Abstract

Background and study aims Optical real-time diagnosis (= resect-and-discard strategy) is an alternative to histopathology for diminutive colorectal polyps. However, clinical adoption of this approach seems sparse. We were interested in evaluating potential clinical uptake and barriers for implementation of this approach.

Methods We conducted an international survey using the “Google forms” platform. Nine endoscopy societies distributed the survey. Survey questions measured current clinical uptake and barriers for implementing the resect-and-discard strategy , perceived cancer risk associated with diminutive polyps and potential concerns with using CT-colonography as follow-up, as well as non-resection of diminutive polyps.

Results Eight hundred and eight endoscopists participated in the survey. 84.2 % (95 % CI 81.6 %–86.7 %) of endoscopists are currently not using the resect-and-discard strategy and 59.9 % (95 % CI 56.5 %–63.2 %) do not believe that the resect-and-discard strategy is feasible for implementation in its current form. European (38.5 %) and Asian (45 %) endoscopists had the highest rates of resect-and-discard practice, while Canadian (13.8 %) and American (5.1 %) endoscopists had some of the lowest implementation rates. 80.3 % (95 % CI 77.5 %–83.0 %) of endoscopists believe that using the resect-and-discard strategy for diminutive polyps will not increase cancer risk. 48.4 % (95 % CI 45.0 %–51.9 %) of endoscopists believe that leaving diminutive polyps in place is associated with increased cancer risk. This proportion was slightly higher (54.7 %; 95 % CI 53.6 %–60.4 %) when asked if current CT-colonography screening practice might increase cancer risks.

Conclusion Clinical uptake of resect-and-discard is very low. Most endoscopists believe that resect-and-discard is not feasible for clinical implementation in its current form. The most important barriers for implementation are fear of making an incorrect diagnosis, assigning incorrect surveillance intervals and medico-legal consequences.

Introduction

Diminutive polyps (≤ 5 mm) are the most common types found during colonoscopies 1 . Their histopathologic examination is costly while their potential for malignancy is low 1 2 3 . Because diminutive polyps have such a low risk for harboring or progressing to cancer it might be reasonable to forgo histopathology in favor of less costly strategies. Image enhanced endoscopy can be used for real-time optical diagnosis of colorectal polyps. Validated classification systems based on color, vascular pattern and other criteria have been developed to determine if a polyp is neoplastic or not. The approach of replacing histopathology with optical diagnosis has been named the resect-and-discard strategy 4 5 6 7 . Studies have shown that in the hands of adequately trained endoscopists, real-time optical diagnosis provides a good alternative to pathology while being more cost-effective 8 9 . Consequently, multiple gastroenterology societies have recommended adopting resect-and-discard as part of screening programs if certain quality standards can be met 10 11 12 . Clinical implementation of this approach, however, seems sparse.

We were therefore interested in evaluating the current clinical uptake and barriers for implementation of the resect-and-discard strategy, understanding the perceived cancer risk for diminutive polyps among endoscopists and potential concerns with leaving diminutive polyps unresected or with using computed tomography-colonography in screening and surveillance.

Methods

The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) criteria was used to present the results of our survey 13 .

Study design

A cross-sectional international survey study was conducted. Target population were endoscopists with active colonoscopy practice regardless of profession, case-load, or experience. The survey was developed through discussion and consensus between 3 gastroenterologists (H.P., A.B., D.vR.). The study protocol and survey were approved by the CRCHUM Institutional Review Board (CER-number: 17.063). No personal information was collected or stored during the survey.

Recruitment process

Twenty-nine Gastroenterology, Endoscopy and Surgical associations were contacted between July 2017 and May 2018 ( Table S1 ). These associations were asked to send our online survey to their members using their mailing list, newsletter or social media (Twitter and Facebook). Survey participation was on a voluntary basis. The survey was advertised as taking a total of 3 minutes to complete. No monetary or non-monetary incentives were provided for the completion of our survey. Double clicking was allowed, results were only transmitted to the database if the participant clicked on survey completed at the end of the questionnaire. The survey advertisement text is available in Appendix 1 .

