Abstract

Human T-cell leukemia virus type-1 (HTLV-1) encodes a mitochondrial protein named p13. p13 mediates an inward K+ current in isolated mitochondria that leads to mitochondrial swelling, depolarization, increased respiratory chain activity and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. These effects trigger the opening of the permeability transition pore and are dependent on the presence of K+ and on the amphipathic alpha helical domain of p13. In the context of cells, p13 acts as a sensitizer to selected apoptotic stimuli. Although it is not known whether p13 influences the activity of endogenous K+ channels or forms a channel itself, it shares some structural and functional analogies with viroporins, a class of small integral membrane proteins that form pores and alter membrane permeability.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Potassium channel, HTLV-1, Viroporin, Calcium homeostasis, Apoptosis, Leukemia

1. Introduction

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infects about 15–25 million people worldwide, with high prevalence in southwestern Japan, central Africa and the Caribbean basin. While most infected individuals remain asymptomatic, about 3% eventually develop an aggressive neoplasm of mature CD4+ cells termed adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) that arises after several decades of infection. HTLV-1 also causes a neurological disease termed tropical spastic paraparesis/HTLV-associated myelopathy (TSP/HAM), a progressive demyelinating disease; similar to ATLL, TSP/HAM arises in about 3% of infected individuals, but after a latency period of years rather than decades [1].

The 3′ portion of the HTLV-1 genome (termed the X region) contains at least four open reading frames (ORFs x-I, II, III and IV) that code for non-structural regulatory proteins. Expression of these partially overlapping ORFs is accessed through alternative splicing and multicistronic translation. Proteins coded in the X region play key roles in the control of viral gene expression and host cell turnover [2]. The ability of HTLV-1 to immortalize T-cells is attributable primarily to the X-region protein Tax, which, in addition to transactivating the viral promoter, affects the expression and function of cellular genes controlling signal transduction, cell growth, apoptosis and chromosomal stability [1].

2. Amino acid sequence and structural features of HTLV-1 p13

The present review focuses on p13, an 87-amino acid mitochondrial protein coded by the HTLV-1 x-II ORF from a singly spliced mRNA [2], [3], [4]. Fig. 1 shows the amino acid sequence (Panel A) and in silico analysis of p13’s structure (Panel B, ProtScale software, [5]) indicating that the N-terminus of the protein includes an amphipathic α-helix (residues 20–35) and a transmembrane region (residues 30–40). These predictions are supported by circular dichroism analysis of a synthetic peptide corresponding to residues 9–41 (p139–41) which folds into an α-helix when exposed to membrane-like environments (e.g. SDS and lipid vesicles) [6]. Interestingly, this region contains the mitochondrial targeting signal of p13 and is essential for its function (see below; [7]). Biochemical fractionation studies showed that p13 is indeed inserted as integral membrane protein in the inner mitochondrial membrane (see below; [6]). The high flexibility score of the PPTSSRP motif (residues 42–48) suggests that this might represent a hinge region. The C-terminal region (residues 65–75) is predicted to fold as a β-sheet structure. This region includes the sequence WTRYQLSSTVPYPS, which is highly homologous to the synthetic peptide WRYYESSLEPYPD that has been described to bind with high affinity to α-bungarotoxin, a snake-venom neurotoxin that inhibits the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) at the neuromuscular junction [8]. Binding of the WRYYESSLEPYPD peptide to the toxin inhibits the latter’s ability to interact with AChR. NMR spectroscopy showed that the bound peptide folds into a β-hairpin structure formed by two antiparallel β-strands, which combine with a triple-stranded β-sheet of the toxin to form a five-stranded, antiparallel β-sheet structure. The sequence similarity between this peptide and residues 65–75 of p13 suggests that the latter might represent an important protein–protein interaction domain. Finally, the C-terminal tail of p13 is characterized by several PXXP motifs that might mediate binding of p13 to proteins containing SH3 domains. Results of experimental data described in Ref. [6] and the in silico predictions were integrated to construct a hypothetical model of p13 structure in the context of the inner mitochondrial membrane, shown in Fig. 1C.

