Abstract

Background

Nutritional rickets is a disease which affects children, especially in low‐ and middle‐income countries. It causes problems such as skeletal deformities and impaired growth. The most common cause of nutritional rickets is vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D administered with or without calcium is commonly regarded as the mainstay of treatment. In some sunny countries, however, where children are believed to have adequate vitamin D production from exposure to ultraviolet light, but who are deficient in calcium due to low dietary intake, calcium alone has also been used in the treatment of nutritional rickets. Therefore, it is important to compare the effects of vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children living in different settings.

Objectives

To assess the effects of vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, LILACS, WHO ICTRP Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov. The date of the last search of all databases was 25 July 2019. We applied no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCT) involving children aged 0 to 18 years with nutritional rickets which compared treatment with vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened the title and abstracts of all studies, extracted data and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. We resolved any disagreements by consensus or recourse to a third review author. We conducted meta‐analyses for the outcomes reported by study authors. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) and, for continuous outcomes, we calculated mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs. We assessed the certainty of the evidence of the included studies using GRADE.

Main results

We identified 4562 studies; of these, we included four RCTs with 286 participants. The studies compared two or more of the following: vitamin D, calcium or vitamin D plus calcium. The number of participants randomised to receive vitamin D was 64, calcium was 102 and vitamin D plus calcium was 120. Two studies were conducted in India and two were conducted in Nigeria. None of the included studies had a low risk of bias in all domains. Three studies had a high risk of bias in at least one domain. The age of the participants ranged between six months and 14 years. The duration of follow‐up ranged between 12 weeks and 24 weeks.

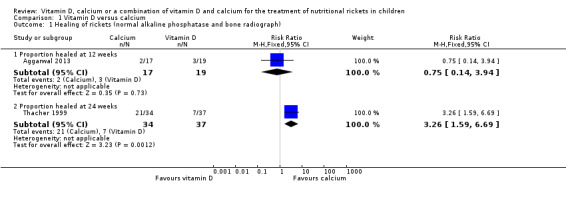

Two studies compared vitamin D to calcium. There is low‐certainty evidence that, at 24 weeks' follow‐up, calcium alone improved the healing of rickets compared to vitamin D alone (RR 3.26, 95% CI 1.59 to 6.69; P = 0.001; 1 study, 71 participants). Comparing vitamin D to calcium showed no firm evidence of an advantage or disadvantage in reducing morbidity (fractures) (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.32; P = 0.23; 1 study, 71 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). Adverse events were not reported.

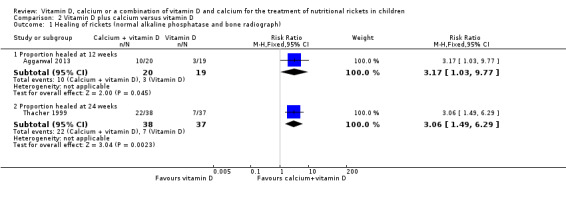

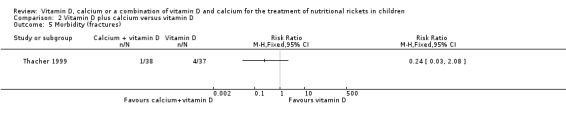

Two studies compared vitamin D plus calcium to vitamin D at 12 or 24 weeks. Vitamin D plus calcium improved healing of rickets compared to vitamin D alone at 24 weeks' follow‐up (RR 3.06, 95% CI 1.49 to 6.29; P = 0.002; 1 study, 75 participants; low‐certainty evidence). There is no conclusive evidence in favour of either intervention for reducing morbidity (fractures) (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.08; P = 0.20; 1 study, 71 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) or adverse events (RR 4.76, 95% CI 0.24 to 93.19; P = 0.30; 1 study, 39 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

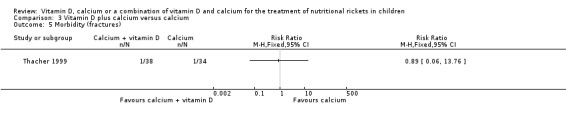

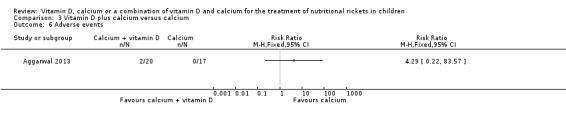

All four included studies compared vitamin D plus calcium to calcium at different follow‐up times. There is no conclusive evidence on whether vitamin D plus calcium in comparison to calcium alone improved healing of rickets at 24 weeks' follow‐up (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.90; P = 0.53; 2 studies, 140 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). Evidence is also inconclusive for morbidity (fractures) (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.06 to 13.76; P = 0.94; 1 study, 72 participants; very low‐certainty evidence) and adverse events (RR 4.29, 0.22 to 83.57; P = 0.34; 1 study, 37 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

Most of the evidence in the review is low or very low certainty due to risk of bias, imprecision or both.

None of the included studies assessed all‐cause mortality, health‐related quality of life or socioeconomic effects. One study assessed growth pattern but this was not measured at the time‐point stipulated in the protocol of our review (one or more years after commencement of therapy).

Authors' conclusions

This review provides low‐certainty evidence that vitamin D plus calcium or calcium alone improve healing in children with nutritional rickets compared to vitamin D alone. We are unable to make conclusions on the effects of the interventions on adverse events or morbidity (fractures).

Plain language summary

Vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children

Review question

To assess the effects of vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children.

Background

Nutritional rickets is a disease of the bones that affects mostly children in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Children with nutritional rickets typically have deformed bones, may not grow well and experience other health problems. A lack of vitamin D is the most common cause of nutritional rickets. As such, nutritional rickets is usually treated by giving the child vitamin D with or without calcium. In some sunny countries, however, calcium alone has been used to treat nutritional rickets in children who are believed to have adequate vitamin D from their exposure to sunlight but who lack adequate calcium in their diet. This review was conducted to find out whether vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium is best for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children.

Study characteristics

We found four randomised controlled trials (clinical trials where people are randomly put into one of two or more treatment groups) that compared vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children. The 286 children in the studies were aged six months to 14 years. Following treatment, the children were monitored for between 12 and 24 weeks.

This evidence is up to date as of 25 July 2019.

Key results

We found evidence that using calcium alone or vitamin D plus calcium to treat nutritional rickets may improve healing when compared to using vitamin D alone. We are uncertain about the effects on fractures of calcium alone compared to vitamin D alone. We are uncertain about the effects on fractures or other side effects of vitamin D plus calcium compared to vitamin D alone. We are uncertain about the effects of vitamin D plus calcium compared to calcium alone on healing of rickets, fractures and side effects.

None of the studies reported on growth pattern (differences in height, weight, height for age, weight for age), death from any cause, socioeconomic effects (cost of treatment, resources lost due to illness or due to absence of the caregiver from work, cost of visits to hospital or health facility) and health‐related quality of life.

Reliability of the evidence

The reliability of the evidence for all the outcomes in our review is low or very low. The reason for the uncertainty is mostly due to the low number of participants in the studies and the low number of studies included in the review. Imprecise results and the potential to arrive at wrong conclusions because of the way the trials were conducted in some of the studies also contributed to the level of uncertainty.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Rickets is a disease of children caused by failure of the growing bone to calcify, leading to skeletal deformities, impaired growth, and other clinical features which vary depending on the age of the child and the stage of the disease. Most children are affected within the first 18 months of life (Pettifor 2004). Rickets is more prevalent among young children in low‐ and middle‐income countries and is a notable cause of deformities in children in Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Asia, the Middle East and parts of southern Europe (Prentice 2008). About 555,000 children in Bangladesh between the ages of one year and 15 years have deformities caused by rickets (UNICEF 2015). Rickets occurs in both dark‐ and light‐skinned children but dark‐skinned children are more commonly affected. Lerch 2007 distinguished three categories of children who are affected: infants with fair skin; infants with intermediate or dark skin living in their indigenous area and infants with intermediate or dark skin living in an area with lower ultraviolet B (UVB) irradiation than in their indigenous area.

