Abstract

To extract texture features of pulmonary nodules from three-dimensional views and to assess if predictive models of lung CT images from a three-dimensional texture feature could improve assessments conducted by radiologists. Clinical and CT imaging data for three dimensions (axial, coronal, and sagittal) in pulmonary nodules in 285 patients were collected from multiple centers and the Cancer Imaging Archive after ethics committee approval. Three-dimensional texture feature values (contourlets), and clinical and computed tomography (CT) imaging data were built into support vector machine (SVM) models to predict lung cancer, using four evaluation methods (disjunctive, conjunctive, voting, and synthetic); sensitivity, specificity, the Youden index, discriminant power (DP), and F value were calculated to assess model effectiveness. Additionally, diagnostic accuracy (three-dimensional model, axial model, and radiologist assessment) was assessed using the area under the curves for receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Cross-sectional data from 285 patients (median age, 62 [range, 45–83] years; 115 males [40.4%]) were evaluated. Integrating three-dimensional assessments, the voting method had relatively high effectiveness based on both sensitivity (0.98) and specificity (0.79), which could improve radiologist diagnosis (maximum sensitivity, 0.75; maximum specificity, 0.51) for 23% and 28% respectively. Furthermore, the three-dimensional texture feature model of the voting method has the best diagnosis of precision rate (95.4%). Of all three-dimensional texture feature methods, the result of the voting method was the best, maintaining both high sensitivity and specificity scores. Additionally, the three-dimensional texture feature models were superior to two-dimensional models and radiologist-based assessments.

Keywords: Three dimensions, Pulmonary nodule, Contourlets, Predictive model

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer, resulting in over a million deaths per annum worldwide [1]. Malignant pulmonary nodules can be difficult to be recognized, which are similar to benign nodules, especially in early-stage lung cancer. The predictive result is poor with 5-year survival rates approaching 10% in most countries [2]. However, if cancer could be detected early at clinical stage I, the 10-year survival rate could be greatly improved [3]. It is therefore highly desirable to improve the recognition rate of benign and malignant pulmonary nodules in their initial stages. Computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) has become an important auxiliary diagnostic tool, with which researches can identify an individual’s early-stage lung cancer in recent years [4–11]. Pathological changes in individuals are often reflected by changes on texture features of medical images; therefore, researchers have tried using the texture analysis technique for a variety of medical image analysis in the CAD system to explore new avenues for diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Texture extraction is a key step in the CAD system for texture is a fundamental characteristic of digital images [12]. Almost all of the computerized schemes use texture extraction methods such as multi-scale methods wavelets or co-occurrence matrixes to get the characteristics of pulmonary nodules. Based on previous studies, CAD system also has limitations such as fails to diagnose subtle regions and high false positives [13]. Analysis using wavelet transformation on an image with traditional 2D cannot accurately reflect the directions of the image edges. However, second-generation wavelet transformation (such as contourlets) is more suitable for analysis of characterizing 2D curves or edges in images and has the capability to approximate accuracy and better sparse communication power. The basic idea is to obtain stable texture features at low-resolution images, identify different texture regions, and precisely position at high resolution to get the texture edge and true position, then track the image from coarse to fine quality, and finally get the actual texture areas of the image. They have been implemented in various medical applications [14–17]. An image can be decomposed into several scales with more detailed and precise information than traditional methods [18–20]. However, pulmonary nodules have three-dimensional structures; previous studies based on contourlets were limited to two-dimensional analysis, contourlets, which could capture the intrinsic geometrical structure of pulmonary nodule images. Its basic idea was to use a multi-scale decomposing as wavelet-like to capture singular points of contour for images and put the close singular points to integrate contour segment according to the direction information. To the best of our knowledge, contourlets have not been reported to date in any image analysis of lung cancer.

