Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) released from cells play vital roles in intercellular communication. Moreover, EVs released from stem cells have therapeutic properties. This review confers the potential of brain-derived EVs in the cerebrospinal fluid and the serum as sources of epilepsy-related biomarkers, and the promise of mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs for easing status epilepticus-induced adverse changes in the brain. EVs shed from neurons and glia in the brain can also be found in the circulating blood as EVs cross the blood-brain barrier. Evaluation of neuron and/or glia-derived EVs in the blood of patients who have epilepsy could help in identifying specific biomarkers for distinct types of epilepsies. Such a liquid biopsy approach is also amenable for repeated analysis in clinical trials for comprehending treatment efficacy, disease progression, and mechanisms of therapeutic interventions. EV biomarker studies in animal prototypes of epilepsy, in addition, could help in identifying specific miRNAs contributing to epileptogenesis, seizures, or cognitive dysfunction in different types of epilepsy. Furthermore, intranasal administration of mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs after SE has shown efficacy for restraining SE-induced neuroinflammation, aberrant neurogenesis, and cognitive dysfunction in an animal prototype. Clinical translation of EV therapy as an adjunct to antiepileptic drugs appears attractive to counteract the progression of SE-induced epileptogenic changes, as the risk for thrombosis or tumor is minimal with nano-sized EVs. Also, EVs can be engineered to deliver specific miRNAs, proteins, or antiepileptic drugs to the brain since they incorporate into neurons and glia throughout the brain after intranasal administration.

Keywords: Cognitive Dysfunction, Extracelluar Vesicles, Exosomes, Memory, Mesenchymal Stem Cells, Seizures, Status Epilepticus, Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

INTRODUCTION

A variety of vesicles released by cells into the extracellular space are generically referred to as extracellular vesicles (EVs) [1]. EVs, found in all body fluids, are delimited by a phospholipid bilayer and contain nucleic acids and proteins from donor cells [2]. EVs partake in intercellular communication and likely also influence many cellular processes. Studies characterizing the composition of EVs in various body fluids have suggested that analysis of EVs from the serum or the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) could provide information on specific biomarkers in various neurodegenerative diseases. Investigation of EVs isolated from the serum or CSF has advantages because such characterization allows the analysis of the composition of EVs secreted from specific brain cells (e.g., EVs derived from neurons vis-à-vis astrocytes). Also, the configuration of EVs is likely more stable than soluble biomarkers found in the CSF or the serum.

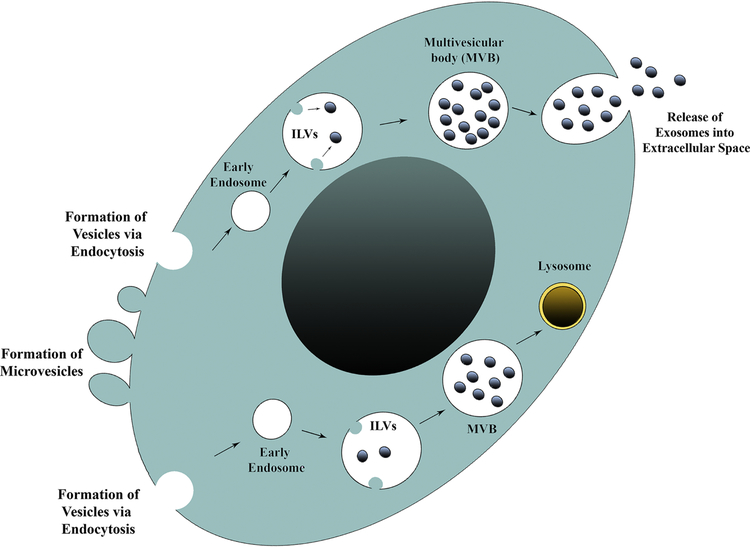

EVs are broadly classified as microvesicles (MVs) or exosomes (EXs) based on their intracellular origin. Microvesicles bud off from the plasma membrane and are rich in negatively charged phospholipids such as phosphatidylserine at their surface [2] (Fig. 1). The size of MVs can vary from 100–1000 nm [3]. The composition of MVs depends on the cell type from which they are generated and the type of stimulation causing their creation. However, proteins specific to MVs are yet to be identified [2]. In contrast, EXs originate in endosomes as intraluminal vesicles through inward invagination of the endosomal membrane, which eventually results in the formation of multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs) containing a constellation of exosomes (Fig. 1). While some MVBs fuse with lysosomes to degrade their cargo, others fuse with the plasma membrane to secrete EXs into the extracellular space [4] (Fig. 1). The creation of EXs, particularly the formation of intraluminal vesicles, requires the involvement of intricate protein machinery termed the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT). Nonetheless, the formation of EXs can also occur in an ESCRT-independent manner, which involves the participation of syndecan/syntenin/ALIX pathway [5]. Besides, CD9- and CD63-dependent pathways have also been implicated in EX formation [2, 6, 7]. The EXs exhibit well-demarcated round morphology and their size can vary from 30–150 nm, depending on the type of cells from which they are released [8–11]. While the kinetics, the composition and the biological properties of EXs vary significantly in health and disease conditions [12], EXs from various sources have been isolated, characterized, and customized for specific applications. Analyses of the composition of EXs derived from multiple sources have implied that EXs are rich in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids derived from their parental cells.

Figure 1 –

A cartoon showing the formation and shedding of microvesicles and exosomes from a cell. Microvesicles bud off directly from the plasma membrane. Conversely, exosomes originate in endosomes as intraluminal vesicles through inward invagination of the endosomal membrane, which eventually results in the formation of multi-vesicular bodies (MVBs) comprising a collection of exosomes. Some MVBs fuse with lysosomes and exosomes and their cargo are degraded. See the example in the lower right side of the nucleus. The other MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane and secrete exosomes into the extracellular space. An example is illustrated in the top part of the cell.