Skeletal deformities associated with rickets are the result of delayed or failed mineralisation of the matrix at the growth plates in children before fusion of the epiphyses (Greenbaum 2011). Bowing of legs (genu varum), knock knees (genu valgum), and soft, asymmetrical, deformable skull (craniotabes) are the most common skeletal deformities associated with rickets. Other features include frontal bossing, rachitic rosary of the ribcage (swelling of the costochondral junction of the ribs), enlargement of the wrists and ankles. deformation of the limbs, hypocalcaemic convulsions, chest deformity (pigeon chest) and delayed motor movement (Agarwal 2009; Greenbaum 2011; Ozkan 2010; Weisberg 2004). Bone pain or tenderness in the arms, pelvis, legs or spine; delayed formation of teeth; loss of muscle strength (decreased muscle tone); impaired growth; increased bone fractures; skeletal deformities and abnormal spine curves (kyphosis or scoliosis) are also associated with rickets (Greenbaum 2011). Some skeletal deformities caused by rickets may require corrective surgery, positioning or bracing (Greenbaum 2011).

Vitamin D deficiency is the most common cause of rickets. There are two major types of rickets: calcipenic (hypocalcaemic) rickets and phosphopenic (hypophosphataemic) rickets. Calcipenic rickets is subdivided into nutritional rickets, vitamin D dependent rickets (type I or 1‐alpha‐hydroxylase deficiency; type II or hereditary resistance to vitamin D), and defects in vitamin D absorption or metabolism of calcium or vitamin D. Nutritional rickets may be caused by dietary deficiency of vitamin D, calcium or phosphorus; cases due to deficiency of calcium or phosphorus are less common (Pettifor 2012). Exclusively breastfed infants who do not receive vitamin D supplementation, dark‐skinned infants and infants born to mothers who were vitamin D deficient during pregnancy are most affected (Misra 2008; Pettifor 2004).

Rickets may be diagnosed clinically by physical examination and taking a medical history, and confirmed biochemically or radiographically (Nield 2006). Biochemical findings in rickets include normal or decreased blood levels of calcium; elevated blood levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) or parathyroid hormone; normal, decreased or increased blood levels of phosphate; and decreased blood levels of 25‐hydroxy vitamin D (25‐OHD) in vitamin D deficiency rickets (Pettifor 2005; Shaw 2004; Thacher 2003). Findings from radiographic investigations include cupping, flaring and fraying of the metaphysis, rachitic rosary, and angular deformities of the bones of the arms and legs (Greenbaum 2011; Hochberg 2003).

Although rickets was prevalent in Europe and the USA between the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, the discovery of the antirachitic properties of vitamin D and subsequent fortification of foods with vitamin D led to its eradication in the 1930s (Jessop 1950; Welch 2000). In more recent times, however, there has been a re‐emergence of rickets in these and other industrialised countries (Welch 2000; Wendling 2007). Callaghan 2006 reported an overall incidence of 7.5 cases per 100,000 per year in one survey in 2001 of children under five years of age in the UK (West Midlands). Most of the children were of black African or African‐Caribbean origin. The overall annual incidence rate in Canada in 2004 was 2.9 cases per 100,000.

Studies carried out to assess the prevalence of rickets in Asia and Africa show wide variation of prevalence rates from 42% in Ethiopian to 9% in Nigerian children aged six months to three years (Pfitzner 1988; Prentice 2008). The treatment of rickets depends on the type and cause, and usually includes supplementation with vitamin D, its metabolites, calcium or a combination. Goals of treatment are to relieve symptoms and correct the cause of the condition in order to prevent the disease from returning (Greenbaum 2011).

Description of the intervention

Rickets is treated by administration of vitamin D, calcium or both, or phosphorus depending on the underlying cause. With particular reference to nutritional rickets, vitamin D administered with or without calcium is commonly regarded as the mainstay of treatment (Greenbaum 2011; Reddy 2008). Vitamin D is administered orally or intramuscularly as ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). Various vitamin D preparations, dosages (high versus low), dosing schedules (single versus multiple) and administration routes (oral or intramuscular) are available. Where a child's compliance with a treatment regimen may be difficult, vitamin D may be given as a single administration of 100,000 IU to 600,000 IU over one to five days (high‐dose therapy or 'Stosstherapie', Balasubramanian 2013; Misra 2008; Pettifor 2014a). Adverse events such as hypercalcaemia and hypercalciuria have been reported with such therapy (Cesur 2003). Vitamin D may also be administered in smaller doses over several weeks. Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation/sunlight and improved nutrition are also recommended. Rich dietary sources of vitamin D include liver, fish, milk, infant formula and other foods fortified with vitamin D such as margarine.

Calcium alone has also been used in the treatment of nutritional rickets especially in children who reside in sunny countries and who are believed to have adequate vitamin D production from exposure to UV light but are deficient in calcium due to low dietary intake. In supplements, the two main forms of calcium are calcium carbonate and calcium citrate. Calcium carbonate is inexpensive, convenient and readily available. It is highly dependent on stomach acid for absorption, and works more efficiently when taken with food. Calcium citrate is well absorbed and can be taken with or without food. Other forms of calcium in supplements or fortified foods are calcium phosphate, calcium lactate and calcium gluconate. These supplements contain varying amounts of elemental calcium. Calcium citrate contains 21% calcium, and calcium carbonate 40% calcium by weight. When these supplements are taken, the percentage of calcium absorbed by the body depends on the total amount of elemental calcium taken at one time. As the amount of elemental calcium taken increases, the percentage absorbed decreases. Absorption is highest with doses of elemental calcium 500 mg or less (Ross 2011).

Adverse effects of vitamin D or calcium

Adverse effects from vitamin D or calcium are uncommon if given in the correct dose. However, if doses of vitamin D or calcium are too high, hypercalcaemia (high levels of calcium in the blood), which can cause soft tissue calcification and kidney stones, and hypercalciuria (high levels of calcium in the urine) with varying degrees of renal insufficiency, can occur. High calcium intake can cause constipation, and may also interfere with the absorption of iron and zinc.

Vitamin D toxicity, also called hypervitaminosis D, is a rare but potentially serious condition that occurs when there are excessive amounts of vitamin D in the body due to very high doses of vitamin D supplements. Hypercalcaemia is responsible for most of the symptoms of vitamin D toxicity. Early symptoms of vitamin D toxicity include gastrointestinal disorders such as anorexia, diarrhoea, constipation, nausea and vomiting. Other symptoms include bone pain, drowsiness, irregular heartbeat, loss of appetite, muscle and joint pain, frequent urination, excessive thirst, weakness, nervousness, itching and kidney stones (Schwalfenberg 2007).

How the intervention might work

Vitamin D deficiency results in the failure of mineralisation of growing bones manifesting clinical and radiological features of rickets. Vitamin D replacement therapy in the presence of adequate dietary calcium results in the resolution of the features of rickets. Calcium deficiency (from inadequate dietary intake or malabsorption) increases the catabolism of vitamin D and ultimately results in vitamin D deficiency and rickets. In such settings where poor dietary calcium intake is the dominant cause of rickets, calcium replacement therapy (with or without vitamin D) will be needed to achieve resolution of the symptoms of rickets (Pettifor 2004).

