Abstract

Background:

Premature birth is associated with high prevalence of neurodevelopmental impairments in surviving infants. The putative role of cerebellar and brainstem dysfunction remains poorly understood, particularly in the absence of overt structural injury.

Method:

We compared in-utero versus ex-utero global, regional and local cerebellar and brainstem development in healthy fetuses (n=38) and prematurely born infants without evidence of structural brain injury on conventional MRI studies (n=74) that were performed at two time points: the first corresponding to the third trimester, either in utero or ex utero in the early postnatal period following preterm birth (30–40 weeks of gestation; 38 control fetuses; 52 premature infants) and the second at term equivalent age (37–46 weeks; 38 control infants; 58 premature infants). We compared 1) volumetric growth of 7 regions in the cerebellum (left and right hemispheres, left and right dentate nuclei, and the anterior, neo, and posterior vermis); 2) volumetric growth of 3 brainstem regions (midbrain, pons, and medulla); and 3) shape development in the cerebellum and brainstem using spherical harmonic description between the two groups.

Results:

Both premature and control groups showed regional cerebellar differences in growth rates, with the left and right cerebellar hemispheres showing faster growth compared to the vermis. In the brainstem, the pons grew faster than the midbrain and medulla in both prematurely born infants and controls. Using shape analyses, premature infants had smaller left and right cerebellar hemispheres but larger regional vermis and paravermis compared to in-utero control fetuses. For the brainstem, premature infants showed impaired growth of the superior surface of the midbrain, anterior surface of the pons, and inferior aspects of the medulla compared to the control fetuses. At term-equivalent age, premature infants had smaller cerebellar hemispheres bilaterally, extending to the superior aspect of the left cerebellar hemisphere, and larger anterior vermis and posteroinferior cerebellar lobes than healthy newborns. For the brainstem, large differences between premature infants and healthy newborns were found in the anterior surface of the pons.

Conclusion:

This study analyzed both volumetric growth and shape development of the cerebellum and brainstem in premature infants compared to healthy fetuses using longitudinal MRI measurements. The findings in the present study suggested that preterm birth may alter global, regional and local development of the cerebellum and brainstem even in the absence of structural brain injury evident on conventional MRI.

Keywords: Premature infant, full term infant, healthy fetus, cerebellum, brainstem

1. Introduction

Structural brain injury in infants born prematurely has significantly declined, yet the prevalence of neurodevelopmental dysfunction in the years following preterm birth remains alarmingly high (Blencowe et al., 2013; Jarjour, 2015; Milner et al., 2015; Stensvold et al., 2017). Impaired cerebellar development has been recently implicated in this dysfunction (Brossard-Racine et al., 2015; Limperopoulos et al., 2007). We and others have described a previously under-recognized form of prematurity-related cerebellar parenchymal injury in up to 20% in extremely premature infants (Limperopoulos et al., 2005a; Steggerda et al., 2009). Cerebellar parenchymal injury is followed by significant regional growth impairment of remote neocortical circuits, suggesting an interruption of cerebello-cerebral connectivity and loss of neuronal activation critical for development (Limperopoulos et al., 2012). Such injury is associated with a distinct phenotype of cognitive, affective, and behavioral dysfunction, known as the developmental cerebellar cognitive affective disorder (Brossard-Racine et al., 2015; Limperopoulos et al., 2007). This spectrum of neurodevelopmental impairment is not surprising given that different cerebellar subregions support motor and non-motor processes (Stoodley, 2014; Stoodley and Limperopoulos, 2016).

Cerebellar developmental impairment in the absence of direct cerebellar parenchymal injury has also been described and related to such factors as prematurity-related brain injury, to medical complications associated with prematurity itself, or to a combination of these factors (Bouyssi-Kobar et al., 2016; Brossard-Racine et al., 2015, 2017b, 2018; Limperopoulos et al., 2005a, 2007). Cerebellar development has been shown to be markedly accelerated during the third trimester, but significantly impeded after premature birth, even in the absence of direct cerebellar injury (Brossard-Racine et al., 2018; Limperopoulos et al., 2005b; Volpe, 2009). Central to this critical period of development are remarkably complex, rapid and precisely programmed events in the cerebellum, rendering it vulnerable to a host of potential insults to which the very premature infant is exposed.

The cerebellum maintains functionally segregated, reciprocal connections with almost all areas in the neocortex. For example, the neocerebellum (i.e, the cerebellar hemispheres except for the floccule (Altman et al., 1992)) has principally corticopontocerebellar connections (Sato et al., 2015). The brainstem plays a critical role in relaying information between the cerebrum and cerebellum and impaired brainstem development has also been implicated in preterm birth and outcome (Jiang and Li, 2015; Valkama et al., 2001). Disturbed brainstem development in premature infants has been implicated in central respiratory disorders, including apnea of prematurity and infancy, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome, and sudden infant death syndrome (Brazy et al., 1987; Darnall et al., 2006; Kinney, 2006; Nino et al., 2016). Brainstem dysfunction after preterm birth has also been implicated in behavioral inhibition (Geva et al., 2014). Other evidence suggesting that brainstem development in premature infants is less mature than full-term infants, includes impaired brainstem auditory function (Jiang and Ping, 2016; Jiang and Wang, 2016; Stipdonk et al., 2016) and impaired neural control of respiration (Darnall et al., 2006; Stojanovska et al., 2018).

Volumetric MRI methods have been widely used to analyze the cerebellar and brainstem growth in premature infants (Alexander et al., 2019; Bouyssi-Kobar et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016; Limperopoulos et al., 2005b, 2005c; Volpe, 2009; Zwicker et al., 2016), and recent technological advances in fetal MRI provided an unprecedented opportunity to study brain development in premature infants in the early postnatal period compared to in utero healthy fetuses (Bouyssi-Kobar et al., 2016; Brossard-Racine et al., 2018). Recently, local shape changes in the cerebellum and brainstem in premature infants with vs without brain injury have been described (Kim et al., 2016), where premature infants with severer intraventricular hemorrhage showed slower growth on the posterior superior cerebellar lobe and pons, and infants with severe cerebellar hemorrhage showed slower growth on the posterior inferior lobe, posterior vermis, and tonsil compared to infants with no or mild imaging evidence of injury (Kim et al., 2016). However, to our knowledge, no study has elucidated the onset and progression of local shape differences in the cerebellum and brainstem in prematurely born infants versus in utero healthy fetuses.

In the current study, we used advanced volumetric MRI to compare cerebellar and brainstem development in ex-utero premature infants with healthy in-utero fetuses over the third trimester (MRI-1) and at term-equivalent age (MRI-2). We aimed to quantify 1) shape development of the cerebellum and the brainstem using spherical harmonic description (SPHARM) (Brechbühler et al., 1995); 2) volumetric growth in 7 regions of the cerebellum [left hemisphere (LH), right hemisphere (RH), anterior vermis (AV), neo vermis (NV), posterior vermis (PV), left dentate nucleus (LDN), and right dentate nucleus (RDN)]; and 3) volumetric growth in 3 regions of the brainstem (midbrain, pons, and medulla).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

As part of a prospective study, we enrolled 74 premature infants born ≤32 weeks and ≤1500 g birth weight who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of the Children’s National Health System. Thirty-six of the 74 premature infants had scans at both preterm period and term equivalent ages (TEA) and 38 premature infants had one MRI scan. There was a total of 110 MRI scans in the premature group (range: 30.6–44.4 gestational weeks). Thirty-eight controls were recruited from healthy pregnant volunteers with normal fetal ultrasounds and biometry studies from a parallel study. All controls underwent MRI studies in both the fetal period (38 MRI scans; range: 30.3–39.4 gestational weeks) and neonatal period (38 MRI scans; range: 38.4–46.4 gestational weeks) (Table 1). Our exclusion criteria were: 1) fetuses or infants with known or suspected genetic or chromosomal abnormalities, metabolic disorder, congenital infection, multiorgan dysmorphic conditions, and/or brain MRI abnormalities; 2) pregnant women with known metabolic or genetic disorders, multiple pregnancy, and/or contraindications for MRI (e.g., claustrophobia, mechanical heart valve, pacemaker, or other metal implants). Written informed parental consent was obtained for each subject following a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Children’s National Health System before enrollment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cohort.