The details on the composition of proteins, lipids, and RNA in EVs or EXs can be seen in three different web-based resources, either at http://www.exocarta.org/ or Vesiclepedia.or EVpedia. These databases suggest frequently observed protein components in EVs and EXs, which include annexins, cytoskeletal proteins, heat shock proteins, integrins, metabolic enzymes, ribosomal proteins, tetraspanins, and vesicle trafficking-related proteins [13]. The major lipid components of EXs derived from various cells are recently reviewed [14] which includes cholesterol, sphingomyelin, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylethanolamine ethers, diacylglycerol, phosphatidylcholine ethers, hexosyl ceramide, ceramides, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidic acid, phosphatidylinositol, lactosylceramide, lysophosphatidylinositol, lysophosphatidylethanolamine, cholesteryl ester, globotriaosylceramide, etc [14]. The nucleic acids in EXs comprise mRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs), and other non-coding RNAs. While the composition of EXs varies depending on the type of cell from which EXs released, the exact mechanism by which a variety of molecules are loaded into EXs is still unknown. Interestingly, the protein composition of EXs is more likely to be different from their mother cells than the protein composition in MVs [15]. Moreover, EXs tend to be enriched with proteins of extracellular matrix, heparin-binding receptors, and immune response and cell adhesion functions. Conversely, MVs are enriched with proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum, proteasome, and mitochondria [2]. Following their release by donor cells, EXs can enter recipient cells, influence their function by activating intracellular signaling pathways through the transfer of their cargo. The uptake of EXs or its cargo by recipient cells can occur through several mechanisms. For instance, endocytosis of EXs depends on caveolae in epithelial cells [16], clathrin in neurons [17], and cholesterol and lipid raft in endothelial cells [18]. The incorporation of EXs by microglia and macrophages involves macropinocytosis [19] or phagocytosis [20].

Since the size range of MVs and EXs overlap, a rigorous characterization of EV properties are necessary for classifying them as either MVs or EXs. Initially, evaluation of at least three specific markers was considered essential to classify EVs as EXs [21]. The markers include tetraspanins CD9, CD63, CD81, the endosomal proteins tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101), and ALG-2-interacting protein X (ALIX). Because some of these markers can also be found in MVs [22], recent guidelines from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) suggest the use of operational terms unless the release of EXs by cells is caught in the act through live imaging techniques. The suggested operational terms are based on physical characteristics of EVs such as the size (small EVs, medium/large EVs), biochemical composition (e.g., CD63+/CD81+−/CD9+− EVs) or cells of origin (e.g., neuron-derived EVs, astrocyte-derived EVs, or microglia-derived EVs) [1]. Therefore, we employed the phrase “EVs” for all EV or EX studies discussed in this review in the subsequent sections.

The goal of this article is to confer two specific issues about EVs. The first segment of the review deliberates the potential of EVs in body fluids, particularly in the serum and the CSF, as sources of specific epilepsy biomarkers. The second part of the review confers the promise of mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs for treating status epilepticus-induced brain dysfunction and chronic epilepsy.

Potential of EVs as biomarkers of epilepsy

Several disease-specific proteins and/or miRNAs are enriched in EVs shed from neurons or glia into the blood or the CSF. Therefore, evaluation of the composition of EVs released into the plasma or the CSF by neurons and glia in the central nervous system (CNS) can provide diagnostic and/or prognostic insights on brain function particularly in neurological disorders [2, 23]. Especially, neuron-, astrocyte-, oligodendrocyte- and microglia-derived EVs (NDEVs, ADEVs, ODEVs, MDEVs) in the serum or the CSF are considered a valuable source for the detection of early markers of CNS diseases, including neurodevelopmental disorders [24–28]. Some of the notable biomarkers in neurological disorders observed through analysis of EVs include the enrichment of phosphorylated tau (p-tau) at Thr-181 relative to total tau in the early stages of the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [29], higher levels of cathepsin D, and Lamp-1 proteins in NDEVs, ~10 years before the diagnosis of AD [30, 31], and higher levels of alpha-synuclein in patients with Parkinson’s disease [32]. Moreover, periodic characterization of NDEVs in the plasma of patients with mild cognitive impairment may provide insights on the probability of MCI progressing into dementia [33]. Likewise, the characterization of EVs from dementia patients could be useful for distinguishing frontotemporal dementia (FTD) from AD [27].

Furthermore, specific analysis of miRNAs in EVs has received considerable interest in the diagnosis and prognosis of neurological diseases due to their higher stability over mRNAs [34, 35]. miRNAs are tiny, noncoding RNA fragments involved in controlling gene expression in a post-transcriptional manner through binding to matching strings in mRNA [36]. Like other EVs, brain-derived EVs are also enriched with multiple miRNAs, characterization of which may provide insights on brain function or the progression of a disease (25, 26, 28]. Typically, miRNA levels in EVs isolated from the CSF or plasma are higher than their concentration in the non-exosomal supernatant fractions following centrifugation [28]. Thus, characterization of miRNAs and other biomarkers in NDEVs, ADEVs, ODEVs and MDEVs isolated from the plasma or the CSF is far superior to measuring their levels in the plasma or CSF itself. Still, it should be noted that the miRNA content of CNS-derived EVs isolated from the CSF may not perfectly match the miRNA content of CNS-derived EVs isolated from the plasma. For instance, miRNAs that are particularly rich in the brain such as miR-1911–5p are seen in CNS-derived EVs in the CSF but not in CNS-derived EVs in the serum [28]. Such finding suggests that periodic analysis of CNS-derived EVs from both CSF and the plasma may be necessary for the optimal diagnosis of certain neurological disorders. Nonetheless, increased expression of a specific miRNA or a group of miRNAs in CNS-derived EVs isolated from either the CSF or the plasma may provide essential insights on the progression of diseases afflicting the CNS.

