising and Externalising dimensions (Ivarsson et al. 2002). For the present study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the internalizing problems dimension was .85 .87 for the externalizing problems dimension was.87 and .91 for the total.

Rosenberg Self - Esteem Scale (RSE; Rosenberg 1965)

The RSE is a widely used self-report instrument for evaluating individual self-esteem, was investigated using item response theory. It is a 10-item scale that measures global self-worth by measuring both positive and negative feelings about the self. The scale is believed to be one-dimensional. All items are answered using a 4-point Likert scale format ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree (Rosenberg 1965). For the present study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability was .65.

Centrality of Event Scale (CES; Berntsen and Rubin 2006)

The CES was used to measure the extent to which a traumatic event is central to one’s everyday inferences (“This event has become a reference point for the way I understand myself and the world”), life-story (“This event permanently changed my life”), and identity (“I feel that this event has become part of my identity”). It is composed of 22 items rated on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from totally disagree to totally agree. For the current study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability was .94.

Impact of Event Scale Revised (IES-R; Weiss and Marmar 1997; Italian version by Pietrantonio, De Gennaro, Di Paolo, and Solano, 2003)

The IES-R explores feelings immediately after a potential traumatic event, in our case the loss of a loved one. It is composed of 22 items divided into 3 clusters rated on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all), to 4 (extremely) that measure the presence of posttraumatic stress symptomatology: 8 items regarding symptoms of avoidance (avoidance of feelings, situations, memories; e.g. “I tried not to think about it”), 7 items regarding symptoms of intrusion (flashbacks, nightmares, images; e.g. “I had dreams about it”), and 7 items regarding symptoms of hyperarousal (fear, irritability, hypervigilance, and difficulties in concentration; e.g. “I felt irritable and angry”). There is also another scale that shows the total score. For the present study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the subscales were .68 (avoidance) .87 (intrusion) .72 (hyperarousal) and .87 for the total.

Procedures

Participants were recruited through a convenience sampling, including adolescents that agreed to participate in the research. They were asked to describe a negative experience they lived in person, the characteristics of the event and the impact that this event had in their life. After that, they were given 20 min to complete all self-report questionnaires.

Ethical approval was gained through the University research ethics committee, which required informed consent from the parents of each participant. Therefore, the headmaster, teachers, and parents of the adolescents provided permission for participation. Informed consent for the protection of privacy (Law No. 196 of 2003) was a prerequisite for participation in the study.

Statistical Analyses

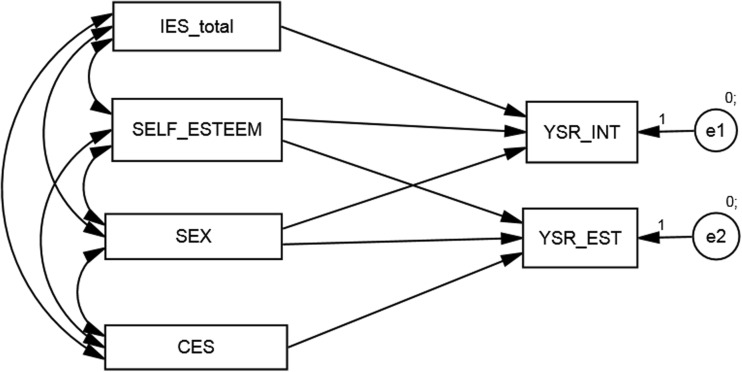

In the present study, the pattern of relationships depicted in the model was tested by structural equation modelling using AMOS 6.0 software (Arbuckle 2003). Goodness-of-fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Conventional guidelines were followed whereby fit is considered adequate if CFI values are >0.90 and RMSEA is <0.08. The model (Fig. 1) had goodness-of-fit indexes as follows: χ2 = 5.022, p = .170, χ2/df = 3; CFI = .988, RMSEA = .07. Table 1 shows the results of the model analyses.

Fig. 1.

Model to test

Table 1.

