Abstract

Impairments in Caregiving (ICG) secondary to mental illness and substance use have been linked to adverse outcomes in children. Little is known, however, about whether outcomes vary by type of ICG, exposure to co-occurring traumas, or mechanisms of maladaptive outcomes. Clinic-referred youth age 7–18 years (n = 3988) were compared on ICG history, demographics, trauma history, and mental health symptoms. Child trauma exposure was tested as a mediator of ICG and child symptoms. Youth with ICG were at heightened risk for trauma exposure, PTSD, internalizing symptoms, total behavioral problems, and attachment problems, particularly youth with multiple types of ICG. Effect sizes were moderate to large for PTSD, internalizing symptoms, and total behavioral problems. Number of trauma types mediated the relationship between ICG and child symptoms. ICG was related to trauma exposure within and outside the family context. Understanding these links has important implications for interrupting intergenerational trauma and psychopathology.

Keywords: Impaired caregiving, Children and adolescents, Parent, Mental health, Alcohol and substance abuse

Introduction

When caregivers are affected by their own impairments, such as alcohol/substance use and mental illness, their ability to meet their child’s physical and emotional needs is compromised, a term subsequently referred to as impaired caregiving (ICG). Alcohol and substance use among parents is common, with population rates ranging from 3 to 10 % (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2009). Prevalence rates of mental illness in parents have been more difficult to accurately quantify, although it is known that adults with mental illness are as likely to become parents as psychologically healthy adults (Nicholson et al. 2002).

Existing literature has established that caregiver mental illness and substance use are related to adverse childhood outcomes. Maternal depression, in particular, has been the focus of multiple investigations demonstrating significant associations with child internalizing and externalizing problems, physical complaints, and poor academic functioning (Goodman et al. 2011; Lewinsohn et al. 2005; Olfson et al. 2003). Similarly, caregiver alcohol and substance use has been associated with a range of child emotional and behavioral problems (Morgan et al. 2010; Osborne and Berger 2009). ICG also poses implications for child trauma exposure, with numerous studies demonstrating that caregivers with substance use or mental health problems are at increased risk for abusing or neglecting their children (e.g., Kohl et al. 2011); these associations remain even after accounting for demographic factors, such as socioeconomic status, sex, and age of the child (Chaffin et al. 1996).

The impact and scope of child trauma exposure is vast and far-reaching. Approximately two-thirds of youth in the United States are exposed to at least one traumatic event over the course of childhood (Copeland et al. 2007). Child trauma exposure has been associated with a myriad of psychiatric, physical health, and functional problems among youth, including mood and anxiety disorders (Bolger and Patterson 2001; Cohen et al. 2001; Heim and Nemeroff 2001), posttraumatic stress disorder (Gabbay et al. 2004; Kearney et al. 2010), alcohol and substance abuse (Thornberry et al. 2001), suicidality (Turner et al. 2006), learning problems and poor academic achievement (Veltman and Browne 2001), and poor physical health (Flaherty et al. 2006; Goodwin and Stein 2004; Hussey et al. 2006). Although early studies of child trauma predominantly focused on single exposures or a limited range of trauma types (e.g., sexual trauma, motor vehicle accidents), it is now known that the majority of trauma-exposed youth experience multiple types of trauma (Finkelhor et al. 2007), and the risk of multiple exposures accumulates over time (Breslau et al. 2014). Retrospective studies on the long-term impact of child trauma, such as the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) studies, have repeatedly demonstrated a dose response relationship between number of ACEs and adverse outcomes into adulthood, including psychiatric problems, physical health difficulties, and premature death (Anda et al. 2006; Edwards et al. 2005; Felitti et al. 1998). Similar findings have been demonstrated in prospective samples of youth (Appleyard et al. 2005; Sameroff et al. 2003). When compared to single incident trauma exposure, youth exposure to multiple traumas and stressors is strongly related to psychiatric and behavioral problems (Finkelhor et al. 2007; Turner et al. 2006), particularly for those exposed to interpersonal (e.g., abuse, assault) versus non-interpersonal trauma types (e.g., witnessing violence, natural disaster/accidents; Ford et al. 2010).

Despite these findings, existing literature on impaired caregiving and child trauma is somewhat limited by: (1) reporting on a narrow range of child trauma exposures among ICG-affected youth (e.g., abuse and neglect), without examining associations with other trauma types (e.g., assault, community violence), and (2) focusing solely on caregiver mental health (e.g., maternal depression) or alcohol/substance use, but not both. In addition, it is possible that the cumulative impact of trauma exposure during childhood serves as a key environmental mechanism between caregiver impairment and child psychopathology. Only one known study (Mustillo et al. 2011) has addressed this research question, using longitudinal data on 1813 children and parents from a nationally representative child-welfare sample, the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW). Results demonstrated that child neglect, but not abuse, mediated the effect between parent depression and child mental health problems. Again, this study was limited by focusing on a limited range of types of trauma exposure and one type of parent mental illness.

Taking a poly-trauma perspective in research investigations is critical because it is plausible that multiple types of trauma may share common etiologies. Shared risk factors may exist at a number of ecological levels (Bronfenbrenner 1992), including child, family, community, and societal contexts. However, some risk factors may be more challenging to influence, either because they are less amenable to change (e.g., being born with a developmental disability) or may require long-term societal changes and policy reform (e.g., reducing poverty). Arguably, one of the most promising prevention targets for a “high return on investment” is the promotion of caregiver capacity to support child development (Shonkoff et al. 2012). Given the potential for negative outcomes, it is imperative that we begin to identify whether exposure to multiple or co-occurring types of trauma convey shared risks. Equally as important is the ability to delineate potential pathways and mechanisms that can be utilized to minimize risk and support healthy development.

