SUMMARY

LRRTM4 is a trans-synaptic adhesion protein regulating glutamatergic synapse assembly on dendrites of central neurons. In the mouse retina, we find that LRRTM4 is enriched at GABAergic synapses on axon terminals of rod bipolar cells (RBCs). Knockout of LRRTM4 reduces RBC axonal GABAA and GABAC receptor clustering and disrupts presynaptic inhibition onto RBC terminals. LRRTM4 removal also perturbs the stereotyped output synapse arrangement at RBC terminals. Synaptic ribbons are normally apposed to two distinct postsynaptic ‘dyad’ partners, but in the absence of LRRTM4 ‘monad’ and ‘triad’ arrangements are also formed. RBCs from retinas deficient in GABA release also demonstrate dyad mis-arrangements but maintain LRRTM4 expression, suggesting that defects in dyad organization in the LRRTM4 knockout could originate from reduced GABA receptor function. LRRTM4 is thus a key synapse organizing molecule at RBC terminals, where it regulates function of GABAergic synapses and assembly of RBC synaptic dyads.

Keywords: synaptic adhesion protein, LRRTM, retina, presynaptic inhibition, ribbon synapse

eTOC blurb:

Sinha et al. show that the trans-synaptic adhesion protein LRRTM4 regulates assembly and function of GABAergic synapses on retinal rod bipolar axons. Impaired GABAergic input onto rod bipolar axons also disrupts arrangement of ribbon sites at specialized two-partner dyad synapses.

INTRODUCTION

Efficient information transfer in the CNS relies on precise partnerships between trans-synaptic adhesion proteins, which regulate multiple aspects of synaptic development and function (Dalva et al., 2007; Sudhof, 2018; Yamagata et al., 2003). Largely, distinct synapse organizing molecules have been found at excitatory and inhibitory synapses of the CNS, underscoring a synapse-type-specific role (Dabrowski et al., 2015; Krueger et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2012; Terauchi et al., 2010; Yim et al., 2013). In general, molecular organizers involved in the assembly and function of excitatory synapses have been more exhaustively characterized compared to inhibitory synapses. Here, we show that a synaptic adhesion molecule essential for formation and function of excitatory synapses also plays an important role at inhibitory synapses, contrary to the expectation that specific trans-synaptic adhesion proteins act either at excitatory or inhibitory synapses.

Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane neuronal proteins or LRRTMs are important for development of excitatory synapses in hippocampal, cortical and thalamic circuits of the CNS (de Wit et al., 2013; de Wit et al., 2009; Ko et al., 2009; Linhoff et al., 2009; Monavarfeshani et al., 2018; Siddiqui et al., 2010; Siddiqui et al., 2013; Soler-Llavina et al., 2011; Takashima et al., 2011). Postsynaptically-localized LRRTMs are a family of adhesion molecules with four known members that interact with neurexins (LRRTM1,2; de Wit et al., 2009; Ko et al., 2009; Siddiqui et al., 2010; Yamagata et al., 2018) or with heparan sulfate proteoglycans, possibly including glypican-4 (LRRTM3,4; de Wit et al., 2013; Ko et al., 2015; Siddiqui et al., 2013) expressed by the presynaptic cell. LRRTM4 in particular regulates the development and strength of glutamatergic (AMPA receptor-driven) synapses on dentate gyrus granule cells of the hippocampus (Siddiqui et al., 2013) and L2/3 cortical neurons (de Wit et al., 2013).

Recent gene-profiling work suggests that LRRTM4 is expressed in the retina, in particular, in the rod bipolar cell (RBC), that is central to the dim-light visual pathway (Shekhar et al., 2016; Woods et al., 2018). RBCs receive synaptic input from rod photoreceptors, and recent studies (Cao et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017) have shown that another leucine rich repeat protein, ELFN1, mediates glutamatergic contacts between rods and RBCs. RBCs provide excitatory, glutamatergic input to two postsynaptic targets (a glycinergic AII and a GABAergic A17 amacrine interneuron) at stereotyped ‘dyad’ ribbon synapses (Fig 1A and see Hoon et al., 2014; Wassle, 2004). The A17 amacrine, makes inhibitory reciprocal synapses onto the same RBC axon from which it receives input (Fig 1A, and see Grimes et al., 2010; Hoon et al., 2014; Wassle, 2004). This presynaptic inhibition, operating via GABAA and GABAC receptors (Fletcher et al., 1998; Grimes et al., 2015; Koulen et al., 1998), regulates glutamate release from RBC terminals (Eggers and Lukasiewicz, 2006; Eggers et al., 2007; Grimes et al., 2015). Given that RBCs lack AMPA receptors, we wondered how LRRTM4 may function at RBC synapses. Using light and serial electron microscopy together with electrophysiology, we discovered an unexpected role of LRRTM4 for the organization of inhibitory synapses mediating presynaptic inhibition and for the assembly of RBC ribbon synapses.

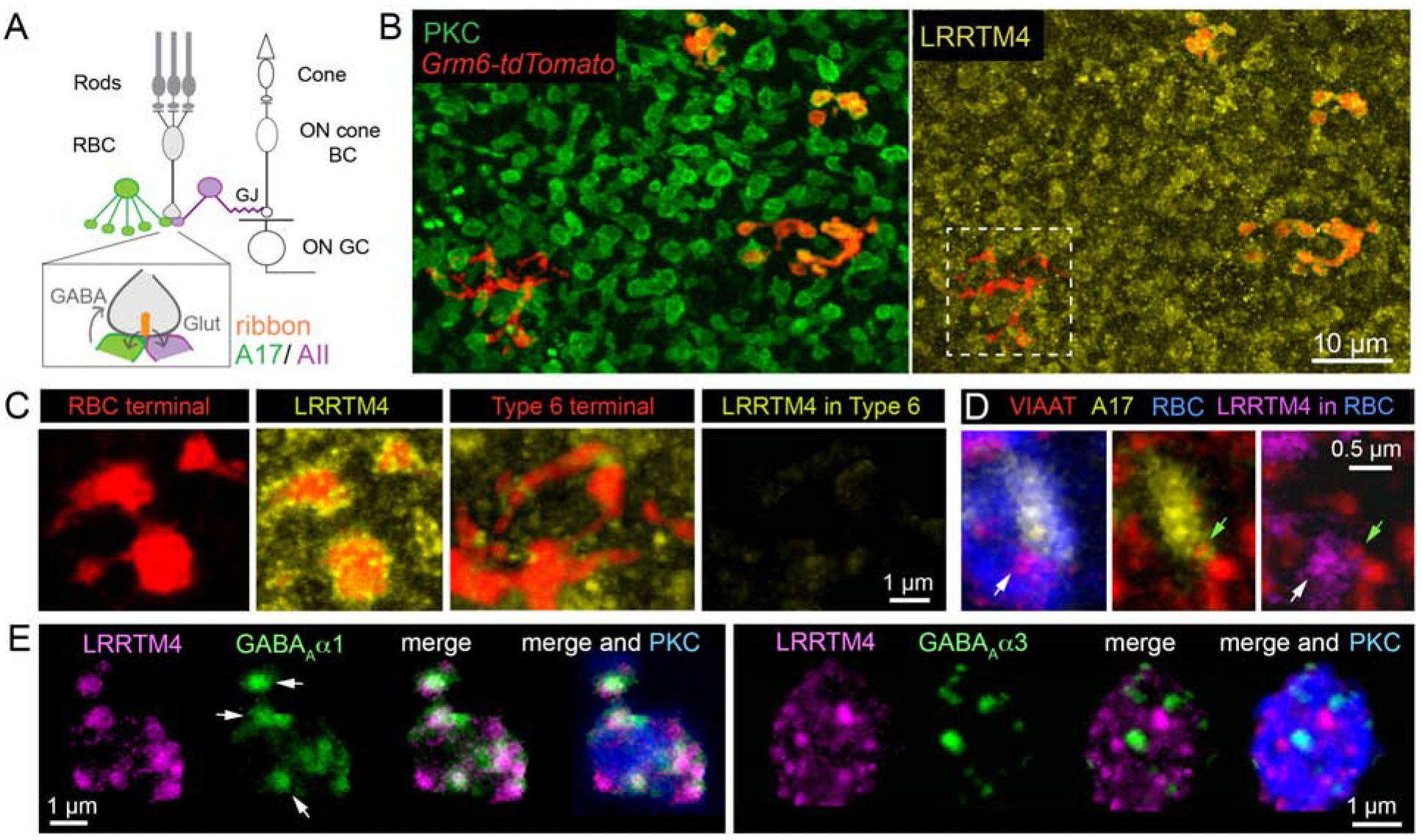

Figure 1: LRRTM4 localizes to GABAergic synapses at mouse retinal rod bipolar axon terminals.

(A) Schematic of retinal pathways. Rod and cone photoreceptors relay light-evoked signals to rod and cone bipolar cells, respectively. Cone photoreceptors synapse onto cone bipolar cells (cone BCs), which connect to retinal output neurons, the ganglion cells (GCs). Rod bipolar cells (RBCs) make glutamatergic (Glut) ribbon synapses onto AII and A17 amacrine interneurons. GABAergic A17 amacrine provide feedback inhibition onto the RBC terminals from which they receive excitatory input. AII glycinergic amacrines form gap-junctions (GJ) with depolarizing (ON) cone BCs thus relaying rod signals to the GCs. (B) En face images show LRRTM4 immunofluorescence selectively localized at protein kinase C (PKC)-positive RBC terminals and not at Type 6 ON cone BC terminals (white box). RBCs and ON cone BCs both express tdtomato in the Grm6-tdtomato transgenic line. (C) Higher magnification view of RBC and Type 6 BC terminals with LRRTM4 immunolabeling. (D) LRRTM4 at RBC terminals (white arrow) is apposed to a VIAAT-immunopositive (green arrow) A17 bouton. (E) LRRTM4 within PKC positive RBC boutons colocalizes with GABAAα1 receptor puncta (arrows, Left panel), but not with GABAAα3 receptor puncta (Right panel).

RESULTS

LRRTM4 is associated with GABAergic feedback synapses on RBC axons.