The aims of this study are to propose a new textural feature extraction method from three dimensions measured image and extend contourlet textures from two dimensions to three. This method is expected to better describe the properties of pulmonary nodules and get relatively high precision for pulmonary nodule prediction. Also, four evaluation methods were used for final assessments.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study was a cross-sectional municipal multicenter and diagnostic accuracy study performed in 2009. Overall, we collected sample information from 115 males (40.4% of all patients, median age [range] 62[45–83]) and 170 female patients (59.6% of all patients, median age [range] 62[45–81]) who underwent a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the lungs. Five hundred two patients (only from axial view) have been previously reported [21]. This prior article dealt with two-dimensional features whereas, in this manuscript, we report on three-dimensional texture features of pulmonary nodules for prognostic models. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval Document No. [2011] 01). All subjects provided informed consent. Questionnaire information and patient checked information including seven demographic characters and twelve pulmonary nodule morphological features were collected in this study. Demographic parameters included age, gender, smoking habits, tuberculosis history, dust history, genetic disease, and tumor history. Morphological features included calcification, cavitation, density, ground-glass appearance, lobulation, lymph node status, margin size, presence of vacuoles, pleural indentation and pleural fluid, diameter, and substantial changes. We used the inclusion and exclusion criteria in this study. Inclusion criteria included the following: (1) age should be equal to or above 45 years, (2) every image should be in DICOM image format, (3) every nodule’s size should between 0.3 and 3.0 cm, (4) every scanning should use a 64-slice helical CT scanner (Sensation Somatom Cardiac) with a tube voltage of 120 kV and a current of 100 mA, (5) every patient should have more than or equal to five CT images for each patient with nodules, (6) diagnosis of malignant nodules should comply with pathological evidences, for benign nodules, patients should have been followed up for more than 2 years without the appearance of the transformed malignant nodules or no further development. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) patients have incomplete personal information, (2) with no pathological diagnosis or follow-up times were less than 2 years, (3) nodule segmentation that was difficult to extract.

CT Imaging

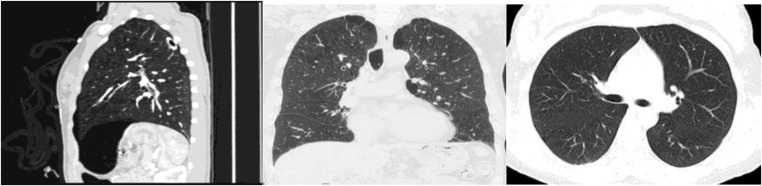

A 64-slice helical CT scanner (Sensation Somatom Cardiac) with a tube voltage of 120 kV and a current of 100 mA were used in this study. The reconstruction thickness and reconstruction intervals for routine scanning were 5 mm. The kernel was B70/B30. All of the pulmonary nodules in the CT images were segmented manually by radiologists to obtain a region of interest (ROI) and the textural features were extracted. The region grow algorithm, a popular tool for imaging segmentation, was used to remove any background pixels such as muscle and blood vessels. The picture of 3D pulmonary nodules was shown in Fig. 1, and the axial, coronal, and sagittal CT image were shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

The picture of 3D pulmonary nodules

Fig. 2.

The axial, coronal, and sagittal CT image

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square test was used to determine differences among demographic characteristic morphological features between malignant and benign pulmonary nodules. Contourlets [12] was used to extract features from three-dimensional (axial, coronal, and sagittal views) CT images, which include two steps: a Laplacian pyramid (LP) and a directional filter bank (DFB). Some studies have shown that the contourlet transformation has better performance than other multi-scale methods [18, 21]. Support vector machine (SVM) was used to build predictive models, and Laplacian was selected as the kernel function. This algorithm showed many advantages in solving small-sample, nonlinear, and high-dimensional pattern recognition problems; to some extent, it overcame the “curse of dimensionality,” “over-learning,” and other issues.

