Abstract

Objective

Here, we re-examine TOMM40-523′ as a race/ethnicity-specific risk modifier for late-onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD) with adjustment for local genomic ancestry (LGA) in Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 haplotypes.

Methods

The TOMM40-523′ size was determined by fragment analysis and whole genome sequencing in homozygous APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 haplotypes of African (AF) or European (EUR) ancestry. The risk for LOAD was assessed within groups by allele size.

Results

The TOMM40-523′ length did not modify risk for LOAD in APOE ε4 haplotypes with EUR or AF LGA. Increasing length of TOMM40-523′ was associated with a significantly reduced risk for LOAD in EUR APOE ε3 haplotypes.

Conclusions

Adjustment for LGA confirms that TOMM40-523′ cannot explain the strong differential risk for LOAD between APOE ε4 with EUR and AF LGA. Our study does confirm previous reports that increasing allele length of the TOMM40-523′ repeat is associated with decreased risk for LOAD in carriers of homozygous APOE ε3 alleles and demonstrates that this effect is occurring in those individuals with the EUR LGA APOE ε3 allele haplotype.

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) has long been the strongest and most consistently identified gene associated with the risk for developing late-onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD).1,2 Of interest, the APOE ε4 allele in AFs and African Americans confers a much lower risk for disease than the identical allele in Europeans (EUR).3–5 It was recently discovered that this racial difference can be attributed to the local genetic ancestry (LGA) within the APOE haplotype.6 The responsible “protective” locus within the APOE LGA remains unknown, however. TOMM40 is a gene lying within the APOE haplotype that codes for a channel-forming subunit required for protein import into mitochondria. It contains an intronic poly-T repeat known as “TOMM40-523′,” which varies in length by individual and race/ethnicity. The TOMM40-523′ length has been proposed to influence the transcription of APOE and thus modify the risk for LOAD,7–13 although the significance of its association with LOAD remains controversial.14–19 The TOMM40-523′ LOAD relationship has been analyzed by race in the context of global genetic ancestry but not by using adjustment for LGA within the TOMM40-APOE haplotype, allowing for misclassification, given sometimes common differences between LGA and global ancestry.6

To confirm whether varying sizes of the TOMM40-523′ allele can truly explain the reduced risk for LOAD in African Americans expressing the APOE ε4 allele, we re-examine TOMM40-523′ with adjustment for LGA. We further investigate racial differences in effect of TOMM40-523′ on APOE ε3 carriers.

Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

All ascertainment activities were approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) at the respective universities and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained for all participants. The current study is approved by the University of Miami IRB.

Samples and ascertainment

DNA samples used for this study were part of a larger study of Alzheimer disease (AD) genetics and were ascertained at Case Western University, Wake Forest University, and the University of Miami between 2012 and 2019. Participants were selected if they were homozygous for either the APOE ε3 or APOE ε4 allele, eliminating the need to phase TOMM40-523′ alleles by haplotype. All participants were enrolled under a standard ascertainment protocol. As part of this protocol, sociodemographic and clinical historic data were obtained for all participants. This included demographic variables, diagnosis, age at onset for cases, method of diagnosis, history of illness, and the presence of other relevant comorbidities. The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale,20,21 National Institute on Aging (NIA)-Late Onset Alzheimer's Disease cognitive battery,22,23 and Mini-Mental State Exam24 or the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam25 readings were collected for all participants.

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnosis was made via case conferences of all clinical, historical, and psychometric test data (e.g., laboratory tests, neurologic examination, neuroimaging, and neuropsychological screening and testing) by a multidisciplinary clinical adjudication panel consisting of a boarded neurologist (J.M.V.), neuropsychologist (M.L.C.), and clinical staff (P.R.M.). All individuals with AD met the internationally recognized standard National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke - Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association26 or updated NIA-Alzheimer's Association criteria and were further classified as definite (neuropathologic confirmation), probable, or possible AD.27

Individuals classified as unaffected controls were older than 65 years of age, cognitively normal on the NIA-Late Onset Alzheimer's Disease battery, and had a CDR of zero. The controls were matched to cases for age, sex, and ethnicity.

