Abstract

This study examined patterns of caregiver factors associated with Trauma- Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) utilization among trauma-exposed youth. This study included 41 caregivers (caregiver age M = 36.1, SD = 9.88; 93% African American) of youth referred for TF-CBT, following a substantiated forensic assessment of youth trauma exposure. Prior to enrolling in TF-CBT, caregivers reported on measures for parenting stress, attitudes towards treatment, functional impairment, caregiver mental health diagnosis, and caregiver trauma experiences. Classification and regression tree methodology were used to address study aims. Predictors of enrollment and completion included: attitudes towards treatment, caregiver trauma experiences, and parenting stress. Several caregiver factors predicting youth service utilization were identified. Findings suggest screening for caregivers’ attitudes towards therapy, parenting stress, and trauma history is warranted to guide providers in offering caregiver-youth dyads appropriate resources at intake that can lead to increased engagement in treatment services.

Keywords: Enrollment, Engagement, Barriers, Family, Children

Introduction

Roughly 686,000 American youth are victims of abuse yearly (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and on Children 2013), and approximately 14% of American youth are exposed to a traumatic event during childhood (Becker-Blease et al. 2010). Youth who are exposed to abuse or trauma are at risk for developing mental health symptoms (Banyard et al. 2001; De Bellis et al. 2002; Lai et al. 2015; Widom et al. 2013) and problems in school (McGill et al. 2014). Trauma- Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) is a well-established, evidence-based treatment that is recommended as a first-line treatment for traumatized youth (Cohen et al. 2010; Cohen and Mannarino 2008a, b; Deblinger et al. 2011; Dittmann and Jensen 2014; Dorsey et al. 2011). In effectiveness studies, TF-CBT has demonstrated reductions in posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptoms and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in community settings (Cohen et al. 2011a; Webb et al. 2014). However, the majority of youth who are victims of abuse and trauma that need mental health services will not utilize TF-CBT. The focus of the current study was to identify and describe patterns of caregiver factors related to enrollment and completion of community-based TF-CBT among a sample of caregiver-youth dyads in which the youth had primarily experienced a traumatic event related to child sexual abuse.

TF-CBT is underutilized among youth who need services. Generally, only about 36% of youth needing mental health services receive treatment (Merikangas et al. 2011). Even when families begin treatment, roughly half will not complete treatment (see Nock and Ferriter 2005, for a review). More specific to TF-CBT, Jaycox et al. (2010) offered TF-CBT treatment free of charge to youth and families exposed to a traumatic event, Hurricane Katrina. Of the 60 children offered TF-CBT, only 22 (37%) attended the initial assessment, and only 14 (23%) children began TF-CBT. By the 10-month follow-up of the study, only nine children (15%) completed treatment.

It is particularly important to understand factors that promote service utilization among youth exposed to trauma. Youth reporting elevated mental health symptoms after traumatic events are likely to report chronic mental health symptoms (La Greca et al. 2013; Self-Brown et al. 2013). Further, enrollment and attendance are basic criteria necessary to the success of therapy. An understanding of patterns of factors predicting enrollment and completion in community settings may advance implementation of successful TF-CBT treatment by providing insight to aid clinical decision-making and to structure initial meetings with clients. This study focused on patterns of caregiver factors, as caregivers are the primary people who manage treatment participation for youth (Burnett-Zeigler and Lyons 2010; McKay and Bannon 2004; Nock and Ferriter 2005). In addition, caregivers are particularly important for TF-CBT, as caregivers promote optimal treatment outcomes through reinforcing skills from therapy and psychoeducation (Dorsey et al. 2014).

Traditionally, research has focused on examining contributions of single factors to service utilization (e.g., Alvidrez et al. 2010; Anyon et al. 2014; Pellerin et al. 2010). However, considering single factors by themselves may be misleading. Single factors rarely explain large proportions of variance in outcomes, and factors rarely occur in isolation from one another (Sameroff et al. 1993). Thus, it remains unclear how multiple factors may interact and manifest as patterns of barriers and promoters.

Identifying patterns of caregiver factors predicting TF-CBT service utilization is a difficult research question for several reasons. Theory in this area is unclear. Thus, forming a priori hypotheses about interaction patterns among factors is challenging. For example, numerous factors across different studies have been associated with service utilization, making it a complex task to discern patterns from these data. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of parental attitudes towards mental health services service engagement, where dissatisfaction and lack of trust in the system (Baker-Ericzén et al. 2013; Contractor et al. 2012), and negative help-seeking (Logan and King 2001; McKay et al. 2001) are shown to be consistent contributors to lower rates of service utilization among families. Further, perceptions of stigma around mental health services may decrease parental help-seeking and, therefore, service utilization (Dempster et al. 2013; Gronholm et al. 2015).