| Mean±SD (Min-Max) or N (%) | Premature Infants (N = 74) | Controls (N = 38) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 31 (42%) | 20 (53%) | 0.32 |

| GA at MRI 1 (weeks) | 34.1±2.1 (30.6–39.7) | 34.5±1.9 (30.3–39.4) | 0.39 |

| GA at MRI 2 (weeks) | 40.2±1.6 (37.3–44.4) | 41.4±1.6 (38.4–46.4) | 0.0005 |

| GA at birth (weeks) | 27.6±2.5 (22–32) | 39.4±0.9 (37.3–41.3) | <.0001 |

| Weight at MRI-1 (grams) | 1670.4±405.7 (770–2660) | -- | -- |

| Weight at MRI-2 (grams) | 2933.9±762.3 (1760–5440) | 3590.9±472.3 (2667–4470) | <.0001 |

| Weight at birth (grams) | 949±288.6 (400–1485) | 3315.6±330.5 (2594–3968) | <.0001 |

| Head circumference at MRI-1 (cm) | 28.5±2.7 (20.5–35.5) | -- | -- |

| Head circumference at MRI-2 (cm) | 33.4±1.9 (28.5–37) | 35.73±1.50 (32–39) | <.0001 |

| Apgar score 1 min (median, IQR) | 5 (4) | 9 (1) | <.0001 |

| Apgar score 5 min (median, IQR) | 8 (2) | 9 (0) | <.0001 |

| Delivery Method | <.0001 | ||

| Intubation at birth | 56 (76%) | 0 (0) | <.0001 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus ligation | 14 (19%) | -- | -- |

| Neonatal infection | 33 (45%) | -- | -- |

| Chronic lung disease | 27 (36%) | -- | -- |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 21 (28%) | -- | -- |

| Surgery for necrotizing enterocolitis | 6 (8%) | -- | -- |

| Days on supplementary oxygen | 58.5±42.5 (2–172) | -- | -- |

| Days in NICU | 81.3±36.3 (26–206) | -- | -- |

| Number of antibiotics types in NICU, median [range] | 3 [0–8] | -- | -- |

| Opioid exposures in NICU | -- | -- | |

| Steroid exposures in NICU | -- | -- |

P value for difference between full term and preterm groups based on t-test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

2.2. MRI acquisition

Premature infants requiring temperature monitoring (N=30) underwent scanning with a MRI compatible incubator (LMT Medical Systems GmbH, Luebeck, Germany) using a 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner (GE Discovery MR450) with a 1-channel transmit-receive head coil. The MRI scanning protocol included sagittal, coronal and axial single shot fast spin echo acquisitions (repetition time: 1100 ms; echo time: 160 ms; flip angle: 90°; field-of-view: 12 cm; matrix: 192×128; in-plane resolution: 0.625×0.94 mm2; 2-mm slice thickness). Premature infants who did not need the incubator for temperature monitoring during the MRI and for transport and healthy neonates were scanned on a 3 Tesla MRI scanner (GE Discovery MR750) with an 8-channel HiRes brain array receive only coil (T2-weighted 3D CUBE sequence; repetition time: 2500 ms; echo time: 64.7 ms; flip angle: 90°; 0.625×0.625×1 mm3). Fetal scans were acquired in the axial, coronal and sagittal planes using a 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner (GE Discovery MR450) and an 8-channel cardiac array receive only coil (single shot fast spin echo; repetition time: 1100 ms; echo time: 160 ms; flip angle: 90°; field-of-view: 32 cm; matrix: 256×192; in-plane resolution: 1.25×1.66 mm2; 2-mm slice thickness), and the mothers were free breathing during the scanning.

2.3. Image preprocessing

For preterm and fetal MRI scans using single shot fast spin echo acquisition, the images from all three planes (sagittal, coronal and axial) were reconstructed into a single high resolution 3D volume based on a slice-to-volume reconstruction method employing evaluated point-spread functions to reconstruct the images from motion-corrupted stacks of 2D slices (Kainz et al., 2015). After image reconstruction, all images were spatially aligned using landmark-based rigid registration to the preterm brain atlas (28–44 weeks) created by Imperial College London (Serag et al., 2012). The aligned high resolution 3D images (0.86×0.86×0.86 mm3) were utilized for segmentation. All MRI studies were reviewed by experienced neuroradiologists (G.V. and J.M.). Subjects with evidence of structural brain injury or severe motion artifact on conventional MRI were subsequently excluded from this study.

2.4. Image segmentation

Manual segmentation of the cerebellum and brainstem was performed on T2-weighted MRI scans using ITK-SNAP software. The cerebellum was manually segmented into 7 regions: left and right hemispheres, left and right dentate nuclei, and the anterior, neo and posterior vermis based on previously reported anatomical criteria (Bogovic et al., 2013; Rutherford and Bydder, 2002; Yucel et al., 2013). Specifically, the vermal region was extracted using the sagittal plane based on its intensity differences with the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid which is with high intensities in T2-weighted MR images (Figure 1). The anterior and neo vermal regions were separated by the primary fissure, and the neo and posterior vermal regions were separated by the prepyramidal fissure (Bogovic et al., 2013; Yucel et al., 2013). After segmenting the vermis, the cerebellum was separated into left and right. The left and right cerebellar hemispheres were further separated from the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid (Figure 1). We used the axial plane to segment cerebellar hemispheres first and then corrected using the sagittal plane with concurrent review of the coronal plane. The dentate nuclei were segmented based on its intensity difference with nearby cerebellar tissues (Rutherford and Bydder, 2002) using the sagittal plane first and then corrected using the coronal plane with concurrent review of the axial plane. The brainstem was segmented into pons, midbrain, and medulla based on anatomical features described in MRI brainstem segmentation protocol (Iglesias et al., 2015; Young, 2011). Total brain volume (TBV) was obtained using the DrawEM segmentation pipeline (Makropoulos et al., 2014), and then manually corrected. An experienced neuroradiologist (G.V.) assisted with the anatomical segmentation of these brain regions in MRI images. All segmentations were performed by the same trained rater (i.e., rater1). The segmentation process was consistent in all our dataset. Twenty percent of the total scans (22 preterm scans, 15 control scans) were randomly selected and segmented by rater1 and a second trained rater (i.e., rater2). Intra- and inter-rater reliabilities using intraclass correlation coefficient for all measured regions were higher than 0.91, indicating good agreement between the segmentations from the same and different raters. Raters were blinded to all clinical information during image segmentation.

Figure 1.

Manual segmentation of the regional cerebellum and brainstem of a premature infant (1st row) and healthy fetus (2nd row) at 34 gestational weeks (acquired on 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner; red=left cerebellar hemisphere, blue=right cerebellar hemisphere, green=anterior vermis, cyan=neo vermis, yellow=posterior vermis, purple=left dentate nucleus, orange=right dentate nucleus, brown=midbrain, light brown=pons, pink=medulla].

Figure 1 shows the manual segmentation of the regional cerebellum and brainstem of a premature infant (1st row) and healthy fetus (2nd row) at 34 gestational weeks.

2.5. Shape analysis using SPHARM

Spherical harmonic description (SPHARM) which uses spherical harmonics to construct parametric surface models was used to measure shape differences between compared groups (Brechbühler et al., 1995; Gerig et al., 2001; Styner et al., 2006). The following steps are usually required using SPHARM (Shen et al., 2010): 1) spherical parameterization, which maps the object surface to a unit sphere surface; 2) SPHARM expansion, which expands the object surface into spherical harmonic representation; 3) surface alignment, which aligns all surface models together for the following group analysis; 4) statistical analysis, which statistically analyzes shape changes between groups of objects. In our analysis, the surface of the object (i.e., cerebellum or brainstem) was mapped onto a sphere based on area-preserving and distortion-minimizing mapping (i.e., spherical parameterization). Correspondences (2,562 vertices) across object surfaces were obtained using a uniform icosahedron-subdivision (Gerig et al., 2001; Kelemen et al., 1999) (i.e., SPHARM expansion). An average surface was constructed by iteratively registering the object surfaces of compared groups and was used as the atlas (Shen et al., 2009). Thereafter, all individual surfaces were rigidly aligned to the atlas (i.e., surface alignment). Surface-based vertex-wise distances were calculated between each individual and the atlas and were further statistically analyzed between compared groups (i.e., statistical analysis).

