Abstract

The current study investigated relationships between different experiences of child maltreatment (CM) and disordered eating (DE) in a large population-based sample of Danish young adults. Participants completed a structured interview comprising socio-demographic, psychological and physical domains. Questions regarding CM, DE, PTSD symptoms and self-esteem were analyzed using chi-square-tests, ANOVAs, hierarchical regression, and multiple mediation analyses. Participants with a history of CM experienced higher levels of DE than non-abused individuals. PTSD symptoms and self-esteem appeared to differentially mediate the relationship between three classes of CM and DE. Whereas the relation between emotional and sexual abuse with DE was partially mediated via participants’ level of PTSD symptoms and self-esteem with emotional abuse having a stronger impact on self-esteem and sexual abuse more strongly influencing PTSD symptoms, the relation between polyvictimization and DE was fully mediated by PTSD and self-esteem, mainly due to the indirect effect via PTSD.

Keywords: Child maltreatment, Emotional abuse, Sexual abuse, Polyvictimization, Disordered eating, PTSD, Self-esteem

Experiences of child maltreatment (CM), such as physical, sexual or emotional abuse and neglect, increase risk of a variety of health problems and psychological difficulties in adulthood (Kessler et al. 2010). One class of mental disorders that has been mentioned in association with CM is eating disorders (EDs) (Afifi et al. 2017; Becker and Grilo 2011; Groleau et al. 2012; Pignatelli et al. 2017; Smolak and Murnen 2002). EDs are defined as a “persistent disturbance of eating or eating-related behavior” (American Psychiatric Association 2013) that negatively affects physical health and psychosocial functioning and is associated with high levels of mortality (Arcelus et al. 2011). While only a small percentage of the general population qualifies for a clinical ED diagnosis (Javaras and Hudson 2017), considerably higher numbers of individuals suffer from problems regarding eating, weight or shape without fulfilling diagnostic criteria for an ED (Jacobi et al. 2011; Pike and Striegel-Moore 1997). Disordered eating (DE) describes a variety of non-normative eating-related behaviors and attitudes that by themselves do not necessarily warrant a specific diagnosis (Breland et al. 2017; Tanofsky-Kraff and Yanovski 2004), such as a disturbed body perception and evaluation, unhealthy eating habits and compensatory weight control behaviors (Waaddegaard et al. 2003).

Disturbed eating habits include, for example, emotional eating, which means to comfort oneself with food to downregulate emotional stress and negative affect (Sultson et al. 2017). It is closely linked to binge eating which frequently occurs in response to negative affective states and elicits additional negative affect due to its accompanying feelings of shame, guilt, and self-disgust (Pike and Striegel-Moore 1997). During an episode of binge eating the individual eats an amount of food that is larger than what most people would eat under similar circumstances in a certain period of time, accompanied by a sense of lack of control over eating (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

In contrast, restricted eating means the intentional and sustained restriction of caloric intake in order to maintain or lose weight for instance by a restricted diet, meal skipping, or fasting (Ogden 2010). A more extreme method of weight control behaviors are so-called purging behaviors. These describe a range of behaviors forcefully expelling food from the body in order to control body weight and shape (e.g. via self-induced vomiting or medication misuse) (Haedt-Matt 2017). The co-occurrence of binge eating and purging behaviors is characteristic of the ED bulimia nervosa and therefore referred to as bulimic eating psychopathology. Although DE symptoms differ from those of clinical EDs in frequency and/or severity (Pike and Striegel-Moore 1997), they adversely affect psychological and physical health and increase the risk of ED development (Dakanalis et al. 2016a; Dakanalis et al. 2016b; Taylor 2017; Waaddegaard et al. 2003).

There are many studies reporting an association between specific forms of CM and specific DE symptoms in adulthood, although comparing different studies, results are inconsistent. Child sexual abuse (CSA) has been associated with binge eating (Armour et al. 2016; Sachs-Ericsson et al. 2012), dieting and purging (Johnson et al. 2002), body dissatisfaction in men (Brooke and Mussap 2012), and food addiction/emotional eating (Mason et al. 2013), as well as eating, weight, and shape concerns in women (Wonderlich et al. 2001). However, CSA was not independently related to restricted eating, binge eating, and purging (Smyth et al. 2008), bulimic eating psychopathology and body dissatisfaction (Kent et al. 1999), meal skipping and a sense of loss of control (Fuemmeler et al. 2009), and various other DE symptoms (Fischer et al. 2010) in other studies. Regarding physical abuse (CPA), associations have been found with binge eating (Armour et al. 2016; Sachs-Ericsson et al. 2012), as well as restricted eating and purging (Smyth et al. 2008), problematic eating behaviors (Fuemmeler et al. 2009), and food addiction/emotional eating in women (Mason et al. 2013). However, there are also studies which could not find a unique association between CPA and DE (Brooke and Mussap 2012; Fischer et al. 2010; Kent et al. 1999). Emotional abuse (CEA) has been shown to be associated with binge eating (Hymowitz et al. 2017), and drive for thinness, bulimic behaviors, body dissatisfaction, and dieting (Hund and Espelage 2006) and appeared to be the only predictor contributing independently to DE after controlling for other types of CM in two studies (Fischer et al. 2010; Kent et al. 1999). Neglect has rarely been studied in association with nonclinical eating psychopathology but appeared to be related to gender-atypical drive for thinness in men and drive for muscularity in women (Brooke and Mussap 2012), dieting and purging (Johnson et al. 2002).

The results of these studies are difficult to compare, since their respective definitions of CM and DE vary considerably. Most studies have focused on single types of CM, without taking into account that CM is rather a multidimensional phenomenon with certain types of CM rarely occurring alone (Armour et al. 2014; Pears et al. 2008). Separating between typically co-occurring forms of CM may distort the results regarding their unique impact on the individual’s eating behaviors and attitudes (Armour et al. 2014). There are only a few studies comparing more than two different types of abuse and neglect in association with DE (Brooke and Mussap 2012; Fischer et al. 2010; Fuemmeler et al. 2009; Hasselle et al. 2017; Johnson et al. 2002; Kent et al. 1999), but most of them did not consider potential cumulative effects for individuals who were exposed to multiple types of CM. The experience of child polyvictimization (CPV) is generally associated with more severe psychological consequences than single abusive events (Cloitre et al. 2009; Gilbert et al. 2009; Steine et al. 2017) and results of a study by Hasselle et al. (2017) indicated a positive association between the number of childhood victimization experiences and DE. Furthermore, Mason et al. (2013) found women with a history of combined CPA and CSA at greater risk of emotional eating than women who experienced only one of these CM types.