Fig. 1.

p13 sequence and predicted structure. Panel A shows the amino acid sequence of p13 with the mitochondrial targeting signal underlined. Panel B shows in silico analysis of p13’s structure using the ProtScale Software provided by the ExPASy Proteomics Server; graphs show the predicted scores for α-helix (Deleage & Roux), the transmembrane tendency, average flexibility, and total beta strand of the different regions of the protein. Panel C shows a hypothetical model of p13’s structure in the context of the inner mitochondrial membrane based on results of experimental data described in Ref. [6] and in silico predictions shown in Panel B. Segments A–D of the protein represent, respectively, the amphipathic α-helical domain, the transmembrane domain, the hinge region and the C-terminal beta sheet hairpin. Panel C also shows a more detailed helical wheel model of the amphipathic α-helical domain of p13 (amino acids 20–35). Panel C does not indicate the matrix and intermembrane space faces of the inner membrane, as the topology of p13 has not been defined.

3. Intracellular localization of p13

Initially p13 was reported to localize to the nucleus [9], although subsequent studies showed that the protein is mainly targeted to mitochondria [7], with partial nuclear targeting observed only at higher expression levels. Immuno-electron microscopy and sub-mitochondrial fractionation experiments demonstrated that the majority of p13 is inserted as an integral membrane protein in the inner mitochondrial membrane [6]. The mitochondrial targeting of p13 is directed by an atypical mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS) formed by 10 amino-proximal residues (amino acids 21–30) that are contained within the α-helix described above [7], with four arginines in the MTS conferring amphipathic properties to the helix. In contrast to canonic MTSs, the targeting signal of p13 is not cleaved upon import into mitochondria [7]. More recently Ghorbel et al. [10] described a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) at the C-terminus of p13. The authors suggest that this NLS may target p13 to the nucleus in conditions in which the MTS is masked.

4. Effects of p13 on mitochondria

In the context of cells, p13 expression was shown to induce mitochondrial fragmentation [7]. This effect is dependent on the presence of positively charged amino acids in the MTS. Interestingly, these residues are not essential for mitochondrial targeting of p13 [6], suggesting that the mitochondrial targeting and mitochondrial-fragmenting functions mediated by the amphipathic α-helix might be somewhat distinct. To define the mechanism of function of p13 at the mitochondrial level, we carried out experiments using isolated rat liver mitochondria and synthetic p13. Assays were carried out in isotonic K+ buffer and mitochondria were energized with glutamate and malate. In these experimental conditions p13 induced osmotic swelling of mitochondria measured as 90° light scattering at 540 nm. Using a rhodamine 123 dequenching assay we also showed that p13 alters inner mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ). This effect is tightly linked to the ability of the protein to change K+ permeability, as mutants unable to induce K+-dependent swelling also did not influence Δψ. Similar results were obtained with the shorter p13 peptide (p139–41) [6], although the full-length protein is about 10-fold more potent than p139–41. The effects induced by p13 are dose-dependent, and at low p13 concentrations swelling is reverted by mitochondrial depolarization (e.g. by using protonophores). “Reversible” swelling induced by low doses of p13 is not accompanied by mitochondrial depolarization or cytochrome c release; in contrast, higher concentrations of p13 induce irreversible swelling, depolarization and cytochrome c release from isolated mitochondria [11]. p13 induces a shape change in mitochondria, which acquire a crescent-like morphology that is distinct from that resulting from large-amplitude swelling triggered by opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP), a large conductance mitochondrial channel controlling cytochrome c release and apoptosis [11]. Interestingly, these shape changes are evident at low doses of p13 (e.g. 50 nM) and are is reverted by depolarization induced by protonophores, suggesting that the basis for this change is directly linked to energy-dependent K+ influx. Irreversible swelling triggered by high doses of p13 results in a change in mitochondrial morphology that resembles that induced by PTP opening (i.e. large-amplitude swelling with loss of internal electron-dense structure).