Conflicting findings are also abundant among other predictors. For example, some studies on family stress indicate that family stress (Briggs-Gowan et al. 2000; Dumas et al. 2007) and strain (Brannan et al. 2003; Chavira et al. 2009) promote intention to enroll. Others, however, describe family stress as a barrier to enrollment (Baker-Ericzén et al. 2010; Gopalan et al. 2011; Hall and Sandberg 2012), where families experiencing higher levels of stress may have insufficient resources or motivation to seek help, leading to avoidance of services (Harrison et al. 2004). Inconsistent results are also seen among studies on parent mental health symptomology and service utilization, in which positive associations have been found between self-reported parental psychopathology with service use (Burns et al. 2004; Olfson et al. 2003), while others have shown parental psychopathology as a barrier to adequate services among youth (Cornelius et al. 2001; Flisher et al. 1997). It is possible that conflicting findings have been found because stress and parental psychopathology may interact with other family variables when considering service utilization.

Another major factor hampering progress in identifying patterns of factors is the generally small sample size and low power of effectiveness studies. For example, in the aforementioned study by Jaycox et al. (2010), 60 children were assigned to TF-CBT treatment. Small sample sizes lead to small cell counts and limit researchers’ ability to test for interactions (Strobl et al. 2009). Given that effectiveness studies are underpowered to test interactions, little is known about moderators of service utilization and therefore patterns of factors that influence service utilization. It is important to consider moderators of service utilization, as multiple factors likely interact to influence attendance in child therapy (Nock and Ferriter 2005).

In this study, we demonstrate the utility of Classification and Regression Tree (CART) analysis in addressing the aforementioned barriers to identifying patterns in caregiver factors that may influence service utilization. CART, a data driven method, is a nonparametric methodology that creates a decision tree (Chang et al. 2012). CART methodology is gaining popularity in psychological research (Brabant et al. 2013; Doyle and Donovan 2014) and medical research (Kurosaki et al. 2011a, b) as a method to identify factors relating to prognostic outcomes. CART allows for discovering patterns in data that may be important for decision-making (Huang et al. 2007).

CART methodology has several important advantages that are relevant to the current study. First, CART is especially useful in cases where theory is unclear, as no hypotheses are identified a priori. In addition, CART is able to identify unforeseen patterns in data (Kurosaki et al. 2011a; Merkle and Shaffer 2011). Further, CART is a nonparametric method with no significance tests. Thus, power is not relevant, and CART is able to reveal interactions in small datasets such as those typically seen in effectiveness studies for TF-CBT (Merkle and Shaffer 2011; Strobl et al. 2009). Finally, CART may provide a nuanced understanding of how outcomes may change at different levels of predictors (Gruenewald et al. 2008). This is in contrast to traditional regression models, which focus on identifying average conditions associated with outcomes. CART’s ability to elucidate patterns that predict outcomes of therapy and reveal unforeseen interactions can be used to develop hypotheses and guide future research and decision-making.

In this study, we utilized CART methodology to examine patterns in the following factors that have been identified as relating to service utilization: parenting stress, caregiver attitudes towards treatment, caregiver functional impairment, caregiver mental health diagnosis, and caregiver trauma experiences. Specifically, we examined 1) caregiver factors predicting TF-CBT enrollment, and 2) caregiver factors predicting TF-CBT completion.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study included 41 caregiver-youth dyads, with youth referrals for treatment services following a forensic interview assessment substantiating youth trauma exposure or victimization. Youth were referred to a local child advocacy center from local law enforcement and child protection agencies for videotaped forensic interviews following an allegation of child victimization. Services were provided in an urban inner-city setting of a large southern city.

Caregivers ranged in age from 20 to 66 years (M = 36.1, SD = 9.88). Caregivers were predominantly female (88%) and African American (93%). Approximately 42% of caregivers reported an education level of high school graduate or GED, with 32% reporting some college. The majority of caregivers reported a total household income of less than $35,000 annually (73%). Over half of participants reported being unemployed (51%). Among those who were employed at the time of the study, 45% reported working less than 40 h per week. Approximately half of caregivers (51%) were single parents. Twenty-two percent reported being married. Youth in this study ranged in age from 3 to 18 years (M = 11.37, SD = 4.10). Approximately 95% of these youth were substantiated victims of sexual abuse, with 5% witnessing severe domestic or community violence.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Georgia State University Institutional Review Board. Inclusion criteria to participate included being a caregiver, legal guardian, or foster caregiver of the youth referred for TF-CBT services. Caregivers were required to have legal custody of the youth and must have resided in the same household as the referred youth. Caregivers were excluded from this study if they were unable to understand the consent form, displayed significant cognitive impairment, or had limited English proficiency.

Caregivers of youth with referrals for TF-CBT services at the child advocacy center were invited to participate in this study. At the time of intake, family advocates asked caregivers to complete a form inquiring about interest in participating in research opportunities. Caregivers who expressed willingness to participate were contacted by the members of the research team. Consenting caregivers completed two-part interviews. Caregivers completed a computer-administered survey using QDS™ (Questionnaire Development Software). As part of the larger study, caregivers also completed a semi-structured interview with a research assistant. Caregivers were compensated $55 for participating in the study.

A total of 86 caregivers expressed interest in the study and were subsequently contacted to participate. Of these caregivers, 16% were unable to be reached. Of those who expressed interest in scheduling an assessment, 13% did not show for a scheduled assessment, 11% were unable to be contacted to schedule an assessment, and 8% later refused to participate. In addition, 2% of caregivers sought services elsewhere and were deemed ineligible to participate. Thus, of the initial 86 caregivers, 48% (n = 41) provided full consent and completed the research interview.