A few recent studies suggest a complex relationship between CM and DE, that is at least partially mediated by other factors such as affective instability (Groleau et al. 2012), alexithymia and general distress (Hund and Espelage 2006), anger (Feinson and Hornik-Lurie 2016), depression (Kong and Bernstein 2009; Mazzeo and Espelage 2002), anxiety and dissociation (Kent et al. 1999), attachment insecurity (Tasca et al. 2013), or emotion dysregulation (Burns et al. 2012; Mills et al. 2015; Moulton et al. 2015).

PTSD symptoms and self-esteem are factors closely linked to both CM and DE but have never been studied simultaneously as mediators of this relationship. PTSD is one of the most frequent consequences of CM experiences of all kinds (Gal and Basford 2015; Gilbert et al. 2009; Sullivan et al. 2006; Vranceanu et al. 2007) and appears to be highly prevalent in individuals with eating psychopathology (Armour et al. 2016; Hirth et al. 2011; Mitchell et al. 2012; Tagay et al. 2014), especially when these individuals have a history of CM (Brewerton 2007; Isomaa et al. 2015; Tagay et al. 2010). To date only one study has specifically investigated a mediational effect of PTSD in the relationship between CM (more precisely CSA) and DE in adulthood (Holzer et al. 2008). However, a person with a history of CM may develop DE as a maladaptive affect regulation strategy to reduce trauma-related negative affect and tension, avoid distressing memories, and decrease hyperarousal as they are present in PTSD symptoms (Hirth et al. 2011; Holzer et al. 2008; Hund and Espelage 2006).

It is presumable, that a person’s appraisal of their own worth is adversely affected by abuse experiences, particularly in childhood while the individual’s self-esteem is still developing and vulnerable to external threats (Bolger et al. 1998; Kent and Waller 2000), which is why individuals with a history of CM typically indicate lower self-esteem than non-abused individuals (Becker and Grilo 2011; Carter et al. 2006). By assuming that controlling body weight or shape may improve one’s self-worth, DE may function as a maladaptive way of coping with a poor self-esteem (Starrs et al. 2017). Low self-esteem has been found to be associated with DE (Dakanalis et al. 2016a; Dakanalis et al. 2016b; Sanlier et al. 2017), and one study reported a mediational role of negative self-perception in the relationship between CEA and DE (Hymowitz et al. 2017).

The existing literature on CM and eating psychopathology is mostly limited by focusing on a single type of CM and a specific DE behavior or clinical ED diagnosis. It is further limited by using unrepresentative clinical or exclusively female samples and disregarding potential confounding factors that may influence the complex relationship between CM and eating problems (Afifi et al. 2017). The aim of the current study is to examine the relationships between different experiences of CM and DE in a large population-based sample of Danish young adults. Furthermore, it will examine the role of self-esteem and PTSD-symptoms as mediators of these relationships. We hypothesize that three classes of CM (CEA, CSA and CPV), that have been previously identified as latent classes of abuse experiences in the present study sample (Armour et al. 2014), are associated with a higher level of DE than the nonabused class, but that they are also differentially related to DE, depending on the particular abuse type. In addition, we hypothesize that the relation between each CM class and DE is at least partially mediated via PTSD symptoms and self-esteem.

Methods

Procedure

The current cross-sectional study is based on data from a stratified random probability survey conducted in Denmark between 2008 and 2009. 4718 participants were randomly selected from the total birth cohort of Denmark in 1984 by Statistic Denmark. Children who had been in child protection were over-sampled by a ratio of 1:2 of “child protection cases” versus “non-child protection cases”. A child protection case was defined according to files of local social workers as a case where the well-being and development of the child was in question, therefore; the council had provided support for the child and its family or placed the child with a foster family. All participants were informed about the nature, purpose, content and procedure of the study.

Participants who refused participation, who were arrested, had learning difficulties or had moved out of the country were excluded. Structured interviews were conducted by trained interviewers at participants’ homes (approximately one third) or via telephone (approximately two thirds of interviews) with an average duration of 43 min. Due to the sensitive nature of some questions, participants interviewed at home could enter their answers to these questions directly into a laptop while the interviewer was unaware of their responses. Participation in the study was completely voluntary and post-interview psychological help was offered via a telephone help-line. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Participants

A total of 2980 interviews (out of 4718) were successfully conducted, resulting in a response rate of 63%. The most common reasons for non-participation were refusal to participate (21%), being unreachable (13%), illness or disability (2%). Eight-hundred fifty-two interviews were conducted with individuals who had been previously identified as child protection cases. All participants were 24 years old at the time of study participation. Of the final sample 1579 participants (53.0%) were male, 2265 (76.0%) had completed or were in vocational or higher education, 2758 (92.6%) owned or rented their own accommodations, and 1361 (45.7%) were married or cohabited with a partner.

Measures

The interview contained a series of questions relating to several socio-demographic, psychological and physical domains with a pre-coded response format and additional opportunity for participants to elaborate their answers, if needed.

Child Maltreatment

Participants were asked if they had experienced 24 different described incidences of maltreatment during childhood relating to CPA, CSA, CEA, and neglect. The items contained examples for each maltreatment experience, thereby trying to minimize flaws by subjective interpretations of participants whether their childhood experiences are a matter of maltreatment or not. For a detailed description of the items, see Christoffersen et al. (2013).

Participants’ responses to these dichotomous abuse questions resulted in the CM classification, which was based on a latent class analysis (LCA) by Armour et al. (2014). LCA is an exploratory method to identify homogeneous subgroups among subjects in a sample that account for differences in observed response patterns among a number of categorical items – in this case the 24 maltreatment incidences. The LCA examined if distinct groups/classes of individuals could be identified in the present sample of young adults who experienced similar patterns of abuse and neglect. Four latent classes of CM experiences were identified. Individuals with the lowest probability of endorsement across all CM items were categorized as non-abused (non-abused class). Participants who had high probabilities of affirmative responses on CEA items and slight probabilities to affirm CPA and neglect items were classified as emotionally abused (CEA class). Some individuals differed only slightly from the non-abused class on CPA, CEA, and neglect items, but had the highest probabilities of affirming CSA items, thus categorized as sexually abused (CSA class). Participants with the highest probabilities of endorsing CPA, CEA, and neglect items and the second highest probabilities of endorsing CSA items were termed polyvictimized (CPV class) (Armour et al. 2014).