The present study aimed to address some of the limitations in the existing literature using a large dataset of clinic-referred, trauma-exposed youth from across the United States. Given high rates of exposure to trauma and severe stressors in this population, we aimed to more accurately reflect the experiences of these youth by extending the findings of previous studies (e.g., Mustillo et al. 2011) in two important ways: (1) comparing effects of multiple types of caregiver impairment, rather than focusing solely on parental depression, and (2) including a wider range of trauma exposures in the model, beyond abuse and neglect. Youth who were receiving assessment and treatment services at a National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) center, with and without histories of ICG, were compared on a broad range of traumatic experiences, consistent with a poly-victimization framework. To this end, we examined the following three hypotheses: (1) Youth with impaired caregiving histories would have exposure to more trauma types compared to children without impaired caregiving histories. Specifically, we compared the total number and types of trauma across a broad range of exposures for children with and without impaired caregiving histories. Descriptively, we postulated that this relationship would be strongest for intra-familial and interpersonal traumas (i.e., sexual trauma, maltreatment, violence), and for children with exposure to both caregiver mental illness and alcohol/substance abuse; (2) Youth with impaired caregiving histories would have significantly higher rates of emotional and behavioral symptoms after accounting for demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, race/ethnicity), total number of trauma types, and the site at which a child was assessed. Descriptively, we hypothesized that the relationship would be most pronounced for children with exposure to both caregiver mental illness and alcohol/substance abuse as compared to children without impaired caregiving histories; (3) Finally, we examined whether the total number of trauma types mediated the relationship between impaired caregiving and child symptoms.

Methods

Participants

The NCTSN Core Data Set (CDS) served as the data source for the present study. The NCTSN was created by Congress in 2000 as part of the Children’s Health Act to raise the standard of care and increase access to services for children and families exposed to traumatic events. This unique network of mental health clinics, residential treatment centers, juvenile justice programs, schools, and hospitals serves children and their families across the United States. The NCTSN is administered by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and coordinated by the UCLA-Duke University National Center for Child Traumatic Stress (NCCTS), which guides NCTSN collaborative efforts, including data collection.

Approximately, 14,088 youth, 0–21 years were referred to NCTSN centers for trauma-focused services between 2004 and 2010. Data were collected from 56 NCTSN centers and included information on demographic characteristics, child trauma history, emotional and behavioral functioning, treatment, and service utilization. Data were included in the present study if youth were age 7–18 years (n = 10,608), had at least one confirmed trauma exposure (n = 8422), and completed both the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; n = 4973). Given the focus on impaired caregiving, cases with missing information on exposure to an impaired primary caregiver (n = 589) and/or the type of caregiver impairment (n = 249) were excluded. Additionally, cases with an impaired caregiver due to medical illness only (n = 104) or other unspecified impairment (n = 292) were excluded, as this type of impairment is not theoretically linked to trauma exposure. This resulted in a final sample size of 3988 cases.

Measures

Demographic Variables

Demographic variables were completed at baseline and included: sex, age, race/ethnicity (White, non-Hispanic; African American, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; other, non-Hispanic), current legal guardian (e.g., parent, state, other relative, other), current primary residence (home with parents, with other relatives, foster care, other), and eligibility for public insurance, which served as a proxy for socioeconomic status.

Trauma History Profile

The Trauma History Profile (THP) portion of the CDS was derived from the trauma history screening component of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (PTSD-RI; Steinberg et al. 2013; Steinberg et al. 2004). Mental health clinicians and staff completed the THP using multiple sources of information (e.g., client charts, CPS reports, clinical interview, caregiver and child reports). The THP included assessment for exposure to 19 specific types of traumatic events, including impaired caregiving. The definition for endorsement of impaired caregiving required that, due to the type of impairment (e.g., mental illness), the primary caregiver was unable to: (1) provide the child with adequate nurturance, guidance, and support, and (2) attend to the child’s basic developmental needs. Types of caregiver impairment examined in this study included: mental illness, alcohol/substance abuse, or both. Impaired caregivers were the person(s) identified as the primary caregiver for the child, and may have included one or multiple primary caregivers, including parents, other adult relatives, and foster parents. Clinicians were instructed to designate the type of caregiver impairment that directly impeded the caregiver from providing adequate physical and emotional care for the child. For example, if the clinician obtained information that a caregiver’s mental health as well as alcohol/substance abuse had directly affected their caregiving capacity, a designation of “Both” was made. However, if a co-occurring mental health problem was not reported through interview or record review, and/or it appeared that a caregiver’s mental health had not directly impacted their caregiving capacity, designations of “Mental Illness” or “Both” were ruled out.

In addition to impaired caregiving (ICG), the THP included assessment of a range of trauma types (e.g., abuse, neglect, domestic violence, natural disaster, community violence, and school violence; see Table 2 for a complete listing). Similar to impaired caregiving, standard definitions for each trauma type were provided to staff and were adapted from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Glossary (NCANDS 2000). After collecting comprehensive information for each trauma type, clinicians rated each trauma type as confirmed, suspected, or did not occur. For each trauma type endorsed, clinicians also entered salient details about the trauma (e.g., frequency, perpetrator, setting). The total number of confirmed trauma types was calculated by summing the number of all listed trauma types (including other traumas not otherwise specified) while excluding impaired caregiving (possible range 0–18).