Interventions for the treatment of nutritional rickets include supplementation of vitamin D, calcium supplementation or a combination of both. Educational interventions include nutritional counselling and advice on exposure to sunlight.

Why it is important to do this review

Rickets constitutes a significant public health problem, particularly in low‐ and middle‐income countries. In recent years there has been a re‐emergence of rickets in high‐income countries such as the UK and the USA where it was thought to have been eradicated (Allgrove 2004; Nield 2006; Pal 2001). Most occurrences of rickets are in children with dark skin or of non‐white origin such as African Americans and South East Asians.

Although vitamin D deficiency has been thought to be the predominant cause of nutritional rickets there is evidence that calcium deficiency is the major cause of rickets in Africa and some parts of Asia. It has been observed that where calcium deficiency is primarily responsible for the occurrence of rickets and where levels of 25‐OHD are normal, treatment with vitamin D alone may not result in resolving the disease (Thacher 1999). A combination of vitamin D and calcium or calcium alone has been recommended in these instances. There is evidence that low dietary calcium intakes play a significant role in the pathogenesis of rickets which has implications for the choice of appropriate treatment and preventive interventions (Pettifor 2014b).

A number of studies have been carried out to compare vitamin D and calcium in the treatment of nutritional rickets (both calcium deficiency and vitamin D deficiency rickets). Studies have also compared various regimens of vitamin D for the treatment of rickets. Thacher 2006 conducted a narrative review of non‐randomised studies that assessed the prevalence and causes of nutritional rickets. The objective and findings presented by Thacher 2006 did not include evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions for treating nutritional rickets. A search of major electronic health research databases found no systematic review or meta‐analysis of studies that assessed the effects of these interventions. Therefore, there is a need to carry out a systematic review to assess the effects of interventions for treating nutritional rickets.

Objectives

To assess the effects of vitamin D, calcium or a combination of vitamin D and calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

Children up to 18 years of age with nutritional rickets.

Diagnostic criteria for (nutritional) rickets

Nutritional rickets refers to rickets confirmed by a combination of clinical, radiological and biochemical features, and shown to be due to any of the following aetiological categories (Pettifor 2004): vitamin D deficiency, calcium deficiency or a combination of vitamin D and calcium deficiency.

Clinical diagnosis is established by carrying out a complete physical and dental examination of the child and taking the medical, social and nutritional history to identify following features: enlargement of wrists, craniotabes (softening of the skull bones), rachitic rosary, bowing of legs, pigeon chest and frontal bossing. Other important clinical findings, apart from bone deformities, that will be used to establish clinical diagnosis, are hypocalcaemic convulsions, hypotonia (muscle weakness) and growth retardation. The diagnosis of rickets is supported by radiological and biochemical features characteristic of the disease.

Radiological investigations for diagnosis of rickets include radiographs of the wrists or knees. Key radiological findings are metaphyseal cupping or fraying and widening of epiphysis. Other radiological findings may include fractures, osteopenia or widened wrists and ankles.

Biochemical investigations include assessment of calcium, phosphorus and ALP blood levels. Rickets is characterised by low blood calcium levels (less than 8.5 mg/dL), low phosphorus levels (less than 4.5 mg/dL) and high ALP levels (greater than 461 U/L). There may be other abnormal biochemical findings such as elevated parathyroid hormone levels (greater than 55 pg/mL) and low vitamin D as evidenced by low 25‐OHD levels (less than 15 ng/dL).

Types of interventions

We investigated the following comparisons of intervention versus control/comparator.

Interventions and comparators

Calcium compared with vitamin D.

Vitamin D plus calcium compared with calcium or vitamin D.

Concomitant interventions had to be identical in both the intervention and comparator groups to establish fair comparisons. If a study included multiple groups, we included any group that met the inclusion criteria for this review. We investigated any type, dose and route of administration of vitamin D or calcium, as well as different forms of vitamin D or calcium. Furthermore, we distinguished between supplementation and fortification interventions.

Minimum duration of intervention

For calcium given alone or in combination with vitamin D, the minimum duration was at least eight weeks. This did not apply to studies that used one day high‐dose therapy.

Minimum duration of follow‐up

We included studies with a minimum duration of interventions of eight weeks.

We defined any follow‐up period going beyond the original time frame for the primary outcome measure as specified in the power calculation of the studies' protocols as an extended follow‐up period (also called open‐label extension study) (Buch 2011; Megan 2012).

Summary of specific exclusion criteria

Preterm children.

Children above 18 years of age.

Children with comorbidities such as HIV, sickle cell anaemia.

Quasi‐randomised trials and other non‐RCT study designs.

Types of outcome measures

We did not exclude studies because one or several of our primary or secondary outcome measures were not reported in the publication. When a study reported none of our primary or secondary outcomes, we did not include this study but planned to provide some basic information in an additional table.

We extracted the following outcomes, using the methods and time points specified below.

Primary outcomes

Healing of rickets.

Morbidity.

Adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

All‐cause mortality.

Health‐related quality of life.

Growth pattern.

Socioeconomic effects.

Method of outcome measurement

Healing of rickets: defined as resolution of clinical and radiological features of rickets.

Morbidity: defined as infections (such as acute lower respiratory tract infections, e.g. pneumonia), hypocalcaemic seizures, fractures.

Adverse events: such as hypercalcaemia, hypercalciuria, hypervitaminosis D.

All‐cause mortality: defined as death from any cause.

Health‐related quality of life: evaluated by a validated instrument such as Short Form 36 questionnaire (SF‐36).

Growth pattern: defined as differences in height, weight, height for age, weight for age and weight for height scores.

Socioeconomic effects: defined as cost of treatment, resources lost due to illness or due to absence of the caregiver from work, cost of visits to hospital or health facility.

Timing of outcome measurement

Healing of rickets and socioeconomic effects: measured at 12 or more weeks after commencement of therapy.

Morbidity: at any time from when the intervention was administered.

Adverse events: from commencement of the intervention to at least four weeks after stopping treatment.

All‐cause mortality: measured at any time during the study.

Health‐related quality of life: measured at any time during follow‐up.

Growth pattern: at one or more years after commencement of therapy.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following sources on 25 July 2019 from inception of each database to the specified date and placed no restrictions on the language of publication.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO), 25 July 2019.

MEDLINE Ovid (Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily and Ovid MEDLINE; from 1946 to 23 July 2019).

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database; from 1982 to "Last update: 15/07/2019").

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), 25 July 2019.

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/trialsearch/), 25 July 2019.

We did not include Embase in our search, as RCTs indexed in Embase are now prospectively added to CENTRAL via a highly sensitive screening process (Cochrane 2018).

We continuously applied a MEDLINE (via OvidSP) email alert service established by the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders (CMED) Group to identify newly published trials using the same search strategy as described for MEDLINE (Appendix 1).

Searching other resources

We tried to identify other potentially eligible studies or ancillary publications by searching the reference lists of included studies, systematic reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports. In addition, we contacted authors of included studies to identify additional information on the retrieved studies and establish if further studies that we may have missed exist. We define grey literature as records detected in ClinicalTrials.gov or WHO ICTRP.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two review authors (MC, DG, JO) independently scanned the abstract, title or both, of every record we retrieved in the literature searches, to determine which studies we should assess further. We obtained the full text of all potentially relevant records. We resolved any disagreements through consensus or by recourse to a third review author (MM). If we could not resolve a disagreement, we categorised the study as a 'study awaiting classification' and contacted the study authors for clarification. We presented an adapted PRISMA flow diagram to shown the process of study selection (Liberati 2009).