There have been only a few studies hitherto on the potential biomarkers of epilepsy that can be gleaned from the analysis of EVs in the blood or the CSF. Epilepsy affects ∼60 million people worldwide, and nearly 1% Americans [37]. Approximately 30% of epileptic patients have temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) typified by the progressive development of complex partial seizures, hippocampal neurodegeneration, and co-morbidities such as cognitive and mood impairments. Status epilepticus (SE) is a life-threatening medical and neurological emergency that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment, otherwise leading to significant morbidity and mortality [38]. As per the new definition, SE is a single epileptic seizure lasting more than five minutes or two or more seizures in five-minutes without the person returning to normal between them. It is well known that SE could lead to lasting brain dysfunction through epileptogenic changes, leading to chronic epilepsy. Recently, a study by Raoof and colleagues examined the potential of miRNAs isolated from the CSF in aiding differential diagnosis of TLE and SE from other neurological diseases [39]. In the miRNA profiling phase, the CSF from control and TLE samples displayed similar numbers of miRNAs (43–56 miRNAs/sample) while CSF from SE patients demonstrated a significantly higher number of miRNAs (74/sample). There was considerable overlap in terms of the occurrence of miRNAs in EVs isolated from the CSF of TLE and SE patients, but levels of some miRNAs varied considerably between TLE and SE samples. In comparison to controls, TLE samples showed elevated levels of miR-19b-3p and three other miRNAs, and diminished levels of 7 different miRNAs. On the other hand, EVs from SE samples showed elevated levels of miR-21–5p, miR-451a, and six other miRNAs, and downregulation of miR-204–5p.

To analyze miRNAs levels complexed to Argonaute 2 or packaged in EVs, Raoof et al. (2017) separately extracted total RNA and RNAs from Argonaute 2 and EVs from the CSF. Argonaute 2, a protein found in the RNA-induced silencing complex, binds to miRNAs and guides miRNAs to target mRNAs resulting in either degradation of mRNAs or a reduction in translation to proteins [40]. Separate analyses of the levels of miR-19b-3p, miR-21–5p and miR-451a complexed to Argonaute 2 or present in EVs relative to the total miRNA content in CSF uncovered that miRNAs show a unique pattern of distribution between Argonaute 2 and EVs. Remarkably, the best miRNA biomarker of TLE, miR-19b-3p, was mostly found as Argonaute 2 bound in TLE and SE patients, in contrast to AD where this miRNA was found mostly in EVs isolated from the CSF. However, miR-21–5p in SE and miR-451a in TLE samples were packaged mostly to EVs [39]. Moreover, calculation of area under the curve (AUC) following ROC curve analysis using binomial logistic regression showed that AUC was higher when the EV miRNA was used versus Argonaute 2 miRNA indicating that miRNAs within EVs in CSF samples accurately reflect the pathophysiology of TLE or SE [39]. A follow-up study, performing miRNA analysis in plasma from a larger cohort of samples (>250) from two countries using two different genome-wide screening platforms, identified miR-27a-3p,miR-328–3p and miR-654–3p as potential biomarkers for epilepsy. This study was also validated with plasma samples from patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures who would often be mistaken for epilepsy [41]. In the EV enriched fraction of the plasma, all of these biomarkers were found at higher levels, which may imply that in the epileptic brain, miRNAs are mostly loaded into EVs rather than transported through Argonaute 2 bound form. Besides, combined levels of miR-27a-3p, miR-328–3p and miR-654–3p in EVs achieved an AUC of 0.93, which is excellent for a biomarker, suggesting the validity of these miRNA levels in EVs as potential biomarkers of epilepsy.

Another study by Yan and colleagues evaluated miRNAs in plasma-derived EVs from 40 patients diagnosed with mesial TLE with hippocampal sclerosis (mTLE-HS) and 40 gender and age-matched healthy volunteers [42]. All 40 patients included were referred for surgical resection of the hippocampus due to medically intractable epilepsy, and all were evaluated by neurological assessment, video EEG recordings, and MRI neuroimaging. The presence of hippocampal sclerosis was confirmed through postoperative pathological analysis. Characterization of plasma EV miRNAs in these patients in comparison to healthy controls revealed differential expression of over 50 miRNAs. In EVs from mTLE-HS patients, elevated expression was seen for miR-3613–5p (~11 fold increase) and miR-6511b (~2 fold increase) with 48 other miRNAs showing downregulation. Among the significantly decreased EV miRNAs, 6 candidate miRNAs were validated based on their possible involvement in seizure development in mTLE-HS, which include miR-4668–5p, miR-3613–5p, miR-8071, miR-197–5p, miR-4322, and miR-6781–5p (2–10 increase). Among these miRNAs, plasma EV miR-8071 was considered as a key diagnostic marker for mTLE-HS due to its 83.3% sensitivity and 96.7% specificity for the disease. Also, miR-8071 was well-associated with seizure severity.

Thus, the characterization of brain-derived EVs in the CSF and/or plasma has the promise to identify useful biomarkers in different types of epilepsies. Characterization of specific miRNAs and proteins in NDEVs, ADEVs, MDEVs in the CSF and/or plasma of epileptic patients may further help in identifying the occurrence or progression of explicit neuropathology predominantly seen in specific types of epilepsy. Furthermore, it is unknown whether NDEVs, ADEVs or MDEVs are involved in the propagation of hyperexcitability, seizures, or neuropathology from one region to another region of the brain in epileptic conditions. In conditions such as AD, NDEVs are involved in the propagation of the disease in the brain. Also, exogenous administration of NDEVs from patients diagnosed with a more advanced stage of AD into naïve mice resulted in increased phosphorylation of tau (a hallmark of AD) [33]. It remains to be examined whether exogenous administration of NDEVs, ADEVs or MDEVs from chronically epileptic patients/animals would cause hyperexcitability, seizures, or neuroinflammation in naive animals. Also, the possibility of NDEVs, ADEVs, or MDEVs from chronically epileptic patients carrying a cargo of anticonvulsant miRNAs and proteins cannot be ruled out.

Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs for modulating brain dysfunction after SE or in chronic epilepsy

Multiple studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived EVs, for treating neurological conditions such as stroke [43], ischemia [44], traumatic brain injury (10, 45], hypoxic-ischemia induced perinatal brain injury [46, 47], pre-term brain injury [48], multiple sclerosis [49], AD [50], spinal cord injury [51]. Kim and colleagues investigated the efficacy of human MSC-derived EVs in a controlled cortical impact injury model [10]. EVs employed in this investigation were derived from hMSCs using chromatographic procedures and validated for robust antiinflammatory activity in a lipopolysaccharide-induced systemic inflammation mouse model before their use. Intravenous administration of EVs an hour after the induction of CCI was efficient for suppressing the early surge of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1beta (IL-1b) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) in the mouse hippocampus. Such robust antiinflammatory effect of EVs early after TBI was adequate for rescuing both pattern separation and spatial learning impairments seen after TBI [10]. Thus, MSC-derived EVs have promise for treating neurological disorders that exhibit significant neuroinflammation.

An episode of status epilepticus causes neurodegeneration as well as acute neuroinflammation. These initial adverse effects progress into chronic neuroinflammation and the occurrence of spontaneous seizures. Therefore, administration of MSC-derived EVs into the brain immediately after SE or after the development of chronic epilepsy is likely to be beneficial for modulating inflammation-related brain impairments, which may include cognitive dysfunction and spontaneous seizures. Indeed, patients experiencing SE have an increased risk of developing chronic epilepsy and cognitive problems. Chronic inflammation in the hippocampus and related limbic regions after SE-induced neurodegeneration is believed to be one of the primary factors contributing to functional deficits. Disruption of the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) and neurodegeneration serve as triggers for the onset of acute inflammation after SE [52]. Acute inflammation in the first few days after SE in the hippocampus in animals models is apparent through a “cytokine storm,” typified by upregulation of multiple proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [53, 54]. Moreover, enhanced concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines are continuously observed in the epileptic hippocampus and are believed to be derived from activated microglia/macrophages and reactive astrocytes [55–57]. Thus, early antiinflammatory interventions after SE seem critical for preserving normal hippocampal function [57].