Here we present two types of surface differences: 1) surface differences without scaling the object size but controlling for gestational age (GA) at MRI; 2) differences after scaling the object size inversely to the TBV of each subject (i.e., scaled object size = original object size * 1/TBV). The first analysis (i.e., non-scaling) represents a raw analysis, whereas the TBV scaling analysis normalizes for brain size differences and thus controls for the effect of any overall brain size changes (Styner et al., 2006).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB and SAS software. Subject characteristics and birth measures between groups were compared using t-test or Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Generalized linear models were used to compare the measured brain volumes (7 regions in the cerebellum [left and right hemispheres, left and right dentate nuclei, and the anterior, neo, and posterior vermis] and 3 brainstem regions [midbrain, pons, and medulla]) and shape analysis in premature infants versus healthy controls at fetal or term period, controlling for GA at MRI. The same models were then repeated for the volumetric comparison, additionally controlling for TBV. In the shape analysis scaled by TBV, t-test was used to compare the shape differences in premature infants versus healthy controls at MRI-1 or MRI-2. Generalized estimating equations allowing for multiple measurements per subject were used to estimate the volumetric growth and shape development across GA in the premature and control groups. In both volumetric and shape analyses, the false discovery rate was used to adjust p values for multiple testing according to the Benjamini-Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995), and adjusted p values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

In our dataset, premature infants and healthy fetuses had similar GAs at MRI-1 (30–40 weeks); GAs at MRI-2 for both premature and control infants were >37 weeks. For the 38 premature infants with only one MRI scan, the scans with GA <37 weeks (N=16) were grouped as MRI-1, and the scans with GA≥37 weeks (N=22) were grouped as MRI-2. Detailed clinical and demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

3.2. Volumetric growth of the cerebellum

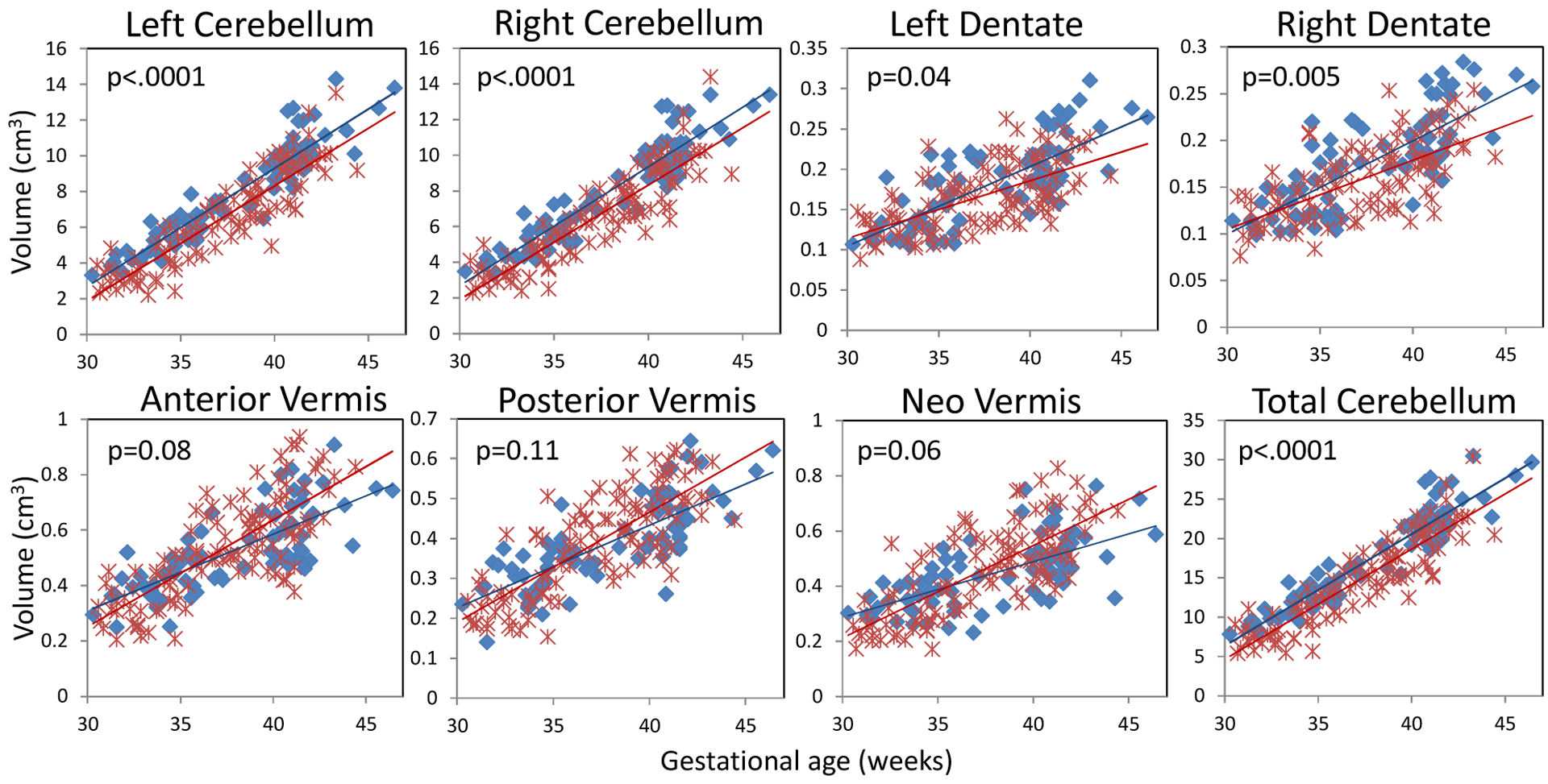

Volumes of seven regions of the cerebellum and total cerebellum in premature infants and controls are shown in Figure 2. Each point denotes the cerebellar volume of one subject. Solid line denotes linear growth curve for volumes in one group. Overall, volumes of the left and right cerebellar hemispheres and dentate nuclei in premature infants were smaller compared to controls (Figure 2). The anterior, neo-, and posterior vermis in premature infants were larger than normal controls after 36 weeks GA. The growth rates (cm3/week) in each region of the cerebellum from 30 to 46 weeks are shown in Table 2. All 7 regions of the cerebellum increased in volume at different rates. The left and right cerebellar hemisphere volumes increased faster than the vermis and dentate nuclei volumes in both premature and control groups. The growth rates of the left and right cerebellar hemispheres and dentate nuclei in premature infants were slower than those in controls. In contrast, the growth rates of vermis regions in premature infants were faster compared to controls.

Figure 2.

Scatter plot and linear growth curves for 7 regions of the cerebellum and the total cerebellar volumes in controls (blue) and premature infants (red). (P value based on linear generalized estimating equations model, controlling for GA at MRI).

Table 2.

Cerebellar growth in premature infants and controls estimated from linear generalized estimating equations model. LH=left hemisphere, RH=right hemisphere, LDN=left dentate nucleus, RDN=right dentate nucleus, AV=anterior vermis, NV=neo vermis, PV=posterior vermis, and CBL=cerebellum.

| LH | RH | LDN | RDN | AV | PV | NV | Total CBL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls | ||||||||

| Model (y = at + b) | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.58 | 0.41 | 0.88 |

| Growth rate (a), cm3/week | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.42 |

| Constant (b), cm3 | −17.19 | −17.35 | −0.19 | −0.20 | −0.52 | −0.39 | −0.32 | −36.21 |

| Premature infants | ||||||||

| Model (y = at + b) | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 0.81 |

| Growth rate (a), cm3/week | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.40 |

| Constant (b), cm3 | −17.43 | −17.34 | −0.10 | −0.12 | −0.90 | −0.64 | −0.79 | −37.32 |

Cerebellar volume comparison of premature infants and healthy controls at MRI-1 (30–40 weeks) and MRI-2 (37–46 weeks) are shown in Table 3. At MRI-1, premature infants had smaller left and right cerebellar hemispheres and smaller total cerebellar volumes compared to in utero healthy fetuses. At MRI-2, premature infants continued to show smaller left and right cerebellar hemispheres and smaller dentate nuclei, but had larger anterior vermis and neo vermis than healthy controls. When additionally adjusting for TBV (Table 4), the hemispheric differences were no longer statistically significant; however, the anterior vermis and posterior vermis in premature infants remained larger than controls at MRI-2.