Contourlets

The wavelet transform, a popular textural feature extraction method, provides a non-redundant representation of signals. However, it has a limitation, namely, it is not adequate for representing one-dimensional singularities. To overcome the limitations of the wavelet transform, Do and Vetterli developed the contourlet transform, which shares many features with its wavelet counterpart but with the addition of an efficient representation of two-dimensional images. It is considered to be a true image processing tool for two-dimensional images. Contourlet transformations include two steps: a Laplacian pyramid (LP) and a directional filter bank (DFB). At last, we calculated 14 eigenvalues in 96 sub-bands, resulting in 1344 textural features values.

Some studies have shown that the contourlet transformation has better performance than other multi-scale methods.

Support Vector Machine

Support vector machine (SVM) was a classification algorithm which could achieve optimal classification for linear separable data. This algorithm could be implemented in R software, which was free statistical software for various algorithms; many free packages for these algorithms were shared on the internet. All processes have spent 30 min, so it takes 0.3 s to process one CT nodule case.

Comprehensive Evaluation

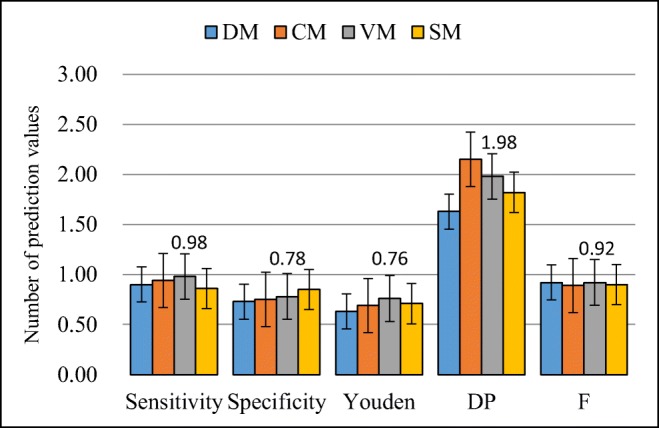

Twenty-fold cross-validation (CV) was used to evaluate SVM predictive models. Three different predictive models were built on axial data, coronal data, and sagittal data separately. According to the evaluation results, to calculate evaluating indicators, see Fig. 4. As a result, each CT images for each patient had three predictive results (from axial coronal and sagittal views). Use four comprehensive evaluation methods to confirm the final results.

Fig. 4.

Three dimensions predicting results for the four comprehensive evaluation methods based on SVM classifier. DM, CM, VM, and SM representing the junctive, conjunctive, voting, and synthetic methods, respectively

Four comprehensive evaluation methods were used to evaluate the prediction accuracy. [1] Voting method: To establish three prediction models for the axial, coronal, and sagittal positions, it is possible to obtain benign and malignant forecast results in the same patient in three directions. Select the result (two or more results regarding the model’s prediction) cases as the final prediction result. [2] Disjunctive method: To establish three prediction models for the axial, coronal, and sagittal positions, it is possible to obtain benign and malignant forecast results in the same patient in three directions. If the prediction model results are judged to be malignant, the patient is eventually judged to have a malignant result; otherwise, they are judged to have a benign result. [3] Conjunctive method: To establish three prediction models for the axial, coronal, and sagittal positions, it is possible to obtain benign and malignant forecast results in the same patient in three directions. Only if the three prediction models were judged as malignant results did patients finally be judged as malignant results, otherwise they were judged to have a benign result. [4] Comprehensive method: This method involves merging the axial, coronal, and sagittal data sets, and building a predictive model; the findings are viewed as the final result.

Assessment Criteria

Five statistical indexes were calculated to evaluate the predictive results for all datasets, including sensitivity, specificity, Youden index, discriminant power, and F scores. Also, the area under the curves (AUCs) was calculated to establish the receiver operating characteristic (ROC).

Computational method of discriminant power (DP):

Computational method of F scores:

- Tp

was represented as a number of malignant nodules were correctly classified as a malignant nodule.

- Fn

was represented as a number of malignant nodules were correctly classified as a malignant nodule.

- Tn

was represented as a number of malignant nodules were correctly classified as a malignant nodule.

- Fp

was represented as a number of malignant nodules were correctly classified as a malignant nodule.