Survey content

We used “Google Forms” to administer an online questionnaire comprising 26 questions distributed on five pages ( Appendix 2 ). The questions were listed in the same order for all participants. Participants were able to return to previous pages to modify their answers. The survey was only accessible through the link provided to the contacted associations.

The primary outcome was endoscopist uptake of the resect-and-discard strategy in current clinical practice. Secondary outcomes included perceived feasibility and barriers to implementation for a resect-and-discard strategy; perceived cancer risk for resect-and-discard implementation; perceived cancer risk for diminutive polyps; concerns with leaving diminutive polyps unresected; and the perceived cancer risk of adopting computed tomography (CT) colonography as primary screening and surveillance strategy.

The survey collected information on participant demographics and practice setting data including the country of practice; private, academic or mixed practice setting; training specialty; years in practice; number of yearly colonoscopies performed and practice reimbursement. The survey further assessed participants’ knowledge of the existence of the resect-and-discard strategy; current practice implementation and barriers for implementation of a resect-and-discard approach; opinion on cancer risk associated with diminutive polyps and the resect-and-discard strategy; as well as usage of forceps/snares for different polyp types. The survey questions with possible answer options can be found in Appendix 2 .

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive analysis with frequency and percentages to describe the participant’s characteristic and their answers. To examine the association between participant characteristics and survey responses, we used univariate using chi square test and multivariate analysis using multilevel logistic regression model. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered significant. For statistical analysis, SPSS 25 (Chicago, Illinois, United States) was used.

Results

The survey was distributed by nine associations ( Table S2 ). We estimated that a total of 13,818 individuals were reached through emails based on the feedback we received regarding societies’ mailing lists. An additional 8,991 individuals were reached through social media. This number was estimated by the number of unique views from our posts on social media pages or the number of people following the page at the time of the post if the number of unique views was not accessible. This resulted in a distribution to 21,807 individuals, not considering individuals that could be members of more than one association. Overall, 808 responders participated in the survey. The response rate was 3.7 %. Most of the responses received were from the ACG mailing list (459/808 responders). Response rate from ACG members was 3.8 %, which was similar to the overall response rate of 3.7 % using newsletter, mailing list and social medias ( P = 0.96).

Endoscopist demographics

The majority of survey participants were from to the United States (56.2 %), Europe (11.4 %) and Canada (9.9 %). Most participants were Gastroenterologists (84.4 %). Endoscopist practice setting was private (38.1 %), academic (28.8 %), and community-based (16.5 %). 45.5 % of endoscopists were reimbursed on a fee-for-service and 32.9 % on a salary basis. More details provided in Table 1 .

Table 1. Characteristic of survey participants.

