Abstract

Population health scientists have largely overlooked anticipatory stressors and how different groups of people experience and cope with anticipatory stress. I address these gaps by examining black-white differences in the associations between an important anticipatory stressor—goal-striving stress (GSS)— and several measures of psychophysiology. Hypotheses focusing on racial differences in GSS and psychophysiology are tested using self-report and biomarker data from the Nashville Stress and Health Study (2011–2014), a cross-sectional probability survey of black and white working-age adults from Davidson County, Tennessee (n=1,252). Compared to their white peers, blacks with higher GSS report greater self-esteem and fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, increased GSS also predicts elevated levels of high-effort coping (i.e., John Henryism), HPA axis activity, and blood pressure for blacks but not whites. I discuss the implications of these findings for scholars interested in the stress process and broader black-white health inequalities in the United States.

Keywords: stress process, anticipatory stress, goal-striving stress, John Henryism, high-effort coping, skin-deep resilience, black-white health paradox, psychophysiology, HPA axis, blood pressure

The stress process paradigm conceives of individual health outcomes as resulting from a dynamic interplay between a person’s various social statuses, stress exposures, and coping resources and strategies (Pearlin et al. 1981). Stressors refer to circumstances that require people to respond in ways that deplete their adaptive capacities and are typically conceptualized as being either acute (e.g., major life events) or chronic (e.g., financial hardship) in nature (Turner, Wheaton, and Lloyd 1995). Effective coping is also thought to mitigate the adverse health effects of stressors. The conventional wisdom in the coping literature is that people who enlist proactive coping strategies tend to experience better health than their peers with more passive or avoidant coping styles (Pearlin and Bierman 2013).

Despite considerable progress in our understanding of the stress process, important issues in this area of study remain unresolved. For one, the consequences of anticipatory stressors have been mostly overlooked. Unlike concrete events and strains, anticipatory stressors “do not exist as realities but are viewed as having the potential to become so” (Pearlin and Bierman 2013: 328). The neglect of anticipatory stressors is troubling given that human beings appear to be uniquely susceptible to anticipatory distress when compared to other non-human animals. Indeed, the human brain has evolved highly complex cortical structures capable of anticipating and responding to a wide variety of environmental stimuli (Massey 2001; Barrett 2017). Although adaptive in the short term, our brain’s ability to anticipate calamities can also become hyperactive and problematic for health over time (Sapolsky 1998; O’Donovan et al. 2012). This appears to be especially true for people occupying precarious socioeconomic positions who must remain hypervigilant to cues of impending adversity (Wilson and Mossakowski 2009; Pearlin and Bierman 2013).

Another shortcoming of the stress process literature is that researchers rarely consider how different social groups experience and attribute various meanings to the same psychosocial stressor (McLeod 2012; Pearlin and Bierman 2013). As McLeod (2012: 176) points out, the vast majority of stress process research has focused on “objective social origins of distress,” or how macro-level social arrangements influence group differences in stress exposures, available coping resources, and health outcomes. This methodological focus is narrow, however, because it assumes the same stressor will entail identical meanings and experiences for different groups of people.

The “black-white health paradox” in the United States serves as an illustrative case study of these unresolved ambiguities of stress and coping (see Hummer and Hamilson 2019; Louie and Wheaton 2019). Population health scientists have noted for decades that white Americans, despite enjoying considerable structural and material advantages, tend to experience greater emotional distress than their black peers when faced with the same psychosocial stressor (Kessler 1979; Malat, Mayorga-Gallo, and Williams 2017). At the population level, whites also exhibit higher rates of psychiatric disorders like major depression, anxiety, suicide, and substance dependence. Nevertheless, blacks are still significantly more likely than whites to die prematurely from cardiometabolic disease, cancer, and other chronic health conditions. Although several explanations have been offered, the jury is still out concerning the underlying mechanisms responsible for this paradox (Hummer and Hamilton 2019: 151–154).

The present study addresses these gaps in our knowledge of the stress process and black-white health inequalities in the United States. Drawing from literatures on anticipatory stress and racial differences in coping, I contend that the black-white health paradox at least partially stems from how black and white Americans are socialized to anticipate failure. Most white Americans are socialized to perceive themselves as atomized individuals acting within a fully meritocratic society (Kraus et al. 2012; Bonilla-Silva 2017), and thus tend to experience severe psychological distress whenever they confront unfair treatment or structural barriers to their aspirations (Hicken, Lee, and King 2018; Malat et al. 2017). Black Americans, on the other hand, are socialized to develop contextualized self-concepts that are better attuned to external environments and social constraints (Coard and Sellers 2005; Brown 2008; Bentley, Adams, and Stevenson 2008; Kraus et al. 2012). While this unique socialization process can bolster psychosocial resilience in the face of barriers to attainment (Barbarin 1993; Fischer and Shaw 1999; Brown 2008), it can also promote high-effort coping strategies that tax physiological stress responses and eventually lead to poor physical health (James 1994; Gaydosh et al. 2018).

In what follows, I first introduce a neglected survey measure of anticipatory stress: the goal-striving stress (GSS) scale. I then develop hypotheses for why black and white Americans should experience GSS in fundamentally different ways and thereby express distinct stress and coping processes. Next, I test my study hypotheses with rich self-report and biomarker data from the Nashville Stress and Health Study (2011–2014), a probability survey of non-Hispanic black and white working-age adults from Davidson County, Tennessee (n=1,252). My analyses reveal substantial black-white disparities in the associations between GSS and self-esteem, high-effort coping, psychological distress, HPA axis hormones, and blood pressure. I close by discussing the implications of my findings for scholars concerned with the stress process and black-white health inequalities in the United States.

BACKGROUND

Goal-Striving Stress

The GSS scale measures the perceived gap between a person’s current achievements and aspirations and weights this gap by their desire for and anticipation of future success. Someone with high GSS perceives a sizable achievement-aspiration gap, would be highly disappointed by failure, but anticipates a low probability of future success. Sociologists Seymour Parker and Robert Kleiner (1966) originally developed the GSS scale to measure the psychosocial strains experienced by black Americans striving for upward mobility in the wake of desegregation and the civil rights movement. Fundamentally, Parker and Kleiner appeared to be responding to what W.E.B. Du Bois intimated decades earlier in The Philadelphia Negro, which was that ongoing experiences with “unrewarded merit and reasonable but unsatisfied ambition” were unique social causes of distress for emancipated black Americans (Du Bois 1899: 351).

The GSS scale is an augmented version of Hadley Cantril’s (1965) self-anchored striving scale. The basic method is to show respondents an image of a 10-rung ladder and instruct them to imagine that the bottom and top rungs represent their “worst” and “best” possible ways of life, respectively. Respondents are then asked to report where on the ladder they perceive themselves to be now and where they expect to be in the future. The idea, in Cantril’s words, was to construct a measure of social status “anchored within an individual’s own reality world” (Cantril 1965: 25). Akin to other validated and widely implemented scales of subjective well-being (e.g., Scheier and Carver 1985), self-anchored striving scales measure a person’s cognitive averaging of their current achievements and aspirations relative to broader sociocultural referents for success (Andersson 2015).

Although they share fundamental characteristics, the GSS scale diverges from Cantril’s scale in notable ways. First, the GSS scale also measures the emotional valence respondents attach to their goals by asking them how disappointed they would be by failure. This added component is informative because merely asking respondents to rank their achievements and aspirations does not directly account for feelings of relative deprivation or how strongly respondents desire to bridge their achievement-aspiration gap (see Smith et al. 2012). For instance, someone could very well acknowledge that their current social ranking is inferior to an idealized reference group (e.g., millionaires) and may even entertain pipe dreams about one day joining this group themselves, but they could still feel content with their lot and therefore lack any real motivation to achieve higher status in the coming years.

Second, the GSS scale also accounts for the anticipation of failure by asking respondents to report their subjective likelihood of future success. This added item is what makes the GSS scale a distinctly sociological measure of individual goal pursuit vis-à-vis perceived opportunity structures. Emile Durkheim ([1897] 1951) was perhaps the first sociologist to identify dysregulated goal pursuits as unique social determinants of population well-being. Durkheim suggested that one role of society is to regulate individual ambitions by preserving a harmony between culturally prescribed goals and the socially structured means of attainment. Whenever a given society loses its ability to effectively channel individual aspirations toward desired social outcomes, many people will begin to suffer from profound feelings of normlessness and despair (see also Agnew 1997).

Robert Merton (1938, 1968) advanced Durkheim’s work by describing the individual effects of thwarted goals in more detail. Merton (1938: 38) suggested, in a nutshell, that many behaviors and emotions we label as deviant are predictable responses to the “dissociation between culturally defined aspirations and socially structured means.” In subsequent work, Merton (1968) would then elaborate on why the sociocultural environment of the United States is a breeding ground for strained ambitions and failure. The United States is peculiar, Merton noted, because our dominant success ethos—namely, the “American Dream” ideology—universally prescribes all citizens to strive for material gain while negating the reality that opportunity structures block many hardworking people from achieving success based on their ascribed statuses of race, gender, and familial social class. According to Merton, these sociocultural contradictions should create psychosocial strains for many people and ultimately push them toward maladaptive coping behaviors (see also Messner and Rosenfeld 2001; McNamee and Miller 2014).