We used an LRRTM4-specific antibody (Siddiqui et al., 2013) to determine its distribution in the mouse retina. We were particularly interested in RBCs because they show enrichment of both LRRTM4 mRNA (Shekhar et al., 2016; Woods et al., 2018) and protein (Woods et al., 2018). We immunolabeled LRRTM4 and the RBC-specific protein kinase C (PKC) in retinas from Grm6-tdtomato mice (Kerschensteiner et al., 2009) in which RBCs and ON cone bipolar cells (CBCs) are labeled (Fig 1B). LRRTM4 immunoreactivity associated with RBC and ON CBC terminals was isolated by analyses of 3D confocal image stacks (see Methods). We found LRRTM4 to be localized predominantly at RBC terminals (Fig 1C) with little LRRTM4 signal at ON CBC terminals, for e.g. Type 6 axons (Fig 1C). The enrichment of LRRTM4 at RBC terminals is consistent with previous gene expression studies (Shekhar et al., 2016; Woods et al., 2018).

To determine whether LRRTM4 was localized at GABAergic synapses on RBC axons, we used Ai9/slc6a5-cre mice to visualize a subset of A17 amacrines. Presynaptic amacrine boutons surrounding RBC terminals contain vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter (VIAAT) (Schubert et al., 2013). We found LRRTM4 signal at RBC terminals apposed to VIAAT-positive A17 boutons (Fig 1D). Previous studies show that there are three distinct GABA receptor (GABAR) postsynaptic sites at RBC terminals, containing GABAAα1R, GABAAα3R or GABACR (Fletcher et al., 1998; Schubert et al., 2013). Here, we refer to each of these postsynaptic sites as distinct synapses. LRRTM4 puncta colocalized with GABAAα1R puncta (Fig 1E) at RBC terminals confirming that LRRTM4 is present at GABAergic synapses. LRRTM4, however, did not colocalize with the small fraction of GABAAα3R present on RBC terminals (Fig 1E; and see Schubert et al., 2013). Direct colocalization between LRRTM4 and GABACR could not be assessed because both antibodies were raised in the same species. However, LRRTM4 puncta at RBC terminals not colocalized with GABAAα1 are likely localized at GABAC synapses.

Because LRRTM4 is associated with glutamatergic synapses in the cortex and hippocampus (de Wit et al., 2013; Siddiqui et al., 2013) and the short isoform of LRRTM4 is enriched in these regions (Um et al., 2016), we next probed which LRRTM4 isoform is primarily expressed in the mouse retina. Previous studies have shown the presence of the long LRRTM4 isoform in monkey and mouse retina (Kawamura et al., 2018). We thus performed real-time quantitative PCR from wildtype mouse retinal homogenates and found that like the rest of the brain, the short isoform of LRRTM4 is enriched in the retina relative to the long isoform (Suppl Fig 1).

Lack of LRRTM4 disrupts GABA receptor clustering and function at RBC terminals.

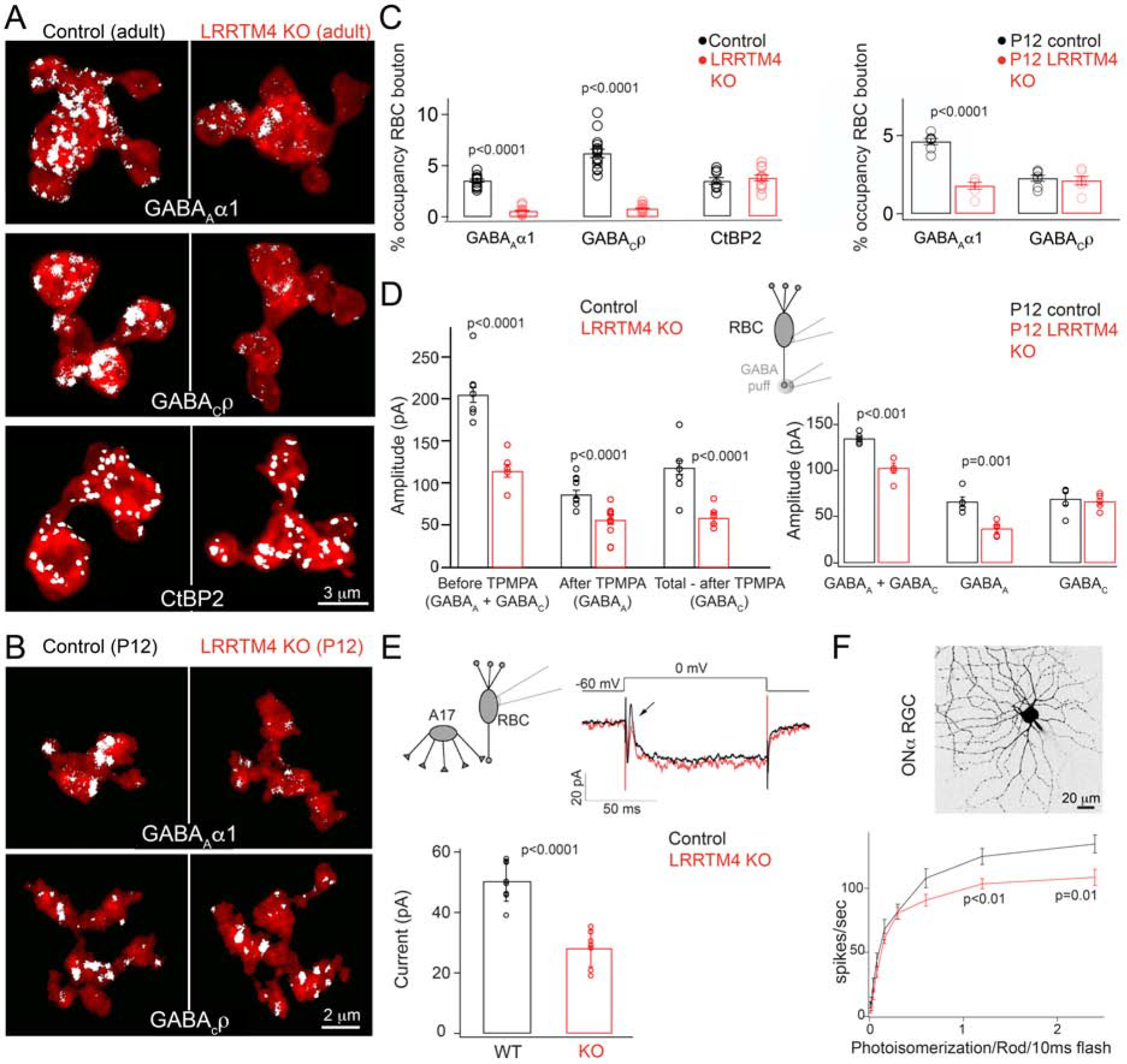

To determine whether LRRTM4 regulates GABAergic synapse assembly at RBC terminals, we compared the expression of GABAAα1R and GABACR on RBC terminals in retinas from LRRTM4 knockout (KO) animals with that of littermate controls. Immunofluorescence for both GABAAα1R and GABACR was remarkably downregulated in LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals (Fig 2A). As a control, the retinas were co-labeled with the ribbon marker, C-terminal binding protein-2 (CtBP2; Schmitz et al., 2000); the expression of CtBP2 within RBC terminals was comparable between genotypes (Fig 2A). We determined percent volume occupancy as a measure of receptor expression (see Hoon et al., 2017b). The volume occupancies of both GABAAα1 and GABAC, but not CtBP2, were significantly reduced in LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals compared to control (Fig 2C). Perhaps not surprisingly, GABAAα3 expression within RBC terminals did not vary across genotypes (Suppl Fig 2). Thus, loss of LRRTM4 specifically reduced the expression of GABAAα1 and GABACRs at RBC terminals.

Figure 2: Absence of LRRTM4 perturbs GABAergic synapses on retinal rod bipolar axon terminals.

(A) White pixels represent signal above background of immunolabeled GABAAα1 and GABACρ receptors and the ribbon marker CtBP2 within RBC terminals. Shown are examples from adult littermate control (Control) and LRRTM4 KO retina. (B) GABAAα1 and GABACρ receptor expression on P12 RBC axons of control and LRRTM4 KO. (C) Left: Quantification of percent (%) occupancy of GABAAα1, GABACρ and CtBP2 within adult RBC. Right: % occupancy of GABAAα1 and GABACρ within P12 RBC boutons. (D) Peak response amplitudes evoked by a puff of GABA at the RBC terminal during whole cell voltage-clamp recording of RBCs. The GABAC receptor antagonist TPMPA was used to separate the GABAA and GABAC mediated response components. Left: Adult RBCs, number of cells: 12 for control and 11 for KO. Right: P12 RBC responses, number of cells: 5 for control and KO. (E) Exemplar trace of the step evoked inhibitory A17 feedback current measured from adult RBCs in control and LRRTM4 KO retinas. Arrow points to the A17 mediated feedback current. Bar plot of the feedback current amplitude across genotypes. Number of cells: 8 control and 7 KO. (F) Cell-attached recordings of adult ON alpha GCs to measure spike responses to increasing flash strengths at dim-light levels. Top: Image of an ON alpha GC. Bottom: Spike rates of ON alpha GC in response to increasing flash strengths in control and LRRTM4 KO retinas. Number of recorded cells: 7 for control and 9 for KO. Significant differences are indicated by p-values; two-tailed unpaired T-test between genotypes. For each of panels C-F, N≥3 pairs of littermate control-KO animals were used.

During development, GABAAα1R expression at RBC terminals increases from ~postnatal day 12 (P12; two days before eye-opening) and GABACR expression increases between P16 and P30 (Hoon et al., 2015). To determine if LRRTM4 deficiency impairs the formation of GABAR clusters on RBC boutons, we quantified GABAAα1 and GABAC expression within P12 LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals (Fig 2B–C). GABAAα1 but not GABAC expression was significantly reduced in P12 LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals (Fig 2C). However, GABACR expression of P21 LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals was significantly reduced compared to control (P21 control RBC GABAC % occupancy = 4.12 ± 0.59; P21 LRRTM4 KO RBC GABAC % occupancy = 0.59 ± 0.11; p= 0.000046; N= 8 RBCs per genotype; 2 littermate control-KO animal pairs). These observations indicate that LRRTM4 equips GABAA and GABAC synapses across RBC terminals with adequate receptor amounts during assembly of these synapses.