Table 2.

Trauma types for children 7–18 by impaired caregiver group status

| Trauma types | Group 1 No ICG |

Group 2 Alcohol/Drugs Only |

Group MH only |

Group 4 Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2660 | n = 619 | n = 304 | n = 405 | |

| Sexual abuse* | 605 (22.7 %) | 125 (20.2 %) | 70 (23 %) | 133 (32.8 %) |

| Sexual assault | 414 (15.6 %) | 97 (15.7 %) | 54 (17.8 %) | 86 (21.2 %) |

| Physical abuse* | 543 (20.4 %) | 230 (37.2 %) | 110 (36.2 %) | 220 (54.3 %) |

| Physical assault* | 207 (7.8 %) | 72 (11.6 %) | 45 (14.8 %) | 67 (16.5 %) |

| Emotional abuse* | 655 (24.6 %) | 313 (50.6 %) | 144 (47.4 %) | 258 (63.7 %) |

| Neglect* | 263 (9.9 %) | 269 (43.5 %) | 85 (28 %) | 250 (61.7 %) |

| Domestic violence* | 1069 (40.2 %) | 403 (65.1 %) | 160 (52.6 %) | 289 (71.4 %) |

| Illness/Medical trauma* | 214 (8 %) | 68 (11 %) | 38 (12.5 %) | 51 (12.6 %) |

| Serious injury | 293 (11 %) | 89 (14.4 %) | 41 (13.5 %) | 66 (16.3 %) |

| Natural disaster | 174 (6.5 %) | 36 (5.8 %) | 26 (8.6 %) | 29 (7.2 %) |

| Traumatic loss* | 1191 (44.8 %) | 393 (63.5 %) | 168 (55.3 %) | 262 (64.7 %) |

| Interpersonal violence* | 110 (4.1 %) | 42 (6.8 %) | 22 (7.2 %) | 53 (13.1 %) |

| Community violence* | 356 (13.4 %) | 120 (19.4 %) | 59 (19.4 %) | 71 (17.5 %) |

| School violence | 291 (10.9 %) | 86 (13.9 %) | 43 (14.1 %) | 66 (16.3 %) |

| Other trauma | 199 (7.5 %) | 57 (9.2 %) | 35 (11.5 %) | 47 (11.6 %) |

Trauma types are not mutually exclusive

War in/outside U.S., Kidnapping, and Forced Displacement not reported due to few endorsements (<3 %)

Frequencies and percentages are for confirmed trauma exposure types only

* Indicates significant relationship with group distribution at the p < 0.001 level

UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV

The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (PTSD-RI; Steinberg et al. 2004, see also Steinberg et al. 2013) was used to assess PTSD symptoms in school age children and adolescents in the CDS. This instrument assessed the frequency of occurrence of PTSD symptoms during the past month, rated from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (most of the time). The items mapped directly onto DSM-IV symptoms for PTSD. A cut-off score of 38 has demonstrated sensitivity of 0.93 and specificity of 0.87 in detecting PTSD diagnosis (Rodriguez et al. 2001). Previous studies have demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.84; e.g. Roussos et al. 2005). Internal consistency of PTSD-RI in the NCTSN Core Data Set was in the excellent range (α = 0.90 overall and α = 0.86 for this study sample).

Child Behavior Checklist

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) is one of the most widely used instruments of child emotional and behavioral symptoms. The CBCL was completed by a caregiver who knew the child well. This measure consisted of 113 items scored on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (often true) and yielded scores on three scales, Internalizing Behavior Problems (e.g., depression, anxiety), Externalizing Behavior Problems (e.g., aggression), and Total Behavior Problems. Data on reliability and validity of the CBCL have been well established by numerous studies (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). Internal consistency of the CBCL was found to be in the excellent range for children in the NCTSN CDS (α = 0.82 to 0.94 overall and α = 0.90 to 0.93 for this study sample).

Indicators of Functional Impairment

The Indicators of Severity is a CDS-specific measure that assessed 14 domains of functional impairment commonly found in children exposed to trauma. The child’s functioning over the past month prior to the assessment was rated by clinicians on a 3 point scale - 0 (not a problem) to 2 (very much a problem). The current study examined a subset of these indicators in order to obtain additional information about the child’s functioning at home, at school, and within the caregiver-child relationship. The following indicators of severity were analyzed: academic problems, behavior problems at school, behavior problems at home, and attachment problems. Responses were dichotomized and categorized as absent (not a problem) or present (somewhat or very much a problem).

Procedures

As part of routine clinical care, master’s and doctoral-level licensed clinicians completed the baseline CDS forms and standardized measures (e.g., PTSD-RI, CBCL) prior to or at initiation of mental health services. Clinical staff received technical assistance, training, and consultation on the CDS protocol prior to data collection (e.g. technical guides that provided standard definitions and scoring instructions, codebooks, webinars/training videos). NCCTS staff also provided monitoring for quality assurance purposes. To standardize data collection across sites, data were entered into a web-based, electronic data capture system, InForm. Each participating NCTSN center received approval from its Institutional Review Board (IRB) and agreed to the terms set forth in a data use agreement with Duke University. Additional IRB approval was obtained for data collection, data management, and analysis of a de-identified dataset from Duke University Health System and University of California, Los Angeles.