Varies of β scores had an influence on F values. When β > 1, F scores tend to be sensitivity; when β < 1, F scores tend to be specificity; β = 1, F scores both sensitivity and specificity. In our study, we choose β = 1.

Results

A total of 285 eligible patients were included in our study; no subjects were excluded. Baseline characteristics are shown in Tables 1, 2, and 3. There was a significant difference in the age (P < 0.001) in demographic parameters between malignant and benign groups. Smoking habits, tuberculosis history, dust history, genetic disease, and tumor history have no significant difference between the two groups. In morphological features, there was a significant difference on calcification, ground glass, lobulation, lymph node status, margin, vacuoles, pleura indentation, diameter, and substantial changes between malignant and benign groups; other morphological features have no significant difference between two groups.

Table 1.

Age distribution of five age groups

| Age (y) | n | Male/female |

|---|---|---|

| 45–49 | 33 | 13/20 |

| 50–59 | 92 | 41/51 |

| 60–69 | 85 | 38/47 |

| 70–79 | 69 | 22/47 |

| 80–83 | 5 | 1/4 |

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at study inclusion

| Malignant | Benign | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | < 0.001 | |||

| All patients | ||||

| Median (range) | 62(45–83) | |||

| Interquartile range | 55–69 | |||

| Men (%) | 92(32.3) | 23(8.1) | ||

| Median (range) | 62(45–83) | |||

| Interquartile range | 55–68 | |||

| Women (%) | 131(46.0) | 39(13.7) | ||

| Median | 62(45–81) | |||

| Interquartile range | 54–70 | |||

| Smoking habits | 0.094 | |||

| Yes (%) | 139(48.8) | 18(6.3) | ||

| No (%) | 84(29.5) | 44(15.4) | ||

| Tuberculosis history | 0.791 | |||

| Yes (%) | 12(4.2) | 3(1.1) | ||

| No (%) | 211(74.0) | 59(20.7) | ||

| Dust history | 0.984 | |||

| Yes (%) | 4(1.4) | 1(0.4) | ||

| No (%) | 219(76.8) | 61(21.4) | ||

| Genetic disease | 0.451 | |||

| Yes (%) | 3(1.1) | 0(0) | ||

| No (%) | 220(77.2) | 62(21.8) | ||

| Tumor history | 0.141 | |||

| Yes (%) | 15(5.3) | 1(0.4) | ||

| No (%) | 208(73.0) | 61(21.4) | ||

Table 3.

Morphological features at study inclusion

| malignant | benign | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcification | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes (%) | 23(8.1) | 7(2.5) | |

| No (%) | 200(70.2) | 55(19.3) | |

| Cavitations | 0.5098 | ||

| Yes (%) | 23(8.1) | 5(1.8) | |

| No (%) | 200(70.2) | 57(20.0) | |

| Dentity | 0.321 | ||

| Yes (%) | 137(48.1) | 40(14.0) | |

| No (%) | 86(30.2) | 22(7.7) | |

| Ground glass | 0.004 | ||

| Yes (%) | 18(6.3) | 2(0.7) | |

| No (%) | 205(71.9) | 60(21.1) | |

| Lobulation | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes (%) | 178(62.5) | 48(16.8) | |

| No (%) | 45(15.8) | 14(4.9) | |

| Lymph node status | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes (%) | 72(25.2) | 11(3.9) | |

| No (%) | 151(53.0) | 51(17.9) | |

| Margin | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes (%) | 166(58.2) | 44(15.4) | |

| No (%) | 57(20.0) | 18(6.3) | |

| Vacuoles | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes (%) | 34(11.9) | 12(4.2) | |

| No (%) | 189(66.3) | 50(17.5) | |

| Pleura indentation | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes (%) | 68(23.9) | 20(7.0) | |

