Abstract

Context

Conflict is prevalent between sports medicine professionals and coaching staffs regarding return-to-play decisions for athletes after injury in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I setting. The firsthand experiences of athletic trainers (ATs) regarding such conflict have not been fully investigated.

Objective

To better understand the outside pressures ATs face when making medical decisions regarding patient care and return to play after injury in the NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) setting.

Design

Qualitative study.

Setting

Semistructured one-on-one telephone interviews.

Patients or Other Participants

Nine ATs (4 men, 5 women; age = 31 ± 8 years [range = 24–48 years]; years certified = 9 ± 8).

Data Collection and Analysis

Interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed. Thematic analysis was completed phenomenologically. Researcher triangulation, peer review, and member checks were used to establish trustworthiness.

Results

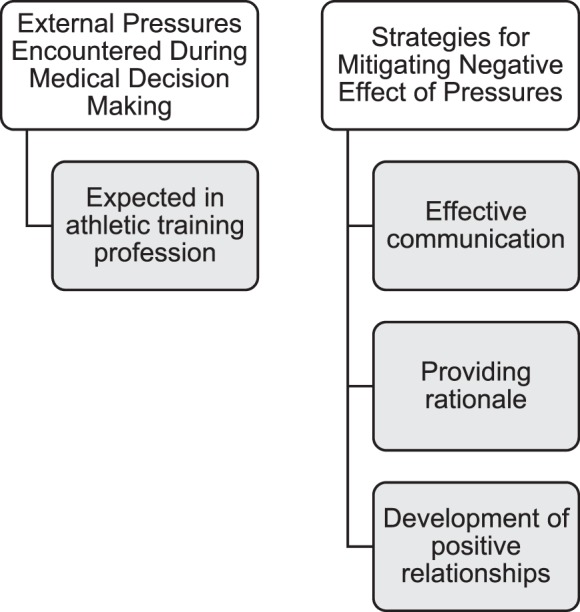

Two major themes emerged from the qualitative analysis: (1) pressure is an expected component of the Division I FBS AT role, and (2) strategies can be implemented to mitigate the negative effects of pressure. Three subthemes supported the second major theme: (1) ensuring ongoing and frequent communication with stakeholders about an injured athlete's status and anticipated timeline for return to play, (2) providing a rationale to coaches or administrations to foster an understanding of why specific medical decisions are being made, and (3) establishing positive relationships with coaches, athletes, and administrations.

Conclusions

External pressure regarding medical decisions was an anticipated occurrence for our sample. Such pressure was described as a natural part of the position, not negative but rather a product of the culture and environment of the Division I FBS setting. Athletic trainers who frequently face pressure from coaches and administration should use the aforementioned strategies to improve the workplace dynamic and foster an environment that focuses on patient-centered care.

Keywords: clinician-coach conflict, conflict of interest, organizational culture, role conflict

KEY POINTS

Responding athletic trainers (ATs) indicated that pressure from coaches was an expected and inherent part of the job.

Much of the pressure ATs faced resulted from coaches' eagerness to return athletes to play as quickly as possible after injury.

Common strategies ATs discussed for mitigating pressure were effective communication, including providing rationales for medical decisions and establishing rapport with all stakeholders.

The intervention of nonmedical personnel—particularly coaching staffs—in medical decisions and their pressure on health care professionals to return athletes to play has been anecdotally discussed and empirically studied.1,2 As a result, in 2016, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) ruled that athletic trainers (ATs) along with team physicians have the final decision regarding all medical care decisions, including return to play after an injury.3 This ruling not only places the health and safety of student-athletes in the hands of qualified health care providers but also, in theory, protects ATs and team physicians from pushback and conflict with coaching staffs and administrators.

