Abstract

Efficacy of EMDR and TF-CBT for posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) was explored through meta-analysis. A comprehensive search yielded 494 studies of children and adolescents with PTSS who received treatment with these evidence-based therapeutic modalities. Thirty total studies were included in the meta-analysis. The overall Cohen’s d was small (−0.359) and statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating EMDR and TF-CBT are effective in treating PTSS. Major findings posit TF-CBT is marginally more effective than EMDR; those with sub-clinical PTSS responded more favorably in treatment than those with PTSD; and greater reductions in PTSS were observed with presence of comorbidity in diagnosis. Assessment of publication bias with Classic fail-safe N revealed it would take 457 nonsignificant studies to nullify these findings.

Keywords: Eye movement and desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), Effectiveness, Posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Meta-analysis, Children, Adolescents

Childhood is a critical time for social, emotional, and psychological development, all of which can be impaired by trauma (Kessler et al. 1995). The experience of trauma during childhood not only impacts one’s immediate functioning, but can affect long-term functioning as well. Despite the impact trauma can have on short- and long-term functioning, estimates indicate that only a small percentage (i.e., 16 or 17%) of adolescents with mental health symptoms receive needed treatment (Helland and Mathiesen 2009; Rolfsnes and Idsoe 2011). Research shows this lack of access to treatment leads to increased risk of developing a range of mental disorders, including personality disorders such as Borderline Personality Disorder (Howe 2005). These findings highlight the importance of providing adequate and early treatment of PTSS (Lenz and Hollenbaugh 2015).

The past two decades have seen the development of several evidence-based psychological treatments for PTSS. The current study focuses on the comparative effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) treatments. Current literature demonstrates the effectiveness of these treatments for children and adolescents (Chemtob et al. 2002; Cohen et al. 2004a; Puffer et al. 1998). The current meta-analysis is the first to directly compare studies on the effectiveness of the two leading evidence-based treatments for childhood PTSS.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR is a manualized treatment developed by Francine Shapiro to treat trauma in as little as one 90-minute session (Shapiro 1989a; Shapiro 1989b). The initial stage of the EMDR protocol consists of taking a history of the individual’s traumatic past, understanding the current trauma symptoms, and helping the individual cope with past trauma (Shapiro 2001). The protocol contains both exposure and cognitive components; for example, clients are guided through a relaxation exercise to assist them in visualizing a “safe place” (Ahmad and Sundelin-Wahlsten 2008) and asked to visualize aspects of the trauma and replace negative thoughts with positive ones (Adler-Nevo and Manassis 2005). A main feature of EMDR is having clients move their eyes rapidly while focusing on the traumatic memory until the level of distress decreases (Shapiro 2007). As clients are asked to rate subjective units of distress (SUD) and validity of the positive cognition (VOC), they are also encouraged to share negative thoughts associated with the traumatic event and use a positive cognition to replace the negative thoughts. The session ends with reengaging in the “safe place” exercise (Ahmad and Sundelin-Wahlsten 2008).

According to the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies’ current treatment guidelines, EMDR is designated as an effective treatment for PTSD (Foa et al. 2009). Although eye movements are an established part of its procedure, some researchers have argued that they are not necessary and that EMDR is best understood as an exposure technique (Davidson and Parker 2001; Foa and Meadows 1997; Foley and Spates 1995; Lohr et al. 1995; Lohr et al. 1998; Sanderson and Carpenter 1992). There has been more research conducted on the effectiveness of EMDR treatment for trauma symptoms with adult samples than with children and adolescents (Davidson and Parker 2001), and researchers have proposed developmentally-appropriate adjustments to the protocol for use in child clients. Greenwald (1999), Lovett (1999), and Tinker and Wilson (1999) were among the first to introduce and demonstrate valuable aspects of EMDR for treatment of children. Ahmad and Sundelin-Wahlsten (2008), who published one of the first randomized control trials examining the effects of child-adjusted modifications, described incorporating modifications such as including caregivers in sessions and using hand-tapping or finger clicks near the child’s ears in lieu of eye movements. Face-pictures can be used as a concrete tool for rating distress and cognition validity if the child has difficulty using the adult rating scales for SUDs and VOCs. Such modifications permit therapists to adapt the existing protocol to be developmentally appropriate for children.

Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT)

TF-CBT is a psychotherapy approach that was developed in 1996 by Cohen, Mannarino, and Deblinger to treat children and adolescents experiencing traumatic symptoms in as few as 12 sessions. Children are taught a variety of cognitive, behavioral and physiological techniques that they can use outside of session to regulate emotions. Children are encouraged to develop a trauma narrative that gradually tells the story of what occurred during their traumatic experience, often writing it down (Cohen and Mannarino 2008), however therapists can adapt the exposure intervention to focus on play or artistic expression in place of a formal written narrative. Common adaptations include acting out the trauma with puppets, creating a scrapbook with drawings and photos, or engaging in songwriting (Cavett and Drewes 2012). TF-CBT also enhances effective family communication, parenting skills, growth, and safety. The parent-training component teaches caregivers to manage their own emotional response to the traumatic event in order to assist the child with emotional regulation. Focus is also placed on enhancing their parenting skills and to learn ways to support their child, which could lead to increased treatment success for their children (Weiner et al. 2009).

Research has demonstrated TF-CBT is superior to supportive therapy for young children who have experienced sexual abuse (Cohen and Mannarino 1996; Cohen and Mannarino 1998). This treatment modality has been effective in treating children suffering from PTSD, anxiety, depression, externalizing and/or sexualized behaviors, and feelings of mistrust and shame as a result of traumatic life events (Weiner et al. 2009) and assists the child and their parents in establishing new skills to manage distressing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Research has also shown greater increases in effective parenting practices and fewer externalizing child behavioral problems post TF-CBT treatment (Deblinger et al. 2011). Additionally, TF-CBT can be used effectively in a variety of settings (Child Welfare Information Gateway 2012) and has been modified for use with many different populations (Black et al. 2012; Little and Akin-Little 2009). More recent literature has shown that, regardless of the number of sessions employed, the trauma narrative component seemed to be the most effective means of ameliorating parents’ distress and children’s anxiety (Deblinger et al. 2011).

Review of Meta-Analyses

Children and Adolescents

Findings from available meta-analyses and systematic reviews are summarized in Table 1. Similar to the studies with adult samples, traditional CBT and EMDR have been found to be most effective in reducing trauma symptoms for children and adolescents. Conversely, a single randomized control trial directly compares the two leading treatments, TF-CBT and EMDR, to determine which is more effective for children and adolescents (Diehle et al. 2015). In this study, 48 children aged eight to 18 were randomly assigned to eight sessions of either EMDR or TF-CBT. PTSS was monitored via the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Children and Adolescents (CAPS-CA). Both treatments showed large reductions in PTSS; the difference in reduction between the two treatments was small and not statistically significant. As such, determining the treatment technique that is most effective is an area in need of more research.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Reviewed Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews on Treatment of PTSD/PTSS for Children and Adolescents

| Meta-Analysis/Systematic Review | N Studies | Intervention(s) | Trauma Type(s) | Diagnosis | Effect Size (g) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silverman et al. (2008) | 21 |

TF-CBT School-based group CBT Individual CBT Resilient peer treatment CPT EMDR Family therapy Client-centered therapy |

Sexual abuse Physical abuse Community violence Hurricane exposure Witness to marital violence Motor vehicle accident |

