Structure of the nCoV trimeric spike

The World Health Organization has declared the outbreak of a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) to be a public health emergency of international concern. The virus binds to host cells through its trimeric spike glycoprotein, making this protein a key target for potential therapies and diagnostics. Wrapp et al. determined a 3.5-angstrom-resolution structure of the 2019-nCoV trimeric spike protein by cryo–electron microscopy. Using biophysical assays, the authors show that this protein binds at least 10 times more tightly than the corresponding spike protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)–CoV to their common host cell receptor. They also tested three antibodies known to bind to the SARS-CoV spike protein but did not detect binding to the 2019-nCoV spike protein. These studies provide valuable information to guide the development of medical counter-measures for 2019-nCoV.

Science, this issue p. 1260

The overall structure of the 2019-nCoV spike (S) protein resembles that of SARS-CoV S, but 2019-nCoV S binds more tightly to the host receptor.

Abstract

The outbreak of a novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) represents a pandemic threat that has been declared a public health emergency of international concern. The CoV spike (S) glycoprotein is a key target for vaccines, therapeutic antibodies, and diagnostics. To facilitate medical countermeasure development, we determined a 3.5-angstrom-resolution cryo–electron microscopy structure of the 2019-nCoV S trimer in the prefusion conformation. The predominant state of the trimer has one of the three receptor-binding domains (RBDs) rotated up in a receptor-accessible conformation. We also provide biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV S protein binds angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) with higher affinity than does severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV S. Additionally, we tested several published SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies and found that they do not have appreciable binding to 2019-nCoV S, suggesting that antibody cross-reactivity may be limited between the two RBDs. The structure of 2019-nCoV S should enable the rapid development and evaluation of medical countermeasures to address the ongoing public health crisis.

The novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV has recently emerged as a human pathogen in the city of Wuhan in China’s Hubei province, causing fever, severe respiratory illness, and pneumonia—a disease recently named COVID-19 (1, 2). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 16 February 2020, there had been >51,000 confirmed cases globally, leading to at least 1600 deaths. The emerging pathogen was rapidly characterized as a new member of the betacoronavirus genus, closely related to several bat coronaviruses and to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (3, 4). Compared with SARS-CoV, 2019-nCoV appears to be more readily transmitted from human to human, spreading to multiple continents and leading to the WHO’s declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on 30 January 2020 (1, 5, 6).

2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike (S) protein to gain entry into host cells. The S protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a substantial structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host cell membrane (7, 8). This process is triggered when the S1 subunit binds to a host cell receptor. Receptor binding destabilizes the prefusion trimer, resulting in shedding of the S1 subunit and transition of the S2 subunit to a stable postfusion conformation (9). To engage a host cell receptor, the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of S1 undergoes hinge-like conformational movements that transiently hide or expose the determinants of receptor binding. These two states are referred to as the “down” conformation and the “up” conformation, where down corresponds to the receptor-inaccessible state and up corresponds to the receptor-accessible state, which is thought to be less stable (10–13). Because of the indispensable function of the S protein, it represents a target for antibody-mediated neutralization, and characterization of the prefusion S structure would provide atomic-level information to guide vaccine design and development.

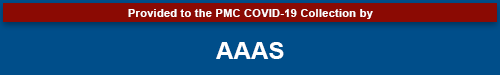

Based on the first reported genome sequence of 2019-nCoV (4), we expressed ectodomain residues 1 to 1208 of 2019-nCoV S, adding two stabilizing proline mutations in the C-terminal S2 fusion machinery using a previous stabilization strategy that proved effective for other betacoronavirus S proteins (11, 14). Figure 1A shows the domain organization of the expression construct, and figure S1 shows the purification process. We obtained ~0.5 mg/liter of the recombinant prefusion-stabilized S ectodomain from FreeStyle 293 cells and purified the protein to homogeneity by affinity chromatography and size-exclusion chromatography (fig. S1). Cryo–electron microscopy (cryo-EM) grids were prepared using this purified, fully glycosylated S protein, and preliminary screening revealed a high particle density with little aggregation near the edges of the holes.

Fig. 1. Structure of 2019-nCoV S in the prefusion conformation.

