Abstract

Real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) use may lead to behavioral modifications in food selection and physical activity, but there are limited data on the utility of CGM in facilitating lifestyle changes. This article describes an 18-item survey developed to explore whether patients currently using CGM believe the technology has caused them to change their behavior.

KEY POINTS

≫ Ninety percent of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) users felt that its use contributed to a healthier lifestyle.

≫ Forty-seven percent of CGM users reported being more likely to go for a walk or do physical activity if they saw a rise in their blood glucose.

≫ Eighty-seven percent of CGM users felt that they modified their food choices based on CGM use.

≫ More research is needed into CGM as a behavior modification tool for diet and exercise in individuals with diabetes or prediabetes.

In the United States, an estimated 30.3 million people (9.4% of the population) have diabetes (1). A recent report noted that economic costs of diabetes increased by 26% from 2012 to 2017 (2). Macro- and microvascular complications from uncontrolled diabetes and multiple psychosocial factors contribute not only to the cost of diabetes, but also to quality of life deficits for those living with the disease (3).

Exercise has been shown to improve blood glucose control, reduce cardiovascular risk factors, contribute to weight loss, and improve well-being (4,5). Even low-intensity exercise improves glycemic control over 24 hours (6,7) and lowers A1C levels regardless of weight loss (8). Thus, guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and other professional societies recommend that adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes perform at least 150 minutes/week of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity (9,10). Despite these guidelines, 36.1% of U.S. adults with diabetes report having no physical activity within the previous 30 days (11), and how to motivate patients with diabetes to attempt regular exercise remains an open question. One study on motivation for exercise reported that exercise expectations are formed individually in accordance with what most people recognize as an “appropriate” level of physical activity and that there is “potential for improving exercise management by stimulating intrinsic motivation” (12).

Similarly, food choices also affect glycemic control, and limiting carbohydrate consumption and choosing high-quality (i.e., high-fiber, low–glycemic index [GI]) foods may improve glucose levels because higher-GI foods cause greater glycemic responses (13). However, data are mixed regarding the benefit of recommending low-GI foods (14–16). Current ADA dietary recommendations focus more on individualizing meal plans and conclude that, “there is not a one-size-fits-all eating pattern” for individuals with diabetes. The ADA no longer recommends specific total meal or daily carbohydrate intake levels, and there are mixed messages about low-GI diets (17). Yet, the GI does provide a good summary of postprandial glycemia (14,18–20) and, coupled with real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), it may be a useful tool for patients to better understand meal-related glycemic fluctuations.

Despite the controversy over food composition, most would generally agree that both food choices and physical activity affect glucose regulation, although responses may vary among individuals. Thus, what may be missing for individuals is direct feedback on their lifestyle choices. Real-time CGM captures nutritional intake and physical activity performance and may provide both positive and negative reinforcements of behavior, leading to sustained changes in lifestyle. However, there is limited literature on patients’ perceptions of how CGM influences their behavior. We conducted a survey of patients currently using CGM to assess their perceptions of how its use affects their lifestyle choices.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether patients with diabetes using CGM perceived that its use influences their food choices and physical activity.