PTSS PTSD |

.43 | Possibly efficacious treatments included EMDR, client-centered therapy, family therapy, child-parent psychotherapy, and CBT for PTSD |

| Rodenburg et al. (2009) | 7 |

EMDR CBT treatments |

Sexual abuse Hurricane Firework disaster |

PTSS | .56 | EMDR was significantly more effective in treating symptoms compared to other treatments and controls. EMDR was found to be incrementally more effective than CBT. |

| Harvey and Taylor (2010) | 39 |

TF-CBT Play therapy Supportive counseling EMDR |

Sexual abuse | PTSS | 1.12 | Cognitive-behavioral treatments were found to produce the largest effect sizes compared to insight-oriented, eclectic, and other therapies. |

| Puttre (2011) | 67 |

CBT TF-CBT School-based CBT EMDR Child-centered play therapy |

Sexual abuse War/Refugee |

PTSS | .83 | Although TF-CBT had the largest effect size of the treatments reviewed, it was not significantly different from the other therapies. |

| Kowalik et al. (2011) | 8 | CBT | Sexual abuse | PTSS | – | CBT was effective in the treatment of children with PTSS. In particular, Total Problems, Internalizing, and Externalizing of the CBCL showed favorable outcomes reflected by greater effect sizes of the CBT treatment groupsversus comparison groups. |

| Rolfsnes and Idsoe (2011) | 19 |

Individual or group CBT Group play/art therapy Group mind/body techniques Individual EMDR |

Political conflict Community violence Hurricane Tsunami Earthquake World Trade Center attacks Refugees/asylum-seekers War |

PTSS | .68 | The most common treatment approach, CBT, was found to be largely effective in relation to the programs reviewed. Many of these studies also had effect sizes in the medium to large range in relation to co-morbid symptoms (e.g., depression and anxiety). |

| Cary and McMillen (2012) | 10 | TF-CBT |

Sexual abuse Intimate partner violence Life threatening traumatic event |

PTSS | .671 | TF-CBT was effective in reducing PTSS, depression, and behavior problems. |

| Greyber et al. (2012)a | 5 | EMDR |

Domestic violence Sexual abuse Emotional/physical abuse Motor vehicle accident |

PTSD | – | Four out of five studies included showed a reduction in PTSS for those who received EMR, regardless of age, gender, and the number of sessions provided. |

| de Arellano et al. (2014)a | 16 | TF-CBT |

Sexual abuse Hurricane exposure Intimate-partner violence Mixed trauma War exposure |

PTSS | – | In comparison to controls, TF-CBT groups showed consistent pre- to posttreatment decreases in PTSS, and these improvements were sustained at follow-up periods of up to 12 months. |

| Lenz and Hollenbaugh (2015) | 21 | TF-CBT |

Sexual assault Abuse/neglect Multiple types Terrorism War related Natural disaster |

PTSD | −1.48 | TF-CBT was found to be effective in treating the symptoms of PTSD and co-occurring depression among childrenand adolescents when compared to no treatment or alternative treatments. |

Note. Studies are listed in chronological order

aSystematic Review

N Studies, Total number of studies examined within meta-analysis or systematic review. TF-CBT, Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. CBT, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. CPT, Cognitive Processing Therapy. EMDR, Eye Movement and Desensitization Reprocessing. PTSS, Posttraumatic stress symptoms. PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. CBCL, Child Behavioral Checklist

The World Health Organization (2013) has developed guidelines related to the management of conditions related to stress. More specifically, TF-CBT and EMDR are the only psychotherapies that are recommended for children and adolescents with PTSD. While studies have found both modalities to be effective in treating PTSS, research to date has not yet determined which of these treatments is superior. As such, the rationale for conducting the present exploratory study was three-fold: to (a) investigate the effectiveness of these two leading treatments on posttraumatic stress symptoms specifically in children and adolescents, (b) determine potential differences in treatment effectiveness between EMDR and TF-CBT, and (c) identify relevant factors that may have an impact upon treatment delivery and its relative effectiveness. It should be noted that this meta-analysis serves as the first of its kind to directly compare the evidence base for EMDR and TF-CBT for treating trauma symptoms in youth.

Method

Study Selection

This meta-analysis investigated the relationship between EMDR and TF-CBT as it relates to PTSS in children and adolescents. Therefore, all studies that utilized these modalities as treatment for posttraumatic stress symptoms were considered for inclusion in this meta-analysis. An extensive literature search was conducted examining the EbscoHOST database, which encompassed a total of 29 electronic databases (e.g., PsycINFO and Medline; see Appendix Table 5). Studies were selected using the search terms: eye movement desensitization and reprocessing or EMDR, trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy or TF-CBT, posttraumatic stress or PTSD, child* or adolesc*, and effect*. In addition, a timeframe delimiter of searching for articles from 1989 until 2015 was incorporated due to the inception of EMDR in 1989. Reference lists of studies reviewed were then examined for any additional studies not identified in the initial search. A total of 471 studies were identified after deletion of duplicates.

Table 5.

Comprehensive List of All Databases Used in the Meta-Analysis

| Academic Search Premier | |

| AHFS Consumer Medication Information | |

| Alt HealthWatch | |

| Business Source Complete | |

| eBook Collection (EBSCOhost) | |

| Education Research Complete | |

| ERIC (Education Resource Information Center) | |

| Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia | |

| GreenFILE | |

| Health and Psychosocial Instruments | |

| Health Source – Consumer Edition | |

| Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition | |

| LGBT Life with Full Text | |

| Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts | |

| MAS Ultra – School Edition | |

| MEDLINE with Full Text | |

| Mental Measurements Yearbook with Tests in Print | |

| Military & Government Collection | |

| Newspaper Source | |

| PEP Archive | |

| Primary Search | |

| PsycARTICLES | |

| PsycBOOKS | |

| PsycCRITIQUES | |

| PsycEXTRA | |

| PsycINFO | |

| PsycTESTS | |

| Regional Business News | |

| SocINDEX with Full Text |

Criteria for inclusion in this meta-analysis were as follows: (a) included children or adolescents between the ages of 3 and 18 who had experienced some form of traumatic event, (b) involved TF-CBT or EMDR modalities as treatments, (c) had sufficient data to calculate an effect size, (d) had an outcome measure of PTSS, and (e) was written in English. Studies that were excluded were as follows: (a) inclusion of adults, (b) focus of treatment for symptoms other than PTSS (e.g., conduct disorder or depression), and (c) were written in languages other than English. Abstracts of prospective articles were initially screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies that met criteria or those that a determination could not be made were then reviewed in full text. Of the 471 studies identified, 441 were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria. More specifically, studies excluded were reviews or non-research (213), those that did not include EMDR or TF-CBT (68), those classified as proposed research or were not accessible (55), case studies (45), those utilizing adults (35), those investigating mental health disorders other than PTSS (13), qualitative studies (6), those published in languages other than English (5), and those for which an effect size could not be calculated (1). Thus, the 30 remaining studies were used in the present analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Reviewed Studies, Treatment N, Treatment Group, Comparison Group, Diagnosis, Comorbidity, Trauma Type, Complex Trauma, and Percentage of Girls in Sample

| Study | Treatment N | Treatment | Comparison | Diagnosis | Comorbidity | Trauma Type | Complex Trauma % | Girls % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad et al. (2007) | 17 | EMDR | WAIT LIST | PTSD | YES | MIXED | <50 | 58.8 |

| Chemtob et al. (2002) | 17 | EMDR | OTH | PTSD | UNK | SINGLE | NONE | 68 |

| Cohen et al. (2004a) | 114 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSS | UNK | SINGLE | >50 | 79 |