Table 3.

Regional and total cerebellar volumes in premature infants and controls at MRI-1 (top row) and MRI-2 (bottom row), adjusting for gestational age at MRI. LH= left hemisphere, RH=right hemisphere, LDN=left dentate nucleus, RDN=right dentate nucleus, AV=anterior vermis, NV= neo vermis, PV=posterior vermis, and CBL=cerebellum.

| LH | RH | LDN | RDN | AV | NV | PV | Total CBL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | ||

| MRI-1 | Control Fetuses (38 scans) | 5.43 | <.0001* | 5.43 | <.0001* | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.71 | 12.27 | <.0001* |

| MRI-2 | Control Infants (38 scans) | 9.83 | 0.0005 * |

9.92 | 0.0001 * |

0.21 | 0.04* | 0.20 | 0.01* | 0.60 | 0.03* | 0.50 | 0.005* | 0.45 | 0.06 | 21.72 | 0.0008 * |

Results of least squares means estimates from generalized linear model, controlling for gestational age at MRI.

MRI-1 denotes the timepoint of the third trimester (either in utero or ex utero in the early postnatal period following preterm birth);

MRI-2 denotes the timepoint of term equivalent age;

Significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

Table 4.

Comparison of regional and total cerebellar volumes in premature infants and controls at MRI-1 and MRI-2, adjusting for gestational age at MRI and total brain volume.

| LH | RH | LDN | RDN | AV | NV | PV | Total CBL | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | ||

| MRI-1 | Control Fetuses (38 scans) | 5.08 | 0.09 | 5.08 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.63 | 0.14 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 11.50 | 0.17 |

| MRI-2 | Control Infants (38 scans) | 9.08 | 0.34 | 9.18 | 0.65 | 0.20 | 0.99 | 0.19 | 0.91 | 0.58 | 0.01* | 0.50 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.008* | 20.18 | 0.29 |

Results of least squares means estimates from generalized linear model, controlling for gestational age at MRI and total brain volume.

MRI-1 denotes the timepoint of the third trimester (either in utero or ex utero in the early postnatal period following preterm birth);

MRI-2 denotes the timepoint of term equivalent age;

Significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

3.3. Volumetric growth of the brainstem

Volumes of the midbrain, pons, medulla and total brainstem in premature infants and controls are shown in Figure 3. All 3 regions of the brainstem in premature infants were smaller compared to healthy controls at both MRI-1 and MRI-2. The growth rates of the total brainstem were similar in premature infants and controls; however, the midbrain of premature infants grew faster than that of controls, while the pons and medulla in premature infants grew slower than controls (Table 5). In both premature infants and controls, the midbrain, pons, and medulla grew at different rates, where the pons grew faster than the midbrain and medulla (Table 5).

Figure 3.

Scatter plot and linear growth curves for volumes of midbrain, pons, medulla, and total brainstem in controls (blue) and premature infants (red). (P values based on linear generalized estimating equations model, controlling for GA at MRI)

Table 5.

Brainstem growth in premature infants and controls estimated from linear generalized estimating equations model.

| Midbrain | Pons | Medulla | Total Brainstem | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls | ||||

| Model (y = at + b) | ||||

| R2 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.82 |

| Growth rate (a), cm3/week | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.23 |

| Constant (b), cm3 | −0.15 | −1.91 | −1.25 | −3.32 |

| Premature infants | ||||

| Model (y = at + b) | ||||

| R2 | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.70 |

| Growth rate (a), cm3/week | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.23 |

| Constant (b), cm3 | −1.01 | −1.98 | −0.80 | −3.80 |

The comparison of brainstem volumes in premature infants and healthy controls at MRI-1 and MRI-2 are shown in Table 6. All three brainstem regions were smaller in premature infants compared to controls at both time points. When additionally adjusting for TBV (Table 7), the medulla remained smaller in premature versus control infants at MRI-2 (p=0.005).

Table 6.

Regional and global brainstem volumes in premature infants and controls at MRI-1 and MRI-2, controlling for GA at MRI.

| Midbrain | Pons | Medulla | Total Brainstem | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | P | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | ||

| MRI-1 | Control Fetuses (38 scans) | 1.90 | <.0001* | 1.74 | <.0001* | 1.0 | 0.004* | 4.63 | <.0001* |

| MRI-2 | Control Infants (38 scans) | 2.33 | 0.0003* | 2.49 | <.0001* | 1.47 | <.0001* | 6.28 | <.0001* |

Results of least squares means estimates from generalized linear model, controlling for gestational age at MRI.

MRI-1 denotes the timepoint of the third trimester (either in utero or ex utero in the early postnatal period following preterm birth);

MRI-2 denotes the timepoint of term equivalent age;

Significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

Table 7.

Regional and global brainstem volumes in premature infants and controls at MRI-1 and MRI-2, controlling for GA at MRI and total brain volume.

| Midbrain | Pons | Medulla | T otal Brainstem | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | Mean | p | ||

| MRI-1 | Control Fetuses (38 scans) | 1.81 | 0.05 | 1.65 | 0.20 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 4.42 | 0.11 |

| MRI-2 | Control Infants (38 scans) | 2.21 | 0.34 | 2.37 | 0.18 | 1.39 | 0.005* | 5.96 | 0.14 |

Results of least squares means estimates from generalized linear model, controlling for gestational age at MRI and total brain volume.

MRI-1 denotes the timepoint of the third trimester (either in utero or ex utero in the early postnatal period following preterm birth);

MRI-2 denotes the timepoint of term equivalent age;

Significant after adjusting for multiple testing.

3.4. Shape development of the cerebellum and brainstem

Images depicting shape development of the cerebellum and brainstem in premature infants and healthy controls are shown in Figure 4. The atlas for each of the preterm and control groups was created from all participants in that group. Different colors overlaid on the atlas indicate different growth rates, where red regions represent higher growth rates and blue regions indicate lower growth rates. The lateral cerebellar hemispheres showed more rapid expansion than midline cerebellar regions in both premature infants and controls. For the brainstem, the superior aspect of the midbrain, anterior aspect of the pons, and inferior aspect of the medulla grew faster than other regions in both premature infants and controls.

Figure 4.

Shape development of the cerebellum (1–2 rows) and brainstem (3–4 rows) in premature and control infants. The image in each row is an atlas representing the average shape in that group (premature or control). Red regions represent higher growth rates and blue regions indicate lower growth rates.

3.5. Cerebellar and brainstem shape differences in premature infants vs controls

Figure 5 shows four views (i.e., anterior, posterior, superior, and inferior) of the atlas, with t-maps overlaid showing the comparison between the two groups. The atlas for MRI-1 and MRI-2 was created from all participants of the compared groups at each time point, respectively. When controlling for GA at MRI, premature infants had significantly smaller (blue) left and right cerebellar hemispheres and larger (red) regional vermis and paravermis than control fetuses at MRI-1 (1st row in Figure 5). Regions with no color indicate no significant surface differences between the two groups. At MRI-2 (2nd row in Figure 5), premature infants had significantly smaller bilateral cerebellar hemispheres, extending to the superior aspect of the left cerebellar hemisphere, and larger anterior vermis and posteroinferior cerebellar lobes than control infants. For the brainstem, at MRI-1 premature infants had a significantly smaller superior surface of the midbrain, anterior surface of the pons, and inferior aspects of the medulla compared to control fetuses (3rd row in Figure 5). At MRI-2, a large difference between premature and control infants was evident on the anterior surface of pons (4th row in Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cerebellum and brainstem shape differences in premature infants and healthy controls. The 1st and 3rd rows represent the cerebellum and brainstem differences between premature infants versus control fetuses (MRI-1). The 2nd and 4th rows represent the cerebellum and brainstem differences between premature vs control infants at TEA (MRI-2). Blue regions were smaller and red regions were larger in premature infants versus controls. The significant regions were created by thresholding the t-map using ±2.2, ±2.4, −2.5, and −2.6 for rows 1–4, respectively, which correspond to an adjusted p value of 0.05.

