Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine the concerns of General Surgery residents as they prepare to be in the frontlines of the response against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19_).

Design, Setting, and Participants

A qualitative study with voluntary dyadic and focus group interviews with a total of 30 General Surgery residents enrolled at 2 academic medical centers in Boston, Massachusetts was conducted between March 12 to 16, 2020.

Results

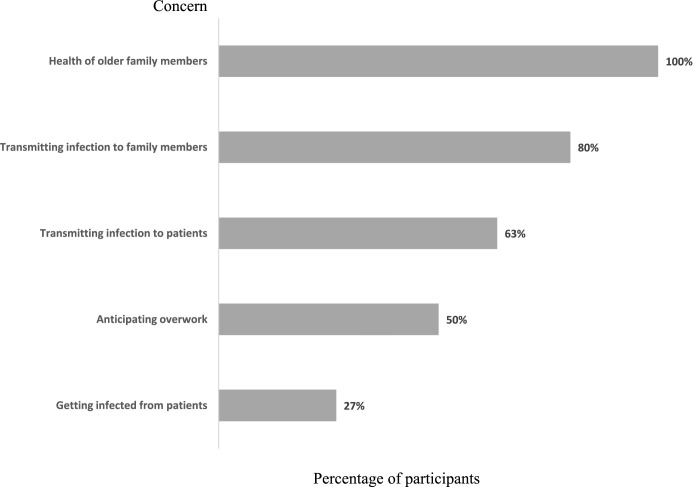

The most commonly reported personal concern related to the COVID-19 outbreak was the health of their family (30 of 30 [100%]), followed by the risk of their transmitting COVID-19 infection to their family members (24 of 30 [80%]); risk of their transmitting COVID-19 infection their patients (19 of 30 [63%]); anticipated overwork for taking care of a high number of patients (15 of 30 [50%]); and risk of their acquiring COVID-19 infection from their patients (8 of 30 [27%]) . The responses were comparable when stratified by sex, resident training level, and residency program. All residents self-expressed their readiness to take care of COVID-19 patients despite the risk of personal or familial harm . To improve their preparedness, they recommend increasing testing capacity, ensuring personal protective equipment availability, and transitioning to a shift schedule in order to minimize exposure risk and prevent burnout.

Conclusions

General Surgery residents are fully dedicated to taking care of patients with COVID-19 infection despite the risk of personal or familial harm. Surgery departments should protect the physical and psychosocial wellbeing of General Surgery residents in order to increase their ability to provide care in the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

KEY WORDS: COVID-19 pandemic, surgical education, surgical workforce, physician wellness

COMPETENCIES: Interpersonal and Communication Skills, Practice-Based Learning and Improvement, Systems-Based Practice

INTRODUCTION

Health care workers are on the frontlines of the response to the global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. They are at a high risk for infection due to direct contact with COVID-19 patients as well as to ongoing shortages of COVID-19 diagnostic tests and personal protective equipment. In China, nearly 3400 health care workers have contracted the virus and at least 22 have died as of February 25, 2020.1

In some countries, the fast-spreading disease has created a severe shortage of health care workers needed to care for an overwhelming influx of patients. Extreme overwork has led to physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion of medical personnel.1 , 2

In China, stress and long hours have been reported to be factors that increase medical personnel susceptibility to COVID-19.1 Furthermore, exhaustion has been linked to cardiac arrest and death in physicians caring for COVID-19 patients.1

Faced with a dramatic shortage of healthcare workers, some affected countries are using any available opportunities to supplement their numbers. China has mobilized tens of thousands of medical workers from all over the country to bolster relief efforts in Wuhan, the epicenter of its COVID-19 outbreak. Italy is recruiting some physicians out of retirement and accelerating the graduation of nursing students still attending school. In England, the government is considering drafting medical students to help deal with the COVID-19 outbreak.

Another measure that has been implemented is included hospital staff reorganization, with all medical personnel being involved in caring for critically ill COVID-19 patients, regardless of their specialty. As the Italian physician Daniele Macchini posted, “there are no more surgeons, urologists, orthopedists, we are only doctors who suddenly become part of a single team to face this tsunami that has overwhelmed us.”3

General Surgery residents are an important component of our nation's healthcare workforce. It is unclear what impact the COVID-19 pandemic will have on this group. As we are in the early phases of this pandemic in the US, we sought to determine the concerns of General Surgery residents as they prepare to be in the frontlines of the response against COVID-19.