(A) Schematic of 2019-nCoV S primary structure colored by domain. Domains that were excluded from the ectodomain expression construct or could not be visualized in the final map are colored white. SS, signal sequence; S2′, S2′ protease cleavage site; FP, fusion peptide; HR1, heptad repeat 1; CH, central helix; CD, connector domain; HR2, heptad repeat 2; TM, transmembrane domain; CT, cytoplasmic tail. Arrows denote protease cleavage sites. (B) Side and top views of the prefusion structure of the 2019-nCoV S protein with a single RBD in the up conformation. The two RBD down protomers are shown as cryo-EM density in either white or gray and the RBD up protomer is shown in ribbons colored corresponding to the schematic in (A).

After collecting and processing 3207 micrograph movies, we obtained a 3.5-Å-resolution three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of an asymmetrical trimer in which a single RBD was observed in the up conformation. (Fig. 1B, fig. S2, and table S1). Because of the small size of the RBD (~21 kDa), the asymmetry of this conformation was not readily apparent until ab initio 3D reconstruction and classification were performed (Fig. 1B and fig. S3). By using the 3D variability feature in cryoSPARC v2 (15), we observed breathing of the S1 subunits as the RBD underwent a hinge-like movement, which likely contributed to the relatively poor local resolution of S1 compared with the more stable S2 subunit (movies S1 and S2). This seemingly stochastic RBD movement has been captured during structural characterization of the closely related betacoronaviruses SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, as well as the more distantly related alphacoronavirus porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) (10, 11, 13, 16). The observation of this phenomenon in 2019-nCoV S suggests that it shares the same mechanism of triggering that is thought to be conserved among the Coronaviridae, wherein receptor binding to exposed RBDs leads to an unstable three-RBD up conformation that results in shedding of S1 and refolding of S2 (11, 12).

Because the S2 subunit appeared to be a symmetric trimer, we performed a 3D refinement imposing C3 symmetry, resulting in a 3.2-Å-resolution map with excellent density for the S2 subunit. Using both maps, we built most of the 2019-nCoV S ectodomain, including glycans at 44 of the 66 N-linked glycosylation sites per trimer (fig. S4). Our final model spans S residues 27 to 1146, with several flexible loops omitted. Like all previously reported coronavirus S ectodomain structures, the density for 2019-nCoV S begins to fade after the connector domain, reflecting the flexibility of the heptad repeat 2 domain in the prefusion conformation (fig. S4A) (13, 16–18).

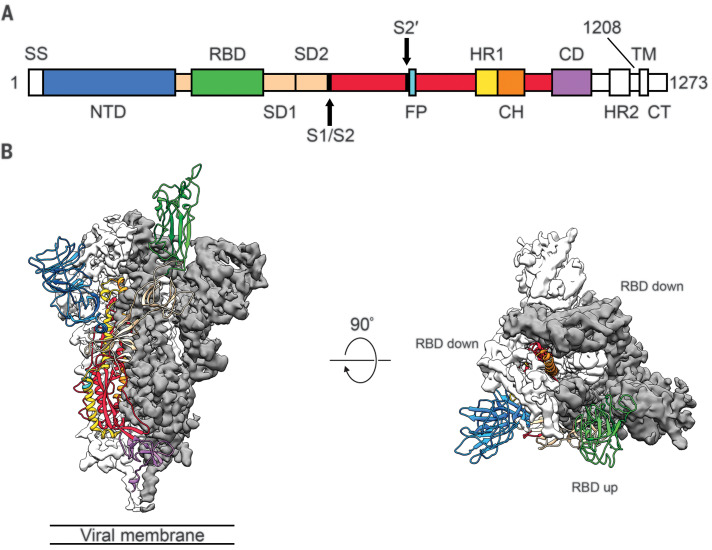

The overall structure of 2019-nCoV S resembles that of SARS-CoV S, with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 3.8 Å over 959 Cα atoms (Fig. 2A). One of the larger differences between these two structures (although still relatively minor) is the position of the RBDs in their respective down conformations. Whereas the SARS-CoV RBD in the down conformation packs tightly against the N-terminal domain (NTD) of the neighboring protomer, the 2019-nCoV RBD in the down conformation is angled closer to the central cavity of the trimer (Fig. 2B). Despite this observed conformational difference, when the individual structural domains of 2019-nCoV S are aligned to their counterparts from SARS-CoV S, they reflect the high degree of structural homology between the two proteins, with the NTDs, RBDs, subdomains 1 and 2 (SD1 and SD2), and S2 subunits yielding individual RMSD values of 2.6 Å, 3.0 Å, 2.7 Å, and 2.0 Å, respectively (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Structural comparison between 2019-nCoV S and SARS-CoV S.