| Characteristics | Responses (n = 808) |

| Country of practice | N (%) |

|

454 (56.2) |

|

92 (11.4) |

|

80 (9.9) |

|

61 (7.5) |

|

55 (6.8) |

|

29 (3.6) |

|

25 (3.1) |

|

12 (1.5) |

| Practice setting | |

|

308 (38.1) |

|

233 (28.8) |

|

133 (16.5) |

|

126 (15.6) |

|

8 (1.0) |

| Training and level | |

|

682 (84.4) |

|

50 (6.2) |

|

38 (4.7) |

|

14 (1.7) |

|

10 (1.2) |

|

6 (0.7) |

|

8 (1.0) |

| Years in practice | |

|

373 (46.2) |

|

166 (20.5) |

|

258 (31.9) |

|

11 (1.4) |

| Colonoscopies performed each year | |

|

33 (4.1) |

|

151 (18.7) |

|

163 (20.2) |

|

454 (56.2) |

|

7 (0.9) |

| Practice reimbursement | |

|

368 (45.5) |

|

266 (32.9) |

|

165 (20.4) |

|

9 (1.1) |

Attitudes and practices with regards to a resect-and-discard strategy

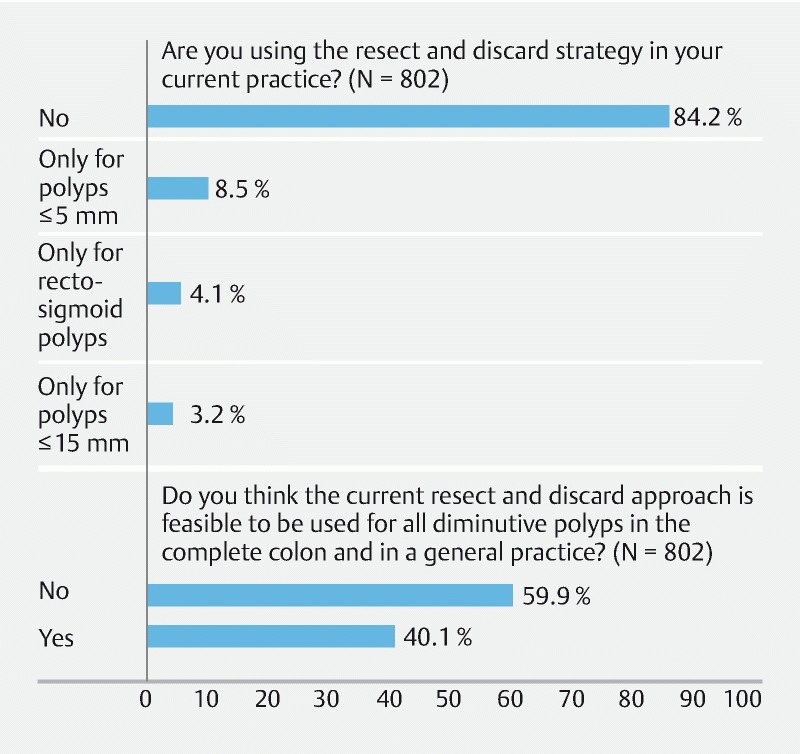

84.2 % (95 % CI 81.6 %–86.7 %) of endoscopists were not using the resect-and-discard strategy at the time of the survey, while 59.9 % (95 % CI 56.5 %–63.2 %) did not believe such an approach was feasible for implementation ( Fig. 1 ). However, 80.3 % (95 % CI 77.5–83.0 %) of endoscopists believed that using a resect-and-discard strategy for diminutive polyps would not lead to an increased cancer risk for patients. Practicing in Canada (OR = 0.25; 95 %CI 0.12–0.51) and in the United States (OR = 0.09; 95 %CI 0.05–0.14) were factors that were statistically significantly associated with not practicing a resect-and-discard strategy in the multivariate analysis ( Table 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Endoscopist usage of resect-and-discard strategy and perceptions of feasibility.

Table 2. Comparison of demographic characteristics between survey participants who use resect-and-discard in their current practice and those who don’t.

| Use of the resect-and-discard | Yes 1 n, (%) | No n, (%) | univariate analysis | multivariate analysis (OR) |

