Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the recurrence rate of Helicobacter pylori infection after eradication in Jiangjin District, Chongqing, China, and to analyze the related causes.

Methods

Outpatients who were eradicated of H. pylori infection with standard therapy between August 2014 and August 2017 were included in this study. The recurrence rate was investigated 1 year later. Data regarding gender, smoking, alcohol intake, frequency of eating out, and treatment strategy were recorded, and their relationships with the recurrence rate were analyzed. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the independent risk factors for H. pylori infection recurrence.

Results

In total, 400 patients (225 males and 175 females) were included in this study. Of them, the recurrence rate of H. pylori infection was 4.75% (19/400), with 5.33% (12/225) in males and 4.57% (7/175) in females, showing no gender difference. The recurrence rate was 7.03% (9/128) in smokers and 3.68% (10/272) in nonsmokers, while it was 6.45% (12/186) in those who drink alcohol and 3.27% (7/214) in those who do not drink alcohol, showing no significant differences. The higher the frequency of eating out, the higher the recurrence rate of H. pylori infection (P = 0.001). There was a statistically significant difference in the recurrence rate between patients receiving treatment alone and patients whose family members also received treatment (6.08% vs. 0.96%, P = 0.035). Drinking and dining out were independent risk factors for H. pylori infection recurrence (P = 0.014 for drinkers and P = 0.015 and P = 0.003 for those who sometimes and often dine out, respectively).

Conclusions

The overall recurrence rate after H. pylori eradication by standard therapy in Jiangjin District is 4.75%. Reducing the frequency of eating out and family members receiving treatment may reduce the recurrence of H. pylori infection.

1. Introduction

Chronic gastritis is one of the most common life-long inflammatory diseases. More than half of the world's population are estimated to have chronic gastritis to some extent [1]. Helicobacter pylori infection is one major cause of chronic gastritis. About 20% of H. pylori-infected patients develop peptic ulcers, and 1% of infected patients develop gastric malignancies, including gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [2–4]. In addition, H. pylori is thought to be associated with some extragastric disorders, such as cardiovascular, skin, and blood system diseases [3, 4].

The prevalence of H. pylori infection varies greatly geographically. In developing countries, it is estimated that more than 80% of the population is H. pylori positive, even in children and adolescents, while in developed countries, less than 40% of the population is H. pylori positive, and children have a lower rate of infection than adults and the elderly [5]. Since H. pylori infection is very common and leads to many diseases, both domestic and international guidelines recommend eradication therapy for H. pylori-infected patients [6–8]. However, studies have shown that despite regular treatment, there is still a risk of H. pylori recurrence [9–11], with a higher rate in developing countries than in developed countries. H. pylori recurrence is defined as negative detection of H. pylori at 4 weeks after eradication therapy but positive detection at some later time [12]. H. pylori recurrence can occur either by recrudescence or reinfection. Recrudescence refers to the recolonization of the same strain, while reinfection refers to colonization with a new strain [9, 10]. Most cases of H. pylori recurrence are due to recrudescence.

Many risk factors for H. pylori infection have been reported, including socioeconomic factors, education, family density, lifestyle, and other factors [13–16]. These factors are also possible risk factors for H. pylori recurrence, since reinfection is one form of recurrence. A meta-analysis has shown that H. pylori recurrence rates are significantly and inversely correlated with socioeconomic development metrics [17].

H. pylori recurrence after eradication will reduce the clinical significance of eradication of H. pylori, inevitably increase the difficulty of drug selection, and aggravate H. pylori resistance [9, 18]. The H. pylori infection rate is 54.59% in western Chongqing [19], which is a high-prevalence area with many patients, but the recurrence rate of H. pylori infection remains unclear. This study was aimed at investigating the recurrence rate of H. pylori infection after eradication in patients living in Jiangjin District, Chongqing, China, and at examining the related factors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

From August 2014 to August 2017, outpatients with H. pylori infection confirmed by the 14C-urea breath test from Jiangjin District, Chongqing, China, were enrolled in this study. The outpatients received a quadruple treatment regimen to eradicate H. pylori: rabeprazole capsules (10 mg bid), amoxicillin (1 g bid), clarithromycin (0.5 g bid), and pectin bismuth (300 mg bid), for 14 days. If a family member was confirmed to be infected as well, the same treatment was given to the family member. One month after the end of treatment, the subjects who were H. pylori negative, as confirmed by the 14C-urea breath test, were included in this study. The eradication was confirmed according to the Fifth National Consensus Opinion on the Diagnosis and Treatment of H. pylori [6].