We did not use abstracts or conference proceedings for data extraction because this information source does not fulfil CONSORT requirements which is "an evidence‐based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomised trials" (CONSORT; Scherer 2018).

Data extraction and management

For studies that fulfilled our inclusion criteria, two review authors (MC, JO) independently extracted key information on participants, interventions and comparators. We reported data on efficacy outcomes and adverse events using standardised data extraction sheets from the Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders (CMED) Group. We resolved any disagreements by discussion, or if required, by consultation with a third review author (MM or DG) (for details, see Characteristics of included studies table; Table 4; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7; Appendix 8; Appendix 9; Appendix 10; Appendix 11; Appendix 12; Appendix 13; Appendix 14; Appendix 15; Appendix 16).

1. Overview of study populations.

| Study ID (design) | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Description of power and sample size calculation | Screened/eligible (n) | Randomised (n) | Analysed (n) | Finishing study (n) | Randomised finishing study (%) | Follow‐up |

| Thacher 2014 (parallel RCT) | I: calcium + vitamin D | "Based on the primary outcome measures of radiographic score and serum alkaline phosphatase values and SDs based on previous studies (1.6 for radiographic score and 150 U/L in alkaline phosphatase), 40 subjects in each treatment group would provide 80% power and 95% CI to detect a difference between groups of 1.0 in final radiographic score and 100 U/L in alkaline phosphatase." | 254 | 44 | 43 | 43 | 97.7 | 24 weeks |

| C: calcium + placebo | 28 | 25 | 25 | 89.3 | ||||

| total: | 72 | 68 | 68 | 94.4 | ||||

| Aggarwal 2013 (parallel RCT) | I1: calcium + vitamin D | — | 100 | 22 | 20 | 20 | 90.9 | 12 weeks |

| I2: calcium | 22 | 17 | 17 | 77.3 | ||||

| C: vitamin D | 23 | 19 | 19 | 82.6 | ||||

| total: | 67 | 56 | 56 | 83.6 | ||||

| Balasubramanian 2003 (parallel RCT) | I: calcium + vitamin D | — | — | 14 | 4 | 4 | 28.6 | 3 months |

| C: calcium | 10 | 4 | 4 | 40 | ||||

| total: | 24 | 8 | 8 | 33 | ||||

| Thacher 1999 (parallel RCT) | I1: calcium + vitamin D | — | 297 | 40 | 38 | 38 | 95 | 24 weeks |

| I2: calcium + placebo | 42 | 34 | 35 | 83.3 | ||||

| C: vitamin D + placebo | 41 | 37 | 37 | 90.2 | ||||

| total: | 123 | 109 | 110 | 89.4 | ||||

| Grand total | All interventions | 184 | 157 | |||||

| All comparators | 102 | 85 | ||||||

| All interventions and comparators | 286 | 242 | ||||||

— denotes not reported

C: comparator; CI: confidence interval; I: intervention; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; n: number of participants; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SD: standard deviation.

We planned to provided information, including the study identifier for potentially relevant ongoing studies in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table and in Appendix 7 entitled 'Matrix of study endpoint (publications and trial documents)'. We tried to find the protocol for each included study and reported primary, secondary and other outcomes from these protocols alongside the data from the study publications in Appendix 7.

We emailed all authors of included studies to enquire whether they would be willing to answer questions regarding their studies. We presented the results of this survey in Appendix 13. Thereafter, we sought relevant missing information on the study from the primary study author(s), if required.

Dealing with duplicate and companion publications

In the event of duplicate publications, companion documents or multiple reports of a primary study, we maximised the information yield by collating all available data and used the most complete dataset aggregated across all known publications. We listed duplicate publications, companion documents, multiple reports of a primary study and study documents of included studies (such as trial registry information) as secondary references under the study ID of the included study. Furthermore, we also listed duplicate publications, companion documents, multiple reports of a study and trial documents of excluded studies (such as trial registry information) as secondary references under the study ID of the excluded study.

Data from clinical trials registers

If data from included studies were available as study results in clinical trials registers, such as ClinicalTrials.gov or similar sources, we made full use of this information and extracted data. If there was also a full publication of the study, we collated and critically appraised all available data. If an included study was marked as a completed study in a clinical trial register, but no additional information was available, we added this study to the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MC, DG) independently assessed the risk of bias of each included study. We resolved any disagreements by consensus or by consultation with a third review author (MM). In the case of disagreement, we consulted the rest of the review author team and made a judgement based on consensus. If adequate information was not available from study authors, study protocols or both, we contacted the study authors to request missing data on risk of bias items.

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2019a), assigning assessments of low, high or unclear risk of bias (for details, see Appendix 2; Appendix 3). We evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions according to the criteria and associated categorisations contained therein (Higgins 2019a).

We presented a 'Risk of bias' graph and a 'Risk of bias' summary figure (Figure 1; Figure 2). We distinguished between self‐reported, investigator‐assessed and adjudicated outcome measures.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included trials (blank cells indicate that the particular outcome was not measured in some trials).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included trial ((blank cells indicate that the particular outcome was not measured in some trials)

We considered the following self‐reported outcomes.

Morbidity.

Adverse events.

Health‐related quality of life.

Socioeconomic effects.

We considered the following outcomes to be investigator‐assessed.

Healing of rickets.

Morbidity.

Adverse events.

All‐cause mortality.

Growth pattern.

Socioeconomic effects.

Summary assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias for a study across outcomes

Some risk of bias domains, such as selection bias (sequence generation and allocation sequence concealment), affect the risk of bias across all outcome measures in a study. In case of high risk of selection bias, all endpoints investigated in the associated study were marked as high risk. Otherwise, we did not perform a summary assessment of the risk of bias across all outcomes for a study.

Risk of bias for an outcome within a study and across domains

We assessed the risk of bias for an outcome measure by including all entries relevant to that outcome (i.e. both study level entries and outcome specific entries). We considered low risk of bias to denote a low risk of bias for all key domains, unclear risk to denote an unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains and high risk to denote a high risk of bias for one or more key domains.

Risk of bias for an outcome across studies and across domains

To facilitate our assessment of the certainty of evidence for key outcomes, we assessed risk of bias across studies and domains for the outcomes included in the 'Summary of finding' tables. We defined the evidence as being at low risk of bias when most information came from studies at low risk of bias, unclear risk of bias when most information came from studies at low or unclear risk of bias, and high risk of bias when a sufficient proportion of information came from studies at high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

When at least two included studies are available for a comparison and a given outcome, we tried to express dichotomous data as a risk ratio (RR) or odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes measured on the same scale (e.g. weight loss in kilograms), we estimated the intervention effect using the mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs. For continuous outcomes measuring the same underlying concept (e.g. health‐related quality of life) but using different measurement scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD). We expressed time‐to‐event data as hazard ratio (HR) with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We took into account the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over studies, cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome. If more than one comparison from the same study was eligible for inclusion in the same meta‐analysis, we either combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison or appropriately reduced the sample size so that the same participants did not contribute more than once (splitting the 'shared' group into two or more groups). While the latter approach offers some solution to adjusting the precision of the comparison, it does not account for correlation arising from the same set of participants being in multiple comparisons (Higgins 2019b).