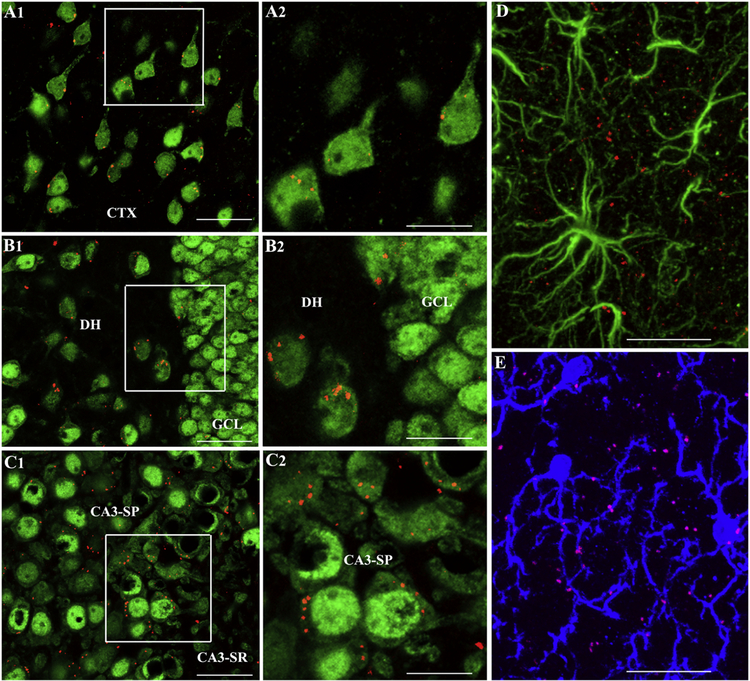

Intranasal (IN) administration of hMSC-derived EVs twice within 24 hours after SE in a mouse pilocarpine model efficiently blocked “cytokine storm” in the hippocampus [54]. Blockage of cytokine storm was evidenced by normalized levels of multiple proinflammatory proteins including TNF-a and IL-1b and increased concentration of the antiinflammatory protein IL-10 in the hippocampus. Nevertheless, it remains to be investigated whether EVs mediate these effects through the release of antiinflammatory proteins into the extracellular space, by counteracting seizure-induced cellular stress in neurons through direct incorporation into vulnerable neurons or via modulation of activated microglia and reactive astrocytes. Each of this possibility is likely because EVs can get incorporated into hippocampal neurons and microglia and stay in close contact with astrocytic processes in the hippocampus within 6 hours of IN administration in this study [54]. Additional studies on inflammatory signaling pathways will be needed to comprehend mechanisms underlying EV-mediated suppression of acute inflammation after SE, however. IN administration of EVs after SE also provided robust neuroprotection, which was evinced through reduced neuronal loss in the DH and CA1 cell layers as well as the preservation of parvalbumin- and somatostatin-positive GABA-ergic interneurons [54]. Neuroprotective effects may reflect a consequence of strong antiinflammatory effects of EVs. Some direct impact through the release of neurotrophic factors or antioxidant proteins cannot be ruled out since neurons internalized EVs in the dentate hilus, the granule cell layer and CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cell layers [54]. Additional studies are needed in the future whether this neuroprotection is enduring and whether the extent of protection of GABA-ergic interneurons is adequate for preventing the occurrence of spontaneous recurrent seizures. IN administration of EVs after SE also maintained a standard pattern and extent of neurogenesis when examined ~8 weeks after SE [54]. Reelin+ interneurons were rescued with reduced numbers of Prox-1+ granule cells in the DH of animals receiving EVs after SE, implying that the protection of reelin+ interneurons mediated by EVs underlies the diminished abnormal migration of newly born neurons. The preservation of the typical extent of neurogenesis is likely linked to enduring suppression of neuroinflammation. Indeed, microglia in the hippocampus of EV-treated animals displayed normal morphology with ramified processes and the absence of hypertrophied soma. It is plausible that much-restrained neuroinflammation mediated by IN administered EVs reduced the potential loss of neural stem cells (NSCs) as well as curbed adverse changes in the milieu of NSCs after SE. Such beneficial effects likely promoted a standard proliferative behavior of NSCs to maintain neurogenesis at levels seen in age-matched controls. Long-term studies are needed to determine whether neurogenesis and NSC behavior stay normal for protracted periods and whether the pattern of neurogenesis becomes abnormal if some spontaneous recurrent seizures emerge at later time-points.

Status epilepticus also leads to deficiencies in recognition and location memories and pattern separation ability (54, 58, 59]. Remarkably, IN administration of EVs after SE maintained recognition memory and pattern separation function when examined ~6 weeks after SE. The ability for recognition and location memories and pattern separation are interconnected to the integrity of the hippocampal trisynaptic pathway and/or hippocampal neurogenesis. From this perspective, EV-mediated protection of glutamatergic and GABA-ergic neurons, as well as the maintenance of standard neurogenesis, played roles in the preservation of hippocampus-dependent function [60, 61]. Inhibition of inflammation enabled by EVs has possibly also helped this cause. Nonetheless, it remains to be investigated whether learning, memory and mood function remain normal at 6–8 months post-SE, as slowly-evolving epileptogenic changes may emerge in a delayed fashion because antiinflammatory EVs were administered only during the immediate post-SE period. Additional studies may also determine whether repeated administration of EVs in acute and/or latent phases will be required to maintain seizure-free status and standard memory and mood function at extended time-points after SE. The overall results from the study suggest that hMSC-EVs may be used clinically as an adjunct to AED therapy after SE to block or reduce the progression of epileptogenic changes as well as in chronic epilepsy. The efficacy of EVs to improve cognitive function and/or suppress spontaneous seizures in chronic epileptic conditions is yet to be investigated, however. Additionally, it remains to be addressed whether IN administration of EVs is efficacious for modulating abnormal long-term plasticity such as aberrant mossy fiber sprouting [62–64], the activation of mTOR pathway [65–67] or psychiatric comorbidities [58, 59] associated with epilepsy.

Summary and future perspectives

EVs are enriched with miRNAs, in comparison to non-EV fractions in the CSF or plasma. Since many studies have confirmed the occurrence of higher miRNA levels in EVs, characterization of CNS-derived EVs such as NDEVs, ADEVs, ODEVs or MDEVs from the CSF and/or plasma for miRNA expression appears highly useful for biomarker discovery in various types of epilepsy. Notably, analysis of NDEVs in the serum has received considerable attention for evaluating brain biomarkers in various CNS diseases as they can be obtained through a non-invasive approach (30, 31, 67–72]. Such a liquid biopsy approach is amenable for repeated analysis in clinical trials for understanding the efficacy of treatment, the progression of the disease, and molecular mechanisms of experimental interventions. Accordingly, analyses of NDEVs and ADEVs in serum samples of patients afflicted with various types of epilepsy with samples from age-matched controls and patients with other neurological diseases would likely help in identifying more accurate and specific biomarkers to distinct types of human epilepsies. Furthermore, EV biomarker studies using various animal models of epilepsy could help in identifying particular miRNAs contributing to spontaneous seizures, neuroinflammation, or cognitive function in different phases and types of epilepsy.

Furthermore, IN administration of hMSC-derived EVs after SE appears promising based on a study in an animal model, where EV intervention considerably restrained SE-induced neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation, aberrant neurogenesis, and cognitive and memory impairments. These outcomes are promising and imply that such a procedure may be used clinically as an adjunct to AED therapy after SE to counteract epileptogenic modifications from progressing into a chronic epileptic state. There are many advantages of using EVs. They can be engineered to package specific mRNAs, miRNAs, and proteins. EVs can easily cross the BBB and deliver various therapeutic factors to the brain [73]. They possess minimal risks, as they are unlikely to cause thrombosis or tumors because of their size ranging from 30–150 nm and lack of proliferation ability. Nevertheless, further studies are critical at protracted time-points after SE to characterize whether the magnitude of antiinflammatory, neuroprotective, neurogenic, cognitive and memory-protective outcomes facilitated by these EVs are enough to avert the advancement of SE-induced initial precipitating injury into a chronic epileptic state. Also, evaluating the beneficial effects of EVs from other cell sources such as neural stem cells or astrocytes could further improve the therapeutic outcome as EVs from such brain-derived cells have been shown to promote antiinflammatory and neurogenic effects [74–75]. They may also carry anticonvulsant molecules or miRNAs that may activate endogenous signaling pathways promoting anticonvulsant activity. Besides, EVs may also be used to deliver antiepileptic drugs to neurons, as EVs not only reach virtually all regions of the brain within 6 hours after IN administration but also get easily incorporated into neurons [76]. Development of a nasal spray of EVs loaded with specific AEDs in the future may curb neuroinflammation as well as help to reduce the daily dose of currently used AEDs without losing effectiveness for controlling seizures.