APOE genotyping and determination of local genetic ancestry genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping was performed using 3 different platforms: Expanded Multi-Ethnic Genotyping Array, Illumina 1Mduo (v3), and the Global Screening Array (Illumina, San Diego, CA). APOE genotyping was conducted as in Saunders et al.28 Quality control analyses were executed using the PLINK software, v.2.29 The samples with call rates less than 90% and with excess or insufficient heterozygosity (±3 SDs) were excluded. Sex concordance was checked using X chromosome data. To eliminate duplicate and related samples, relatedness among the samples was estimated using identity by descent. SNPs were eliminated from further analysis if they were present in samples with call rates less than 97%, had minor allele frequencies less than 0.01, or were not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p < 1.e−5).30

Genotyping data were initially phased using the SHAPEIT tool ver.2 to identify local ancestry at the TOMM40-APOE haplotype.31 The discriminative RFMix modeling approach was used to estimate the genetic ancestral background (AF vs EUR) at the region of interest.32 The Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) data were used as the reference panel in the analysis.33

Genotyping of TOMM40-523′ allele using fragment analysis

The TOMM40-523′ poly-T repeat was first PCR-amplified using fluorescein amidite-labeled forward primer 5′–CCTCCAAAGCATTGGGATTA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GATTCCTCACAACCCCAAGA-3′. PCR was performed using Taq polymerase in the presence of 4% DMSO with a final volume of 25 uL. PCR conditions were as follows: initial 6-minute denaturation at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 54°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 40 seconds. Final extension was performed for 10 minutes at 72°C. PCR products underwent subsequent fragment analysis with LIZ600 size standard using 3130xl Genetic Analyzer, and resolved fragments were visualized with GeneMapper v4.0 (Applied Biosystems Inc., CA).

The allele size was determined by subtracting the fragment analysis-determined size by 439, the number of base pairs surrounding each end of the poly-T stretch in our PCR product. The mode of each peak was selected and established as the “true” poly-T length (figure e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A230). In cases where the mode was shared by 2 peaks, the mean length of the 2 peaks was used. In all cases, peak size was rounded to the nearest integer. A replicate fragment analysis was performed on 20 randomly selected samples to ensure consistency in length calls. A fluorescein amidite-labeled PCR fragment with known length and void of repeated sequences was run alongside samples to ensure accurate sizing.

Genotyping of TOMM40-523′ using Whole Genome Sequencing

To test whether whole genome sequencing (WGS) could be used to genotype the TOMM40-523′ repeat, WGS was performed on a subset of 15 samples using a PCR-free library preparation and paired-end 150bp sequencing on the Illumina Novaseq. Raw reads were aligned to the human reference genome GRCh38 using the Burrows-Wheeler transform alignment algorithm.34 Resulting Binary Alignment Map files were visualized in the Integrative Genomics Viewer,35 and the number of thymine bases at rs10524523 were calculated and compared with fragment analysis of the same set of samples.

Statistical analysis

TOMM40-523′ poly-T lengths were first binned into short (<20 T's), long (20–29T's), and very long (≥30 T's) alleles, as originally defined.18 To assess the effect of the TOMM40-523′ poly-T length on LOAD risk, we stratified our data set according to local ancestries (AF and EUR) and APOE alleles (ε3 and ε4). Next, we categorized the counts of individuals in our data set by length of TOMM40-523′ poly-T (short, long, and very long) and affection status (affected vs control). We applied the Fisher exact test on each subgroup to test the significance of a difference between the proportions in the length of TOMM40-523′ poly-T and affection status (short vs long, short vs very long, and short vs sum of long and very long).

Data availability

Any data pertaining to this article and not published within this article is publicly available and may be requested through collaboration.