Despite its clear affinities with sociological theory, sociologists entirely ignored the GSS scale until only very recently. Within the past decade, a small group of sociologists and epidemiologists have reinvigorated research into GSS, linking high levels of GSS to increased psychological distress (Sellers and Neighbors 2008; Neighbors et al. 2011; DeAngelis and Ellison 2018), weakened self-concept (DeAngelis 2018), subjective social isolation (DeAngelis and Ellison 2018), and physiological dysregulation (Sellers et al. 2012; Cain et al. 2019). However, we still know very little about black-white differences in the effects of GSS. One study found that GSS predicted worse mental health for whites than blacks (Neighbors et al. 2011), but this study could not resolve whether GSS also predicted black-white differences in physiology. A second study found that GSS was associated with more self-reported physical health problems for Caribbean blacks than whites and African Americans (Sellers et al. 2012), but this study found no racial differences in the associations between GSS and blood pressure or BMI. These unresolved issues are important to rectify because, as I demonstrate in the following section, there are good reasons to believe GSS will predict worse psychological functioning for whites but worse physiological functioning for blacks.

Race and the Psychophysiology of Goal Pursuit

Before continuing, I should note that my study is not concerned with whether average levels of exposure to GSS vary for blacks and whites. In this sense, I expect blacks to exhibit higher average levels of GSS than whites given blacks are exposed to more barriers to attainment. Rather, the present study is focused on how blacks and whites differ in their experiences and styles of coping with equal levels of GSS, and how such differences might surface as unique psychophysiological profiles (see Kessler 1979).

GSS is intimately linked to the self-concept (DeAngelis 2018). According to the self-attribution principle, people derive their sense of competence and self-worth through repeated opportunities to materialize life goals (Rosenberg 1986). That is, personal experiences over the life course condition people to attribute their successes and failures either to their own agency or to powerful external forces (Pearlin and Schooler 1978). But individual self-attributions do not occur within a vacuum—people also take cues from the larger society and learn how to interpret their strivings in accordance with broader cultural schemas about who succeeds and why (Rosenberg 1986: 76; Skaff and Gardiner 2003). This latter point is important to remember because the dominant success myths in the United States admonish individuals to assume sole responsibility for their life outcomes, thereby glossing over the presence of structural barriers to attainment (Merton 1968; Hochschild 1995; McNamee and Miller 2014).

Although dominant success narratives in the United States often undergird white supremacism—indeed, the same meritocratic principles underlying the American Dream have been used for centuries to demonstrate the supposed inferiority of racial minorities (Feagin 1975; Bobo, Kluegel, and Smith 1997)—these same narratives can also become oppressive for whites who feel they are failing. Ironically, many whites buy into meritocratic ideals with such strong conviction that they become blinded to broader class-based structures impinging on their aspirations (Malat et al. 2017; Metzl 2019). This is because whites historically have enjoyed the luxury of being able to perceive themselves as unfettered individuals in a free society rather than as members of an oppressed group, a structural advantage that makes meritocratic principles appear all the more compelling to them (Kraus et al. 2012; Bonilla-Silva 2017). Consequently, whites who are failing to achieve their goals should be more inclined to attribute their failures to their own shortcomings, which could lead to feelings of lowliness and incompetence (DeAngelis 2018). For struggling whites who do eventually accept that their aspirations are beyond their control, this grudging acceptance may usher in a profound sense of helplessness and despair (DeAngelis and Ellison 2018).

Experiences with GSS should be markedly different for black Americans. Opportunity structures in the United States have been systematically engineered to favor whites at the expense of blacks (Rothstein 2017). Blacks are therefore poorly positioned in the stratification hierarchy to recover from thwarted goals, which means the stakes of failure tend to be much higher for blacks than whites (Malat et al. 2017). Moreover, even blacks who do manage to achieve success still have to contend with the added burden of cultural racism, or the “instillation of the ideology of [black] inferiority in the values, language, imagery, symbols, and unstated assumptions of the larger society” (Williams, Lawrence, and Davis, 2019: 110). All this is to say that, unlike whites, blacks must navigate a toxic sociocultural environment in which GSS is a permanent fixture of their lives (Parker and Kleiner 1966; Feagin and Sikes 1994).

For these reasons, blacks have adapted a unique coping orientation to navigate U.S. society in the wake of emancipation and desegregation. Sherman James referred to this coping style as “John Henryism,” which he defined as the “strong, explicit emphasis on hard work and self-reliance, and [an] equally strong but more implicit emphasis on resistance to environmental forces that arbitrarily constrain personal freedom” (James 1994: 178). Many blacks are therefore socialized from an early age to anticipate hostility from the larger society and to stick close to the black community for support (Daly et al. 1995; Brown 2008). Through this racial socialization process, blacks are also exposed to counter narratives about what it takes to “make it” in the United States, which typically account for the presence of powerful external barriers to their aspirations (Coard and Sellers 2005; Bentley et al. 2008).

Because blacks are often taught from an early age to anticipate setbacks due to forces beyond their control, they should be less likely than whites to internalize their failures or suffer emotional shock from GSS. As already mentioned, one study did indeed find that GSS predicted significantly less psychological distress for blacks than whites (Neighbors et al. 2011). Other studies have found that people who attribute their life outcomes to external forces beyond their control—be they corrupt opportunity structures or divine agency—tend to enjoy enhanced self-esteem and less psychological distress from GSS (Sellers, Neighbors, and Bonham 2011; DeAngelis 2018; DeAngelis and Ellison 2018). The takeaway from these studies appears to be that relinquishing personal responsibility for failures can help people with high GSS preserve their self-esteem (DeAngelis 2018), which can be especially helpful for marginalized groups and individuals with heavily constricted social agency (DeAngelis and Ellison 2018).

While blacks may enjoy a relative psychosocial advantage over their white peers, the concomitant physiological effects of GSS could be more sinister for blacks. An emerging literature on the “skin-deep resilience” of upwardly mobile blacks has revealed substantial physiological costs associated with enlisting proactive and high-effort coping strategies in the face of structural barriers to attainment. Studies in this field have shown that blacks who strive for upward mobility against a backdrop of socioeconomic marginalization report considerable mental acuity and resilience even as they endure physiological deterioration (see Gaydosh et al. 2018). Although such chronic and high-effort coping can affect the body in various ways (McEwen 1998), the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has been identified as a key system responsible for mediating physiological responses to anticipatory social stressors and is thus a central focus of my study (Sapolsky 1998; Goosby, Cheadle, and Mitchell 2018).

The HPA axis functions as a series of feedback loops that activate after the body’s initial fight-or-flight response to an acute stressor (see Spencer and Deak 2017). A cluster of neurons in the hypothalamus section of the brain first secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which travels to the pituitary gland where it initiates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then travels through the bloodstream to the adrenal gland where it initiates the release of cortisol. The function of cortisol is to then (a) suppress long-term bodily functions related to digestion, growth, reproduction, and inflammation, (b) redirect stores of glucose, proteins, and fatty acids back into the bloodstream, and (c) restrict blood vessels to signal the heart to pump blood harder and faster. Within a period of minutes or hours, cortisol serves the highly adaptive function of providing the body with energy to surmount stressors. Nonetheless, people who must constantly anticipate and respond to stressors over periods of weeks, months, or even years can succumb to hypercortisolism whereby the body loses its ability to effectively inhibit cortisol secretion (Saplosky 1998).

The collective realization among black Americans that their aspirations are often at the mercy of forces beyond their control could therefore be a double-edged sword. While this awareness can help buffer negative self-attributions of failures and thereby preserve critical psychosocial resources, it could also motivate high-effort coping strategies that tax physiological stress responses. Such dogged goal striving in the face of barriers to attainment could ultimately put blacks at higher risk of hypercortisolism and elevated blood pressure, both of which have been linked with chronic anticipatory distress and HPA axis dysregulation (James 1994; Sapolsky 1998; Eddy et al. 2018).

Summary of Hypotheses

According to my theoretical perspective, high levels of GSS should be associated with feelings of worthlessness and despair for whites more so than for blacks. At the same time, high levels of GSS should lead to high-effort coping and elevated physiological stress responses for blacks more so than for whites. I therefore expect to observe the following empirical patterns:

H1:

Compared to their white peers, blacks with high GSS will exhibit enhanced self-esteem, more high-effort coping, and fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety.

H2:

Compared to their white peers, blacks with high GSS will exhibit elevated HPA axis activity and blood pressure.

METHODS

Nashville Stress and Health Study

I tested my hypotheses with self-report and biomarker data from Vanderbilt University’s Nashville Stress and Health Study (NSAHS), a cross-sectional probability survey of non-Hispanic black and white working-age adults from Davidson County, Tennessee (n=1,252). The NSAHS was designed for the very purpose of analyzing black-white differences in stress, coping, and health. As NSAHS researchers noted, Nashville was an excellent location to conduct this study given its relatively high concentration of affluent blacks who are affiliated with the local historically black universities and medical schools. Sampling from Nashville therefore increased the likelihood of obtaining an adequate sample of affluent blacks, which was “crucial for disaggregating the health significance of race and [socioeconomic status]” (Turner, Brown, and Hale 2017: 25).

The NSAHS sample was collected using multistage stratified sampling techniques. Vanderbilt researchers first used simple random sampling to choose 199 block groups from within Davidson County. Survey Sampling International then generated a random list of 7,000 home addresses from this sample of block groups in proportion to population size. Vanderbilt researchers then drew four random samples (n=600 per sample) of individuals between 25 and 65 years of age. Each sample was stratified by race and gender such that half of the sample was black and half white with equal numbers of men and women represented in each racial group. 59% of contacted persons from this sampling frame ultimately agreed to participate in the study. All analyses were weighted for the probability of non-contact during the household screening phase and for non-response during the interviewing phase. Post-stratification weights were also incorporated into the final design weight to permit generalizability to Davidson County’s population of black and white working-age adults. The findings reported below were comparable regardless of weighting.