| Cohen et al. (2011) | 64 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 54 |

| Cohen et al. (2004b) | 22 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | <50 | 50 |

| Costantino et al. (2014) | 76 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSS | UNK | SINGLE | NONE | UNK |

| Damra et al. (2014) | 9 | TF-CBT | NO TX | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 0 |

| Diehle et al. (2015) | 23 | TF-CBT | EMDR | PTSS | YES | MIXED | <50 | 61 |

| Hebert and Daignault (2015) | 17 | TF-CBT | OTH | UNK | UNK | SINGLE | <50 | 60 |

| Jaberghaderi et al. (2004) | 9 | EMDR | OTH | PTSS | UNK | SINGLE | <50 | 100 |

| Jaycox et al. (2010) | 60 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSD | NO | SINGLE | >50 | 63 |

| Jensen et al. (2014) | 79 | TF-CBT | TAU | PTSS | YES | MIXED | >50 | 79.5 |

| Kemp et al. (2010) | 13 | EMDR | WAIT LIST | PTSS | NO | SINGLE | NONE | 23.1 |

| Konanur and Muller (2012) | 58 | TF-CBT | NO TX | PTSS | UNK | SINGLE | >50 | 70.8 |

| Layne et al. (2001) | 87 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 81 |

| Madigan et al. (2015) | 21 | TF-CBT | TAU | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 100 |

| McMullen et al. (2013) | 25 | TF-CBT | WAIT LIST | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 0 |

| Murray et al. (2013) | 94 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSD | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 50 |

| O'Callaghan et al. (2013) | 24 | TF-CBT | WAIT LIST | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 100 |

| O'Donnell et al. (2014) | 64 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 50 |

| Oras et al. (2004) | 13 | EMDR | OTH | PTSD | NO | MIXED | >50 | 76.9 |

| Ormhaug et al. (2014) | 79 | TF-CBT | TAU | PTSS | YES | MIXED | >50 | 79.5 |

| Puffer et al. (1998) | 20 | EMDR | OTH | PTSS | YES | SINGLE | NONE | UNK |

| Ready et al. (2015) | 109 | TF-CBT | OTH | PTSS | YES | MIXED | >50 | 67 |

| Ribchester et al. (2010) | 11 | EMDR | OTH | PTSD | YES | SINGLE | >50 | 45.5 |

| de Roos et al. (2011) | 26 | EMDR | OTH | PTSS | UNK | SINGLE | <50 | 50 |

| Scheeringa et al. (2011) | 17 | TF-CBT | WAIT LIST | UNK | YES | MIXED | <50 | 33.8 |

| Schottelkorb et al. (2012) | 17 | TF-CBT | OTH | UNK | UNK | SINGLE | UNK | 45.2 |

| Smith et al. (2007) | 12 | TF-CBT | WAIT LIST | PTSD | YES | SINGLE | NONE | 50 |

| Wadaa et al. (2010) | 12 | EMDR | NO TX | PTSD | UNK | SINGLE | NONE | 51.7 |

Note. N = 30. OTH, Other; TAU, Treatment as Usual; NO TX, No Treatment; PTSD, PTSD Diagnosis; PTSS, Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms; UNK, Unknown; YES, Comorbid Diagnoses Present; NO, No Comorbidity; SINGLE, Single Trauma Examined; MIXED, Multiple Traumas Examined; > 50 = > 50% Complex Trauma Present in Sample; < 50 = < 50% Complex Trauma Present in Sample

Measures

Posttraumatic stress symptoms were measured with various instruments (see Appendix Table 6), and each eligible study reported scores from at least one of these instruments. When studies provided more than one measure of trauma-related symptoms, data from only one was used. Likewise, studies using subscales of these measures were coded for the subscale most closely measuring trauma symptoms.

Table 6.

Comprehensive List of Measures from Included Studies

| Adverse Events Checklist (AEC) | |

| Anxiety Disorders Interview Scale for DSM-IV – Child & Parent Version (ADIS-C/P) | |

| Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) | |

| Child Posttraumatic Stress Reaction Index (PTS-RI) | |

| Child PTSD Symptom Scale (CPSS) | |

| Child Reaction Index (CRI) | |

| Child Report of Posttraumatic Symptoms (CROPS) | |

| Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for Children & Adolescents (CAPS-CA) | |

| Impact of Event Scale (IES) | |

| Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R) | |

| Kauffman Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children – Present and Lifetime Version – PTSD section (K-SADS-PL-PTSD) | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL) | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – Abbreviated (PCL-A) | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Symptom Scale for Children (PTSS-C) | |

| Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA) | |

| UCLA PTSD Reaction Index (UPID) |

Coding Procedure

Studies were coded by four clinical psychology graduate students who had been trained in traumatic stress disorders utilizing a standardized and subject-specific coding manual. Study variables included sex, ethnicity, average age, the average time since the trauma (measured in months), location of study, type of trauma, diagnosis, and comorbid diagnosis. Additional variables included publication year, type of treatment, research design, comparison group, and presence of complex trauma. Two researchers coded each article blindly. Thereafter, coding protocols were randomly selected and cross-referenced by two additional researchers, a licensed clinical psychologist and clinical psychologist in postdoctoral training who were both trained in meta-analysis. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion until agreement was reached. Inter-rater reliability was calculated and researchers achieved an overall percent agreement of .80, demonstrating excellent agreement. The final set of data was then entered into the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis program (Version 2.0; Biostat 2005) for analysis.

Data Analysis

Effect sizes were calculated to examine the differences in trauma scores in participants at pre- and post-test intervals to assess the effectiveness of EMDR or TF-CBT. Cohen’s d was calculated using the means, standard deviations, and sample sizes from the post-treatment outcome scores for each group, however, 10 studies did not provide the means and standard deviations scores for each group. For nine of those studies, effect sizes were calculated based on paired groups utilizing sample size and t-value; pre- and post-mean values, sample size, and t-value; or pre- and post-mean, sample size, and p-value. The final study’s effect size was calculated with a correlation r-value and sample size.

Once the effect size was calculated for each study, a Random Effects Model (REM) approach was used, as this model is most appropriate due to the inherent variability across studies. The Cohen’s d value for each study was then transformed into a Hedge’s g value to avoid bias due to variation in sample sizes, and then the Hedge’s g values were transformed back into Cohen’s d values. The Q statistic was utilized to calculate heterogeneity of effect sizes (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). In order to account for the variance found within heterogeneity, moderator variables such as type of treatment, country, trauma type, complex trauma, diagnosis, and comorbidity were calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) Q tests (Borenstein et al. 2009). In addition, I2 was calculated to determine the percentage of variation due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Lipsey and Wilson 2001).

In order to account for possible unpublished data, three publication bias tests were run. First, Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim and fill procedure was utilized to determine the number of studies that would need to be excluded from the point estimate. Second, the Classic fail-safe N was calculated to provide an estimate of how many unpublished studies it would take to raise the p value to .05 (Orwin 1983). Third, the Orwin’s fail-safe N was calculated as a more conservative estimate of how many unpublished studies it would take to nullify the results found (Orwin 1983).

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 1192 children and adolescents participated in the 30 studies included in the meta-analysis (See full summary description in Table 2). Children and adolescents’ mean age in years across studies was 12.22 with four studies that did not report participant age. Many of the participants self-reported suffering from multiple types of traumatic events, including physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; natural disasters; car accidents; and wartime exposure. While approximately nine studies were conducted in the United States, other studies included participants from Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Africa, Sweden, Norway, Holland, Jordan, Iraq, and Iran.