To determine whether the changes in GABARs correspond to a loss in function, we performed whole-cell patch clamp recordings from RBCs and recorded the responses elicited by puffing GABA on RBC terminals (Fig 2D). After recording a GABA-evoked inhibitory current, we applied a GABACR antagonist (TPMPA) followed by a GABAAR antagonist (GABAzine) to distinguish the GABAA and GABAC-mediated components of the evoked current (Suppl Fig 3A and Fig 2D). The total GABA-evoked response and the GABAA and the GABAC components were all significantly reduced in RBCs from adult LRRTM4 KO retinas compared to controls (Fig 2D), corroborating the reduction in GABAR expression across LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals (Fig 2A). In P12 retinas, the net GABA evoked response and the GABAA component were significantly reduced in LRRTM4 KO (Fig 2D) corroborating the immunolabeling data (Fig 2B–C).

Because LRRTM4 deficiency disrupts GABAR clustering across RBC terminals, we next determined the functional consequences of LRRTM4 deficiency on reciprocal feedback received by RBCs and on retinal output (spiking responses of output ganglion cells [GCs]; Fig 1A). The amplitude of the A17-mediated feedback current (Chavez et al., 2010; Chavez et al., 2006; Grimes et al., 2015) in RBCs from LRRTM4 KO was significantly reduced, compared to controls (Fig 2E). To probe retinal output, we measured light-evoked spike responses from ON alpha GCs (a well-characterized GC that receives rod signals (Grimes et al., 2014; Murphy and Rieke, 2006; see Fig 1A)) under dim light levels. Fig 2F plots the spike responses of ON alpha GCs in LRRTM4 KO retina to 10 ms light flashes of increasing intensity. Interestingly, under these dim-light conditions that predominantly activate the rod pathway, the GC responses were nearly identical for the dimmest flashes in both LRRTM4 KO and control retinas but were significantly weaker in LRRTM4 KO retina at higher flash strengths of >1 R*/rod/flash. This suggests that absence of LRRTM4 impairs transmission of visual signals under dim light conditions when the RBC synapse is being strongly activated.

Previous studies reveal some LRRTM4 expression in the outer plexiform layer of the retina (Woods et al., 2018), where photoreceptors synapse onto BC dendrites. We measured light-evoked excitatory synaptic input onto RBCs in LRRTM4 KO and littermate control retinas (Suppl Fig 3B–C) to test transmission at the rod->RBC synapse. Responses of RBCs to increasing light intensity were comparable across genotypes (Suppl Fig 3C) indicating that the effects of LRRTM4 deletion on RBCs are largely restricted to the axonal compartment.

Ribbon synapse arrangements on RBC axon terminals are perturbed in LRRTM4 KO.

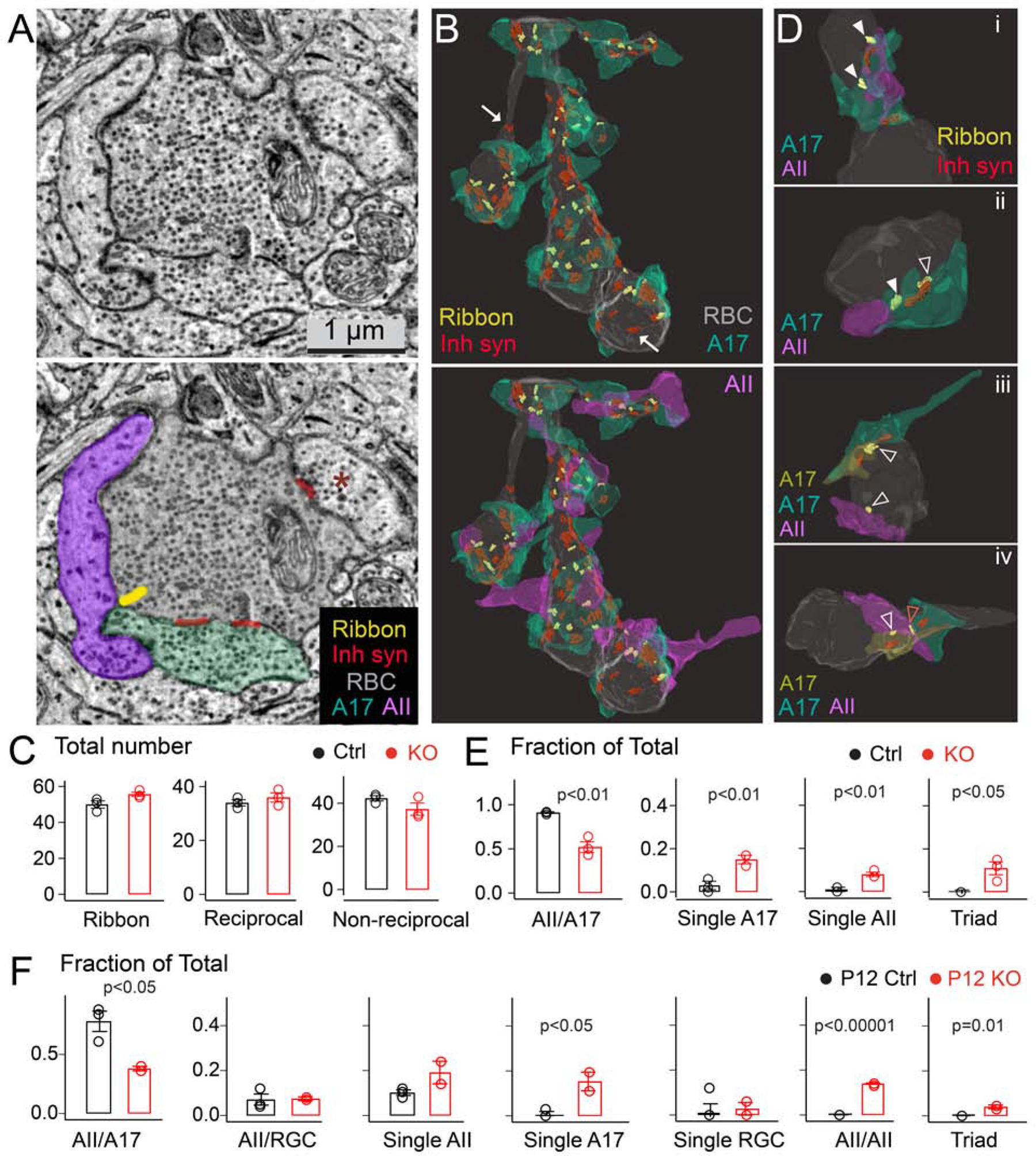

The reduced expression of GABAAR and GABACR on LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals could result from a reduction in the total number of inhibitory synapses on the RBC terminal, or from fewer GABARs at each synapse. To distinguish between these possibilities, we compared synapse arrangements of RBC terminals in LRRTM4 KO and littermate control retinas using serial block face scanning electron microscopy (SBFSEM). Synaptic ribbons in RBC axon terminals are sites of glutamate release onto processes of A17 and AII postsynaptic partners at a junction called the dyad (Fig 3A). In addition to reciprocal feedback inhibition by A17 amacrines onto the RBC terminal at synaptic dyads (Fig 1A and 3A, Chavez et al., 2010; Grimes et al., 2015), RBCs axons also receive non-reciprocal inhibitory synaptic input (Fig 3A–B, Chavez et al., 2010). We reconstructed entire RBC terminals, mapped all ribbon-associated synaptic sites, and sites of reciprocal and non-reciprocal inhibitory synapses (Fig 3B). There were no significant differences in the total number of ribbons, or in the number of inhibitory synapses on LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals compared to controls (Fig 3C). Of note, the light microscopy profiles of A17 boutons in LRRTM4 KO, visualized by labeling for GAD67, the GABA synthetic enzyme at these terminals (Schubert et al., 2013), revealed no observable differences in the KO retina compared to control (Suppl Fig 4A). We next determined the total number of ribbons apposed to each A17 bouton and found no differences in this distribution across genotypes (Suppl Fig 4B). Our estimates of the total number of ribbons within a RBC terminal are closely aligned to previous estimates (Tsukamoto and Omi, 2017).

Figure 3: Dyad synapse arrangements at rod bipolar cell terminals are perturbed in the absence of LRRTM4.

(A) Electron micrograph of the RBC terminal (top: raw image, bottom: pseudocolored) with locations of ribbons, inhibitory synapses (Inh synapse), A17 and AII output partners annotated. Non-A17 inhibitory input on the terminal is marked with a red asterisk. (B) Top: 3D reconstruction of a RBC terminal with ribbons, sites of inhibitory input and A17 boutons. Bottom: 3D view of the same terminal with both dyad partners shown at every ribbon site. Arrows point to non-reciprocal inhibitory sites. (C) Quantification of total number of ribbon synapses, A17 reciprocal synapses, and non-reciprocal inhibitory synapses in adult littermate control (Ctrl) and LRRTM4 knockout (KO) RBC terminals. (N=3 Ctrl, 3 LRRTM4 KO RBC reconstructions from 2 pairs of adult animals). (D) Examples of normal dyad arrangements (solid white arrowheads) in Ctrl (panel i) and mis-arrangements of dyad synapses in LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals (panels ii-iv; open white arrowheads; ‘Triad’ indicated by a red open arrowhead). (E) Fraction of total RBC ribbon sites with the indicated synapse arrangement in Ctrl and LRRTM4 KO terminals. (N=3 Ctrl, 3 KO reconstructions from 2 pairs of adult animals). (F) Fraction of total RBC ribbon sites with the indicated synapse arrangement in P12 terminals. (RGC: retinal ganglion cell, N=3 P12 Ctrl, 2 KO P12 RBC reconstructions). P values listed; two-tailed unpaired T-test across genotypes.