| Country of practice | 0.01 | |||

|

5 (17.2 %) | 24 (82.7 %) | n.s. | |

|

11 (13.7 %) | 69 (86.3 %) | 0.25 (0.12; 0.51) | |

|

23 (5.1 %) | 431 (94.9 %) | 0.09 (0.05; 0.14) | |

|

27 (45.0 %) | 33 (55.0 %) | n.s. | |

|

35 (38.5 %) | 56 (61.5 %) | n.s. | |

|

13 (23.6 %) | 42 (76.4 %) | n.s. | |

|

9 (44.0 %) | 14 (56.0 %) | n.s. | |

| Practice setting | 0.40 | |||

|

39 (16.7 %) | 194 (83.3 %) | n.s. | |

|

23 (17.4 %) | 109 (82.6 %) | n.s. | |

|

41 (13.3 %) | 267 (86.7 %) | n.s. | |

|

24 (18.4 %) | 102 (81.6 %) | n.s. | |

| Training and level | 0.30 | |||

|

104 (15.3 %) | 577 (84.7 %) | n.s. | |

|

4 (28.6 %) | 10 (71.4 %) | n.s. | |

|

8 (21.6 %) | 29 (78.4 %) | n.s. | |

|

3 (30.0 %) | 7 (70.0 %) | n.s. | |

|

1 (16.7 %) | 5 (83.3 %) | n.s. | |

|

7 (14.0 %) | 43 (86.0 %) | n.s. | |

| Years in practice | 0.01 | |||

|

72 (19.4 %) | 300 (80.6 %) | n.s. | |

|

23 (13.9 %) | 142 (86.1 %) | n.s. | |

|

30 (11.6 %) | 228 (88.4 %) | n.s. | |

| Colonoscopies per year | < 0.01 | |||

|

12 (36.4 %) | 21 (63.6 %) | n.s. | |

|

32 (21.2 %) | 119 (78.8 %) | n.s. | |

|

26 (16.0 %) | 136 (84.0 %) | n.s. | |

|

57 (12.6 %) | 396 (87.4 %) | n.s. | |

| Procedure reimbursement | 0.01 | |||

|

45 (12.2 %) | 323 (87.8 %) | n.s. | |

|

47 (17.7 %) | 219 (82.3 %) | n.s. | |

|

34 (20.9 %) | 129 (79.1 %) | n.s. |

n.s., not statistically significant

Includes people who answered yes for polyps up to 5 mm, yes for polyps up to 10 mm and yes for rectosigmoid polyps only

When stratified by region, the majority of endoscopists (range: 75.4–90.1 %) replied that they had heard of the resect-and-discard strategy, however, most were not using it in their current practice (range: 55–94.9 %). European (38.5 %) and Asian (45 %) endoscopists had the highest rates of resect-and-discard implementation, while Canadian (13.8 %) and American (5.1 %) endoscopists displayed lower rates. When asked if this strategy would be feasible in general practice most endoscopists replied “no” with the exception of European endoscopists, 54.3 % of whom replied “yes”. There was geographic agreement that resect-and-discard did not increase patient cancer risk ( Table S3 ).

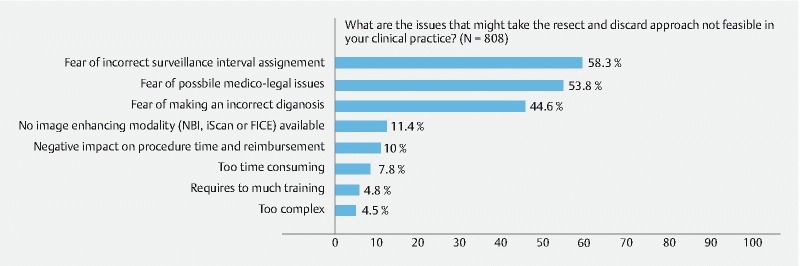

When asked about barriers for implementation of a resect-and-discard strategy 44.6 % of participants (95 % CI 41.1–48.0 %) were afraid of making a wrong diagnosis, 53.8 % (95 % CI 50.4–57.3 %) were concerned of potential medico-legal issues and 58.3 % (95 % CI 54.9–61.7 %) were afraid of assigning incorrect surveillance intervals to patients ( Fig. 2 ). For American endoscopists, the most important issue preventing implementation of a resect-and-discard strategy was fear of medico-legal issues (67.2 %), which was significantly more than the rest of the world (37.7 %; P < 0.001). Fear of making a wrong diagnosis was the main barrier for the majority of endoscopists from Australia/New Zealand (60 %) and Asia (37.7 %). For the rest of the world, fear of incorrect surveillance interval assignment was the most important issue ( Table S4 ).

Fig. 2.

Endoscopist perception of reasons for resect-and-discard non-feasibility. Multiple answers were allowed.