Studies included were published peer-reviewed journal articles that provided community- or school-based interventions with sessions for individual children or parent-child dyads, as well as group interventions. Twenty-one of the studies utilized TF-CBT and nine utilized EMDR. Nineteen studies indicated participants suffered from posttraumatic stress symptoms, whereas participants in eight studies met criteria for a full diagnosis of PTSD, and such information was unknown for three studies. In addition, a majority of studies reported participants suffered from comorbid mental health conditions in addition to PTSS or PTSD (e.g., depression, substance abuse disorders). Nineteen of the included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), ten studies utilized a one-group, pretest-posttest design, and one study utilized a quasi-experimental design.

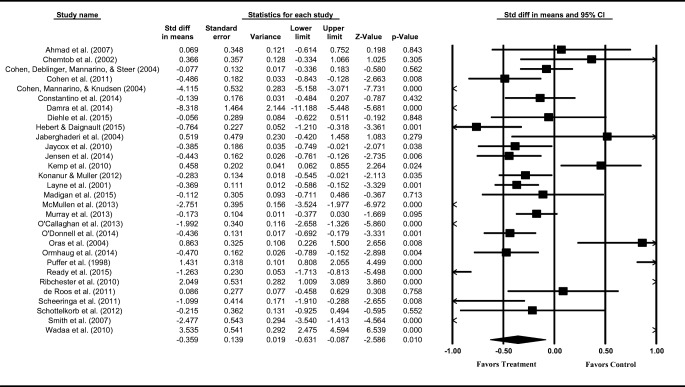

Overall Effect Size and Heterogeneity Analysis

Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d; though, effect sizes were converted to Hedge’s g for all analyses to decrease the overestimation bias of Cohen’s d when utilized with small samples. To further aid in interpretability, all effect sizes were converted back to Cohen’s d after analysis. In using a Random Effects Model (REM), the overall mean effect size across studies was −0.359 (SE = 0.139) indicating a decrease in measured symptoms following treatment. The 95% confidence interval shows a lower limit of −0.631 and an upper limit of −0.087 (see Table 3). The Cohen’s d values across a majority of included studies show that treatment has a significant effect. Despite this significance in the direction of the effect size, the test for heterogeneity revealed significant variation in amount of the effect Q (29) = 333.02; p < .001. Figure 1 shows the effect size data for each study as well as the overall mean. Variance proportion analysis (I2) indicates that approximately 91% of the observed variance appears to be true variation rather than chance. This provides evidence that further analysis is necessary in order to explain this variation.

Table 3.

Total Mean Effect of Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms of Children and Adolescents

| Outcome | k | g | CI95% | Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSS | 30 | −0.359* | −0.631 – −0.87 | 333.021* |

Note. k, Number of studies, g, hedge’s g, CI95%, 95% confidence interval, Q, test of homogeneity

*p < .005

Fig. 1.

Treatment with children and adolescents for PTSS reduction – overall summary effect size results. Note. The graph displays effect size estimates of each study as boxes and their 95% confidence intervals as whiskers. The effect size estimate of the combined result or summary effect size is displayed as a rhombus

Moderator Analyses

In order to explain the true variance between studies, six moderator analyses were conducted to assess the impact of (a) type of treatment, (b) country, (c) type of trauma, (d) complexity of trauma, (e) diagnosis, and (f) comorbidity on effect size (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Homogeneity Statistics

| Homogeneity within all groups | Homogeneity between the groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q w | df | p | Q b | df | p | |

| Treatment of PTSS | ||||||

| Type of Treatment | 235.70 | 28 | .000 | 31.36 | 1 | .000 |

| Country | 332.89 | 28 | .000 | .69 | 1 | .406 |

| Trauma Type | 329.96 | 28 | .000 | .002 | 1 | .960 |

| Complex Trauma | 294.72 | 26 | .000 | 4.94 | 3 | .176 |

| Diagnosis | 318.23 | 28 | .000 | 6.95 | 1 | .008 |

| Comorbidity | 304.89 | 27 | .000 | 13.72 | 2 | .001 |

Note. Qw, test of homogeneity within all studies; Qb, omnibus test of homogeneity between the categories; df, degrees of freedom; p, error probability

Type of Treatment

Type of treatment was grouped into EMDR and TF-CBT. The 21 studies that treated samples with TF-CBT displayed the largest mean effect size of −0.813, (SE = 0.135, p = .000) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −1.077 to −0.549. Whereas the nine studies that employed EMDR had a mean effect size of 0.959 (SE = 0.286, p = .001) and a confidence interval of 0.398 to 1.521. The test for variance between subgroups showed a statistically significant difference, QBetween (1) = 31.36; p < .001.

Country

Country was grouped into either Domestic (i.e., within the Continental United States) or International. Analysis of variance revealed there were no significant differences in the effect sizes of studies from either region, QBetween (1) = 0.692; p = .406. The nine studies conducted in the United States displayed the largest mean effect size of −0.552 (SE = 0.284, p = .052) whereas the 21 studies conducted internationally had a mean effect size of −0.279 (SE = 0.165, p = .090).

Type of Trauma

Type of trauma was grouped into single and mixed. Analysis of variance revealed there were no significant differences in the effect sizes of studies with either single or mixed trauma type, QBetween (1) = 0.002; p = .960. The 23 studies that examined participants who experienced a single type of trauma achieved a significant effect size of −0.369 (SE = 0.168, p = .028); whereas the seven studies examining participants who experienced a multitude of different types of trauma (i.e., mixed) had a mean effect size of −0.355 (SE = 0.228, p = .119) and did not evidence a significant effect.

Complexity of Trauma

Complexity of trauma was analyzed by reviewing samples grouped into those whose majority of the sample represented the presence of complex trauma and those whose minority of the sample represented the presence of complex trauma. Analysis of variance revealed there were no significant differences in the effect sizes of studies with either the majority or minority of complex trauma present within the sample, QBetween (3) = 4.94; p = .176. The 16 studies that represented those with the presence of complex trauma within the majority of the sample achieved a significant effect size of −0.516 (SE = 0.149, p = .001); whereas the seven studies representing those with the presence of complex trauma within the minority of the sample had a mean effect size of −0.713 (SE = 0.415, p = .086) and did not evidence a significant effect. In addition, the six studies that did not include complex trauma within the sample had a mean effect size of 0.524 (SE = 0.490, p = .285) and one study that was coded as unknown evidenced an effect size of −0.215 (SE = 0.362, p = .552).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis was analyzed by grouping studies into those that characterized participants to have a PTSD diagnosis versus those exhibiting sub-clinical PTSS. The 22 studies that treated samples with PTSS exhibited the largest mean effect size of −0.602 (SE = 0.152, p = .000) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −0.900 to −0.305. In addition, eight studies that treated samples with diagnoses of PTSD had a mean effect size of 0.433 (SE = 0.362, p = .232) and a confidence interval of −0.277 to 1.142. The test for variance between subgroups showed a statistically significant difference, QBetween (1) = 6.95; p = .008.

Comorbidity

Comorbidity was analyzed via grouping studies that characterized participants to have comorbid diagnoses versus those who did not. The 18 studies that treated samples with comorbid diagnoses displayed the largest mean effect size of −0.798 (SE = 0.196, p = .000) with a 95% confidence interval ranging from −1.182 to −0.413. The three studies that treated samples without comorbid diagnoses had a mean effect size of 0.281 (SE = 0.367, p = .445) and confidence interval of −0.439 to 1.001. In addition, nine studies in which such data was unknown revealed a mean effect size of 0.172 (SE = 0.214, p = .421). The test for variance between subgroups showed a statistically significant difference, QBetween (2) = 13.72; p = .001).