Measures

The following measures, with the exception of service utilization, were caregiver-report measures collected from caregivers using QDS™ software as part of a larger study. Service utilization was assessed through chart review.

Parenting Stress

The Parenting Stress Index - Short Form (PSI-SF) (Abidin 1990) is a 36-item measure used to assess parenting stress among parents with children between 3 months and 10 years of age. The PSI-SF consists of three subscales, each consisting of 12 items (parental distress, parent-child dysfunctional interaction, difficult child characteristics). Caregivers were asked to score each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). A summary score was used to determine total stress among caregivers. Summary scores among caregivers ranged from 40 to 155, in which higher summary scores indicate higher levels of perceived stress among caregivers. Consistent with Abidin (1995), scores at or above 90 were considered clinically significant. The PSI demonstrated good internal consistency for this sample (α =0.95).

Attitudes Towards Treatment

The Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Psychological Health Scale - Short Form (ATSPPH) (Fischer and Farina 1995) was utilized to assess attitudes towards treatment. The ATSPPH is a 10-item measure assessing attitudes towards seeking professional treatment services. Caregivers were asked to rate items on a Likert scale from 0 (“disagree”) to 3 (“agree”). Scores were summed to yield a summary score potentially ranging from 0 to 30, with scores of 14 and higher indicating favorable attitudes towards treatment (Boisjolie 2013). The ATSPPH demonstrated adequate internal consistency for this sample (α = 0.59).

Functional Impairment

The Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS) (Foa et al. 1997) is a four-part, 49-item self-report measure, assessing trauma history among adults and frequency of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptomology due to trauma exposure during the past month. Part IV of the PDS was used to assess levels of daily life impairment among caregivers as related to their trauma exposure. Nine items were summed to obtain a summary score (potentially ranging from 0 to 9). Past research examining functional impairment has utilized the following cut-off ranges: no impairment = 0; mild = 1–2; moderate = 3–6; severe = 7–9 (Howgego et al. 2005). These items demonstrated good internal consistency for this sample (α = 0.93).

Caregiver Mental Health Diagnosis- PTS

Parts III and IV of the PDS (Foa et al. 1997) were used to assess frequency of PTS symptomology among caregivers. For each item in parts III and IV, caregivers responded from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“five or more times a week”). Scores for Parts III and IV were summed to produce a summary score of PTS symptomology, with potential scores ranging from 0 to 51. Clinical PTS symptom severity ranges were defined (i.e., mild = 1–10; moderate = 11–20; moderate-severe = 21–35; severe = 36 and greater) (McCarthy 2008). Internal consistency for this sample was good (α = .96). The PDS may also assess PTSD diagnosis based on criteria established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association 2000). A dichotomous variable was used to assess PTSD diagnosis among caregivers (PTSD diagnosis = 1, no PTSD diagnosis = 0).

Trauma Experiences

Part I of the PDS consists of 12 dichotomous items that screen for traumatic experiences among participants (e.g., sexual assault by a family member or stranger). Scores from dichotomous items were summed to produce a summary score (ranging from 0 to 12), in which higher scores indicate greater frequency of trauma exposure.

Enrollment and Completion

Clinical coordinators of the child advocacy center reviewed charts for youth whose caregivers completed the questionnaire and interview measures. Charts were reviewed on a monthly basis for youth service utilization, which included youth enrollment in therapy, the number of sessions youth attended, and youth service completion. For this study, caregiver-child dyad enrollment in TF-CBT was defined as dyads who attended at least one TF-CBT session at the local child advocacy center. Completion was defined as dyads who completed the documented chart treatment plan for TF-CBT and who graduated from therapy services.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics Software version 20 (IBM Corporation 2011). Means, frequencies, and clinical significance were examined among applicable study items for caregivers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Information for Study Variables

| Variables (possible score range) | Caregivers (n = 41) M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 36.10 (9.88) |

| Parenting Stress (0–180) | 74.07 (24.74) |

| Attitudes Towards Treatment (0–30) | 24.44 (4.19) |

| Functional Impairment (0–9) | 3.85 (3.56) |

| PTS Symptomology (0–51) | 9.33 (12.46) |

| Trauma Experiences (0–12) | 1.78 (2.03) |

PTS Posttraumatic Stress

Caregiver Descriptive Statistics

The mean total parenting stress score among caregivers was 74.07 (SD = 24.74). Approximately 22% of caregivers met clinically significant levels of stress (i.e., raw score > 90) (Abidin 1995). With regards to attitudes towards treatment, the mean total score was 24.44 (SD = 4.19), indicating that on average, caregivers reported favorable attitudes towards treatment in this sample (i.e., scores ≥14) (Boisjolie 2013).

On average, caregiver functional impairment scores fell in the ‘moderate’ level of impairment (Howgego et al. 2005), with a mean score of 3.85 (SD = 3.56). The mean level of PTS symptoms was 9.33 (SD = 12.46), indicating mild levels of PTS severity among caregivers. With respect to mental health diagnosis, 20% of caregivers met criteria for PTSD. Approximately 56% of caregivers reported at least one traumatic life experience in their past (M = 1.78, SD = 2.03). The most frequently reported traumatic events were sexual (37%) and non-sexual assault (32%) by a family member or someone that caregivers knew.