Results of the model analyses

| Parameter | Standardized |

|---|---|

| Self-esteem → YSR-int | −10,35*** |

| Self-esteem → YSR-est | −3,52* |

| Gender → YSR-int | 2,18* |

| Gender → YSR-est | −3,49** |

| IES → YSR-int | ,99*** |

Results

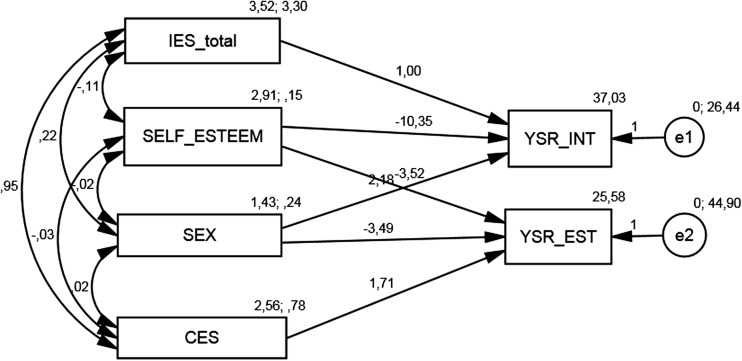

Table 2 show the model coefficients and the variance explained for the outcome variables. Structural coefficients from the completely standardized solution are displayed in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Model coefficients and variance explained for the outcome variables

| Variable | Estimates (%) |

|---|---|

| YSR-int | 37.03 |

| YSR-est | 25.28 |

Fig. 2.

Model showing the structural coefficients from the completely standardized solution

As can be seen in Fig. 2, most of the hypothesized paths in the model were significant. Low level of self-esteem (β = −10.35), high level of PTSD symptomatology (β = .99) and being a female (β = 2.18) increased the presence of internalizing problems in adolescent after the loss of a loved one. Furthermore, low self-esteem (β = −3.52), the perception of high levels of centrality of the loss-event (β = 1.71) and being a male (β = −3.49) increased the presence of externalizing problems in adolescent after the loss of a loved one.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to test a model to better explain which factor such as self-esteem, centrality of event, PTSD symptoms, and gender are linked to the development of internalized and externalized problems among adolescents who experienced different types of loss and grief.

Adolescence is a time of transition in which several changes need to be addressed (Adams and Berzonsky 2008; Coleman and Hendry 1990). During this transition, teenagers may develop areas of vulnerability, especially if they have had to cope with potentially traumatic life events (Oransky et al. 2013; Ionio et al. 2013). For this reason, it is important to monitor those adolescents that faced a stressful or traumatic event, both to identify as soon as possible the presence of characteristics that may be considered as risk factors that lead to future difficulties and to empower those protective factors that could lead them to a good adaptation, despite adverse life events.

Previous investigators identified multiple risks factors that lead to significant negative outcomes after a loss: low self-esteem, the degree to which bereaved individuals experience their loss as central, the presence of high level of PTSD symptoms and gender (Berntsen and Rubin 2006; 2007; Boelen 2009; Boelen and Spuij 2013; Field 2003; Haine et al. 2003; Sandler et al. 2010; Wolchik et al. 2006). According to these previous studies, we tested a model in which we considered these factors linked to internalizing and externalizing problems that may develop during adolescence.

Internalizing problems such as withdrawal, somatic complaints, anxiety, and depression, that are common in adolescents that experienced loss and grief (Dowdney 2000; Lutzke et al. 1997 were predicted simultaneously by low levels of self-esteem and by high level of PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, our model pointed out that girls are more at risk to develop this type of problem than boys. These results support previous findings that underlined that females suffering twice as much as male (Johansen et al. 2007). Externalizing problems such as delinquent and aggressive behaviours were predicted simultaneously by low levels of self-esteem and by the experience of the loss as central in their own life. Furthermore, according to studies on population of healthy adolescence, this model pointed out that males are more at risk to develop this type of problems than female (Stinson et al. 1992).

Moreover, our findings suggest that self-esteem plays an important role in a population of adolescents that have experienced the loss of a loved one. Similarly, previous studies showed that adolescents with low self-esteem were at risk for developing internalizing and externalizing problems, poor mental outcomes, delinquent and aggressive behaviours. In addition, our study examined the associations between PTSD symptoms and indices of mental health problems as internalizing and externalizing problems. In agreement with Boelen and Spuij’s findings (Boelen and Spuij 2013) our results pointed out that internalizing problems, but not externalizing problems were predicted by PTSD symptoms.

Regarding the predictive role of the perception of a traumatic event as central in life-and identity on externalizing problems, our findings are consistent with those researches that pointed out the negative consequences of construing a potentially traumatic event as central to one’s identity (Berntsen and Rubin 2006). While previous studies have indicated a relationship between centrality of loss and internalizing problems such as depression (Boelen 2009; Boals and Schuettler 2011), our findings indicate that the centrality of the loss play an important role in predicting externalize problems.

Finally, we also considered gender as risk factors that could influence adolescents’ outcomes after a loss. Our data suggested that that girls are at risk of developing internalizing problems over time after the loss of a loved one, finding agrees with previous longitudinal studies that heightened on the one hand vulnerability for girls after parental death (Reinherz et al. 1999; Schmiege et al. 2006) and on the other the presence of higher level of anger, aggression and externalizing symptoms in boys (Qouta et al. 2005; Stinson et al. 1992).