3.6. Shape analysis scaling by total brain volume

When scaling the cerebellum and brainstem sizes by TBV, at MRI-1 premature infants still had smaller (blue) left and right cerebellar hemispheres relative to control fetuses (1st row in Figure 6). At MRI-2, premature infants had altered bilateral hemispheres, extending to the medial cerebellum compared to control infants (2nd row in Figure 6). There were no shape differences in the brainstem between premature infants and controls when scaling by TBV.

Figure 6.

Cerebellar shape differences in premature infants and healthy controls scaled by total brain volume. The 1st row represents the differences between premature infants versus control fetuses (MRI-1). The 2nd row represents the differences between premature vs control infants at TEA (MRI-2). Blue regions were smaller and red regions were larger in premature infants versus controls. The significant regions were created by thresholding the t-map using −2.3 and ±2.7 for rows 1 and 2, respectively, which correspond to an adjusted p value of 0.05.

4. Discussion

This study examined both volumetric growth and local shape differences of the cerebellum and brainstem in ex-utero premature infants compared to in-utero healthy fetuses using longitudinal MRI measurements. At MRI-1, we demonstrated that premature infants had smaller cerebellar hemispheres and larger regional vermis and paravermis compared with healthy in-utero fetuses (Figure 5). We also demonstrated local brainstem differences in premature infants compared to healthy fetuses, including the superior surface of the midbrain, anterior surface of the pons, and inferior aspects of the medulla (Figure 5). These data suggest that even in the absence of structural brain injury on conventional MRI, the development of the cerebellum and brainstem during the third trimester may be altered following early extrauterine exposure, and alterations in the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres, superior aspect of the left cerebellar hemisphere, posteroinferior cerebellar lobes, anterior vermis, and the anterior aspect of the pons persisted at TEA (Figure 5).

Compared with healthy controls, premature infants had smaller bilateral cerebellar hemispheres during both third trimester preterm and term-equivalent periods (Figure 5). Atypical growth of the lateral cerebellar hemispheres has been associated with impaired cognitive function, with decreased volume of the lateral hemispheres associated with neuropsychological dysfunction in adolescents born very preterm (Allin et al., 2005). At TEA, our premature subjects had smaller superior aspect of the left cerebellar hemisphere, and larger posteroinferior cerebellar regions than healthy newborns (Figure 5). These alterations remained after removing the influence of size differences in total brain volume (Figure 6). The altered lateral cerebellar hemispheres and posteroinferior cerebellar regions can be considered part of the “cognitive cerebellum” (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2010), including cerebellar regions involved in cognitive, language, and executive functions (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2010, 2009). The growth rates of the dentate nuclei were slower in premature infants than healthy controls. The cognitive cerebellar regions project via the dentate nuclei, and injury to the dentate nuclei is important for cognitive deficits in patients following cerebellar lesions (Ilg et al., 2013; Stoodley et al., 2016; Tedesco et al., 2011). Our results indicate that preterm birth may interrupt the growth of cognitive regions of the cerebellum more than motor regions (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2010, 2009). Whether cognitive function in premature infants is more impaired than motor control requires long-term follow-up of our preterm cohort which is currently underway.

Both our volumetric and shape results demonstrate that vermal regions showed slower growth than the cerebellar hemispheres in both premature and control infants (Table 2 and Figure 4), which is consistent with a previous preterm hindbrain study showing faster growths in the lateral convexity of cerebellar lobes and pons than other hindbrain regions in premature infants without imaging evidence of injury (Kim et al., 2016). We also report larger regional vermis in premature infants compared to controls from both volumetric and shape analysis (Tables 3 and 4, and Figures 2 and 5). This is consistent with previous ultrasound studies that reported a larger cerebellar vermis in premature infants at TEA compared to term infants (Graça et al., 2013; Sancak et al., 2016) and our previous MRI study which suggested that premature infants had larger vermal volumes than age-matched healthy controls (Brossard-Racine et al., 2018) as well as a recent study showing larger anterior cerebellar vermis volumes at TEA in infants born more preterm (Alexander et al., 2019). Conversely, Alexander et al. (Alexander et al., 2019) found smaller inferior posterior cerebellar vermis volumes in infants born at earlier GA. Further studies are needed to confirm our initial observations. A larger vermis has been associated with poorer executive functioning (Medina et al., 2010), and increased vermis white-matter volume has been associated with poor verbal fluency performance in patients with schizophrenia (Lee et al., 2007). Furthermore, lesions in vermal regions are often associated with neurodevelopmental disorders including behavioral dysregulation, emotional problems, and an autism-like phenotype (Becker and Stoodley, 2013; Hampson and Blatt, 2015; Hernaez-Goni et al., 2010; Schmahmann et al., 2007; Stoodley, 2014; Stoodley and Limperopoulos, 2016). These alterations in cerebellar vermis development in prematurely born infants may underlie the behavioral and emotional problems described in children and adults born prematurely.

Using anatomical longitudinal data, we found that the premature infants demonstrate impaired brainstem growth relative to healthy controls over the third trimester and at term-equivalent age (Table 6 and Figures 3 and 5). Consistently, a recent study (Alexander et al., 2019) suggested smaller brainstem volumes at TEA in infants born more preterm. In our current study, premature infants prior to TEA showed atypical structure of the superior surface of the midbrain, anterior surface of the pons, and right inferior aspect of the medulla compared to healthy fetuses (Figure 5). These altered regions in the brainstem involved in the motor learning and function (Schmahmann et al., 2004; Schweighofer et al., 2013). At TEA, differences in development persisted in the anterior surface of the pons and inferior posterior medulla compared to healthy neonates (Figure 5). The dorsomedial region of the medulla is comprised of the solitary tract nucleus (STN), which propagates peripheral chemosensory information to major respiratory centers within the brainstem to evoke respiratory responses (Stojanovska et al., 2018). The altered regions of the brainstem might partially explain the motor deficits and impaired neural control of respiration in premature infants. However, whether unilateral (in our case right inferior) impairment of STN development might predispose to the impaired autonomic function described in survivors of prematurity (Haraldsdottir et al., 2018; Mathewson et al., 2015; Mulkey et al., 2018; Nino et al., 2016) is unclear. Further follow-up studies are currently underway to ascertain the influence of differential growth in brainstem regions on long-term functional outcomes in premature infants.

The mechanisms underlying altered ex-utero cerebellar and brainstem growth are complex. It is known that intrauterine inflammatory pathways play a role in the causal pathways to preterm birth, and inflammation (with elevated prostaglandin synthesis) has been implicated in functional changes in brainstem neurons (Stojanovska et al., 2018). Our previous studies showed reduced mean diffusivity in the cerebellar vermis (Brossard-Racine et al., 2017b) and increased cerebellar choline (Brossard-Racine et al., 2017a) in premature infants at TEA compared to controls. These microstructural and biochemical disturbances could be a consequence of altered cerebellar programming. During late stages of gestation, there are dramatic maturational changes in the brain mediated by neuronal differentiation, neurotransmitter receptors, synaptogenesis, and myelination, among other processes (Darnall et al., 2006). The third trimester has been shown to be a critical period for dynamic brain growth, especially for the cerebellum (Andescavage et al., 2016; Matthews et al., 2018). Early exposure to the extra-uterine environment may delay the rate of myelination (Stipdonk et al., 2016), which may in turn contribute to impaired cerebellar development. Additionally, certain clinical factors and exposures have been associated with altered cerebellar development including birthweight, duration of intubation, postnatal infection, hypotension, procedural pain, and cumulative steroid and opioid exposures in the NICU (Brossard-Racine et al., 2018; Grunau et al., 2009; McPherson et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2011; Tam et al., 2011; Zwicker et al., 2016). Low birthweight (<1500 g) and receiving mechanical ventilation and ≥5 different antibiotics in the NICU have shown associations with impaired auditory brainstem dysfunction in premature infants (Gupta et al., 1991; Suzuki and Suzumura, 2004). Moreover, a neuropathological study of premature infants (Pierson et al., 2007) showed that gliosis in inferior olive and basis pontis was observed in 92–100% of infants with periventricular leukomalacia that are often invisible by most conventional MRI (Back, 2017; Pierson et al., 2007; Volpe, 2019) and in 79–92% of infants with diffuse white matter gliosis without focal necrosis. Diffuse white matter gliosis was also noted in the cerebellum in 85% of premature infants, and this percentage increased throughout the premature period (Pierson et al., 2007). These findings raise the question of whether the brainstem and cerebellar growth impairments in premature infants reported in this study reflect, in part, primary injury or secondary dysmaturational effects of the white matter impairments that are below the resolution of conventional MRI studies. Furthermore, studies suggested altered granule cells and Bergmann glia as well as reduced expression of sonic hedgehog in the Purkinje layer in the cerebellum following preterm birth (Haldipur et al., 2011; Iskusnykh et al., 2018). Opioid and infection, which over half of our premature infants had been exposed to (Table 1), may cause apoptosis of Purkinje cells that further impairs the proliferation of granule cells (Biran et al., 2012; Golalipour and Ghafari, 2012; Hutton et al., 2014; Ranger et al., 2015; Volpe, 2009). These studies provide another explanation of the disrupted cerebellar development in premature infants. Our findings also suggested that the shape differences in the pons in premature infants vs healthy fetuses persisted at TEA (Figure 5). Interestingly, there were fewer differences in the midbrain and lateral cerebellar hemispheres between premature infants and controls at MRI-2 compared to MRI-1. We postulate that the growth of these regions in premature infants may be accelerated as shown in Figure 4 and also suggested by Kim et al. (Kim et al., 2016) and may demonstrate catch-up growth by TEA. Conversely, the medial regions of the cerebellum (i.e., anterior vermis and posteroinferior cerebellar lobes) were larger in premature infants compared to control infants at TEA (Figure 5), which may by adaptive or maladaptive impacts reflect selective vulnerability and decreased apoptosis (Courchesne, 2004; Kuan et al., 2000; Kyriakopoulou et al., 2013) of these regions of the cerebellum following preterm birth. Functional activation of remote but targeted regions of the brain plays a critical role in structural development and consolidation of connectivity between brain regions (Limperopoulos et al., 2012, 2010). Although different cerebellar regions mediate different functions in the mature brain (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009), little is known about the functional topography of the immature cerebellum and brainstem (Stoodley and Limperopoulos, 2016). Ongoing studies are needed to better elucidate the impact of these regional alterations in cerebellar and brainstem development on long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