Service Utilization

Of the 41 caregiver-youth dyads, 29 (71%) enrolled in TF-CBT, and 9 (22%) completed services.

Caregiver Factors Predicting Service Utilization

For caregiver factor analyses, the data mining software IBM SPSS Modeler version 16.0 (IBM Corporation 2014) was utilized for CART analyses. As noted earlier, CART is a nonparametric regression method. In building our decision trees, we examined two outcomes, enrollment and completion. The following caregiver factors were examined as potential predictors of enrollment and completion: parenting stress, attitudes towards treatment, functional impairment, mental health diagnosis, and trauma experiences.

Decision trees were formed by determining which predictor variable of interest, and at what cutoff point, optimally divided the full sample into two prognostic subgroups as homogenous as possible within subgroup for the dependent variable being examined (i.e., for enrollment or completion). This two-choice branching method was repeated for all newly defined subgroups. Branching was stopped when the sample size for a subgroup was below 5% of the sample.

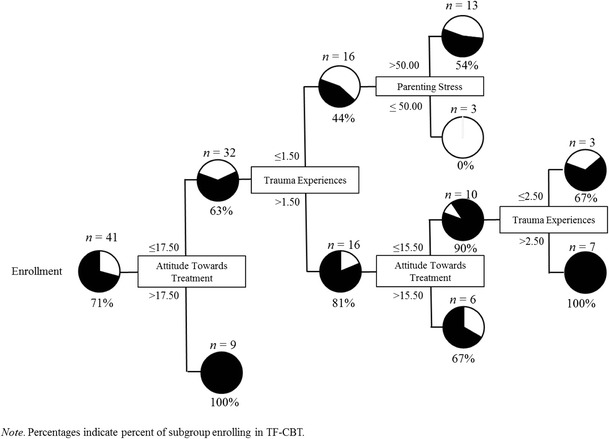

Caregiver Factors Predicting Enrollment

CART analysis on the 41 caregiver-youth dyads in this study yielded the decision tree depicted in Fig. 1. From the five caregiver factors examined (parenting stress, attitudes towards treatment, functional impairment, mental health diagnosis, and trauma experiences), attitudes towards treatment, trauma experiences, and parenting stress were predictive of enrollment.

Fig. 1.

Caregiver Factors Predicting Enrollment

In the CART, attitudes towards treatment was the initial split, with an optimal cutoff of 17.5 on the scale. Among families whose caregiver had more positive attitudes towards treatment (i.e., > 17.5 on the ATSPPH), 100% enrolled in TF-CBT. In contrast, among those whose caregiver reported less favorable attitudes towards treatment (i.e., ≤ 17.5 on the ATSPPH), probability of enrollment in TF-CBT was 63%. This subgroup was further characterized by a second split for caregiver trauma experiences, with an optimal cutoff of 1.5 events. Among caregivers who reported experiencing more traumatic events, this group was further split by attitudes towards treatment and trauma experiences. Among parents with moderately favorable attitudes towards treatment (i.e., scores between 15.5 and 17.5 on the ATSPPH), 67% enrolled in treatment. Among those with less favorable attitudes towards treatment (i.e., scores ≤15.5 on the ATSPPH), those with more trauma experiences (> 2.5) were likely to enroll in treatment (i.e., 100% enrolled), while among those with two trauma experiences (i.e., between 1.5 and 2.5), 67% enrolled. In contrast, among families whose caregivers reported fewer traumatic events (i.e., ≤ 1.5), 54% of caregivers who reported higher levels of parenting stress enrolled in treatment. Among those with lower levels of parenting stress, none enrolled in treatment.

Caregiver Factors Predicting Completion

CART analysis for completion yielded the decision tree depicted in Fig. 2. From the five caregiver factors examined, caregiver attitudes towards treatment, trauma experiences, and parenting stress were predictive of completion.

Fig. 2.

Caregiver Factors Predicting Completion

In the CART analysis, attitudes towards treatment was selected as the initial split, with an optimal cutoff score of 0. Among those families whose caregivers had positive attitudes towards treatment (i.e., scores >0 on the ATSPPH), 50% completed TF-CBT. In contrast, among families whose caregivers reported no favorable attitudes towards treatment, 15% completed treatment. This subgroup was further characterized by a split for parenting stress, with an optimal cut off score of 98. Among those who reported higher levels of parenting stress (i.e., scores >98.0 on the PSI/SF), 50% completed TF-CBT. Treatment completion among families who reported lower levels of parenting stress (i.e., scores ≤98.0 on the PSI/SF) was 10%. This group was further characterized by a second split for attitudes towards treatment, with an optimal cutoff score of 20 on the scale. Caregivers reporting more favorable attitudes (i.e., scores >20 on the ATSPPH), were more likely to complete TF-CBT (33.33%), in contrast to caregivers with less favorable attitudes towards treatment (8%). The latter subgroup was further split by number of trauma experiences. Among caregivers reporting more trauma experiences (i.e., >4), 33.33% completed TF-CBT. Among those with fewer reported trauma experiences, 9% of caregivers with higher levels of parenting stress (i.e., >66.50 on the PSI/SF) completed treatment. In contrast, no caregivers who reported lower levels of parenting stress completed treatment services.