Disordered Eating

Disordered eating was measured using eight items, six of which were taken from the Risk Behaviour for Eating Disorders – 8 Items questionnaire (RiBED-8; Waaddegaard et al. 2003), a screening instrument examining core symptoms of DE. The RiBED-8 was validated with a representative sample of 2094 Danish adolescents aged 14–21 and showed good psychometric properties (Waaddegaard et al. 2003). The other two items referred to special dieting behaviors such as use of slimming pills and starvation to indicate more serious DE behavior. All items focused on the individual’s emotional and cognitive reaction to weight gain, dieting strategies, and risk behavior for EDs and participants had to answer them on a four-point Likert-type scale with answers ranging from 1 (very often) to 4 (never). For a better comparability with the response format of the original RiBED-8 scale with answers ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (very often) and thereby better interpretability of the results, items in this study were recoded. Afterwards a sum score was calculated for each individual by counting the number of items that were answered with “often” and “very often”, with higher scores reflecting a higher level of DE. For one item (“I throw up to get rid of food that I have eaten.”) also the answer “rarely” was regarded as the critical cut-off score according to Waaddegaard et al. (2003). Just as in their study, participants scoring on at least three items above the critical cut-off were classified as DE risk-group, being considered at high risk for developing an ED. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale used in the current sample was .72.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptoms

PTSD symptoms were measured using the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD; Prins et al. 2003) with four dichotomous items representing core symptoms of PTSD: Re-experiencing, numbing, avoidance and hyperarousal. Answers were rated in a dichotomous (“yes” versus “no”) format. To determine an individual’s level of PTSD-symptoms, a sum score was calculated of affirmed items with higher scores reflecting more PTSD symptoms. Corresponding to recommendations of Prins et al. (2003), participants with a score ≥3 were classified to be at high risk for PTSD. The PC-PTSD has turned out to be a valid indicator for PTSD in primary care settings with comparable psychometric properties and operating characteristics to other PTSD questionnaires (Prins et al. 2003). Cronbach’s alpha for the scale in the current sample was .70.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg 1965), an established and validated measure to assess global self-esteem (Robins et al. 2001). Its ten items represent statements concerning feelings of worth, self-satisfaction, self-respect and so forth (e.g. “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.”). Participants had to indicate on a four-point Likert-type scale how much they agree with each statement, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). After reverse-scoring the negatively worded items, a total score was calculated by summing up participants responses with higher scores reflecting higher self-esteem. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale in the current study was .81.

Demographic Variables

Participants were further asked via a dichotomous item, whether they were male or female. They could indicate their current living accommodation by choosing one of seven options (e.g. “rented house/apartment”, “living with parents” etc.) including an “other”-option, their completed school education by choosing one of eight options (e.g. “tenth class”, “I am still in the process of school education”) including an “other”-option and could indicate whether they never started, completed, interrupted, or still were in vocational or higher education.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 25. Chi-square analyses and ANOVAs were used to examine if the four CM classes were significantly associated with gender, DE, PTSD symptoms and self-esteem. Due to heterogeneity of variances in the present data, ANOVAs were performed using Welch’s method and post-hoc tests via the Games-Howell method, that both are designed to account for violations of variance homogeneity (Lix et al. 1996). A hierarchical regression analysis was performed to assess the impact of gender, CM classes, PTSD, and self-esteem on DE. Chi-square-, t- and F-estimates as well as standardized ß-coefficients were regarded as statistically significant if p < .05.

For testing the hypothesis of associations between the different predictor variables, multiple mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS procedure (Hayes 2013). In the past mediational hypotheses were frequently tested in psychological research by the method developed by Baron and Kenny (1986), but this method suffers from several limitations and cannot be used for testing multiple mediation. In the current study we wanted to examine a multiple mediator model that accounts for mediational effects in the relationship between different experiences of CM and DE via PTSD symptoms and self-esteem, as well as for a possible serial order of these mediators. Separate mediation analyses were conducted for all three abuse classes (CEA, CSA, and CPV) as predictors. Since gender was significantly related to all other variables, it was used as a covariate in mediation analyses.

Each analysis estimated the total effect (c) of CM class on DE, the direct effect (c’), meaning the effect of CM class on DE adjusted for the mediators and three indirect effects (c-c’) as the effect of CM class on DE via the mediators: PTSD, self-esteem and the two of them as serial mediators in a multiple mediated relationship. Model coefficients are reported in unstandardized form as recommended by Hayes (2013). Thus, regression weights of the direct effect c’ can be interpreted as the estimated difference in DE between a person belonging to the particular CM class and a person who belongs to one of the other classes. All other regression weights (on PTSD symptoms and self-esteem) should be interpreted as the estimated change in the respective dependent variable that comes along with a change of one unit in the respective independent variable. The strength of mediation is displayed as the difference in the estimated paths c and c’. Bootstrapping was performed with 5000 bootstrap draws, and 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effect were estimated using the bias-corrected method. The specified indirect effects were regarded as significantly different from zero, if zero was outside the confidence interval.

Results

A total of 614 participants (20.6%) were classified into one of the abuse classes with the vast majority of them (n = 376, 12.6%) belonging to the CEA class. Fewer individuals belonged to the CSA class (n = 87, 2.9%) and the CPV class (n = 151, 5.1%), compared to 2366 individuals (79.4%) who were classified as non-abused. Two-hundred thirty-three participants (7.8%) reported three or more PTSD symptoms in the PC-PTSD. Two hundred sixty-six individuals (8.9%) scored above the critical cut-off for DE and were classified as DE risk-group.

Table 1 shows the distribution of participants from different CM classes to gender, DE and PTSD risk-group, as well as means and standard deviations of continuous variables for the total sample and each CM class.

Table 1.

