Abstract

The accuracy of commercially available tests for COVID-19 in Brazil remains unclear. We aimed to perform a meta-analysis to describe the accuracy of available tests to detect COVID-19 in Brazil. We searched at the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) online platform to describe the pooled sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) and summary receiver operating characteristic curves (SROC) for detection of IgM/IgG antibodies and for tests using naso/oropharyngeal swabs in the random-effects models. We identified 16 tests registered, mostly rapid-tests. Pooled diagnostic accuracy measures [95%CI] were: (i) for IgM antibodies Se = 82% [76–87]; Sp = 97% [96–98]; DOR = 168 [92–305] and SROC = 0.98 [0.96–0.99]; (ii) for IgG antibodies Se = 97% [90–99]; Sp = 98% [97–99]; DOR = 1994 [385–10334] and SROC = 0.99 [0.98–1.00]; and (iii) for detection of SARS-CoV-2 by antigen or molecular assays in naso/oropharyngeal swabs Se = 97% [85–99]; Sp = 99% [77–100]; DOR = 2649 [30–233056] and SROC = 0.99 [0.98–1.00]. These tests can be helpful for emergency testing during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. However, it is important to highlight the high rate of false negative results from tests which detect SARS-CoV-2 IgM antibodies in the initial course of the disease and the scarce evidence-based validation results published in Brazil. Future studies addressing the diagnostic performance of tests for COVID-19 in the Brazilian population are urgently needed.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus, Diagnostic accuracy

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as pandemic on March 11, 2020. Due to the rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viruses, we are currently facing a scenario of sustained community transmission of COVID-19 worldwide.1 Early implementation of mitigation associated with suppression strategies can drastically reduce the number of hospitalizations and deaths.2 Large-scale testing, rapid diagnosis and immediate isolation of cases coupled with rigorous tracking and preventive self-isolation of close contacts are essential measures to reduce the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Therefore, tests for COVID-19 should be point-of-care, widely available, and implemented outside of hospital settings to prevent overwhelming the health care system as well as the risk of nosocomial transmission to other patients and healthcare workers. Results from the mathematical modeling study performed by the Imperial College of London for Brazil, the implementation of suppression strategies could save up to a million lives and prevent the collapse of the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, SUS) compared to an unmitigated strategy.4 Though massive testing is a cornerstone to reduce the burden of COVID-19, the accuracy of commercially available tests for COVID-19 in Brazil remains unclear. The aim of this study was to perform a meta-analysis to describe the accuracy of available tests to detect COVID-19 in Brazil.

To identify the registered tests for COVID-19 diagnosis in Brazil, we performed searches on March 30, 2020 using the following terms “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “coronavirus” at the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, ANVISA, website: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/saude/). Data were extracted by two independent researchers to an electronic database. The identified tests were stratified according to those which detect SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin antibodies (IgM and/or IgG) and nucleic acid (RNA) or antigen (Ag) from SARS-CoV-2. The following data were extracted from documents uploaded by manufacturers for each registered test: test name, ANVISA registry number, type of sample, type of analysis, type of assay and data of the diagnostic value of each test as reported by the manufacturer [number of true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN) and false negative (FN)].

Diagnostic performance for the detection of IgM and IgG antibodies was analyzed separately for each test. Detection of IgM antibodies is often interpreted as an indicator of acute infection while the detection of IgG antibodies represents previous infection/immunity. Sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were described. Data synthesis was performed using univariate mixed-effects logistic regression models with maximum likelihood estimation based on adaptive Gaussian quadrature using xtmelogit (midas package) from STATA for Windows (2017; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).5 Pooled Se, Sp, positive likelihood ratio (LR+), negative likelihood ratio (LR−) and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) are described for IgM antibodies, IgG antibodies and for tests using nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal swabs for SARS-CoV-2 detection in the random-effects models. Forest plots with test-specific and overall point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were provided with Cochran's Q and I2 heterogeneity statistics. Summary receiver operating characteristic curves (SROC) were plotted with the presentation of a summary operating point, 95% confidence and prediction contours.

A total of 16 tests for detection of COVID-19 registered in the ANVISA's online platform were identified. Out of these, 11 tests detect SARS-CoV-2 N-Protein IgM and/or IgG antibodies [nine for IgM/IgG; one for IgM and one for IgG detection] in human serum, plasma, whole blood (or finger prick samples); three detect the nucleic acid (RNA) and two detect the antigen (Ag) of SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal swabs. All tests considered molecular assays as the gold standard. In addition, 11 tests are considered as point-of-care (POC) tests: nine detecting IgM/IgG antibodies in finger prick sample and two detecting SARS-CoV-2 Ag in nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal swabs. A total of seven tests are imported from the following countries: China (n = 4), United States of America (n = 2), and Spain (n = 1) tests (Supplementary Table 1). Table 1 summarizes the diagnostic performance of each test as reported by the manufacturer. Data of positive/negative samples were not divided by IgM/IgG antibodies analysis for two tests, and the manufacturer did not report the number of TP, FP, TN and FN for a swab test [these tests were excluded from the pooled diagnostic analysis].