Discussion

We examined factors influencing enrollment and completion of TF-CBT delivered in a community setting with a sample of caregivers whose child had a substantiated case of child sexual abuse or severe family/community violence exposure. Caregiver attitudes towards therapy, caregiver trauma experiences, and parenting stress were important predictors of service utilization. Caregiver attitudes towards treatment emerged as the strongest predictor of enrollment and completion. However, multiple interactions between factors were identified in CART analyses. These findings are discussed in detail below.

Caregiver Factors Predicting Enrollment

Overall, the strongest predictor of enrollment was caregiver attitudes towards treatment. Attitudes may include openness to seeking treatment for emotional problems, and value and need in seeking treatment (Elhai et al. 2008). Families with caregivers who had positive attitudes towards treatment were likely to enroll in treatment. Our finding is in keeping with research demonstrating positive associations between caregiver attitudes towards treatment and initial engagement in therapy (McKay et al. 2001). Based on our findings, families with positive attitudes towards treatment are unlikely to need additional engagement strategies related to decisions to enroll in therapy.

Our findings suggest that it is particularly important to consider innovative approaches to engage those caregivers with more negative attitudes towards treatment. Linking to the larger literature on caregiver attitudes towards treatment, our findings are in keeping with research that suggests that parents who are resistant to treatment are less likely to engage (Baker-Ericzén et al. 2010). These findings are also in line with emerging research on engaging families in TF-CBT. For example, Dorsey et al. (2014) conducted a brief engagement intervention for children and foster parents involved in TF-CBT. The engagement intervention specifically targeted discussions of negative experiences with therapy. Compared to families who did not receive an engagement intervention, families who did receive an engagement intervention were significantly more likely to attend four or more TF-CBT sessions. Notably, caretaker attitudes have rarely been examined in prior research focusing on caregiver characteristics that can serve as barriers to treatment. In fact, the majority of research in this area has focused specifically on caregiver demographic characteristics that are not as amenable to potential intervention. Thus, the assessment of caregiver characteristics that may be addressed in engagement interventions is a significant strength of the current study.

Importantly, caregivers in this sample with more negative attitudes towards therapy were more likely to enroll in therapy if they had experienced their own traumatic experience. Therefore, there was an interaction between attitudes towards treatment and traumatic experiences. This finding is somewhat counterintuitive, as caregiver trauma is linked to higher levels of caregiver PTSD symptomatology (Self-Brown et al. 2014). One would expect caregiver trauma to have a potential negative impact on therapy participation, given that avoidance is a hallmark symptom of PTSD. However, caregivers’ own experiences with trauma may heighten awareness and recognition of mental health needs among their children. In turn, caregiver problem recognition may promote help-seeking attitudes and subsequent treatment utilization (Godoy et al. 2014; Teagle 2002). This interesting finding on trauma history highlights the importance of screening for caregiver trauma history. Having this information may allow therapists to acknowledge and empathize with caretakers’ experiences (Cohen et al. 2011b). Again, the impact of caregiver trauma has been under-researched as a potential barrier to treatment.

Further, parenting stress interacted with attitudes towards therapy and trauma experiences to predict enrollment. Among those with more negative attitudes towards treatment, caregivers who reported low levels of trauma experiences and high levels of parenting stress were highly unlikely to enroll their children in TF-CBT. Clearly, understanding more about caretakers’ attitudes toward therapy, trauma history, and parenting stress can be helpful in predicting therapy service utilization. Therapists should consider the implementation of strategies to improve engagement with caretakers who have a combination of negative attitudes towards therapy, low levels of trauma exposure, and high parenting stress, as these data suggest these caretakers were the least likely to enroll their traumatized child in TF-CBT.

Caregiver Factors Predicting Completion

Caregiver experiences with trauma and parenting stress interacted to predict completion of TF-CBT. Families with caregivers who reported few traumatic experiences were highly unlikely to complete treatment. Interestingly, families whose caregivers reported the highest levels of parenting stress were more likely to complete TF-CBT. At the same time, families reporting lower levels of parenting stress were more likely to complete treatment if the caregiver reported experiencing multiple traumatic events or had more favorable attitudes towards treatment.

Our finding on the role of parenting stress in enrollment and completion of TF-CBT may help explain some of the conflicting findings in the literature, where family stress has been shown to be both a barrier (Gopalan et al. 2011; Hall and Sandberg 2012; Koverola et al. 2007) and a promoter of enrollment and engagement (Dumas et al. 2007). For example, research by McKay et al. (2001) among 100 caregivers of youth with mental health treatment referrals indicated that higher levels of family stress predicted lower levels of attendance and engagement in services. Further, a study by Pellerin et al. (2010) examined psychotherapy retention and attrition among 250 caregiver-youth dyads and found non-completers of services were more likely to endorse higher levels of parental stress than those who completed services. In contrast, in a study of service utilization among 451 mothers of preschoolers, Dumas et al. (2007) found that mothers were more likely to intend to enroll in services if they reported high levels of stressors.