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age between 18 and 65 years; not a recurrent patient; no use of proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists, expectorants, or antibiotics within 4 weeks; no related drug allergy history; no gastrointestinal bleeding, pyloric obstruction, perforation, or other complications; no history of digestive tract surgery; and no serious heart, lung, liver, or kidney dysfunction. Exclusion criteria were patients with severe gastric epithelial dysplasia, a pathological diagnosis of malignancy, or lactating or pregnant women.

The protocol of this prospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangjin Central Hospital of Chongqing. All patients with H. pylori infection, as confirmed by the 14C-urea breath test, were enrolled after informed consent.

2.2. Data Collection

Gender, smoking history, drinking history, and frequency of eating out (seldom, <1 per month; sometimes, <1 per week and >1 per month; and often, >1 per week) were recorded. One year later, the recurrence of H. pylori infection was measured by the 14C-urea breath test.

2.3. Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 17.0 software. Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The count data are expressed as a percentage. Comparisons between two groups were performed using the t test or χ2 test. Variants with a P value < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the independent risk factors for H. pylori infection recurrence. The difference was considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Participants

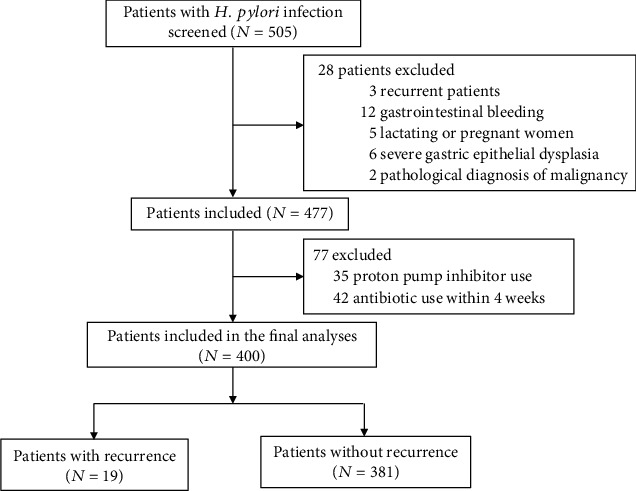

The flow chart of the present study is presented in Figure 1, and the baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. In total, 400 patients (225 males and 175 females) aged 18–65 years were included. Among them, 19 (4.75%) patients tested positive for H. pylori infection at 1 year after eradication. The recurrence rate was 5.33% (12/225) in males and 4.57% (7/175) in females, with no statistical difference (χ2 = 0.387, P = 0.534).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the present study.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the participants.

| Total patients (N = 400) | Patients with recurrence (N = 19) | Patients without recurrence (N = 381) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 37.8 ± 12.5 | 39.23 ± 15.3 | 34.36 ± 14.6 | 0.653 |

| Sex (male/female) | 225/175 | 12/7 | 213/168 | 0.534 |

3.2. Relationship between Recurrence Rate and Smoking

Of all 400 H. pylori-eradicated patients, 128 were smokers and 272 were nonsmokers. The recurrence rate was 7.03% (9/128) in smokers and 3.68% (10/262) in nonsmokers, with no statistical difference (χ2 = 1.947, P = 0.163; Table 2).

Table 2.

Recurrence of H. pylori infection in smokers and nonsmokers.

| Group | Number of patients with recurrence | Number of patients without recurrence | Total patients | Recurrence rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smokers | 9 | 119 | 128 | 7.03% |

| Nonsmokers | 10 | 262 | 272 | 3.68% |

| χ 2 | 1.947 | |||

| P | 0.163 |

3.3. Relationship between Recurrence Rate and Drinking Alcohol

Of all 400 H. pylori-eradicated patients, 186 drank alcohol and 214 did not drink alcohol. The recurrence rate was 6.45% (12/186) in drinkers and 3.27% (7/207) in nondrinkers, with no statistical difference (χ2 = 2.019, P = 0.155; Table 3).

Table 3.