The relationship between coaches and ATs has often been scrutinized because it has led to conflict over medical decisions and return to play.1,2 At the forefront of the conflict is the process of returning an athlete to competition after a concussion. Coaches are eager to have their student-athletes return to sport with little disruption to their playing time; however, the complexity of and limited predictability about symptom resolution may mean that a quick return is not always possible. In a report in The Chronicle of Higher Education,2 close to half of the surveyed ATs described feeling pressure from coaches to return their football athletes to the field after a concussion earlier than medically appropriate. A follow-up investigation by Kroshus et al1 indicated that approximately 54% of collegiate ATs responding to a survey had experienced pressure from coaches to prematurely return concussed athletes to play. Furthermore, clinicians (ATs and team physicians) employed in the NCAA Division III setting reported less pressure than those employed in Divisions I and II.1 More recent evidence4,5 supported the finding that ATs felt pressure from coaches to return athletes from injury sooner than medically appropriate. Although the injury might play only a small role, athletes with concussions or other less visible injuries may experience more pushback from the coaching staff.4

Much of the focus, both anecdotally and empirically, regarding the AT–coach relationship has been examined within the context of the NCAA football culture and at higher levels of competition, due to the associated pressures to “win at all costs” and the harsh reality that the jobs of coaches and athletic administrators often depend on team success. The Chronicle of Higher Education article2 and the findings of Kroshus et al,1 Pike et al,4 and Bowman et al5 highlight the need to better explore the dynamic between coaches and medical personnel, particularly as it relates to medical care decisions and returning athletes to sport after a concussion. However, much of the research1,2,4,5 on the topic has explored the relationships by simply quantifying the extent of conflict and pressures experienced by collegiate ATs. Missing in the literature is a more in-depth understanding of these pressures and the firsthand experiences of ATs regarding medical decision making.

Building on the current literature, we wanted to gain a better sense of the experiences of ATs working with all sports in the NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) setting regarding the pressures they face when providing medical care to their student-athletes and any conflicts that may result. Despite the evidence for the prevalence of conflict and pressure in athletic settings, investigators have focused on the climate in football rather than the FBS setting as a whole. Our study was guided by the following research questions: (1) Do ATs perceive there to be pressures placed on them when treating injuries and clearing athletes to return to play? (2) How are ATs managing their experiences with pressure to return student-athletes to play?

METHODS

A phenomenologic approach6 was used to better understand the experiences of ATs providing medical care in the NCAA Division I FBS setting. We selected this approach due to the complexity of the topic and our interest in gaining insight into these experiences through individual perspectives. The study protocol and procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the University of Lynchburg.

Participants

Participant recruitment was accomplished through purposeful and snowball sampling and guided by data saturation. To be included in the study, individuals had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) be employed as an AT at an NCAA Division I FBS institution and (2) provide medical care to 1 or more sponsored athletic teams. Athletic trainers who provided services to the college or university club sports program were excluded. Respondents employed in the NCAA Division I FBS setting were recruited for interviews as part of a larger study,4 and after participation, they were asked to contact peer ATs who matched our inclusion criteria and might be interested in volunteering. A total of 9 NCAA Division I FBS ATs (4 men, 5 women; age = 31 ± 8 years) completed our study. They were certified as ATs for 9 ± 8 years and had worked at their respective universities for 6 ± 7 years (median = 3.5 years) at the time of interview completion. Most of our participants were employed by public institutions (89%, n = 8) in various regions across the United States (Northeast = 1, Southeast = 5, West = 2, Southwest = 1). Additional demographic information regarding our participants can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interview Participant Demographics

|

Pseudonym |

Sex |

Job Title |

Age |

Years Certified |

Years in Current Position |

Sport Assignmenta |

University |

| Alex | M | Assistant AT | 27 | 6 | 1.5 | Wrestling | A |

| Camille | F | Assistant AD for sports medicine | 39 | 18 | 16 | Football | F |

| Catherine | F | Athletic training intern | 24 | 2 | 1 | Women's swimming, track and field | D |

| Evan | M | Director of football athletic training | 34 | 12 | 6 | Football | E |

| Lillian | F | Assistant AT | 26 | 5 | 3 | Rowing | B |

| Marcus | M | Associate AD for sports medicine | 48 | 26 | 20 | Football | G |

| Mariah | F | AT | 30 | 5 | 3.5 | Field hockey, women's lacrosse | C |

| Whitney | F | Graduate assistant AT | 24 | 2 | 2 | Volleyball | G |

| Xavier | M | Assistant AT | 30 | 7 | 4 | Football, men's or women's tennis | H |

Abbreviations: AD, athletic director; AT, athletic trainer; F, female; M, male.

The AT's full-time sport assignment. This excludes the sport(s) the AT assists with or supervises.