Publication Bias

A series of publication bias tests were run in order to account for small sample studies with small effects that are potentially underrepresented. Publication bias is problematic in that studies that do not yield significant results are not as likely to be published or included in meta-analyses (Borenstein et al. 2009). The possibility of publication bias was assessed through the funnel plot of effect sizes and two forms of fail-safe N were analyzed. First, asymmetry was evaluated using the Duval and Tweedie’s Trim and Fill procedure and it was determined that no studies needed to be excluded from the point estimate. Next, analysis of the Classic fail-safe N provided an estimate of how many insignificant unpublished studies it would require to raise the p value to .05. Analysis revealed it would take approximately 457 studies to nullify the effect found in this meta-analysis. Furthermore, investigation of the more conservative Orwin’s fail-safe N revealed it would take 60 studies with effect sizes equal to 0.00 to bring the mean effect size to a trivial Cohen’s d of 0.05. As such, these results posit that no substantial evidence of publication bias was evident, indicating the effect sizes reported are robust measures of the treatment effect.

Discussion

Overall, this meta-analysis found clear support for the two leading evidence-based trauma treatments available, EMDR and TF-CBT, as effective methods for reducing PTSS in children and adolescents. When further analyzing variability among the studies, findings indicated that TF-CBT is marginally more effective in reducing PTSS posttreatment than EMDR. In addition, those who reported PTSS but did not meet criteria for a full PTSD diagnosis showed significantly greater reductions in PTSS following treatment than those who were diagnosed with PTSD. Of notable interest, children and adolescents with comorbid diagnoses showed a significantly positive response to treatment as defined by reduction in PTSS when compared to those who did not carry multiple diagnoses.

Results regarding these modalities’ overall effectiveness are supported by several previous meta-analyses (de Arellano et al. 2014; Cary and McMillen 2012; Rodenburg et al. 2009; Rolfsnes and Idsoe 2011; Silverman et al. 2008). These studies found children and adolescents had reduced levels of PTSS following treatment when provided with either EMDR or TF-CBT. There is a dearth of research directly comparing the efficacy of these two modalities in children and adolescents. A search for primary research comparing the efficacy of EMDR and TF-CBT yielded a single study by Diehle et al. (2015). The results of this randomized controlled trial found both treatments to be effective at reducing PTSS in children with only a small nonsignificant difference between the two modalities. The findings of our study are inconsistent with the Diehle et al. (2015) study. Namely, our study made a clear distinction between children and adolescents who received TF-CBT and those who received EMDR, with those receiving TF-CBT evidencing a greater posttreatment reduction in PTSS. Though not a direct comparison of TF-CBT and EMDR, a meta-analysis by Ho and Lee (2012) examining EMDR and exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapy found no difference between these methods in treating PTSD with adults. However, EMDR was found to be more effective than exposure-based CBT in reducing comorbid depression and homework compliance was thought to be a mediating factor (Ho and Lee 2012).

In our study, TF-CBT was found to be marginally superior to EMDR with children and adolescents. While no specific components analyses were performed, we postulate that the core principal of the use of gradual exposure is a significant responsible factor for its effectiveness. More specifically, each component of TF-CBT incorporates gradual exposure to the child’s traumatic experience, and the intensity of the exposure also incrementally increases as both the child and parent systematically engage in the treatment. As exposure is generally considered the gold standard for treatment of anxiety, and the experience of trauma has also been conceptualized as an anxiety disorder prior to the development of the most recent DSM-5, it is logical that gradual exposure would be a significant responsible factor for the treatment of traumatic experiences. We also postulate that the unique components of intensive cognitive and behavioral skill building, homework outside of session, and caregiver components could be responsible factors for its effectiveness. Given that the involvement of caregivers allows for maintenance of skills built during therapy sessions, such a component also provides generalizability of skills to their use outside of therapy. Future research is necessary to investigate components responsible for each modality’s effectiveness with children and adolescents. As a result, this could improve clinicians’ ability to appropriately refer clients for either type of treatment based on individual needs.

Analyses confirmed that children with a diagnosis of PTSD demonstrated a less favorable response than those who did not meet criteria for a full diagnosis. Children experiencing subclinical levels and those with clinical levels of posttraumatic stress have been examined together in previous studies (Jensen et al. 2014; Mannarino et al. 2012). This finding suggests children who meet subclinical levels of PTSD experience greater magnitude of symptom reduction. This is likely related to their baseline symptoms being comparatively less severe than children diagnosed with PTSD. Thus, the present findings provide valuable insight into the importance of early intervention. Intervention at subclinical levels of posttraumatic stress or closely following trauma can decrease the likelihood of children developing PTSD. Further research is warranted to determine the influence of delays between traumatic events and subsequent therapeutic intervention.

Results demonstrated children who presented with comorbid diagnoses experienced significantly greater reductions in PTSS than those with a single diagnosis. Previous research has found reductions in symptoms of comorbid disorders when TF-CBT is utilized (Damra et al. 2014; Diehle et al. 2015). Treatment plans for children with comorbid diagnoses may include an interdisciplinary approach with medication in conjunction with therapeutic intervention. Similarly, children with complex presentations may not only show a greater reduction in PTSS following treatment, but may also develop better coping strategies that can translate across presenting problems demonstrating solid skills acquisition with these forms of treatment.

Studies included in this meta-analysis involved children and adolescents who had experienced a variety of different types of trauma (e.g., fireworks disaster, sexual abuse, motor vehicle accident, and physical abuse). Results showed that type of trauma did not relate to treatment effectiveness. This is consistent with previous findings (Diehle et al. 2015; Wadaa et al. 2010) and suggests these two modalities are effective across various types of traumas.

Analyses also demonstrated there to be no significant treatment effect for children who presented with complex trauma. Complex trauma refers to the exposure to multiple traumatic events, often of an invasive and interpersonal nature, as well as the wide-ranging, long-term impact of this exposure (National Child Traumatic Stress Network 2014). Herman (1992) and Van der Kolk (2005) argued for a distinction to be made between complex PTSD and non-complex PTSD, and discussed the traumatic reactions in the context of compromised caregiving. Numerous studies have investigated the differences in treatment efficacy for complex and non-complex trauma (Connor et al. 2015; Copping et al. 2001; Dozier et al. 2008; Ford et al. 2012; Harvey and Taylor 2010; Kagan 2009; Lowell et al. 2011; Najavits et al. 2006; Spinhoven et al. 2009). Though these studies’ samples included children with clinical features of complex PTSD, treatments did not include EMDR or TF-CBT. In the present study, there was no statistically significant difference in the overall effect size for studies coded as complex versus non-complex trauma. However, the large amount of heterogeneity could account for this unexpected result. There are many factors that potentially increase variability across studies. Depending upon the onset of trauma and time between a subsequent traumatic experience, a child may struggle to cope simply due to limited time to process and heal from the first experience. Additionally, trauma is subjective in nature in that each child responds differently based upon one’s personal history. As such, the nature and extent of the trauma that a child or adolescent has experienced could be an important consideration early in the therapeutic process when offering these modalities of treatment.

The current study revealed no differences in treatment offered based on location of study. Treatment offered within the United States as well as abroad, representing numerous continents, had relatively similar reduction rates of PTSS. These results are also supported by findings in EMDR and TF-CBT effectiveness research, in which children and adolescents responded to treatment similarly across several countries (Ahmad et al. 2007; Hebert and Daignault 2015; Jaberghaderi et al. 2004). Thus, treatment efficacy may not be adversely affected by geographical location.