Recurrence of H. pylori infection in drinkers and nondrinkers.

| Group | Number of patients with recurrence | Number of patients without recurrence | Total patients | Recurrence rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinkers | 12 | 174 | 186 | 6.45% |

| Nondrinkers | 7 | 207 | 214 | 3.27% |

| χ 2 | 2.019 | |||

| P | 0.155 |

3.4. Relationship between Recurrence Rate and Frequency of Dining Out

Of all 400 H. pylori-eradicated patients, 159 patients seldom ate outside the home, 137 sometimes ate out, and 104 often ate out. The recurrence rate was 0.63% (1/159) in the seldom ate out group, 2.92% (4/137) in the sometimes ate out group, and 13.46% (14/104) in the often ate out group (χ2 = 13.739, P = 0.001; Table 4). The recurrence rate was significantly higher in the often ate out group than in the other two groups.

Table 4.

Recurrence of H. pylori infection in patients with different frequencies of dining out.

| Frequency of dining out | Number of patients with recurrence | Number of patients without recurrence | Total patients | Recurrence rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seldom | 1 | 158 | 159 | 0.63% |

| Sometimes | 4 | 133 | 137 | 2.92% |

| Often | 14 | 90 | 104 | 13.46% |

| χ 2 | 13.739 | |||

| P | 0.001 |

3.5. Relationship between Recurrence Rate and Treatment of Infected Family Members

Of all H. pylori-eradicated patients, 104 had H. pylori-infected family members who were treated and 296 did not have infected family members or the infection status of their family members was unknown. The recurrence rate was 0.96% (1/104) in those with H. pylori-infected family members who were treated and 6.08% (18/296) in those without H. pylori-infected family members or the infection status of their family members was unknown, showing a significant difference (χ2 = 4.458, P = 0.035; Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of the treatment strategy on the recurrence of H. pylori infection.

| Treatment strategy | Number of patients with recurrence | Number of patients without recurrence | Total patients | Recurrence rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment alone | 18 | 278 | 296 | 6.08% |

| Cotherapy | 1 | 103 | 104 | 0.96% |

| χ 2 | 4.458 | |||

| P | 0.035 |

3.6. Drinking and Dining Out Were Independent Risk Factors for H. pylori Infection Recurrence

Next, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the independent risk factors for H. pylori infection recurrence. The results showed that drinking and dining out were independent risk factors for H. pylori infection recurrence (P = 0.014 for drinkers and P = 0.015 and P = 0.003 for those who sometimes and often dine out, respectively; Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis for independent risk factors for H. pylori infection recurrence.

| Variants | P value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper | Lower | |||

| Smoker | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.086 | 2.425 | 0.882 | 6.666 |

| Drinker | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.014 | 3.711 | 1.303 | 10.568 |

| Frequency of dining out | ||||

| Seldom | Reference | |||

| Sometimes | 0.015 | 35.665 | 1.981 | 642.005 |

| Often | 0.003 | 6.45 | 1.926 | 21.6 |

| Treatment strategy | ||||

| Alone | Reference | |||

| Cotherapy | 0.861 | 1.298 | 0.069 | 24.381 |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the recurrence rate of H. pylori infection after eradication in Jiangjin District, Chongqing, China. Our data showed that the recurrence rate was 4.75%. There was no statistical difference in terms of gender, smoking history, or drinking history, while there were statistical differences between those who frequently ate out compared to those who did not as well as between those whose family members were treated and those who did not have treated family members. Multivariate logistic regression showed that drinking and dining out were independent risk factors for H. pylori infection recurrence.

There are two ways that H. pylori infection reoccurs after eradication in the stomach [20]. One is recrudescence, which is caused by possible residual strains that multiply, including H. pylori that is not completely removed by the treatment. This occurs when the sensitivity of H. pylori detection methods is too low, there is a high false-negative rate, or changes occur in the H. pylori morphology. Sometimes, the spiral bacteria may transform into spherical bacteria when the environment is poor, and then they return to the spiral form when the environment is suitable, thus causing disease [21]. The other way that H. pylori infection reoccurs is reinfection of new strains, including H. pylori in oral repositories. These new strains may cause H. pylori recurrence when the bacteria move from the mouth into the stomach. Reinfection may also occur due to close contact between people or to exposure to a common source of infection [20].