Perception of cancer risk associated with diminutive polyps

Overall, 63.0 % of survey participants partly or completely agreed that diminutive polyps can be left unresected until the next screening colonoscopy because of a low associated cancer risk. Endoscopists were however evenly split on the effects of leaving such polyps unresected with regards to patient cancer risk, with 48.4 % (95 % CI 45.0 %–51.9 %) thinking that leaving diminutive polyps in place would increase the cancer risk of patients ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Endoscopist perceptions on the cancer risk of diminutive polyps.

| Questions 1 | Responses; N (%) | |

| Do you think that leaving diminutive polyps increases the risk of cancer of patients? | N = 797 | |

| No | 411 | (51.6) |

| Yes | 386 | (48.4) |

| Cancer risk in a diminutive polyp is so low that such polyp can be left unresected until the next follow-up colonoscopy | N = 803 | |

| I agree | 101 | (12.6) |

| I partly agree | 405 | (50.4) |

| I partly disagree | 129 | (16.1) |

| I completely disagree | 168 | (20.9) |

| If you leave a diminutive polyp unresected, the next colonoscopy should be within a maximum of | N = 790 | |

| 1 year | 92 | (11.6) |

| 3 years | 245 | (31.0) |

| 5 years | 383 | (48.5) |

| 10 years | 70 | (8.9) |

| Do you leave diminutive polyps (up to 5 mm) in place in your current practice? | N = 808 | |

| Sometimes | 370 | (45.8) |

| In the majority of cases | 51 | (6.3) |

| Always | 4 | (0.5) |

| If appearance of the polyp suggests it is non-adenomatous | 420 | (52.0) |

| If patient is on anticoagulation medication | 170 | (21.0) |

| If patient has severe comorbidities | 161 | (19.9) |

| If follow-up colonoscopy already scheduled | 98 | (12.1) |

Multiple answers were allowed

When stratified by region, only 20 % of participants from Australia/New Zealand partly or completely agreed that diminutive polyps can be left unresected until the next screening colonoscopy, in contrast to participants from all other regions where between 58.2 and 68 % partly or completely agreed that this approach was safe. The majority of endoscopists from the United States (51.3 %), Asia (59.0 %) and South/central America (54.5 %) thought that leaving diminutive polyps in place could increase cancer risk. In contrast, most European (58.2 %) and Canadian (63.3 %) endoscopists thought that this was not so ( Table S5 ).

There was no consensus on appropriate follow-up after leaving diminutive polyps in place. 61.1 % of North American endoscopists chose a maximum of 5-year follow-up after unresected diminutive polyps compared to other regions where 74.4 % chose a 3-year or less maximum follow-up ( P < 0.001). Endoscopists from the United States (12.5 %) and Canada (10.1 %) had much higher rates of recommending the maximum option of 10-year follow-up after unresected diminutive polyps. When stratified by profession (Gastroenterologist, surgeon, internist, nurse endoscopist), 50.3 % of gastroenterologists chose a maximum of 5-year follow-up and 73.5 % of other specialties chose a maximum of 3-years or less follow-up when leaving diminutive polyps unresected ( P = 0.003).

Perceptions of non-resection of diminutive polyps and use of CT-Colonography

Overall, 52 % of endoscopists were leaving non-adenomatous appearing diminutive polyps in place in their current practice. Geographical distribution was very variable: between 37.7 % (Asia) and 80.0 % (Australia/ New Zealand) of endoscopists responded that they were leaving non-adenomatous appearing diminutive polyps in place in their current practice ( Table S5 ).

Of the surveyed endoscopists, 54.7 % (95 % CI 53.6–60.4 %) thought that current CT-colonography guidelines were “probably” or “definitely” putting patients at higher cancer risk ( Table 4 ). When stratified by region, the majority of American, European, Asian and South/Central American endoscopists agreed with that statement versus a minority of Canadian (32.5 %) and Australian/New Zealand (20 %) endoscopists.