Figure 2 –

Intranasally dispensed PKH26-labeled extracellular vesicles (EVs) invade virtually all regions of the brain within 6 hours after the administration. Figures A1-C2 show the presence of PKH26+ exosomes (red dots) within the cytoplasm or in close contact with the cell membrane of neuron-specific nuclear antigen-positive (NeuN+) neurons in the cerebral cortex (A1), the dentate hilus and granule cell layer (B1) and CA3 pyramidal neurons (C1) of the hippocampus when examined 6 hours after their intranasal administration. A2, B2 and C2 show magnified views of boxed regions in A1, B1, and C1. Figure D shows a lack of exosomes within the soma of glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive (GFAP+) astrocytes but the presence of some exosomes adjacent to astrocyte processes. Figure E demonstrates the presence of exosomes within the soma or processes of some IBA-1+ microglia. CA3-SP, CA3 stratum pyramidale; CA3-SR, CA3 stratum radiatum; CTX, cortex; DH, dentate hilus; GCL, granule cell layer. Scale bar, A1,B1,C1 = 50 µm; A2,B2,C2 = 25 µm D,E = 25 µm. Figure reproduced from Long et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Apr 25;114(17):E3536-E3545.

Highlights.

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) released from cells play key roles in intercellular communication.

Evaluation of brain-derived EVs in the blood may help in identifying biomarkers for distinct types of epilepsies

Investigation of brain-derived EVs in the blood could help in identifying miRNAs involved in epileptogenesis

EVs released from mesenchymal stem cells have therapeutic properties

Stem cell-derived EV therapy appears attractive for counteracting epileptogenic changes after SE

EVs can be engineered to deliver specific miRNAs, proteins or antiepileptic drugs to the brain