| No (%) | 155(54.4) | 42(14.7) | |

| Pleural fluid | 0.234 | ||

| Yes (%) | 22(7.7) | 6(2.1) | |

| No (%) | 201(70.5) | 56(19.6) | |

| Diameter | < 0.001 | ||

| Mean(Std) | 2.31(0.72) | 1.7(0.67) | |

| Substantial changes | 0.001 | ||

| Yes (%) | 201(70.5) | 60(21.1) | |

| No (%) | 22(7.7) | 2(0.7) | |

SVM Classification Analysis

The SVM prediction results from axial, coronal, and sagittal view respectively were shown in Fig. 3. For axial predictive model, we get the best sensitivity (0.94) scores of three two-dimensional models. For coronal predictive model and sagittal predictive model, we get relatively low scores, sensitivity 0.85, specificity 0.75, and sensitivity 0.75, specificity 0.78.

Fig. 3.

Two dimensions predicting results from an axial view, coronal view, and sagittal view based on SVM classifier

The SVM prediction results from the three-dimensional model using different evaluation methods were in Fig. 4. In our study, the voting method has better results with sensitivity (0.98), specificity (0.78), Youden index (0.76), and F (0.92) scores. For synthetic method, we get high specificity score of 0.85. DP value was best in the conjunctive method of 2.13. The results are plotted in Fig. 4.

The early diagnosis of lung cancer depends on whether to make a correct judgment for the probability of pulmonary nodule transformed into malignant ones. Although pulmonary nodules are difficult to identify by naked eyes; texture parameter extracted from pulmonary nodules can be a more comprehensive description of the essential characteristics of such nodules. Texture feature as a kind of internal characteristics of images often reflects the microscopic characteristics of pulmonary nodules; the morphological characteristics reflect the pulmonary nodule characteristics as a whole. Neither ignore what part will cause the loss of information and not a comprehensive description of the characteristics of nodules. So we put both texture features and morphological characteristics in predictive models to predict of benign and malignant pulmonary nodules. In our study, we adopt the SVM classifier as the prediction model to find an optimal separating hyperplane that could satisfy the requirement of classification, making the hyperplane to ensure the classification accuracy at the same time and maximize the blank space on either side of the hyperplane. In theory, SVM for linear fraction can be implemented according to the optimal classification. That is, according to the difference of texture features and morphological features of benign and malignant pulmonary nodules, the SVM classifier classifies the transferred malignant nodules and benign nodules through texture feature characteristics and morphological characteristics. The significance of SVM auxiliary diagnosis is to evaluate whether pulmonary nodules have become malignant in the early stage of lung cancer and improve the doctor's attention to patients' treatment. It could not eliminate some follow-up CT scans, biopsies, and some other pathological evidence for malignant nodules.

Radiologist-Based Assessments

Three radiologists were selected to diagnose 285 cases, including patient age, gender, and other information regarding malignant diagnosis. The diagnosis level was divided into five scores: Score 1, benign diagnosis; Score 2, uncertain diagnosis, but benign tendency; Score 3, uncertain diagnosis; Score 4, uncertain diagnosis, but malignant tendency; Score 5, malignant diagnosis. For the first radiologist, we could get sensitivity (0.70) and specificity (0.83) scores. For the second radiologist, we could get sensitivity (0.73) and specificity (0.58) scores. For the third radiologist, we could get sensitivity (0.72) and specificity (0.51) scores.

Comparison Between SVM Classification Analysis and Radiologist-Based Assessments

The results of the SVM predictions from two dimensions and three dimensions and radiologist-based assessments are shown in Fig. 5 and Table 3. For stronger sensitivity and specificity scores, we can use Youden index (sensitivity + specificity − 1) to set the threshold. For the radiologist-based assessment, when the Youden index is 0.53, we can get relatively stronger sensitivity (0.70) and specificity (0.83) scores. For SVM classifier for axial view, when the Youden index is 0.71, we can get relatively stronger sensitivity (0.94) and specificity (0.73) scores. For SVM classifier from three-dimensional views, for stronger specificity, we choose the Youden index (0.76), we can get relatively stronger sensitivity (0.98) and specificity (0.78) scores. We can see that when the sensitivity scores of axial texture feature model and three-dimensional texture feature model are the same, the three-dimensional texture feature model could get better specificity (Tables 4 and 5).