Distribution of participants from the total sample and different child maltreatment classes to gender, disordered eating risk-group, PTSD risk-group, and means and standard deviations for each child maltreatment class on disordered eating, PTSD symptoms, and self-esteem

| Child Maltreatment | Gender | Disordered eating | PTSD symptoms | Self-esteem | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Risk-Group | M | SD | Risk-Group | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Emotional Abuse (n = 376) | 46.5% | 53.5% | 13.8% | 1.18 | (1.24) | 15.7% | 1.07 | (1.23) | 30.81 | (4.72) |

| Sexual Abuse (n = 87) | 89.5% | 10.5% | 26.7% | 1.70 | (1.82) | 32.9% | 1.75 | (1.38) | 30.11 | (4.94) |

| Polyvictimization (n = 151) | 52.3% | 47.7% | 17.9% | 1.32 | (1.59) | 31.0% | 1.77 | (1.40) | 30.28 | (4.95) |

| Nonabused (n = 2366) | 45.2% | 54.8% | 7.0% | 0.77 | (1.04) | 4.4% | 0.40 | (0.85) | 32.98 | (3.86) |

| 47.0% | 53.0% | 8.9% | 0.88 | (1.15) | 7.8% | 0.59 | (1.04) | 32.51 | (4.17) | |

Percentages refer to the number of participants of each child maltreatment class

Chi-square tests revealed just one statistically significant difference in gender between CM classes with 89.5% of the CSA class being female, χ2(3) = 67.23, p < .001. There was a significant association between CM class and if participants belonged to the DE risk-group (χ2(3) = 69.13, p < .01). About 26.7% of the CSA class scored above the cut-off, reporting multiple unhealthy eating behaviors and concerns. Percentages among emotionally abused and polyvictimized individuals were lower (13.8 and 17.9% respectively) but still higher than of the non-abused class (7.0%). Treating participants’ DE scores as a continuous variable revealed significant differences between CM classes (Welch’s F(3, 247) = 22.92, p < .01). Post-hoc tests revealed significant differences between the non-abused class and all three abuse classes: CSA (MD = −0.93, SE = .20, p < .01), CPV (MD = −.55, SE = .13, p < .01), and CEA (MD = −0.41, SE = .07, p < .01). No significant differences appeared between the three abuse classes.

Regarding PTSD symptom level, there was a significant difference between CM classes (χ2(3) = 248.55, p < .01). As expected, a strikingly smaller percentage of the non-abused class indicated three or more PTSD symptoms compared to the three abuse classes. The largest portions of individuals suffering from high levels of PTSD symptoms, were found in CPV and CSA classes. CM classes also differed significantly in their continuous PTSD scores, Welch’s F(3, 240) = 97.57, p < .01, with significant differences between the non-abused class and all abuse classes: CSA (MD = −1.35, SE = .15, p < .01), CPV (MD = −1.36, SE = .12, p < .01), and CEA (MD = −0.67, SE = .07, p < .01). Furthermore, the CEA class differed significantly from the CSA (MD = −0.68, SE = .16, p < .01) and CPV class (MD = −0.69, SE = .13, p < .01).

In terms of self-esteem, significant differences appeared between CM classes (Welch’s F(3, 244) = 41.14, p < .01). Individuals of the non-abused class had a significantly higher self-esteem than those of all abuse classes: CSA (MD = 2.87, SE = 0.54, p < .001), CPV (MD = 2.70, SE = 0.42, p < .01), and CEA (MD = 2.17, SE = 0.27, p < .001) with polyvictimized and sexually abused individuals reporting the lowest self-esteem.

Significant gender differences were found in the distribution of men and women among CM classes (χ2(3) = 67.23, p < .01), DE risk- versus non-risk-group (χ2(1) = 102.82, p < .01) and PTSD risk- versus non-risk-group (χ2(1) = 19.60, p < .01), as well as on participants’ continuous DE (Welch’s F(1, 2377) = 210.12, p < .01) and PTSD scores (Welch’s F(1, 2377) = 210.12, p < .01) and self-esteem (Welch’s F(1, 2735) = 43.72, p < .01) with women reporting lower self-esteem, but higher levels of DE and PTSD symptoms than men.

Regression Analysis

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to assess the impact of gender, CM class, PTSD, and self-esteem on respondents’ level of DE. Four different models were compared to each other. With any predictor added to the model, the explained variance of DE increased significantly (p < .01), with the overall model including all predictors explaining 14.6%. We also compared this model to a model, in which participants’ belonging to any of the three abuse classes (compared to being non-abused) was included as an additional predictor, but abuse by itself remained no longer significant when the three particular types of CM were added (t = −0.87, p = .38).

Coefficients of the four tested regression models are displayed in Table 2. While remaining significant predictors, coefficients of all CM classes were reduced when PTSD symptoms and self-esteem were included in the model, indicating some possible mediational relationships between the variables.

Table 2.

Coefficients of tested regression models predicting disordered eating

| B | SE | ß | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Constant | 0.58 | 0.03 | |

| Gender | 0.60 | 0.04 | .26*** | |

| 2 | Constant | 0.50 | 0.03 | |

| Gender | 0.57 | 0.04 | .25*** | |

| Emotional abuse | 0.44 | 0.07 | .11*** | |

| Sexual abuse | 0.68 | 0.12 | .10*** | |

| Polyvictimization | 0.49 | 0.10 | .09** | |

| 3 | Constant | 0.47 | 0.03 | |

| Gender | 0.55 | 0.04 | .24*** | |

| Emotional abuse | 0.35 | 0.07 | .09*** | |

| Sexual abuse | 0.53 | 0.13 | .08*** | |

| Polyvictimization | 0.32 | 0.10 | .06** | |

| PTSD | 0.12 | 0.02 | .11*** | |

| 4 | Constant | 2.41 | 0.17 | |

| Gender | 0.50 | 0.04 | .22*** | |

| Emotional abuse | 0.23 | 0.07 | .06** | |

| Sexual abuse | 0.44 | 0.12 | .06*** | |

| Polyvictimization | 0.24 | 0.10 | .04* | |

| PTSD | 0.07 | 0.02 | .07** | |

| Self-esteem | −0.06 | 0.01 | −.21*** | |

N = 2875; R2 = .07 for Step 1, ΔR2 = .03 for Step 2 (p < .001), ΔR2 = .01 for Step 3 (p < .001), ΔR2 = .04 for Step 4 (p < .001). * p = .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