Clinical Implications

Given that TF-CBT was found to be marginally more effective than EMDR, several implications are important to consider. One important element that is unique to TF-CBT includes the flexibility of this particular treatment model. Clinicians are encouraged to be creative in developing effective means of conveying concepts to children and adolescents of varying ages and comprehension levels. In addition, TF-CBT offers an artistic and play element of the narrative exposure to the experienced trauma, wherein children and adolescents are encouraged to engage in directive play. For example, a trauma narrative for a child might consist of making a comic book about the trauma(s) that occurred, which is then processed with the clinician. Another trauma narrative example might include setting up dolls in a playhouse in an intentional way to represent elements of the trauma. Since children naturally process their experiences through art and play, this element may be a driving force for the relative effectiveness of TF-CBT. Additionally, psychoeducation offered in TF-CBT can instill both safety and body boundary lessons, which may be more applicable to certain types of experienced traumas (e.g., sexual abuse). TF-CBT sessions offered for parents both with and without the child can offer them the opportunity to learn about and to reinforce utilized interventions. Such sessions also assist parents in learning elements of positive reinforcement of appropriate behaviors as well as extinction of inappropriate behaviors to aid in the healing process outside of sessions. Additionally, though parents may be present during EMDR sessions, they are instructed not to intervene (Ahmad and Sundelin-Wahlsten 2008). As such, caregivers of children receiving EMDR likely do not have a level of collaboration and rapport with therapists comparable to conjoint sessions in TF-CBT. These factors could account for the aforementioned differences in effectiveness between these two leading treatments. However, EMDR may be more helpful for those children who struggle with language difficulties, as there are less reading- and writing-based elements than in TF-CBT. Further investigation on the differential effectiveness for different children is warranted.

Limitations

The findings of this meta-analysis are promising; however, there are several limitations that need to be acknowledged. While overall effectiveness was found for both EMDR and TF-CBT, there was high heterogeneity among the studies included in the analysis. The totality of variance could not be explained despite several heterogeneity studies, potentially due to a number of studies not using a comparison group, making it difficult to provide a relative comparison to quantify effectiveness. However, approximately one-third of included studies utilized intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis instead of per-protocol analysis (PPA), meaning that dropouts (if any were noted) were included within the treatment group, potentially underestimating the overall treatment effect. Such an underestimation is difficult to interpret given that dropouts do not fully complete or likely benefit from treatment to the same degree as those who complete treatment. While the included studies did vary considerably with high heterogeneity across treatment-specific and client characteristic analyses, research designs were generally considered strong.

Other methodological limitations should be considered in interpreting the results. There were an unequal number of studies using TF-CBT and studies using EMDR (21 and nine, respectively). It is possible the results are due to one modality being overrepresented in rel1ation to the other. While we have postulated some theories as to the potential reasons for the significant difference found between them (e.g., homework, skill building, caregiver component), there is no current evidence from this study to support and thus points to future research. Additionally, many studies modified the treatment protocols to make them developmentally appropriate for children; however, those modifications were often not specified. Given that a certain amount of variability is inherent in psychological treatment based on variables such as therapist training level and personality, treatment delivery, and other factors, exact replication of conditions is not possible. In order to mitigate this limitation, the use of a Random Effects Model (REM) was most appropriate in offering weighted effect sizes. Still, this study was unable to examine components responsible for the differences between these techniques.

The studies’ analyses generally did not separate children from adolescents, nor separate the differences in effectiveness of treatment for boys and girls or identify the specific diversity within the populations studied. A wide range of emotional, social, and cognitive development occurs over the span of childhood and adolescence. Examining these age ranges together masks these differences and limits the degree to which reduction of PTSS can be attributed to the treatment rather than the child’s developmental stage. While many of the selected studies provided incomplete information regarding the gender and ethnic breakdown of their samples, studies from several countries were included, which provides a preliminary basis for the effectiveness of these treatments with international samples. It is likely that the manualized nature of these interventions makes them adaptable to diverse populations.

Of the studies included, a few contained unclear information or missing data that may have impacted the results. Certain codes had to be estimated based on a range provided or denoted as missing data when the information was not stated. Thus, this may have impacted the overall treatment effect. For example, two articles did not specify the presence of complex trauma within the sample and were included as unknown (missing data) within the analysis. An example of unclear information included that of an article not explicitly stating whether participants were excluded if they had received previous treatment or were taking psychotropic medication; thus, researchers had to make an educated guess from the available data. Inferring codes was only employed when multiple sources of information within the study supported an educated guess; however, there still exists the possibility for human error. The blind coding and inter-rater reliability process helped control for and mitigate this limitation.

Future Directions

While the present study clarified the impact of EMDR and TF-CBT treatments, there are recommendations for future studies on the treatment of posttraumatic symptoms for children and adolescents. As the present study included all categories of trauma in its review (e.g., sexual trauma, accidents, complex trauma, natural disaster, etc.), a recommendation is to focus on one specific type of trauma rather than including all categories. Given that recommendations for treatment may differ based on the type of trauma experienced (e.g., sexual trauma versus complex trauma), limiting analysis to a singular trauma can assist researchers in identifying treatment effectiveness based on trauma type. Research examining potential impacts that children and adolescents may face as a result of lapsed time between the experience of the traumatic event and when treatment is sought warrants attention. As it is generally acknowledged that the best course of action involves intervening as early as possible to treat trauma symptoms, there are currently no guidelines on specific timeframes to intervene nor the most beneficial type of treatment. It is possible that these vulnerable populations might be better served in learning the effects of early intervention if future research can identify trends in lapsed time from experiencing a trauma to when treatment is first sought.

The research base has raised pertinent questions about what aspects of TF-CBT and EMDR are responsible for their beneficial effects. For example, some researchers have concluded that it is not the eye movement component of EMDR that provides the therapeutic benefits (Seidler and Wagner 2006), but rather the exposure to the trauma (Davidson and Parker 2001; Foa and Meadows 1997). This study did not clarify this issue. EMDR’s basic procedure involves bilateral stimulation whereas TF-CBT incorporates intensive cognitive and behavioral skill building, homework outside of session to assist in concretizing concepts, and caregiver components. While it is possible that such components may be responsible factors for TF-CBT’s marginal superiority to EMDR, further investigation is warranted into the change mechanisms of these modalities. Outlining specific treatment procedures allows for replication by others. Future studies that seek to clarify the beneficial components of these treatments would advance the field’s understanding of treatment for posttraumatic symptoms in children and adolescents.

Future researchers are encouraged to gather better data from participant samples regarding any previous treatment they may have received. While it is entirely possible that some children and adolescents may have received some type of treatment for a previous trauma (or for the current identified trauma), such information might make a difference in the results found. It may be worthwhile for future meta-analyses to examine pharmacological effects, comorbid diagnoses, and participants’ trauma histories in more detail. More specifically, it would be helpful to know the effects of adjunctive psychopharmacology treatment with these modalities in comparison to the effectiveness of the modalities alone. Furthermore, the present meta-analysis included studies of participants with and without comorbid diagnoses and who either met full PTSD diagnostic criteria or had subthreshold symptoms. Given that the articles included were comprised of heterogeneous samples, it is difficult to otherwise identify the nature of the comorbidity present without this information further detailed. In addition, many studies did not identify the extent of participants’ trauma histories, and as such, a more extensive clinical history would be of great value. As a result, future researchers are encouraged to examine homogeneous samples detailing psychopharmacology treatment, comorbid diagnoses, and posttraumatic symptoms in order to strengthen future meta-analytic findings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would first like to posthumously thank our professor, advisor, mentor, and co-author, Dr. Siobhan K. O’Toole, for her guidance and tutelage, as well as sharing with us her passion for meta-analysis. The authors would like to thank Jennie L. Bedsworth, LCSW, who serves as a Licensed Clinical Social Worker in the state of Missouri, for her knowledge and expertise in trauma-focused therapies for vulnerable populations that have significantly informed our discussion for this research endeavor. And finally, the authors would like to thank Colt J. Blunt, Psy.D., L.P., for his thoughtful editing of this manuscript.