The effects of p13 on mitochondrial respiration were tested by polarographic measurements of O2 consumption with a Clark oxygen electrode. Results showed that p13 triggers a dose-dependent increase in mitochondrial respiration; interestingly, this change, by extruding H+ from the matrix, maintains Δψ at least within a low concentration range of p13 [11]. These changes lead to increased mitochondrial ROS production, which was measured using the fluorescent H2O2 probe Amplex UltraRed in the presence of horseradish peroxidase [11]. The Increased ROS production and depolarization induced by p13 in turn lower the opening threshold of the PTP [11], which was assessed using the calcium retention capacity assay based on the Ca2+ fluorescent probe Calcium Green-5N [12].

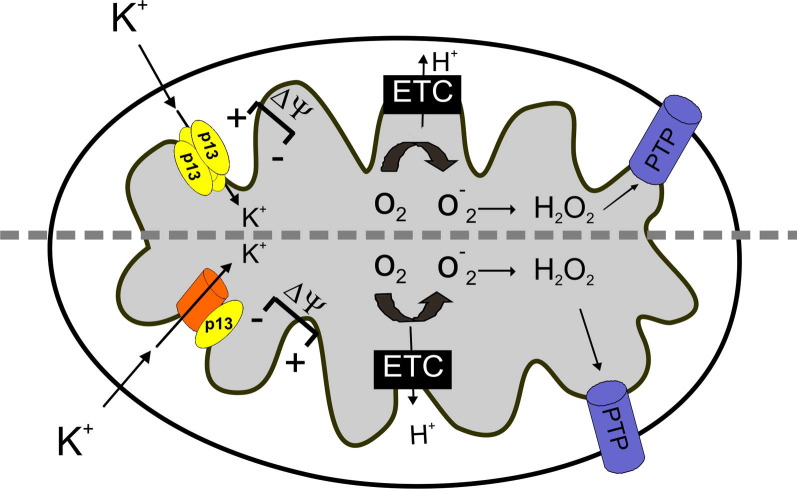

One of the questions left unanswered by the studies carried out thus far is whether the effects of p13 on mitochondrial permeability result from its interaction with an endogenous mitochondrial channel [13] or, in alternative, if p13 exhibits intrinsic channel-forming activity (Fig. 2 ). Searches for binding partners of p13 based on yeast 2-hybrid screens and pull-down assays indicate that p13 binds to a protein of the nucleoside monophosphate kinase superfamily, actin-binding protein 280, and farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase [14], [15], none of which would be expected to form part of a K+ channel. On the other hand, p13 displays several properties that indicate that it might form channels itself, including its insertion into membranes, the presence of the amphipathic α-helix and a transmembrane domain mentioned above and its propensity to form high-order, SDS-resistant complexes ([6]; Silic-Benussi, unpublished observations). This latter characteristic is a hallmark of proteins that assemble into transmembrane oligomeric α-helical bundles such as viroporins ([16], see below).

Fig. 2.

Effects of p13 function at the mitochondrial level: a working model. p13 is inserted in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IM) and generates an inward K+ current in mitochondria. This effect may result either from the direct channel-forming ability of p13 (upper part of the scheme) or by its influence on cellular K+ channels located in the mitochondria (lower part of the scheme). This effect leads to IM depolarization that in turn increases the activity of the electron transport chain (ETC) which, by increasing H+ extrusion, dampens the depolarizing effect of p13. Furthermore, increased ETC activity results in increased ROS production which, along with membrane depolarization, may lower the opening threshold of the permeability transition pore (PTP).