Each survey interview lasted approximately three hours. All interviews were computer-assisted and conducted either in the respondent’s home or on the Vanderbilt campus. Interviewers were professionally trained and matched with each respondent based on race. All respondents received $50 for participating in the survey phase of the interview. Respondents were also given instructions and materials during the survey interview for subsequent biomarker collection. A trained clinician visited the respondent’s home the morning following the interview to collect a urine sample, intravenous blood sample, blood pressure measurements (three measures spaced by two-minute intervals), and anthropometric measures of height, weight, and hip and waist circumferences. Respondents received an additional $50 for participating in the biomarker phase of the study. Fewer than 2% of respondents refused to participate in biomarker collection. Due to the complex design of the NSAHS, data collection lasted from April 2011 to January 2014 or roughly three years. For complete information on sampling and data collection for the NSAHS, see Turner et al. (2017).

MEASURES

Psychological Functioning.

Self-esteem was measured with Rosenberg’s (1965) scale (alpha = .81). Sample items included “You feel that you are a person of worth at least equal to others,” “You are able to do things as well as most other people,” and “All in all, you are inclined to feel that you are a failure” (reverse-scored). I assessed high-effort coping with Sherman James’ (1994) 12-item John Henryism scale (alpha = .78). Sample items included “Once I make up my mind to do something, I stay with it until the job is done,” “When things don’t go the way I want them to, that just makes me work even harder,” and “I don’t let my personal feelings get in the way of doing a job.”

Past-month depressive symptoms were measured with the 20-item CESD scale (alpha = .92). Sample items included “You felt sad,” “You felt that you could not shake off the blues,” and “You felt everything you did was an effort” (see Radloff 1977). Past-month anxiety was measured with a 5-item adaptation of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (alpha = .87). Sample items included “I felt worried over possible misfortunes,” “I felt tense,” and “I felt anxious” (e.g., Marteau and Bekker 1992). Response choices for all items were ordinal and were averaged or summed to create indices.

Physiological Functioning.

I assessed physiological functioning with biomarkers for HPA axis activity and blood pressure. HPA axis activity was measured with three biomarkers: 12-hour urinary levels of cortisol (ug/L), blood concentrations of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate or DHEAS (ug/dL), and the ratio of cortisol to DHEAS. DHEAS is another HPA axis hormone released from the adrenal gland and is an antagonist to cortisol, meaning it functions to restore bodily homeostasis in the wake of prolonged cortisol secretion. Exhibiting a simultaneous increase in cortisol and decrease in DHEAS levels could indicate hormonal instability and increasing vulnerability to the toxic effects of cortisol. Exhibiting higher increases in cortisol relative to DHEAS could also indicate that the body is preferentially producing cortisol at the expense of cortisol antagonists (see Kamin and Kertes 2017).

I also examined the average of three systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings. Systolic blood pressure gauges the pressure in the arteries while the heart is beating, and diastolic blood pressure measures the pressure in the arteries between heartbeats. All blood pressure readings were recorded in millimeters of mercury (mmHg). Blood pressure was important to consider in conjunction with HPA axis activity because, as mentioned earlier, chronic anticipatory distress and hypercortisolism also tend to be associated with cardiovascular abnormalities (Sapolsky 1998).

Goal-Striving Stress.

Interviewers showed respondents an image of a ladder with rungs numbered from 0 to 9. Respondents were told that “the steps on the ladder stand for 10 possible steps in your life. Level 9 stands for the best possible way of life for you and the first step stands for the worst possible way of life for you.” Interviewers then asked respondents, “Which step number describes where you are now?” Respondents who answered that they were currently at the top rung were not asked any follow-up questions and were given a score of 0 on GSS (n=108). All other respondents were then asked, “Will you please tell me the step number that best describes where you would like to be a few years from now?” Respondents who answered that they did not desire to reach a higher rung were not asked any follow-up questions and were also given a score of 0 on GSS (n=32).1 The next follow-up question then asked, “How likely is it that you will actually reach this [desired] step?” Response choices included highly likely (=1), somewhat likely (=2), somewhat unlikely (=3), and highly unlikely (=4). The final question asked, “How disappointed would you be if you found out that you could never reach [your desired step]?” Response choices included not at all (=1), slightly (=2), fairly (=3), and very (=4).

Following prior work, I calculated GSS scores by taking the difference between a respondent’s achieved and aspired rungs and weighting this difference by the respondent’s subjective likelihood and level of disappointment (Sellers and Neighbors 2008; Neighbors et al. 2011). To be specific, I calculated scores with the following formula: GSS = (aspired rung − achieved rung) × (high disappointment × low likelihood). To understand how this scale operates, imagine two respondents with the same achievement-aspiration gap but with divergent expectations for the future. Respondent A anchors their achievements on rung 5 and desires to reach rung 8 but says they would be “not at all disappointed” (=1) by failure and believes it is “highly likely” (=1) they will succeed. Respondent A’s GSS score would be (8–5) × (1×1) = 3×1 = 3. Respondent B also anchors their achievements on rung 5 and desires to reach rung 8 but feels it is “highly unlikely” (=4) they will succeed and would be “very disappointed” (=4) by failure. Respondent B would score (8–5) × (4×4) = 3×16 = 48 on GSS.

Race.

Categories for self-identified race included non-Hispanic black and white.

Covariates.

All regression estimates adjusted for numerous potentially confounding variables. First, I controlled for basic sociodemographic characteristics of age (in years) and gender (1=female, 0=male). Second, I controlled for childhood and other antecedent conditions, including childhood financial hardship (ordinal; 1=family could easily afford food, clothing, shelter, and lots of extras… 5=could not afford to pay for food, clothing, and shelter), parental education (ordinal; 0=no formal education…11=Doctorate degree), a 32–item checklist of major life events during childhood and adulthood, and a diagnostic checklist of lifetime psychiatric disorders. The measure of parental education referred only to the caregiver who “provided the major financial support of the family or household.” The checklist of lifetime psychiatric disorders was based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Lloyd and Turner 2008) and was measured by summing indicators of whether respondents met criteria (1=yes) for lifelong major depression, generalized anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance dependence, and social anxiety.

Third, I controlled for adulthood achieved statuses. These included marital status (1=married, 0=not married), education (in years), financial resources (standardized ordinal measures of household income, liquid assets, and value of home; alpha = .80), and employment status (unemployed=reference, full-time, part-time, retired, other). Fourth, I controlled for health behaviors, including obesity status as indicated by a BMI greater than or equal to 30 (1=obese, 0=not obese), smoker status (1=current smoker, 0=former/non-smoker), and heavy drinking (1=heavy drinker, 0=not a heavy drinker). Respondents were delineated as heavy drinkers if they indicated that they drank four or more drinks on average in the past year whenever they did drink.

Fifth, I controlled for major and daily discrimination experiences (Kessler, Mickelson, and Williams 1999). Major discrimination was constituted by a checklist of questions asking whether respondents personally experienced seven major episodes of discrimination at any point in their lives (1=yes). These episodes included being unfairly treated by the police, being discouraged by a teacher or advisor from continuing their education, and being unfairly fired or denied a promotion at work. Daily discrimination included nine items gauging how often (on a Likert scale) respondents experienced discrimination in their daily lives, such as receiving worse service than other people at restaurants or stores and being called names, insulted, threatened, or harassed by other people. I took the average of all nine responses to create a mean index (alpha = .85).

Finally, my analyses of biomarker outcomes adjusted for whether respondents took blood pressure medications (1=yes) and fasted before collection (1=did not fast, 0=fasted), as well as blood collection time (in HH:MM) and 12-hour urine collection end time (in HH:MM). Blood samples were collected once and at various times of the day, and respondents also initiated their 12-hour urine samples at various times of the day. Because HPA axis hormones generally peak shortly after awakening and then decrease into the evening (Kamin and Kertes 2017), my regression estimates of cortisol and DHEAS levels had to account for the time of specimen collection. I hypothesized above that GSS will be associated with elevated physiological stress responses for blacks, which implies that blacks with high GSS should exhibit hormonal imbalances regardless of collection time.

Analytic Strategies

I first analyzed weighted descriptive statistics of study variables split by racial group along with ANOVA and chi-square tests of black-white differences in means/proportions (Table 1). Next, I conducted a series of robust ordinary least squares (OLS) regression estimates of my dependent variables (Tables 2–5). Cortisol, DHEAS, and cortisol:DHEAS ratio were converted into natural logarithmic form to permit the use of linear regression techniques. Cortisol:DHEAS ratios can be interpreted as the (logged) number of ug/L of urinary cortisol for every ug/dL of serum DHEAS. For example, a cortisol:DHEAS ratio of 2 would mean a respondent exhibited 2 ug/L of cortisol for every 1 ug/dL of DHEAS (see Sollberger and Ehlert 2016: 392). The distributional properties of cortisol, DHEAS, and cortisol:DHEAS ratio before and after logging their distributions are provided in the online supplement (Table S10).

Table 1.