Data Analysis

To address the study aims, relationships between demographics, impaired caregiving, trauma exposure, and emotional/behavioral symptoms (e.g., PTSD, CBCL) were examined. Descriptive analyses were conducted on the demographic characteristics of the sample. We examined whether the presence of any type of impaired caregiving was related to the dependent variables using a conservative definition for endorsement, with impaired caregiving dichotomized as no exposure or suspected exposure = 0 and confirmed exposure = 1. For descriptive comparisons across types of ICG, the sample was divided into four mutually exclusive groups: no impaired caregiving history (Group 1; No ICG), impaired caregiving due to alcohol/substance abuse (Group 2; Alcohol/Drugs Only), impaired caregiving due to mental health problems (Group 3; MH Only), and impaired caregiving due to both mental health problems and alcohol/substance abuse (Group 4; Both).

Bivariate relationships between the impaired caregiver group and categorical variables (e.g., sex, race, guardian) were assessed using chi-square tests for association. Mean differences between continuous variables (e.g., age, number of trauma types) were assessed with a general linear model (either using a Student’s T-Test or ANOVA, as appropriate). General linear mixed models (SAS 9.3 PROC GLIMMIX) were used to determine the significance of the relationship between impaired caregiver grouping and mean PTSD-RI, CBCL Internalizing and Externalizing scores. Generalized mixed models (specifically logistic models) were used to determine the significance of the relationships between impaired caregiver groupings and the likelihood of functional impairments being present. All models were adjusted for center-level random effects that may account for potential correlations around participants nested within centers. Models were also adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and total number of trauma types.

Additional general linear regression models were tested to further characterize the linkages between impaired caregiver status, the number of trauma types experienced, and child symptoms using the PTSD-RI and the CBCL Total Behavior Problems. Specifically, these models were used to determine if the effect of having an impaired caregiver (i.e., on PTSD symptom severity and behavioral problems) was mediated by the number of traumas these youth experienced. The models were also adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity as previously described. Sobel tests were performed to explore the significance of the mediated effect for each of the symptoms examined (PTSD and total behavioral problems).

Results

Demographic characteristics by impaired caregiver (ICG) groups are presented in Table 1 (n = 3988). There were no significant differences between youth with and without ICG on age or sex. Youth with ICG had significantly higher rates of public insurance eligibility. ICG was also significantly related race/ethnicity. Specifically, each of the ICG groups (i.e., Mental Health ICG, Alcohol/Drugs ICG, and Both ICG) had higher proportions of White youth than the No ICG group. Youth in the ICG groups also experienced a higher mean number of total trauma types, with youth in the Both group experiencing about twice as many trauma types on average as youth in the No ICG group (M = 4.9, SD = 2.5 vs. M = 2.5, SD = 1.6).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics for children 7–18 years by impaired caregiver group status (n = 3988)

| Group 1 No ICG |

Group 2 Alcohol/Drugs Only |

Group 3 MH Only |

Group 4 Both |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2660 | n = 619 | n = 304 | n = 405 | |

| Age, M (SD) | 12.4 (3.1) | 12.4 (3.0) | 12.6 (3.1) | 12.8 (3.2) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 1227 (46.1 %) | 259 (41.8 %) | 127 (41.8 %) | 164 (40.5 %) |

| Female | 1433 (53.9 %) | 360 (58.2 %) | 177 (58.2 %) | 241 (59.5 %) |

| Race/Ethnicity* | n = 2604 | n = 611 | n = 300 | n = 398 |

| White | 703 (27.0 %) | 272 (44.5 %) | 146 (48.7 %) | 232 (58.3 %) |

| Black | 714 (27.4 %) | 124 (20.3 %) | 58 (19.3 %) | 57 (14.3 %) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1054 (40.5 %) | 166 (27.2 %) | 80 (26.7 %) | 76 (19.1 %) |

| Other | 133 (5.1 %) | 49 (8.0 %) | 16 (5.3 %) | 33 (8.3 %) |

| Eligible for public insurance* | 1473 (55.3 %) | 474 (76.5 %) | 220 (72.3 %) | 319 (78.7 %) |

| Primary residence* | n = 2398 | n = 602 | n = 302 | n = 404 |

| With parents | 1880 (78.4 %) | 300 (49.8 %) | 212 (70.2 %) | 156 (38.6 %) |

| With relatives | 241 (10.1 %) | 151 (25.1 %) | 24 (8.0 %) | 84 (20.8 %) |

| Foster care | 106 (4.4 %) | 79 (13.1 %) | 23 (7.6 %) | 87 (21.5 %) |

| Other | 171 (7.1 %) | 72 (12.0 %) | 43 (14.2 %) | 77 (19.1 %) |

| Guardian* | n = 2425 | n = 603 | n = 302 | n = 402 |

| Parent | 2030 (83.7 %) | 346 (57.4 %) | 236 (78.2 %) | 187 (46.5 %) |

| Relative | 193 (8.0 %) | 112 (18.6 %) | 20 (6.6 %) | 71 (17.7 %) |

| State | 124 (5.1 %) | 115 (19.1 %) | 37 (12.3 %) | 121 (30.1 %) |

| Other | 78 (3.2 %) | 30 (5.0 %) | 9 (3.0 %) | 23 (5.4 %) |

|

Total Number of Trauma Types* (M, SD) |

2.5 (1.6) | 3.9 (2.2) | 3.7 (2.2) | 4.9 (2.5) |

* Indicates significant relationship with group distribution at the p < 0.001 level

Type of ICG was also significantly related to primary residence and guardianship. There were higher proportions of youth in the No ICG group (78.4 % and 83.7 %) and the Mental Health ICG group (70.2 % and 78.2 %) living at home with and in the custody of their parents, respectively. Conversely, there were higher proportions of youth in the Alcohol/Drugs ICG group (25.1 % and 18.6 %) and the Both ICG group (20.8 % and 17.7 %) living at home with and in the custody of a relative caregiver. Youth in the Both ICG group also endorsed much higher rates of foster care placement and other types of living situations (e.g., residential treatment center, correctional facility).