We attempted to re‐analyse cluster‐RCTs that had not appropriately adjusted for potential clustering of participants within clusters in their analyses. The variance of the intervention effects was inflated by a design effect (DEFF). Calculation of a DEFF involves estimation of an intracluster correlation (ICC). We obtained estimates of ICCs through contact with authors, or imputed them using estimates from other included studies that reported ICCs, or using external estimates from empirical research (e.g. Bell 2013). We planned to examine the impact of clustering using sensitivity analyses.

Dealing with missing data

If possible, we obtained missing data from the authors of the included studies. We carefully evaluated important numerical data such as screened, randomly assigned participants as well as intention‐to‐treat, and as‐treated and per‐protocol populations. We investigated attrition rates (e.g. dropouts, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals), and we critically appraised issues concerning missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward).

In studies where the standard deviation (SD) of the outcome was not available at follow‐up or could not be calculated, we standardised by the mean of the pooled baseline SD from those studies that reported this information.

Where included studies did not report means and SDs for outcomes and we not received the needed information from study authors, we imputed these values by estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of the sample (Hozo 2005).

We investigated the impact of imputation on meta‐analyses by performing sensitivity analyses, and we reported per outcome which studies were included with imputed SDs.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In the event of substantial clinical or methodological heterogeneity, we did not report study results as the pooled effect estimate in a meta‐analysis.

We identified heterogeneity (inconsistency) by visually inspecting the forest plots and by using a standard Chi² test with a significance level of α = 0.1 (Deeks 2019). In view of the low power of this test, we also considered the I² statistic – which quantifies inconsistency across studies – to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta‐analysis (Higgins 2002; Higgins 2003). When we identified heterogeneity, we attempted to determine the possible reasons for it by examining individual characteristics of the study and subgroups.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we included 10 or more studies that investigated a particular outcome, we used funnel plots to assess small study effects. Several explanations may account for funnel plot asymmetry, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to study size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small studies) and selective non‐reporting (Kirkham 2010). Therefore, we interpreted results carefully (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We planned to undertake (or display) a meta‐analysis only if participants, interventions, comparisons and outcomes were sufficiently similar to ensure a result that was clinically meaningful. Unless good evidence shows homogeneous effects across studies, we primarily summarised data that were of low risk of bias using a random‐effects model (Wood 2008). We interpreted random‐effects meta‐analyses with due consideration to the whole distribution of effects, ideally by presenting a prediction interval (Borenstein 2017a; Borenstein 2017b; Higgins 2009). A prediction interval needs at least three studies to be calculated and specifies a predicted range for the true treatment effect in an individual study (Riley 2011). For rare events (such as event rates below 1%), we used Peto's OR method, provided that there was no substantial imbalance between intervention and comparator group sizes and intervention effects are not exceptionally large. In addition, we also performed statistical analyses according to the statistical guidelines presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2019).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We expected the following characteristics to introduce clinical heterogeneity, and we planned to carry out subgroup analyses for these, including investigation of interactions (Altman 2003).

Studies in low‐ and middle‐income countries compared to those in high‐income countries.

Dosing scheme.

Age.

Sex.

Type of supplementation/fortification.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors (when applicable) on effect sizes by restricting analysis to the following.

Published studies.

Taking into account risk of bias, as specified in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section.

Very long or large studies, to establish the extent to which they dominated the results.

We used the following filters, if applicable: diagnostic criteria, imputation used, language of publication (English versus other languages), source of funding (industry versus other) or country (depending on data).

We also tested the robustness of results by repeating the analyses using different measures of effect size (RR, OR, etc.) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models).

Certainty of the evidence

We presented the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome specified below, according to the GRADE approach, which takes into account issues related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) and external validity (such as directness of results). Two review authors (MC, DG) independently rated the certainty of evidence for each outcome. We resolved any differences in the assessment by discussion or consulting a third review author (MM).

We included an appendix entitled 'Checklist to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments', to help with standardisation of the 'Summary of findings' tables (Meader 2014). Alternatively, we planned to use GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GDT) software and planned to present evidence profile tables as an appendix (GRADEpro GDT 2015). We presented results for the outcomes as described in the Types of outcome measures section. If meta‐analysis was not possible, we presented the results in a narrative format in the 'Summary of findings' table. We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of studies using footnotes, and we made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the Cochrane Review where necessary.

'Summary of findings' table

We presented a summary of the evidence in a 'Summary of findings' table. This provided key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect, in relative terms and as absolute differences, for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies; the numbers of participants and studies addressing each important outcome; and a rating of overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome. We created the 'Summary of findings' table based on the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2019), along with Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2014). We presented in the 'Summary of findings' table the following interventions: calcium compared with vitamin D, vitamin D plus calcium compared with vitamin D and vitamin D plus calcium compared with calcium.

We reported the following outcomes, listed according to priority.

Healing of rickets.

Morbidity.

Adverse events.

All‐cause mortality.

Health‐related quality of life.

Growth pattern.

Socioeconomic effects.

Results

Description of studies

For a detailed description of studies, see Table 4; Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

Electronic search of databases and the continuous MEDLINE (via OvidSP) search yielded 4562 records. We did not identify any additional records through searching of non‐databases sources. After removal of duplicates, we obtained and screened 3952 unique records. Three review authors independently screened titles and abstracts of these records following which 3937 records were excluded. We assessed the full text of 15 studies for eligibility and four studies (five publications) met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 3).

3.

Trial flow diagram.

Included studies

Four studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. A detailed description of the characteristics of included studies is presented elsewhere (see Characteristics of included studies table; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6). The following is a succinct overview.

Source of data

All data included in the review were obtained from reports published in medical journals except for some additional data which was obtained through correspondence with the study authors by email. Specific data obtained from study authors were:

baseline data on number of children randomised to study groups for Thacher 1999;

data on adverse events, serum alkaline phosphate values, serum 25‐OHD values and radiological scores at 12 and 24 weeks for Thacher 2014;

data on blinding of participants and personnel, study design and reasons for loss to follow‐up for Aggarwal 2013.

For details of correspondence with authors, see Appendix 13.

Comparisons

Two of the included studies had two groups which compared vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium alone or calcium with placebo (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 2014). The two other included studies had three groups which compared vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium (alone or with placebo) versus vitamin D (alone or with placebo) (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999). Doses and route of administration of vitamin D varied between studies. Four studies/study arms administered calcium orally in the form of calcium lactate or calcium carbonate and the form was unclear in one study (Appendix 4).

Overview of study populations

Studies included 286 participants.

The number of participants randomised to intervention groups was 184 and comparator groups was 102.

The percentage of participants finishing the studies was 85.3% in the intervention groups and 83.3% in the comparator groups.

Individual sample size in the studies ranged from 24 to 123.

Study design

All included studies were parallel RCTs. Two studies had a two‐group parallel design (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 2014), and two studies had a three‐group parallel design (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999).

Three studies had a superiority design (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014); Aggarwal 2013 had an equivalence design.

Two studies gave placebo in conjunction with an active treatment (Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014).

Two studies were performed at a single centre except for Balasubramanian 2003 that was performed at two centres and Thacher 1999 for which the number of centres was unclear.

One study was not blinded (Aggarwal 2013), and it was unclear whether participants and personnel were blinded in the remaining three studies.

Three studies blinded outcome assessors (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014). It was unclear whether the assessors were blinded in the remaining study (Balasubramanian 2003).

Balasubramanian 2003 did not state the year in which the study was conducted. The remaining three studies were conducted between 1996 and 2009.