5. Effects of p13 on cell turnover and transformation

Expression of p13 in HeLa cells and Jurkat T-cells results in reduced proliferation rates and increased sensitivity to apoptosis induced by ceramide and FasL [17], [18]. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that p13 may act by lowering the threshold of PTP opening, as observed in isolated mitochondria. Furthermore, p13 was recently confirmed to affect ROS production when expressed in cells (Silic-Benussi et al., unpublished observations).

Mitochondria play a pivotal role in the control of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis [reviewed by [19]]. As p13 affects mitochondrial Δψ, the driving force of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, we also asked whether the protein affects calcium homeostasis. Consistent with this hypothesis, p13 increases phosphorylation of the CREB transcription factor on serine 133 in response to histamine [18], an event that is mediated by the Ca2+-dependent activation of CAM kinase. These data are supported by recent studies that showed that p13 alters mitochondrial Δψ and Ca2+ uptake in the context of living cells (Biasiotto et al., unpublished observations). In analogy with other properties described for p13, these effects depend on the protein’s amphipathic α-helical domain. These findings reinforce the idea that p13 may play an important role in controlling cell signalling, activation and proliferation.

The properties described for p13 are of interest in the general context of tumour virology, as all of the human tumour viruses express at least one mitochondrial protein, some of which alter mitochondrial ion permeability and/or membrane potential, either through direct channel-forming activity or through interactions with endogenous channels. Consistent with the central role of mitochondria in energy production, cell death, calcium homeostasis, and redox potential, these proteins have profound effects on host cell physiology [3].

6. Mitochondrial K+ channels and cell turnover

The possibility that p13 might control cell turnover by affecting mitochondrial K+ permeability and ROS production is also consistent with the fact that mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium (mitoKATP) channels are involved in controlling cell survival and death [20]. mitoKATP channels are, in fact, strongly implicated in the protection from apoptosis that characterizes ischemic preconditioning in the heart. Although the molecular composition of mitoKATP channels is still elusive, recent findings suggest that mitoKATP may be functionally connected to the PTP and influence apoptosis induced through PTP opening [21]. These findings are consistent with results of a study demonstrating that p13 significantly inhibited the growth of experimental tumors in vivo [18].

7. Viral channel proteins: functional comparison of p13 with viroporins

A growing number of animal viruses have been shown to encode “viroporins”, a class of small hydrophobic integral membrane proteins characterized by at least one amphipathic α-helix [16]. Upon membrane insertion, viroporins oligomerize and assemble into pores that control membrane permeability (reviewed in [16]). The properties of viroporins suggest that they might represent ancestors of more complex cellular channels in which the pore is formed by a bundle of transmembrane helixes contained in a single protein rather than by a multimeric bundle of separate proteins.

Although direct channel activity of HTLV-1 p13 has not yet been investigated, its structure and effects on membrane K+ permeability (see above) suggest that it may act as a viroporin. In general, viroporins described so far act at two main levels: (i) enhancement of virion morphogenesis, by promoting viral entry and/or release of viral particles and (ii) control of host cell apoptosis. The ability of p13 to influence the response of cells to apoptotic stimuli suggests that it might fall into the second category of viroporins, along with PB1-F2 protein of Influenza A virus (IAV), 2B protein of poliovirus and Vpr of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1). Indeed, an increasing number of animal viruses have been shown to trigger apoptosis in infected cells at late stages of infection [22], examples include poliovirus and coxsackievirus [23], [24], alphaviruses, coronaviruses, influenza viruses and HCV [25], [26], [27], [28].