With regard to hypothesis 1, ICG was significantly associated with confirmed exposure to all forms of intra-familial trauma, including: sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, and domestic violence, as well as traumatic loss/separation/bereavement. ICG was also significantly related to exposure to some extra-familial trauma types, including physical assault, interpersonal violence, and community violence. For each of these trauma types, the Both ICG group had much higher rates of exposure than the Alcohol/Drugs ICG group and Mental Health ICG groups. Additional details on trauma types by ICG groups are presented in Table 2.

With regard to hypothesis 2, emotional symptoms, behavioral problems, and functional impairments by ICG group are presented in Table 3. ICG was significantly related to the PTSD-RI severity score in a manner consistent with increasing severity across ICG groups; the No ICG group had the lowest mean total score (M = 26.4; SD = 14.8), while the Both ICG group had the highest mean total score (M = 29.1; SD = 14.7). When these differences are modeled adjusting for age, gender, and ethnicity, these effect sizes remain moderate to large (absolute values from 0.7 to 1.3). ICG was also significantly related to CBCL Total Behavior scores, but in a slightly different pattern, with the Alcohol/Drugs ICG and No ICG groups having lower mean scores (M = 63.5; SD = 10.2, and M = 62.2; SD = 10.7) and the Mental Health ICG and Both groups having higher mean scores (M = 65.9; SD = 9.5 and M = 66.1; SD = 9.2). Results were similar with respect to CBCL Internalizing scores, with the Alcohol/Drugs ICG and No ICG groups having lower mean scores (M = 61.6; SD = 11.0, and M = 61.8; SD = 11.4) and the Mental Health ICG and Both groups having higher mean scores (M = 65.2; SD = 10.7 and M = 64.4; SD = 10.3). Modeling these differences with similar adjustments show fairly large effect sizes (absolute values from 1.1 to 5.1). There were no significant differences in CBCL Externalizing scores.

Table 3.

Frequencies and modeled results of child mental health symptoms and functional impairments by impaired caregiver group

| Group 1 No ICG |

Group 2 Alcohol/Drugs Only |

Group 3 MH Only |

Group 4 Both |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2660 | n = 619 | n = 304 | n = 405 | |

| PTSD-RI total, M (SD)* | 26.4 (14.8) | 26.7 (14.6) | 27.9 (14.4) | 29.1 (14.7) |

| Effect | – | −0.71 | 0.84 | 1.3 |

| CBCL internalizing* | 61.8 (11.4) | 61.6 (11.0) | 65.2 (10.7) | 64.4 (10.3) |

| Effect | – | −1.68 | 1.91 | 4.43 |

| CBCL externalizing | 61.4 (11.2) | 63.3 (10.7) | 64.4 (10.2) | 64.7 (10.0) |

| Effect | – | 2.79 | 3.05 | 4.11 |

| CBCL total * | 62.2 (10.7) | 63.5 (10.2) | 65.9 (9.5) | 66.1 (9.2) |

| Effect | – | 1.19 | 3.84 | 5.08 |

| Academic problems, n, (%) | 1375 (58.0 %) | 326 (58.6 %) | 159 (62.4 %) | 228 (66.3 %) |

| Odds ratio | – |

1.1 (0.91, 1.33) |

1.49 (1.17, 1.89) |

1.41 (1.08, 1.83) |

| Attachment problems* | 795 (43.4 %) | 272 (48.6 %) | 125 (49.0 %) | 215 (61.3 %) |

| Odds ratio | – |

1.86 (1.53, 2.25) |

2.88 (2.27, 3.65) |

2.18 (1.69, 2.81) |

| Behavior problems at home* | 1051 (44.4 %) | 268 (48.1 %) | 134 (52.6 %) | 206 (60.1 %) |

| Odds ratio | – |

1.57 (1.29, 1.92) |

1.53 (1.2, 1.96) |

2.11 (1.6, 2.78) |

| Behavior problems at school* | 1341 (56.4 %) | 375 (66.9 %) | 185 (72.6 %) | 239 (69.3 %) |

| Odds ratio | – |

1.26 (1.04, 1.53) |

1.84 (1.46, 2.34) |

1.68 (1.3, 2.17) |

Effects and Odds Ratios use No ICG group as reference

Additionally, with regard to functional impairment indicators, the likelihood of reporting Attachment Problems was significantly related to ICG, once again demonstrating a pattern of increased frequency by type of ICG; the lowest frequency of problems was in the No ICG group (43.4 %) and the highest frequency was in the Both ICG group (61.3 %), with the Alcohol/Drugs ICG group (48.6 %) and Mental Health ICG group (49.0 %) falling in the middle. Similarly, Behavior Problems at Home was significantly related to ICG and followed the same pattern, with the No ICG group having the lowest frequency (44.4 %), the Both ICG group having the highest frequency (60.1 %), and the Alcohol/Drugs ICG (48.1 %) and Mental Health IGG (52.6 %) groups falling in the middle. Similar to patterns on the CBCL Internalizing Scale, Behavior Problems at School was the least frequent for the No ICG group (56.4 %), and the most frequent for the Mental Health ICG group (72.6 %). There were no significant differences observed for Academic Problems.