Table 4. Endoscopist perceptions of CT-colonography, resect-and-discard and cancer risk.

| Questions | Responses; N (%) | |

| Do you think that current CT-colonography practice, which leaves polyps < 6 mm in place until the next surveillance exam, leads to an increased risk of colon cancer for the patient? | N = 804 | |

| No | 59 | (7.3) |

| Probably Not | 305 | (37.9) |

| Probably Yes | 324 | (40.3) |

| Yes | 116 | (14.4) |

| Do you think that using the resect-and-discard strategy for diminutive polyps increase the risk of cancer of patients? | N = 808 | |

| No | 639 | (80.3) |

| Yes | 157 | (19.7) |

CT, computed tomography

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study represents the largest international survey available to date studying endoscopist opinion on resect-and-discard and diminutive polyps. It is also the first providing data on geographic differences in endoscopist attitudes towards resect-and-discard. Endoscopist characteristics were also well distributed according to practice setting, practice reimbursement and years in practice which lends external validity to our data. Geographic distribution was skewed towards North America with endoscopists from the United States, Europe and Canada providing the majority of responses.

Our survey found that only 15.8 % of endoscopists use the resect-and-discard strategy in their current practice and 59.9 % thought that implementation was not feasible of the resect-and-discard strategy in its current form. The most important reasons why the resect-and-discard strategy was not feasible included fear of making an incorrect diagnosis leading to incorrect surveillance interval assignment and medicolegal issues. Our results were similar to those found by Soudagar et al. 2016, where medicolegal concerns were the main barrier for implementation of the resect-and-discard strategy for the 105 Gastroenterologists surveyed during a national conference in the United States 14 . These reasons seem to point towards a concern of potential interval CRCs when using a resect-and-discard strategy, however, 80.3 % of endoscopists voiced the opinion that a resect-and-discard strategy would not increase CRC risk. This could be caused by endoscopists feeling that interval cancer, while not more frequent with the resect-and-discard strategy, would be more difficult to explain in a possible future medicolegal pursuit. Very few endoscopists cited complexity of resect-and-discard and training requirements as barriers for implementation. While the consensus for most regions is that resect-and-discard was not feasible, European endoscopists showed an increased adoption of the strategy (54.3 %). Endoscopist practice can be dependent upon current healthcare culture, such as fear of medico-legal issues, acquiring new technology, and early adoption of new trends, which potentially explains the varying dispositions observed between geographic regions.

While the survey found that endoscopists did not completely trust their capacity to make accurate diagnoses, recent meta-analyses have shown that adequately trained endoscopists can achieve > 90 % concordance with histology-based diagnosis and > 90 % negative predictive value during optical diagnosis 8 9 . The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) currently recommend the use of resect-and-discard if these thresholds can be met. However other studies have shown that endoscopists can be unable to reach these benchmarks even after optical diagnosis training 10 15 16 . Most gastroenterology and endoscopy societies across the world have not yet officially made statements on resect-and-discard in their guidelines because of this contradictory data, contributing to the low implementation rate we found in this study. Further, recent research in imaging technologies and optical diagnosis have led to the emergence of many optical diagnosis-based classification systems, each with their own criteria, which can be confusing and overwhelming for endoscopists 17 . Our survey shows a definite concern from endoscopists about the feasibility of making optical diagnoses and highlights the need for simplifying decision-making or removing the need for optical diagnosis altogether 18 . A recent study has proposed a simplified and/or location-based strategy to reduce the need for optical diagnosis 19 . These simplified strategies achieved > 90 % surveillance interval agreement compared to pathology and allowed for providing more patients with surveillance interval planning on the same day as the colonoscopy 19 . Other recent studies have proposed using only number and size of polyps as criteria for surveillance interval assignment 20 21 . This approach was able to achieve a 90 % surveillance interval agreement with pathology in one instance and an 89.3 % agreement in another 20 21 . More than 80 % of patients could be provided with a surveillance interval on the same day using such an approach 20 21 . These alternative approaches thus appear promising even though endoscopists tended to prefer shorter intervals 20 . Limitations of simplified polyp (number and size only) or location-based strategies include the problem of not being able to distinguish between early signs of cancer (i. e. NICE-3 morphology) in optical diagnosis.