Results

Descriptive statistics

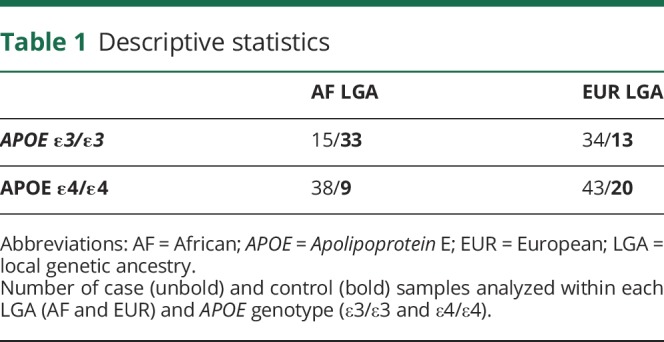

A total of 205 samples composed of 75 controls and 130 cases were analyzed, making up 410 individual haplotypes. Within AF LGA samples, 48 were APOE ε3/ε3 (15 cases, 33 controls) and 47 were APOE ε4/ε4 (38 cases, 9 controls). Within EUR LGA samples, 47 were APOE ε3/ε3 (34 cases, 13 controls) and 63 were APOE ε4/ε4 (43 cases, 20 controls) (table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

The average age at onset for affected individuals was 71.3 years old (SD = 8.1 years). The average age of examination for controls was 73.0 year old (SD = 6.9 years). Affected and control groups consisted of 70.8% and 65.3% women, respectively. The entirety of each haplotype was either EUR LGA or AF LGA, with zero samples expressing mixed LGA. Within affected individuals, 56.0% of haplotypes exhibited AF LGA. 40.8% of control haplotypes contained AF LGA.

Genotyping

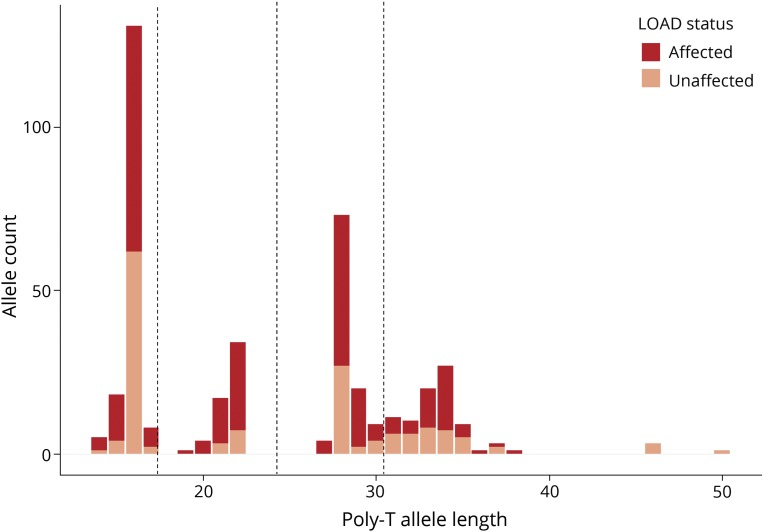

Polymerase stutter for the TOMM40-523′ allele, as described in previous TOMM40 studies,18 was observed with an average of 4 peaks per allele (figure e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A230). There was 100% congruence of peaks between replicate samples. The length standard was consistently found to be 4bp shorter than its known value. To correct for this discrepancy, 4bp were added to poly-T allele lengths of each sample. Comparable with previous study,36 our allele sizes appeared to distribute within 4 separate bins rather than the traditionally used 3 bin sizes (figure 1). For completeness, we also performed a similar 4-bin analysis in which the allele sizes were binned into very small (≤22 T's), small (23–28 T's), long (29–34 T's), and very long (≥35 T's). Allele comparisons made can be seen in table e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A231.

Figure 1. Distribution of TOMM40-523′ allele sizes across all samples.

Allele count (y-axis) assigned to respective poly-T allele lengths (x-axis) for both cases (dark red) and controls (light red). The dotted lines delineate the 4 bin sizes used in the four bin analysis. LOAD = late-onset Alzheimer disease.