Mean duration of the intervention in the studies ranged from 12 weeks to 24 weeks while the duration of follow‐up also ranged from 12 weeks to 24 weeks.

There was no run‐in period for any of the included studies.

None of the studies was terminated before time due to benefit or harm.

Settings

Two of the studies were conducted in India (Aggarwal 2013; Balasubramanian 2003), and two in Nigeria (Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014). All were conducted in hospital facilities.

Participants

All participants were from low‐ to middle‐income countries.

Sixty‐eight per cent of participants were of African ethnicity (Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014), and 32% were Asian (Aggarwal 2013; Balasubramanian 2003).

Only one study reported the duration of rickets and this ranged from 0.5 months to 108 months (Thacher 2014).

One hundred and fifty‐five participants were girls and 131 were boys. Two studies recruited almost equal proportion of boys and girls (Aggarwal 2013; Balasubramanian 2003), while the other two studies recruited more girls (Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014).

The mean age of the participants ranged from six months to 14 years.

None of the studies reported comorbidities, cointerventions or comedications used by participants.

The major exclusion criteria in the included studies were a history of renal disease, liver diseases or tuberculosis; history of consuming calcium, vitamin D supplements or multivitamins in the preceding three months to six months; history of treatment with anticonvulsant or antiepileptic drugs and cases presenting with hypocalcaemic seizures.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of rickets was confirmed biochemically or radiologically, or both. Aggarwal 2013 and Thacher 2014 diagnosed rickets radiologically (radiographs of the wrist and knee) using Thacher's 10‐point scale (Thacher 2000). Thacher's 10‐point scale is a scoring system to assess the radiographic changes in the wrists and knees of people with rickets, where 0 represents no rickets and 10 represents severe rickets. In Aggarwal 2013, a radiological score of greater than 1.5 indicated rickets, while Thacher 2014 diagnosed children with rickets as those with a radiographic score of at least 2.5 on a 10‐point scale. In addition, Aggarwal 2013 reported that based on currently accepted paediatric standards, children with serum 25‐OHD levels less than 20 ng/mL were considered to have vitamin D deficiency.

Balasubramanian 2003 confirmed the diagnosis of rickets if the children had characteristic radiological changes and elevated serum ALP level (SAP) (greater than 375 IU/L). However, the author did not describe how radiological changes were assessed. Thacher 1999 diagnosed rickets clinically and radiologically. Children with deformities characteristic of rickets (such as genu varum and genu valgum) had radiography of the wrists and knees and active rickets was diagnosed if the epiphyseal plate was wider than normal and there was concave cupping or fraying of the metaphyseal margins on the radiographs.

Interventions

None of the included studies reported administration of any treatment before the start of the study.

Two studies had three groups comparing vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium or vitamin D (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999). The remaining two studies compared vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 2014).

Three studies administered calcium orally, as calcium carbonate (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014), while one study did not specify the form of elemental calcium used (Aggarwal 2013). Two studies administered vitamin D orally (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 2014), and two administered vitamin D intramuscularly (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999).

Total daily doses of calcium and vitamin D varied between studies (Appendix 4).

Two studies used a placebo (Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014). However, the placebo was not given alone but in conjunction with an active treatment (Appendix 4).

All studies used adequate interventions and comparators.

Outcomes

All four included studies explicitly stated a primary/secondary endpoint in their publications. Healing of rickets was the most commonly defined primary outcome (Appendix 7). All studies reported healing of rickets. Only one study reported on morbidity and growth pattern (Thacher 1999). None of the studies reported on all‐cause mortality, health‐related quality of life and socioeconomic effects. One study reported adverse events (Aggarwal 2013). Only two studies had trial registration documents (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 2014). The endpoints reported in Aggarwal 2013 did not differ from the prespecified endpoints in the trial document. Some of the secondary outcomes specified by Thacher 2014 were not reported in the publication; however, these did not include any of the outcomes of interest. The number of outcomes of interest reported by the studies ranged between one and three. Definition of endpoint for healing of rickets based on radiological and biochemical criteria was provided by all the studies, although these varied. Adverse events, morbidity or growth pattern were not defined as study endpoints. Aggarwal 2013 reported specific adverse events and Thacher 1999 reported fractures (type of morbidity) at different time points in the study.

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies after evaluation of the full publication. The main reasons for exclusion were that they were not RCTs (for further details, see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

Studies awaiting classification

One study is awaiting classification as we could not obtain a copy of the publication (El'chaninov 1969).

Ongoing studies

We found no ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details on the risk of bias of the included studies, see Characteristics of included studies table.

For an overview of review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for individual studies and across all studies, see Figure 1 and Figure 2.

Allocation

One study was at low risk of selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment) (Aggarwal 2013). In two studies, there was random sequence generation but it was unclear whether there was allocation concealment (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 2014). Although we judged allocation concealment to be adequate in Thacher 1999, the method of random sequence generation was unclear.

Blinding

None of the included studies stated explicitly that blinding of the participants and personnel was undertaken. However, we were able to confirm from the study authors that there was no blinding of participants or personnel in Aggarwal 2013. In three studies, there was insufficient information to determine whether participants and personnel were blinded (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014).

We judged blinding of participants and personnel to be adequate for three studies for healing of rickets (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014). Only one study reported on adverse events (Aggarwal 2013). As neither the participants or personnel were blinded in this study, we judged blinding of participants and personnel for adverse events at high risk of performance bias. Similarly, only Thacher 1999 assessed and reported on morbidity (fractures). We judged the risk of performance bias to be low for this outcome. Two studies reported growth pattern (Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014). We considered the risk of performance bias for this outcome to be low.

One study stated explicitly that outcome assessors were blinded (Aggarwal 2013). Two studies blinded outcome assessors for some of the outcomes (Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014). Specifically, in Thacher 1999, study personnel who assessed healing of rickets were blinded. However, it was unclear whether personnel that assessed growth pattern and morbidity were blinded. Similarly in Thacher 2014, it was not clear whether personnel assessing growth pattern or healing of rickets were blinded. However, we judged detection bias for these studies to be low because the outcomes were objective and were unlikely to be affected by absence of blinding. One study did not provide enough information to enable us assess whether outcome assessors in the study were blinded (Balasubramanian 2003).

Overall, we judged detection bias for healing of rickets to be low. Three studies had low risk of detection bias (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014), while we were unable to determine whether outcome assessors were blinded in one study (Balasubramanian 2003).

We judged the overall risk of detection bias to be low for adverse events, morbidity and growth pattern. Only one study reported on adverse events (Aggarwal 2013) and one on morbidity (Thacher 1999). Two studies reported on growth pattern (Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014).

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition rates varied widely, being 6% in Thacher 2014, 11% in Thacher 1999, 16% in Aggarwal 2013, and 67% in Balasubramanian 2003. All four included studies reported losses to follow‐up. One of the studies reported the reasons for loss to follow‐up as failure of participants to return (Thacher 2014). We were, however able to obtain reasons for loss to follow‐up for one additional study by contacting study authors (Aggarwal 2013). The reasons given by the study authors were the participants were not contactable, felt they were well or shifted treatment to another hospital.

We judged overall bias due to attrition to be unclear for most of the reported outcomes. However, Balasubramanian 2003 and Aggarwal 2013 had high loss to follow‐up and we judged this to have a possible impact on healing of rickets.