There are several limitations of the current study that should be noted. First, since in the shape analysis the statistical modeling was performed for each vertex of the atlas surface, the selection of the atlas could potentially introduce a bias. Nevertheless, studies have shown stable shape analysis results using this approach (Cong et al., 2014; Styner et al., 2006), and previous studies also used the averaged surface as the atlas in their analyses (Kim et al., 2016; Scott et al., 2012). Second, premature infants had smaller mean GA at MRI-2 compared to healthy infants (Table 1). In both volumetric and shape analysis, we controlled for GA at MRI scan to account for the GA difference between groups. Third, manual parcellation of the cerebellum and brainstem was used in this study, which could introduce inter-rater variability. Considering the specific regions measured in this study and large anatomical variances in the fetal/neonatal brain, we used manual parcellation to ensure accuracy in this study. For studies with large cohorts, automatic parcellation methods for the neonatal brain (Alexander et al., 2019; Blesa et al., 2016; Gousias et al., 2013; Makropoulos et al., 2016, 2014) could provide more efficient and objective results.

Another limitation of this work was that our premature infants were scanned on different scanners (1.5T and 3T), given that a subset of premature infants required the MRI compatible incubator to ensure temperature monitoring and maintenance. To reduce the influence of field strengths on the tissue contrast and the following analysis, MRI acquisition parameters were optimized empirically for both scanners. The image resolutions from 1.5T and 3T were not the same (1.5T: in-plane resolution: 0.625×0.94 mm2, 2-mm slice thickness for each plane [before reconstruction] and 0.86×0.86×0.86 mm3 [after reconstruction]; 3T: 0.625×0.625×1 mm3). Its impacts on segmentation results in volumetric and shape analysis require further evaluations. In the current study, we used manual segmentation trying to reduce the influences related to different resolutions. Finally, even though our premature infants had no evidence of structural brain injury on our conventional MRI scans, we cannot exclude the possibility of mild white matter impairments that are below the resolution of conventional MRI (Back, 2017; Pierson et al., 2007; Volpe, 2019), which may in turn contribute to global and regional growth impairments in the cerebrum, cerebellum and brainstem, given the reciprocal anatomical connections between the cerebrum and cerebellum. Future work will include quantitative diffusion tensor analyses to evaluate the developing white matter and long-term neurodevelopmental follow-up of our cohort.

5. Conclusion

The current study reports global and regional volumetric and shape differences of the cerebellum and brainstem in premature infants compared to healthy controls. Our findings show smaller cerebellar hemispheres and larger regional vermis and paravermis as well as smaller global and regional brainstem in premature infants compared to controls during both third trimester and term-equivalent age, suggesting that cerebellar and brainstem development is altered in premature infants, even in the absence of image evidence of brain injury. These findings provide a better understanding of cerebellar and brainstem development of premature infants, yielding important anatomical information to link with future behavioral outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the pregnant participants, infants and their families that participated in this study. We also thank all members of Center for the Developing Brain for their contributions.

Funding

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health (R01 HL116585-01, 1U54HD090257) and Thrasher Early Career Research Fund-14764.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

All authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- Alexander B, Kelly CE, Adamson C, Beare R, Zannino D, Chen J, Murray AL, Loh WY, Matthews LG, Warfield SK, others, 2019. Changes in neonatal regional brain volume associated with preterm birth and perinatal factors. Neuroimage 185, 654–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allin MPG, Salaria S, Nosarti C, Wyatt J, Rifkin L, Murray RM, 2005. Vermis and lateral lobes of the cerebellum in adolescents born very preterm. Neuroreport 16, 1821–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman NR, Naidich TP, Braffman BH, 1992. Posterior fossa malformations. Am. J. Neuroradiol 13, 691–724. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andescavage NN, du Plessis A, McCarter R, Serag A, Evangelou I, Vezina G, Robertson R, Limperopoulos C, 2016. Complex trajectories of brain development in the healthy human fetus. Cereb. Cortex 27, 5274–5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA, 2017. White matter injury in the preterm infant: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 331–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker EBE, Stoodley CJ, 2013. Autism spectrum disorder and the cerebellum, in: International Review of Neurobiology. Elsevier, pp. 1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y, 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Biran V, Verney C, Ferriero DM, 2012. Perinatal cerebellar injury in human and animal models. Neurol. Res. Int 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe H, Lee ACC, Cousens S, Bahalim A, Narwal R, Zhong N, Chou D, Say L, Modi N, Katz J, others, 2013. Preterm birth--associated neurodevelopmental impairment estimates at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatr. Res 74, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesa M, Serag A, Wilkinson AG, Anblagan D, Telford EJ, Pataky R, Sparrow SA, Macnaught G, Semple SI, Bastin ME, others, 2016. Parcellation of the healthy neonatal brain into 107 regions using atlas propagation through intermediate time points in childhood. Front. Neurosci 10, 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogovic JA, Jedynak B, Rigg R, Du A, Landman BA, Prince JL, Ying SH, 2013. Approaching expert results using a hierarchical cerebellum parcellation protocol for multiple inexpert human raters. Neuroimage 64, 616–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyssi-Kobar M, du Plessis AJ, McCarter R, Brossard-Racine M, Murnick J, Tinkleman L, Robertson RL, Limperopoulos C, 2016. Third trimester brain growth in preterm infants compared with in utero healthy fetuses. Pediatrics e20161640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazy JE, Kinney HC, Oakes WJ, 1987. Central nervous system structural lesions causing apnea at birth. J. Pediatr 111, 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechbühler C, Gerig G, Kübler O, 1995. Parametrization of closed surfaces for 3-D shape description. Comput. Vis. image Underst 61, 154–170. [Google Scholar]