Next, we determined the identities of the postsynaptic partners at the RBC ribbon synapses. In littermate controls, ~91% of ribbons were correctly positioned at dyads across processes of an A17 and AII cell pair (Fig 3D, top panel i and Fig 3E). In the LRRTM4 KO, only ~52% of ribbons were correctly located at A17/AII dyads (Fig 3D panels ii-iv and Fig 3E). Instead, a significant number of ribbons in the LRRTM4 KO were erroneously positioned opposite a single A17 process (Fig. 3Dii), a single AII process (Fig. 3Diii), at dyads with two AII partners or apposed to three postsynaptic partners (either two AII and one A17 or two A17 and one AII) forming a ‘triad’ configuration (Fig 3D iv red arrowhead and 3E). Triad profiles were never observed at any ribbon synapses of RBCs in control retinas. The rate of error of positioning ribbons opposite two A17 partners, however, was comparable across genotypes (see Table of all dyad arrangements in Fig 4B; see Suppl Fig 5 for EM profiles of dyad errors). To determine if errors in dyad assembly in the KO occur during synapse development, we repeated the analyses for P12 LRRTM4 KO retinas. In control P12 RBC terminals, ~78% of ribbons were correctly positioned at dyads across an A17 and AII cell pair (Fig 3F). In contrast, only ~38% of ribbons were correctly positioned in LRRTM4 KO P12 terminals (Fig 3F). The errors of positioning ribbons at a single A17 (A17 monad), an AII-AII dyad, and a three-partner triad (never seen in control P12 RBCs) were significantly increased for P12 LRRTM4 KO RBCs. Taken together, our EM reconstructions revealed a significant disruption in the accuracy of dyad ribbon synapse assembly in the absence of LRRTM4.

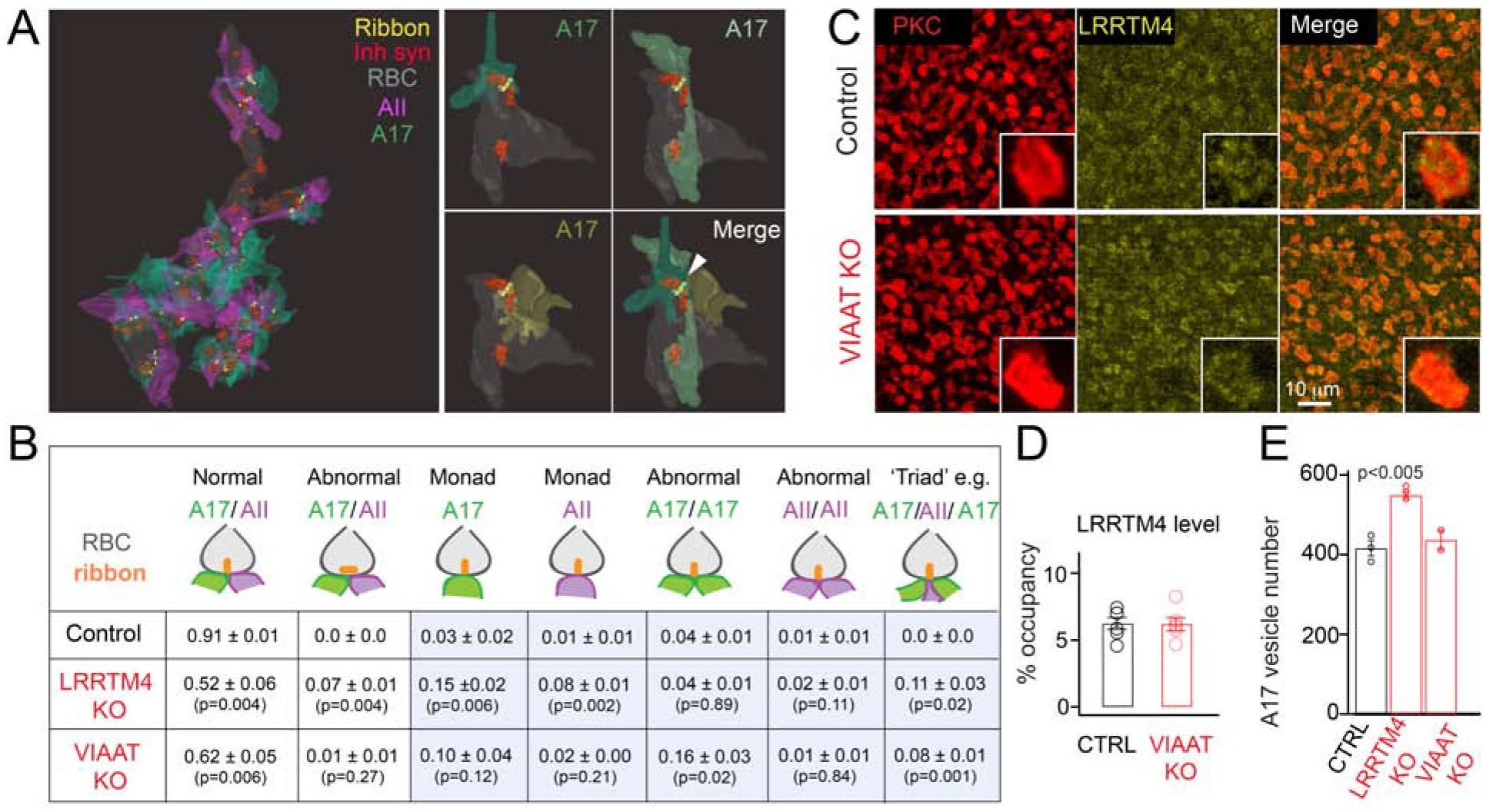

Figure 4: Impaired inhibitory input onto rod bipolar cell axons results in structural mis-arrangements of ribbon synapses.

(A) Left: 3D view of the RBC terminal in the VIAAT KO retina. Ribbons, inhibitory synapses and A17 and AII partner profiles are shown. Right: Example of a RBC ‘triad’ ribbon synapse with three A17 partners (white arrowhead) in the VIAAT KO retina. (B) Table summarizing adult RBC dyad arrangements from reconstructions across genotypes. N=3 Control, 3 LRRTM4 KO and 2 VIAAT KO RBCs from 2 pairs of littermate control and KO animals. The numbers depict the average fraction (mean ± S.E.M) of ribbon synapses with each type of illustrated structural arrangement. In controls, 0.01 ± 0.01 ribbons were also found juxtaposed to a single AII or an A17 partner, and an unidentified, presumably ganglion cell partner (not included in summary table). Triad configurations include an AII and two A17 partners (illustrated here), three A17 partners or two AII with one A17 partner. P values listed for two-tailed unpaired T-test between control and LRRTM4KO, and between control and VIAAT KO. Abnormal monad, dyad and triad arrangements are enclosed within blue boxes and include both vertical and horizontal ribbon arrangements. (C) LRRTM4 expression at PKC-immunopositive RBC terminals appears normal in the VIAAT KO retina. (D) Quantification of the percent (%) occupancy of LRRTM4 within adult RBC boutons of control (CTRL) and VIAAT KO retinas is comparable. (N>3 animal pairs). (E) Quantification of synaptic vesicle number within A17 boutons in CTRL, LRRTM4 KO and VIAAT KO (N=3 Control, 3 LRRTM4 KO and 2 VIAAT KO from 2 pairs of littermate control and KO animals; for each RBC 10 A17 boutons were averaged). P value listed for two-tailed unpaired T-test between control and LRRTM4 KO.

RBC axon terminals in VIAAT-deficient retina also demonstrate ribbon synapse mis-arrangements.

LRRTM4 KO RBC terminals demonstrate diminished GABAergic synapse function and perturbed dyad arrangements. Thus, GABAergic input to the RBC terminal could regulate the assembly of RBC dyad synapses. If so, we would expect RBC dyad mis-arrangements in other mutants with perturbed GABAR expression on RBC terminals. Our previous work showed that expression of GABAAα1R and GABACR on RBC terminals are significantly reduced in retinas lacking VIAAT (Hoon et al., 2015). We thus examined VIAAT KO retinas by SBFSEM to determine if loss of GABAergic drive onto RBC terminals results in mis-arrangements of their dyad synapses (Fig 4A). We found that a significant number of ribbons in VIAAT KO RBC terminals were erroneously localized at triad configurations (example of a three A17 triad profile shown in Fig 4A, quantifications in Fig 4B), or were found apposed to two A17 partners (Fig 4B). Accordingly, there was a significant decrease in the number of ribbons correctly juxtaposed to a pair of AII and A17 partners in the VIAAT KO RBC terminals, compared to control (Fig 4B). This phenotype resembles our observation in the LRRTM4 KO, with both mutants showing a significant reduction in the number of correctly assembled AII/A17 dyads, albeit with differences in the occurrences of specific types of mis-arrangements (Fig 4B). Dyad mis-arrangements in both the LRRTM4 KO and VIAAT KO could reduce the transfer of visual information from RBC terminals to output GCs, because AII amacrines are the intermediates that convey RBC output to the GCs (see Fig 1A) and fewer dyads involved AII processes in both KOs (~19% of RBC ribbons in LRRTM4 KO and ~26% of RBC ribbons in VIAAT KO are not apposed to an AII partner; Fig 4B). Together, our observations suggest that presynaptic inhibition could regulate the accuracy of RBC dyad synapse arrangements, and synapse mis-arrangements in the LRRTM4 KO could be a consequence of perturbed GABAergic transmission.

Both LRRTM4 and VIAAT mutants exhibit a downregulation of GABAAR and GABACR on RBC terminals (Fig 2 and Hoon et al., 2015) and ribbon synapse mis-arrangements (Fig 4). We next asked whether the deficits observed in VIAAT KO RBCs could be because LRRTM4 is downregulated when GABA release is impaired. To this end, we determined the expression levels of LRRTM4 at RBC terminals of VIAAT KO retinas. LRRTM4 expression on RBC terminals remained comparable across VIAAT KO and control retinas (Fig 4C, % occupancy plots in Fig 4D), suggesting that presynaptic neurotransmission and LRRTM4 regulate GABARs on RBC terminals via distinct mechanisms. Nevertheless, two key phenotypes shared between the VIAAT KO (Hoon et al., 2015) and LRRTM4 KO suggest that perturbations in RBC presynaptic inhibition may underlie mis-assembled dyads in both KOs: (i) both mutants display reduced GABAR function at RBC terminals (GABAR deficit in VIAAT KO shown in Hoon et al., 2015) and (ii) there is a significant reduction in the number of correctly assembled RBC dyads in both mutants.

Another observation which points to distinct roles of inhibitory neurotransmission and LRRTM4 in the assembly of RBC dyads is the observation of presynaptic alterations in A17 boutons in the LRRTM4 KO that were not present in the VIAAT KO retina. We found that the number of synaptic vesicles in A17 boutons was significantly increased in the LRRTM4 KO retina, but not in VIAAT KO retina (Fig 4E), underscoring a possible trans-synaptic role of LRRTM4 during assembly of A17-RBC synaptic connections.