Table 1.

Characteristics of tests for COVID-19 registered at the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) up to March 30, 2020.

| COVID-19 test characteristics | Type | POC-test | Result (min) | n | Se (%) | Sp (%) | TP (n) | FP (n) | TN (n) | FN (n) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CORONAVIRUS IgG/IgM (COVID-19) ANVISA registry number: 10159820239 Samples: fingertip blood, serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgG | Yes | 20 | 70 | 100 | 98 | 20 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 95 | 100 |

| IgM | Yes | 20 | 70 | 85 | 96 | 17 | 2 | 48 | 3 | 89 | 94 | |

|

ECO F COVID-19 Ag ANVISA registry number: 80954880131 Samples: nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs Type: immunofluorescence assay |

Ag | Yes | 30 | 100 | 86 | 95 | 30 | 5 | 62 | 3 | 86 | 95 |

|

COVID-19 IgG/IgM ECO Test ANVISA registry number: 80954880132 Samples: fingertip blood, serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgG | Yes | 10 | 70 | 95 | 99 | 20 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 95 | 100 |

| IgM | Yes | 10 | 70 | 90 | 94 | 17 | 2 | 48 | 3 | 89 | 94 | |

|

COVID-19 Ag ECO Test ANVISA registry number: 80954880133 Samples: nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs Type: immunochromatographic assay |

Ag | Yes | 15 | 80 | 70 | 97 | 17 | 8 | 53 | 2 | 68 | 96 |

|

Anti-COVID-19 IgG/IgM Rapid Test ANVISA registry number: 10009010356 Samples: fingertip blood, serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgG | Yes | 10 | 70 | 100 | 98 | 20 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 95 | 100 |

| IgM | Yes | 10 | 70 | 85 | 96 | 17 | 3 | 48 | 2 | 85 | 96 | |

|

LUMIRATEK COVID-19 (IgG/IgM) ANVISA registry number: 81327670112 Samples: fingertip blood, serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgG | Yes | 10 | 181 | 97.4 | 98.9 | 37 | 1 | 142 | 1 | 97 | 99 |

| IgM | Yes | 10 | 181 | 86.8 | 98.6 | 33 | 2 | 141 | 5 | 94 | 97 | |

|

MedTeste Coronavirus (COVID-19) IgG/IgM ANVISA registry number: 80560310056 Samples: fingertip blood, serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgG | Yes | 10 | 181 | 97.4 | 99.3 | 37 | 1 | 142 | 1 | 97 | 99 |

| IgM | Yes | 10 | 181 | 86.8 | 98.6 | 33 | 2 | 141 | 5 | 94 | 97 | |

|

FAMÍLIA KIT XGEN MASTER COVID-19 – SARS-CoV-2 ANVISA registry number: 80502070088 Samples: nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs Type: RT-PCR |

RT-PCR | No | NA | NR | 95 | 100 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

DPP® COVID-19 IgM/IgG System ANVISA registry number: 80535240052 Samples: fingertip blood, serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgG | Yes | 5 | 20 | 77.8 | 100 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 100 | 33 |

| IgM | Yes | 5 | 20 | 55.6 | 100 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 100 | 20 | |

|

Smart Test Covid-19 Vyttra ANVISA registry number: 81692610175 Samples: fingertip blood, serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgM/IgG | Yes | 10 | 10 | 100 | 99.5 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

|

VIASURE SARS-CoV-2 ANVISA registry number: 10355870373 Samples: nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs Type: RT-PCR |

RT-PCR | No | NA | 134 | 100 | 100 | 35 | 0 | 98 | 1 | 100 | 99 |

|

Cobas SARS-CoV-2 ANVISA registry number: 10287411491 Samples: nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs Type: RT-PCR |

RT-PCR | No | NA | 150 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

|

Teste Rápido em Cassete 2019-nCoV IgG/IgM ANVISA registry number: 81325990117 Samples: fingertip, serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgG | Yes | 10 | 70 | 100 | 98 | 20 | 1 | 49 | 0 | 95 | 100 |

| IgM | Yes | 10 | 70 | 85 | 96 | 17 | 2 | 48 | 3 | 89 | 94 | |

|

MAGLUMI IgG de 2019-nCoV (CLIA) ANVISA registry number: 80102512430 Samples: serum or plasma Type: chemiluminescence assay |