Mediation Analyses

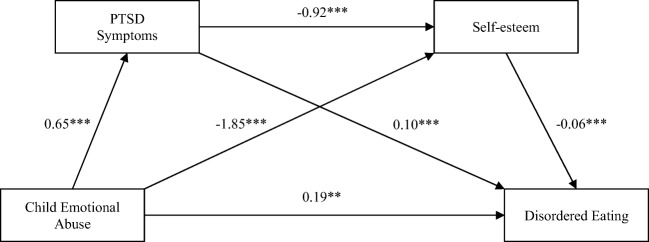

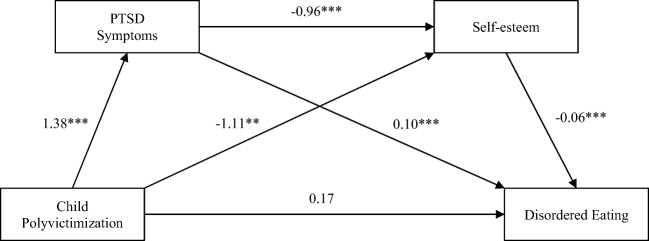

Figures 1, 2, and 3 depict the calculated mediator models for the effect of each CM class on DE separately. All total effects c between the distinct CM classes and DE were positive and statistically significant: CEA (B = 0.40, SE = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.26, 0.54]), CSA (B = 0.60, SE = 0.12, 95% CI = [0.36, 0.85]), CPV (B = 0.45, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = [0.26, 0.65]). After including the mediator effects, the direct paths c’ between CEA and DE (B = 0.19, SE = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.33]) and CSA and DE (B = 0.37, SE = 0.12, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.61]) were reduced but remained significant, suggesting partial mediation. In the CEA model, after the direct effect of CEA on DE the indirect effect of CEA on DE via self-esteem was second strongest (B = 0.11, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.16]), whereas in the CSA model, after the direct effect of CSA on DE the indirect effect via PTSD was second strongest (B = 0.11, SE 0.03, 95% CI = [0.06, 0.18]). After adjusting for the mediators in the CPV model the direct effect of CPV on DE turned nonsignificant (B = 0.17, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = [−0.03, 0.37]), indicating that the effect of CPV on DE was fully mediated via PTSD and self-esteem. The indirect effect of CPV on DE via PTSD symptoms turned out to be strongest (B = 0.14, SE = 0.04, 95% CI = [0.07, 0.21]).

Fig. 1.

Mediational model showing the influence of emotional abuse on disordered eating as mediated by PTSD and self-esteem with gender as covariate. Note. N = 2875; R2 = .14, F(4, 2870) = 117.69, p < .001; total effect c = 0.40*** indirect effects of emotional abuse on disordered eating via: PTSD symptoms (c-c’) = 0.07*; self-esteem (c-c’) = 0.11*; PTSD symptoms and self-esteem (c-c’) = 0.04*; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Fig. 2.

Mediational model showing the influence of sexual abuse on disordered eating as mediated by PTSD and self-esteem. Note. N = 2875; R2 = .14, F(4, 2870) = 118.24, p < .001; total effect c = 0.60*** indirect effects of sexual abuse on disordered eating via: PTSD symptoms (c-c’) = 0.11*; self-esteem (c-c’) = 0.06*; PTSD symptoms and self-esteem (c-c’) = 0.07*; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Fig. 3.

Mediational model showing the influence of polyvictimization on disordered eating as mediated by PTSD and self-esteem. Note. N = 2875; R2 = .14, F(4, 2870) = 116.47, p < .001; total effect c = 0.45***; indirect effects of polyvictimization on disordered eating: via PTSD (c-c’) = 0.14*; via self-esteem (c-c’) = 0.07*; via PTSD and self-esteem (c-c’) = 0.08*; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Discussion and Limitations

The aim of the current study was to investigate if there were differential associations between diverse experiences of CM and DE in early adulthood. There was support for the first hypothesis that all three specified abuse types – CEA, CSA and CPV – were associated with a significant higher level of DE than the non-abused class, which was confirmed by both comparing the percentage of individuals belonging to the DE risk-group in each CM class, as well as by examining differences between CM classes in their continuous DE scores. Not directly related to the first hypotheses, but congruent with the existing literature, all three abuse classes were associated with significant higher rates of PTSD symptoms (e.g. Gal and Basford 2015; Vranceanu et al. 2007) and lower self-esteem (e.g. Becker and Grilo 2011).

Contrary to the prediction of the second hypothesis, there were no significant differences in the association of the three abuse classes with DE. Though when comparing the distribution of participants from each CM class among DE risk- versus non-risk-group, the greatest portion of individuals considered to suffer from high levels of DE and to be at high risk for ED development was found among individuals of the CSA class. Due to the inconsistency of previous findings, no directional hypothesis was made, which CM class would be most strongly associated with DE. However, since CPV has frequently been associated with more severe psychopathology than single type abuse (Cloitre et al. 2009; Steine et al. 2017), one could have expected the highest level of DE among the CPV instead of the CSA class. Polyvictimization was conceptualized in the present study as multiple types of victimization irrespective of their duration or frequency, thus reflecting CM breadth rather than depth. However, there is no consensus whether this form of polyvictimization is more adverse than multiple victimizations of a single type of abuse (Hasselle et al. 2017). Since duration or frequency of CM incidences was not controlled for, it could be possible that participants of the CSA class were exposed to multi-incidence abuse to a greater extent than the CPV class.

The three CM classes did not differ substantially in their predictive value as it was shown in the regression analysis. When participants’ level of PTSD symptoms and self-esteem were included in the regression model, regression coefficients of all CM classes were reduced, suggesting that these variables were related to each other in a more complex way.