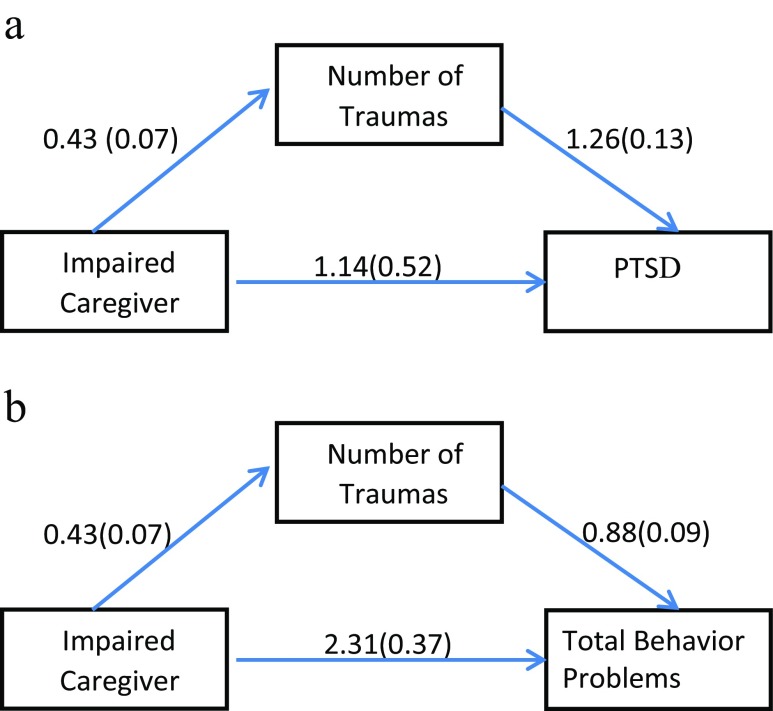

With regard to hypothesis 3, the results for the models used to determine if the effect of having an impaired caregiver on child PTSD and total behavioral problems was mediated by the number of traumas youth experienced are presented in Fig. 1a and b. Mediation is generally said to occur when (1) the IV significantly affects the mediator, (2) the IV significantly affects the DV in the absence of the mediator, (3) the mediator has a significant unique effect on the DV, and (4) the effect of the IV on the DV decreases upon the addition of the mediator to the model. Each of these conditions was met. Additionally, Sobel test statistics were greater than 5 and p-values were less than 0.001. Together, these results suggest that the tested mediator (number of trauma types experienced) was statistically significant for both PTSD symptoms and total behavioral problems.

Fig. 1.

a. Mediation model for impaired caregiver, total number of traumas, and PTSD symptom severity. b. Mediation model for impaired caregiver, total number of traumas, and behavioral problems (CBCL Total)

Discussion

The results of this study underscored that exposure to impaired caregiving is highly common for trauma-exposed youth. Endorsement of caregiver impairment due to alcohol/drug problems was substantially higher than impairment due to mental health problems. This finding may be due in part to the under-identification of caregiver mental illness, given the general absence of routine caregiver screening in child service settings. Conversely, it may also reflect a true difference in prevalence rates between mental illness and alcohol/drug use among primary caregivers. National data on frequency of caregiver mental illness are largely unavailable, and as a result, existing programs often fail to address caregiver mental health from a dyadic or caregiver-child perspective (Nicholson et al. 2002). Future research should focus on systematically identifying caregiver mental illness and examine the benefits of coordinated services that support families and reduce stigmatization.

Although not included in the study hypotheses, important differences in child placement were identified according to caregiver impairment history. The majority of children that have a caregiver with mental health problems were living with and in the custody of a parent at the time of data collection, at comparable rates to children with a caregiver with no history of impairment. Youth of caregivers with mental health problems, however, had significantly higher rates of trauma exposure and psychosocial problems. This finding highlights the importance of proactively and routinely addressing caregiver mental health and how it may affect the caregiver-child relationship. Expanding programs such as home visiting (Ammerman et al. 2010; Guterman 2001) and parent-inclusive early childhood education (Administration on Children Youth and Families 2002) are critical steps toward addressing the sequelae associated with caregiver functioning.

Consistent with the study hypotheses, youth of impaired caregivers had significantly higher number of trauma types, both overall and within every type of intra-familial trauma assessed. Rates of trauma exposure also varied across types of ICG, and were most pronounced for youth with multiple forms of impaired caregiving. Youth with multiple forms of ICG experienced five types of trauma on average, which was twice the rate of youth without impaired caregiving, placing these youth at significant risk for long-term health and mental health problems and related disparities (Anda et al. 2006). In addition, impaired caregiving was also associated with community and interpersonal violence exposure outside of the family context. This pattern may reflect higher levels of environmental risk for ICG-affected youth, cumulative risk for violence exposure over time (Margolin et al. 2010), or reduced capacity of caregivers with mental health and alcohol/drug problems to provide adequate protection for their children in high-risk communities. Rates of other trauma types, such as sexual and physical assault, injury, and natural disaster, did not significantly vary according to impaired caregiving status, indicating that ICG may not be directly implicated in exposure to these types of child trauma. Overall, these results point to the far-reaching consequences of ICG on youth developmental trajectories. Future research should focus on identifying longitudinal mechanisms that may place ICG-affected youth on paths toward poly-victimization across childhood and adolescence.