In conclusion, our data showed that self-esteem, centrality of event, PTSD symptoms, and gender are important factors linked to the development of internalized and externalized problems among adolescents who experienced different types of loss and grief. For this reason, it will be important to consider these variables to support those adolescents that are more fragile and more at risk after loss.

Limitations and Future Direction

Due to the composition of our sample, we were not able to compare different types of loss. Furthermore, we did not detect if the participants have benefited from psychological support or have experienced other traumatic events. In addition, the group has a large variability of age, and then at different times of the development of their own identity. Finally, we didn’t take in consideration other types of variables such as personal and family history to mental health disorders that could influence the presence of internalizing and externalizing problems, and faith or spirituality that, as Wortmann and Park (2008) suggested, they may be important factors that could mediate the relationship between loss and future and difficulties.

Starting from these limitation, future studies could compare different kinds of grief, consider the age at the time of loss and the years that have passed, the expectedness of death, the presence of further traumatic events as risk factors, and the role of faith and spirituality as protective factors after the loss of a loved one.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

The study have been approved by the University Ethics Committee and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All parents gave their informed consent for their children prior to their inclusion in the study.

References

- Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile (p. 288). Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont.

- Adams, G. R., & Berzonsky, M. (Eds.). (2008). Blackwell handbook of adolescence (Vol. 8). Wiley.

- Alisic E, van der Schoot TA, van Ginkel JR, Kleber RJ. Trauma exposure in primary school children: Who is at risk? Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 2008;1(3):263–269. doi: 10.1080/19361520802279075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, J. (2003). Amos 5.0 update to the Amos user’s guide. Marketing Department, SPSS incorporated.

- Berntsen D, Rubin DC. The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one's identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(2):219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2007). When a trauma becomes a key to identity: Enhanced integration of trauma memories predicts posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21(4), 417–431.

- Boals A, Schuettler D. A double-edged sword: Event centrality, PTSD and posttraumatic growth. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2011;25(5):817–822. doi: 10.1002/acp.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA. The centrality of a loss and its role in emotional problems among bereaved people. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(7):616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, Spuij M. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in bereaved children and adolescents: Factor structure and correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41(7):1097–1108. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9748-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, van den Bout J, van den Hout MA. The role of cognitive variables in psychological functioning after the death of a first degree relative. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41(10):1123–1136. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, van den Bout J, van den Hout MA. Negative cognitions and avoidance in emotional problems after bereavement: A prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(11):1657–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss. Nueva York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Lucia VC, Anthony JC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: A study of youths in urban America. Journal of Urban Health. 2004;81(4):530–544. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J. C., & Hendry, L. (1990). La natura dell’adolescenza, il Mulino.

- Dowdney L. Annotation: Childhood bereavement following parental death. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41(07):819–830. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper A, Hancock M. Childhood parental bereavement: The risk of vulnerability to delinquency and factors that compromise resilience. Mortality. 2011;16(4):285–306. doi: 10.1080/13576275.2011.613266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. The landmark work on the social significance of childhood. New York: Norton; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Field, N. P., Gal-Oz, E., & Bonanno, G. A. (2003). Continuing bonds and adjustment at 5 years after the death of a spouse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 110. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gersten JC, Beals J, Kallgren CA. Epidemiology and preventive interventions: Parental death in childhood as a case example. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19(4):481–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00937988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Halpert JA. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(3):447. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray LB, Weller RA, Fristad M, Weller EB. Depression in children and adolescents two months after the death of a parent. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;135(1):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, Bluck S. Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(5):748. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine RA, Ayers TS, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Weyer JL. Locus of control and self-esteem as stress-moderators or stress-mediators in parentally bereaved children. Death Studies. 2003;27(7):619–640. doi: 10.1080/07481180302894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, L., & Harrington, R. (2001). Adolescents' bereavement experiences. Prevalence, association with depressive symptoms, and use of services. Journal of adolescence, 24(2), 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ionio C, Olivari MG, Confalonieri E. Eventi traumatici in adolescenza: Risposte psicologiche e comportamentali. Maltrattamento e abuso all’infanzia. 2013;15(2):87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ivarsson T, Gillberg C, Arvidsson T, Broberg AG. The youth self-report (YSR) and the depression self-rating scale (DSRS) as measures of depression and suicidality among adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;11(1):31–37. doi: 10.1007/s007870200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen VA, Wahl AK, Eilertsen DE, Weisaeth L. Prevalence and predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in physically injured victims of non-domestic violence. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42(7):583–593. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranzler EM, Shaffer D, Wasserman G, Davies M. Early childhood bereavement. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29(4):513–520. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecken LJ, Roubinov DS. Pathways to lifespan health following childhood parental death. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2012;6(3):243–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzke, J. R., Ayers, T. S., Sandler, I. N., & Barr, A. (1997). Risks and interventions for the parentally bereaved child. In Handbook of children’s coping (pp. 215–243). Springer US.