We, therefore, specified and estimated three mediation models, that examined the influence of each CM class separately on DE accounting for mediational effects via PTSD and self-esteem. Supporting our third hypothesis, PTSD and self-esteem each appeared to be significant mediators of this relationship in all models and above that, the indirect effect via PTSD and self-esteem in a serial order turned out to be statistically significant as well. That means that CM was not only associated with an increase of DE by itself, but also with a higher level of PTSD symptoms and lower self-esteem. A higher level of PTSD symptoms was related to a higher level of DE, whereas a higher self-esteem was related to a lower level of DE. These results might provide a possible explanation for the high comorbidity of PTSD and EDs in traumatized individuals (Brewerton 2007) and support our assumption that a person’s global self-esteem is negatively affected by traumatic events in childhood. DE can be regarded as an effort to cope with a low self-esteem (Starrs et al. 2017) and/or with intense distress and experiences associated with that distress as they are caused by a traumatic event (Hund and Espelage 2006). Moreover, a higher level of PTSD symptoms was associated with a lower-self-esteem, thus having an additional impact on DE. It may be possible that individuals with a history of CM experience fluctuations in self-esteem depending on their overall mental condition, which varies in the presence of PTSD symptoms as a function of exposure to trauma-related triggers and intrusive experiences (Kashdan et al. 2006). It is, therefore, likely to assume that the presence of PTSD symptoms may further decrease the traumatized individual’s already damaged self-esteem by reinforcing feelings of ineffectiveness, helplessness, and uselessness (Mann et al. 2004).

In case of CEA and CSA, PTSD symptoms and self-esteem partially mediated the effect of the abuse type on DE, even though the direct effects remained largest. In case of CPV, its impact on DE was fully mediated with the indirect effect via PTSD being largest. Self-esteem appeared to play a more important role in mediating the impact of CEA on DE, while PTSD was of greater importance in the CSA and CPV models.

Consequently, all CM classes were associated with increased levels of DE compared to the non-abused class, and although CEA, CSA, and CPV did not differ significantly in their association with DE, there were considerable differences in the way this association came about via PTSD symptoms and self-esteem.

Results of the current study have to be interpreted in light of certain limitations. Due to the correlational nature of the present findings, we cannot draw any causal conclusions regarding the role of CM, PTSD symptoms, or self-esteem as risk factors for DE and consequently ED development. Furthermore, DE represents a complex pattern of human behavior that may be motivated by many different factors besides the investigated variables, which were not incorporated into the present study design. For instance, other childhood adversities (e.g. interpersonal loss, witnessing intimate partner violence) have been identified as risk factors for DE (Johnson et al. 2002) and some symptoms observed in maltreated children possibly are results of environmental risk factors (e.g. poverty, community violence) rather than of the abuse itself (Hecht and Hansen 2001). There is a variety of other factors associated with both CM and DE that may function as mediators of this relationship.

Another limitation that basically affects all constructs of the study, is that all variables have been measured via self-report in a face-to-face or telephone interview, thereby leaving some space for participants’ subjective interpretations whether certain types of maltreatment or psychopathological symptoms had occurred to them. Due to the sensitive nature of these topics, reports may have been biased because of participants’ shame or fear of social taboos. The computer-assisted interview method was considered to help to resolve the problem of potential underreporting (May-Chahal and Cawson 2005), as well as the greater anonymity of interviews conducted via telephone. In terms of CM, we used precise descriptions of diverse maltreatment incidences instead of asking respondents for physical abuse or emotional abuse per se to decrease recall difficulties.

However, it is difficult to compare results of the current study to other studies that investigated the same variables but with different definitions. Men have been neglected in eating-related research for a long time (Ricciardelli 2017). Although it is a strength of our study to investigate the association between CM classes and DE in a representative sample with an equal gender distribution of participants, it has to be noted that the RiBED-8 questionnaire, of which most of the items of the DE scale were derived, is biased in some way towards male participants (Waaddegaard et al. 2003). The authors of the RiBED-8 admit that some male risk behaviors (e.g. strive for muscle building) that differ from female eating behaviors to some extent are probably overlooked by the questionnaire. Young adulthood appears to be an especially convenient period to study associations between CM and DE, since the precision of CM assessment depends to a certain degree on the time interval between the events’ occurrence and recall (Christoffersen et al. 2013) and young adults are considered a high risk-group for DE (Hasselle et al. 2017; Jacobi et al. 2011). The representativeness of the study sample may be limited by the artificially increased number of child protection cases which may have led to a higher prevalence of CM. Irrespective of its prevalence and child-protection or non-child-protection status only subjectively reported CM experiences were used for the classification of participants into CM classes. Apart from that, it is questionable whether findings from a Danish sample of young adults are generalizable across different cultures and age groups.

Nonetheless, several implications can be derived from the correlational results of the present study since both PTSD symptoms and a low self-esteem constitute important targets for treatment. When dealing with CM survivors exhibiting DE or with ED patients having a history of CM, therapists should consider the adaptive function that symptoms may serve in the individual’s life (Hund and Espelage 2006), because it is unlikely to successfully treat one problem without mentioning the other (Holzer et al. 2008). If the primary function of DE is the regulation of trauma-related negative affect and tension (that may be present in PTSD symptoms) and therapy is targeted on a reduction of DE behaviors without addressing and processing the trauma and teaching the individual adaptive coping skills, previously avoided trauma-related distress increases, and other impulsive behaviors are likely to take over the function of DE symptoms (Hund and Espelage 2006). As DE is much more prevalent than diagnosed EDs and can be considered as a pre-stage for an even more pathological development, intervention should start as early as possible. As the association between CM and DE is at least partially mediated via self-esteem, consistent strengthening of self-esteem among maltreated children might possibly prevent some of the abuse’s dysfunctional long-term consequences (O'Dea 2004).

As the present results are of correlational nature, longitudinal studies are needed to actually differentiate between correlates, risk factors, and maintaining factors in the relationship between CM and eating psychopathology. In the current study the relationship between CM and DE appeared to be not only direct, but either partially (for CEA and CSA) or fully (for CPV) mediated via PTSD symptoms and self-esteem. This indicates complex psychological processes intervening between CM experiences and DE in adulthood. Future research should investigate the role of other potential mediators or combinations of mediating variables that may influence this association beyond those factors investigated in this study or previous ones (e.g. Burns et al. 2012; Feinson and Hornik-Lurie 2016; Hund and Espelage 2006; Mills et al. 2015; Moulton et al. 2015). Kent and Waller (2000) call for the development of a conceptual and practical framework of the relationship(s) between CM and eating psychopathology, including mediating factors, as they may constitute important targets for intervention. The present findings support what was known before: CM is associated with eating psychopathology. They extend existing knowledge by differentiating between different classes of abused individuals with different CM experiences and investigating the role of PTSD symptoms and self-esteem in their relationship to DE.