Fig. 5.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROCs) plots of the axial predictive result, comprehensive method result, and radiologist-based assessment data

Table 4.

The area under the curves (AUCs) and 95% CIs

| AUC | P | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axial | 0.895 | < 0.001 | 0.836 to 0.953 |

| Comprehensive | 0.907 | < 0.001 | 0.849 to 0.964 |

| Radiologist | 0.657 | < 0.001 | 0.583 to 0.731 |

Table 5.

The difference testing of three methods

| D of areas | Z statistic | P | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axial vs. Com | 0.012 | 0.964 | 0.335 | − 0.012 to 0.037 |

| R vs. Com | 0.250 | 5.746 | < 0.001 | 0.164 to 0.335 |

| R vs. Axial | 0.238 | 5.428 | < 0.001 | 0.152 to 0.323 |

Com means comprehensive method and R means radiologist

Discussion

Our study aimed to extract texture features from comprehensive axial, coronal, and sagittal views, as an alternative to radiologist-based pulmonary nodule evaluation. The study demonstrated that both the sensitivity and specificity regarding SVM classifier were higher than the radiologist-based diagnosis. The sensitivity of the disjunctive, conjunctive, voting, and synthetic methods was increased by 20%, 24%, 28%, and 16%, respectively, for the radiologist 1; by 17%, 21%, 25%, and 13%, respectively, for the radiologist 2; and by 18%, 22%, 26% and 14%, respectively, for the radiologist 3. The specificity of the disjunctive, conjunctive, and voting method was decreased compared with radiologist 1 and but increased compared with radiologists 2 and 3; the specificity of synthetic methods was increased by 2% for radiologist 1, the specificity of disjunctive, conjunctive, voting, and synthetic methods was increased by 15%, 17%, 20%, and 27%, respectively, for radiologist 2, and by 22%, 24%, 27% and 34%, respectively, for radiologist 3.

In general, prediction accuracy predictive model based on three dimensions are higher than that based on two dimensions. And for the three models based on two-dimensional texture features, the axial predictive model has both higher sensitivity and specificity scores, which describes better for nodules’ information. While from a sagittal view, it has the best specificity.

Of the four comprehensive evaluation methods, the disjunctive method was found to have a higher F value, and the conjunctive method a higher specificity, DP value, and Youden index. Thus the disjunctive evaluation method could improve the specificity of the forecasting model, but it would reduce the sensitivity of the model. The conjunctive method had the opposite effect. The voting method had both better sensitivity and specificity from the comprehensive aspect because it could be used to select the majority of the results as the final ones; this method gives relatively conservative results. The synthetic method did not prove to be as good as the voting method and to some extent may lose information.

During the radiologist-based diagnosis, the accuracy of benign nodule recognition was higher than was the case for malignant nodules; this may have been the reason why the specificity of radiologist 1 and radiologist 2 was superior to that achieved using the disjunctive method. The fact that radiologist diagnosis had a lower sensitivity for malignant nodules was the result of malignant nodules being difficult to identify. Machine learning could aid radiologist-based diagnosis and help improve diagnostic precision.

Conclusion

In conclusion of the three-dimensional image evaluation methods, the capacity of the voting method evaluation proved to be the highest and could maintain both high sensitivity and specificity. In addition, the performance of the machine learning diagnosis was found to be superior to radiologist-based diagnosis.