Research Design and Methods

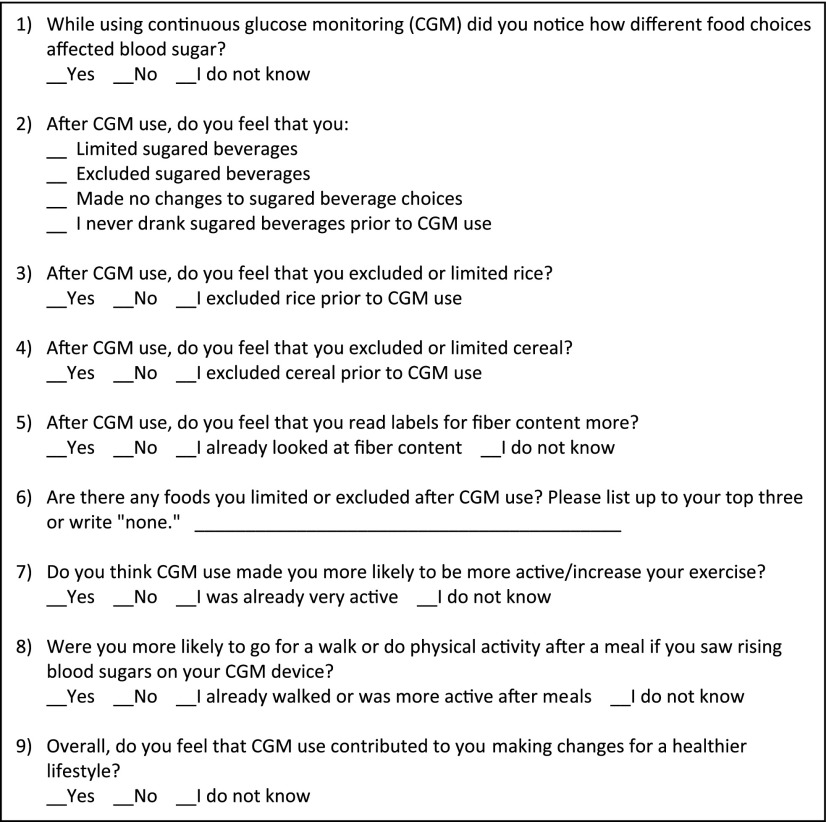

This study was reviewed and approved by the George Washington University institutional review board. We designed an 18-item questionnaire for current CGM users with any type of diabetes to determine their perceptions of how CGM affects their nutrition and physical activity choices. The survey asked questions about food choices, physical activity, and patients’ perception of change after using CGM (Figure 1). Data were collected by paper survey at an academic endocrine center over a 6-month period. Patients were recruited on an as-seen basis and given the survey anonymously. Those who declined participation were not included. Demographic data included age, sex, reported A1C, insulin pump or multiple daily injection (MDI) insulin regimen use, type of CGM device used, and duration of CGM use. Responses to the survey were collated and analyzed by descriptive statistics using Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). Results are presented below as either number or percentage of patients.

FIGURE 1.

CGM questionnaire. Demographic questions included in the survey are not shown.

Results

A total of 40 participants completed the survey. Mean age was 36 years (range 19–68) and mean BMI was 27.8 kg/m2 (SD 5.2). Seventy-eight percent of the participants (n = 31) used an insulin pump. Mean reported A1C was 7.5% (range 5.5–9.9). Fifty-five percent of the participants (n = 22) used a Dexcom CGM device, 40% (n = 16) used a Medtronic device, and 5% (n = 2) did not provide information on the type of CGM system they used. Mean duration of CGM use was >3 years (range <3 months to >3 years) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

| Participants (n = 40) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 36 (19–68) |

| Weight, lb | 180 (111–253) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.8 (21.0–47.0) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 19 (47.5) |

| Female | 21 (52.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 2 (5) |

| Caucasian | 33 (82.5) |

| Asian | 2 (5) |

| Multiple races reported | 3 (7.5) |

| Reported A1C, % | 7.5 (5.5–9.0) |

| CGM brand | |

| Medtronic | 16 (40) |

| Dexcom | 22(55) |

| FreeStyle Libre | 0 (0) |

| Missing information | 2 (5) |

| CGM use duration | |

| <3 months | 5 (12.5) |

| 3–6 months | 5 (12.5) |

| 6–12 months | 4 (10.0) |

| 1–2 years | 6 (15.0) |

| 2–3 years | 4 (10.0) |

| >3 years | 16 (40.0) |

| Insulin delivery | |

| MDI regimen | 9 (22.5) |

| Insulin pump | 31 (77.5) |

Data are mean (range) or n (%).

Eighty-seven percent of participants (n = 35) stated that their food choices changed after using CGM. Most participants either limited (15% [n = 6]) or never drank (67.5% [n = 27]) sugared beverages before CGM use. Regarding exclusion of cereals and rice from their diet, 45% of participants (n = 18) already excluded cereal before CGM use, and 55% (n = 22) made no changes in rice consumption after CGM use. On the other hand, 15% of participants (n = 6) and 22.5% of participants (n = 9) did exclude cereals and rice, respectively, after using CGM. When asked if they noticed how different food choices affected their blood glucose levels, 87.5% of participants (n = 35) reported that they did notice, 7.5% (n = 3) said they did not notice, and 5% (n = 2) were unsure. Half of the participants (n = 20) reported already reading nutrition labels for fiber content before CGM use, 15.0% (n = 6) felt that they started reading labels for fiber content after CGM use, 30% (n = 12) did not feel that CGM use led them to read labels for fiber content, and 5% (n = 2) were unsure. After CGM use, 42.5% of the participants (n = 17) felt that they were more active, 27.5% (n = 11) reported already being active before CGM use, 22.5% (n = 9) said they made no change in activity as a result of CGM use, and 7.5% (n = 3) were unsure. Increased likelihood of going for a walk or doing physical activity after a meal if CGM showed rising blood glucose levels was reported by 47.5% of participants (n = 19), 35% (n = 14) said they made no such change based on CGM, 12.5% (n = 5) already took such action before using CGM, and 5% (n = 2) were unsure. Overall 90% (n = 36) reported that CGM use contributed to a healthier lifestyle (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Key Survey Findings