IgG | No | NA | 841 | 91.2 | 97.3 | 83 | 20 | 730 | 8 | 81 | 99 |

|

MAGLUMI IgM de 2019-nCoV (CLIA) ANVISA registry number: 80102512431 Samples: serum or plasma Type: chemiluminescence assay |

IgM | No | NA | 289 | 78.6 | 97.5 | 70 | 5 | 195 | 19 | 93 | 91 |

|

One Step COVID-2019 Test; ANVISA registry number: 80537410048 Samples: whole blood (fingertip not reported), serum or plasma Type: immunochromatographic assay |

IgM/IgG | Yes | 15 | 596 | 86.4 | 99.6 | 312 | 1 | 234 | 49 | 100 | 83 |

Ag, antigen; NA, not applicable; FN, false negative; FP, false positive; NPV, negative predictive value; NR, not reported; PPV, positive predictive value; POC, point-of-care; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity.

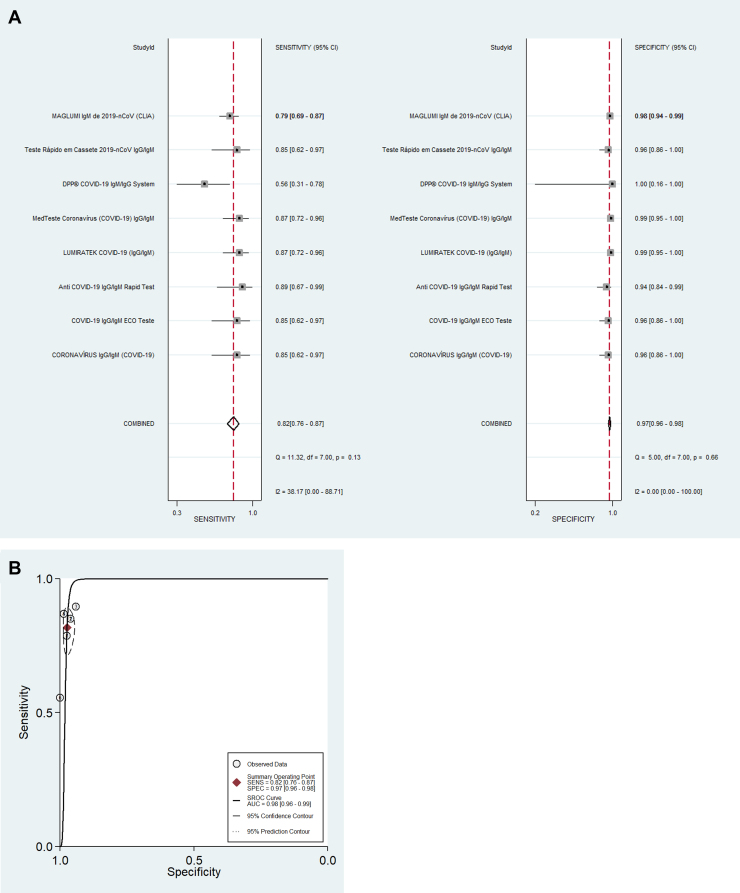

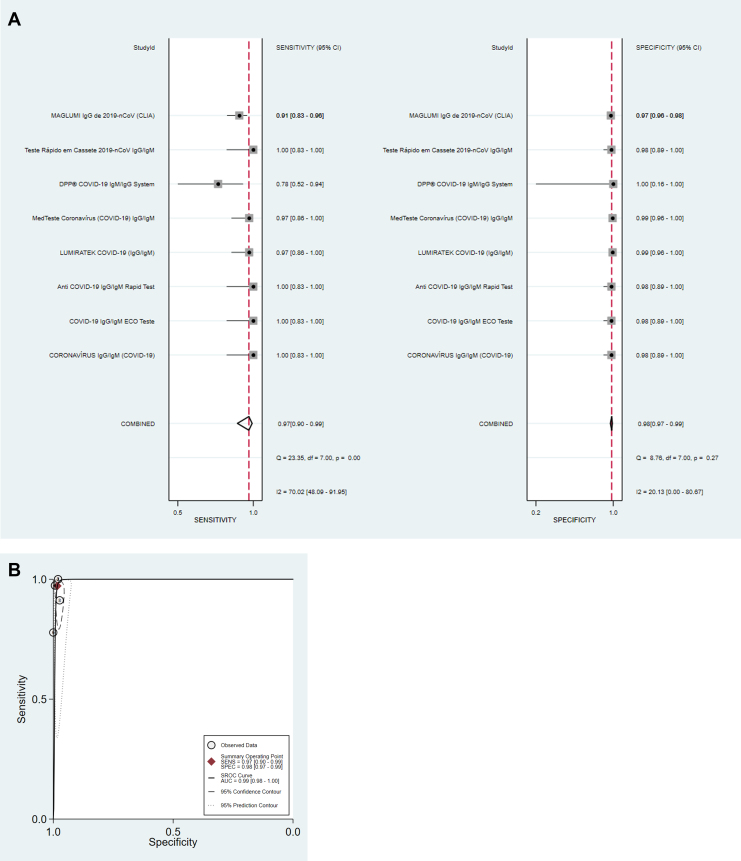

For detection of IgM antibodies (eight tests; 951 samples), pooled diagnostic accuracy measures [95%CI] were: Se = 82% [76–87]; Sp = 97% [96–98]; DOR = 168 [92–305]; LR+ = 31.3 [19.7–49.7]; LR− = 0.19 [0.14–0.25] and SROC = 0.98 [0.96–0.99] (Fig. 1A and B). For detection of IgG antibodies (eight tests; 1503 samples), pooled diagnostic accuracy measures [95%CI] were: Se = 97% [90–99]; Sp = 98% [97–99]; DOR = 1994 [385–10334]; LR+ = 56.6 [30.6–104.7]; LR− = 0.03 [0.01–0.11]; and SROC = 0.99 [0.98–1.00] (Fig. 2A and B). Finally, for detection of SARS-CoV-2 by antigen or molecular assays in nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal swabs (four tests; 464 samples), pooled diagnostic accuracy measures [95%CI] were: Se = 97% [85–99]; Sp = 99% [77–100]; DOR = 2649 [30–233056]; LR+ = 89.5 [3.3–2400.8]; LR− = 0.03 [0.01–0.17]; and SROC = 0.99 [0.98–1.00] (Fig. 3A and B).

Fig. 1.

Pooled diagnostic accuracy analysis (A) and summary receiver operating characteristic curve (B) of tests (n = 8) for detection of IgM antibodies tests against SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 2.

Pooled diagnostic accuracy analysis (A) and summary receiver operating characteristic curve (B) of tests (n = 8) for detection of IgG antibodies tests against SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 3.

Pooled diagnostic accuracy analysis (A) and summary receiver operating characteristic curve (B) of tests (n = 4) using nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal swabs for detection of antigen or nuclei acid of SARS-CoV-2.