Based on our study, the role of parenting stress depends on both attitudes towards treatment and caregiver trauma experiences. These findings suggest that engagement strategies need to consider both attitudes towards treatment and varying levels of past traumatic experiences and parenting stress among caregivers. As an example from the literature, Kazdin and Whitley (2003) evaluated effects of an augmented, evidence-based treatment for child mental health disorders that included an additional training component targeting parental stress. Intervention participation led to a decrease in reported stress and barriers among parents, and positive intervention outcomes among children. However, further research is still needed to explore whether similar modifications in trauma settings may be effective in improving parent outcomes affecting treatment enrollment and engagement.

Limitations

Limitations should be considered when evaluating this study. Our sample was predominantly female and African American. Although this is a strength of the study, reflecting families served in our community, findings may not translate to other samples. Further, this study focused on caregiver factors. Future studies that include child factors that influence TF-CBT utilization are warranted.

Research Implications

Future research should consider CART methods as a useful tool for advancing how mental illness is treated. The social sciences are often negatively biased towards exploratory methods (King and Resick 2014). However, our findings illustrate the utility of CART methodology. In this study, CART analyses identified interactions between multiple factors. Identifying these interactions would likely not have been possible if a more traditional regression method had been used, given the small sample size of the study (Merkle and Shaffer 2011; Strobl et al. 2009). Thus, findings have the potential to reveal information about moderators of service utilization. This is critical, given that TF-CBT is an effective, but underutilized treatment.

Clinical and Policy Implications

Initial screeners for TF-CBT treatment may consider including assessments of caregiver attitudes towards treatment, trauma experiences, and parenting stress. Caretakers in this study who reported more negative attitudes towards treatment were less likely to enroll their child in TF-CBT or complete treatment. Importantly, clinical research has identified engagement strategies, such as motivational interviewing and McKay’s Training Intervention for the Engagement of Families (http://www.tiesengagement.com/), which can boost caretaker involvement in therapy services (Dorsey et al. 2014). Providers may also consider adjunctive therapy for caregivers reporting higher levels of trauma experiences or parenting stress.

To date, a critical gap in the literature is the lack of knowledge about moderating factors that influence utilization of TF-CBT. This gap limits our progress in refining program delivery and limits the benefit of increased access to highly effective evidence-based practices. Future research should consider including data driven methods aimed to further delineate factors associated with service utilization. This would address an additional gap in the research literature, the need for replicated findings related to caregiver factors influencing service utilization. The CART analyses used in this study may not translate to other samples, given that CART is a data driven methodology. It will be important to validate these findings with additional independent samples (Schwartz et al. 2011). Addressing these issues in future research presents an opportunity to advance clinical delivery in child mental health.

Perhaps what is most interesting about the application of CART methods in the current study was the identification of factors that have been traditionally considered barriers (e.g., caretaker trauma and stress) to treatment (Baker-Ericzén et al. 2010; Gopalan et al. 2011; Hall and Sandberg 2012; Mowbray et al. 2004) as factors that, under certain conditions, enhanced likelihood to enroll in and complete therapy. Although counterintuitive, this information may help identify families at greatest risk for poor service utilization. Further, this information provides avenues for ways to utilize positive strategies to engage caregivers. Only research that allows us to empirically derive these cut-offs and drivers of service utilization can advance the access of evidence-based practices to youth in greatest need.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Georgia Center for Child Advocacy, Emory Center for Injury Prevention (PI: Shannon Self-Brown, Ph.D.). The authors would like to thank Brooke Beaulieu, Constance Ogokeh, and Ryan Savage for their feedback on this manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts to report.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

All Procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

References

- Abidin, R. R. (1990). Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Pediatric Psychology Press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Abidin RR. Parenting stress index 3rd edition: Professional manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, Patel SG. The relationship between stigma and other treatment concerns and subsequent treatment engagement among black mental health clients. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2010;31(4):257–264. doi: 10.3109/01612840903342266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, D.C.: DSM-IV-TR; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anyon Y, Ong SL, Whitaker K. School-based mental health prevention for Asian American adolescents: risk behaviors, protective factors, and service use. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2014;5(2):134. doi: 10.1037/a0035300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzén MJ, Jenkins MM, Brookman-Frazee L. Clinician and parent perspectives on parent and family contextual factors that impact community mental health Services for Children with behavior problems. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2010;39(6):397–419. doi: 10.1007/s10566-010-9111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzén MJ, Jenkins MM, Haine-Schlagel R. Therapist, parent, and youth perspectives of treatment barriers to family-focused community outpatient mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22(6):854–868. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9644-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard V, Banyard L, Williams J, Siegel The long-term mental health consequences of child sexual abuse: an exploratory study of the impact of multiple traumas in a sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14(4):697–715. doi: 10.1023/A:1013085904337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Blease KA, Turner HA, Finkelhor D. Disasters, victimization, and children’s mental health. Child Development. 2010;81(4):1040–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisjolie, J. (2013). Gender role conflict and attitudes toward seeking help. University of St. Thomas.