Instrumentation and Data-Collection Procedures

The semistructured interview guide (Table 2) was developed by the 3 members of the research team and built on previous work regarding organizational culture and conflict.1,7 The instrument was reviewed by an expert in the field of qualitative research who had extensive knowledge of the concepts being studied. The expert was a member of the research team but was not involved in conducting interviews or analyzing data. We also piloted the interview guide with 2 collegiate ATs before data collection to ensure that the questions were clear and would allow us to effectively address our purpose and research aims. After the pilot process, slight changes were made to the interview guide to improve flow and create a more natural dialogue between the participants and interviewer. As a result, data from the pilot participants were not included in the final analysis.

Table 2.

Stem Interview Guide Questionsa

| 1. You mentioned you ultimately report to (insert person's title here), does that have any impact on the return-to-play decisions you make? |

| a. If yes, how so? |

| b. If no, are there other factors that affect your return-to-play decision-making? |

| 2. Please describe the relationships you have with the athletes you work with. |

| 3. Do you receive pressures from your athletes regarding return-to-play decisions? |

| a. If yes, what are these pressures? |

| 4. Please describe the relationships you have with the coaches you work with. |

| a. How do you communicate and how often? |

| b. What are your interactions like? |

| c. How have the relationships changed over the course of your time working together? |

| 5. Do you ever feel pressure from your coaches regarding return-to-play decisions? |

| a. If yes, what are these pressures? |

| 6. If a new coach were hired, would you worry about you job security? Why or why not? |

| 7. Have you ever felt like your job depended on pleasing coaches? Why or why not? |

| 8. Has a coaching staff member ever criticized you in front of fellow staff members regarding your medical care? |

| a. If yes, can you describe the situation(s)? |

| 9. Do coaches generally understand the return-to-play decisions you make? |

| a. If yes, what indicated to you that they understand? |

| b. If no, what don't they understand about your decisions? |

| 10. Has a coach ever overruled your decision to terminate a player's participation during a practice or game? |

| a. If yes, can you describe the situation? |

| 11. Do you believe coaches have too much power over the health care professionals who care for athletes? Why or why not? |

| 12. Have athletic department members ever publicly criticized your medical decisions? |

| 13. Have athletic department members ever suggested that your athletes be sent to other medical professionals outside of your sports medicine team to seek advice? |

| 14. Have you ever felt like you needed to choose between job security and the well-being of your patients? Why or why not? |

| 15. Have you ever been fired or demoted over the medical decisions you have made? |

| 16. Have you ever made a return-to-play decision based on fear of getting sued? |

| 17. Are you familiar with any situation where health care for athletes by athletic trainers has been questioned publicly in the mainstream media? |

| a. If yes, does/did this alter your clinical decision-making? How so? |

Items are presented in their original format.

We selected a semistructured format to encourage open discussion between the participant and interviewer and to allow the interviewer to explore topics or experiences brought up during the interview that were not accounted for in the interview guide. After receipt of a signed consent form, the lead author conducted all interviews to ensure consistency. We audio recorded all interviews and had them transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company before data analysis as a means of reducing bias. We also provided all participants with pseudonyms and removed all identifying data from the presentation of the results to protect their identities.

Data Analysis

We used an interpretative phenomenological approach to analyze the data.8,9 Two researchers (A.M.P.L. and S.M.S.) independently analyzed the data after reading the transcripts several times to gain a sense of the participants' perceptions and verify that data saturation had been achieved. The data-analysis process involved coding the transcripts line by line to identify terms that related to our purpose and research questions. Similar codes were combined into categories. We then created overall themes from the categories as the final step in the analysis. Themes are presented with supporting quotes from the participants.

We used peer review, multiple-analyst triangulation, and member checks to ensure trustworthiness of the data- analysis procedure and presentation of the results.10 First, a peer who is an expert in qualitative research methods and organizational culture reviewed our interview guide and verified its content, clarity, and comprehensiveness. After analyzing the data, 2 members of the research team met to discuss their overall impressions and their interpretations of the emerging themes. The peer reviewer was then asked to examine the coding structure and verify the presentation of the results. After completion of the analysis and peer review, we openly discussed our preliminary findings during a conference call and came to 100% agreement on the coding structure, final themes, and presentation of the results. The themes and operational definitions were then shared with all 9 participants via e-mail, a process known as member checking. Participants were asked to review the findings and state whether they accurately reflected the experiences and information shared during the interview. After the review, all 9 ATs agreed with and supported our interpretation of the findings.