This meta-analysis highlighted the accuracy of tests for COVID-19 diagnosis registered by the Brazilian health authorities (ANVISA). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide pooled diagnostic accuracy of tests for COVID-19 available for clinical use in Brazil. Large scale testing is essential to tackle COVID-19 because accurate knowledge of the number of confirmed cases provides information on the spread of the virus within a population and thus on the evolution of the pandemic. As of April 3rd 2020, the Brazilian Ministry of Health had confirmed around 9000 COVID-19 confirmed cases.6 However, the actual number of cases is likely much higher because of limited testing. Furthermore, while we wait for effective vaccines, the knowledge of the extent of immunity in the population after the pandemic ceases depends on accurate diagnostics which will later guide the use of appropriate strategies when facing a potential second wave of COVID-19.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, medical companies and research institutes have been looking for developing and approving tests to detect current viral infection and immunity to SARS-CoV-2.7 The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection involves collecting the correct specimen from the patient at the right time. SARS-CoV-2 detection using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test kits can be considered as the gold-standard for the diagnosis of COVID-19. However, this technique requires certified laboratories, expensive equipment and trained technicians. Rapid tests for detection of specific antibodies of SARS-CoV-2 in blood samples remain a good choice for diagnosing COVID-19. It is estimated that SARS-CoV-2 IgM antibodies can be detected in a blood sample after 3–6 days and IgG antibodies after eight days of symptoms onset.8 Serological assays, detecting IgM/IgG antibodies, are important tests for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 and can help understand the burden and role of asymptomatic infections. The present study showed that 10 serological tests for IgM/IgG antibodies, including nine point-of-care tests, are currently available in Brazil. These tests are simple and can provide rapid confirmation of COVID-19 confirmation while at the same time being limited due to higher rates of false-negative results when collected in the early-phase of symptoms onset. Our study reports that antigen testing and/or molecular assays using nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal specimens had high accuracy for SARS-CoV-2 detection. In China, the rate of SARS-CoV-2 detection was higher in oropharyngeal compared to nasopharyngeal swabs during the COVID-19 outbreak.9 Naso/oropharyngeal tests might miss early infection leading to a strategy of repeated testing since the likelihood of the SARS-CoV-2 being present in the nasopharynx increases with time.8 In the present study, the pooled sensitivity of tests using the detection of COVID-19 IgM antibodies in blood was lower compared to antigen/molecular assay detection in nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs (82% [95%CI 76–87] vs 97% [95%CI 85–99]).