Appendix

Appendix

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Footnotes

Siobhan K. O’Toole is recognized for her authorship posthumously.

The first author delineates that this article and included views and research findings are the author’s own and are in no way affiliated with Minnesota Department of Human Services, Direct Care and Treatment – Forensic Services.

References

*References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

- Adler-Nevo G, Manassis K. Psychosocial treatment of pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: The neglected field of single-incident trauma. Depression and Anxiety. 2005;22(4):177–189. doi: 10.1002/da.20123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Abdulbaghi, Sundelin-Wahlsten Viveka. Applying EMDR on children with PTSD. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;17(3):127–132. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0646-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Abdulbaghi, Larsson Bo, Sundelin-Wahlsten Viveka. EMDR treatment for children with PTSD: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;61(5):349–354. doi: 10.1080/08039480701643464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biostat . Comprehensive meta-analysis [computer software] [version 2.0] Englewood: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Black PJ, Woodworth M, Tremblay M, Carpenter T. A review of trauma-informed treatment for adolescents. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne. 2012;53(3):192–203. doi: 10.1037/a0028441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins J, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cary CE, McMillen JC. The data behind the dissemination: A systematic review of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for use with children and youth. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(4):748–757. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavett AM, Drewes AA. Play applications and skills components. In: Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E, editors. Trauma-focused CBT for children and adolescents: Treatment applications. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob Claude M., Nakashima Joanne, Carlson John G. Brief treatment for elementary school children with disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A field study. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;58(1):99–112. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway . Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children affected by sexual abuse or trauma. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. A treatment study for sexually abused preschool children: Initial findings. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:42–50. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Interventions for sexually abused children: Initial treatment findings. Child Maltreatment. 1998;3:17–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559598003001002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children and parents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2008;13(4):158–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2008.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Judith A., Deblinger Esther, Mannarino Anthony P., Steer Robert A. A Multisite, Randomized Controlled Trial for Children With Sexual Abuse–Related PTSD Symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN JUDITH A., MANNARINO ANTHONY P., KNUDSEN KRAIG. Treating Childhood Traumatic Grief: A Pilot Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(10):1225–1233. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000135620.15522.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Iyengar, S. (2011). Community treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder for children exposed to intimate partner violence: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(1), 16–21. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.247. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Connor DF, Ford JD, Arnsten AT, Greene CA. An update on posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clinical Pediatrics. 2015;54(6):517–528. doi: 10.1177/0009922814540793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copping VE, Warling DL, Benner DG, Woodside DW. A child trauma treatment pilot study. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2001;10(4):467–475. doi: 10.1023/A:1016761424595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino Giuseppe, Primavera Louis H., Malgady Robert G., Costantino Erminia. Culturally Oriented Trauma Treatments for Latino Children Post 9/11. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma. 2014;7(4):247–255. doi: 10.1007/s40653-014-0031-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damra Jalal Kayed M., Nassar Yahia H., Ghabri Thaer Mohammd F. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy: Cultural adaptations for application in Jordanian culture. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2014;27(3):308–323. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2014.918534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PR, Parker KH. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(2):305–316. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Arellano Michael A. Ramirez, Lyman D. Russell, Jobe-Shields Lisa, George Preethy, Dougherty Richard H., Daniels Allen S., Ghose Sushmita Shoma, Huang Larke, Delphin-Rittmon Miriam E. Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Children and Adolescents: Assessing the Evidence. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(5):591–602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roos Carlijn, Greenwald Ricky, den Hollander-Gijsman Margien, Noorthoorn Eric, van Buuren Stef, de Jongh Ad. A randomised comparison of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) in disaster-exposed children. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2011;2(1):5694. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.5694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Runyon MK, Steer RA. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(1):67–75. doi: 10.1002/da.20744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehle Julia, Opmeer Brent C., Boer Frits, Mannarino Anthony P., Lindauer Ramón J. L. Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: what works in children with posttraumatic stress symptoms? A randomized controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;24(2):227–236. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Peloso E, Lewis E, Laurenceau J, Levine S. Effects of an attachment-based intervention of the cortisol production of infants and toddlers in foster care. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(3):845–859. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Meadows E. Psychosocial treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A critical review. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48(1):449–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen JA. Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Foley T, Spates CR. Eye movement desensitization of public-speaking anxiety: A partial dismantling. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1995;26(4):321–329. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(95)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Steinberg K, Hawke J, Levine J, Zhang W. Evaluation of trauma affect regulation—Guide for education and therapy (TARGET) with traumatized girls involved in delinquency. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41(1):27–37. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.632343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald R. Eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in child and adolescent psychotherapy. New York: Jason Aronson; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Greyber LR, Dulmus CN, Cristalli ME. Eye movement desensitization reprocessing, posttraumatic stress disorder, and trauma: A review of randomized controlled trials with children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2012;29(5):409–425. doi: 10.1007/s10560-012-0266-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey ST, Taylor JE. A meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapy with sexually abused children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(5):517–535. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert M., Daignault I.V. Challenges in treatment of sexually abused preschoolers: A pilot study of TF-CBT in Quebec. Sexologies. 2015;24(1):e21–e27. doi: 10.1016/j.sexol.2014.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helland, M. J., & Mathiesen, K. S. (2009). 13–15 aringer fra vanlige familier i Norge: Hverdagsliv og psykisk helse [13–15 year-olds from regular families in Norway: Everyday life and mental health]. Retrieved from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health website: http://www.fhi.no/dokumenter/d2d94780d4.pdf

- Herman JL. Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence—From domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ho MK, Lee CW. Cognitive behaviour therapy versus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for post-traumatic disorder—Is it all in the homework then? European Review of Applied Psychology / Revue Européenne De Psychologie Appliquée. 2012;62(4):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2012.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howe D. Child abuse and neglect: Attachment, development, and intervention. New York: Palgrave; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jaberghaderi Nasrin, Greenwald Ricky, Rubin Allen, Zand Shahin Oliaee, Dolatabadi Shiva. A comparison of CBT and EMDR for sexually-abused Iranian girls. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2004;11(5):358–368. doi: 10.1002/cpp.395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Jaycox. L. H., Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Walker, D. W., Langley, A. K., Gegenheimer, K. L., Scott M. Schonlau, M. (2010). Children's mental health care following hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(2), 223–231. 10.1002/jts.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jensen Tine K., Holt Tonje, Ormhaug Silje M., Egeland Karina, Granly Lene, Hoaas Live C., Hukkelberg Silje S., Indregard Tore, Stormyren Shirley D., Wentzel-Larsen Tore. A Randomized Effectiveness Study Comparing Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy With Therapy as Usual for Youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;43(3):356–369. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan R. Transforming troubled children into tomorrow's heroes. In: Brom D, Pat-Horenczyk R, Ford JD, Brom D, Pat-Horenczyk R, Ford JD, editors. Treating traumatized children: Risk, resilience and recovery. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. pp. 255–268. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp Michael, Drummond Peter, McDermott Brett. A wait-list controlled pilot study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for children with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms from motor vehicle accidents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;15(1):5–25. doi: 10.1177/1359104509339086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Konanur, S., & Muller, R. (2012). A community-based study of the effectiveness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral with trauma-exposed school-aged children in Toronto, Canada. International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) 28th Annual Meeting: Innovations to Expand Services and Tailor Traumatic Stress Treatments, November 1–3, 2012, Los Angeles, CA [Abstracts]. 10.1037/e533652013-128.

