Editor—Patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may present to hospitals and emergency medical services with an atypical form of acute respiratory distress syndrome.1 Although anecdotal, a common clinical pattern has emerged, with a remarkable discrepancy between relatively well preserved lung compliance and a severely compromised pulmonary gas exchange, leading to grave hypoxaemia yet without proportional signs of respiratory distress. The compensatory ventilatory response to hypoxaemia, increased minute ventilation, may lead to extreme hypocapnia. Carbon dioxide (CO2) diffuses through tissues about 20 times more rapidly than does oxygen (O2), and these properties likely underlie the disproportional pulmonary exchange of CO2 and O2 in these patients. The pathoanatomical and pathophysiological basis for respiratory failure in COVID-19 is yet undetermined, but diffuse alveolar damage with interstitial thickening leading to compromised gas exchange is a plausible mechanism.2 Varying degrees of atelectasis and consolidation likely contribute.

Experiments in hypobaric chambers have revealed that hypocapnic hypoxia is not usually accompanied by air hunger; instead, a paradoxical feeling of calm and well-being may result. This phenomenon has been coined ‘silent hypoxia’. End-tidal CO2 values in the 1.4–2.0 kPa range have been reported in COVID-19 patients, but apart from a rapid respiratory rate the clinical presentation in these patients can be misleading. We have observed patients with extreme hypoxaemia showing little distress; rather they tend to be impassive, cooperative, and haemodynamically stable. However, sudden and rapid respiratory decompensation may occur. This particular clinical presentation in COVID-19 patients contrasts with our previous experience with critically ill patients in respiratory failure, in which patients with decompensated heart failure, sepsis, or massive pulmonary embolism tend to present with air hunger, dyspnoea, distress, arterial hypotension, and isocapnic or hypercapnic hypoxia.

The physiological hallmarks of hypocapnic hypoxia have been studied extensively in aviation medicine.3 Decompression to high altitude causes severe hypoxaemia, which triggers the carotid chemoreceptors and sparks a brisk respiratory response with ensuing hypocapnia. The respiratory alkalosis shifts the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve to the left, thereby increasing haemoglobin's oxygen affinity, evident from a decrease in the P50 value and an increase in arterial oxygen saturation ().4 In addition, the alveolar gas equation predicts that decreased alveolar CO2 tension () will result in a corresponding increase in alveolar oxygen tension (). Combined, these two mechanisms will increase in hypocapnic hypoxia compared with an isocapnic or hypercapnic hypoxic state. We speculate that most clinicians' intuitive understanding of the effect size produced by these mechanisms for a given change in may be limited.