None of the studies used intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Selective reporting

Two studies had a published protocol (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 2014). We judged the risk of reporting bias to be low for Aggarwal 2013 as all outcomes were reported as prespecified in the protocol. However, we considered the risk of reporting bias to be high for two studies (Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 2014). Thacher 2014 stated the primary outcome 'combined attainment of a radiographic score of 1.5 or less and a SAP concentration of 350 U/L or less' in the publication but as 'XR [radiological] healing of rickets' in the protocol. Although there was no protocol for Balasubramanian 2003, the author did not report data on radiological measurements even though these were taken. We could not ascertain the risk of reporting bias for Thacher 1999. For full details of ORBIT (Outcome Reporting Bias In Trials), see Appendix 8.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not detect any other potential sources of bias for three studies (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999; Thacher 2014). However, we judged the risk of bias for one study to be unclear because data for baseline characteristics of participants for the two groups were not separated and so it was not possible to assess if baseline imbalances existed across groups (Balasubramanian 2003).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Vitamin D or calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children.

| Vitamin D or calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children | ||||||

|

Patients: children with nutritional rickets Settings: outpatients Intervention: calcium Comparison: vitamin D | ||||||

| Outcomes | Vitamin D | Calcium | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Healing of rickets (number) Definition: normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

189 per 1000 | 617 per 1000 (301 to 1266) | RR 3.26 (1.59 to 6.69) | 71 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | — |

|

Morbidity (number) Definition: fractures Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

108 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (3 to 251) | RR 0.27 (0.03 to 2.32) | 71 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | — |

| Adverse events (number) | Not reported | — | ||||

| All‐cause mortality | Not reported | — | ||||

| Health‐related quality of life | Not reported | — | ||||

| Growth pattern | Not reported at time point stipulated in protocol (≥ 1 years after commencement of therapy) | — | ||||

| Socioeconomic effects | Not reported | — | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

*Assumed risk was derived from the event rates in the comparator groups. aDowngraded two levels because of serious imprecision (small number of participants, one study only), see Appendix 14. bDowngraded three levels because of very serious imprecision (small number of participants, one study only, and CI consistent with benefit and harm), see Appendix 14.

Summary of findings 2. Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children.

| Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children | ||||||

|

Patients: children with nutritional rickets Settings: outpatients Intervention: vitamin D + calcium Comparison: vitamin D | ||||||

| Outcomes | Vitamin D | Vitamin D + calcium | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Healing of rickets (number) Definition: normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

189 per 1000 | 579 per 1000 (282 to 1190) | RR 3.06 (1.49 to 6.29) | 75 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | — |

|

Morbidity (number) Definition: fractures Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

108 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (3 to 225) | RR 0.24 (0.03 to 2.08) | 75 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | — |

|

Adverse events (number) Definition: asymptomatic hypercalcaemia and hypercalciuria Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

See comment | RR 4.76 (0.24 to 93.19) | 39 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | 2/20 children in the vitamin D + calcium group vs 0/19 children in the vitamin D alone group had an adverse event. | |

| All‐cause mortality | Not reported | — | ||||

| Health‐related quality of life | Not reported | — | ||||

| Growth pattern | Not reported at time point stipulated in protocol (≥ 1 years after commencement of therapy) | — | ||||

| Socioeconomic effects | Not reported | — | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

*Assumed risk was derived from the event rates in the comparator groups. aDowngraded two levels because of serious imprecision (small number of participants, one study only), see Appendix 15. bDowngraded three levels because of very serious imprecision (small number of participants, one study only, and CI consistent with benefit and harm), see Appendix 15. cDowngraded three levels because of risk of bias (performance bias and attrition bias) and very serious imprecision (small number of participants, one study only, and CI consistent with benefit and harm), see Appendix 15.

Summary of findings 3. Vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children.

| Vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium for the treatment of nutritional rickets in children | ||||||

|

Patients: children with nutritional rickets Settings: outpatients Intervention: vitamin D + calcium Comparison: calcium | ||||||

| Outcomes | Calcium | Vitamin D + calcium | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Healing of rickets (number) Definition: normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

542 per 1000 | 635 per 1000 (391 to 1031) | RR 1.17 (0.72 to 1.90) | 140 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | — |

|

Morbidity (number) Definition: fractures Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

See comment | RR 0.89 (0.06 to 13.76) | 72 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | 1/38 children had a fracture in the vitamin D + calcium group vs 1/34 children in the calcium alone group. | |

|

Adverse events (number) Asymptomatic hypercalcaemia and hypercalciuria Follow‐up: 12 weeks |

See comment | RR 4.29 (0.22 to 83.57) | 37 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | 2/20 children in the calcium + vitamin D group compared to 0/17 children in the calcium alone group had an adverse event. | |

| All‐cause mortality | Not reported | — | ||||

| Health‐related quality of life | Not reported | — | ||||

| Growth pattern | Not reported at time point stipulated in protocol (≥ 1 years after commencement of therapy) | — | ||||

| Socioeconomic effects | Not reported | — | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

*Assumed risk was derived from the event rates in the comparator groups. aDowngraded one level because of risk of bias (selective reporting) and by two levels because of serious imprecision (small number of studies and CI consistent with benefit and harm), see Appendix 16. bDowngraded three levels because of very serious imprecision (small number of participants, one study only, and CI consistent with benefit and harm), see Appendix 16. cDowngraded by three levels because of risk of bias (performance bias and potential reporting bias) and very serious imprecision (small number of participants, one study only, and CI consistent with benefit and harm), see Appendix 16.

Baseline characteristics

For details of baseline characteristics, see Appendix 5 and Appendix 6.

Vitamin D versus calcium

Two studies compared vitamin D to calcium (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999). Thacher 1999 compared vitamin D plus placebo to calcium plus placebo while Aggarwal 2013 compared vitamin D alone to calcium alone.

Primary outcomes

Healing of rickets

Normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph

Aggarwal 2013 reported healing of rickets based on normal ALP and bone radiograph at 12 weeks and Thacher 1999 reported normal ALP and bone radiograph at 24 weeks. At 12 weeks, 2/17 children were healed in the calcium group compared to 3/19 in the vitamin D group. There was no clear difference in the proportion of children healed of rickets between the two groups at 12 weeks (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.14 to 3.94; P = 0.73; 1 study, 36 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). At 24 weeks, the proportion of participants who were healed of rickets was higher in the calcium group compared to the vitamin D group (RR 3.26, 95% CI 1.59 to 6.69; P = 0.001; 1 study, 71 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vitamin D versus calcium, Outcome 1 Healing of rickets (normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph).

Serum alkaline phosphatase

Two studies assessed SAP (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999). Both studies assessed SAP at 12 weeks but only one study assessed SAP at 24 weeks (Thacher 1999). At 12 weeks, there was no clear difference in the SAP of participants in the vitamin D and calcium groups (MD –37 U/L, 95% CI –129 to 56; P = 0.44; 2 studies, 107 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2), but at 24 weeks, the MD in SAP was –148 U/L in favour of calcium (95% CI –241 to –55; P = 0.002; 1 study, 71 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vitamin D versus calcium, Outcome 2 Healing of rickets (biochemical parameters). serum alkaline phosphatase.