Appendix

Contourlets

The LP is a multi-scale decomposition of the L2(R2) space into a series of increasing resolutions as given by Eq. 1.

| 1 |

where Vj0 is an approximation sub-space at the scale 2j0, whereas Wj contains the added details at the finer scale 2j − 1. In the LP, each sub-space Wj is spanned by a frame {μj, n(t)}, n ∈ z2 that assimilates a uniform grid on R2 at intervals 2j − 1 × 2j − 1. For the directional filter bank, it can be shown that a l-level DFB generates a local directional basis for L2(Z2) that is composed of the impulse responses of the 2l directional filters and their shifts (Eqs. 2 and 3, respectively).

| 2 |

| 3 |

In the contourlet transform, suppose that a lj level DFB is applied to the detail sub-space Wj of the LP as in Eq. 4.

| 4 |

Each sub-space is spanned by a frame with a redundancy ratio of 4:3, where . Furthermore, is generated from a single prototype function and its shifts: .

SVM

The objective of SVM is to find a mechanism to meet the classification requirements of the optimal separating hyperplane, such that the hyperplane can be maximized over a blank area on both sides of the plane while ensuring the classification accuracy.

In theory, the SVM can achieve the optimal linear separately regarding two types of data classification, for example, a given training set (xi, yj), i = 1, 2, ..., l, x ∈ {±1}, where the hyperplane is denoted as (w • x) + b = 0. To classify the face of all samples correctly and to classify the interval would require meeting the following constraints,yi[(w • xi) + b] ≥ 1, i = 2, 2, ...l. The classification interval can be calculated as 2/‖w‖. Therefore, the problem of optimal hyperplane structure is transformed for the sake of constraints under:

| 5 |

To address this constraint optimization problem, the Lagrange function is introduced:

| 6 |

where αi > 0 is the Lagrange multiplier.

| 7 |

| 8 |

In the above dual problem, to avoid complex computing and high-dimensional inner products, it needs to be established if it is the objective function or decision-making functions that only relate to the product operation between the training samples in high-dimensional space.

Funding

Natural Science Fund of China (Serial Nos.: 81172772, 81773542 and 81373099) and the Natural Science Fund of Beijing (Serial Nos.: 4112015 and 7131002),The Program of Natural Science Fund of Beijing Municipal Education Commission (Serial Number: KZ201810025031).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (Approval Document No. [2011] 01). All subjects provided informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Advances in Knowledge

This study provides evidence that analysis of three-dimensional pulmonary nodule texture features on CT images performance could be a more comprehensive description of the nature of pulmonary nodules, better than radiologist-based assessments.

Statistical methods, including contourlets and SVM classifier from three dimensions, were used to evaluate the likelihood of a nodule being malignant.

Based on three-dimensional texture feature models, we could improve both sensitivity and specificity scores regarding radiologist diagnosis for 23% and 28% respectively, which could assist to radiology to diagnose lung cancer.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ni Gao and Sijia Tian contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Sijia Tian, Email: hbtsj2012@126.com.