Weighted Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables: Nashville Stress and Health Study (2011–2014).

| Black (n = 627) | White (n = 625) | B≠wa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | ||

| Focal Variables | |||||||||

| Self-esteem | 4.65 | .44 | 1.83 | 5 | 4.54 | .62 | 1.17 | 5 | ** |

| John Henryism | 49.24 | 5.89 | 24 | 60 | 47.56 | 5.75 | 22 | 59 | *** |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.72 | .47 | 1 | 3.35 | 1.65 | .51 | 1 | 3.70 | * |

| Anxiety | 1.83 | .69 | 1 | 4 | 1.91 | .70 | 1 | 4 | |

| Cortisol (logged ug/L) | 2.09 | .91 | −.28 | 5.27 | 2.00 | .81 | −.07 | 4.65 | |

| DHEAS (logged ug/dL) | 4.63 | .74 | 2.56 | 6.52 | 4.79 | .74 | 2.66 | 6.77 | ** |

| Cortisol:DHEAS ratio (logged) | −2.51 | 1.04 | −5.40 | .97 | −2.79 | 1.03 | −5.88 | .88 | *** |

| Systolic blood pressure | 125.95 | 14.61 | 84.00 | 198.33 | 119.78 | 13.31 | 79.73 | 176.67 | *** |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 80.34 | 9.62 | 52.10 | 119.33 | 76.47 | 8.91 | 47.79 | 109.42 | *** |

| Goal-striving stress (scale) | 11.11 | 11.29 | 0 | 112 | 9.61 | 11.13 | 0 | 96 | * |

| Low (reference) | .20 | .40 | 0 | 1 | .29 | .45 | 0 | 1 | ** |

| Middle | .40 | .49 | 0 | 1 | .39 | .49 | 0 | 1 | |

| High | .40 | .49 | 0 | 1 | .32 | .47 | 0 | 1 | * |

| Covariates | |||||||||

| Age | 43.57 | 11.43 | 22 | 69 | 44.61 | 11.83 | 23 | 68 | |

| Female (vs. male) | .55 | .50 | 0 | 1 | .50 | .50 | 0 | 1 | |

| Childhood financial hardship | 2.72 | .95 | 1 | 5 | 2.42 | .89 | 1 | 5 | *** |

| Parental education | 4.54 | 2.35 | 0 | 11 | 5.69 | 2.81 | 0 | 11 | *** |

| Major life events | 9.55 | 5.22 | 0 | 31 | 8.10 | 5.12 | 0 | 28 | *** |

| Lifetime psychiatric disorders | .53 | .78 | 0 | 4 | .91 | 1.06 | 0 | 5 | *** |

| Married (vs. not married) | .35 | .48 | 0 | 1 | .66 | .47 | 0 | 1 | *** |

| Education (in years) | 13.40 | 2.76 | 0 | 25 | 14.92 | 3.01 | 3 | 28 | *** |

| Financial resources (z-score) | −.34 | .66 | −1.88 | 1.72 | .37 | .82 | −1.58 | 2.19 | *** |

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Unemployed (reference) | .17 | .38 | 0 | 1 | .12 | .33 | 0 | 1 | * |

| Full-time | .61 | .49 | 0 | 1 | .64 | .48 | 0 | 1 | |

| Part-time | .09 | .29 | 0 | 1 | .14 | .35 | 0 | 1 | * |

| Retired | .05 | .22 | 0 | 1 | .05 | .22 | 0 | 1 | |

| Other | .07 | .25 | 0 | 1 | .04 | .20 | 0 | 1 | |

| Obese (vs. not obese) | .58 | .49 | 0 | 1 | .36 | .48 | 0 | 1 | *** |

| Current smoker (vs. former/non-smoker) | .47 | .50 | 0 | 1 | .48 | .50 | 0 | 1 | |

| Heavy drinker (vs. not heavy drinker) | .09 | .29 | 0 | 1 | .09 | .28 | 0 | 1 | |

| Major discrimination | 1.19 | 1.45 | 0 | 7 | .76 | 1.07 | 0 | 6 | *** |

| Daily discrimination | 2.16 | .63 | 1 | 4.78 | 1.93 | .52 | 1 | 4.11 | *** |

| Biomarker Controls | |||||||||

| Takes blood pressure medications | .38 | .48 | 0 | 1 | .22 | .42 | 0 | 1 | *** |

| Did not fast before collection | .03 | .17 | 0 | 1 | .02 | .12 | 0 | 1 | |

| 12-hour urine collection end time | 6:38 | 1:44 | 1:00 | 12:01 | 6:48 | 1:29 | 1:00 | 12:00 | |

| Time of blood collection | 7:55 | 1:58 | 3:32 | 18:50 | 7:58 | 1:46 | 3:13 | 18:27 | |

T-tests and chi-square tests of black-white differences in means/proportions.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 difference between black and white respondents (two-tailed).

Table 2.

Robust linear regression estimates of self-esteem and John Henryism (n=1,252).

| Self-Esteem | John Henryism | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (a) | (b) | |||||||||

| Focal Variables | ||||||||||||

| Black | .180 | (.036) | *** | .100 | (.056) | 1.209 | (.397) | ** | .170 | (.821) | ||

| GSS (scale) | −.014 | (.003) | *** | — | −.097 | (.030) | ** | — | ||||

| Low (reference) | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Middle | — | −.132 | (.053) | * | — | −.658 | (.566) | |||||

| High | — | −.323 | (.070) | *** | — | −2.654 | (.753) | ** | ||||

| Interactions [Black ×…] | ||||||||||||

| GSS (scale) | .011 | (.004) | ** | — | .093 | (.043) | * | — | ||||

| Low (reference) | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Middle | — | .051 | (.076) | — | 1.276 | (1.104) | ||||||

| High | — | .179 | (.083) | * | — | 1.517 | (1.080) | |||||

| Intercept | 4.659 | (.202) | *** | 4.841 | (.211) | *** | 50.330 | (2.041) | *** | 51.438 | (2.172) | *** |

| Adjusted R-squared | .198 | .187 | .094 | .098 | ||||||||

Notes: Unstandardized coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. All estimates adjust for covariates, post-stratification weighting, and clustering at the census block group level. GSS=goal-striving stress. Scaled GSS scores are mean-centered.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed).

Table 5.

Robust linear regression estimates of systolic and diastolic blood pressure (n=1,252).

| Systolic blood pressure | Diastolic blood pressure | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (a) | (b) | |||||||||

| Focal Variables | ||||||||||||

| Black | 3.234 | (1.098) | ** | .138 | (2.029) | 2.020 | (.835) | * | .024 | (1.194) | ||

| GSS (scale) | .041 | (.056) | — | .018 | (.039) | — | ||||||

| Low (reference) | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Middle | — | −1.854 | (1.398) | — | .213 | (.993) | ||||||

| High | — | −.509 | (1.587) | — | .069 | (1.022) | ||||||

| Interactions [Black ×…] | ||||||||||||

| GSS (scale) | −.024 | (.073) | — | .035 | (.054) | — | ||||||

| Low (reference) | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Middle | — | 3.540 | (2.233) | — | 1.953 | (1.601) | ||||||

| High | — | 4.254 | (2.428) | † | — | 3.145 | (1.521) | * | ||||

| Intercept | 115.534 | (4.635) | *** | 116.950 | (4.774) | *** | 78.411 | (3.078) | *** | 78.408 | (3.184) | *** |

| Adjusted R-squared | .234 | .237 | .194 | .196 | ||||||||

Notes: Unstandardized coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. All estimates adjust for covariates, blood pressure medication, fasting, post-stratification weighting, and clustering at the census block group level. GSS=goal-striving stress. Scaled GSS scores are mean-centered.

p<.10,

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed).

For all regression tables, the first set of estimates regressed the outcome variable on scaled GSS scores (mean-centered), race, and their interaction. The second set of estimates then tested for threshold effects of GSS by regressing the outcome on dummy variables of GSS tertiles (low=omitted, middle, high), race, and their interactions. Thus, the GSS coefficients reflect the associations between GSS and the dependent variable for whites, who are the omitted group, while the interaction term coefficients represent the differences in GSS coefficients between blacks and whites. All regression estimates adjusted for covariates, post-stratification weighting, and clustering at the census block group level. I omitted covariate coefficients to conserve space and because the focal variable coefficients were largely unaffected by covariates. I provided complete regression tables before and after adjusting for covariates in the online supplement (Tables S1–S9).