There was no consensus between endoscopists on cancer risk of diminutive polyps, with about 50 % believing that leaving them unresected increased cancer risk. This result differs from a survey by Gellad et al. 2013, which reported that the majority of respondents would be somewhat agreeable to leave diminutive polyps in place if guidelines would support this practice 22 . Half of endoscopists in our study believed that CT-colonography increased patient risk. Studies on CT-colonography performance show a sensitivity of > 90 % for the detection of polyps > 10 mm and > 95 % for the detection of colorectal cancer 23 24 25 . CT-colonography was, however, shown to have lower detection of high-risk SSAs when compared to colonoscopy 26 and exhibits poor sensitivity in diminutive polyp detection 27 . However, risk of malignancy of diminutive colon polyps was shown to be extremely low: 2 % having advanced histology, and approximately 0.05 % containing high grade dysplasia or neoplasia 1 2 . Studies with large numbers of small and diminutive polyps found no CRC present in any of these polyps 2 28 . Recent studies on the natural history of diminutive polyps showed a very indolent course for these polyps on follow-ups 29 30 . Current literature therefore suggests that risk of CRC arising from diminutive polyps is extremely low.

It is interesting to note that most endoscopists in our survey reported leaving polyps unresected in their patients and assigning 3- to 5-year maximum surveillance intervals when doing so. A recent meta-analysis has shown poor worldwide adherence for post-colonoscopy surveillance intervals 31 . Because resect-and-discard allows for providing more patients on the same day as the colonoscopy with a decision on when the next surveillance interval can be scheduled, clinical introduction of resect-and-discard might not only reduce immediate pathology costs but also upstream costs through avoiding unnecessary short follow-up surveillance intervals.

One important study limitation is the low response rate causing a potential for selection bias. However, since endoscopists can be members of multiple societies our response rate might be underestimated and represented a worst-case scenario. The advertising of our survey through Facebook/Twitter could also have skewed our sample towards younger endoscopists with more of an online presence or encourage double clicking from some of the participants. Furthermore, survey study always raise the issue of possible participation bias where survey participants are more incline to be up to date with recent guidelines and recommendations. Even in this selected population, resect-and-discard uptake was very low; suggesting the true uptake in the general population is probably even lower. The majority of responses were from the United States, Canada and Europe, which potentially limits our interpretation and generalizability to other regions. The survey was only available in English, which could have led to selection bias for certain regions of the world and for anglophone participants. However, we present the largest survey available to date on the topic.

Conclusion

In conclusion, current uptake of resect-and-discard is very low (15.8 %) with most endoscopists agreeing that such strategies are not feasible. Fear of making the wrong diagnosis and potential medicolegal repercussions are cited amongst the main reasons for difficulty of implementation. The development of simplified resect-and-discard models will likely provide a solution to these barriers for implementing resect-and-discard in clinical practise.

Acknowledgements

The findings, statements, and views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Competing interests Dr. von Renteln is supported by a “Fonds de Recherche du Québec Santé” career development award and has received research funding from ERBE, Ventage, Pendopharm and Pentax and is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Pendopharm.

Supplementary material :