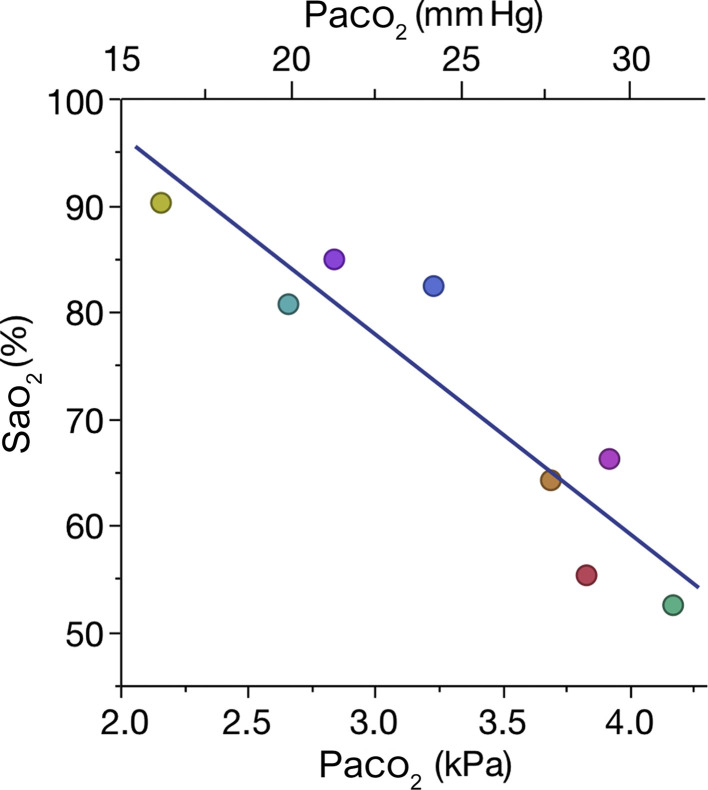

The effects of hypocapnia on can be illustrated with data from a recent hypobaric chamber experiment. In a simulated high-altitude parachute jump from 30 000 ft, nine volunteers from the Norwegian Special Operations Command underwent repeated blood gas testing while breathing air at different ambient pressures.5 Despite values of 3.3 (2.9–3.7) kPa (median [range]), eight out of nine participants showed no signs of respiratory distress and were cooperative and alert with stable haemodynamics. Interestingly, a wide range of values across individuals were found for any given inspiratory oxygen pressure. At ambient pressure 42.1 kPa, corresponding to a pressure altitude of approximately 22 000 ft, values ranged from 52% to 90%, with corresponding values of of 2.16–4.17 kPa and of 3.22–5.61 kPa. One individual achieved of 90% with of 5.6 kPa and of 2.16 kPa, illustrating how a relatively high value can be found despite a very low . Linear regression analysis (Fig 1 ) estimates the effect size of hyperventilation, that is how at one given inspiratory P o 2 a change in affects . Such visualisation can contribute to a better understanding of how substantially a left shift in the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve changes .

Fig 1.

Relation between arterial oxygen saturations () and arterial partial pressures of carbon dioxide () in eight volunteers breathing air in a hypobaric chamber at ambient pressure 42.1 kPa, corresponding to a pressure altitude of ∼22 000 ft.5 Inspiratory oxygen pressure is 7.5 kPa. The model predicts that an increase in from 2.5 to 4.5 kPa would decrease from 87% to 50%. R2=0.88, P<0.001.

Extreme hypocapnic hypoxia in patients with respiratory failure has previously been relatively unusual; therefore, this presentation challenges our intuitive thinking and clinical pattern recognition. The physiology of hypocapnic hypoxia has implications for how we interpret physiological parameters. Instinctively, we judge an value of 93% as fair. However, without knowledge of the accompanying value, it is impossible to infer from the degree of hypoxaemia and consequently the severity of the respiratory failure.

COVID-19 patients have a median reported duration from illness onset to ICU admission of 12 days,1 and they can deteriorate quickly. Ensuring timely hospital admission can therefore be challenging. These patients are evaluated by general practitioners, often by telephone because of quarantine rules, or by paramedics or emergency physicians in a pre-hospital context. To assess the risk of imminent respiratory failure, clinical evaluation should give emphasis to respiratory rate, work of breathing, use of accessory musculature, and skin perfusion. Pulse oximetry readings should be interpreted in the light of values or while acknowledging the absence of this important information. Although arterial–alveolar difference in increases during low cardiac output states and increased dead space ventilation, end-tidal CO2 values have been reported to correlate well with in non-intubated patients, especially during hypocapnia.6 End-tidal CO2 can be easily measured in a pre-hospital setting.

In COVID-19 patients, a low end-tidal CO2 should alert the physician that respiratory failure is evolving and that decompensation might be imminent. If ventilatory support is instituted, anaesthesiologists, emergency physicians, and intensivists should be aware of the need to sustain a high ventilatory minute volume. In the case of intubation, one should consider the danger of apnoea during induction of anaesthesia. In marginal patients with severe hypocapnic hypoxia, an increase in will lead to a right shift of the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve, resulting in an abrupt fall in and a risk of circulatory collapse.

The clinical presentation and pathophysiology of the COVID-19 patient challenges our notion of how respiratory failure in critically ill patients unfolds. We must adapt to a constantly changing situation with a rapidly expanding evidence base. Awaiting reliable data, we have to integrate experience with our understanding of physiology to make rational clinical decisions.

Declarations of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This article is accompanied by an editorial: Using applied lung physiology to understand COVID-19 patterns by Komorowski & Aberegg, Br J Anaesth 2020:125:250–253, doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.05.019

References

- 1.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tian S., Hu W., Niu L., Liu H., Xu H., Xiao S.-Y. Pulmonary pathology of early-phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol Adv. 2020;15:700–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010. Access Published February 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westendorp R.G., Blauw G.J., Frölich M., Simons R. Hypoxic syncope. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1997;68:410–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton C., Steinlechner B., Gruber E., Simon P., Wollenek G. The oxygen dissociation curve: quantifying the shift. Perfusion. 2004;19:141–144. doi: 10.1191/0267659104pf734oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottestad W., Hansen T.A., Pradhan G., Stepanek J., Høiseth L.Ø., Kåsin J.I. Acute hypoxia in a simulated high-altitude airdrop scenario due to oxygen system failure. J Appl Physiol. 2017;123:1443–1450. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00169.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barton C.W., Wang E.S.J. Correlation of end-tidal CO2 measurements to arterial PaCO2 in nonintubated patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:560–563. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]