- Brossard-Racine M, Du Plessis AJ, Limperopoulos C, 2015. Developmental cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome in ex-preterm survivors following cerebellar injury. The Cerebellum 14, 151– 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossard-Racine M, McCarter R, Murnick J, Tinkleman L, Vezina G, Limperopoulos C, 2018. Early extra-uterine exposure alters regional cerebellar growth in infants born preterm. NeuroImage Clin. 101646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossard-Racine M, Murnick J, Bouyssi-Kobar M, Coulombe J, Chang T, Limperopoulos C, 2017a. Altered Cerebellar Biochemical Profiles in Infants Born Prematurely. Sci. Rep 7, 8143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brossard-Racine M, Poretti A, Murnick J, Bouyssi-Kobar M, McCarter R, du Plessis AJ, Limperopoulos C, 2017b. Cerebellar microstructural organization is altered by complications of premature birth: a case-control study. J. Pediatr 182, 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong S, Rizkalla M, Du EY, West J, Risacher S, Saykin A, Shen L, 2014. Building a surface atlas of hippocampal subfields from MRI scans using FreeSurfer, FIRST and SPHARM, in: Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), 2014 IEEE 57th International Midwest Symposium On. pp. 813–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne E, 2004. Brain development in autism: early overgrowth followed by premature arrest of growth. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev 10, 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnall RA, Ariagno RL, Kinney HC, 2006. The late preterm infant and the control of breathing, sleep, and brainstem development: a review. Clin. Perinatol 33, 883–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerig G, Styner M, Jones D, Weinberger D, Lieberman J, 2001. Shape analysis of brain ventricles using spharm, in: Mathematical Methods in Biomedical Image Analysis, 2001. MMBIA 2001. IEEE Workshop On. pp. 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Geva R, Schreiber J, Segal-Caspi L, Markus-Shiffman M, 2014. Neonatal brainstem dysfunction after preterm birth predicts behavioral inhibition. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55, 802–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golalipour MJ, Ghafari S, 2012. Purkinje cells loss in off spring due to maternal morphine sulfate exposure: a morphometric study. Anat. Cell Biol 45, 121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gousias IS, Hammers A, Counsell SJ, Srinivasan L, Rutherford MA, Heckemann RA, Hajnal JV, Rueckert D, Edwards AD, 2013. Magnetic resonance imaging of the newborn brain: automatic segmentation of brain images into 50 anatomical regions. PLoS One 8, e59990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graça AM, Geraldo AF, Cardoso K, Cowan FM, 2013. Preterm cerebellum at term age: ultrasound measurements are not different from infants born at term. Pediatr. Res 74, 698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Whitfield MF, Petrie-Thomas J, Synnes AR, Cepeda IL, Keidar A, Rogers M, MacKay M, Hubber-Richard P, Johannesen D, 2009. Neonatal pain, parenting stress and interaction, in relation to cognitive and motor development at 8 and 18 months in preterm infants. Pain 143, 138–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Anand NK, Raj H, 1991. Evaluation of risk factors for hearing impairment in at risk neonates by Brainstem Evoked Response Audiometry (BERA). Indian J. Pediatr 58, 849–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldipur P, Bharti U, Alberti C, Sarkar C, Gulati G, Iyengar S, Gressens P, Mani S, 2011. Preterm delivery disrupts the developmental program of the cerebellum. PLoS One 6, e23449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson DR, Blatt GJ, 2015. Autism spectrum disorders and neuropathology of the cerebellum. Front. Neurosci 9, 420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraldsdottir K, Watson AM, Goss KN, Beshish AG, Pegelow DF, Palta M, Tetri LH, Barton GP, Brix MD, Centanni RM, others, 2018. Impaired autonomic function in adolescents born preterm. Physiol. Rep 6, e13620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernaez-Goni P, Tirapu-Ustarroz J, Iglesias-Fernandez L, Luna-Lario P, 2010. The role of the cerebellum in the regulation of affection, emotion and behaviour. Rev. Neurol 51, 597–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton LC, Yan E, Yawno T, Castillo-Melendez M, Hirst JJ, Walker DW, 2014. Injury of the developing cerebellum: a brief review of the effects of endotoxin and asphyxial challenges in the late gestation sheep fetus. The Cerebellum 13, 777–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias JE, Van Leemput K, Bhatt P, Casillas C, Dutt S, Schuff N, Truran-Sacrey D, Boxer A, Fischl B, Initiative ADN, others, 2015. Bayesian segmentation of brainstem structures in MRI. Neuroimage 113, 184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilg W, Christensen A, Mueller OM, Goericke SL, Giese MA, Timmann D, 2013. Effects of cerebellar lesions on working memory interacting with motor tasks of different complexities. J. Neurophysiol 110, 2337–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskusnykh IY, Buddington RK, Chizhikov VV, 2018. Preterm birth disrupts cerebellar development by affecting granule cell proliferation program and Bergmann glia. Exp. Neurol 306, 209–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarjour IT, 2015. Neurodevelopmental outcome after extreme prematurity: a review of the literature. Pediatr. Neurol 52, 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZD, Li ZH, 2015. Mild maturational delay of the brainstem at term in late preterm small-for-gestation age babies. Early Hum. Dev 91, 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZD, Ping LL, 2016. Functional integrity of rostral regions of the immature brainstem is impaired in babies born extremely preterm. Clin. Neurophysiol 127, 1581–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang ZD, Wang C, 2016. Small-for-gestation birth exerts a minor additional effect on functional impairment of the auditory brainstem in high-risk babies born at late preterm. Clin. Neurophysiol 127, 3187–3194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kainz B, Steinberger M, Wein W, Kuklisova-Murgasova M, Malamateniou C, Keraudren K, Torsney-Weir T, Rutherford M, Aljabar P, Hajnal JV, others, 2015. Fast volume reconstruction from motion corrupted stacks of 2D slices. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 34, 1901–1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen A, Székely G, Gerig G, 1999. Elastic model-based segmentation of 3-D neuroradiological data sets. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 18, 828–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Gano D, Ho M-L, Guo XM, Unzueta A, Hess C, Ferriero DM, Xu D, Barkovich AJ, 2016. Hindbrain regional growth in preterm newborns and its impairment in relation to brain injury. Hum. Brain Mapp 37, 678–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney HC, 2006. The near-term (late preterm) human brain and risk for periventricular leukomalacia: a review, in: Seminars in Perinatology. pp. 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan C-Y, Roth KA, Flavell RA, Rakic P, 2000. Mechanisms of programmed cell death in the developing brain. Trends Neurosci. 23, 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakopoulou V, Vatansever D, Elkommos S, Dawson S, McGuinness A, Allsop J, Molnár Z, Hajnal J, Rutherford M, 2013. Cortical overgrowth in fetuses with isolated ventriculomegaly. Cereb. Cortex 24, 2141–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K-H, Farrow TFD, Parks RW, Newton LD, Mir NU, Egleston PN, Brown WH, Wilkinson ID, Woodruff PWR, 2007. Increased cerebellar vermis white-matter volume in men with schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res 41, 645–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limperopoulos C, Bassan H, Gauvreau K, Robertson RL, Sullivan NR, Benson CB, Avery L, Stewart J, Soul JS, Ringer SA, others, 2007. Does cerebellar injury in premature infants contribute to the high prevalence of long-term cognitive, learning, and behavioral disability in survivors? Pediatrics 120, 584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limperopoulos C, Benson CB, Bassan H, Disalvo DN, Kinnamon DD, Moore M, Ringer SA, Volpe JJ, du Plessis AJ, 2005a. Cerebellar hemorrhage in the preterm infant: ultrasonographic findings and risk factors. Pediatrics 116, 717–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limperopoulos C, Chilingaryan G, Guizard N, Robertson RL, Du Plessis AJ, 2010. Cerebellar injury in the premature infant is associated with impaired growth of specific cerebral regions. Pediatr. Res 68, 145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limperopoulos C, Chilingaryan G, Sullivan N, Guizard N, Robertson RL, Du Plessis AJ, 2012. Injury to the premature cerebellum: outcome is related to remote cortical development. Cereb. Cortex 24, 728–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limperopoulos C, Soul JS, Gauvreau K, Huppi PS, Warfield SK, Bassan H, Robertson RL, Volpe JJ, du Plessis AJ, 2005b. Late gestation cerebellar growth is rapid and impeded by premature birth. Pediatrics 115, 688–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limperopoulos C, Soul JS, Haidar H, Huppi PS, Bassan H, Warfield SK, Robertson RL, Moore M, Akins P, Volpe JJ, others, 2005c. Impaired trophic interactions between the cerebellum and the cerebrum among preterm infants. Pediatrics 116, 844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makropoulos A, Aljabar P, Wright R, Hüning B, Merchant N, Arichi T, Tusor N, Hajnal JV, Edwards AD, Counsell SJ, others, 2016. Regional growth and atlasing of the developing human brain. Neuroimage 125, 456–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makropoulos A, Gousias IS, Ledig C, Aljabar P, Serag A, Hajnal JV, Edwards AD, Counsell SJ, Rueckert D, 2014. Automatic whole brain MRI segmentation of the developing neonatal brain. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 33, 1818–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathewson KJ, Van Lieshout RJ, Saigal S, Morrison KM, Boyle MH, Schmidt LA, 2015. Autonomic functioning in young adults born at extremely low birth weight. Glob. Pediatr. Heal 2, 2333794X15589560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews LG, Walsh BH, Knutsen C, Neil JJ, Smyser CD, Rogers CE, Inder TE, 2018. Brain growth in the NICU: critical periods of tissue-specific expansion. Pediatr. Res 83, 976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson C, Haslam M, Pineda R, Rogers C, Neil JJ, Inder TE, 2015. Brain injury and development in preterm infants exposed to fentanyl. Ann. Pharmacother 49, 1291–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina KL, Nagel BJ, Tapert SF, 2010. Abnormal cerebellar morphometry in abstinent adolescent marijuana users. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 182, 152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner KM, Neal EFG, Roberts G, Steer AC, Duke T, 2015. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in high-risk newborns in resource-limited settings: a systematic review of the literature. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 35, 227–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey SB, Kota S, Swisher CB, Hitchings L, Metzler M, Wang Y, Maxwell GL, Baker R, du Plessis AJ, Govindan R, 2018. Autonomic nervous system depression at term in neurologically normal premature infants. Early Hum. Dev 123, 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nino G, Govindan RB, Al-Shargabi T, Metzler M, Massaro AN, Perez GF, McCarter R, Hunt CE, du Plessis AJ, 2016. Premature infants rehospitalized because of an apparent life-threatening event had distinctive autonomic developmental trajectories. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 194, 379–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson CR, Folkerth RD, Billiards SS, Trachtenberg FL, Drinkwater ME, Volpe JJ, Kinney HC, 2007. Gray matter injury associated with periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant. Acta Neuropathol. 114, 619–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranger M, Zwicker JG, Chau CMY, Park MTM, Chakravarthy MM, Poskitt K, Miller SP, Bjornson BH, Tam EWY, Chau V, others, 2015. Neonatal pain and infection relate to smaller cerebellum in very preterm children at school age. J. Pediatr 167, 292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford MA, Bydder GM, 2002. MRI of the Neonatal Brain. WB Saunders; London. [Google Scholar]