RESULTS

Two major themes and 4 subthemes (Figure) emerged from the data. First, participants were forthcoming about the external pressures they experienced from coaches to make medical care decisions. However, the theme was further explained and clarified as our participants indicated that pressure was an expected part of the role. In addition, ATs noted that pressure from coaches could be managed or prevented using 3 strategies: maintaining effective communication, providing rationales or explanations for specific medical decisions, and developing positive relationships.

Figure.

Experiences of athletic trainers regarding medical care decisions.

External Pressures Encountered During Medical Decision Making

Our participants reported feeling pressure from coaches, student-athletes, and athletic administrators regarding return to play and other medical care decisions. Greater pressure was perceived by those collegiate ATs providing medical care to revenue-generating sports such as football. Xavier's reflections highlighted the culture of Division I athletics and the pressure placed on the medical staff. When asked why he sometimes felt as if his job depended on pleasing coaches, he shared,

We seem to be in the business where the coaches get paid the most, get what they want the most. The athletic department is almost geared to cater to them . . . for the most part. Even though you don't work for the head coach, you in a sense kind of do. At least that's how it feels here.

Because it is related to overall athletic department success and revenue, the need to win in certain sports was viewed as a facilitator of coaches' pressure on the medical staff. Lillian explained,

I don't foresee that a rowing coach should have power to say who their athletic trainer is or isn't, whereas if it were a new basketball or football coach, I would be more concerned because those are your income sports . . . that's where you get all your money. I could see the university being more pressured to, if not fire the athletic trainer, at least shuffle them around [to a new sport].

It is interesting that Camille rationalized the idea of receiving pressure from her football coaches by discussing this topic from their perspective. She commented on the lack of job security for coaches compared with medical personnel at her institution as the impetus for the pressure she received from them:

In my setting, there's so much money riding on all of this. It's really insane when you stop and think about how many people's careers are riding on an 18- to 23-year-old person's athletic ability. I'm fortunate that I do have job security. They [coaches] don't. They're going to get fired if their team doesn't perform . . . so while I'm thinking about what this kid's knee is going to look like in 20 years . . . they're thinking, “Am I going to get fired at the end of the season?”

Expected in Athletic Training Profession

Our participants perceived that the pressure placed on them by coaches, student-athletes, and athletic administrators was a natural part of the position or job. They described this pressure not as negative but rather as an inherent aspect of the culture and environment of the NCAA Division I FBS setting. They believed that this pressure and questioning were rooted in eagerness to return an athlete to play or a quest for knowledge regarding the status of an athlete, not a desire to question the abilities and skillsets of the ATs. Many described the coach as the primary facilitator of the pressures to return athletes to play. Alex stated, “If they [coaches] question me, it's more of an inquiry . . . they're just trying to get all the information. They're trying to understand why I'm making a decision, which I'm perfectly fine with them doing.” Alex did not describe the pressure as constant but as centered on eagerness to return student-athletes to competition:

I mean they'll [coaches] give me some pressure, but it's never a pressure that makes me feel uncomfortable. It's sort of the same pressure the athlete gives you. That's their [coaches'] job to say, “Alright, we need to get this guy out here. Let's get him going,” but it's never demeaning or rude or feels like they're coming at me or trying to push me to make decisions.

Lillian perceived the pressures as “natural” for the coaches “to question things. I am not offended by anyone asking me, ‘Hey, can you get this student-athlete back for me?' [because] I am not going to risk the safety of the student-athlete just because a coach wants them back sooner.”

Our participants viewed the pressures from coaches and the student-athletes as eagerness for return-to-play decisions and described these pressures as “questioning the readiness of a student-athlete's ability to play and a timeline to return to play.” Camille shared, “It is the nature of my job that coaches question me and are not pleased with me, because generally I do not have good news. The question is never what are we doing, but rather when are they coming back to play?”

Strategies for Mitigating the Negative Effect of Pressures

Although the pressures perceived by our participants were viewed less as a negative aspect of the job and more as an inherent part, strategies to mitigate pressure and its negative effects were discussed. Three primary strategies emerged: (1) Maintaining effective communication with coaches and student-athletes, (2) providing rationales or explanations for decision making, and (3) developing positive relationships.