References

- 1.Lieberman D, Moravec M, Holub J et al. Polyp size and advanced histology in patients undergoing colonoscopy screening: implications for CT colonography. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1100–1105. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta N, Bansal A, Rao D et al. Prevalence of advanced histological features in diminutive and small colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1022–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler W R, Imperiale T F, Klein R W et al. A quantitative assessment of the risks and cost savings of forgoing histologic examination of diminutive polyps. Endoscopy. 2011;43:683–691. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IJspeert J E, Bastiaansen B A, van Leerdam M E et al. Development and validation of the WASP classification system for optical diagnosis of adenomas, hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Gut. 2016;65:963–970. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewett D G, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y et al. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:599–INF. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iacucci M, Trovato C, Daperno M et al. Development and validation of the SIMPLE endoscopic classification of diminutive and small colorectal polyps. Endoscopy. 2018;50:779–789. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-100791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sano Y, Tanaka S, Kudo S E et al. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors proposed by the Japan NBI Expert Team. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:526–533. doi: 10.1111/den.12644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGill S K, Evangelou E, Ioannidis J P et al. Narrow band imaging to differentiate neoplastic and non-neoplastic colorectal polyps in real time: a meta-analysis of diagnostic operating characteristics. Gut. 2013;62:1704–1713. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abu Dayyeh B K, Thosani N, Konda V et al. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:502 e501–502 e516. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rex D K, Kahi C, O'Brien M et al. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaminski M F, Hassan C, Bisschops R et al. Advanced imaging for detection and differentiation of colorectal neoplasia: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2014;46:435–449. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health Care and Excellence Virtual chromoendoscopy to assess colorectal polyps during colonoscopy. Diagnostic Guidance [D628] 2017. Available at (Accessed May 4th 2019):https://www.nice.org/uk/guidance/dg28

- 13.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soudagar A S, Nguyen M, Bhatia A et al. Are gastroenterologists willing to implement the “predict, resect, and discard” management strategy for diminutive colorectal polyps? results from a national survey. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:e45–49. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGill S K, Soetikno R, Rastogi A et al. Endoscopists can sustain high performance for the optical diagnosis of colorectal polyps following standardized and continued training. Endoscopy. 2015;47:200–206. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1378096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vleugels J LA, Dijkgraaf M GW, Hazewinkel Y et al. Effects of training and feedback on accuracy of predicting rectosigmoid neoplastic lesions and selection of surveillance intervals by endoscopists performing optical diagnosis of diminutive polyps. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1682–1693 e1681. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djinbachian R, Dube A J, von Renteln D. Optical diagnosis of colorectal polyps: recent developments. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17:99–114. doi: 10.1007/s11938-019-00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkinson N S, East J E. Optical biopsy and sessile serrated polyps: Is DISCARD dead? Long live DISCARD-lite! Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Renteln D, Kaltenbach T, Rastogi A et al. Simplifying resect and discard strategies for real-time assessment of diminutive colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:706–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammar C, Frenn M, Pohl H et al. The polyp-based resect-and-discard strategy: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2019;51:OP262. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i19.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duong A, Bouin M, Leduc R et al. A7 The Polyp-based resect-and-discard strategy. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2019;2:15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gellad Z F, Voils C I, Lin L et al. Clinical practice variation in the management of diminutive colorectal polyps: results of a national survey of gastroenterologists. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:873–878. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson C D, Chen M-H, Toledano A Y et al. Accuracy of CT colonography for detection of large adenomas and cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1207–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halligan S, Altman D G, Taylor S A et al. CT colonography in the detection of colorectal polyps and cancer: systematic review, Meta-analysis, and proposed minimum data set for study level reporting. Radiology. 2005;237:893–904. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2373050176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickhardt P J, Hassan C, Halligan S et al. Colorectal cancer: CT colonography and colonoscopy for detection – systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2011;259:393–405. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ijspeert J EG, Tutein Nolthenius C J, Kuipers E J et al. CT-colonography vs. colonoscopy for detection of high-risk sessile serrated polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:516. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulhall B P, Veerappan G R, Jackson J L. Meta-analysis: computed tomographic colonography. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:635–650. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ponugoti P L, Cummings O W, Rex D K. Risk of cancer in small and diminutive colorectal polyps. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vleugels J LA, Hazewinkel Y, Fockens P et al. Natural history of diminutive and small colorectal polyps: a systematic literature review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1169–INF. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vleugels J LA, Hassan C, Senore C et al. Diminutive polyps with advanced histologic features do not increase risk for metachronous advanced colon neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:623–INF. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Djinbachian R, Dubé A-J, Durand M et al. Adherence to post-polypectomy surveillance guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2019;51:673–683. doi: 10.1055/a-0865-2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.