(A) Single protomer of 2019-nCoV S with the RBD in the down conformation (left) is shown in ribbons colored according to Fig. 1. A protomer of 2019-nCoV S in the RBD up conformation is shown (center) next to a protomer of SARS-CoV S in the RBD up conformation (right), displayed as ribbons and colored white (PDB ID: 6CRZ). (B) RBDs of 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV aligned based on the position of the adjacent NTD from the neighboring protomer. The 2019-nCoV RBD is colored green and the SARS-CoV RBD is colored white. The 2019-nCoV NTD is colored blue. (C) Structural domains from 2019-nCoV S have been aligned to their counterparts from SARS-CoV S as follows: NTD (top left), RBD (top right), SD1 and SD2 (bottom left), and S2 (bottom right).

2019-nCoV S shares 98% sequence identity with the S protein from the bat coronavirus RaTG13, with the most notable variation arising from an insertion in the S1/S2 protease cleavage site that results in an “RRAR” furin recognition site in 2019-nCoV (19) rather than the single arginine in SARS-CoV (fig. S5) (20–23). Notably, amino acid insertions that create a polybasic furin site in a related position in hemagglutinin proteins are often found in highly virulent avian and human influenza viruses (24). In the structure reported here, the S1/S2 junction is in a disordered, solvent-exposed loop. In addition to this insertion of residues in the S1/S2 junction, 29 variant residues exist between 2019-nCoV S and RaTG13 S, with 17 of these positions mapping to the RBD (figs. S5 and S6). We also analyzed the 61 available 2019-nCoV S sequences in the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data database (https://www.gisaid.org/) and found that there were only nine amino acid substitutions among all deposited sequences. Most of these substitutions are relatively conservative and are not expected to have a substantial effect on the structure or function of the 2019-nCoV S protein (fig. S6).

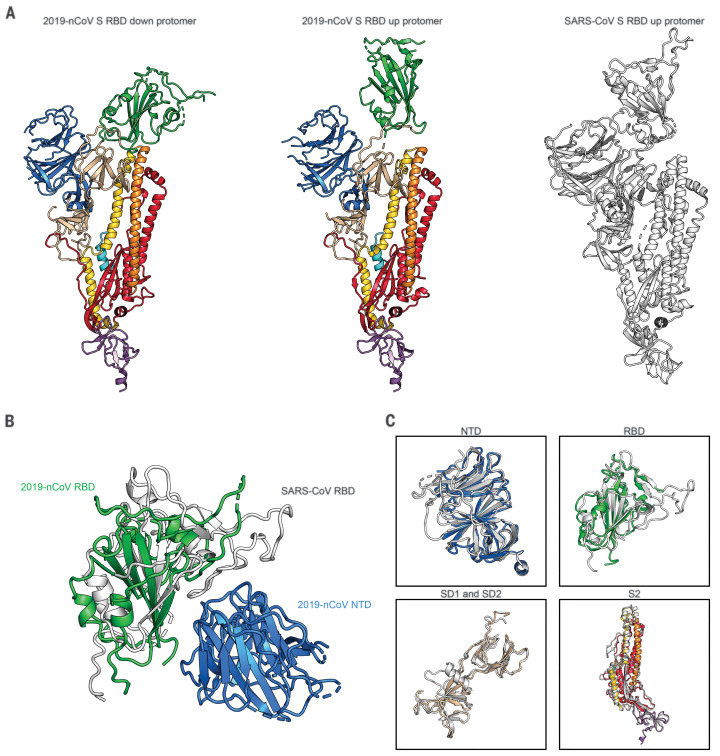

Recent reports demonstrating that 2019-nCoV S and SARS-CoV S share the same functional host cell receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (22, 25–27), prompted us to quantify the kinetics of this interaction by surface plasmon resonance. ACE2 bound to the 2019-nCoV S ectodomain with ~15 nM affinity, which is ~10- to 20-fold higher than ACE2 binding to SARS-CoV S (Fig. 3A and fig. S7) (14). We also formed a complex of ACE2 bound to the 2019-nCoV S ectodomain and observed it by negative-stain EM, which showed that it strongly resembled the complex formed between SARS-CoV S and ACE2 that has been observed at high resolution by cryo-EM (Fig. 3B) (14, 28). The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human to human (1); however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility.