It is worth noting that for this analysis we relied on the accuracy of available tests for COVID-19 as per information provided by the manufacturers during the test registration process at ANVISA. There were no peer-reviewed publications. Moreover, data of clinical significance with regards to the diagnostic validity of each test, such as patients’ characteristics or time of sample collection after the onset of symptoms, were not provided. Literature searches that included test names, dealers, or manufacturers, yielded a single paper that described the analytical performance of a molecular assay to diagnose COVID-19 in nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal specimens.10 Moreover, few tests have been validated with a limited number of samples (≤20), and only half of the tests included more than 150 samples in validation studies. In addition, these tests might present cross-reactivity with other coronavirus that cause respiratory diseases. Among all tests, the One Step COVID-2019 Test is said to have been tested with one of the highest study sample, N = 596. However, the manufacturers did not describe accuracy for IgM and IgG assays separately in the ANVISA document leading to the exclusion of the test from the forest plot. Finally, there were few tests that clearly used similar samples for validation of different tests. Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted Cellex an emergency use authorization to market a rapid antibody test for COVID-19 (Cellex qSARS-CoV-2 IgG/IgM Rapid Test), the first antibody test released during the pandemic (https://www.fda.gov/media/136622/download). Of 128 samples confirmed positive by reverse transcription PCR in premarket testing, 120 tested positive by IgG, IgM, or both. Of 250 confirmed negative, 239 were negative by the rapid test. Moreover, the numbers translated to a positive percent agreement with RT-PCR of 93.8% (95% CI: 88.06–97.26%) and a negative percent agreement of 96.4% (95% CI: 92.26–97.78%), according to labeling (https://www.fda.gov/media/136625/download).

In conclusion, we have reviewed the details and reported on the pooled diagnostic accuracy of different types of tests currently available to tackle COVID-19 in Brazil. A total of 16 tests currently available and registered at the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) were identified, mostly rapid tests to detect IgM and/or IgG antibodies. The pooled diagnostic accuracy of tests available in Brazil was satisfactory, and they can be helpful for emergency testing during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. However, it is important to highlight that the rate of false negative results from tests which detect SARS-CoV-2 IgM antibodies, used for detection of COVID-19 in the acute phase, ranged from 10 to 44%. Furthermore, there is scarce evidence-base validation results published in Brazil. Future studies addressing the diagnostic performance of a panel of tests for COVID-19 in the Brazilian population are urgently needed.

Authors’ contributions

Rodolfo Castro: study concept and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript; Paula M Luz: data collection, interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript; Mayumi D Wakimoto: interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript; Valdilea G Veloso: interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript; Beatriz Grinsztejn: study supervision, interpretation of data and critical revision of the manuscript, Hugo Perazzo: study concept and design, study supervision, data collection, interpretation of data, statistical analysis, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2020.04.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . 2020. Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: increased transmission in the EU/EEA and the UK – sixth update: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/rapid-risk-assessment-novel-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-pandemic-increased. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker P., Whittaker C., Watson O., et al. 2020. The Global Impact of COVID-19 and Strategies for Mitigation and Suppression: Imperial College London. Available from: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-Global-Impact-26-03-2020v2.pdf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salathe M., Althaus C.L., Neher R., et al. COVID-19 epidemic in Switzerland: on the importance of testing, contact tracing and isolation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20225. doi: 10.4414/smw.2020.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imperial College London . 2020. The Global Impact of COVID-19 and Strategies for Mitigation and Suppression. http://www.imperial-college-covid19-global-unmitigated-mitigated-suppression-scenarios.xlsx/ [accessed 30.3.20] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dwamena B. Department of Economics, Boston College; 2007. MIDAS: Stata module for meta-analytical integration of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456880.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.COVID-19 in Brazil: update of confirmed cases and deaths; 2020. https://covid.saude.gov.br/ [accessed 3.4.20].

- 7.Petherick A. Developing antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2020;395:1101–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30788-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z., Yi Y., Luo X., et al. Development and clinical application of a rapid IgM-IgG combined antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25727. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang W., Xu Y., Gao R., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfefferle S., Reucher S., Norz D., Lutgehetmann M. Evaluation of a quantitative RT-PCR assay for the detection of the emerging coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 using a high throughput system. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000152. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.9.2000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.