Conclusion

This study set out to investigate relationships between different experiences of CM and DE in adulthood. Findings support what has been previously established: Abused individuals were more likely to suffer from DE than non-abused individuals. They extend existing knowledge by differentiating between three classes of abused individuals with different CM experiences and investigating the role of PTSD symptoms and self-esteem in their relationship to DE, thus identifying possible targets for treatment of eating disordered individuals with a history of CM. Although no specific class of CM experiences stood out as being most strongly associated with DE, they differed in how their relationship with DE was mediated via PTSD symptoms and self-esteem, with partial mediation in case of CEA and CSA and full mediation of the effect of CPV. While self-esteem appeared to be more relevant in combination with CEA, PTSD symptoms were of greater importance in the context of CSA or CPV. Future longitudinal research ought to focus on the identification of additional factors that may be part of a broader risk model, explaining under which circumstances and under contribution of which factors CM specifically leads to the development of eating psychopathology in adulthood.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Disclosure of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical norms for Nordic Psychologists and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

References

- Afifi TO, Sareen J, Fortier J, Taillieu T, Turner S, Cheung K, Henriksen CA. Child maltreatment and eating disorders among men and women in adulthood: Results from a nationally representative United States sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2017;50(11):1281–1296. doi: 10.1002/eat.22783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):724–731. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Elklit A, Christoffersen MN. A latent class analysis of childhood maltreatment: Identifying abuse typologies. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2014;19(1):23–39. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2012.734205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C, Müllerová J, Fletcher S, Lagdon S, Burns CR, Robinson M, Robinson J. Assessing childhood maltreatment and mental health correlates of disordered eating profiles in a nationally representative sample of English females. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2016;51(3):383–393. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1154-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DF, Grilo CM. Childhood maltreatment in women with binge-eating disorder: Associations with psychiatric comorbidity, psychological functioning, and eating pathology. Eating and Weight Disorders. 2011;16(2):e113–e120. doi: 10.1007/BF033253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB. Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development. 1998;69(4):1171–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland JY, Donalson R, Dinh JV, Maguen S. Trauma exposure and disordered eating: A qualitative study. Women & Health. 2017;58(2):160–174. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2017.1282398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD. Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eating Disorders. 2007;15(4):285–304. doi: 10.1080/10640260701454311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke L, Mussap AJ. Brief report: Maltreatment in childhood and body concerns in adulthood. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;18(5):620–626. doi: 10.1177/1359105312454036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns EE, Fischer S, Jackson JL, Harding HG. Deficits in emotion regulation mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and later eating disorder symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Bewell C, Blackmore E, Woodside DB. The impact of childhood sexual abuse in anorexia nervosa. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30(3):257–269. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen MN, Armour C, Lasgaard M, Andersen TE, Elklit A. The prevalence of four types of childhood maltreatment in Denmark. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2013;9:149–156. doi: 10.2174/1745017901309010149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, Petkova E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adulthood cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(5):399–408. doi: 10.1002/jts.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A, Clerici M, Caslini M, Gaudio S, Serino S, Riva G, Carrà G. Predictors of initiation and persistence of recurrent binge eating and inappropriate weight compensatory behaviors in college men. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2016;49(6):581–590. doi: 10.1002/eat.22535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A, Timko A, Serino S, Riva G, Clerici M, Carrà G. Prospective psychosocial predictors of onset and cessation of eating pathology amongst college women. European Eating Disorders Review. 2016;24(3):251–256. doi: 10.1002/erv.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinson M, Hornik-Lurie T. Binge eating and childhood emotional abuse: The mediating role of anger. Appetite. 2016;105:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Stojek M, Hartzell E. Effects of multiple forms of childhood abuse and adult sexual assault on current eating disorder symptoms. Eating Behaviors. 2010;11(3):190–192. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuemmeler BF, Dedert E, McClernon FJ, Beckham JC. Adverse childhood events are associated with obesity and disordered eating: Results from a U.S. population-based survey of young adults. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(4):329–333. doi: 10.1002/jts.20421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal G, Basford Y. Child abuse and adult psychopathology. In: Lindert J, Levav I, editors. Violence and mental health: Its manifold faces. Dordrecht: Springer; 2015. pp. 89–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Ferguson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groleau P, Steiger H, Bruce K, Israel M, Sycz L, Ouellette A-S, Badawi G. Childhood emotional abuse and eating symptoms in bulimic disorders: An examination of possible mediating variables. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45(3):326–332. doi: 10.1002/eat.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt AA. Purging behaviors. In: Wade T, editor. Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 704–707. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselle AJ, Howell KH, Dormois M, Miller-Graff LE. The influence of childhood polyvictimization on disordered eating symptoms in emergng adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;68:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analyses: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht DB, Hansen DJ. The environment of child maltreatment: Contextual factors and the development of psychopathology. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6(5):433–457. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00015-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirth JM, Rahman M, Berenson AB. The association of posttraumatic stress disorder with fast food and soda consumption and unhealthy weight loss behaviors among young women. Journal of Woman’s Health. 2011;20(8):1141–1149. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer SR, Uppala S, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Simonich H. Mediational significance of PTSD in the relationship of sexual trauma and eating disorders. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(5):561–566. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hund AR, Espelage DL. Childhood emotional abuse and disordered eating among undergraduate females: Mediating influence of alexithymia and distress. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30(4):393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymowitz G, Salwen J, Salis KL. A mediational model of obesity related disordered eating: The roles of childhood emotional abuse and self-perception. Eating Behaviors. 2017;26:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomaa R, Backholm K, Birgegård A. Posttraumatic stress disorder in eating disorder patients: The roles of psychological distress and timing of trauma. Psychiatry Research. 2015;230(2):506–510. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Fittig E, Bryson SW, Wilfley D, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Who is really at risk? Identifying risk factors for subthreshold and full syndrome eating disorders in a high risk sample. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(9):1939–1949. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaras KN, Hudson JI. Epidemiology of eating disorders. In: Wade T, editor. Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 362–366. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Childhood adversities associated with risk for eating disorders or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):394–400. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Uswatte G, Steger MF, Julian T. Fragile self-esteem and affective instability in posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44(11):1609–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent A, Waller G. Childhood emotional abuse and eating psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(7):887–903. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent A, Waller G, Dagnan D. A greater role of emotional than physical or sexual abuse in predicting disordered eating attitudes: The role of mediating variables. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;25(2):159–167. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199903)25:2<159::AID-EAT5>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Greif Green J, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO world mental health surveys. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197(5):378–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong S, Bernstein K. Childhood trauma as a predictor of eating psychopathology and its mediating variables in patients with eating disorders. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18(13):1897–1907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lix LM, Keselman JC, Keselman HJ. Consequences of assumption violations revisited: A quantitative review of alteratives to the one-way analysis of variance F test. Review of Educational Research. 1996;66(4):579–619. doi: 10.3102/00346543066004579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mann M, Hosman CH, Schaalma HP, de Vries NK. Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Education Research. 2004;19(4):357–372. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SM, Flint AJ, Field AE, Austin SB, Rich-Edwards JW. Abuse victimization in childhood or adolescence and risk of food addiction in adult women. Obesity Research. 2013;21(12):e775–e781. doi: 10.1002/oby.20500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May-Chahal C, Cawson P. Measuring child maltreatment in the United Kingdom: A study of the prevalence of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:969–984. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzeo SE, Espelage DL. Association between childhood physical and emotional abuse and disordered eating behaviors in female undergraduates: An investigation of the mediating role of alexithymia and depression. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49(1):86–100. doi: 10.1037//0022-0167.49.1.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills P, Newman EF, Cossar J, Murray G. Emotional maltreatment and disordered eating in adolescents: Testing the mediating role of emotion regulation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;39:156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Schlesinger MR, Brewerton TD, Smith BN. Comorbidity of partial and subthreshold PTSD among men and women with eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication Study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45(3):307–315. doi: 10.1002/eat.20965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton SJ, Newman E, Power K, Swanson V, Day K. Childhood trauma and eating psychopathology: A mediating role for dissociation and emotion regulation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;39:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dea JA. Evidence for a self-esteem approach in the prevention of body image and eating problems among children and adolescents. Eating Disorders. 2004;12(3):225–239. doi: 10.1080/10640260490481438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J. The psychology of eating: From healthy to disordered behavior. 2. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Kim HK, Fisher PA. Psychosocial and cognitive functioning of children with specific profiles of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(10):958–971. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignatelli AM, Wampers M, Loriedo C, Biondi M, Vanderlinden J. Childhood neglect in eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2017;18(1):100–115. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2016.1198951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike KM, Striegel-Moore RH. Disordered eating and eating disorders. In: Gallant SJ, Keita GP, Royak-Schaler R, editors. Health care for women: Psychological, social, and behavioral influences. Washigton, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Cameron RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9(1):9–14. doi: 10.1185/135525703125002360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli LA. Eating disorders in boys and men. In: Wade T, editor. Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Hendin HM, Trzesniewski KH. Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(2):151–161. doi: 10.1177/0146167201272002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs-Ericsson N, Keel PK, Holland L, Selby EA, Verona E, Cougle JR, Palmer E. Parental disorders, childhood abuse, and binge eating in a large community sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45(3):316–325. doi: 10.1002/eat.20938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanlier N, Varli SN, Macit MS, Mortas H, Tatar T. Evaluation of disordered eating tendencies in young adults. Eating and Weight Disorders. 2017;22(4):623–631. doi: 10.1007/s40519-017-0430-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolak L, Murnen SK. A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between child sexual abuse and eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Dsorders. 2002;31(2):136–150. doi: 10.1002/eat.10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Heron KE, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Thompson KM. The influence of reported trauma and adverse events on eating disturbance in young adults. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(3):195–202. doi: 10.1002/eat.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starrs CJ, Dunkley DM, Moroz M. Self-criticism and low self-esteem. In: Wade T, editor. Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 746–751. [Google Scholar]