- Brabant M-E, Hébert M, Chagnon F. Identification of sexually abused female adolescents at risk for suicidal ideations: a classification and regression tree analysis. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2013;22(2):153–172. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2013.741666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannan AM, Heflinger CA, Foster EM. The role of caregiver strain and other family variables in determining Children’s use of mental health services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003;11(2):77–91. doi: 10.1177/106342660301100202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Horwitz SM, Schwab-Stone ME, Leventhal JM, Leaf PJ. Mental health in pediatric settings: distribution of disorders and factors related to service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(7):841–849. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200007000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett-Zeigler I, Lyons JS. Caregiver factors predicting service utilization among youth participating in a school-based mental health intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(5):572–578. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9331-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, Barth RP, Kolko DJ, Campbell Y, Landsverk J. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: a national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y-J, Chen L-J, Chang Y-J, Chung K-P, Lai M-S. Risk groups defined by recursive partitioning analysis of patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma treated with colorectal resection. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2012;12(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavira DA, Garland A, Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL. Child anxiety disorders in public systems of care: comorbidity and service utilization. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2009;36(4):492–504. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9139-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Mannarino A. Disseminating and implementing trauma-focused CBT in community settings. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2008;9(4):214–226. doi: 10.1177/1524838008324336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Mannarino A. Trauma-focused cognitive Behavioural therapy for children and parents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2008;13(4):158–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Berliner L, Mannarino A. Trauma focused CBT for children with co-occurring trauma and behavior problems. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(4):215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Mannarino AP, Iyengar S. Community treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder for children exposed to intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(1):16–21. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Mannarino A, Murray LK. Trauma-focused CBT for youth who experience ongoing traumas. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35(8):637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor LFM, Celedonia KL, Cruz M, Douaihy A, Kogan JN, Marin R, Stein BD. Mental health services for children of substance abusing parents: voices from the community. Community Mental Health Journal. 2012;48(1):22–28. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9357-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Pringle J, Jernigan J, Kirisci L, Clark DB. Correlates of mental health service utilization and unmet need among a sample of male adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Keshavan MS, Frustaci K, Shifflett H, Iyengar S, Beers SR, Hall J. Superior temporal gyrus volumes in maltreated children and adolescents with PTSD. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51(7):544–552. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen J, Runyon MK, Steer RA. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(1):67–75. doi: 10.1002/da.20744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster R, Wildman B, Keating A. The role of stigma in parental help-seeking for child behavior problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(1):56–67. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.700504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmann I, Jensen TK. Giving a voice to traumatized youth—Experiences with trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38(7):1221–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Briggs EC, Woods BA. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2011;20(2):255–269. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Pullmann MD, Berliner L, Koschmann E, McKay M, Deblinger E. Engaging foster parents in treatment: a randomized trial of supplementing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with evidence-based engagement strategies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38(9):1508–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle SR, Donovan DM. Applying an ensemble classification tree approach to the prediction of completion of a 12-step facilitation intervention with stimulant abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(4):1127. doi: 10.1037/a0037235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Nissley-Tsiopinis J, Moreland AD. From intent to enrollment, attendance, and participation in preventive parenting groups. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16(1):1–26. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9042-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Schweinle W, Anderson SM. Reliability and validity of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form. Psychiatry Research. 2008;159(3):320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E. H., & Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help: A Shortened Form and Considerations for Research. Journal of College Student Development, 36(4), 368–73.