The PB1-F2 protein of Influenza A virus (IAV) is encoded by an alternative reading frame of the PB1 polymerase gene. PB1-F2 localizes in the nucleus, cytosol and mitochondria of infected cells. PB1-F2 is conserved in most mammalian and avian IAV isolates as a 78–90 amino acid protein, while it is not present in the influenza B virus strains [29]. PB1-F2 contains an amphipathic helix spanning residues 69–83, is targeted to mitochondria and triggers cell death, all features which are reminiscent of HTLV-1 p13 [29]. Although the function(s) of PB1-F2 in IAV biology are not fully elucidated at present, the fact that the protein induces apoptosis in human monocytes [30], [31] suggests that it might play a role in inhibiting the immune response towards IAV-infected cells [29]. Although PB1-F2 is not essential for viral replication in vitro, it increases viral pathogenicity in mice [32], [33]. Interestingly, a single amino acid mutation in PB1-F2 (asparagine 66 to serine) is sufficient to confer a highly pathogenic phenotype to IAV [34], [35]. Furthermore, PB1-F2 coded by the IAV that caused the 1918 influenza pandemic was shown to enhance secondary bacterial pneumonia [36], a major cause of death in IAV-infected individuals. More recently it was shown that phosphorylation of PB1-F2 by protein kinase C is essential for the apoptosis-promoting activity of PB1-F2 in monocytes [37]. This finding suggests that the activity of PB1-F2 might be controlled through the engagement of specific signal transduction pathways.

In analogy to other viroporins, the non-structural 2B protein of poliovirus contains a lysine-rich amphipathic domain that is conserved among 2B homologues of other members of the Picornaviridae family [38], [39]. This protein exhibits pore-forming activity that was mapped to a small amphipathic region which permeabilizes the plasma membrane to small solutes [40]. The 2B protein is also partially localized to mitochondria, alters mitochondrial membrane permeability and morphology, triggers cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation and induces apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. The observations made for 2B suggest that the pro-apoptotic activity of some viroporins may depend on their translocation to mitochondria and permeabilization of mitochondrial membranes [41]. The pore-forming domain of 2B was also shown to translocate across the plasma membrane [40], an effect that might be linked to its pore-forming activity.

Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) Vpr is a 14-kDa multifunctional protein that is detected in the nucleus, mitochondria, and in mature viral particles. Vpr contains three α-helices (amino acids 17–33, 38–50 and 56–77) surrounded by flexible N- and C-terminal domains, and folded around a hydrophobic core [42]. Exposure of isolated mitochondria or intact cells to Vpr results in mitochondrial depolarization and release of pro-apoptotic proteins from mitochondria [43]. Induction of cell death and the permeability transition are dependent on a region of Vpr which includes the third α-helix and critical arginine residues (amino acids 52–96); both effects are blocked by BCL-2 and PTP inhibitors. Experiments carried out using ANT- or VDAC-defective yeast strains showed that Vpr-induced cell death is dependent on these proteins, which were proposed to be associated with the PTP [43]. In vitro studies showed that Vpr binds to ANT and form channels with it in artificial membranes. Interestingly, BCL-2 is able to interfere with the Vpr-ANT interaction and with Vpr’s pore-forming activity [44]. In addition to these effects, Vpr mediates nuclear targeting of the viral genome [45], although this activity has been challenged by more recent studies [46]. Furthermore, Vpr induces cell cycle arrest at the G2/M checkpoint through inactivation of the cyclin B-cdc2 complex [47], [48], [49]. The fact that HIV-1 viral production is upregulated in G2 [48] suggests that Vpr might increase viral replication by prolonging the G2 phase. In addition to inducing apoptosis in vitro [50], [51], Vpr exerts anti-tumor effects in vivo; this latter effect is seen in immunocompetent mice but not in nude or SCID mice, suggesting modulation of the immune response rather than a direct anti-proliferative/apoptotic action [52]. One obvious explanation for the multiple effects of Vpr might be linked to its multiple intracellular localizations. It would be particularly interesting to compare the processes controlling the localization of p13 and Vpr in mitochondria vs. the nucleus and determine if their effects on cell viability require nuclear targeting or result from mitochondrial-nuclear “retrograde signalling” [53].

8. Concluding remarks and future directions

Experimental data collected so far indicate that p13 mediates a complex chain of alterations that starts with mitochondrial K+ influx accompanied by an increase in respiratory chain activity and that can lead to enhanced production of ROS, PTP sensitization and cell death. The effects of p13 in cells reinforce the emerging concept that manipulation of mitochondrial function is a key point of convergence in tumor virus replication strategies.