METHODS

A qualitative study with voluntary dyadic and focus group interviews conducted between March 12 to 16, 2020 with a total of 30 General Surgery residents enrolled at 2 academic medical centers in Boston, Massachusetts (Boston Medical Center and Brigham and Women's Hospital) and rotating at the VA Boston Healthcare System.

The interview questions were generated through focus group discussions with 5 general surgery residents and 2 attending general surgeons. Subsequently, 2 pilot interviews were conducted with 2 general surgery residents.

All participants were approached in person, via email, or by phone and provided informed oral consent to take part in the study. Residents were told that their participation is voluntary, and that choosing not to participate in the interview will not affect their performance evaluations. Residents were also ensured that their answers will remain confidential. No resident approached declined to participate, and no incentives were provided for participation. Interviews were conducted and recorded by 2 general surgery residents. No repeat interviews were conducted. Personal identifiers were not recorded. All the data were collected in accordance with the requirements of our Institutional Review Board after an exemption status was obtained. The interview technique was open-ended with follow-up questions related to the participants’ answers and responses.

Participants were asked the following 2 questions:

-

1.

What are your main concerns related to the COVID-19 outbreak?

-

2.

What would you recommend for improving resident preparedness for COVID-19 emergency response?

Responses were independently coded, and the resulting nominal data are presented as percentage of responses per category. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to compare ordinal scale variables. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

All 30 invited general surgery residents participated in the interview sessions, representing both genders (36.7% females; 63.3% males) and all 5 clinical postgraduate years (1[33.3%]; 2[20.0%]; 3[16.74%]; 4[20.0%]; and 5[10.0%]).

The most commonly reported personal concern related to the COVID-19 outbreak was the health of their family (30 of 30 [100%]), followed by the risk of their transmitting COVID-19 infection to their family members (24 of 30 [80%]); risk of their transmitting COVID-19 infection their patients (19 of 30 [63%]); anticipated overwork for taking care of a high number of patients (15 of 30 [50%]); and risk of their acquiring COVID-19 infection from their patients (8 of 30 [27%]) ( Fig. 1). The responses were comparable when stratified by sex, resident training level, and residency program.

FIGURE 1.

Surgery residents’ personal concerns related to COVID-19 outbreak.

Although we did not ask our participants about their level of professional commitment to patient care during this pandemic, all residents self-expressed their readiness to take care of COVID-19 patients despite the risk of personal or familial harm. Their recommendations for preparedness for the response to the influx of COVID-19 patients were to increase testing capacity, ensure adequate personal protective equipment availability, and transition to a shift schedule in order to minimize exposure risk and prevent burnout.

DISCUSSION

Our interviews with the General Surgery residents show that they are ready to take all necessary measures to fulfill their duties to protect the public health in a time of crisis, even if they are at increased risk for acquiring COVID-19 infection. Surgical educators, as well as our society at large, should be proud that we are training committed physicians that prioritize patient well-being over their own wellness. However, physicians who are dedicating their lives to helping others should receive the support that they deserve, especially in a time of deep crisis.

The biggest personal concern of our interviewed General Surgery residents was the health of their family members and risk of family transmission. Indeed, Adams and Walls,4 recognize the need to address the health care workers’ anxiety about the well-being of their families. They suggest evaluating the feasibility of health care workers’ family members receiving priority for diagnostic testing, vaccination, and treatment. These measures would be challenging in the current U.S. healthcare climate, given limited testing capacity and lack of vaccines or specific therapies. Clear and supportive conversations about home preparation to minimize family transmission are important to reduce the anxiety of health care workers.4

Our study participants reported that they would welcome an increased availability of COVID-19 testing and personal protective equipment, as well as a transition to a shift schedule in which the minimum necessary number of residents are on clinical duty at any given time, in order to minimize their exposure in the early phases of the pandemic as well as prevent resident burnout. A rotating shift schedule would allow exposed residents periods of self-quarantine without compromising patient care. In later phases of the pandemic, a shift schedule would allow residents infected with COVID-19 to recuperate without risking patient transmission. Indeed, many residency programs in Boston have moved toward a shift-based schedule, in which residents work for 1 to 2 weeks and then are rotated off for the same amount of time. Residents are discouraged from interacting with off-rotation residents to reduce the amount of resident-resident transmission.