| Question. | Yes. | No. | Do Not Know. | Did Before CGM Use | Missing Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noticed how food affects sugar? | 87.5 (35) | 7.5 (3) | 5.0 (2) | — | — |

| Excluded or limited sugared beverages? | 2.5 (1) | 13.0 (5) | — | 82.5 (33) | 2.5 (1) |

| Excluded or limited rice? | 22.5 (9) | 55.0 (22) | — | 22.5 (9) | — |

| Excluded or limited cereals? | 15.0 (6) | 40.0 (16) | — | 45.0 (18) | — |

| Read labels for fiber content? | 15.0 (6) | 30 (12) | 5.0 (2) | 50.0 (20) | — |

| Increased activity or exercised more? | 42.5 (17) | 22.5 (9) | 7.5 (3) | 27.5 (11) | — |

| Were more likely to go for a walk or perform physical activity after a meal in response to rising blood glucose levels on CGM system? | 47.5 (19) | 35 (14) | 5.0 (2) | 12.5 (5) | — |

| CGM contributed to a healthier lifestyle? | 90.0 (36) | 2.5 (1) | 2.5 (1) | — | 5.0 (2) |

Data are % (n).

Discussion

Education to support patient self-management and behavior modification is widely recognized as a cornerstone of diabetes care. The empowerment approach to diabetes care encompasses three guiding principles: 1) diabetes is a patient-managed disease and patients make the majority of daily decisions; 2) the patient-provider relationship is one of collaboration; and 3) when patients set their own self-management priorities, they are more likely to be motivated to initiate and sustain necessary behavior changes (21). Several studies about chronic disease management have shown that patient engagement enhances results (22).

Research has also shown that structured, frequent glucose monitoring (seven to eight times per day) improves glycemic control (23). Real-time CGM provides a full picture of glucose trends, especially overnight and after meals, that may prompt positive behavior changes (24). In two recent, large studies involving people with type 1 diabetes, CGM use improved glycemic parameters. In the DIaMonD study, participants using real-time CGM showed increased time in the target glucose range (70–180 mg/dL) of 1.3 additional hours (+76 min), a 4% decrease in overall glycemic variability, and a 40% reduction in severe hyperglycemia (>300 mg/dL) (25). The GOLD study also showed decreased standard deviation of blood glucose with CGM (68.49 vs 77.23 mg/dL, P <0.001), as well as decreased mean amplitude of glycemic excursions (26). However, data are limited regarding specifically how CGM improves glycemic variability in those not taking insulin with meals and what aspects of healthy behaviors CGM use may influence and thus improve glycemic control. Even the most recent CGM studies in type 1 and type 2 diabetes focused on A1C improvement and decreasing hypoglycemia but did not assess nutrition or exercise changes around CGM use (27–30).

Nonetheless, CGM has become more commonly used to study the impacts of physical activity, food, and medication on glycemia. One study highlighted the benefit of sustained glycemic control with low-intensity exercise using CGM (6). Another study used CGM to show that walking after meals was more beneficial to average 24-hour glucose levels than 45 minutes of continuous daily walking (7), and a more recent study in those at risk for developing diabetes found that moderate postmeal walking significantly improves 24-hour glycemic control (31). Without specific instruction on exercise, 47% of our survey participants noted that they were more likely to go for a walk after meals, an action that has been shown to improve the daily glycemic profile.

Similarly, CGM has been used to show the impact of specific foods and dietary choices. One study, for example, showed improved glycemic control with brown versus white rice and even more benefit with the consumption of glutinous brown rice (32). A more recent study demonstrated that a low-carbohydrate breakfast improved glycemic variability over 24 hours (33). Eighty-seven percent of our patients noticed glucose changes from their food choices. However, many participants had already omitted or limited certain foods before using CGM. We believe this is likely because of the duration of their disease. We hypothesis that CGM could have an even greater impact on food choices if used sooner after diagnosis.