A candidate presynaptic interacting partner of LRRTM4 that might mediate such trans-synaptic functions is neurexin. Neurexin is a major presynaptic organizing protein family (Sudhof, 2017) that binds to LRRTM4, potentially through protein domain (de Wit et al., 2013; Um et al., 2016) and/or heparan sulfate-mediated interactions (Siddiqui et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2018). Indeed, using co-immunoprecipitation assays, we found an interaction between retinal LRRTM4 and the presynaptic protein neurexin (Suppl Fig 6A). Thus, neurexin is likely the trans-synaptic ligand for LRRTM4 on the A17 side of this synapse. Although we were unable to co-immunoprecipitate LRRTM4 with GABAAα1R either from the retina or from co-transfected HEK293T cells (Suppl Fig 6B–D), neurexin was found to directly bind to GABAAα1R (Zhang et al., 2010), suggesting that a LRRTM4-neurexin-GABAAα1R complex may function in the development of A17 synapses onto RBC terminals.

DISCUSSION

Our results reveal an unexpected role for LRRTM4 in the assembly and function of inhibitory feedback synapses of the retinal circuit responsible for dim-light vision. Unlike its role for organizing dendritic glutamatergic synapses in other parts of the brain (de Wit et al., 2013; Siddiqui et al., 2013), in the retina, LRRTM4 organizes inhibitory synaptic connections on the axon terminals of RBCs. Our observations in the VIAAT KO also reveal a novel role of GABAergic input onto RBCs in regulating the structural arrangements of RBC ribbon synapses.

LRRTM4 organizes GABAA and GABAC synapses at RBC terminals.

Organizers of inhibitory synapses at axon terminals mediating presynaptic inhibition have not been identified previously. In the retina, organizing proteins associated with GABAA and GABAC synapses of RBC terminals have remained unknown. Canonical inhibitory synapse adhesion and scaffolding proteins such as Neuroligin 2 and Gephyrin are not enriched at these GABAergic postsynapses (Schubert et al., 2013). The microtubule associated protein1b (MAP 1b) though involved in a direct interaction with GABACR (Hanley et al., 1999) is not necessary for retinal GABACR clustering (Meixner et al., 2000). Our analyses of LRRTM4 KO retinas thus uncovers the first trans-synaptic organizing protein at GABAergic synapses mediating presynaptic inhibition. We could not identify a direct interaction between recombinant GABAAR and LRRTM4 (Suppl Fig 6). Thus, our data suggests that LRRTM4 could mediate the clustering and function of GABARs on RBC terminals through an indirect interaction, potentially via a trans-synaptic interaction of neurexin with both LRRTM4 (Suppl Fig 6A) and GABAAα1R (Zhang et al., 2010).

Our results reveal a deviation from the traditional compartmentalization of excitatory vs inhibitory synaptic organizer proteins in the CNS, implying that the same synaptic organizer, LRRTM4, can regulate the structural arrangements and function of both excitatory and inhibitory synapses, in a circuit-specific manner. Similarly, in the CNS, Neuroligin-3 and the Slit-Robo Rho-GTPase Activating Protein (SRGAP) function at both excitatory and inhibitory synapses (Budreck and Scheiffele, 2007; Fossati et al., 2016). In the retina, however, Neuroligin-3 is enriched at inhibitory postsynapses; a lack of Neuroligin-3 specifically reduces the clustering of GABAAα2R synapses (Hoon et al., 2017a), normally localized to a specific amacrine-GC circuit. Together, these observations underscore the different roles a given synapse organizing protein can perform across diverse brain circuits. The specific localization of LRRTM4 to rod and not cone BCs is also note-worthy, indicating a function together with ELFN1 (Cao et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017) in development of the rod pathway. This is consistent with the role of LRRTM4 in synaptic specificity in the hippocampus wherein it mediates synapse development in the dentate gyrus but not in the CA1 (Siddiqui et al., 2013).

LRRTM4 is localized at A17-RBC connections and its loss results not just in postsynaptic alterations in receptor clustering but also in presynaptic alterations in synaptic vesicle clustering at A17->RBC synapses. One can thus infer that LRRTM4 is a key trans-synaptic organizing protein at A17-RBC connections. Previous single cell profiling studies corroborate that LRRTM4 is on the postsynaptic RBC side of these synapses (Shekhar et al., 2016; Woods et al., 2018). Additionally, our retinal co-immunoprecipitation results revealed that retinal LRRTM4 interacts with neurexins. Since Drop-seq data revealed that all retinal amacrine types express Neurexins (Macosko et al., 2015), our observations unveil the neurexin-LRRTM4 trans-synaptic interaction as a molecular organizer of the A17->RBC inhibitory feedback synapse.

GABAergic input onto RBC terminals regulates ultrastructural arrangements of ribbon synapses.

Our findings extend the role of GABAergic input onto RBC terminals beyond regulation of glutamate release, as disruption in this input reduces the accuracy of ribbon synapse assembly. Our comparative analyses of the synaptic ultrastructure of LRRTM4 and VIAAT KO RBC terminals, however, suggest that presynaptic inhibition does not affect the total number of ribbon or inhibitory synapses. GABAergic drive onto RBCs does not regulate LRRTM4 levels, thus LRRTM4 works in an activity-independent manner to regulate synaptic levels of GABAAR and GABACR at RBC terminals. An important consideration in this regard is that blocking GABA synthesis (GAD67 KO; Schubert el al., 2013) or vesicular release of inhibitory neurotransmitters (VIAAT KO; Hoon et al., 2015) does not impact the initial accruing of GABAAα1Rs on RBC terminals, but affects the maintenance of these receptor clusters (GABAA α1R and GABACRs not maintained in VIAAT KO; GABAAα1Rs not maintained in GAD67 KO). In contrast, absence of LRRTM4 in the retina prevents clustering of GABAAα1Rs at an early time point during circuit assembly (before eye-opening). These observations underscore a ‘synaptogenic’ role for LRRTM4 in the assembly of inhibitory synapses on RBC terminals, and a subsequent role for neurotransmission in the maintenance of GABAR synapses on RBC terminals.

Functional recordings of GC responses probing rod mediated signaling shows that the efficacy of signal transmission via the RBC->AII pathway is altered in the LRRTM4 KO retina. Interestingly, this alteration is only present for dim light stimuli that perhaps strongly activates the RBC synapse. This could possibly be due to reduced GABAergic presynaptic inhibition at the RBC terminal in LRRTM4 KO retinas which under normal conditions prevents the RBC output synapse from undergoing vesicle depletion and synaptic depression (Grimes et al., 2015; Oesch and Diamond, 2011). In addition to reduced presynaptic inhibition at the RBC terminal, synaptic dyad mis-arrangements in the LRRTM4 KO could also contribute to the reduced sensitivity of dim light signaling via the rod bipolar pathway to the ON alpha GCs.

In sum, our observations uncover a novel role for LRRTM4 in the assembly and function of a sensory circuit. These findings are especially important for the retina, as mutations in LRRTM4 have been associated with hereditary macular degeneration and vision deficits (Kawamura et al., 2018) and it will be important to evaluate if the vision deficits associated with LRRTM4 mutations are linked to synaptic defects at the RBC terminal or whether LRRTM4 plays additional roles at other retinal synapses. LRRTM4 may also operate at other inhibitory synapses of the CNS. LRRTM4 has been linked to cognitive impairments such as autism spectrum disorders (Michaelson et al., 2012; Pinto et al., 2010) and circuit excitation/inhibition imbalances contribute to the development and maintenance of these disorders (Lee et al., 2017). Future studies evaluating the localization and function of LRRTM4 across diverse CNS circuits are therefore needed for a holistic understanding of the synaptic mechanisms underlying cognitive dysfunction.

STAR METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Mrinalini Hoon (mhoon@wisc.edu). This study did not generate any unique reagents.

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of the University of Washington and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Animal Care Committee of the University of British Columbia, and the National Institutes of Health. Age matched littermate control and LRRTM4 knockout (Siddiqui et al., 2013) and littermate control and retina-specific VIAAT knockout (α-Pax6cre crossed to VIAAT conditional knockout animals; Hoon et al., 2015) adult mice (2–4 months), of both sexes were utilized. Additionally, postnatal day 12 (P12) and P21 LRRTM4 knockout and littermate control animals were used. To visualize RBCs and ON cone bipolar cells, the Grm6-tdtomato mouse line was used (Kerschensteiner et al., 2009) in which the metabotropic glutamate receptor-6 (mGluR6) promoter drives red fluorescent protein expression. The Ai9 reporter line (Jackson Laboratory, B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J) was crossed to the slc6a5-cre transgenic (GENSAT) to generate the Ai9/slc6a5-cre line in which some A17 amacrine cells are fluorescently labeled.

METHOD DETAILS

Immunohistochemistry

Immunolabeling was performed on whole-mount retinas isolated in cold oxygenated mouse artificial cerebrospinal fluid (mACSF, pH 7.4) containing (in mM): 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgCl2, 1 NaH2PO4, 11 glucose, and 20 HEPES. Retinas were flattened on a filter paper (Millipore, HABP013), fixed for 15 mins in 4% paraformaldehyde prepared in mACSF, rinsed in phosphate buffer (PBS) and incubated with primary antibody in blocking solution containing 5% donkey serum and 0.5 Triton X-100 at 4°C for 3–4 days. Antibodies utilized were as follows: anti-PKC (1:1000, mouse, Sigma); anti-LRRTM4 (BC-262) (1:500, rabbit, Siddiqui et al., 2013); anti-VIAAT (1:1000, guinea pig, Synaptic Systems); anti-GABAAα1 (1:5000, guinea pig, J.M Fritschy); anti-GABACρ (1:500, rabbit, R. Enz, H. Wassle and S. Haverkamp); anti-CtBP2 (1:1000, mouse, BD Biosciences), anti-GABAAα3 (1:3000, guinea pig, J.M Fritschy). After incubation with primary antibodies, retinas were rinsed in PBS and incubated with anti-isotypic Alexa Fluor (1:1000, Invitrogen) or DyLight (1:1000, Jackson Immunoresearch) secondary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Thereafter retinas were rinsed in PBS and mounted on slides with Vectashield antifade mounting medium (Vector Labs).