- Sancak S, Gursoy T, Imamoglu EY, Karatekin G, Ovali F, 2016. Effect of prematurity on cerebellar growth. J. Child Neurol 31, 138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Ishigame K, Ying SH, Oishi K, Miller MI, Mori S, 2015. Macro-and microstructural changes in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 6: assessment of phylogenetic subdivisions of the cerebellum and the brain stem. Am. J. Neuroradiol 36, 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann JD, Ko R, MacMore J, 2004. The human basis pontis: motor syndromes and topographic organization. Brain 127, 1269–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann JD, Weilburg JB, Sherman JC, 2007. The neuropsychiatry of the cerebellum—insights from the clinic. The cerebellum 6, 254–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweighofer N, Lang EJ, Kawato M, 2013. Role of the olivo-cerebellar complex in motor learning and control. Front. Neural Circuits 7, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JA, Hamzelou KS, Rajagopalan V, Habas PA, Kim K, Barkovich AJ, Glenn OA, Studholme C, 2012. 3D morphometric analysis of human fetal cerebellar development. The Cerebellum 11, 761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serag A, Aljabar P, Ball G, Counsell SJ, Boardman JP, Rutherford MA, Edwards AD, Hajnal JV, Rueckert D, 2012. Construction of a consistent high-definition spatio-temporal atlas of the developing brain using adaptive kernel regression. Neuroimage 59, 2255–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Farid H, McPeek MA, 2009. MODELING THREE-DIMENSIONAL MORPHOLOGICAL STRUCTURES USING SPHERICAL HARMONICS. Evolution (N. Y) 63, 1003–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Kim S, Wan J, West J, McCullough K, Councell T, Saykin A, 2010. SPHARM-MAT Documentation [WWW Document]. URL http://www.iu.edu/~spharm/SPHARM-docs/

- Smith GC, Gutovich J, Smyser C, Pineda R, Newnham C, Tjoeng TH, Vavasseur C, Wallendorf M, Neil J, Inder T, 2011. Neonatal intensive care unit stress is associated with brain development in preterm infants. Ann. Neurol 70, 541–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steggerda SJ, Leijser LM, Wiggers-de Bruïne FT, van der Grond J, Walther FJ, van Wezel-Meijler G, 2009. Cerebellar injury in preterm infants: incidence and findings on US and MR images. Radiology 252, 190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stensvold HJ, Klingenberg C, Stoen R, Moster D, Braekke K, Guthe HJ, Astrup H, Rettedal S, Gronn M, Ronnestad AE, others, 2017. Neonatal morbidity and 1-year survival of extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics e20161821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stipdonk LW, Weisglas-Kuperus N, Franken M-CJP, Nasserinejad K, Dudink J, Goedegebure A, 2016. Auditory brainstem maturation in normal-hearing infants born preterm: a meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol 58, 1009–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovska V, Miller SL, Hooper SB, Polglase GR, 2018. The Consequences of Preterm Birth and Chorioamnionitis on Brainstem Respiratory Centers: Implications for Neurochemical Development and Altered Functions by Inflammation and Prostaglandins. Front. Cell. Neurosci 12, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley CJ, 2014. Distinct regions of the cerebellum show gray matter decreases in autism, ADHD, and developmental dyslexia. Front. Syst. Neurosci 8, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley CJ, Limperopoulos C, 2016. Structure--function relationships in the developing cerebellum: Evidence from early-life cerebellar injury and neurodevelopmental disorders, in: Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. pp. 356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley CJ, MacMore JP, Makris N, Sherman JC, Schmahmann JD, 2016. Location of lesion determines motor vs. cognitive consequences in patients with cerebellar stroke. NeuroImage Clin. 12, 765–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD, 2010. Evidence for topographic organization in the cerebellum of motor control versus cognitive and affective processing. cortex 46, 831–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD, 2009. Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage 44, 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styner M, Oguz I, Xu S, Brechbühler C, Pantazis D, Levitt JJ, Shenton ME, Gerig G, 2006. Framework for the statistical shape analysis of brain structures using SPHARM-PDM. Insight J. 242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Suzumura H, 2004. Relation between predischarge auditory brainstem responses and clinical factors in high-risk infants. Pediatr. Int 46, 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam EWY, Chau V, Ferriero DM, Barkovich AJ, Poskitt KJ, Studholme C, Fok ED-Y, Grunau RE, Glidden DV, Miller SP, 2011. Preterm cerebellar growth impairment after postnatal exposure to glucocorticoids. Sci. Transl. Med 3, 105ra105–-105ra105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco AM, Chiricozzi FR, Clausi S, Lupo M, Molinari M, Leggio MG, 2011. The cerebellar cognitive profile. Brain 134, 3672–3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkama AM, Tolonen EU, Kerttula LI, Püaukö ELE, Vainionpää LK, Koivisto ME, 2001. Brainstem size and function at term age in relation to later neurosensory disability in high-risk, preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 90, 909–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe JJ, 2019. Dysmaturation of premature brain: Importance, cellular mechanisms and potential interventions. Pediatr. Neurol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe JJ, 2009. Cerebellum of the premature infant: rapidly developing, vulnerable, clinically important. J. Child Neurol 24, 1085–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young B, 2011. Head Neck Brain Spine [WWW Document]. URL http://headneckbrainspine.com

- Yucel K, Nazarov A, Taylor VH, Macdonald K, Hall GB, MacQueen GM, 2013. Cerebellar vermis volume in major depressive disorder. Brain Struct. Funct 218, 851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker JG, Miller SP, Grunau RE, Chau V, Brant R, Studholme C, Liu M, Synnes A, Poskitt KJ, Stiver ML, others, 2016. Smaller cerebellar growth and poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in very preterm infants exposed to neonatal morphine. J. Pediatr 172, 81–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]