Fig. 3. 2019-nCoV S binds human ACE2 with high affinity.

(A) Surface plasmon resonance sensorgram showing the binding kinetics for human ACE2 and immobilized 2019-nCoV S. Data are shown as black lines, and the best fit of the data to a 1:1 binding model is shown in red. (B) Negative-stain EM 2D class averages of 2019-nCoV S bound by ACE2. Averages have been rotated so that ACE2 is positioned above the 2019-nCoV S protein with respect to the viral membrane. A diagram depicting the ACE2-bound 2019-nCoV S protein is shown (right) with ACE2 in blue and S protein protomers colored tan, pink, and green.

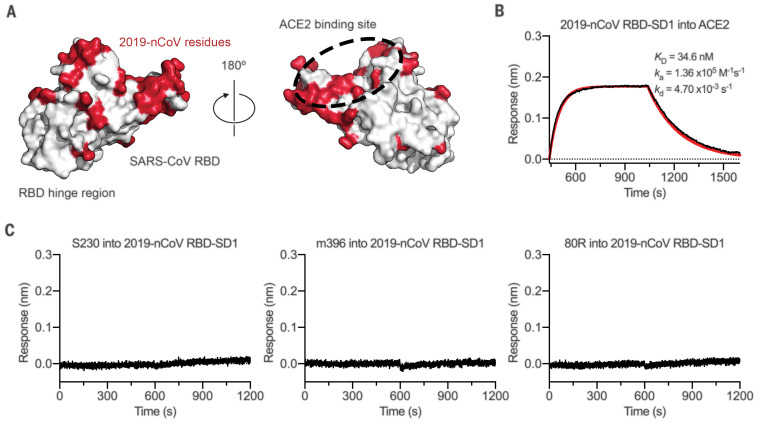

The overall structural homology and shared receptor usage between SARS-CoV S and 2019-nCoV S prompted us to test published SARS-CoV RBD-directed monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for cross-reactivity to the 2019-nCoV RBD (Fig. 4A). A 2019-nCoV RBD-SD1 fragment (S residues 319 to 591) was recombinantly expressed, and appropriate folding of this construct was validated by measuring ACE2 binding using biolayer interferometry (BLI) (Fig. 4B). Cross-reactivity of the SARS-CoV RBD-directed mAbs S230, m396, and 80R was then evaluated by BLI (12, 29–31). Despite the relatively high degree of structural homology between the 2019-nCoV RBD and the SARS-CoV RBD, no binding to the 2019-nCoV RBD could be detected for any of the three mAbs at the concentration tested (1 μM) (Fig. 4C), in contrast to the strong binding that we observed to the SARS-CoV RBD (fig. S8). Although the epitopes of these three antibodies represent a relatively small percentage of the surface area of the 2019-nCoV RBD, the lack of observed binding suggests that SARS-directed mAbs will not necessarily be cross-reactive and that future antibody isolation and therapeutic design efforts will benefit from using 2019-nCoV S proteins as probes.

Fig. 4. Antigenicity of the 2019-nCoV RBD.

(A) SARS-CoV RBD shown as a white molecular surface (PDB ID: 2AJF), with residues that vary in the 2019-nCoV RBD colored red. The ACE2-binding site is outlined with a black dashed line. (B) Biolayer interferometry sensorgram showing binding to ACE2 by the 2019-nCoV RBD-SD1. Binding data are shown as a black line, and the best fit of the data to a 1:1 binding model is shown in red. (C) Biolayer interferometry to measure cross-reactivity of the SARS-CoV RBD-directed antibodies S230, m396, and 80R. Sensor tips with immobilized antibodies were dipped into wells containing 2019-nCoV RBD-SD1, and the resulting data are shown as a black line.