Despite CGM becoming a more common means of assessing the effects of dietary inventions or exercise, the use of CGM to provide real-time feedback as part of interventions has been limited. As we have discussed previously (34), only one study has been performed using real-time CGM in an intervention to increase physical activity, and another study used blinded CGM coupled with counseling on the resulting CGM data to bring about improvement in physical activity (35,36). Research is even more limited on the use of CGM in interventions addressing the processes of behavior change such as goal-setting and self-efficacy with regard to physical activity (37). Research is also scarce with regard to CGM coupled with diet interventions, and there has been only one small pilot study looking at the use of real-time CGM with a low-GI diet (38).

As discussed earlier, the recent large studies of CGM in type 1 diabetes and studies in which patients with type 2 diabetes had access to real-time glucose data (either through real-time or intermittent flash CGM technology) have focused on A1C and frequency of hypoglycemia (30,39), lack any assessment of nutrition or activity, and have been performed with patients using MDI insulin regimens or insulin pumps. There has not been a study involving patients who are either not on insulin or only using basal insulin since our publication in 2011 showing initial A1C improvement and a sustained glycemic benefit with no escalation of medications at 12 months with the use of serial intermittent real-time CGM (40). However, we, too, failed to assess lifestyle modification in that study.

CGM technology continues to advance, and the improved accuracy and calibration-free options now available make it more appealing for general use. However, research into how CGM use affects lifestyle behaviors continues to be lacking, especially in patients not using insulin.

A major limitation of this study is that we did not ascertain participants’ type or duration of diabetes. We focused only on CGM use, duration of CGM use, and method of insulin delivery. CGM use among patients with type 2 diabetes at our academic center was almost nonexistent during the study period, although such use is now growing with newer flash CGM systems and improved real-time CGM technology. Thus, we suspect that most, if not all, survey participants had type 1 diabetes and a long duration of disease because the average age was 36 years, and 50% of participants had been using CGM for more than 2 years. With increasing CGM use among people with type 2 diabetes, it would be interesting to study the perspectives of individuals in this population using either real-time or “flash” intermittent scan CGM devices, as well as the perspectives of people with more recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes using CGM.

Conclusion

The three pillars of diabetes management are diet, medication, and exercise, and all significantly affect glycemic control. What remains to be shown is how CGM can serve as an adjunct to and enhance these interventions. Overall, 90% of participants in our survey felt that they had adopted a healthy lifestyle after using CGM, and a high percentage of the participants who used CGM reported food changes (i.e., limiting or excluding high-GI food such as white rice, cereals, and sugared beverages) and also increased physical activity, especially postprandially. The survey findings highlight the potential utility of CGM as a behavior modification tool in patients with diabetes and underscores the need for further research on CGM in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes or prediabetes.

Article Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Richard Amdur, PhD, and Aileen Chang, MD, for their review of the manuscript.

Duality of Interest

N.E. has received an investigator-initiated grant from Dexcom to study real-time CGM as a behavior modification tool for patients with prediabetes or diabetes. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions

N.E. wrote the manuscript. E.A.Z. researched the data, analyzed the data, and reviewed/edited the manuscript. N.E. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

E.A.Z. is currently affiliated with Faith Regional Medical Center in Norfolk, NE.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National diabetes statistics report. 2017. Available from www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2019