Confocal microscopy and Image analyses

Images were acquired with an Olympus FV 1000 laser scanning confocal microscope and a 1.35 NA 60X oil immersion objective or a Leica SP8 confocal microscope and a 1.4 NA 63X oil immersion objective at a voxel size around 0.05–0.05–0.3 μm (x-y-z). Further processing of image stacks was performed using MetaMorph (Molecular Devices) and Amira (Thermo Fisher Scientific) software. Because neighboring synaptic puncta could not always be resolved by confocal microscopy for quantification, we determined the volume occupied by the receptor signal within the BC terminal and divided this value by the volume of the BC terminal to obtain a ‘percent volume occupancy’ of receptor expression (see Hoon et al., 2017b). To quantify % occupancy of receptor immunoreactivity within bipolar cells, bipolar cell processes were first masked in 3D using the LabelField function of Amira. Receptor signal within the bipolar process was next isolated with the Amira Arithmetic tool. A threshold was thereafter applied to eliminate background pixels and the total volume of ‘receptor pixels’ above background was then expressed as a percent (%) occupancy relative to the volume of the bipolar cell process (for more details on threshold selection and volume occupancy, see Hoon et al., 2017b; Hoon et al., 2015).

Electrophysiology recordings

Experiments were conducted on whole mount and slice (200 μm thick) preparations taken from dark-adapted LRRTM4 knockout and littermate control mice. Isolated retinas were stored in oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) Ames medium (Sigma) at ~32°C–34°C, and once under the microscope, tissue preparations were perfused by the same Ames solution at a rate of ~8 mL/min. The retina was isolated from the choroid and pigment epithelium and mounted flat in a recording chamber. The retina was mounted ganglion cell side up for ganglion cell recordings (Sinha et al., 2016). The retinas were embedded in agarose and sliced as previously described (Hoon et al., 2015) for all bipolar cell recordings. Retinal neurons were visualized and targeted for cell-attached and whole-cell patch clamp recordings using infrared light (>900 nm).

Voltage-clamp recordings from RBCs were obtained using pipettes (10–14 MΩ) filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM) the following: 105 Cs methanesulfonate, 10 TEA-Cl, 20 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 2 QX-314, 5 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Tris-GTP, and 0.1 Alexa-594 hydrazide (~280 mOsm; pH ~7.2 with KOH). (1,2,5,6-Tetrahydropyridin-4-yl) methylphosphinic acid (TPMPA, 50 μM; Tocris, Bristol, United Kingdom) and GABAzine (20 μM; Tocris, Bristol, United Kingdom) was added to the perfusion solution as indicated in Suppl Fig 3. To isolate excitatory or inhibitory synaptic input in voltage-clamp recordings, cells were held at the estimated reversal potential for inhibitory or excitatory input of ~−60 mV and ~+10 mV. Absolute voltage values were not corrected for liquid junction potentials (−8.5 mV). GABA was applied using a Picospritzer II (General Valve) connected to a patch pipette (resistance, ~5–7 MΩ). GABA (200 μM) was dissolved in Hepes-buffered Ames medium with 0.1 mM Alexa-488 hydrazide and applied with the puff pipette. The puffing direction and the duration of the 50 ms puff were chosen such that the axonal terminal of the voltage-clamped RBC was completely covered by the puff. To quantify GABA-evoked currents, peak amplitude relative to the preapplication or pre-stimulus baseline current, were determined and averaged across cells. To determine the amplitude of the A17-mediated GABAergic feedback current in RBCs, step-evoked feedback experiments were done in accordance with previous studies (Chavez et al., 2010; Chavez et al., 2006; Grimes et al., 2015). Reciprocal feedback onto the RBC was evoked by depolarizing the RBC from −60 mV to 0 mV for a duration of 100 ms under whole cell voltage clamp (Chavez et al., 2010; Chavez et al., 2006; Grimes et al., 2015). This elicited an inward sustained Cav (voltage-gated calcium) channel-mediated current and a transient outward feedback current previously shown to be mediated by A17 reciprocal feedback (Fig 2E; Chavez et al., 2010; Chavez et al., 2006; Grimes et al., 2015). Recordings were only included for further analysis when feedback responses stabilized within the first 30–60 s after break-in. The amplitude of the feedback current was measured as the difference between the peak and the baseline at the latter part of the stimulus (60–90 ms).

Light responses of RBCs were recorded using whole-cell recording approaches. Light responses measured under whole-cell conditions typically lasted 2–4 min to minimize wash out. Cell-attached recordings of dim light-evoked action potentials were performed from ON alpha ganglion cells. The exemplar image of an ON alpha cell in Fig. 2F was acquired after whole-cell recording with Alexa-488 dye mixed in the pipette internal solution. Light stimuli were delivered from an LED with a peak output wavelength of 470 nm. Calibrated photon densities were estimated in photoisomerizations per rod (Rh*/rod), assuming a rod collecting area of 0.5 μm2 (Field and Rieke, 2002).

3D block face serial scanning electron microscopy and reconstructions

Flat-mounted retinas were immersion fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) followed by staining, dehydration, and embedding in Durcupan resin using a previously established protocol (Della Santina et al., 2016). A Zeiss 3View Serial block face scanning electron microscope was used to image retinal regions comprising a 2×2 montage of tiles at a section thickness of 50nm, with each tile comprising 8600×8600 pixels (approximately 48×48micron). Image stacks were aligned, and cells reconstructed using TrakEM2 (NIH). Amira was used for visualization and display of reconstructed profiles.

RBC terminals were identified by their characteristic morphology (Hoon et al., 2014; Tsukamoto and Omi, 2017; Wassle, 2004). Ribbons across RBC terminals were apposed to two amacrine interneurons, one of which (the A17) makes a reciprocal inhibitory synapse back onto the RBC terminal it receives input from (Hoon et al., 2014; Tsukamoto and Omi, 2017; Wassle, 2004). Both ribbon synapses and inhibitory synapses were easily identifiable in the electron microscopic images allowing the connectivity of all dyad partners to be reconstructed in 3D. Inhibitory synapses were identified as profiles with accumulation of synaptic vesicles along a release site and thickening of the pre- and postsynaptic membranes as described previously (Gray, 1969). For adult retinas, 3 Control, 3 LRRTM4 KO and 2 VIAAT KO RBC terminals were reconstructed from 2 pairs of littermate control-KO animals. Dyad partners at each ribbon synapse were identified and reconstructed. Average number of ribbons (mean ± SEM) across adult RBC terminals were: Control = 50.00 ± 2.08; LRRTM4 KO = 55.67 ± 1.20; VIAAT KO = 52.50 ± 5.50. For quantifying synaptic vesicles in A17 boutons, the touch-count tool (Image J/TrakEM2) was utilized and the total number of synaptic vesicles across all planes of the A17->RBC synaptic contacts was quantified. As the SBFSEM section thickness is 50 nm, the number of synaptic vesicles is likely to be an under-estimate. For each RBC terminal, A17 synaptic vesicle number was averaged from measurements from ten A17 boutons contacting that RBC. The littermate control mean was an average from 3 RBC terminals, the LRRTM4 KO mean was averaged from 3 RBC terminals and the VIAAT KO mean was averaged from 2 RBC terminals. Average A17 synaptic vesicle number were Control = 416.03 ±19.07; LRRTM4KO = 548.55 ± 9.34; VIAAT KO = 436.55 ± 24.45. For the Postnatal day 12 dataset, 3 control and 2 LRRTM4 KO RBCs were reconstructed.

Real Time - Quantitative PCR from retina samples

Retina samples were collected from three 5–6 weeks old C57BL6 mice. Mice were decapitated under deep anesthesia by isoflurane, retinas were dissected and immediately processed for RNA extraction (PureLink RNA Mini Kit, Invitrogen). Total RNA was retrotranscribed to cDNA ensuring that the same amount of RNA was used for each sample (SuperScript™ IV VILO™ Master Mix with ezDNase™ Enzyme). Real time quantitative polymerase chain reaction was then performed in one run for all target and control genes (PowerUp SYBR™ Green Master Mix, Applied Biosystems) in a QuantStudio-5 Real-Time PCR System. Efficiency of all primers was determined to between 0.9 and 1.05. Fold change for LRRTM4 isoforms was calculated using the modified ΔΔCt method with the Pfaffl correction (Bustin et al., 2009; Pfaffl, 2001).

Coimmunoprecipitation

Retinae were isolated from wildtype mice and washed once with ice-cold PBS, resuspended in either Complexiolyte 48 (Logopharm) or cold 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM, Avanti Polar Lipids) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Lysates were incubated for 30 min at 4°C and centrifuged at 14,000g for 20 min to separate the insoluble fraction. The supernatant was incubated with Protein G sepharose beads pre-conjugated for 12 hours at 4°C with the following antibodies: anti-pan-neurexin (Millipore, ABN161-I) (Suppl Fig 6Ai), anti-LRRTM4 (BC262, Siddiqui et al, 2013) (Supply Fig 6A ii), anti-LRRTM4 (Neuromab, N205B/22; AB_11211973) (Suppl Fig 6B) or anti-GABAAα1 (Millipore) (Suppl Fig 6C). After overnight incubation, the beads were washed 3 to 4 times with either Complexiolyte 48 dilution buffer or 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% DDM. Bound proteins were eluted with 2X Laemmli buffer. To detect native neurexin (Suppl Fig 6Aii), immunoprecipitates were incubated with Heparinases I, II, and III for 2 hours at 37°C in the heparinase digestion buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH7, 100 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, protease inhibitors) prior to elution.

For cell culture experiments, HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing either LRRTM4-CFP and HA-GABAAα1, GABAAβ2, GABAAγ2 or LRRTM4-CFP and HA-Glycine receptor α1. Cells were washed two times with 25mM Sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), incubated in the absence or presence of the crosslinker, 2mM Dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP) in 25 mM Sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 45 mins followed by quenching with 200 mM Tris, pH 7.4. The cells were lysed in 50 mM Sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl containing 0.5% Triton × 100. Lysates were incubated for 30mins at 4°C and centrifuged at 14,000g for 20 min to separate the insoluble fraction. The supernatant was incubated with Protein G sepharose beads pre-conjugated for 12 hours at 4°C with anti-HA (3F10) (Roche, Cat#11867431001; AB_390919). After overnight incubation, the beads were washed 3 to 4 times with buffer and eluted in 2X Laemmli buffer.