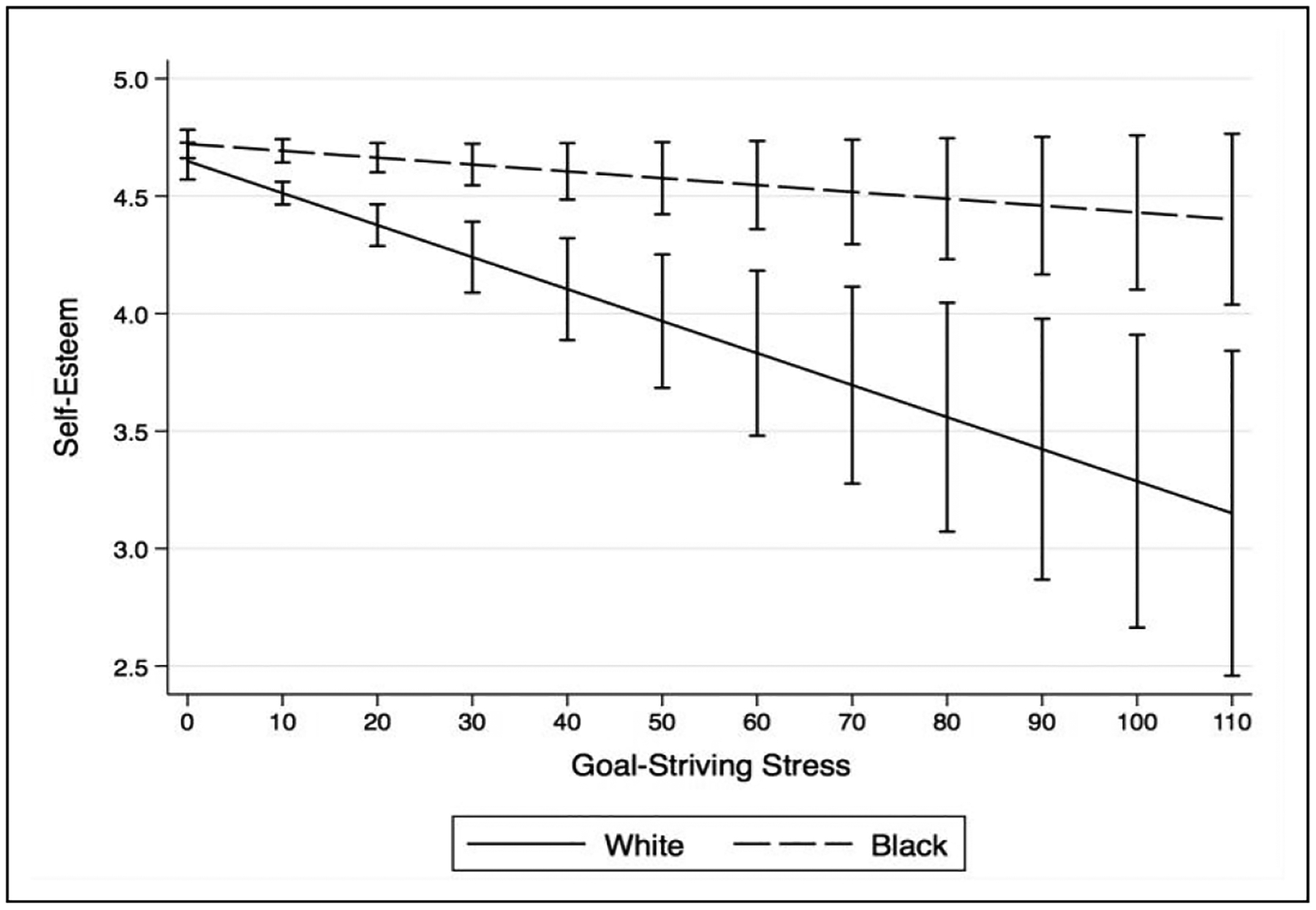

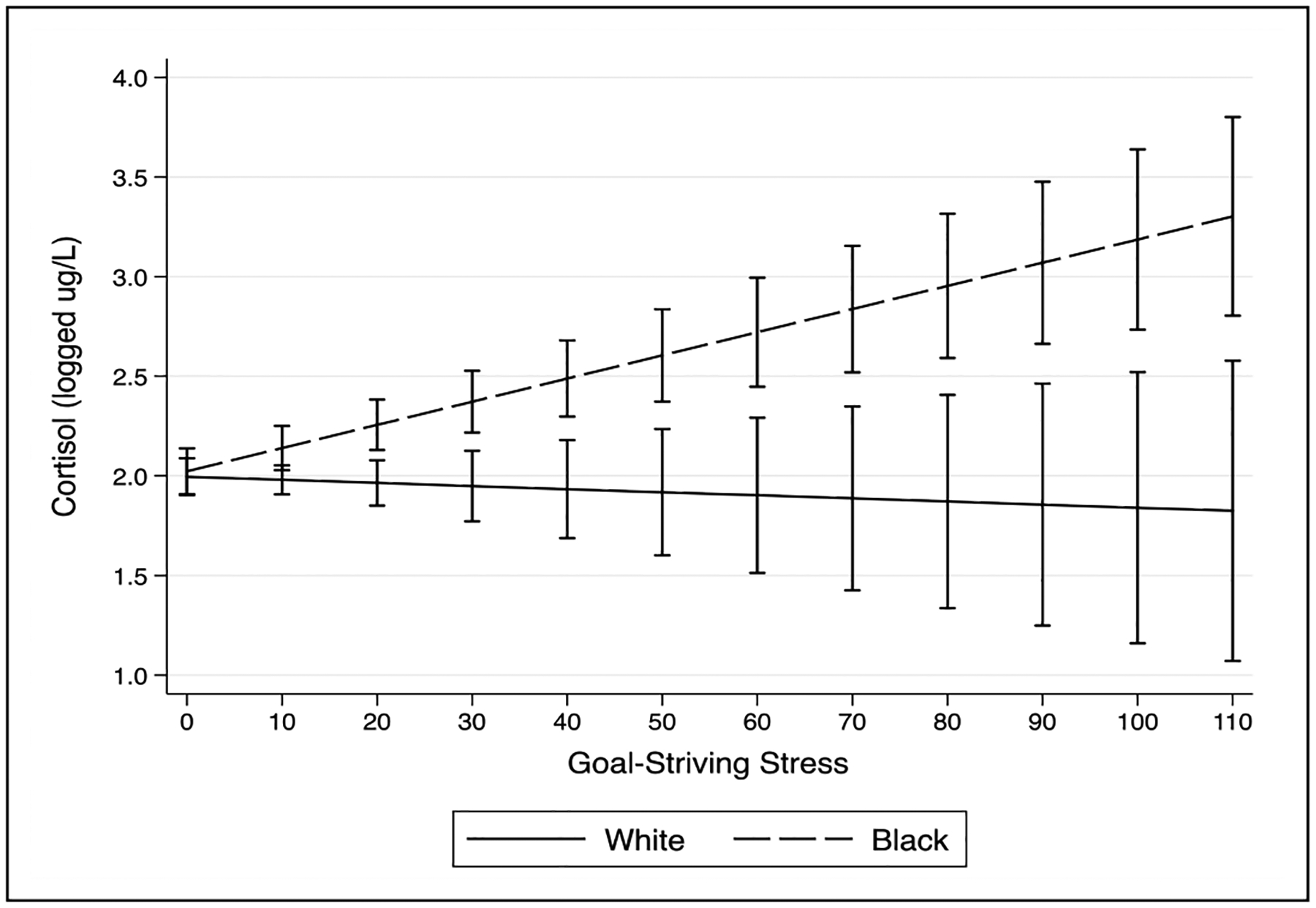

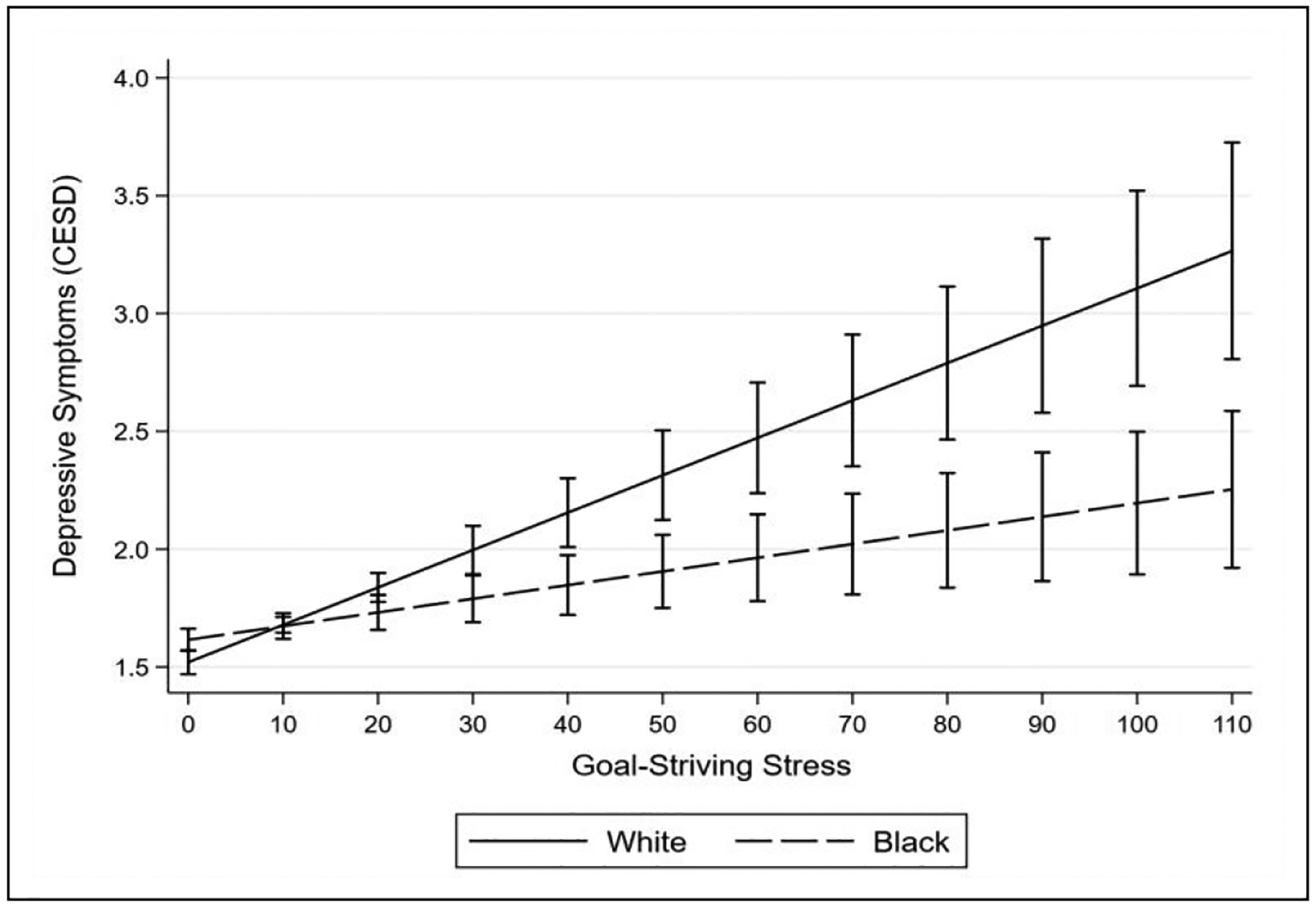

Evidence for my hypotheses will be found if the following conditions are met: (1) GSS coefficients predicting self-esteem and John Henryism are negative while the interaction term coefficients are positive; (2) GSS coefficients predicting depressive symptoms and anxiety are positive while the interaction term coefficients are negative; (3) GSS coefficients predicting cortisol, blood pressure, and cortisol:DHEAS ratio show no association (or are negative) while the interaction term coefficients are positive; and (4) GSS coefficients predicting DHEAS show no association (or are positive) while the interaction term coefficients are negative. To verify that the moderation patterns conformed to my study hypotheses, I also provided visual confirmation of three representative interactions as linear prediction plots with 95% confidence bands (Figures 1–3).