One of the key questions that should be addressed by future studies is the molecular mechanism underlying p13’s effects on K+ permeability, i.e. whether p13 influences the activity of endogenous K+ channels or forms a channel itself. The latter possibility is suggested by results of biochemical studies described in Ref. [6] and by structural analogies of p13 with viroporins. To this end biophysical experiments in artificial phospholipid membranes should provide useful information. Furthermore, the structure of the protein in the context of mitochondrial membranes should be tested by NMR and/or crystallographic analyses, which should also contribute to the understanding of the topology of the protein in the membrane and its intermolecular interactions. Another point that deserves further studies is the link between the K+ short circuit in mitochondria and the increase in ROS production, a finding that appears to contrast with studies demonstrating that depolarization induced by protonophores results in reduced ROS production. In the context of the viral life cycle, p13 might be important in controlling the turnover and tumor transformation of infected cells, a possibility that could be tested by comparing the replication and pathogenic properties of wild-type vs. p13-knock-out HTLV-1 molecular clones in an appropriate animal model.

Acknowledgments

We thank Luigi Chieco-Bianchi, Luca Settimo and Paolo Bernardi for discussions. This work was supported by grants from the European Union (‘The role of chronic infections in the development of cancer’; Contract No. 2005-018704), the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), the Ministero per l’Università e la Ricerca Scientifica, e Tecnologica Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale, the Istituto Superiore di Sanità AIDS research program, and the University of Padova. This paper is dedicated to the memory of David Derse, who generously provided reagents and ideas for our studies of HTLV-1 biology and pathogenesis.