- 2.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2017. Diabetes Care 2018;41:917–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trikkalinou A, Papazafiropoulou AK, Melidonis A. Type 2 diabetes and quality of life. World J Diabetes 2017;8:120–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sluik D, Buijsse B, Muckelbauer R, et al. Physical activity and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1285–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tikkanen-Dolenc H, Wadén J, Forsblom C, et al.; FinnDiane Study Group . Physical activity reduces risk of premature mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes with and without kidney disease. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1727–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manders RJ, Van Dijk JW, van Loon LJ. Low-intensity exercise reduces the prevalence of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duvivier BM, Schaper NC, Hesselink MK, et al. Breaking sitting with light activities vs structured exercise: a randomised crossover study demonstrating benefits for glycaemic control and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2017;60:490–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulé NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, Wells GA, Sigal RJ. Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. JAMA 2001;286:1218–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al.; American College of Sports Medicine; American Diabetes Association . Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement executive summary. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2692–2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Yardley JE, et al. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016;39:2065–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazargan-Hejazi S, Arroyo JS, Hsia S, Brojeni NR, Pan D. A racial comparison of differences between self-reported and objectively measured physical activity among US adults with diabetes. Ethn Dis 2017;27:403–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oftedal B, Bru E, Karlsen B. Motivation for diet and exercise management among adults with type 2 diabetes. Scand J Caring Sci 2011;25:735–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster-Powell K, Holt SH, Brand-Miller JC. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:5–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brand-Miller J, Hayne S, Petocz P, Colagiuri S. Low-glycemic index diets in the management of diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2003;26:2261–2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matthan NR, Ausman LM, Meng H, Tighiouart H, Lichtenstein AH. Estimating the reliability of glycemic index values and potential sources of methodological and biological variability. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104:1004–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, et al. Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:1462–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: a consensus report. Diabetes Care 2019;42:731–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salmerón J, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, et al. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of NIDDM in men. Diabetes Care 1997;20:545–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacLeod J, Franz MJ, Handu D, et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics nutrition practice guideline for type 1 and type 2 diabetes in adults: nutrition intervention evidence reviews and recommendations. J Acad Nutr Diet 2017;117:1637–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sainsbury E, Kizirian NV, Partridge SR, Gill T, Colagiuri S, Gibson AA. Effect of dietary carbohydrate restriction on glycemic control in adults with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2018;139:239–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musacchio N, Lovagnini Scher A, Giancaterini A, et al. Impact of a chronic care model based on patient empowerment on the management of type 2 diabetes: effects of the SINERGIA programme. Diabet Med 2011;28:724–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams RJ. Improving health outcomes with better patient understanding and education. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2010;3:61–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Schikman CH, et al. Structured self-monitoring of blood glucose significantly reduces A1C levels in poorly controlled, noninsulin-treated type 2 diabetes: results from the Structured Testing Program study. Diabetes Care 2011;34:262–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Block JM. Continuous glucose monitoring: changing diabetes behavior in real time and retrospectively. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2008;2:484–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck RW, Riddlesworth T, Ruedy K, et al.; DIAMOND Study Group . Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lind M, Polonsky W, Hirsch IB, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring vs conventional therapy for glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes treated with multiple daily insulin injections: the GOLD randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:379–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolpert HA. Use of continuous glucose monitoring in the detection and prevention of hypoglycemia. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2007;1:146–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey TS, Zisser HC, Garg SK. Reduction in hemoglobin A1C with real-time continuous glucose monitoring: results from a 12-week observational study. Diabetes Technol Ther 2007;9:203–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ehrhardt NM, Chellappa M, Walker MS, Fonda SJ, Vigersky RA. The effect of real-time continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011;5:668–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck RW, Riddlesworth TD, Ruedy K, et al.; DIAMOND Study Group . Continuous glucose monitoring versus usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving multiple daily insulin injections: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:365–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiPietro L, Gribok A, Stevens MS, Hamm LF, Rumpler W. Three 15-min bouts of moderate postmeal walking significantly improves 24-h glycemic control in older people at risk for impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 2013;36:3262–3268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terashima Y, Nagai Y, Kato H, Ohta A, Tanaka Y. Eating glutinous brown rice for one day improves glycemic control in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes assessed by continuous glucose monitoring. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2017;26:421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang CR, Francois ME, Little JP. Restricting carbohydrates at breakfast is sufficient to reduce 24-hour exposure to postprandial hyperglycemia and improve glycemic variability. Am J Clin Nutr 2019;109:1302–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehrhardt N, Al Zaghal E. Behavior modification in prediabetes and diabetes: potential use of real-time continuous glucose monitoring. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2019;13:271–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoo HJ, An HG, Park SY, et al. Use of a real time continuous glucose monitoring system as a motivational device for poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;82:73–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allen NA, Fain JA, Braun B, Chipkin SR. Continuous glucose monitoring counseling improves physical activity behaviors of individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;80:371–379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen N, Whittemore R, Melkus G. A continuous glucose monitoring and problem-solving intervention to change physical activity behavior in women with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011;13:1091–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox DJ, Taylor AG, Moncrief M, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in the self-management of type 2 diabetes: a paradigm shift. Diabetes Care 2016;39:e71–e73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haak T, Hanaire H, Ajjan R, Hermanns N, Riveline JP, Rayman G. Flash glucose-sensing technology as a replacement for blood glucose monitoring for the management of insulin-treated type 2 diabetes: a multicenter, open-label randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Ther 2017;8:55–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vigersky RA, Fonda SJ, Chellappa M, Walker MS, Ehrhardt NM. Short- and long-term effects of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012;35:32–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]