Figure 1.

Self-esteem by race and GSS.

Figure 3.

Cortisol by race and GSS.

Missing data were replaced with 25 iterations of multiple imputation by chained equation (Johnson and Young 2011). The following variables had missing data: self-esteem (n=5), John Henryism (n=3), depressive symptoms (n=9), anxiety (n=1), cortisol (n=93), DHEAS (n=112), systolic/diastolic blood pressure (n=60), childhood financial hardship (n=1), parental education (n=122), major life events (n=51), financial resources (n=44), obesity status (n=38), heavy drinking (n=2), daily discrimination (n=8), fasting before biomarker collection (n=30), blood collection time (n=73), and 12-hour urine collection end time (n=55). The findings reported below were substantively identical before and after imputation. All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 15.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides weighted descriptive statistics of study variables. In terms of psychophysiology, blacks reported higher average levels of self-esteem and John Henryism, but also slightly higher levels of past-month depressive symptoms. Compared to whites, blacks also exhibited lower average levels of DHEAS, higher cortisol:DHEAS ratios, and higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Blacks also reported higher average levels of GSS.

In terms of covariates, blacks tended to report greater childhood financial hardship than whites and had less educated parents, were less educated themselves, and possessed fewer financial resources as adults. Blacks also reported significantly more major life events and discrimination experiences and were more likely to be single, unemployed, obese, and taking blood pressure medications. Consistent with the black-white health paradox, whites still conveyed nearly twice as many lifetime psychiatric disorders than blacks despite blacks expressing greater socioeconomic and physical health disadvantages. Additional descriptive statistics are available below in Table 1.

Table 2 reports unstandardized coefficients from robust linear regression estimates of self-esteem and John Henryism. The results from Table 2 were fully consistent with Hypothesis 1. Higher GSS scores were associated with significantly lower self-esteem and John Henryism among whites, while blacks exhibited essentially no associations between GSS and either outcome. For instance, every one-unit increase in scaled GSS scores predicted a .014-unit decrease in self-esteem for whites (b = −.014; p<.001), but only a .003-unit decrease for blacks (−.014 + .011 = −.003). Figure 1 confirms that the slope predicting change in self-esteem as a function of increasing GSS is essentially flat for blacks but steep and decreasing for whites. The black-white gap in GSS slopes predicting self-esteem also reached two-tailed significance at the p<.01 threshold. This moderation pattern also looked more-or-less identical when predicting John Henryism. There was also evidence of a threshold effect of GSS on self-esteem. To be specific, blacks in the high (vs. low) GSS category reported significantly higher self-esteem than their white counterparts.

Table 3 also provides consistent support for Hypothesis 1. For instance, a one-unit increase in GSS predicted a .016–unit increase in depressive symptoms for whites (b = .016; p<.001), whereas the same increase in GSS predicted only a .006–unit increase in depressive symptoms for blacks (.016 − .010 = .006). Figure 2 provides visual confirmation of this moderation pattern. The same patterns surfaced for anxiety. Black-white differences in slopes predicting depressive symptoms and anxiety as a function of GSS also reached two-tailed significance at the p<.001 threshold. There was also evidence of threshold effects of GSS, with blacks in the high (vs. low) category of GSS reporting significantly fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety than their white counterparts.

Table 3.

Robust linear regression estimates of depressive symptoms and anxiety (n=1,252).

| Depressive Symptoms | Anxiety | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (a) | (b) | |||||||||

| Focal Variables | ||||||||||||

| Black | −.007 | (.034) | .066 | (.048) | −.103 | (.050) | * | .075 | (.075) | |||

| GSS (scale) | .016 | (.002) | *** | — | .019 | (.003) | *** | — | ||||

| Low (reference) | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Middle | — | .143 | (.040) | *** | — | .255 | (.055) | *** | ||||

| High | — | .362 | (.053) | *** | — | .460 | (.069) | *** | ||||

| Interactions [Black ×…] | ||||||||||||

| GSS (scale) | −.010 | (.002) | *** | — | −.013 | (.003) | *** | — | ||||

| Low (reference) | — | — | — | — | ||||||||

| Middle | — | −.074 | (.062) | — | −.195 | (.100) | ||||||

| High | — | −.135 | (.065) | * | — | −.288 | (.107) | ** | ||||

| Intercept | 1.012 | (.143) | *** | .816 | (.150) | *** | .997 | (.217) | *** | .702 | (.220) | ** |

| Adjusted R-squared | .448 | .428 | .334 | .322 | ||||||||

Notes: Unstandardized coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. All estimates adjust for covariates, post-stratification weighting, and clustering at the census block group level. GSS=goal-striving stress. Scaled GSS scores are mean-centered.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed).

Figure 2.

Depressive symptoms by race and GSS.

Table 4 reports coefficients for HPA axis biomarkers. The coefficients in this table provided consistent support for Hypothesis 2. For example, a one-unit increase in GSS predicted a .011-unit increase in logged cortisol levels for blacks (.013 – .002 = .011), whereas GSS was not associated with cortisol for whites. This pattern can be seen clearly in Figure 3. Blacks in the middle and high (vs. low) GSS categories also reported significantly lower logged DHEAS levels than their white counterparts. GSS also predicted significantly higher cortisol:DHEAS ratios for blacks but no difference for whites.

Table 4.

Robust linear regression estimates of HPA axis biomarkers (n=1,252).

| Cortisol | DHEAS | Cortisol:DHEAS ratio | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (a) | (b) | (a) | (b) | |||||||||||||

| Focal Variables | ||||||||||||||||||

| Black | .159 | (.076) | * | −.085 | (.141) | −.170 | (.044) | *** | −.021 | (.069) | .332 | (.077) | *** | −.051 | (.150) | |||

| GSS (scale) | −.002 | (.004) | .000 | (.002) | — | −.001 | (.004) | — | ||||||||||

| Low (reference) | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||||

| Middle | — | −.014 | (.085) | — | .028 | (.066) | — | −.036 | (.112) | |||||||||

| High | — | .027 | (.093) | — | −.024 | (.076) | — | .052 | (.123) | |||||||||

| Interactions [Black ×…] | ||||||||||||||||||

| GSS (scale) | .013 | (.004) | ** | −.002 | (.003) | — | .015 | (.005) | ** | — | ||||||||

| Low (reference) | — | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||||

| Middle | — | .256 | (.164) | — | −.197 | (.097) | * | — | .434 | (.167) | * | |||||||

| High | — | .379 | (.129) | ** | — | −.179 | (.089) | * | — | .552 | (.171) | ** | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.916 | (.307) | *** | 1.924 | (304) | *** | 6.083 | (.270) | *** | 6.064 | (.292) | *** | −4.254 | (.376) | *** | −4.232 | (.395) | *** |

| Adjusted R-squared | .096 | .097 | .403 | .405 | .154 | .160 | ||||||||||||

Notes: Unstandardized coefficients are reported with robust standard errors in parentheses. All estimates adjust for covariates, biomarker controls, post-stratification weighting, and clustering at the census block group level. Cortisol, DHEAS, and cortisol:DHEAS ratio are in natural logarithmic form. GSS=goal-striving stress. Scaled GSS scores are mean-centered.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 (two-tailed).

To place these findings in more concrete terms, I examined exponentiated marginal predictions of average cortisol, DHEAS, and cortisol:DHEAS ratio levels by race and GSS grouping. I provided a table of these values in the online appendix (Table S11). The following patterns emerged for blacks as they moved from the low to high GSS group: (1) cortisol levels rose from 6.63 ug/L to 9.96 ug/L (50% increase), (2) serum DHEAS levels diminished from 116.58 ug/dL to 95.47 ug/dL (18% decrease), and (3) cortisol:DHEAS ratios rose from .06 to .10 (67% increase). Whites, on the other hand, exhibited the following patterns as they moved from low to high GSS: (1) cortisol levels barely rose from 7.22 ug/L to 7.42 ug/L (< 3% increase), (2) DHEAS levels declined only slightly from 120.09 ug/dL to 117.88 ug/dL (< 2% decrease), and (3) ratios of cortisol to DHEAS remained stable at .06.2

Table 5 shows similar patterns for systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Blacks in the high (vs. low) GSS category presented average systolic blood pressure readings that were 4.25 mmHg higher than their white counterparts. However, this difference in averages only reached one-tailed significance (t = 1.75). High-GSS blacks also had significantly higher average diastolic blood pressure readings than high-GSS whites (b = 3.145; p<.05).

Finally, it is worth noting that there were no black-white differences in psychophysiology when GSS was low. This can be seen by examining the black coefficients in all the (b) estimates, which represent predicted black-white differences in each outcome for respondents who scored in the bottom tertile of the GSS distribution. This finding indicates that black-white disparities in psychophysiology emerged only as both groups began to confront increasing levels of GSS.