References

- 1.Saggioro D., Silic-Benussi M., Biasiotto R., D’Agostino D.M., Ciminale V. Control of cell death pathways by HTLV-1 proteins. Front. Biosci. 2009;14:3338–3351. doi: 10.2741/3456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicot C., Harrod R.L., Ciminale V., Franchini G. Human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type 1 nonstructural genes and their functions. Oncogene. 2005;24:6026–6034. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Agostino D.M., Bernardi P., Chieco-Bianchi L., Ciminale V. Mitochondria as functional targets of proteins coded by human tumor viruses. Adv. Cancer Res. 2005;94:87–142. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(05)94003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Agostino D.M., Ciminale V., Pavlakis G.N., Chieco-Bianchi L. Intracellular trafficking of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev protein: involvement of continued rRNA synthesis in nuclear retention. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 1995;11:1063–1071. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M.R., Appel R.D., Bairoch A. ProteiN IDENTIFICATION AND ANALYSIS TOOLS On the ExPASy Server. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Agostino D.M. Mitochondrial alterations induced by the p13II protein of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. Critical role of arginine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:34424–34433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciminale V., Zotti L., D’Agostino D.M., Ferro T., Casareto L., Franchini G., Bernardi P., Chieco-Bianchi L. Mitochondrial targeting of the p13II protein coded by the x-II ORF of human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I) Oncogene. 1999;18:4505–4514. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scherf T., Kasher R., Balass M., Fridkin M., Fuchs S., Katchalski-Katzir E. A beta -hairpin structure in a 13-mer peptide that binds alpha -bungarotoxin with high affinity and neutralizes its toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:6629–6634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111164298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koralnik I.J., Fullen J., Franchini G. The p12I, p13II, and p30II proteins encoded by human T-cell leukemia/lymphotropic virus type I open reading frames I and II are localized in three different cellular compartments. J. Virol. 1993;67:2360–2366. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2360-2366.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghorbel S., Sinha-Datta U., Dundr M., Brown M., Franchini G., Nicot C. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I p30 nuclear/nucleolar retention is mediated through interactions with RNA and a constituent of the 60 S ribosomal subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:37150–37158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silic-Benussi M. Modulation of mitochondrial K(+) permeability and reactive oxygen species production by the p13 protein of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:947–954. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontaine E., Eriksson O., Ichas F., Bernardi P. Regulation of the permeability transition pore in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Modulation By electron flow through the respiratory chain complex i. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12662–12668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szewczyk A., Jarmuszkiewicz W., Kunz W.S. Mitochondrial potassium channels. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:134–143. doi: 10.1002/iub.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou X., Foley S., Cueto M., Robinson M.A. The human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I) X region encoded protein p13(II) interacts with cellular proteins. Virology. 2000;277:127–135. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefebvre L., Ciminale V., Vanderplasschen A., D’Agostino D., Burny A., Willems L., Kettmann R. Subcellular localization of the bovine leukemia virus R3 and G4 accessory proteins. J. Virol. 2002;76:7843–7854. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7843-7854.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez M.E., Carrasco L. Viroporins. FEBS Lett. 2003;552:28–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00780-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiraragi H., Michael B., Nair A., Silic-Benussi M., Ciminale V., Lairmore M. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 mitochondrion-localizing protein p13II sensitizes Jurkat T cells to Ras-mediated apoptosis. J. Virol. 2005;79:9449–9457. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9449-9457.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silic-Benussi M. Suppression of tumor growth and cell proliferation by p13II, a mitochondrial protein of human T cell leukemia virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:6629–6634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305502101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giacomello M., Drago I., Pizzo P., Pozzan T. Mitochondrial Ca2+ as a key regulator of cell life and death. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1267–1274. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ardehali H., O’Rourke B. Mitochondrial K(ATP) channels in cell survival and death. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005;39:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akao M., O’Rourke B., Kusuoka H., Teshima Y., Jones S.P., Marban E. Differential actions of cardioprotective agents on the mitochondrial death pathway. Circ. Res. 2003;92:195–202. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000051862.16691.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Brien V. Viruses and apoptosis. J. Gen. Virol. 1998;79(Pt 8):1833–1845. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-8-1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agol V.I. Two types of death of poliovirus-infected cells: caspase involvement in the apoptosis but not cytopathic effect. Virology. 1998;252:343–353. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carthy C.M., Granville D.J., Watson K.A., Anderson D.R., Wilson J.E., Yang D., Hunt D.W., McManus B.M. Caspase activation and specific cleavage of substrates after coxsackievirus B3-induced cytopathic effect in HeLa cells. J. Virol. 1998;72:7669–7675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7669-7675.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grandgirard D., Studer E., Monney L., Belser T., Fellay I., Borner C., Michel M.R. Alphaviruses induce apoptosis in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells: evidence for a caspase-mediated, proteolytic inactivation of Bcl-2. EMBO J. 1998;17:1268–1278. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An S., Chen C.J., Yu X., Leibowitz J.L., Makino S. Induction of apoptosis in murine coronavirus-infected cultured cells and demonstration of E protein as an apoptosis inducer. J. Virol. 1999;73:7853–7859. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7853-7859.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalkeri G., Khalap N., Garry R.F., Fermin C.D., Dash S. Hepatitis C virus protein expression induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells. Virology. 2001;282:26–37. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wurzer W.J., Planz O., Ehrhardt C., Giner M., Silberzahn T., Pleschka S., Ludwig S. Caspase 3 activation is essential for efficient influenza virus propagation. EMBO J. 2003;22:2717–2728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen W. A novel influenza A virus mitochondrial protein that induces cell death. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowy R.J. Influenza virus induction of apoptosis by intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2003;22:425–449. doi: 10.1080/08830180305216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zamarin D., Garcia-Sastre A., Xiao X., Wang R., Palese P. Influenza virus PB1-F2 protein induces cell death through mitochondrial ANT3 and VDAC1. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman J.R. The PB1-F2 protein of Influenza A virus: increasing pathogenicity by disrupting alveolar macrophages. Virol. J. 2007;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zamarin D., Ortigoza M.B., Palese P. Influenza A virus PB1-F2 protein contributes to viral pathogenesis in mice. J. Virol. 2006;80:7976–7983. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00415-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conenello G.M., Palese P. Influenza A virus PB1-F2: a small protein with a big punch. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conenello G.M., Zamarin D., Perrone L.A., Tumpey T., Palese P. A single mutation in the PB1-F2 of H5N1 (HK/97) and 1918 influenza A viruses contributes to increased virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1414–1421. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McAuley J.L., Hornung F., Boyd K.L., Smith A.M., McKeon R., Bennink J., Yewdell J.W., McCullers J.A. Expression of the 1918 influenza A virus PB1-F2 enhances the pathogenesis of viral and secondary bacterial pneumonia. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitzner D. Phosphorylation of the influenza A virus protein PB1-F2 by PKC is crucial for apoptosis promoting functions in monocytes. Cell. Microbiol. 2009;11:1502–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nieva J.L., Agirre A., Nir S., Carrasco L. Mechanisms of membrane permeabilization by picornavirus 2B viroporin. FEBS Lett. 2003;552:68–73. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00852-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Kuppeveld F.J., van den Hurk P.J., Zoll J., Galama J.M., Melchers W.J. Mutagenesis of the coxsackie B3 virus 2B/2C cleavage site: determinants of processing efficiency and effects on viral replication. J. Virol. 1996;70:7632–7640. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7632-7640.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madan V., Sanchez-Martinez S., Carrasco L., Nieva J.L. A peptide based on the pore-forming domain of pro-apoptotic poliovirus 2B viroporin targets mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boya P., Pauleau A.L., Poncet D., Gonzalez-Polo R.A., Zamzami N., Kroemer G. Viral proteins targeting mitochondria: controlling cell death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1659:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morellet N., Bouaziz S., Petitjean P., Roques B.P. NMR structure of the HIV-1 regulatory protein VPR. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;327:215–227. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacotot E. The HIV-1 viral protein R induces apoptosis via a direct effect on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:33–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jain C., Belasco J.G. Structural model for the cooperative assembly of HIV-1 Rev multimers on the RRE as deduced from analysis of assembly-defective mutants. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:603–614. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gallay P., Stitt V., Mundy C., Oettinger M., Trono D. Role of the karyopherin pathway in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nuclear import. J. Virol. 1996;70:1027–1032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1027-1032.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamashita M., Emerman M. The cell cycle independence of HIV infections is not determined by known karyophilic viral elements. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bartz S.R., Rogel M.E., Emerman M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cell cycle control: Vpr is cytostatic and mediates G2 accumulation by a mechanism which differs from DNA damage checkpoint control. J. Virol. 1996;70:2324–2331. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2324-2331.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goh W.C., Rogel M.E., Kinsey C.M., Michael S.F., Fultz P.N., Nowak M.A., Hahn B.H., Emerman M. HIV-1 Vpr increases viral expression by manipulation of the cell cycle: a mechanism for selection of Vpr in vivo. Nat. Med. 1998;4:65–71. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He J., Choe S., Walker R., Di Marzio P., Morgan D.O., Landau N.R. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J. Virol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Poon B., Grovit-Ferbas K., Stewart S.A., Chen I.S. Cell cycle arrest by Vpr in HIV-1 virions and insensitivity to antiretroviral agents. Science. 1998;281:266–269. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart S.A., Poon B., Jowett J.B., Xie Y., Chen I.S. Lentiviral delivery of HIV-1 Vpr protein induces apoptosis in transformed cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:12039–12043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pang S. Anticancer effect of a lentiviral vector capable of expressing HIV-1 Vpr. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:3567–3573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z., Sekito T., Spirek M., Thornton J., Butow R.A. Retrograde signaling is regulated by the dynamic interaction between Rtg2p and Mks1p. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:401–411. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]