The rapid global spread of 2019-nCoV, which prompted the PHEIC declaration by WHO, signals the urgent need for coronavirus vaccines and therapeutics. Knowing the atomic-level structure of the 2019-nCoV spike will allow for additional protein-engineering efforts that could improve antigenicity and protein expression for vaccine development. The structural data will also facilitate the evaluation of 2019-nCoV spike mutations that will occur as the virus undergoes genetic drift and help to define whether those residues have surface exposure and map to sites of known antibody epitopes for other coronavirus spike proteins. In addition, the structure provides assurance that the protein produced by this construct is homogeneous and in the prefusion conformation, which should maintain the most neutralization-sensitive epitopes when used as candidate vaccine antigens or B cell probes for isolating neutralizing human mAbs. Furthermore, the atomic-level detail will enable the design and screening of small molecules with fusion-inhibiting potential. This information will support precision vaccine design and the discovery of antiviral therapeutics, accelerating medical countermeasure development.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Ludes-Meyers for assistance with cell transfection, members of the McLellan laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript, and A. Dai from the Sauer Structural Biology Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin for assistance with microscope alignment. Funding: This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grant awarded to J.S.M. (R01-AI127521) and by intramural funding from NIAID to B.S.G. The Sauer Structural Biology Laboratory is supported by the University of Texas College of Natural Sciences and by award RR160023 from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT). Author contributions: D.W. collected and processed cryo-EM data. D.W., N.W., and J.S.M. built and refined the atomic model. N.W. designed and cloned all constructs. D.W., N.W., K.S.C., J.A.G., and O.A. expressed and purified proteins. D.W., J.A.G., and C.-L.H. performed binding studies. B.S.G. and J.S.M. supervised experiments. D.W., B.S.G., and J.S.M. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. Competing interests: N.W., K.S.C., B.S.G., and J.S.M. are inventors on U.S. patent application no. 62/412,703 (“Prefusion Coronavirus Spike Proteins and Their Use”), and D.W., N.W., K.S.C., O.A., B.S.G., and J.S.M. are inventors on U.S. patent application no. 62/972,886 (“2019-nCoV Vaccine”). Data and materials availability: Atomic coordinates and cryo-EM maps of the reported structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 6VSB and in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under accession codes EMD-21374 and EMD-21375. Plasmids are available from B.S.G. under a material transfer agreement with the NIH or from J.S.M. under a material transfer agreement with The University of Texas at Austin.

Supplementary Material

science.sciencemag.org/content/367/6483/1260/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs S1 to S8