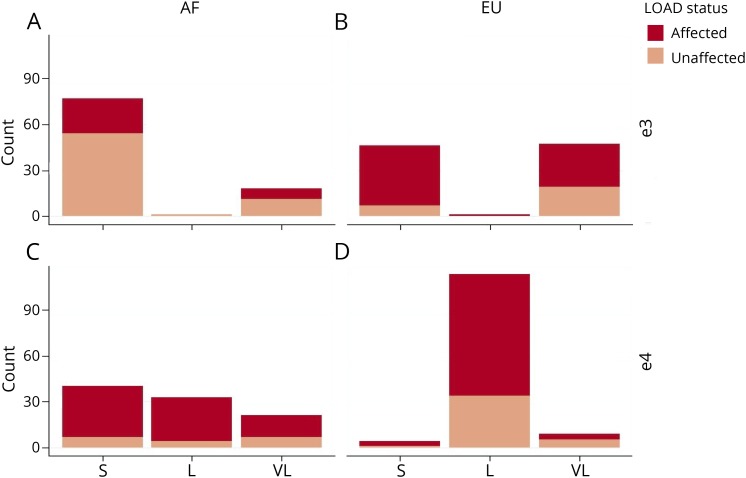

Allele frequencies differ by ancestry and APOE status

Allele frequencies varied between haplotypes harboring EUR vs AF ancestry and APOE ε3 vs APOE ε4 alleles (figure 2). AF LGA was more than 2 times more likely to display short (S) alleles compared with EUR LGA (148 vs 70). Long (L) alleles were commonly observed in APOE ε4 (123 alleles) but not APOE ε3 (24 alleles) haplotypes. AF APOE ε4 haplotypes exhibited the most variance in allele size, and EUR APOE ε4 contained more long (L) alleles than any other haplotype.

Figure 2. TOMM40-523′ allele frequencies.

TOMM40-523′ allele frequencies in AF APOE ε3 (A), AF APOE ε4 (C), EUR APOE ε3 (B), and AF APOE ε3 (D) haplotypes for both cases (dark red) and controls (light red). AF = African; APOE = Apolipoprotein E; EUR = European; L = long; LGA = local genetic ancestry; LOAD = late-onset Alzheimer disease; S = short; VL = very long.

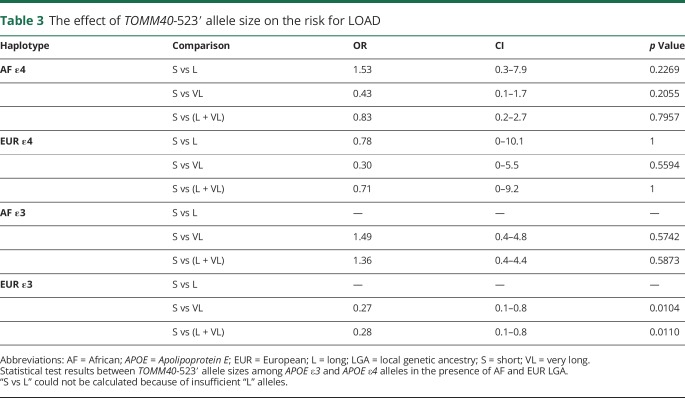

Effect of TOMM40-523′ length on risk for LOAD

There was no significant difference in risk for LOAD between “S” and “L” alleles, “S” and “very long (VL)” alleles, or “S” and “L + VL” alleles in the APOE ε4 haplotypes with AF (p = 0.2269, 0.2055, 0.7957, respectively) or EUR (p = 1, 0.9954, 1, respectively) LGA. However, there was a significant effect of TOMM40-523′ allele size within APOE ε3 haplotypes of EUR LGA. Both “VL” and “VL + L” allele groups had reduced risk compared with haplotypes with an “S” allele (VL: p = 0.0104) (VL + L: p = 0.011) (table 2). Our 4-bin analysis (VS, S, L, and VL) results were congruent with those of our 3-bin analysis (table e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A231).