- Flisher AJ, Kramer R, Grosser R, Alegria M, Bird H, Bourdon K, et al. Correlates of unmet need for mental health services by children and adolescents. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27(05):1145–1154. doi: 10.1017/S0033291797005412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K. The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9(4):445. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.9.4.445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy L, Mian ND, Eisenhower AS, Carter AS. Pathways to service receipt: modeling parent help-seeking for childhood mental health problems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2014;41(4):469–479. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0484-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Bannon W, Dean-Assael K, Fuss A, Gardner L, LaBarbera B, McKay M. Multiple family groups: an engaging intervention for child welfare–involved families. Child Welfare. 2011;90(4):135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronholm PC, Ford T, Roberts RE, Thornicroft G, Laurens KR, Evans-Lacko S. Mental health service use by young people: the role of caregiver characteristics. PloS One. 2015;10(3):e0120004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald TL, Mroczek DK, Ryff CD, Singer BH. Diverse pathways to positive and negative affect in adulthood and later life: an integrative approach using recursive partitioning. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(2):330. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CA, Sandberg JG. “We shall overcome”: a qualitative exploratory study of the experiences of African Americans who overcame barriers to engage in family therapy. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2012;40(5):445–458. doi: 10.1080/01926187.2011.637486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison ME, McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr Inner-city child mental health service use: the real question is why youth and families do not use services. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40(2):119–131. doi: 10.1023/B:COMH.0000022732.80714.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howgego IM, Owen C, Meldrum L, Yellowlees P, Dark F, Parslow R. Posttraumatic stress disorder: an exploratory study examining rates of trauma and PTSD and its effect on client outcomes in community mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2005;5:21–21. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M-J, Chen M-Y, Lee S-C. Integrating data mining with case-based reasoning for chronic diseases prognosis and diagnosis. Expert Systems with Applications. 2007;32(3):856–867. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2006.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation . IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 20.0) Armonk: IBM Corp; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation . IBM SPSS Modeler (Version 16.0) Armonk: IBM Corp; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Cohen J, Mannarino AP, Walker DW, Langley AK, Gegenheimer KL, et al. Children’s mental health care following hurricane Katrina: a field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23(2):223–231. doi: 10.1002/jts.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(3):504. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, M. W., & Resick, P. A. (2014). Data mining in psychological treatment research: A primer on classification and regression trees. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(5), 895. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Koverola C, Murtaugh CA, Connors KM, Reeves G, Papas MA. Children exposed to intra-familial violence: predictors of attrition and retention in treatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2007;14(4):19–42. doi: 10.1300/J146v14n04_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki M, Sakamoto N, Iwasaki M, Sakamoto M, Suzuki Y, Hiramatsu N, et al. Sequences in the interferon sensitivity-determining region and core region of hepatitis C virus impact pretreatment prediction of response to PEG-interferon plus ribavirin: data mining analysis. Journal of Medical Virology. 2011;83(3):445–452. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki M, Sakamoto N, Iwasaki M, Sakamoto M, Suzuki Y, Hiramatsu N, et al. Pretreatment prediction of response to peginterferon plus ribavirin therapy in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C using data mining analysis. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;46(3):401–409. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Lai BS, Llabre MM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein MJ. Children’s postdisaster trajectories of PTS symptoms: predicting chronic distress. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2013;42(4):351–369. doi: 10.1007/s10566-013-9206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai BS, Kelley ML, Harrison KM, Thompson JE, Self-Brown S. Posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms among children after hurricane Katrina: a latent profile analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24(5):1262–1270. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9934-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan DE, King CA. Parental facilitation of adolescent mental health service utilization: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8(3):319–333. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy S. Post-traumatic stress diagnostic scale (PDS) Occupational Medicine. 2008;58(5):379. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqn062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill, T. M., Self-Brown, S. R., Lai, B. S., Cowart-Osborne, M., Tiwari, A., LeBlanc, M., & Kelley, M. L. (2014). Effects of exposure to community violence and family violence on school functioning problems among urban youth: the potential mediating role of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Frontiers in Public Health, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13(4):905–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Pennington J, Lynn CJ, McCadam K. Understanding urban child mental health service use: two studies of child, family, and environmental correlates. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2001;28(4):475–483. doi: 10.1007/BF02287777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J-p, Burstein ME, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle EC, Shaffer VA. Binary recursive partitioning: background, methods, and application to psychology. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2011;64(1):161–181. doi: 10.1348/000711010X503129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray CT, Lewandowski L, Bybee D, Oyserman D. Children of mothers diagnosed with serious mental illness: patterns and predictors of service use. Mental Health Services Research. 2004;6(3):167–183. doi: 10.1023/B:MHSR.0000036490.10086.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Ferriter C. Parent management of attendance and adherence in child and adolescent therapy: a conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-4753-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Pincus HA, Weissman MM. Parental depression, child mental health problems, and health care utilization. Medical Care. 2003;41(6):716–721. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000064642.41278.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin KA, Costa NM, Weems CF, Dalton RF. An examination of treatment completers and non-completers at a child and adolescent community mental health clinic. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46(3):273–281. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, Baldwin C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: the influence of social and family risk factors. Child Development. 1993;64(1):80–97. doi: 10.2307/1131438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Sprangers MA, Oort FJ, Ahmed S, Bode R, Li Y, Vollmer T. Response shift in patients with multiple sclerosis: an application of three statistical techniques. Quality of Life Research. 2011;20(10):1561–1572. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self-Brown S, Lai BS, Thompson JE, McGill T, Kelley ML. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories in hurricane Katrina affected youth. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;147(1–3):198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self-Brown S, Lai BS, Harbin S, Kelley ML. Maternal posttraumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories following hurricane Katrina: an initial examination of the impact of maternal trajectories on the well-being of disaster-exposed youth. International Journal of Public Health. 2014;59(6):957–965. doi: 10.1007/s00038-014-0596-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobl C, Malley J, Tutz G. An introduction to recursive partitioning: rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychological Methods. 2009;14(4):323. doi: 10.1037/a0016973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teagle SE. Parental problem recognition and child mental health service use. Mental Health Services Research. 2002;4(4):257–266. doi: 10.1023/A:1020981019342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration, & on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2013). Child maltreatment 2012. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- Webb C, Hayes AM, Grasso D, Laurenceau J-P, Deblinger E. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for youth: effectiveness in a community setting. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6(5):555. doi: 10.1037/a0037364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja S, Wilson HW, Allwood M, Chauhan P. Do the long-term consequences of neglect differ for children of different races and ethnic backgrounds? Child Maltreatment. 2013;18(1):42–55. doi: 10.1177/1077559512460728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]