Results indicated that ICG is uniquely associated with several areas of youth psychosocial functioning compared to youth without ICG histories. There were moderate to large significant associations between ICG and several areas of child psychosocial functioning, including child PTSD symptom severity, internalizing problems, attachment problems, and behavioral problems at home and school, after accounting for child age, sex, race/ethnicity, total number of trauma types experienced, and the site at which the child was assessed. Results were not significant for academic and externalizing problems after accounting for the aforementioned covariates (i.e., demographics and total number of trauma types). Additionally, across all domains, some descriptive differences were found between types of caregiver impairment. Youth of caregivers with mental health problems (co-occurring with alcohol/substance use or in isolation) showed mildly elevated scores compared to youth of caregivers with alcohol/drug problems or no impairment. Although these results are descriptive and preliminary, and existing literature in this area is sparse, there are several potential explanations for this finding which should be the focus of future research. First, it is possible that the experience of living with a caregiver with mental health problems is qualitatively different than living with a caregiver with alcohol/drug problems (Aldridge 2006) and requires different types of adjustment and coping from children. For example, in addition to providing instrumental support for daily routines (e.g., cooking meals, household chores), children of caregivers with mental health problems may also be required to provide increased emotional support for the family (e.g., responding to psychiatric crises and continuously monitoring a caregiver’s emotional health status). Future research should focus on understanding these differences empirically, and how they may relate to different symptom profiles in children and adolescents.

Lastly, results of the current study support a meditational model for the number of child trauma types as a mechanism between impaired caregiving and child PTSD and behavioral problems. Interpreted in the context of existing maltreatment literature, which has established young child age and caregiver impairment as risk factors for maltreatment (CDC 2011), the results of this study suggest that ICG contributes to risk for multiple trauma exposures beyond abuse and neglect, resulting in long-term psychosocial difficulties during childhood. Prevention of child trauma exposure among families with impaired caregivers should be a primary target for reducing psychosocial problems among youth. In order to accomplish this objective, the field must shift its approach away from individually-focused service delivery, toward two-generation approaches to mental health treatment. Implications of this approach would at minimum include co-location of services for caregivers and children within a family-focused clinic and communication between adult and child providers throughout treatment.

Despite these important findings, this study also had several limitations. The NCSTN Core Data Set is a quality improvement initiative that includes a sample of youth referred for trauma-focused mental health services at clinics within the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Consequently, the sample is not nationally representative of U.S. youth, or clinic-referred youth seen for reasons other than trauma exposure. Additionally, specific details on caregiver impairment were not available (e.g., specific diagnosis of caregiver, severity, and course). These details are important to consider in conceptualizing, designing, and analyzing investigations of caregiver impairment, and they should be addressed in future studies. Moreover, the primary measure of child behavior in this study was a parent-report form, and the relationship between certain types of caregiver mental health problems and accurate reporting of child symptoms has been debated in the literature (Gartstein et al. 2009; Richters 1992). Caregiver reporting accuracy may also vary according to whether children are residing with their parent, a relative, or in foster care/residential placement. Lastly, this study is limited to associations between impaired caregiving and other forms of trauma without examining the temporal order over time of these experiences. While youth may have been exposed to other forms of trauma prior to their caregivers being impaired, previous studies of the NCTSN CDS have demonstrated that impaired caregiving has one of the earliest ages of onset of the trauma types assessed by the Trauma History Profile (Pynoos et al. 2014). Approximately 80 % of youth in the CDS with a history of exposure to impaired caregiving had an onset of exposure prior to age five.

Building adult capacity to support and nurture children, beginning in pregnancy and early childhood, is a key driver for public health promotion (Shonkoff and Phillips 2000). Shifting the field’s approach from individually-focused adult interventions for caregiver mental illness and alcohol/substance abuse to a dyadic or family-focused approach may convey increased benefits for healthy family functioning (Wells and Fuller 2000). Promoting safe, stable, and nurturing parent-child relationships (CDC 2009), particularly for the most vulnerable families, should be a primary focus for medical and mental health providers serving clients across the lifespan.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This manuscript was developed (in part) under grant numbers 2U79SM054284 and SM061256 from the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The views, policies, and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of SAMHSA or HHS. We would like to acknowledge the 56 sites within the NCTSN that have contributed data to the Core Data Set as well as the children and families that have contributed to our growing understanding of child traumatic stress.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Rebecca Vivrette declares that she has no conflict of interest. Ernestine Briggs declares that she has no conflict of interest. Robert Lee declares that he has no conflict of interest. Krista Kenney declares that she has no conflict of interest. Tina Houston-Armstrong declares that she has no conflict of interest. Robert Pynoos declares that he has no conflict of interest. Laurel Kiser declares that she has no conflict of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Centre for Children, Youth and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Administration on Children Youth and Families . Making a difference in the lives of children and families: The impacts of Early Head Start Programs on infants and toddlers and their families. Washington: Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge J. The experiences of children living with and caring for parents with mental illness. Child Abuse Review. 2006;15:79–88. doi: 10.1002/car.904. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman RT, Putnam FW, Bosse NA, Teeters AR, Van Ginkel JB. Maternal depression in home visitation: a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2010;15:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J.D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., . . . & Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: a convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256, 174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Appleyard K, Egeland B, van Dulmen MHM, Sroufe LA. When more is not better: the role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Pathways from child maltreatment to internalizing problems: perceptions of control as mediators and moderators. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:913–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau, N., Chilcoat, H. D., Kessler, R. C., & Davis, G. C. (2014). Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). Child maltreatment: Risk and protective factors. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/childmaltreatment/riskprotectivefactors.html.

