Case Presentation

A 10‐year‐old spayed female domestic shorthair cat was presented to a local veterinary practice with a history of persistent dyspnea and episodes of open‐mouth breathing that were initiated upon exertion or when handled. The dyspnea improved with oxygen therapy. Feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus test results were negative, and a feline coronavirus titer was positive. Previous vaccination for feline infectious peritonitis explained the positive coronavirus titer. A CBC was performed, and results were within reference limits except for mild leukocytosis (16.2×10 3 cells/μL, reference interval 5.0–12.0×10 3 cells/μL). Serum chemistry panel results were within normal limits except for mild azotemia (BUN 36 mg/dL, reference interval 8–24 mg/dL; creatinine 1.6 mg/dL, reference interval 0.1–1.1 mg/dL), hyperglycemia (168 mg/dL, reference interval 70–115 mg/dL), hyponatremia (142 mmol/L, reference interval 147–156 mmol/L), hypokalemia (3.7 mmol/L, reference interval 4.0–4.6 mmol/L), hypochloremia (106 mmol/L, reference interval 117–123 mmol/L), and hypophosphatemia (3.4 mg/dL, reference interval 3.9–6.1 mg/dL). Urinalysis was not performed. No heart murmur was audible upon auscultation of the thorax.

Thoracic ultrasound examination revealed a 2.2×1.9×2.0‐cm solid mass on the right heart base at the entrance of the cranial vena cava. Increased left ventricular wall thickening and mild pleural effusion also were noted. Ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of the mass was obtained for cytologic examination (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Fine‐needle aspirate of an intrathoracic mass from a cat. Wright‐Giesma, ×330.

Cytologic Interpretation

Two smears of the intrathoracic mass aspirate were examined. One smear consisted of high numbers of bare nuclei in a peripheral blood background (Figure 1A). The other smear was highly cellular and consisted of many bare nuclei and moderate numbers of intact epithelial cells in a peripheral blood background (Figure 1B and Figure 1C). The epithelial cells were present primarily in small groups or clusters and had round, centrally placed, dark purple nuclei. Nuclei had moderately stippled chromatin and contained single prominent to discrete nucleoli. Cytoplasm was circumferential, faintly lavender‐gray, and finely granular, with faint but distinct cytoplasmic borders. Some cells contained numerous round intracytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 1D). Mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis were observed. The cytologic findings were suggestive of a neuroendocrine tumor, derived from amine precursor uptake and decar‐boxylase (APUD) cells. Based on the location of the tumor and cytologic findings, chemodectoma was the tentative diagnosis. Other differential diagnoses included ectopic thyroid gland neoplasia and thymoma. The lack of tyrosine granules and the lack of lymphoid cells made these diagnoses less likely.

Gross and Histopathologic Findings

One week after the initial examination, the cat was referred to a veterinary surgeon for possible removal of the mass. The cat was cyanotic upon presentation. Thoracic radiographs revealed marked pleural effusion. After induction with general anesthesia, 60 mL of chy‐lous fluid was removed via thoracocentesis. A right fifth intercostal space thoracotomy was performed. Upon opening the thorax, another 300 mL of chylous fluid was removed. The mass, located just cranial to the heart near the entrance of the vena cava, was dissected and removed. Upon exploration of the thorax, no other masses were found and the lungs appeared normal. The cat died suddenly the following morning; necropsy was not performed. The mass removed at the time of surgery was submitted for histopathology.

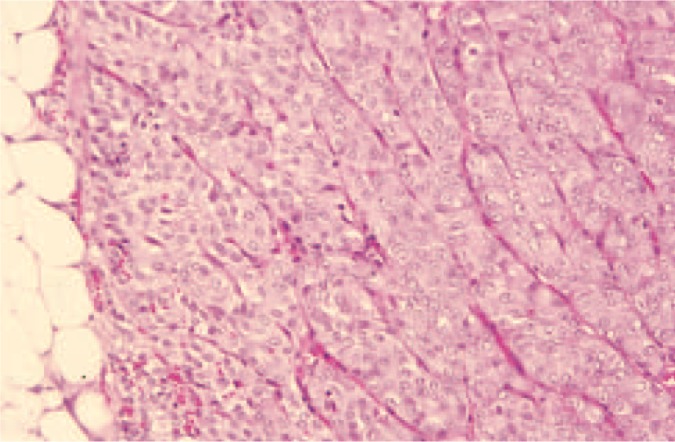

The histopathologic diagnosis of the mass was chemodectoma. Pertinent histologic findings included a neoplastic proliferation of densely packed polyhedral cells arranged in packets and sheets separated with fine fibrovascular trabeculae (Figure 2). The cells had round to slightly oval nuclei containing stippled chromatin and single prominent nucleoli with a moderate amount of pale cytoplasm and indistinct cytoplasmic margins.