Table S1

Movies S1 and S2

MDAR Reproducibility Checklist

References and Notes

- 1.Chan J. F., Yuan S., Kok K.-H., To K. K.-W., Chu H., Yang J., Xing F., Liu J., Yip C. C.-Y., Poon R. W.-S., Tsoi H.-W., Lo S. K.-F., Chan K.-H., Poon V. K.-M., Chan W.-M., Ip J. D., Cai J.-P., Cheng V. C.-C., Chen H., Hui C. K.-M., Yuen K.-Y., A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet 395, 514–523 (2020). 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B., Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395, 497–506 (2020). 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N., Bi Y., Ma X., Zhan F., Wang L., Hu T., Zhou H., Hu Z., Zhou W., Zhao L., Chen J., Meng Y., Wang J., Lin Y., Yuan J., Xie Z., Ma J., Liu W. J., Wang D., Xu W., Holmes E. C., Gao G. F., Wu G., Chen W., Shi W., Tan W., Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet S0140-6736(20)30251-8 (2020). 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.-M., Wang W., Song Z.-G., Hu Y., Tao Z.-W., Tian J.-H., Pei Y.-Y., Yuan M.-L., Zhang Y.-L., Dai F.-H., Liu Y., Wang Q.-M., Zheng J.-J., Xu L., Holmes E. C., Zhang Y.-Z., A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L., Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 395, 507–513 (2020). 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., Ren R., Leung K. S. M., Lau E. H. Y., Wong J. Y., Xing X., Xiang N., Wu Y., Li C., Chen Q., Li D., Liu T., Zhao J., Li M., Tu W., Chen C., Jin L., Yang R., Wang Q., Zhou S., Wang R., Liu H., Luo Y., Liu Y., Shao G., Li H., Tao Z., Yang Y., Deng Z., Liu B., Ma Z., Zhang Y., Shi G., Lam T. T. Y., Wu J. T. K., Gao G. F., Cowling B. J., Yang B., Leung G. M., Feng Z., Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. NEJMoa2001316 (2020). 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li F., Structure, Function, and Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol. 3, 237–261 (2016). 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch B. J., van der Zee R., de Haan C. A., Rottier P. J., The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: Structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 77, 8801–8811 (2003). 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8801-8811.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walls A. C., Tortorici M. A., Snijder J., Xiong X., Bosch B.-J., Rey F. A., Veesler D., Tectonic conformational changes of a coronavirus spike glycoprotein promote membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 11157–11162 (2017). 10.1073/pnas.1708727114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gui M., Song W., Zhou H., Xu J., Chen S., Xiang Y., Wang X., Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein reveal a prerequisite conformational state for receptor binding. Cell Res. 27, 119–129 (2017). 10.1038/cr.2016.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pallesen J., Wang N., Corbett K. S., Wrapp D., Kirchdoerfer R. N., Turner H. L., Cottrell C. A., Becker M. M., Wang L., Shi W., Kong W.-P., Andres E. L., Kettenbach A. N., Denison M. R., Chappell J. D., Graham B. S., Ward A. B., McLellan J. S., Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E7348–E7357 (2017). 10.1073/pnas.1707304114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walls A. C., Xiong X., Park Y.-J., Tortorici M. A., Snijder J., Quispe J., Cameroni E., Gopal R., Dai M., Lanzavecchia A., Zambon M., Rey F. A., Corti D., Veesler D., Unexpected receptor functional mimicry elucidates activation of coronavirus fusion. Cell 176, 1026–1039.e15 (2019). 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan Y., Cao D., Zhang Y., Ma J., Qi J., Wang Q., Lu G., Wu Y., Yan J., Shi Y., Zhang X., Gao G. F., Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat. Commun. 8, 15092 (2017). 10.1038/ncomms15092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirchdoerfer R. N., Wang N., Pallesen J., Wrapp D., Turner H. L., Cottrell C. A., Corbett K. S., Graham B. S., McLellan J. S., Ward A. B., Stabilized coronavirus spikes are resistant to conformational changes induced by receptor recognition or proteolysis. Sci. Rep. 8, 15701 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-34171-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Punjani A., Rubinstein J. L., Fleet D. J., Brubaker M. A., cryoSPARC: Algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017). 10.1038/nmeth.4169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wrapp D., McLellan J. S., The 3.1-angstrom cryo-electron microscopy structure of the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus spike protein in the prefusion conformation. J. Virol. 93, e00923-19 (2019). 10.1128/JVI.00923-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walls A. C., Tortorici M. A., Frenz B., Snijder J., Li W., Rey F. A., DiMaio F., Bosch B.-J., Veesler D., Glycan shield and epitope masking of a coronavirus spike protein observed by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 899–905 (2016). 10.1038/nsmb.3293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirchdoerfer R. N., Cottrell C. A., Wang N., Pallesen J., Yassine H. M., Turner H. L., Corbett K. S., Graham B. S., McLellan J. S., Ward A. B., Pre-fusion structure of a human coronavirus spike protein. Nature 531, 118–121 (2016). 10.1038/nature17200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coutard B., Valle C., de Lamballerie X., Canard B., Seidah N. G., Decroly E., The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antiviral Res. 176, 104742 (2020). 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosch B. J., Bartelink W., Rottier P. J., Cathepsin L functionally cleaves the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus class I fusion protein upstream of rather than adjacent to the fusion peptide. J. Virol. 82, 8887–8890 (2008). 10.1128/JVI.00415-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glowacka I., Bertram S., Müller M. A., Allen P., Soilleux E., Pfefferle S., Steffen I., Tsegaye T. S., He Y., Gnirss K., Niemeyer D., Schneider H., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S., Evidence that TMPRSS2 activates the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for membrane fusion and reduces viral control by the humoral immune response. J. Virol. 85, 4122–4134 (2011). 10.1128/JVI.02232-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li W., Moore M. J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S. K., Berne M. A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J. L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T. C., Choe H., Farzan M., Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426, 450–454 (2003). 10.1038/nature02145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belouzard S., Chu V. C., Whittaker G. R., Activation of the SARS coronavirus spike protein via sequential proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5871–5876 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0809524106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J., Lee K. H., Steinhauer D. A., Stevens D. J., Skehel J. J., Wiley D. C., Structure of the hemagglutinin precursor cleavage site, a determinant of influenza pathogenicity and the origin of the labile conformation. Cell 95, 409–417 (1998). 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81771-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.M. Hoffmann, H. Kleine-Weber, N. Krüger, M. Müller, C. Drosten, S. Pöhlmann, The novel coronavirus 2019 (2019-nCoV) uses the SARS-coronavirus receptor ACE2 and the cellular protease TMPRSS2 for entry into target cells. bioRxiv 929042 [Preprint]. 31 January 2020. 10.1101/2020.01.31.929042. [DOI]