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2009). Preventing child maltreatment through the promotion of safe, stable, and nurturing relationships between children and caregivers. Atlanta, GA. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/efc-01-03-2013-a.pdf.

- Chaffin M, Kelleher K, Hollenberg J. Onset of physical abuse and neglect: psychiatric, substance abuse, and social risk factors from prospective community data. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20(3):191–203. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(95)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E. Child abuse and neglect and the development of mental disorders in the general population. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:981–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello J. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:377–384. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Anda RF, Dube SR, Dong M, Chapman DF, Felitti VJ. The wide-ranging health consequences of adverse childhood experiences. In: Kendall-Tackett K, Giacomoni S, editors. Victimization of children and youth: Patterns of abuse, response strategies. Kingston: Civic Research Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: a neglected component in child victimization trauma. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, Theodore A, English DJ, Black MM, Wike T, Whimper L, Runyan DK, Dubowitz H. Effect of early childhood adversity on health. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:1232–1238. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, Frueh BC. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and sub- stance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(6):545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay V, Oatis MD, Silva RR, Hirsch G. Epidemiological aspects of PTSD in children and adolescents. In: Silva RR, editor. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: Handbook. New York: Norton; 2004. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Bridgett DJ, Dishion TJ, Kaufman NK. Depressed mood and maternal report of child behavior problems: another look at the depression–distortion hypothesis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30(2):149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Stein MB. Association between childhood trauma and physical disorders among adults in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34(3):509–520. doi: 10.1017/S003329170300134X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterman N. Stopping child maltreatment before it starts: Emerging horizons in early home visitation services. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01157-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney CA, Wechsler A, Kaur H, Lemos-Miller A. Posttraumatic stress disorder in maltreated youth: a review of contemporary research and thought. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13:46–76. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl PL, Johnson-Reid M, Drake B. Maternal mental illness and the safety and stability of maltreated children. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2011;35:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Olino TM, Klein DN. Psychosocial impairments in offspring of depressed parents. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:1493–1503. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Vickerman KA, Oliver PH, Gordis EB. Violence exposure in multiple interpersonal domains: cumulative and differential effects. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;47:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies (2009). The NSDUH report: Children living with substance dependent or substance abuse parents: 2002 to 2007. Rockville.

- Morgan PT, Desai RA, Potenza MN. Gender-related influences of parental alcoholism on the prevalence of psychiatric illnesses: analysis of the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(10):1759–1767. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustillo SA, Dorsey S, Conover K, Burns BJ. Parental depression and child outcomes: the mediating effects of abuse and neglect. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(1):164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00796.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS). Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2000). NCANDS Glossary. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/systems/ncands/ncands98/glossary/glossary.pdf.

- Nicholson, J., Biebel, K., Katz-Leavy, J., & Williams, V. (2002). The prevalence of parenthood in adults with mental illness: Implications for state and federal policymakers, programs, and providers. Psychiatry Publications and Presentations, 153. Retrieved from http://escholarship.umassmed.edu/psych_pp/153.

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Alan Pincus H, Weissman M. Parental depression, child mental health problems, and health care utilization. Medical Care. 2003;41(6):716–721. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000064642.41278.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, Berger LM. Parental substance abuse and child well-being a consideration of parents’ gender and coresidence. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30(3):341–370. doi: 10.1177/0192513X08326225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos, R. S., Steinberg, A. M., Layne, C. M., Liang, L., Vivrette, R. L. Kisiel, C., . . . & Belin, T. (2014). Modeling constellations of trauma history in the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Data Set. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(S1), S9–S17.

- Richters J. Depressed mothers as informants about their children: a critical review of the evidence for distortion. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:485–499. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, N., Steinberg, A. M., Saltzman, W., & Pynoos, R. S. (2001). The PTSD index: Psychometric analysis of the adolescent version. Paper presented at the 17th Annual Conference of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, New Orleans, LA.

- Roussos, A., Goenjian, A. K., Steinberg, A. M., Sotiropoulou, C., Kakaki, M., Kabakos, C., … & Manouras, V. (2005). Posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among children and adolescents after the 1999 earthquake in Ano Liosia, Greece. AJP, 162(3), 530–537. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sameroff A, Gutman LM, Peck SC. Adaptation among youth facing multiple risks: Prospective research findings. In: Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 364–391. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA, editors. From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington: National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., McGuinn, L., … & Wood, D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–e246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer M, Decker K, Pynoos RS. The UCLA PTSD reaction index. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2004;6:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Kim S, Briggs EC, Ippen CG, Ostrowski SA, Gully KJ, Pynoos RS. Psychometric properties of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index: Part I. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.21780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: the varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:957–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman MWM, Browne KD. Three decades of child maltreatment research: implications for the school years. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2001;2(3):215–239. doi: 10.1177/1524838001002003002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wells SJ, Fuller T. Elements of best practice in family centered services. Urbana: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; 2000. [Google Scholar]