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors are supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R01NS106907–01 to DJP and AKS), the Department of Defense (W81XWH-14–1-0558 to A.K.S.), the State of Texas (Emerging Technology Fund to A.K.S.), and Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB -EMR/2017/005213 to DU).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles 2018; 7: 1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malloci M, Perdomo L, Veerasamy M, Andriantsitohaina R, Simard G, Martinez MC. Extracellular vesicles: mechanisms in human health and disease. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2019; 30: 813–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flamant S, Tamarat R. Extracellular vesicles and vascular injury: new insights for radiation exposure. Radiat Res 2016; 186: 203–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 2013; 200: 373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baietti MF, Zhang Z, Mortier E, Melchior A, Degeest G, Geeraerts A, et al. Ivarsson Y, Depoortere F, Coomans C, Vermeiren E, Zimmermann P, and David G Syndecansyntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat Cell Biol 2012; 14: 677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buschow SI, Nolte-’t Hoen ENM, Van Niel G, Pols MS, Ten Broeke T, Lauwen M, et al. MHC II in Dendritic cells is targeted to lysosomes or T cell-induced exosomes via distinct multivesicular body pathways. Traffic 2009; 10: 1528–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Niel G, Charrin S, Simoes S, Romao M, Rochin L, Saftig P, et al. The tetraspanin CD63 regulates ESCRT-independent and dependent endosomal sorting during melanogenesis. Dev Cell 2011; 21: 708–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan B-T, Teng K, Wu C, Adam M, Johnstone RM. Electron microscopic evidence for externalization of the transferrin receptor in vesicular form in sheep reticulocytes. J Cell Biol 1985; 101: 942–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DK, Nishida H, An SY, Shetty AK, Bartosh TJ, Prockop DJ. Chromatographically isolated CD63+CD81+ extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stromal cells rescue cognitive impairments after TBI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113: 170–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durcin M, Fleury A, Taillebois E, Hilairet G, Krupova Z, Henry C, et al. Characterisation of adipocyte-derived extracellular vesicle subtypes identifies distinct protein and lipid signatures for large and small extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles 2017; 6: 1305677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Toro J, Herschlik L, Waldner C, Mongini C. Emerging roles of exosomes in normal and pathological conditions: new insights for diagnosis and therapeutic applications. Front Immunol 2015; 6:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathivanan S, Simpson RJ. ExoCarta: A compendium of exosomal proteins and RNA. Proteomics 2009; 9: 4997–0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skotland T, Sandvig K, Llorente A. Lipids in exosomes: Current knowledge and the way forward. Prog Lipid Res 2017; 66: 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haraszti RA, Didiot M-C, Sapp E, Leszyk J, Shaffer SA, Rockwell HE et al. High-resolution proteomic and lipidomic analysis of exosomes and microvesicles from different cell sources. J Extracell Vesicles 2016; 5: 32570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nanbo A, Kawanishi E, Yoshida R, and Yoshiyama H. Exosomes derived from Epstein-Barr virus-infected cells are internalized via Caveola-dependent endocytosis and promote phenotypic modulation in target cells. J Virol 2013; 87: 10334–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frühbeis C, Fröhlich D, Kuo WP, Amphornrat J, Thilemann S, Saab AS, et al. Neurotransmitter-triggered transfer of exosomes mediates oligodendrocyte-neuron communication. PLoS Biol 2013; 11: e1001604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Svensson KJ, Christianson HC, Wittrup A, Bourseau-Guilmain E, Lindqvist E, Svensson LM, et al. Exosome uptake depends on ERK1/2-heat shock protein 27 signaling and lipid raft-mediated endocytosis negatively regulated by caveolin-1. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 17713–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzner D, Schnaars M, van Rossum D, Krishnamoorthy G, Dibaj P, Bakhti M, et al. Selective transfer of exosomes from oligodendrocytes to microglia by macropinocytosis. J Cell Sci 2011; 124: 447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng D, Zhao W-L, Ye Y-Y, Bai X-C, Liu R-Q, Chang LF, et al. Cellular internalization of exosomes occurs through phagocytosis. Traffic 2010; 11: 675–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lötvall J, Hill AF, Hochberg F, Buzás EI, Di Vizio D, Gardiner C, et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles 2014; 3: 26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, Jouve M, Morath JP, Primdal-Bengtson B, et al. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113: E968–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanninen KM, Bister N, Koistinaho J, and Malm T. Exosomes as new diagnostic tools in CNS diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016; 1862: 403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiasserini D, van Weering JR, Piersma SR, Pham TV, Malekzadeh A, Teunissen CE, et al. Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles: a comprehensive dataset. J Proteomics 2014; 106:191–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Romero N, Carrión-Navarro J, Esteban-Rubio S, Lázaro-Ibáñez E, Peris-Celda M, Alonso MM, et al. DNA sequences within glioma-derived extracellular vesicles can cross the intact blood-brain barrier and be detected in peripheral blood of patients. Oncotarget 2017; 8) :1416–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham EM, Burd I, Everett AD, Northington FJ. Blood Biomarkers for Evaluation of Perinatal Encephalopathy. Front Pharmacol 2016; 7: 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goetzl EJ, Kapogiannis D, Schwartz JB, Lobach IV, Goetzl L, Abner EL, et al. Decreased synaptic proteins in neuronal exosomes of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J 2016; 30: 4141–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yagi Y, Ohkubo T, Kawaji H, Machida A, Miyata H, Goda S, et al. Next-generation sequencing-based small RNA profiling of cerebrospinal fluid exosomes. Neurosci Lett 2017; 636: 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saman S, Kim W, Raya M, Visnick Y, Miro S, Saman S, et al. Exosome-associated tau is secreted in tauopathy models and is selectively phosphorylated in cerebrospinal fluid in early Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 3842–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goetzl EJ, Boxer A, Schwartz JB, Abner EL, Petersen RC, Miller BL, et al. Altered lysosomal proteins in neural-derived plasma exosomes in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2015; 85: 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mustapic M, Eitan E, Werner JK Jr, Berkowitz ST, Lazaropoulos MP, Tran J, et al. Plasma Extracellular Vesicles Enriched for Neuronal Origin: A Potential Window into Brain Pathologic Processes. Front Neurosci 2017, 11: 278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi M, Liu C, Cook TJ, Bullock KM, Zhao Y, Ginghina C, et al. Plasma exosomal a-synuclein is likely CNS-derived and increased in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 2014; 128: 639–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winston CN, Goetzl EJ, Akers JC, Carter BS, Rockenstein EM, Galasko D, et al. Prediction of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia with neuronally derived blood exosome protein profile. Alzheimers Dement 2016; 3: 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung M, Schaefer A, Steiner I, Kempkensteffen C, Stephan C, Erbersdobler A, et al. Robust microRNA stability in degraded RNA preparations from human tissue and cell samples. Clin Chem 2010; 56: 998–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahraman M, Laufer T, Backes C, Schrörs H, Fehlmann T, Ludwig N, et al. Technical Stability and Biological Variability in MicroRNAs from Dried Blood Spots: A Lung Cancer Therapy-Monitoring. Showcase. Clin Chem 2017; 63: 1476–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004; 116: 281–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jobst BC, Cascino GD. Resective epilepsy surgery for drug-resistant focal epilepsy: a review. JAMA 2015; 313: 285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Mufti F, Claassen J. Neurocritical care: status epilepticus review. Crit Care Clin 2014; 30: 751–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raoof R, Jimenez-Mateos EM, Bauer S, Tackenberg B, Rosenow F, Lang J, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid microRNAs are potential biomarkers of temporal lobe epilepsy and status epilepticus. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Höck J, Meister G. The Argonaute protein family. Genome Biol 2008; 9: 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raoof R, Bauer S, El Naggar H, Connolly NMC, Brennan GP, Brindley E, et al. Dual-center, dual-platform microRNA profiling identifies potential plasma biomarkers of adult temporal lobe epilepsy. EBioMedicine 2018; 38: 127–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan S, Zhang H, Xie W, Meng F, Zhang K, Jiang Y, et al. Altered microRNA profiles in plasma exosomes from mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 4136–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xin H, Li Y, Cui Y, Yang JJ, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells promote functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity after stroke in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 1711–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doeppner TR, Herz J, Gorgens A, Schlechter J, Ludwig AK, Radtke S, et al. Extracellular Vesicles Improve Post-Stroke Neuroregeneration and Prevent Postischemic Immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl Med 2015; 4: 1131–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang., Chopp M, Meng Y, Katakowski M, Xin H, Mahmood A, et al. Effect of exosomes derived from multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg 2015; 122, 856–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ophelders DR, Wolfs TG, Jellema RK, Zwanenburg A, Andriessen P, Delhaas T, et al. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Protect the Fetal Brain After Hypoxia-Ischemia. Stem Cells Transl Med 2016; 5: 754–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sisa C, Kholia S, Naylor J, Herrera Sanchez MB, Bruno S, Deregibus MC, et al. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Derived Extracellular Vesicles Reduce Hypoxia-Ischaemia Induced Perinatal Brain Injury. Front Physiol 2019; 10: 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drommelschmidt K, Serdar M, Bendix I, Herz J, Bertling F, Prager S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate inflammation-induced preterm brain injury. Brain Behav Immun 2017; 60: 220–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laso-García F, Ramos-Cejudo J, Carrillo-Salinas FJ, Otero-Ortega L, Feliú A, Gómez-de Frutos M, et al. Therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles derived from human mesenchymal stem cells in a model of progressive multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0202590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang SS, Jia J, Wang Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Suppresses iNOS Expression and Ameliorates Neural Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. J Alzheimers Dis 2018; 61: 1005–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou X, Chu X, Yuan H, Qiu J, Zhao C, Xin D. Mesenchymal stem cell derived EVs mediate neuroprotection after spinal cord injury in rats via the microRNA-21–5p/FasL gene axis. Biomed Pharmacother 2019; 115: 108818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gorter JA, van Vliet EA, Aronica E. Status epilepticus, blood-brain barrier disruption, inflammation, and epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Behav 2015; 49, 13–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Costa-Ferro ZS, Souza BS, Leal MM, Kaneto CM, Azevedo CM, da Silva IC, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells decreases seizure incidence, mitigates neuronal loss and modulates pro-inflammatory cytokine production in epileptic rats. Neurobiol Dis 2012; 46:302–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Long Q, Upadhya D, Hattiangady B, Kim DK, An SY, Shuai B, et al. Intranasal MSC-derived A1-exosomes ease inflammation, and prevent abnormal neurogenesis and memory dysfunction after status epilepticus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017; 114: E3536–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hattiangady B, Kuruba R, Shetty AK. Acute seizures in old age leads to a greater loss of ca1 pyramidal neurons, an increased propensity for developing chronic tle and a severe cognitive dysfunction. Aging Dis 2011; 2: 1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prinz M, Priller J. Microglia and brain macrophages in the molecular age: from origin to neuropsychiatric disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014; 15, 300–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vezzani A, Friedman A, Dingledine RJ. The role of inflammation in epileptogenesis. Neuropharmacology 2013; 69, 16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shetty AK. Hippocampal injury-induced cognitive and mood dysfunction, altered neurogenesis, and epilepsy: can early neural stem cell grafting intervention provide protection? Epilepsy Behav 2014; 38: 117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Upadhya D, Hattiangady B, Castro OW, Shuai B, Kodali M, Attaluri S, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived MGE cell grafting after status epilepticus attenuates chronic epilepsy and comorbidities via synaptic integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019; 116: 287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mendelsohn AR, Larrick JW. Pharmaceutical Rejuvenation of Age-Associated Decline in Spatial Memory. Rejuvenation Res 2016; 19: 521–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryan SM, Nolan YM. Neuroinflammation negatively affects adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognition: can exercise compensate? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016; 61, 121–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shetty AK, Turner DA. Aging impairs axonal sprouting response of dentate granule cells following target loss and partial deafferentation. J Comp Neurol 1999; 414: 238–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shetty AK, Zaman V, Hattiangady B. Repair of the injured adult hippocampus through graft-mediated modulation of the plasticity of the dentate gyrus in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci 2005; 25:8391–8401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hattiangady B, Rao MS, Zaman V, Shetty AK. Incorporation of embryonic CA3 cell grafts into the adult hippocampus at 4-months after injury: effects of combined neurotrophic supplementation and caspase inhibition. Neurosci 2006; 139: 1369–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hester MS, Hosford BE, Santos VR, Singh SP, Rolle IJ, LaSarge CL, Liska JP, Garcia-Cairasco N, Danzer SC. Impact of rapamycin on status epilepticus induced hippocampal pathology and weight gain. Exp Neurol 2016; 280: 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X, Sha L, Sun N, Shen Y, Xu Q. Deletion of mTOR in Reactive Astrocytes Suppresses Chronic Seizures in a Mouse Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Mol Neurobiol 2017; 54: 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goetzl EJ, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Kapogiannis D, Schwartz JB. Declining levels of functionally specialized synaptic proteins in plasma neuronal exosomes with progression of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J 2018; 32: 888–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Athauda D, Gulyani S, Karnati HK, Li Y, Tweedie D, Mustapic M, et al. Utility of Neuronal-Derived Exosomes to Examine Molecular Mechanisms That Affect Motor Function in Patients With Parkinson Disease: A Secondary Analysis of the Exenatide-PD Trial. JAMA Neurol 2019; 76: 420–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karnati HK, Garcia JH, Tweedie D, Becker RE, Kapogiannis D, Greig NH. Neuronal Enriched Extracellular Vesicle Proteins as Biomarkers for Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma 2019; 36: 975–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pulliam L, Sun B, Mustapic M, Chawla S, Kapogiannis D. Plasma neuronal exosomes serve as biomarkers of cognitive impairment in HIV infection and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurovirol 2019; doi: 10.1007/s13365-018-0695-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Madhu LN, Attaluri S, Kodali M, Shuai B, Upadhya R, Gitai D, Shetty AK. Neuroinflammation in Gulf War Illness is linked with HMGB1 and complement activation, which can be discerned from brain-derived extracellular vesicles in the blood. Brain Behav Immunity, in press. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Karttunen J, Heiskanen M, Lipponen A, Poulsen D, Pitkänen A. Extracellular Vesicles as Diagnostics and Therapeutics for Structural Epilepsies. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20, pii: E1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Batrakova EV, Kim MS. Using exosomes, naturally-equipped nanocarriers, for drug delivery. J Control Release 2015; 219: 396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vogel A, Upadhya R, Shetty AK. Neural stem cell derived extracellular vesicles: Attributes and prospects for treating neurodegenerative disorders. EBioMedicine 2018; 38: 273–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shetty AK, Upadhya R, Attaluri S, Pinson M, Xu J, Shuai B. Intranasal administration of exosomes from human iPSC-derived MSCs enhances neural stem/progenitor cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the normal adult hippocampus. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts, 2018; 636.16. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Castro OW, Kodali M, Upadhya R, Kim D-K, Shuai B, Prockop DJ, et al. Distribution of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in the intact and injured brain following intranasal administration. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts, 2017; 740.15. [Google Scholar]