- 26.Wan Y., Shang J., Graham R., Baric R. S., Li F., Receptor recognition by novel coronavirus from Wuhan: An analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS. J. Virol. JVI.00127-20 (2020). 10.1128/JVI.00127-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., Chen H.-D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.-D., Liu M.-Q., Chen Y., Shen X.-R., Wang X., Zheng X.-S., Zhao K., Chen Q.-J., Deng F., Liu L.-L., Yan B., Zhan F.-X., Wang Y.-Y., Xiao G.-F., Shi Z.-L., A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature (2020). 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song W., Gui M., Wang X., Xiang Y., Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLOS Pathog. 14, e1007236 (2018). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang W. C., Lin Y., Santelli E., Sui J., Jaroszewski L., Stec B., Farzan M., Marasco W. A., Liddington R. C., Structural basis of neutralization by a human anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome spike protein antibody, 80R. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34610–34616 (2006). 10.1074/jbc.M603275200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prabakaran P., Gan J., Feng Y., Zhu Z., Choudhry V., Xiao X., Ji X., Dimitrov D. S., Structure of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with neutralizing antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15829–15836 (2006). 10.1074/jbc.M600697200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian X., Li C., Huang A., Xia S., Lu S., Shi Z., Lu L., Jiang S., Yang Z., Wu Y., Ying T., Potent binding of 2019 novel coronavirus spike protein by a SARS coronavirus-specific human monoclonal antibody. bioRxiv 9, 382–385 (2020). 10.1080/22221751.2020.1729069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carragher B., Kisseberth N., Kriegman D., Milligan R. A., Potter C. S., Pulokas J., Reilein A., Leginon: An automated system for acquisition of images from vitreous ice specimens. J. Struct. Biol. 132, 33–45 (2000). 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tegunov D., Cramer P., Real-time cryo-electron microscopy data preprocessing with Warp. Nat. Methods 16, 1146–1152 (2019). 10.1038/s41592-019-0580-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramírez-Aportela E., Vilas J. L., Glukhova A., Melero R., Conesa P., Martínez M., Maluenda D., Mota J., Jiménez A., Vargas J., Marabini R., Sexton P. M., Carazo J. M., Sorzano C. O. S., Automatic local resolution-based sharpening of cryo-EM maps. Bioinformatics 36, 765–772 (2020). 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Šali A., Blundell T. L., Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 (1993). 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E., UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004). 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L.-W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C., PHENIX: Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 (2002). 10.1107/S0907444902016657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croll T. I., ISOLDE: A physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 74, 519–530 (2018). 10.1107/S2059798318002425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P., Cowtan K., Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). 10.1107/S0907444904019158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morin A., Eisenbraun B., Key J., Sanschagrin P. C., Timony M. A., Ottaviano M., Sliz P., Collaboration gets the most out of software. eLife 2, e01456 (2013). 10.7554/eLife.01456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grant T., Rohou A., Grigorieff N., cisTEM, user-friendly software for single-particle image processing. eLife 7, e35383 (2018). 10.7554/eLife.35383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

science.sciencemag.org/content/367/6483/1260/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs S1 to S8

Table S1

Movies S1 and S2

MDAR Reproducibility Checklist