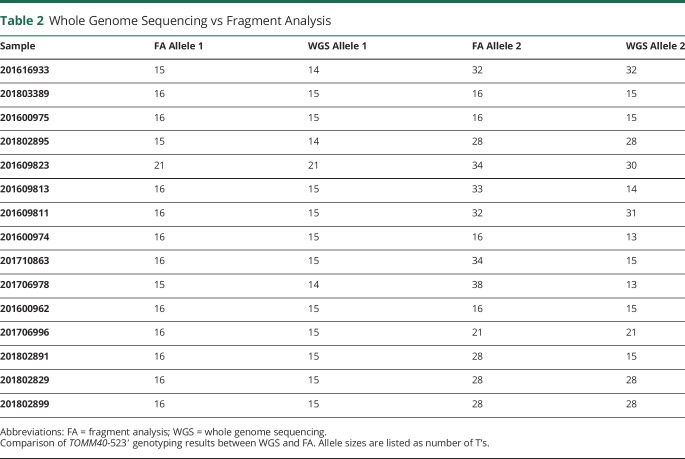

Table 2.

Whole Genome Sequencing vs Fragment Analysis

Genotyping TOMM40-523′ with WGS

Fifteen samples were genotyped using WGS. Their allele sizes, compared with the allele sizes determined via fragment analysis, can be seen in table 3. The correlations were calculated using fragment analysis as the reference length. The 2 methods correlated well for alleles <20 bp in length (R2 = 0.95), though correlation decreased with inclusion of “L” (R2 = 0.85) and “VL” (R2 = 0.57) allele sizes.

Table 3.

The effect of TOMM40-523′ allele size on the risk for LOAD

Discussion

This TOMM40-523′ LOAD association study adjusted for local rather than global genetic ancestry, eliminating the potential for misclassification of ancestry housed within the TOMM40-523′ locus. This is an important distinction which cannot be overlooked. After re-examination of the TOMM40-523′ allele with adjustment for LGA, our study found no significant effect of the TOMM40-523′ poly-T size on the risk for LOAD within APOE ε4 haplotypes. This suggests that the TOMM40-523′ allele cannot explain the strong difference in risk conferred by the APOE ε4 allele between AF and EUR carriers of APOE ε4. A larger sample size is needed to test any possible weak to moderate significant differences, although given the current p-values, this seems unlikely. Therefore, we suggest that future efforts to explain the large risk difference between AFs and non-Hispanic whites should be directed toward the investigation of other candidate regions within the APOE haplotype to identify the protective variant for APOE ε4 found in the AF LGA.

Of interest, we did find a significant relationship between the poly-T length and risk for LOAD in APOE ε3 alleles harboring EUR LGA. The increasing number of T's was associated with decreased risk for LOAD. Our findings validate the findings of 2 previous studies reporting a significant under-representation of VL-APOE ε3 haplotypes in the LOAD cases vs controls36 and significantly fewer VL alleles in EUR LOAD patients vs controls.37 This suggests that the TOMM40-523′ variant may indeed play a role in modifying risk for disease in this subpopulation of APOE ε3 carriers. Given the tendency for human genomic repeats to have a negative phenotypic effect as they increase in length,38,39 the finding that the largest expansion of the TOMM40-523′ repeat is protective is unusual at first glance. Our results align biologically in the case of the TOMM40-523′ repeat; however, as studies have shown that the expression of TOMM40 increases with size of TOMM40-523′ poly-T repeat11–13 and that augmented TOMM40 expression confers subsequent mitochondrial protection.11 TOMM40-523′ has additionally been identified as a transcriptional start site by the FANTOM project.40 It is also possible, and perhaps likely, that the TOMM40-523′ repeat is a tagging variant for a distinct protective factor which is APOE ε3 specific. Stratifying risk within patients carrying APOE ε3 on a EUR LGA, most non-Hispanic white patients, could be important in the clinical setting and perhaps in clinical trials. Further molecular experiments in inducible pluripotent stem cell lines with APOE ε3/ε3 possessing EUR LGA could deepen our understanding of this association and provide clues regarding LOAD pathophysiology.