Figure 2.

Histologic section of the intrathoracic mass. Packets of polyhedral cells are separated by fine fibrovascular trabeculae. The histopathologic diagnosis was chemodectoma. Hematoxylin and eosin, ×66.

Discussion

Heart base tumors are uncommon in cats. Differential diagnoses for tumors at the base of the heart include lymphoma, thymoma, ectopic thyroid carcinoma, hemangiosarcoma, and chemodectoma. 1 Chemodec‐tomas are neoplasms of chemoreceptor tissue, with the largest accumulation of these cells found in the aortic and carotid bodies. 2 Aortic body chemodectomas are rare in the cat; only 6 cases have been reported in the literature. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Presenting history often includes progressive or worsening dyspnea, anorexia, lethargy, and weight loss. Clinical findings include labored breathing, open‐mouth breathing, coughing, pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, or rarely pulmonary edema. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6

No breed predilection has been noted in cats with chemodectoma. Ages of affected cats range from 7 to 16 years, and females are slightly more predisposed. Human beings living at high altitudes seem to be predisposed. Brachycephalic dog breeds, especially Boxers and Boston Terriers, also seem to be predisposed. Brachycephaly does not appear to be a contributing factor in cats, although brachycephalic conformation is present in many feline breeds. 3

Chemodectomas are slow growing and locally invasive, with moderate metastatic potential. Three of 6 cats had metastasis: 1 in the sternal lymph node, and 2 in the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, and lungs. 3 , 4 , 6 Metastasis is uncommon in human patients but occurs in approximately 22% of dogs, with the lungs being the most common organ affected. 7 In dogs, chemodectomas often are associated with other endocrine neoplasms, especially testicular tumors. 2 Although most chemodectomas were confirmed at necropsy (5/6) or surgical biopsy (1/6), 1 tumor was diagnosed based on cytology. 2 The cytologic appearance of the aspirate in the latter case was consistent with neoplasia of endocrine origin; differential diagnoses were chemodectoma and thyroid neoplasia. A cytologic description was not included in the report.

Treatment of chemodectomas may involve medical and/or surgical therapy. Radiation therapy has been used in people. 8 Complete surgical resection is rarely feasible because of the close proximity of chemorecep‐tor cells to the major vessels, and the marked invasive‐ness of the tumor. Prognosis is guarded. 6 Average survival times in dogs is approximately 12 months. 3 In cats, survival periods range from an immediate need for euthanasia to 13 months with surgical debulking and 19 months with subtotal pericardectomy.

Cytology appears to be a useful tool in the diagnosis of chemodectomas in cats. The tumors exfoliate high numbers of cells. Because the cells are fragile, many bare purple nuclei are usually seen. The intact epithelial cells have round purple nuclei with single prominent to discrete nucleoli, moderately abundant lavender‐gray finely granular to sometimes finely vacuolated cytoplasm, and faint but distinct cell borders. The appearance of the tumor in this cat was consistent with that of an endocrine tumor, and considering the location, chemodectoma was the most likely diagnosis. Multiple smears of cells from suspected chemodectomas should be made because of the fragility of the cells.

Citation: Intrathoracic mass in a cat [chemodectoma].

References

- 1. Paola JP, Hammer AS, Smeak DD, Merryman JI. Aortic body tumor causing pleural effusion in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1994; 30: 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tillson DM, Fingland RB, Andrews GA. Chemodectoma in a cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1994; 30: 586–590. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Willis R, Williams AE, Schwarz T, Patterson C, Wotton PR. Aortic body chemodectoma causing pulmonary edema in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 2001; 42: 20–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buergelt CD, Das KM. Aortic body tumor in a cat: a case report. Vet Pathol. 1968; 5: 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fossum TW, Miller MW, Rogers KS, Bonagura JD, Meurs KM. Chylothorax associated with right sided heart failure in 5 cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994; 204: 84–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tilley LP, Bond B, Patnaik AM, Liu AK. Cardiovascular tumors in the cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1981; 17: 1009–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blackmore J, Gorman NT, Kagan K, Hines S, Spencer C. Neurological complications of a chemodectoma in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1984; 184: 475–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Million RR, Cassini NJ, Clark JR. Cancer of the head and neck In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: Principles And Practice of Oncology. Philadelphia , Pa : JB Lippincott; 1989:488–590. [Google Scholar]