In reviewing lessons learned from previous global epidemics, the World Health Organization recommends risk communication with health care workers as a crucial part of the response plan during the stages of preparedness, response, and recovery.5 As recommendations during outbreaks are rapidly evolving, risk communication should be personal, face-to-face when possible, fair, and should promote a no-blame culture.5

As the residents participating in our interviews are preparing for the emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic, they are also reported concerns about overwork and burnout. Fatigue and psychosocial stress are among the most common risks to the safety and health of medical personnel in emergencies. World Health Organization recommendations for preventing and reducing fatigue include delegation of responsibilities, support services, contingency planning for incident mobilization, work hours limitations, and establishment of shift rotations and rest periods.5 , 6

Healthcare institutions should also create professional psychological support systems to provide their workers first aid for acute stress.5 Crisis hotlines have proved very useful for the psychological support of health care workers during the COVID-19 outbreak in China.7 It is very important to continue specialized counseling and professional psychological support even after the crisis, as experience from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome epidemics shows that healthcare workers are at high risk for post-traumatic stress disorder.8 , 9

Our study is not without limitations. First, the small number of participating residents and residency programs could limit the ability to generalize our findings. However, the total number of participating residents is within the range of sample sizes for other resident education studies in the surgical literature. Interviewing a larger group of chief residents from residency programs across the country would be an important next step in generalizing and validating the findings of our study. Second, it is possible that responses to the interview questions may include professional desirability and conformity bias, as residents may have been inclined to provide professionally acceptable responses. By having resident peers conducting the interviews we hoped to minimize the risk of conformity bias. Third, in our study we did not collect participant personal data, such as marital status, living conditions, childbearing responsibilities, and care of their elderly parents. This would have allowed for a better analysis and understanding of our participants’ perspectives.

Even with these limitations, we believe our findings provide meaningful insights into the concerns of general surgery residents during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings should stimulate further discussions by surgical educators and healthcare institutions to identify optimal solutions for improving workforce preparedness for the COVID-19 emergency response.

CONCLUSIONS

General Surgery residents are fully dedicated to taking care of patients with COVID-19 infection, even altruistically accepting the work-related risks to their health. Surgery departments should support their trainees during all phases of the emergency response. Protecting the physical and psychosocial wellbeing of General Surgery residents will increase their ability to provide care in the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Su A. Doctors and nurses fighting coronavirus in China die of both infection and fatigue. LA time. 2020 https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-02-25/doctors-fighting-coronavirus-in-china-die-of-both-infection-and-fatigue Available at. Accessed March 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jankowicz M. An Italian coronavirus nurse posted a picture of her face bruised from wearing a mask to highlight how much health workers are struggling. MSN. 2020 https://www.msn.com/en-us/health/health-news/an-italian-coronavirus-nurse-posted-a-picture-of-her-face-bruised-from-wearing-a-mask-to-highlight-how-much-health-workers-are-struggling/ar-BB115QWS Available at: Accessed March 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Available at: https://www.ecodibergamo.it/stories/bergamo-citta/con-le-nostre-azioni-influenziamola-vita-e-la-morte-di-molte-persone_1344030_11/. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- 4.Adams J.G., Walls R.M. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972. Published online March 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization and International Labour Organization; Geneva: 2017. Occupational Health and Safety of Health Workers, Emergency Responders and Other Workers in Public Health Emergencies: A Manual for Protecting Health Workers and Responders. Licence: CC BYNC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadeghi NB, Wen LS. Novel coronavirus should prompt examination of impact of outbreaks on health care workers. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200214.587257/full/. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- 7.Kwai I. The New York Times; 2020. For China's Overwhelmed Doctors, an Understanding Voice Across the Ocean.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/23/world/asia/china-coronavirus-hotline.html Available at: Accessed March 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu P., Fang Y., Guan Z. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:302–311. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sim K., Chua H.C. The psychological impact of SARS: a matter of heart and mind. CMAJ. 2004;170:811–812. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1032003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]