The recurrence rate of H. pylori varies from place to place and is related to the local socioeconomic level [9]. The lower the economic rate, the higher the recurrence rate. For example, the 1-year recurrence rate in Latin America is as high as 11.5%, while the 1-year recurrence rate in Morocco is only 0.45% [18, 22]. The present study found that the recurrence rate of H. pylori infection after eradication in Jiangjin District was 4.75%, which is a little higher than the international average (4.3%) [9, 23]. The annual recurrence rate of H. pylori infection after eradication is reported to be 1.08–1.75% in China [24, 25]. In addition, a meta-analysis has revealed that the pooled H. pylori recurrence rate in China is 2.2% (95% CI: 0.8–4%) [9]. The recurrence rate in the present study was a little higher than that reported previously, which may be caused by many factors, such as location, economic level, scheme selection, drug compliance, and detection method. The latest multicenter prospective study has suggested that ethnic groups, education level, family history, and residence location are independent risk factors for H. pylori recurrence [26]. The authors found that the recurrence rate of the residence located in Western China was significantly higher than that of other places, which may partially explain the high recurrence rate of H. pylori infection in the present study, since Chongqing is a western city in China. Of note, the recurrence rate for males was slightly higher than that for females, although the difference is not significant.

There are many risk factors for H. pylori infection, including socioeconomic factors, education, family density, lifestyle, and other factors [13–16]. Some studies have suggested that smoking and drinking alcohol can reduce the H. pylori infection rate [27–29], while other studies show that smoking has no relationship with H. pylori infection [30–32]. This study showed that smoking and drinking do not lead to an increase in the recurrence of H. pylori infection. However, multivariate logistic regression revealed that drinking was an independent risk factor for H. pylori infection recurrence. A study by Amini et al. [33] has demonstrated that the long-term use of common tableware can lead to a high incidence of H. pylori infection, indicating that changing dietary habits may limit the spread of H. pylori infection. Our study showed that patients who ate out often had a significantly higher recurrence rate of H. pylori infection than those who ate out sometimes or rarely. Moreover, multivariate logistic regression indicated that dining out was an independent risk factor for H. pylori infection recurrence. This may be because frequent diners have a higher exposure to the source of infection.

H. pylori infection has the characteristics of intrafamily transmission. When the infection is successfully eradicated from a patient, he will become reinfected by the same H. pylori strain [34] carried by the spouse. Simultaneous treatment of H. pylori-infected patients in the same family will significantly improve the eradication rate [35, 36]. This study also confirmed that the recurrence rate in patients whose H. pylori-infected relatives living with them also received treatment was significantly lower than that of patients receiving treatment alone. Our results indicate that H. pylori infection showed family aggregation, which may be related to close contact, having the same living and eating habits, and exposure to common sources of infection. The cotherapy of family members can improve the therapeutic effect.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our data showed that the recurrence rate of H. pylori infection in Jiangjin District, China, is generally low and not related to gender, smoking, or drinking; however, the recurrence rate is related to the frequency of eating out and the family treatment strategy. Furthermore, drinking and dining out were independent risk factors for H. pylori infection recurrence. Our study suggests that the rate of recurrence of H. pylori infection may be reduced by limiting the frequency of eating out and receiving cotreatment with family members. Due to the small number of cases included in this study and the short follow-up period, a multicenter, large-scale, randomized controlled trial is needed to confirm our conclusion.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Medical Science Research of Chongqing Health and Family Planning Commission (No. 2016MSXM162).