Maintaining Effective Communication

Ongoing and frequent communication with key stakeholders related to the status of injured athletes and return-to-play timelines was a strategy for mitigating conflict. Alex used proactive communication to reduce the questions surrounding his decisions regarding medical care:

I always make sure I go up to their [coaches'] office with an injury report. If there's an injury here or there, I have a group text that I'll send them just with some updates. . . . I just make sure I talk to them [coaches] before practice so they know what the plan is for everybody that's currently injured or newly injured.

Lillian described a similar strategy of proactive, open communication with her coaches:

If there's ever a time that someone is injured, I present the coaches with ideas [like] “We can either pull them out of everything and shut them down” or “I don't think it's that serious . . . we can pull them out of land practices and have them cross-train.” We've built a good back-and-forth [communication] about that kind of stuff. They [coaches] understand I'm not trying to hold people out [of participation] unnecessarily.

Mariah reflected on the importance of communication through an open dialogue with the coach regarding medical care:

I'm very open [and] willing to have conversations. . . . If they [coaches] want to ask questions, I'm more than happy to discuss it with them. I'm open to communicate and I'm willing to ask questions and admit when I don't know the answer. I think [that] probably gives them [coaches] more confidence [in me], because they know if I don't know, I'm not afraid to ask [others].

Respondents shared strategies for reducing conflict during return to play by engaging with the coaching staff and being upfront and honest. Regardless of the status of the injured student-athlete, Evan felt that coaches needed to be aware:

It comes down to communication . . . saying, ‘Hey, listen coach, if they [athlete] don't practice this Tuesday, I'm not very optimistic about them being ready for Saturday.' That sets it up a little bit to give the coaches some time to soak it in and prepare and make adjustments. . . . I think that's probably been the best thing for me, is just being on the forefront of communication and letting him [coach] know what the plan is.

Providing a Rationale

Participants recognized that coaches and athletes might not be happy with their medical decisions all the time, but having a reason for the decision and discussing it openly were key components for developing and fostering their understanding. Marcus shared, “there's been some heated discussions [between coaches and ATs] before about what we're seeing, and as soon as we tell them why we're feeling a certain way and what's indicated, they've usually backed off.” Evan remarked on the importance of communicating the reasons behind decision making, especially regarding return to play:

you're [as the AT] fielding a lot of questions [from coaches] . . . you're on the hot seat, if you will, so there is some pressure in that . . . you just got to be able to explain it [medical decision] as to why and what your logic is. Usually that helps.”

Being prepared to answer questions and to defend decision making were used by many of the ATs as a means to reduce conflict and improve the relationship with the coaching staff. Camille shared,

As long as I'm prepared to have the answers to their [coaches'] foreseeable questions [regarding an injured athlete], like “This is what's going on, this is our plan, and once we have a diagnosis, this is my anticipated timeline,” I generally get very little pushback from those coaches. As long as I have a logical, reasonable explanation [for a decision] and then at least entertained his thought and explained what we were doing instead . . . he would be more agreeable.

“Logical, reasonable explanations” can assist ATs in reducing conflict over return-to-play decisions, as well as medical care.

Developing Positive Relationships

Our participants emphasized the importance of developing effective relationships with coaches, student-athletes, and administration to mitigate pushback or pressure. Trust was frequently brought up as a necessary factor in these relationships. In reference to reducing conflicts between herself and the coaching staff, Mariah said, “my coaches trust my judgment, and they know that I do not try to tell them how to coach, and they don't try to tell me how to be an athletic trainer.” She felt that “collaborating” with the coaches was helpful in building a positive relationship. Similarly, Camille discussed the positive relationship she had with the coaches, which was built on their trusting her judgment and supporting her decisions. She noted, “It's mutual respect. I understand it's their [coaches'] job to push them [athletes]. They understand it's my job to keep people safe. It's taken time to build trust.” Alex reflected on the evolution of his relationship with the coaches, which did not happen overnight but did reduce the conflicts regarding medical care decisions: “I think when the coaches start to see your decisions that you are making and that they make sense and work out, trust begins to build.”

Our participants also stressed the importance of developing trusting, positive relationships with the student-athletes they treated. Lillian talked about building rapport and understanding their needs, which helped the student-athletes understand the injury process and reduced conflict that might have arisen:

I am a big believer in knowing them [athletes] before they're injured . . . that you should make some sort of attachment to them, so that they trust you with all different kinds of information. I'm trying to build a reputation with the rowing team [that] I'm here to help you no matter what.