DISCUSSION

My analyses revealed substantial black-white differences in the associations between GSS and psychophysiology. For blacks, GSS was associated with little to no differences in self-esteem, high-effort coping, or psychological distress, but significant increases in blood pressure and cortisol and decreases in DHEAS (a cortisol antagonist). For whites, however, GSS was associated with considerably lower levels of self-esteem and high-effort coping and higher levels of psychological distress, but no differences in blood pressure, cortisol, or DHEAS. These patterns were also robust to different model specifications and adjustments for numerous covariates.

My study makes several key contributions to our understanding of the stress process and black-white health inequalities in the United States. First, I advance stress process research by refocusing attention on a neglected class of stressors: anticipatory stressors. Anticipatory stressors are distinct from acute stressors and chronic strains because they do not exist as concrete realities but can affect people just the same (Pearlin and Bierman 2013). This is because human beings have evolved advanced brain structures capable of drawing complex inferences about potential futures from past experiences (Massey 2001; Barrett 2017). Consequently, our mental images of anticipated stressors (e.g., failing to achieve a major life goal) can trigger physiological responses similar to those that occur when our bodies are adapting to existing stressors (e.g., discriminatory treatment). In many ways, then, anticipatory stressors can be more enduring and pernicious than existing stressors given that no direct environmental stimulus is needed to trigger a stress response (Sapolksy 1998; O’Donovan et al. 2012). In the analyses reported here, GSS remained a robust predictor of psychophysiology even after accounting for objective socioeconomic conditions and various other prior and existing stressors.

The current study also highlights the GSS scale as an important but underutilized survey measure of anticipatory stress. The theoretical roots of GSS stretch back to the origins of sociology when Durkheim ([1897] 1951) offered the first systematic analysis of social structure and anomie. In keeping with Merton’s (1938, 1968) retooling of anomie theory, Parker and Kleiner (1966) developed the GSS scale to observe the individual-level consequences of structural anomie, particularly among black Americans striving for upward mobility during the civil rights era. In their original analysis of GSS among blacks in Philadelphia, Parker and Kleiner hypothesized that blacks in their study would internalize experiences with failure and suffer “severe loss of self-esteem” and poor mental health (Parker and Kleiner 1966: 12). What they discovered, instead, was that the links between GSS and psychological functioning for blacks were highly complex and defied simple explanation.

The second contribution of my study is that I draw from more recent scholarship on the racial socialization of black and white Americans to show that experiences with GSS can be quite distinct across racial groups. What Parker and Kleiner’s (1966) early work in this area did not account for is that blacks might experience GSS in fundamentally different ways than whites. For example, the authors proposed the following rationale for studying GSS among blacks:

Like his fellow Americans, the Negro internalizes the common success values and assumes…that his chances of achieving his aspirations are good…He, too, is led to believe in the ethos of the open social system which permits a high rate of social mobility. Given the objective fact of the limited opportunity structure for the Negro, this estimate of reality is not feasible and frequently leads to frustration (Parker and Kleiner 1966: 12).

My findings suggest, instead, that blacks are well aware they must “work twice as hard to get half as much.” Indeed, many blacks learn from a young age not to attribute their setbacks and failures to personal incompetence, but rather to identify racist sociopolitical structures as central causes of their struggles (Coard and Sellers 2008; Bentley et al. 2008; Sellers et al. 2012). Still, my findings imply that this awareness functions as a double-edged sword for black Americans. The unrelenting specter of racialized barriers to attainment places a heavy burden on blacks of always having to be prepared to overcome barriers with extreme effort (James 1994). As my analyses revealed, blacks with increasing GSS still expressed high and unwavering levels of John Henryism, a self-reported index of persistent and high-effort coping in the face of overwhelming barriers to success.

The third contribution of my study is to demonstrate that proactive coping and psychosocial resilience can sometimes pair with physiological dysfunction. In my analyses, blacks with high GSS also exhibited elevated blood pressure and HPA axis activity. This finding dovetails with an emerging literature on the “skin-deep resilience” of upwardly mobile black Americans. Studies in this field have found that ambitious and upwardly mobile blacks from disadvantaged backgrounds tend to express remarkable psychosocial resilience even as they show signs of physiological deterioration. An intriguing hypothesis in this area is that high-effort coping with barriers to mobility are responsible for these associations (see Gaydosh et al. 2018). By explicitly linking GSS to John Henryism in addition to stress biomarkers, my study offers compelling evidence in support of the high-effort coping hypothesis.

Why should proactive coping with strained goals lead to physiological wear-and-tear for black Americans? At first glance, this finding seems to fly in the face of conventional wisdom regarding stress adaptation. In his now classic formulation of allostatic load theory, for example, McEwen (1998: 37) contends that physiological stress responses are

closely coupled to the psychological make-up of the individual, in that those people who are fearful and reactive will have more reactive physiological responses, whereas those individuals who have proactive planning skills and psychological buffers will have less reactive responses and more stability in their physiology.

According to this logic, we should have expected whites with high GSS to also exhibit higher levels of cortisol and blood pressure relative to their black peers.

This paradox resolves itself after acknowledging that the same stressor can entail drastically different meanings and experiences for different groups of people (McLeod 2012). I suggested earlier that racial differences in experiences with GSS can be attributed to the dissimilar social contexts in which blacks and whites must contend with barriers to their goals. Because opportunity structures in the United States have been systematically engineered to thwart blacks (Rothstein 2017), whites enjoy cumulative advantages over blacks that can help them recover quicker from thwarted goals at all stages of the life course (Malat et al. 2017). Blacks, on the other hand, can never fully outrun prospects of discrimination and failure regardless of their achieved statuses or material resources (Feagin and Sikes 1994; Turner et al. 2017). For blacks, then, the anticipation of failure seems to represent a chronic looming threat that demands constant mental acuity and physiological adaptation. For whites, however, prospects of failure appear to be psychologically distressing but nonetheless transitory experiences that ultimately do not require much physiological adaptation.

The very act of maintaining unflinching self-control and positive emotions in the face of strained goals could also be creating added physiological burdens for blacks. Experimental studies have found that people who express stoic levels of emotional restraint and self-control often do report better mental health, yet they also tend to exhibit overactive physiological stress responses as indexed by higher cortisol and blood pressure (Sapolsky 1998: 283–286; see also Stefen et al. 2003; Dorr et al. 2007). A key takeaway from this literature is that blacks who always “stay with it” and refuse to “let feelings get in the way” of strained goals could be suffering an extra physiological burden of constantly having to monitor themselves to combat negative emotions and behaviors deemed to be self-defeating or counterproductive (e.g., Lambert, Robinson, and Ialongo 2014).

The findings from my study could have broader implications for black-white health inequalities in the United States. For one, blacks are more likely than whites to die prematurely from chronic health conditions such as heart disease, kidney disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes (Hummer and Hamilton 2019: 133–137). A recent study has found that old-age blacks also tend to display blunted cortisol responses relative to their white peers, which is another indication of physiological dysregulation due to lifelong stress exposure (Allen et al. 2019). The current study suggests that prolonged coping with barriers to attainment during working-age years may help explain why black Americans suffer early morbidity and mortality, as such high-effort coping appears to strain the HPA axis and cardiovascular system. Indeed, studies have shown that HPA axis dysregulation and elevated blood pressure can lead to the very same chronic conditions mentioned above (Sapolsky 1998; Goosby et al. 2018).

GSS may also be implicated in the apparent rise in “deaths of despair” among white Americans (Case and Deaton 2015). Historically, dominant success narratives in the United States have cast working- and middle-class whites as the main protagonists and beneficiaries of the American Dream (Hochschild 1995: 26). Because generations of white Americans have grown accustomed to the perquisites of living in a white supremacist society, many whites are woefully unequipped to cope with economic crises or any other circumstance that undermines their relative social standing (e.g., Kraus et al. 2012), and thus tend to be exceptionally vulnerable to mental illness whenever such circumstances do occur (Malat et al. 2017). My study suggests that GSS can be a useful way to conceptualize and measure the psychosocial strains experienced by downwardly mobile white populations. For many white Americans, the realization that their dreams are at the throes of powerful external forces may shatter their faith in meritocracy and lead to profound feelings of normlessness and despair.

The current study has limitations that could be overcome in the future. One limitation is that I analyzed cross-sectional data from a single urban locale rather than longitudinal data from a nationally representative cohort. I therefore cannot establish temporal ordering between variables or rule out the possibility that there is something unique about the black and white working-age adult population of Nashville. Notwithstanding, the NSAHS provided an unusually rich collection of self-report and biological data from a reasonably large probability sample of adults, which would have been onerous and costly to collect on a national and long-term scale. The findings generated in my study were also consistent with longstanding sociological theories and nationally observed patterns, and were robust to various model specifications and adjustments for numerous covariates. I can therefore see little reason to believe my findings were spurious or somehow idiosyncratic to Nashville.

Despite some limitations, my study advances our understanding of the stress process and black-white health disparities in the United States. First, I help reinvigorate discussion of anticipatory stressors and demonstrate that the GSS scale is useful for measuring this unique class of stressors. Second, I develop and test hypotheses to explain why experiences with GSS should be markedly different for black and white Americans. Third, I provide evidence that black-white differences in coping with GSS lead to distinct psychophysiological outcomes that are consistent with the broader black-white health paradox. My hope is that the current study sparks continued interdisciplinary research aimed at addressing these urgent population health dilemmas.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks Bob Hummer for providing helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

FUNDING

The author is grateful to the Carolina Population Center and its NIH center grant (T32-HD091058) for general support.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Reed DeAngelis is a doctoral student in sociology at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and a biosocial predoctoral trainee at the Carolina Population Center. His research is focused on social stratification and health in the United States with an emphasis on stress and coping. His current projects highlight religious involvement, racial and gendered self-perceptions, and family ties as important social determinants of health. Reed is currently supported by the National Institutes of Health and has published his research in Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Society and Mental Health, Sleep Health, Population Research and Policy Review, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, and Journal of Religion and Health, among other outlets.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

The majority of these respondents anchored their current status only one or two rungs beneath the top.