- Kowalik J, Weller J, Venter J, Drachman D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2011;42(3):405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne Christopher M., Pynoos Robert S., Saltzman William R., Arslanagić Berina, Black Mary, Savjak Nadezda, Popović Tatjana, Duraković Elvira, Mušić Mirjana, Ćampara Nihada, Djapo Nermin, Houston Ryan. Trauma/grief-focused group psychotherapy: School-based postwar intervention with traumatized Bosnian adolescents. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2001;5(4):277–290. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.5.4.277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz AS, Hollenbaugh KM. Meta-analysis of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for treating PTSD and co-occurring depression among children and adolescents. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation. 2015;6(1):18–32. doi: 10.1177/2150137815573790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Little SG, Akin-Little A. Trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy. In: Akin-Little A, Little SG, Bray MA, Kehle TJ, editors. Behavioral interventions in schools: Evidence-based positive strategies. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JM, Kleinknecht RA, Tolin DF, Barrett RH. The empirical status of the clinical application of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1995;26(4):285–302. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JM, Tolin DF, Lilienfeld SO. Efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Implications for behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29(1):123–156. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(98)80035-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett J. Small wonders: Healing childhood trauma with EMDR. New York: The Free Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lowell DI, Carter AS, Godoy L, Paulicin B, Briggs-Gowan MJ. A randomized controlled trial of child FIRST: A comprehensive home-based intervention translating research into early childhood practice. Child Development. 2011;82(1):193–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan Sheri, Vaillancourt Kyla, McKibbon Amanda, Benoit Diane. Trauma and traumatic loss in pregnant adolescents: the impact of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy on maternal unresolved states of mind and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Attachment & Human Development. 2015;17(2):175–198. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2015.1006386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannarino AP, Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Runyon MK, Steer RA. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children: Sustained impact of treatment 6 and 12 months later. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17(3):231–241. doi: 10.1177/1077559512451787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen John, O'Callaghan Paul, Shannon Ciaran, Black Alastair, Eakin John. Group trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy with former child soldiers and other war-affected boys in the DR Congo: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54(11):1231–1241. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray Laura K., Familiar Itziar, Skavenski Stephanie, Jere Elizabeth, Cohen Judy, Imasiku Mwiya, Mayeya John, Bass Judith K., Bolton Paul. An evaluation of trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children in Zambia. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(12):1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Gallop RJ, Weiss RD. Seeking safety therapy for adolescent girls with PTSD and substance use disorder: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2006;33(4):453–463. doi: 10.1007/s11414-006-9034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network . Complex trauma: Facts for service providers working with homeless youth and young adults. Los Angeles: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan Paul, McMullen John, Shannon Ciarán, Rafferty Harry, Black Alastair. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Sexually Exploited, War-Affected Congolese Girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(4):359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell Karen, Dorsey Shannon, Gong Wenfeng, Ostermann Jan, Whetten Rachel, Cohen Judith A., Itemba Dafrosa, Manongi Rachel, Whetten Kathryn. Treating Maladaptive Grief and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Orphaned Children in Tanzania: Group-Based Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2014;27(6):664–671. doi: 10.1002/jts.21970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oras Reet, Ezpeleta Susana Cancela de, Ahmad Abdulbaghi. Treatment of traumatized refugee children with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in a psychodynamic context. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;58(3):199–203. doi: 10.1080/08039480410006232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormhaug Silje M., Jensen Tine K., Wentzel-Larsen Tore, Shirk Stephen R. The therapeutic alliance in treatment of traumatized youths: Relation to outcome in a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(1):52–64. doi: 10.1037/a0033884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwin RG. A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1983;8:157–159. doi: 10.3102/10769986008002157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- *Puffer, M. K., Greenwald, R., & Elrod, D. E. (1998). A single session EMDR study with twenty traumatized children and adolescents. Traumatology, 3(2). 10.1037/h0101053.

- Puttre JJ. A meta-analytic review of the treatment outcome literature for traumatized children and adolescents. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2011;72:2445. [Google Scholar]

- Ready C. Beth, Hayes Adele M., Yasinski Carly W., Webb Charles, Gallop Robert, Deblinger Esther, Laurenceau Jean-Philippe. Overgeneralized Beliefs, Accommodation, and Treatment Outcome in Youth Receiving Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Childhood Trauma. Behavior Therapy. 2015;46(5):671–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribchester Tracy, Yule William, Duncan Adam. EMDR for Childhood PTSD After Road Traffic Accidents: Attentional, Memory, and Attributional Processes. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research. 2010;4(4):138–147. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.4.4.138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg R, Benjamin A, de Roos C, Meijer AM, Stams GJ. Efficacy of EMDR in children: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(7):599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfsnes ES, Idsoe T. School-based intervention programs for PTSD symptoms: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24(2):155–165. doi: 10.1002/jts.20622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson A, Carpenter R. Eye movement desensitization versus image confrontation: A single-session crossover study of 58 phobic subjects. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1992;23(4):269–275. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(92)90049-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa Michael S., Weems Carl F., Cohen Judith A., Amaya-Jackson Lisa, Guthrie Donald. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;52(8):853–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottelkorb April A., Doumas Diana M., Garcia Rhyan. Treatment for childhood refugee trauma: A randomized, controlled trial. International Journal of Play Therapy. 2012;21(2):57–73. doi: 10.1037/a0027430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SEIDLER GUENTER H., WAGNER FRANK E. Comparing the efficacy of EMDR and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of PTSD: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(11):1515. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro F. Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1989;2(2):199–223. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490020207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro F. Eye movement desensitization: A new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1989;20(3):211–217. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(89)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro F. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro F. EMDR, adaptive information processing, and case conceptualization. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research. 2007;1(2):68–87. doi: 10.1891/1933-3196.1.2.68. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Ortiz CD, Viswesvaran C, Burns BJ, Kolko DJ, Putnam FW, Amaya-Jackson L. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):156–183. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH PATRICK, YULE WILLIAM, PERRIN SEAN, TRANAH TROY, DALGLEISH TIM, CLARK DAVID M. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for PTSD in Children and Adolescents: A Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(8):1051–1061. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318067e288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Slee N, Garnefski N, Arensman E. Childhood sexual abuse differentially predicts outcome of cognitive-behavioral therapy for deliberate self-harm. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2009;197(6):455–457. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a620c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker RH, Wilson SA. Through the eyes of a child: EMDR with children. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk BA. Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:401–408. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20050501-06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wadaa Najla N., Zaharim Norzarina Mohd, Alqashan Humoud F. The Use of EMDR in Treatment of Traumatized Iraqi Children. Digest of Middle East Studies. 2010;19(1):26–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1949-3606.2010.00003.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner DA, Schneider A, Lyons JS. Evidence-based treatments for trauma among culturally diverse foster care youth: Treatment retention and outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31(11):1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2013). Guidelines for the management of conditions specifically related to stress. Geneva: WHO. [PubMed]