DISCUSSION

Our primary focus was to explore the ATs' experiences regarding medical care decision making, particularly as it pertains to return to play. Growing evidence1,2,4,5 has indicated that ATs face pressure from coaches and other athletic administrators to return athletes to play, possibly before they are ready. Recognizing that ATs face such pressure, we also sought to better understand how ATs cope with these situations.

External Pressures Encountered During Medical Decision Making

Medical care decisions, especially regarding a student-athlete's readiness to return to play, are often the impetus for conflict between coaches and ATs.1,2,4,5 Our findings, in conjunction with other literature,4,5 showed that coaches were eager for their student-athletes to return from injury as soon as possible; however, for ATs in the collegiate setting, the eagerness was viewed at times as pressure. Our participants considered this was an inherent part of their job and expected it from coaches whose goals were successful programs. We4 previously described a similar circumstance, whereby ATs, regardless of the collegiate level, reported feeling pressure from coaches to return athletes to competition.

Our current findings, which align with our earlier results,4 should be shared with ATs currently employed in the collegiate setting, as well as with athletic training students who wish to work in this highly demanding environment. The pressures ATs face from coaches or athletic administrators do not appear to influence the final decision regarding care, and ATs continue to prioritize the health, well-being, and safety of their student-athletes. If future ATs are acclimated and oriented to the pressures they will face regarding return-to-play decisions, which most certainly will occur,1,4 they may be better able to stand firm in their decisions, mitigate conflict, and build professional relationships with coaching staffs to foster student-athlete success.

Strategies for Mitigating the Negative Effects of Pressure

Effective communication, providing rationales, and positive relationships emerged as useful strategies for ATs to reduce the negative effect of external pressures on the AT–coach relationship and their ability to do their jobs.

Communication skills are a foundational aspect of the AT role, given that ATs often must share information with a variety of members on the sports medicine team,11 including some who may not have medical knowledge but want to understand the injuries, treatments, and recovery trajectories. Clear communication has been reported as an important component of the relationship between ATs and coaches, especially when trying to reduce the occurrence of gender discrimination.12 Although discrimination and external pressures faced by ATs are distinctive and divergent concepts, the message centers on the importance of effective communication in creating positive, healthy working relationships with little conflict. Our participants shared the need to be open and honest when communicating with their coaching staffs; from their perspective, such a strategy reduced concerns about return-to-play decision making. Indeed, our participants verbalized the fact that coaches typically questioned medical decisions because they wanted to be “on the same page” with the health care professionals directing the medical plan. Providing coaches with adequate explanations and opportunities for input on the return-to-play plan, when appropriate, may allow coaches to support medical decisions while fostering trust and the belief that ATs have student-athletes' best interests at heart.

Education is an important element of the multifaceted role of the AT. This was evident in our participants' experiences and perspectives when they reflected on coaches' support of their clinical decisions after educational efforts. Involving coaches in the return-to-play process, particularly through regular injury status and progress updates, ultimately led to enhanced communication and a positive working relationship—key aspects to mitigating conflict. Pike et al4 found that when ATs were able to educate their coaches on the rationales behind their care and medical decisions, the coaches were supportive because they understood the reasons for the decisions.

Positive relationships were crucial to the development of a conflict-free, positive workplace environment. Trust and effective communication are required for the development of strong, professional relationships between ATs and coaches.13 Our participants described the need for both elements in their relationships but also noted that coaches must see that ATs' decision making regarding medical care was both effective and rooted in sound judgment. Time allowed the relationship to grow and enabled coaches to learn to respect the ATs' judgment. Therefore, we believe that coaches' trust in ATs is earned through effective communication and sound clinical reasoning skills. Although the trust-development process often takes time, we recommend that ATs make efforts to build trust with coaches as early as possible through face-to-face meetings where philosophies can be shared and goals can be discussed.12,13

Overall, our participants regarded the pressure they faced from coaches as an inherent, expected aspect of their job. The aforementioned strategies have been used to mitigate pressure, which can improve the work environment and the care provided to student-athletes. Despite these strategies, it is important to emphasize that ATs have the duty and responsibility to ensure that when pressure is exerted, it does not negatively affect the standard of care provided or the health and safety of student-athletes. Athletic trainers are encouraged to work collaboratively with administrators to identify additional means of reducing coaches' influences on medical decisions. Establishing a culture and environment that prioritizes the health and safety of student-athletes above all else demands efforts from both the medical (ie, athletic training staff, team physician) and institutional personnel.