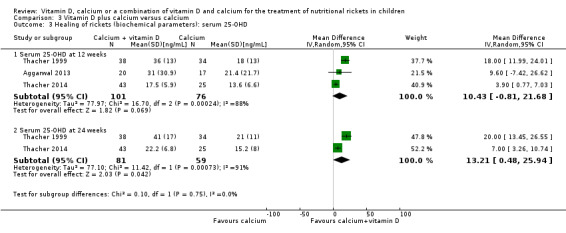

Serum 25‐hydroxy vitamin D

Two studies measured serum 25‐OHD at 12 weeks (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999) and one study at 24 weeks (Thacher 1999). At 12 weeks, comparing vitamin D with calcium showed an MD in serum 25‐OHD of –8.5 ng/mL in favour of vitamin D (95% CI –13.9 to –3.0; P = 0.002; 2 studies, 107 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3). At 24 weeks, vitamin D also improved serum 25‐OHD levels compared to calcium (MD –14.0 ng/mL, 95% CI –20.3 to –7.7; P < 0.001; 1 study, 71 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vitamin D versus calcium, Outcome 3 Healing of rickets (biochemical parameters): serum 25‐OHD.

Radiological score

At 12 and 24 weeks, there was no clear difference in the mean radiological score (Thacher's 10‐point scale) for participants in the vitamin D group when compared to the calcium group (at 12 weeks: MD 0.4, 95% CI –1.2 to 2.0; P = 0.60; 2 studies, 107 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4; at 24 weeks: MD –0.5, 95% CI –1.1 to 0.1; P = 0.10; 1 study, 71 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vitamin D versus calcium, Outcome 4 Healing of rickets (radiological).

Morbidity

Thacher 1999 reported on morbidity with regard to fractures. A comparison of vitamin D versus calcium showed no clear difference between the proportion of participants who had fractures in the two groups (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.32; P = 0.23; 1 study, 71 participants, very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5). At 24 weeks, 1/34 children had a fracture in the calcium group compared to 4/37 children in the vitamin D group.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Vitamin D versus calcium, Outcome 5 Morbidity (fractures).

Adverse events

Neither study reported adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Neither study reported all‐cause mortality.

Health‐related quality of life

Neither studies reported health‐related quality of life.

Growth pattern

Neither study reported growth pattern at the time point stipulated in our protocol (one or more years after commencement of therapy).

Socioeconomic effects

Neither study reported socioeconomic effects.

Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D

Two studies compared vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D (Aggarwal 2013; Thacher 1999).

Primary outcomes

Healing of rickets

Normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph

Two studies reported healing of rickets based on normal ALP and bone radiograph at 12 weeks (Aggarwal 2013), and at 24 weeks (Thacher 1999). At 12 weeks, there was a greater number of participants with healing of rickets in the vitamin D plus calcium group compared to vitamin D alone (RR 3.17, 95% CI 1.03 to 9.77; P = 0.05; 1 study, 39 participants; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 2.1). At 24 weeks, there was also a greater number of participants with healing of rickets in the vitamin D plus calcium group compared to vitamin D alone (RR 3.06, 95% CI 1.49 to 6.29; P = 0.002; 1 study, 75 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1). At 24 weeks, 22/38 children were healed in the vitamin D plus calcium group compared to 7/37 children in the vitamin D alone group.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D, Outcome 1 Healing of rickets (normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph).

Serum alkaline phosphatase

Aggarwal 2013 and Thacher 1999 reported SAP levels at 12 weeks, while only Thacher 1999 reported SAP at 24 weeks. At 12 weeks and 24 weeks, vitamin D plus calcium improved SAP compared with vitamin D (at 12 weeks: MD –157 U/L, 95% CI –245 to –68; P < 0.001; 2 studies, 114 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.2; at 24 weeks: MD –155 U/L, 95% CI –243 to –67; P < 0.001; 1 study, 75 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D, Outcome 2 Healing of rickets (biochemical parameters): serum alkaline phosphatase.

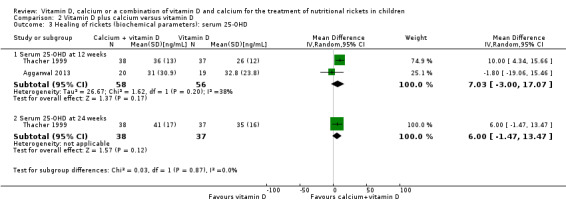

Serum 25‐hydroxy vitamin D

A comparison of serum 25‐OHD levels for vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D at showed no clear difference between the two groups at 12 weeks or 24 weeks (at 12 weeks: MD 7.0 ng/mL, 95% CI –3.0 to 17.1; P = 0.17, 2 studies, 114 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.3; at 24 weeks: MD 6.0 ng/mL, 95% CI –1.5 to 13.5; P = 0.12; 1 study, 75 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D, Outcome 3 Healing of rickets (biochemical parameters): serum 25‐OHD.

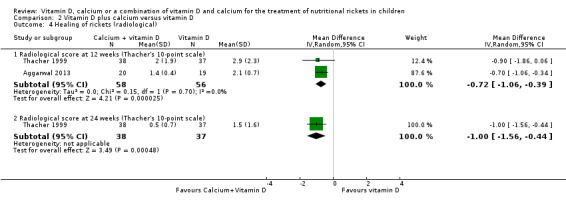

Radiological score

Aggarwal 2013 and Thacher 1999 reported radiological score (Thacher's 10‐point scale) at 12 weeks, but only Thacher 1999 reported the score at 24 weeks. At 12 and 24 weeks, the comparison favoured vitamin D plus calcium (at 12 weeks: MD –0.7, 95% CI –1.1 to –0.4; P < 0.001; 2 studies, 114 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.4; at 24 weeks: MD –1.0, 95% CI –1.6 to –0.4, P < 0.001; 1 study, 75 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D, Outcome 4 Healing of rickets (radiological).

Morbidity

Only Thacher 1999 reported the number of participants with fractures. There was no clear difference between the proportion of participants with fractures in the vitamin D plus calcium group compared to the vitamin D group (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.08; P = 0.20; 1 study, 75 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.5). At 24 weeks, 1/38 children had a fracture in the vitamin D plus calcium group compared to 4/37 children in the vitamin D alone group.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D, Outcome 5 Morbidity (fractures).

Adverse events

Aggarwal 2013 reported adverse events, namely asymptomatic hypercalcaemia and hypercalciuria. There was no clear difference in the number of adverse events in the two groups: 2/20 participants in the vitamin D plus calcium group compared to 0/19 participants in the vitamin D group had an adverse event (RR 4.76, 95% CI 0.24 to 93.19; P = 0.30; 1 study, 39 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Vitamin D plus calcium versus vitamin D, Outcome 6 Adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Neither study reported all‐cause mortality.

Health‐related quality of life

Neither study reported health‐related quality of life.

Growth pattern

Neither study reported growth pattern at the time point stipulated in our protocol (one or more years after commencement of therapy).

Socioeconomic effects

Neither study reported socioeconomic effects.

Vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium

Three studies compared vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium (Aggarwal 2013; Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 2014).

Primary outcomes

Healing of rickets

Normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph

Three studies measured the proportion of participants with normal ALP and bone radiograph at 12 weeks (Aggarwal 2013; Balasubramanian 2003; Thacher 2014). At 12 weeks, comparing the proportion of participants healed of rickets in the vitamin D plus calcium group with the calcium alone group showed a RR of 2.81 (95% CI 0.25 to 31.22; P = 0.40; 3 studies, 113 participants; very low‐quality evidence; Analysis 3.1). There was a high level of heterogeneity between the three studies. After elimination of Balasubramanian 2003, where all children in both the intervention and comparator group (4 in each group) experienced healing, the RR was 4.85 (95% CI 1.57 to 15.01) in favour of vitamin D plus calcium.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Vitamin D plus calcium versus calcium, Outcome 1 Healing of rickets (normal alkaline phosphatase and bone radiograph).