Immunoblotting

Protein concentrations were normalized using the Coomassie (Bradford) protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and run on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels followed by transfer to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore). Blots were blocked in 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline/0.001% Tween-20 and incubated with one of the following antibodies: anti-LRRTM4 (mouse, 1:1000, N205B/22, Neuromab), anti-pan-Nrx (rabbit, 1:2000, ABN161, Millipore), Anti-Nrxn1α (Frontier Institute Co., Ltd, AF870), anti-GABAAα1 (NeuroMab clone N95/35), anti-GFP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A11122) and secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugate from Southern Biotech), mouse anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Conformation Specific, L27A9 mAb antibody, Cell Signaling Technology, 3678) for chemiluminiscence. Immunoblots were detected using the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent substrate (Millipore), Clarity Western ECL or Clarity Max Western ECL substrate substrate (Bio-rad) and a Bio-Rad gel documentation system. In Suppl Fig 6A ii, since the antibodies used in immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting originated from the same host species, a conformation specific secondary antibody that does not bind to reduced and denatured IgGs was used in immunoblotting. This was done to prevent the masking of the various Nrx isoforms by IgG-H and L of the antibody used in the co-immunoprecipitation experiment.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical details of experiments including number of cells/animals analyzed is provided in the Figure legends. Additional details for the EM data set are also provided in the Methods Details section. A two-tailed unpaired T-test was performed across genotypes to determine significance.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

The datasets supporting the current study have not been deposited in a public repository because of extremely large file sizes but are available from the corresponding author on request.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-PKC clone MC5 | Sigma | Catalog # P5704 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-LRRTM4 (BC262) | Siddiqui et al., 2013 | Generated in Ann Marie Craig’s Lab |

| Guinea pig polyclonal anti-VIAAT | Synaptic Systems | Catalog # 131004 |

| Guinea pig polyclonal anti-GABAAα1 | Fritschy and Mohler 1995 | Generated in Jean-Marc Fritschy’s Lab |

| Guinea pig polyclonal anti-GABAAα3 | Fritschy and Mohler 1995 | Generated in Jean-Marc Fritschy’s Lab |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-GABAC | Enz et al., 1996 | Generated in Heinz Wässle and Joachim Bormann’s Lab. |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-CtBP2 | BD Biosciences | Catalog # 612044 |

| Rabbit anti-GFP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A11122, RRID: AB_221569 |

| Rat anti-HA (3F10) | Roche | Cat#11867431001; RRID: AB_390919 |

| Rabbit anti-pan-Nrx1 | Millipore | Cat#ABN161-I; RRID: AB_11211973 |

| Mouse anti-LRRTM4 | Neuromab | Cat#N205B/22; RRID: AB_10674105 |

| anti-GABAA α1 | Millipore | Cat#06–868; RRID: AB_310272 |

| Goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugate | Southern Biotech | Cat#4030–05; RRID: AB_2687483 |

| Goat anti-mouse HRP conjugate | Southern Biotech | Cat#1030–05; RRID: AB_2619742 |

| Mouse Anti-rabbit IgG | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3678; RRID: AB_1549606 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Ames | Sigma | 1420 |

| GABAzine | Sigma | SR-95531 |

| TPMPA | Tocris | 1040 |

| GABA | Sigma | A2129 |

| Alexa 488-hydrazide | Invitrogen | A10436 |

| Vectashield antifade mounting medium | Vector Labs | Catalog# H-1000 |

| Heparinase I | Sigma | Cat# H2519 |

| Heparinase II | Sigma | Cat# H6512 |

| Heparinase III | Sigma | Cat# H8891 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: Grm6-tdtomato | Rachel Wong and Daniel Kerschensteiner (Kerschensteiner et al., 2009) | N/A |

| Mouse: LRRTM4 KO | Ann Marie Craig and Tabrez Siddiqui (Siddiqui et al., 2013) | N/A |

| Mouse: α-Pax6Cre | Guillermo Oliver (Marquardt et al., 2001) | N/A |

| Mouse: VIAAT conditional KO; Slc32a1tm1Lowl/J strain | Jackson Labs | JAX Stock No: 012897 |

| Mouse: Ai9 reporter; B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J strain | Jackson Labs | JAX Stock No: 007909 |

| Mouse: slc6a5-Cre | Allen Brain Institute (GENSAT) | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| LRRTM4 long isoform forward primer TCTGGCTCCAGGGAGTGTGAG |

Um et. al., 2016 | N/A |

| LRRTM4 long isoform reverse primer CTTGTTGATGTGGAGAGGCTGGTG |

Um et. al., 2016 | N/A |

| LRRTM4 short isoform forward primer TCTGGCTCCAGGGAGTGTGAG |

Um et. al., 2016 | N/A |

| LRRTM4 short isoform reverse primer GATTAGCCACACCACTAGAGCCTCA |

Um et. al., 2016 | N/A |

| Synaptophysin forward primer TAATCTGGTCAGTGAAGCCCA |

This paper | N/A |

| Synaptophysin reverse primer AGGATATGGGGATGGGAAGG |

This paper | N/A |

| Gapdh forward primer TCAGGAGAGTGTTTCCTCGT |

This paper | N/A |

| Gapdh reverse primer TTGAATTTGCCGTGAGTGGA |

This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| LRRTM4-CFP | Siddiqui et al., 2013 | N/A |

| HA-Glycine Receptor | Ge et al., 2018 | N/A |

| HA-GABA receptor a1 | Ge et al., 2018 | N/A |

| HA-GABA receptor b2 | Ge et al., 2018 | N/A |

| HA-GABA receptor g2 | Ge et al., 2018 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| IGOR Pro | WaveMetrics | https://www.wavemetrics.com/ |

| MATLAB | Mathworks | https://ch.mathworks.com/products/matlab |

| Symphony | Symphony-DAS | https://github.com/symphony-das |

| ImageJ | NIH | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Amira | ThermoFisher Scientific | https://www.fei.com/software/amira/ |

Highlights:

LRRTM4 is at presynaptic inhibitory synapses on retinal rod bipolar axon terminals.

LRRTM4 regulates GABAA and GABAC synapse clustering and function at rod bipolar axons.

Arrangement of synaptic ribbons at dyad configurations is disrupted without LRRTM4.