It is worth noting that the adjusted R-squared values for DHEAS were noticeably higher than those for cortisol and blood pressure. This is because DHEAS levels tend to be more closely linked to chronological age, with levels steadily declining over the life course (Lane et al. 1997). Respondent age accounted for 13% of unique variance in serum DHEAS levels among the NSAHS sample.

REFERENCES

- Agnew Robert. 1997. “The Nature and Determinants of Strain: Another Look at Durkheim and Merton” Pp. 27–51 in The Future of Anomie Theory. Boston: Northeastern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen Julie O., Watkins Daphne C., Chatters Linda, Geronimus Arline T., and Johnson-Lawrence Vicki. 2019. “Cortisol and Racial Health Disparities Affecting Black Men in Later Life: Evidence from MIDUS II.” American Journal of Men’s Health 13(4): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson Matthew A. 2015. “How Do We Assign Ourselves Social Status? A Cross-Cultural Test of the Cognitive Averaging Principle.” Social Science Research 52: 317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin Oscar A. 1993. “Coping and Resilience: Exploring the Inner Lives of African American Children.” Journal of Black Psychology 19(4): 478–492. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett Lisa F. 2017. How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley Keisha L., Adams Valerie N., and Stevenson Howard C.. 2008. “Racial Socialization: Roots, Processes, and Outcomes” Pp. 255–267 in Handbook of African American Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bobo Lawrence, Kluegel James R., and Smith Ryan A.. 1997. “Laissez-faire Racism: The Crystallization of a ‘Kindler, Gentler’ Anti-black Ideology” Pp. 15–42 in Racial Attitudes in the 1990s: Continuity and Change. Westport, CT: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva Eduardo. 2017. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 5th edition Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Danice L. 2008. “African American Resiliency: Examining Racial Socialization and Social Support as Protective Factors.” Journal of Black Psychology 34(1): 32–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cain Loretta R., Glover LáShauntá, Young Bessie, and Sims Mario. 2019. “Goal-Striving Stress Is Associated with Chronic Kidney Disease Among Participants in the Jackson Heart Study.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 6(1): 64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantril Hadley. 1965. The Pattern of Human Concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP. [Google Scholar]

- Case Anne, and Deaton Angus. 2015. “Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(49):15078–15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coard Stephanie I., and Sellers Robert M.. 2005. “African American Families as a Context for Racial Socialization” Pp. 264–284 In African American Family Life: Ecological and Cultural Diversity. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daly Alfriede, Jennings Jeanette, Beckett Joyce O., and Leashore Bogart R.. 1995. “Effective Coping Strategies of African Americans.” Social Work 40(2): 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis Reed T. 2018. “Goal-Striving Stress and Self-Concept: The Moderating Role of Perceived Divine Control.” Society and Mental Health 8(2):141–56. [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis Reed T., and Ellison Christopher G.. 2018. “Aspiration Strain and Mental Health: The Education-Contingent Role of Religion.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57(2):341–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dorr Nancy, Brosschot Jos F., Sollers John J., and Thayer Julian F.. 2007. “Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t: The Differential Effect of Expression and Inhibition of Anger on Cardiovascular Recovery in Black and White Males.” International Journal of Psychophysiology 66(2):125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois WEB 1899. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim Emile. [1897] 1951. Suicide. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy Pennie, Wertheim Eleanor H., Hale Matthew W., and Wright Bradley J.. 2018. “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effort-Reward Imbalance Model of Workplace Stress and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Measures of Stress:” Psychosomatic Medicine 80(1):103–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin Joe R. 1975. Subordinating the Poor: Welfare and American Beliefs. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin Joe R., and Sikes Melvin P.. 1994. Living with Racism: The Black Middle-class Experience. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Ann R., and Shaw Christina M.. 1999. “African Americans’ Mental Health and Perceptions of Racist Discrimination: The Moderating Effects of Racial Socialization Experiences and Self-Esteem.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 46(3):395–407. [Google Scholar]

- Gaydosh Lauren, Schorpp Kristen M., Chen Edith, Miller Gregory E., and Harris Kathleen Mullan. 2018. “College Completion Predicts Lower Depression but Higher Metabolic Syndrome among Disadvantaged Minorities in Young Adulthood.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(1):109–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby Bridget J., Cheadle Jacob E., and Mitchell Colter. 2018. “Stress-related Biosocial Mechanisms of Discrimination and African American Health Inequities.” Annual Review of Sociology 44: 319–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicken Margaret T., Lee Hedwig, and Hing Anna K.. 2018. “The Weight of Racism: Vigilance and Racial Inequalities in Weight-Related Measures.” Social Science & Medicine 199:157–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild Jennifer L. 1995. Facing up to the American Dream: Race, Class, and the Soul of the Nation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer Robert A., and Hamilton Erin R.. 2019. Population Health in America. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- James Sherman A. 1994. “John Henryism and the Health of African-Americans.” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 18(2):163–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson David R., and Young Rebekah. 2011. “Toward Best Practices in Analyzing Datasets with Missing Data: Comparisons and Recommendations.” Journal of Marriage and Family 73(5):926–45. [Google Scholar]

- Kamin Hayley S. and Kertes Darlene A.. 2017. “Cortisol and DHEA in Development and Psychopathology.” Hormones and Behavior 89:69–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C. 1979. “Stress, Social Status, and Psychological Distress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 20(3):259–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler Ronald C., Mickelson Kristin D., and Williams David R.. 1999. “The Prevalence, Distribution, and Mental Health Correlates of Perceived Discrimination in the United States.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 40: 208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus Michael W., Piff Paul K., Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton Michelle L. Rheinschmidt, and Keltner Dacher. 2012. “Social Class, Solipsism, and Contextualism: How the Rich are Different from the Poor.” Psychological Review 119(3):546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert Sharon F., Robinson W. LaVome, and Ialongo Nichols S.. 2014. “The Role of Socially Prescribed Perfectionism in the Link between Perceived Racial Discrimination and African American Adolescents’ Depressive Symptoms.” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 42(4):577–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane Mark A., Ingram Donald K., Ball Sheldon S., and Roth George S.. 1997. “Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate: A Biomarker of Primate Aging Slowed by Calorie Restriction.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 82(7): 2093–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd Donald A., and Turner R. Jay. 2008. “Cumulative Lifetime Adversities and Alcohol Dependence in Adolescence and Younger Adulthood.” Journal of Alcohol and Drug Dependence 93(3):217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie Patricia, and Wheaton Blair. 2019. “The Black-White Paradox Revisited: Understanding the Role of Counterbalancing Mechanisms during Adolescence.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 60(2):169–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malat Jennifer, Mayorga-Gallo Sarah, and Williams David R.. 2018. “The Effects of Whiteness on the Health of Whites in the USA.” Social Science & Medicine 199: 148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. 2001. “A Brief History of Human Society: The Origin and Role of Emotion in Social Life.” American Sociological Review 67(1): 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Marteau Theresa M., and Bekker Hilary. 1992. “The Development of a Six-Item Short-Form of the State Scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).” British Journal of Clinical Psychology 31(3):301–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen Bruce S. 1998. “Stress, Adaptation, and Disease: Allostasis and Allostatic Load.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 840(1):33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod Jane D. 2012. “The Meanings of Stress: Expanding the Stress Process Model.” Society and Mental Health 2(3):172–186. [Google Scholar]

- McNamee Stephen J., and Miller Robert K.. 2014. The Meritocracy Myth. 3rd edition Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Merton Robert K. 1938. “Social Structure and Anomie.” American Sociological Review 3(5):672–82. [Google Scholar]

- —1968. Social Theory and Social Structure. 3rd edition New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Messner Steven F., and Rosenfeld Richard. 2001. Crime and the American Dream. 3rd edition Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

- Metzl Jonathan M. 2019. Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland. London: Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors Harold W., Sellers Sherrill L., Zhang Rong, and Jackson James S.. 2011. “Goal-Striving Stress and Racial Differences in Mental Health.” Race and Social Problems 3(1):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan Aoife, Tomiyama A. Janet, Lin Jue, Puterman Eli, Adler Nancy E., Kemeny Margaret, Wolkowitz Owen M., Blackburn Elizabeth H., and Epel Elissa S.. 2012. “Stress Appraisals and Cellular Aging: A Key Role for Anticipatory Threat in the Relationship between Psychological Stress and Telomere Length.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 26(4):573–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker Seymour, and Kleiner Robert J.. 1966. Mental Illness in the Urban Negro Community. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I., and Bierman Alex. 2013. “Current Issues and Future Directions in Research into the Stress Process” Pp. 325–340 In Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I., Menaghan Elizabeth G., Lieberman Morton A., and Mullan Joseph T.. 1981. “The Stress Process.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22(4):337–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin Leonard I. and Schooler Carmi. 1978. “The Structure of Coping.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19(1):2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff Lenore S. 1977. “The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population.” Applied Psychological Measurement 1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg Morris. 1965. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. New Jersey: Princeton UP. [Google Scholar]

- — 1986. Conceiving the Self. Malabar: Krieger. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein Richard. 2017. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing. [Google Scholar]