Limitations and Future Research

An important limitation of this study is that we did not operationally define pressure for our participants. Although this was purposeful, because pressure can be viewed or felt differently by each person, this may have led to our participants referring to perceived versus actual instances of pressure from coaches. Our sample consisted of collegiate ATs working in the Division I FBS setting; therefore, we can only generalize our findings to athletic programs sponsoring football at the highest level of NCAA competition. Even though researchers often identified no differences between collegiate levels (eg, work-life conflict, burnout), it will be necessary to interview other ATs employed at various levels of collegiate sports to uncover commonalities as well as differences. It would also be interesting to interview ATs working with athletes in different sports. Our findings suggested that pressure was greatest for those working in revenue sports. Future investigators should determine how pressure on individual athletic teams to generate revenue might affect clinician–coach relationships. In addition, a more in-depth study of how pressure placed on clinicians, particularly ATs, can be managed or prevented from an institutional perspective is warranted. Finally, our results represent a snapshot in time and may not reflect the ebbs and flows of an athletic season; the pressure to win varies across the season and heightens during rivalry games and playoffs. A longitudinal design to assess the changing dynamics of the clinician–coach relationship would be informative when investigating experiences of pressure or conflict.

CONCLUSIONS

External pressure regarding medical decisions was an anticipated occurrence for the ATs we interviewed. Such pressure was described as a natural part of the position, not negative but rather a product of the culture and environment of the Division I FBS setting. Effectively communicating with coaches and providing rationales for medical decisions can facilitate the development of positive relationships with coaches, fostering cohesion within the team while reducing conflict and improving the care delivered to student-athletes. Athletic trainers who frequently face pressure from coaches and administration should use these strategies to improve workplace dynamics and create an environment that focuses on patient-centered care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the National Athletic Trainers' Association Research & Education Foundation for fully funding this study. We also thank the athletic trainers who took the time to participate and share their experiences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kroshus E, Baugh CM, Daneshvar DH, Stamm JM, Laursen RM, Austin SB. Pressure on sports medicine clinicians to prematurely return collegiate athletes to play after concussion. J Athl Train. 2015;50(9):944–951. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.6.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolverton B. Coach makes the call: athletic trainers who butt heads with coaches over concussion treatment take career hits. The Chronicle of Higher Education Web site. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Trainers-Butt-Heads-With/141333. Published September 2, 2013. Accessed April 26, 2019.

- 3.Robinson B. Return to play: who makes the decision? National Federation of State High School Associations Web site. https://www.nfhs.org/articles/return-to-play-who-makes-the-decision/. Published March 16, 2016. Accessed April 2, 2019.

- 4.Pike AM, Bowman TG, Mazerolle SM. Challenges faced by collegiate athletic trainers, part I: organizational conflict and clinical decision making. J Athl Train. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Bowman TG, Mazerolle SM, Pike AM, Register-Mihalik JK. Challenges faced by collegiate athletic trainers, part II: treating concussed student-athletes. J Athl Train. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Davidsen AS. Phenomenological approaches in psychology and health sciences. Qual Res Psychol. 2013;10(3):318–339. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2011.608466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Weuve C. Negative encounters in the workplace: recognizing and dealing with various forms of conflict in athletic training. Presented at: National Athletic Trainers' Association Clinical Symposia; June 28; Indianapolis, IN: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wimpenny P, Gass J. Interviewing in phenomenology and grounded theory: is there a difference? J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(6):1485–1492. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London, England: SAGE Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000;39(3):124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Courson R, Goldenberg M, Adams KG, et al. Inter-association consensus statement on best practices for sports medicine management for secondary schools and colleges. J Athl Train. 2014;49(1):128–137. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.1.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazerolle SM, Borland JF, Burton LJ. The professional socialization of collegiate female athletic trainers: navigating experiences of gender bias. J Athl Train. 2012;47(6):694–703. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-47.6.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander L. San Jose State University; CA: 2013. NCAA Division I Coaches and Athletic Trainers: An Examination of Professional Relationships and Knowledge of the Athletic Training Profession. [master's thesis] [Google Scholar]