Impaired GABAergic input onto bipolar terminals could underlie dyad mis-arrangements.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH Grants EY10699 (to R.O.W.), EY026070 (to R.S.), EY11850 (to F.R.), Vision Core Grant EY01730 (to M. Neitz), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant RGPIN-2015-05994 (to T.J.S), Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant Fdn-143206 and a Canada Research Chair (to A.M.C.), the McPherson Eye Research Institute’s Rebecca Meyer Brown/Retina Research Foundation Professorship (to M.H), and an unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. to UW Madison Department of Ophthalmology. We thank J.M. Fritschy, R. Enz, S. Haverkamp and H. Wässle for generously providing GABAA and GABAC receptor antibodies, R. T. Roppongi for experimental assistance and E. Parker, M. Zhang and K. Oda for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Budreck EC, and Scheiffele P (2007). Neuroligin-3 is a neuronal adhesion protein at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses. Eur J Neurosci 26, 1738–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, et al. (2009). The MIQE guidelines: minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55, 611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Sarria I, Fehlhaber KE, Kamasawa N, Orlandi C, James KN, Hazen JL, Gardner MR, Farzan M, Lee A, et al. (2015). Mechanism for Selective Synaptic Wiring of Rod Photoreceptors into the Retinal Circuitry and Its Role in Vision. Neuron 87, 1248–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez AE, Grimes WN, and Diamond JS (2010). Mechanisms underlying lateral GABAergic feedback onto rod bipolar cells in rat retina. J Neurosci 30, 2330–2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez AE, Singer JH, and Diamond JS (2006). Fast neurotransmitter release triggered by Ca influx through AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Nature 443, 705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski A, Terauchi A, Strong C, and Umemori H (2015). Distinct sets of FGF receptors sculpt excitatory and inhibitory synaptogenesis. Development 142, 1818–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalva MB, McClelland AC, and Kayser MS (2007). Cell adhesion molecules: signalling functions at the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci 8, 206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J, O’Sullivan ML, Savas JN, Condomitti G, Caccese MC, Vennekens KM, Yates JR 3rd, and Ghosh A (2013). Unbiased discovery of glypican as a receptor for LRRTM4 in regulating excitatory synapse development. Neuron 79, 696–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J, Sylwestrak E, O’Sullivan ML, Otto S, Tiglio K, Savas JN, Yates JR 3rd, Comoletti D, Taylor P, and Ghosh A (2009). LRRTM2 interacts with Neurexin1 and regulates excitatory synapse formation. Neuron 64, 799–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Santina L, Kuo SP, Yoshimatsu T, Okawa H, Suzuki SC, Hoon M, Tsuboyama K, Rieke F, and Wong ROL (2016). Glutamatergic Monopolar Interneurons Provide a Novel Pathway of Excitation in the Mouse Retina. Curr Biol 26, 2070–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, and Lukasiewicz PD (2006). Receptor and transmitter release properties set the time course of retinal inhibition. J Neurosci 26, 9413–9425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, McCall MA, and Lukasiewicz PD (2007). Presynaptic inhibition differentially shapes transmission in distinct circuits in the mouse retina. J Physiol 582, 569–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enz R, Brandstatter JH, Wassle H, and Bormann J (1996). Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAc receptor rho subunits in the mammalian retina. J Neurosci 16, 4479–4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field GD, and Rieke F (2002). Mechanisms regulating variability of the single photon responses of mammalian rod photoreceptors. Neuron 35, 733–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher EL, Koulen P, and Wassle H (1998). GABAA and GABAC receptors on mammalian rod bipolar cells. J Comp Neurol 396, 351–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati M, Pizzarelli R, Schmidt ER, Kupferman JV, Stroebel D, Polleux F, and Charrier C (2016). SRGAP2 and Its Human-Specific Paralog Co-Regulate the Development of Excitatory and Inhibitory Synapses. Neuron 91, 356–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, and Mohler H (1995). GABAA-receptor heterogeneity in the adult rat brain: differential regional and cellular distribution of seven major subunits. J Comp Neurol 359, 154–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge Y, Kang Y, Cassidy RM, Moon KM, Lewis R, Wong ROL, Foster LJ, and Craig AM (2018). Clptm1 Limits Forward Trafficking of GABAA Receptors to Scale Inhibitory Synaptic Strength. Neuron 97, 596–610 e598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EG (1969). Electron microscopy of excitatory and inhibitory synapses: a brief review. Prog Brain Res 31, 141–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes WN, Schwartz GW, and Rieke F (2014). The synaptic and circuit mechanisms underlying a change in spatial encoding in the retina. Neuron 82, 460–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes WN, Zhang J, Graydon CW, Kachar B, and Diamond JS (2010). Retinal parallel processors: more than 100 independent microcircuits operate within a single interneuron. Neuron 65, 873–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes WN, Zhang J, Tian H, Graydon CW, Hoon M, Rieke F, and Diamond JS (2015). Complex inhibitory microcircuitry regulates retinal signaling near visual threshold. J Neurophysiol 114, 341–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JG, Koulen P, Bedford F, Gordon-Weeks PR, and Moss SJ (1999). The protein MAP-1B links GABA(C) receptors to the cytoskeleton at retinal synapses. Nature 397, 66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoon M, Krishnamoorthy V, Gollisch T, Falkenburger B, and Varoqueaux F (2017a). Loss of Neuroligin3 specifically downregulates retinal GABAAalpha2 receptors without abolishing direction selectivity. PLoS One 12, e0181011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoon M, Okawa H, Della Santina L, and Wong RO (2014). Functional architecture of the retina: development and disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 42, 44–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoon M, Sinha R, and Okawa H (2017b). Using Fluorescent Markers to Estimate Synaptic Connectivity In Situ. Methods Mol Biol 1538, 293–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoon M, Sinha R, Okawa H, Suzuki SC, Hirano AA, Brecha N, Rieke F, and Wong RO (2015). Neurotransmission plays contrasting roles in the maturation of inhibitory synapses on axons and dendrites of retinal bipolar cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 12840–12845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura Y, Suga A, Fujimaki T, Yoshitake K, Tsunoda K, Murakami A, and Iwata T (2018). LRRTM4-C538Y novel gene mutation is associated with hereditary macular degeneration with novel dysfunction of ON-type bipolar cells. J Hum Genet 63, 893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerschensteiner D, Morgan JL, Parker ED, Lewis RM, and Wong RO (2009). Neurotransmission selectively regulates synapse formation in parallel circuits in vivo. Nature 460, 1016–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J, Fuccillo MV, Malenka RC, and Sudhof TC (2009). LRRTM2 functions as a neurexin ligand in promoting excitatory synapse formation. Neuron 64, 791–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JS, Pramanik G, Um JW, Shim JS, Lee D, Kim KH, Chung GY, Condomitti G, Kim HM, Kim H, et al. (2015). PTPsigma functions as a presynaptic receptor for the glypican-4/LRRTM4 complex and is essential for excitatory synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 1874–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulen P, Brandstatter JH, Enz R, Bormann J, and Wassle H (1998). Synaptic clustering of GABA(C) receptor rho-subunits in the rat retina. Eur J Neurosci 10, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger DD, Tuffy LP, Papadopoulos T, and Brose N (2012). The role of neurexins and neuroligins in the formation, maturation, and function of vertebrate synapses. Curr Opin Neurobiol 22, 412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Lee J, and Kim E (2017). Excitation/Inhibition Imbalance in Animal Models of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Biol Psychiatry 81, 838–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhoff MW, Lauren J, Cassidy RM, Dobie FA, Takahashi H, Nygaard HB, Airaksinen MS, Strittmatter SM, and Craig AM (2009). An unbiased expression screen for synaptogenic proteins identifies the LRRTM protein family as synaptic organizers. Neuron 61, 734–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J, Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck EM, et al. (2015). Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt T, Ashery-Padan R, Andrejewski N, Scardigli R, Guillemot F, and Gruss P (2001). Pax6 is required for the multipotent state of retinal progenitor cells. Cell 105, 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meixner A, Haverkamp S, Wassle H, Fuhrer S, Thalhammer J, Kropf N, Bittner RE, Lassmann H, Wiche G, and Propst F (2000). MAP1B is required for axon guidance and Is involved in the development of the central and peripheral nervous system. J Cell Biol 151, 1169–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson JJ, Shi Y, Gujral M, Zheng H, Malhotra D, Jin X, Jian M, Liu G, Greer D, Bhandari A, et al. (2012). Whole-genome sequencing in autism identifies hot spots for de novo germline mutation. Cell 151, 1431–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monavarfeshani A, Stanton G, Van Name J, Su K, Mills WA 3rd, Swilling K, Kerr A, Huebschman NA, Su J, and Fox MA (2018). LRRTM1 underlies synaptic convergence in visual thalamus. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GJ, and Rieke F (2006). Network variability limits stimulus-evoked spike timing precision in retinal ganglion cells. Neuron 52, 511–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesch NW, and Diamond JS (2011). Ribbon synapses compute temporal contrast and encode luminance in retinal rod bipolar cells. Nat Neurosci 14, 1555–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW (2001). A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29, e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D, Pagnamenta AT, Klei L, Anney R, Merico D, Regan R, Conroy J, Magalhaes TR, Correia C, Abrahams BS, et al. (2010). Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature 466, 368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz F, Konigstorfer A, and Sudhof TC (2000). RIBEYE, a component of synaptic ribbons: a protein’s journey through evolution provides insight into synaptic ribbon function. Neuron 28, 857–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert T, Hoon M, Euler T, Lukasiewicz PD, and Wong RO (2013). Developmental regulation and activity-dependent maintenance of GABAergic presynaptic inhibition onto rod bipolar cell axonal terminals. Neuron 78, 124–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar K, Lapan SW, Whitney IE, Tran NM, Macosko EZ, Kowalczyk M, Adiconis X, Levin JZ, Nemesh J, Goldman M, et al. (2016). Comprehensive Classification of Retinal Bipolar Neurons by Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Cell 166, 1308–1323 e1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui TJ, Pancaroglu R, Kang Y, Rooyakkers A, and Craig AM (2010). LRRTMs and neuroligins bind neurexins with a differential code to cooperate in glutamate synapse development. J Neurosci 30, 7495–7506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui TJ, Tari PK, Connor SA, Zhang P, Dobie FA, She K, Kawabe H, Wang YT, Brose N, and Craig AM (2013). An LRRTM4-HSPG complex mediates excitatory synapse development on dentate gyrus granule cells. Neuron 79, 680–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Lee A, Rieke F, and Haeseleer F (2016). Lack of CaBP1/Caldendrin or CaBP2 Leads to Altered Ganglion Cell Responses. eNeuro 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler-Llavina GJ, Fuccillo MV, Ko J, Sudhof TC, and Malenka RC (2011). The neurexin ligands, neuroligins and leucine-rich repeat transmembrane proteins, perform convergent and divergent synaptic functions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 16502–16509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof TC (2017). Synaptic Neurexin Complexes: A Molecular Code for the Logic of Neural Circuits. Cell 171, 745–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof TC (2018). Towards an Understanding of Synapse Formation. Neuron 100, 276–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Katayama K, Sohya K, Miyamoto H, Prasad T, Matsumoto Y, Ota M, Yasuda H, Tsumoto T, Aruga J, and Craig AM (2012). Selective control of inhibitory synapse development by Slitrk3-PTPdelta trans-synaptic interaction. Nat Neurosci 15, 389–398, S381–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima N, Odaka YS, Sakoori K, Akagi T, Hashikawa T, Morimura N, Yamada K, and Aruga J (2011). Impaired cognitive function and altered hippocampal synapse morphology in mice lacking Lrrtm1, a gene associated with schizophrenia. PLoS One 6, e22716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terauchi A, Johnson-Venkatesh EM, Toth AB, Javed D, Sutton MA, and Umemori H (2010). Distinct FGFs promote differentiation of excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Nature 465, 783–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto Y, and Omi N (2017). Classification of Mouse Retinal Bipolar Cells: Type-Specific Connectivity with Special Reference to Rod-Driven AII Amacrine Pathways. Front Neuroanat 11, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um JW, Choi TY, Kang H, Cho YS, Choii G, Uvarov P, Park D, Jeong D, Jeon S, Lee D, et al. (2016). LRRTM3 Regulates Excitatory Synapse Development through Alternative Splicing and Neurexin Binding. Cell Rep 14, 808–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Fehlhaber KE, Sarria I, Cao Y, Ingram NT, Guerrero-Given D, Throesch B, Baldwin K, Kamasawa N, Ohtsuka T, et al. (2017). The Auxiliary Calcium Channel Subunit alpha2delta4 Is Required for Axonal Elaboration, Synaptic Transmission, and Wiring of Rod Photoreceptors. Neuron 93, 1359–1374 e1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassle H (2004). Parallel processing in the mammalian retina. Nat Rev Neurosci 5, 747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SM, Mountjoy E, Muir D, Ross SE, and Atan D (2018). A comparative analysis of rod bipolar cell transcriptomes identifies novel genes implicated in night vision. Sci Rep 8, 5506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata A, Goto-Ito S, Sato Y, Shiroshima T, Maeda A, Watanabe M, Saitoh T, Maenaka K, Terada T, Yoshida T, et al. (2018). Structural insights into modulation and selectivity of transsynaptic neurexin-LRRTM interaction. Nat Commun 9, 3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata M, Sanes JR, and Weiner JA (2003). Synaptic adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Cell Biol 15, 621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim YS, Kwon Y, Nam J, Yoon HI, Lee K, Kim DG, Kim E, Kim CH, and Ko J (2013). Slitrks control excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation with LAR receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 4057–4062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Atasoy D, Arac D, Yang X, Fucillo MV, Robison AJ, Ko J, Brunger AT, and Sudhof TC (2010). Neurexins physically and functionally interact with GABA(A) receptors. Neuron 66, 403–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Lu H, Peixoto RT, Pines MK, Ge Y, Oku S, Siddiqui TJ, Xie Y, Wu W, Archer-Hartmann S, et al. (2018). Heparan Sulfate Organizes Neuronal Synapses through Neurexin Partnerships. Cell 174, 1450–1464 e1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the current study have not been deposited in a public repository because of extremely large file sizes but are available from the corresponding author on request.