- Steine IM, Winje D, Krystal JH, Bjorvatn B, Milde AM, Grønli J, et al. Cumulative childhood maltreatment and its dose-response relation with adult symptomatology: Findings in a sample of adult survivors of sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;65:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Fehon DC, Andres-Hyman RC, Lipschitz DS, Grilo CM. Differential relationships of childhood abuse and neglect subtypes to PTSD symptom clusters among adolescent inpatients. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(2):229–239. doi: 10.1002/jts.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultson H, Kukk K, Akkermann K. Positive and negative emotional eating have different associations with overeating and binge eating: Construction and validation of the positive-negative emotional eating scale. Appetite. 2017;116:423–430. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagay S, Schlegl S, Senf W. Traumatic events, posttraumatic stress symptomatology and somatoform symptoms in eating disorder patients. European Eating Disorders Review. 2010;18(2):124–132. doi: 10.1002/erv.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagay S, Schlottbohm E, Reyes-Rodriguez ML, Repic N, Senf W. Eating disorders, trauma, PTSD, and psychosocial resources. Eating Disorders. 2014;22(1):33–49. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2014.857517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ. Eating disorder or disordered eating? Non-normative eating patterns in obese individuals. Obesity Research. 2004;12(9):1361–1366. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasca GA, Ritchie K, Zachariades F, Proulx G, Trinneer A, Balfour L, et al. Attachment insecurity mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and eating disorder psychopathology in a clinical sample: A structural equation model. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:926–933. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CB. Weight and shape concern and body image as risk factors for eating disorders. In: Wade T, editor. Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 889–893. [Google Scholar]

- Vranceanu A-M, Hobfoll SE, Johnson RJ. Child multi-type maltreatment and associated depression and PTSD symptos: The role of social support and stress. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(1):71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waaddegaard M, Thoning H, Petersson B. Validation of a screening instrument for identifying risk behaviour related to eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review. 2003;11(6):433–455. doi: 10.1002/erv.537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Thompson KM, Redlin J, Demuth G, et al. Eating disturbance and sexual trauma in childhood and adulthood. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30(4):401–412. doi: 10.1002/eat.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]