Xiuhua Guo, Email: guoxiuh@ccmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures 2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mountzios G, Dimopoulos MA, Soria JC, Sanoudou D, Papadimitriou CA. Histopathologic and genetic alterations as predictors of response to treatment and survival in lung cancer: A review of published data. Crit Rev OncolHematol. 2010;75(2):94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seki N, Eguchi K, Kaneko K, et al. The adenocarcinoma-specific stage shift in the Anti-lung Cancer Association project: Significance of repeated screening for lung cancer for more than 5 years with low-dose helical computed tomography in a high-risk cohort. Lung Cancer. 2010;67(3):318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, Guo XH, Jia ZW, Li HK, Liang ZG, Li KC, He Q. Multilevel binomial logistic prediction model for malignant pulmonary nodules based on texture features of CT image. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(1):124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eltoukhy MM, Faye I, Samir BB. Breast cancer diagnosis in digital mammogram using multiscale curvelet transform. Comput Med Imaging and Graph. 2010;34:269–227. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo D, Qiu T, Bian J, Kang W, Zhang L. A computer-aided diagnostic system to discriminate SPIO-enhanced magnetic resonance hepatocellular carcinoma by a neural network classifier. Comput Med Imaging and Graph. 2009;33(8):588–592. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu YN, Wang H, Guo XH, et al. A comparison between inside and outside texture features extracting from pulmonary nodules of CT images, natural computation, 2009. ICNC '09. Fifth International Conference. 2009;6:183–186. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu YJ, Tan YQ, Hua YQ, Wang M, Zhang G, Zhang J. Feature selection and performance evaluation of support vector machine (SVM)-based classifier for differentiating benign and malignant pulmonary nodules by computed tomography. J Digit Imaging. 2010;23(1):51–65. doi: 10.1007/s10278-009-9185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh C, Lin CL, Wu MT, Yen CW, Wang JF. A neural network-based diagnostic method for solitary pulmonary nodules. Neurocomputing. 2008;72:612–624. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2007.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Way TW, Sahiner B, Chan HP, et al. Computer-aided diagnosis of pulmonary nodules on CT scans: Improvement of classification performance with nodule surface features. Med Phys. 2008;36(7):3086–3098. doi: 10.1118/1.3140589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chabat F, Yang GZ, Hansell DM, et al. Obstructive lung diseases: texture classification for differentiation at CT. Radiology. 2003;228(3):871–877. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2283020505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Do MN, Vetterli M. The contourlet transform: an efficient directional multiresolution image representation. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2005;14(12):2091–2106. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2005.859376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohamed ME, Ibrahima F, Brahim B. A comparison of wavelet and curvelet for breast cancer diagnosis in digital mammogram. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2010;40:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahimi F, Rabbani H. A dual adaptive watermarking scheme in contourlet domain for DICOM images. Biomed Eng Online. 2011;10:53. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai NC, Chen HW, Hsu SL. Computer-aided diagnosis for early-stage breast cancer by using wavelet transform. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2011;35(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsantis S, Dimitropoulos N, Cavouras D, Nikiforidis G. Morphological and wavelet features towards sonographic thyroid nodules evaluation. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2009;33(2):91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandal T, Wu QMJ, Yuan Y. Curvelet based face recognition via dimension reduction. Signal Processing. 2009;89:2345–2353. doi: 10.1016/j.sigpro.2009.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Azzawi N, Sakim HA, Abdullah AK, et al. Medical image fusion scheme using complex contourlet transform based on PCA. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2009: 5813–5816. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Eltoukhy MM, Faye I, Samir BB. Breast cancer diagnosis in digital mammogram using multiscale curvelet transform. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2010;34(4):269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dettori L, Semler L. A comparison of wavelet, ridgelet, and curvelet-based texture classification algorithms in computed tomography. Comput Biol Med. 2007;37(4):486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jingjing W, Tao S, Ni G, et al. Contourlet texture feartures: improving the diagnosis of solitary pulmonary nodules in two dimensional CT images. Plos One. 2014;9(9):e108465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hai J, Tan H, Chen J, Wu M, Qiao K, Xu J, Zeng L, Gao F, Shi D, Yan B. Multi-level features combined end-to-end learning for automated pathological grading of breast cancer on digital mammograms[J] Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2019;71:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma Y, Feng W, Wu Z, Liu M, Zhang F, Liang Z, Cui C, Huang J, Li X, Guo X. Intra-tumoral heterogeneity characterization through texture and color analysis for differentiation of non-small cell lung carcinoma subtypes. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:165018. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aad648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kermany DS, Goldbaum M, Cai W, Valentim CCS, Liang H, Baxter SL, McKeown A, Yang G, Wu X, Yan F, Dong J, Prasadha MK, Pei J, Ting MYL, Zhu J, Li C, Hewett S, Dong J, Ziyar I, Shi A, Zhang R, Zheng L, Hou R, Shi W, Fu X, Duan Y, Huu VAN, Wen C, Zhang ED, Zhang CL, Li O, Wang X, Singer MA, Sun X, Xu J, Tafreshi A, Lewis MA, Xia H, Zhang K. Identifying medical diagnoses and treatable diseases by image-based deep learning. Cell. 2018;172(5):1122–1131.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]