Our study further used WGS to genotype the TOMM40-523′ allele. Genotyping long microsatellite regions such as TOMM40-523′ can be challenging. Current methods used to size poly-T and poly-A tracts such as TOMM40-523′ within the human genome include fragment analysis and Sanger sequencing.14 Although our WGS data correlated extremely well with “S” TOMM40-523′ alleles, it grew less consistent with the inclusion of “L” and “VL” alleles. This is undoubtedly because of the shorter size fragments used in Illumina WGS. Long fragment WGS would likely increase the concordance to fragment analysis. Repetitive DNA regions are likely to gain importance in examining the risk for disease and use of WGS to assess these regions and may play a progressively large role.

As noted, there were very few “L” alleles within the APOE ε3 haplotypes. Because of this, we were unable to generate proper odds ratios for “S” vs “L” alleles in this subgroup. It was additionally difficult to obtain the AF LGA APOE ε4/ε4 control samples. Although we improved on previous study designs by adjusting for LGA, our reduced sample size, as compared to previous studies,16,36 may have limited the resolution within groups.

In our study, the TOMM40-523′ poly-T variant could not explain the large difference in the risk for LOAD between AF and EUR LGA on the APOE ε4 haplotype. Increasing TOMM40-523′ length on the APOE ε3 haplotype may decrease the risk for LOAD and warrants further investigation. The differential effect of LGA in APOE ε4, and now shown in APOE ε3, is continuing the examples of the importance of considering LGA while interpreting the risk for disease. In the setting of personalized medicine, identical genetic variants do not always confer equal risk. Rather, genetic loci must be examined with an understanding of their contextual ancestry. As we increase the amount of diversity in our genetic studies, this is likely to become a common cofactor in assessing risk.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the families and community members who graciously agreed to participate in the study and made this research possible.

Glossary

- AF

African

- APOE

Apolipoprotein E

- EUR

European

- IRB

institutional review board

- LOAD

late-onset Alzheimer disease

- LGA

local genomic ancestry

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- WGS

whole genome sequencing

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

This work was supported by the NIH [RF1-AG059018, R01-AG028786, RF1-AG054074, U01-AG052410], the Alzheimer's Association [Zenith Award, ZEN-19-591586], and the BrightFocus Foundation [A2018425S].