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sipponen P., Maaroos H. I. Chronic gastritis. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2015;50(6):657–667. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1019918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suerbaum S., Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(15):1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki H., Marshall B. J., Hibi T. Overview: Helicobacter pylori and extragastric disease. International Journal of Hematology. 2006;84(4):291–300. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y., Du T., Chen X., Yu X., Tu L., Zhang C. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and overweight or obesity in a Chinese population. Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2015;9(9):945–953. doi: 10.3855/jidc.6035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kusters J. G., van Vliet A. H. M., Kuipers E. J. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2006;19(3):449–490. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00054-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chinese Society of G, Chinese Study Group on Helicobacter p, Peptic U., et al. Fifth Chinese national consensus report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2017;56:532–545. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugano K., Tack J., Kuipers E. J., et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64(9):1353–1367. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malfertheiner P., Megraud F., O'Morain C. A., et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2016;66(1):6–30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu Y., Wan J. H., Li X. Y., Zhu Y., Graham D. Y., Lu N. H. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the global recurrence rate of Helicobacter pylori. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2017;46(9):773–779. doi: 10.1111/apt.14319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niv Y., Hazazi R. Helicobacter pylori recurrence in developed and developing countries: meta-analysis of 13C-urea breath test follow-up after eradication. Helicobacter. 2008;13(1):56–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S. Y., Hyun J. J., Jung S. W., Koo J. S., Yim H. J., Lee S. W. Helicobacter pylori recurrence after first- and second-line eradication therapy in Korea: the problem of recrudescence or reinfection. Helicobacter. 2014;19(3):202–206. doi: 10.1111/hel.12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fallone C. A., Chiba N., van Zanten S. V., et al. The Toronto consensus for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in adults. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(1):51–69.e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch A., Krause T. G., Krogfelt K., Olsen O. R., Fischer T. K., Melbye M. Seroprevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in Greenlanders. Helicobacter. 2005;10(5):433–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown L. M. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2000;22(2):283–297. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim S. H., Kwon J. W., Kim N., et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterology. 2013;13(1):p. 104. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung W. K., Ng E. K. W., Lam C. C. H., et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in 1st degree relatives of Chinese gastric cancer patients. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006;41(3):274–279. doi: 10.1080/00365520510024269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan T. L., Hu Q. D., Zhang Q., Li Y. M., Liang T. B. National rates of Helicobacter pylori recurrence are significantly and inversely correlated with human development index. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2013;37(10):963–968. doi: 10.1111/apt.12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benajah D. A., Lahbabi M., Alaoui S., et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and its recurrence after successful eradication in a developing nation (Morocco) Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology. 2013;37(5):519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou G. Epidemiological investigation and drug resistance status of Helicobacter pylori in western Chongqing. China Pharmaceuticals. 2018;27:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Ende A., van der Hulst R. W. M., Dankert J., Tytgat G. N. J. Reinfection versus recrudescence in Helicobacter pylori infection. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1997;11(Supplement 1):55–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.11.s1.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fei Y. Spherical transformation of Helicobacter pylori in water and its pathogenicity. Chinese Journal of Microbiology and Immunology. 2001;21:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan D. R., Torres J., Sexton R., et al. Risk of recurrent Helicobacter pylori infection 1 year after initial eradication therapy in 7 Latin American communities. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(6):578–586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burucoa C., Axon A. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2017;22, article e12403(Supplement 1) doi: 10.1111/hel.12403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell H. M., Hu P., Chi Y., Chen M. H., Li Y. Y., Hazell S. L. A low rate of reinfection following effective therapy against Helicobacter pylori in a developing nation (China) Gastroenterology. 1998;114(2):256–261. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou L. Y., Song Z. Q., Xue Y., Li X., Li Y. Q., Qian J. M. Recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection and the affecting factors: a follow-up study. Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2017;18(1):47–55. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie Y., Song C., Cheng H., et al. Long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori reinfection and its risk factors after initial eradication: a large-scale multicentre, prospective open cohort, observational study. Emerging Microbes & Infections. 2020;9(1):548–557. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1737579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogihara A., Kikuchi S., Hasegawa A., et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and smoking and drinking habits. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2000;15(3):271–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozaydin N., Turkyilmaz S. A., Cali S. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori in Turkey: a nationally-representative, cross-sectional, screening with the 13C-Urea breath test. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1, article 1215) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu S. Y., Han X. C., Sun J., Chen G. X., Zhou X. Y., Zhang G. X. Alcohol intake and Helicobacter pylori infection: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Infectious Diseases. 2016;48(4):303–309. doi: 10.3109/23744235.2015.1113556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gikas A., Triantafillidis J. K., Apostolidis N., Mallas E., Peros G., Androulakis G. Relationship of smoking and coffee and alcohol consumption with seroconversion to Helicobacter pylori: a longitudinal study in hospital workers. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004;19(8):927–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brenner H., Rothenbacher D., Bode G., Adler G. Relation of smoking and alcohol and coffee consumption to active Helicobacter pylori infection: cross sectional study. BMJ. 1997;315(7121):1489–1492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7121.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferro A., Morais S., Rota M., et al. Tobacco smoking and gastric cancer: meta-analyses of published data versus pooled analyses of individual participant data (StoP Project) European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2018;27(3):197–204. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amini M., Karbasi A., Khedmat H. Evaluation of eating habits in dyspeptic patients with or without Helicobacter pylori infection. Tropical Gastroenterology. 2009;30(3):142–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas E., Jiang C., Chi D. S., Li C., Ferguson D. A., Jr. The role of the oral cavity in Helicobacter pylori infection. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 1997;92(12):2148–2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan Y., Xu Y. Y., Xue F. B., Fan D. M. Meta-analysis on Helicobacter pylori infection between sex and in family assembles. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2003;24(1):54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X., Ou B., Shang S., et al. Correlation between aggregation and eradication therapy in children with Helicobacter pylori infection. Chinese Journal of Practical Pediatrics. 2003;18:475–477. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.