- Mack KY. Childhood family disruptions and adult well-being: The differential effects of divorce and parental death. Death Studies. 2001;25(5):419–443. doi: 10.1080/074811801750257527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash HBH, Fullerton CS, Shear MK, Ursano RJ. Complicated Grief & Depression in young adults: Personality & Relationship Quality. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2014;202(7):539. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem NM, Day N, Shear MK, Day R, Reynolds CF, Brent D. Predictors of complicated grief among adolescents exposed to a peer's suicide. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2004;9(1):21–34. doi: 10.1080/1532502490255287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem NM, Moritz G, Walker M, Shear MK, Brent D. Phenomenology and correlates of complicated grief in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(4):493–499. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31803062a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem, N. M., Walker, M., Moritz, G., & Brent, D. A. (2008). Antecedents and sequelae of sudden parental death in offspring and surviving caregivers. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 162(5), 403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ogle CM, Rubin DC, Siegler IC. The impact of the developmental timing of trauma exposure on PTSD symptoms and psychosocial functioning among older adults. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(11):2191. doi: 10.1037/a0031985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oransky M, Hahn H, Stover CS. Caregiver and youth agreement regarding youths’ trauma histories: Implications for youths’ functioning after exposure to trauma. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42(10):1528–1542. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9947-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrantonio, F., De Gennaro, L., Di Paolo, M. C., & Solano, L. (2003). The Impact of Event Scale: validation of an Italian version. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55(4), 389–393. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, et al. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(8):e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamäki RL, El Sarraj E. Mother-child expression of psychological distress in war trauma. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;10(2):135–156. doi: 10.1177/1359104505051208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM, Hauf AMC, Wasserman MS, Silverman AB. Major depression in the transition to adulthood: Risks and impairments. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108(3):500. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Raveis, V. H., Siegel, K., & Karus, D. (1999). Children's psychological distress following the death of a parent. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(2), 165–180.

- Sandler I, Ayers TS, Tein JY, Wolchik S, Millsap R, Khoo ST, et al. Six-year follow-up of a preventive intervention for parentally bereaved youths: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164(10):907–914. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiege SJ, Khoo ST, Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA. Symptoms of internalizing and externalizing problems: Modeling recovery curves after the death of a parent. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31(6):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, P. R., & Worden, J. W. (1992). Children's reactions in the early months after the death of a parent. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 62(1), 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stikkelbroek Y, Bodden DH, Reitz E, Vollebergh WA, van Baar AL. Mental health of adolescents before and after the death of a parent or sibling. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2016;25(1):49–59. doi: 10.1007/s00787-015-0695-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, K. M., Lasker, J. N., Lohmann, J., & Toedter, L. J. (1992). Parents' grief following pregnancy loss: A comparison of mothers and fathers. Family Relations, 218–223.

- Stroebe W, Zech E, Stroebe MS, Abakoumkin G. Does social support help in bereavement? Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2005;24(7):1030–1050. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2005.24.7.1030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. The Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Donnellan MB, Moffitt TE, Robins RW, Poulton R, Caspi A. Low self-esteem during adolescence predicts poor health, criminal behavior, and limited economic prospects during adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(2):381. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano, R. J. (2014). Complicated grief and depression in young adults. J Nerv Ment Dis, 202, 00Y00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale-revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, R. A., & Weller, E. B. (1991). Depression in recently bereaved prepubertal children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(11), 1536. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wolchik SA, Tein JY, Sandler IN, Ayers TS. Stressors, quality of the child–caregiver relationship, and children's mental health problems after parental death: The mediating role of self-system beliefs. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(2):212–229. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worden JW, Silverman PR. Parental death and the adjustment of school-age children. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 1996;33(2):91–102. doi: 10.2190/P77L-F6F6-5W06-NHBX. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann JH, Park CL. Religion and spirituality in adjustment following bereavement: An integrative review. Death Studies. 2008;32(8):703–736. doi: 10.1080/07481180802289507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]