Disclosure

The authors have no competing interests to declare. Go to Neurology.org/NG for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL. Alzheimer's disease. In: King RA, Rotter JI, eds. The Genetic Basis of Common Diseases. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2002:818–830. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michaelson DM. Apoe ε4: the most prevalent yet understudied risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Demen 2014;10:861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, et al. The APOE-∊ 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, Whites, and Hispanics. JAMA 1998;279:751–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendizabal I, Sandoval K, Berniell-Lee G, et al. Genetic origin, admixture, and asymmetry in maternal and paternal human lineages in Cuba. BMC Evol Biol 2008;8:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohara T, Ninomiya T, Hirakawa Y, et al. Association study of susceptibility genes for lateonset Alzheimer's disease in the Japanese population. Psychiatr Genet 2012;22:290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajabli F, Feliciano BE, Celis K, et al. Ancestral origin of APOE ε4 Alzheimer disease risk in Puerto Rican and African American populations. PLoS Genet 2018;14:e1007791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linnertz C, Saunders AM, Lutz MW, et al. Characterization of the poly-T variant in the TOMM40 gene in diverse populations. PLoS One 2012;7:e30994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roses AD, Lutz MW, Saunders AM, et al. African-American TOMM40'523-APOE haplotypes are admixture of West African and Caucasian alleles. Alzheimer's Demen 2014;10:592–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu L, Lutz MW, Wilson RS, et al. APOE ε4-TOMM40 ‘523 haplotypes and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in older Caucasian and African Americans. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura A, Nonomura H, Tanaka S, et al. Characterization of APOE and TOMM40 allele frequencies in the Japanese population. Alzheimer Dement 2017;3:524–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeitlow K, Charlambous L, Ng I, et al. The biological foundation of the genetic association of TOMM40 with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017;1863:2973–2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payton A, Sindrewicz P, Pessoa V, et al. A TOMM40 poly-T variant modulates gene expression and is associated with vocabulary ability and decline in nonpathologic aging. Neurobiol Aging 2016;39:217.e1–217.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linnertz C, Anderson L, Gottschalk W, et al. The cis-regulatory effect of an Alzheimer's disease-associated poly-T locus on expression of TOMM40 and apolipoprotein E genes. Alzheimer's Demen 2014;10:541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiba-Falek O, Gottschalk WK, Lutz MW. The effects of the TOMM40 poly-T alleles on Alzheimer's disease phenotypes. Alzheimer's Demen 2018;14:692–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roses AD, Lutz MW, Crenshaw DG, Grossman I, Saunders AM, Gottschalk WK. TOMM40 and APOE: requirements for replication studies of association with age of disease onset and enrichment of a clinical trial. Alzheimer's Demen 2013;9:132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jun G, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, et al. Comprehensive search for Alzheimer disease susceptibility loci in the APOE region. Arch Neurol 2012;69:1270–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutz MW, Crenshaw DG, Saunders AM, Roses AD. Genetic variation at a single locus and age of onset for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Demen 2010;6:122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roses A, Lutz MW, Amrine-Madsen H, et al. A TOMM40 variable-length polymorphism predicts the age of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Pharmacogenomics J 2010;10:375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caselli RJ, Saunders A, Lutz M, Huentelman M, Reiman E, Roses A. TOMM40, APOE, and age of onset of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Dement 2010;6:S202. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger W, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982;140:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The uniform data set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from alzheimer disease centers. Alzheimer Dis Associated Disord 2006;20:210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer's disease centers' uniform data set (UDS): the neuropsychological test battery. Alzheimer Dis associated Disord 2009;23:91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) Examination. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;41:114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA work group* under the auspices of department of Health and human Services Task Force on alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1984;34:939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Demen 2011;7:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saunders AM, Hulette C, Welsh-Bohmer KA, et al. Specificity, sensitivity, and predictive value of apolipoprotein-E genotyping for sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 1996;348:90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:559–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson CA, Pettersson FH, Clarke GM, Cardon LR, Morris AP, Zondervan KT. Data quality control in genetic case-control association studies. Nat Protoc 2010;5:1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delaneau O, Marchini J, McVean GA, et al. Integrating sequence and array data to create an improved 1000 Genomes Project haplotype reference panel. Nature Commun 2014;5:3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maples BK, Gravel S, Kenny EE, Bustamante CD. RFMix: a discriminative modeling approach for rapid and robust local-ancestry inference. Am J Hum Genet 2013;93:278–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cann HM, De Toma C, Cazes L, et al. A human genome diversity cell line panel. Science 2002;296:261–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009;25:1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 2011;29:24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maruszak A, Pepłońska B, Safranow K, Chodakowska-Żebrowska M, Barcikowska M, Żekanowski C. TOMM40 rs10524523 polymorphism's role in late-onset Alzheimer's disease and in longevity. J Alzheimer's Dis 2012;28:309–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cruchaga C, Nowotny P, Kauwe JS, et al. Association and expression analyses with SNPs in TOMM40 in Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol 2011;68:1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beyer K, Humbert J, Ferrer A, et al. A variable poly‐T sequence modulates α‐synuclein isoform expression and is associated with aging. J Neurosci Res 2007;85:1538–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutherland GR, Richards RI. Simple tandem DNA repeats and human genetic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1995;92:3636–3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bessiere C, Saraswat M, Grapotte M, et al. Sequence-level instructions direct transcription at polyT short tandem repeats. bioRxiv 2019:634261. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any data pertaining to this article and not published within this article is publicly available and may be requested through collaboration.