Abstract

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, US federal and state governments have implemented wide-ranging stay-at-home recommendations as a means to reduce spread of infection. As a consequence, many US healthcare systems and practices have curtailed ambulatory clinic visits—pillars of care for patients with heart failure (HF). In this context, synchronous audio/video interactions, also known as virtual visits (VVs), have emerged as an innovative and necessary alternative. This scientific statement outlines the benefits and challenges of VVs, enumerates changes in policy and reimbursement that have increased the feasibility of VVs during the COVID-19 era, describes platforms and models of care for VVs, and provides a vision for the future of VVs.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly contagious disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The COVID-19 pandemic presents an unprecedented crisis for patients, clinicians and health care systems in the United States (US). In response, US federal and state governments have implemented wide-ranging stay-at-home recommendations as a means of reducing spread and have ordered nonessential businesses to close temporarily. At the time of this writing, social distancing is the only known way to mitigate the continued spread of COVID-19 because there is currently no proven vaccine or treatment. In an effort to reduce patients’ exposure and transmission of disease, to conserve supplies and to maximize personnel that are needed to provide care to the large number of people with severe COVID-19 cases requiring hospitalization, many US health care systems have reduced ambulatory outpatient clinics—pillars of the longitudinal care of patients with chronic illnesses such as heart failure (HF). In this context, synchronous audio/video interactions, also known as virtual visits (VVs), have been suggested as innovative and necessary alternatives to in-person care.

VVs provide a platform for real-time interactive telehealth interactions between patients and clinicians using commonly available home-consumer devices. Early adopters of VVs have described their feasibility, potential to save time and cost and patient satisfaction related to increased access to care and the convenience of avoiding trips to the office.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been a leader in the use of telehealth. In fiscal year 2019, more than 99,000 veterans used the VA Video Connect app at their homes, resulting in 294,000 virtual appointments.6 Although the majority of these visits were for mental health, the VA experience demonstrates the feasibility of broadly using VVs to provide care for chronic illness.

The value of VVs was recently demonstrated in a randomized clinical trial evaluating VVs vs in-person ambulatory visits in the postdischarge care of patients with heart failure (HF) (Virtual Visits in Heart Failure Care Transitions; NCT03675828; Late Breaking Clinical Trial presentation at the Heart Failure of Society of America's Annual Scientific Meeting 2019 in Philadelphia, PA). The aims of this pilot study were to test the feasibility and safety of substituting in-person visits with VVs for patients (N = 108) transitioning from hospital to home after hospitalization for HF and to assess to what degree VVs can reduce appointment no-show rates. The no-show rate in the VV arm trended lower than the observed rate in the in-person arm (VV 34.6% vs in-person arm 50%; RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.44–1.09; P = 0.12) without any signal of harm—no significant differences in hospital readmissions, emergency department visits or death between the study arms.7 Yet, despite its promise, wide use of VVs in the US health care environment prior to the COVID-19 pandemic has been limited due to lack of familiarity with the technologies by both clinicians and patients, concerns about the safety of substituting in-person visits with VVs, lack of integration into clinicians’ established workflows, perceived and actual legal barriers, and limited payer reimbursement.8

In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of these barriers have now disappeared, given the importance of social distancing. The purpose of this article is to provide a pragmatic guide to HF clinicians about provision of VVs in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. First, we outline benefits and value of VVs, some of the clinical challenges and the recent COVID-19–related changes in policy and reimbursement that have facilitated the uptake of VVs. Then we outline some of the VV platforms that currently exist and describe models of care using VVs. Finally, we describe the short-term and long-term future implications of VVs.

Benefits and Value of Virtual Visits

During the current public health emergency, VVs have multiple potential benefits (Table 1 ). From patients’ standpoint, VVs provide access to care when it has been significantly curtailed or entirely disappeared. By providing a platform for patients to continue to receive medical advice and instruction regarding their medical conditions, VVs have become integral to optimizing health for patients and reducing related distress while reducing in-person exposure. Given current restrictions on accompaniment during visits to medical facilities, VVs have additionally facilitated involvement by patients’ caregivers, who are often so critically important in many of the self-care practices necessary for adults with HF.9 Some patients may find it easier to discuss difficult topics while in the comfort of their homes and with family members who may not otherwise be present for in-person visits. From clinicians’ standpoint, VVs permit them to continue to serve their patients from the safety of their own homes, through provision of care to their medically complex patients. The ability to have a face-to-face encounter may be especially valuable in preserving patient-physician trust in the absence of in-person visits. From a health care systems standpoint, provision of services remotely has allowed reallocation of resources to focus on inpatient services, which are at risk of becoming overwhelmed and saturated, given the rapidity and volume of severe COVID-19 cases requiring acute inpatient care. Additionally, VVs allow continued delivery of services with reimbursement that can contribute to ensuring the financial sustainability of hospitals, practices and the US health care system as a whole. Finally, VVs can be leveraged toward ensuring continuation of research studies, where patient contact is necessary for data collection, as well as ensuring the safety of human subjects.

Table 1.

Benefits and Value of Virtual Visits

| Group | Potential benefits |

|---|---|

| Patient | • Provide access |

| • Receive medical advice | |

| • Reduce in-person exposure to SARS-CoV-2 | |

| • Reduce distress | |

| • Involve caregivers | |

| Clinician | • Serve patients |

| • Reduce in-person exposure to SARS-CoV-2 | |

| • Maintain connection between patient and provider | |

| Health care systems | • Reallocate resources |

| • Generate revenue | |

| • Support research efforts |

Challenges to Virtual Care

To conduct a VV successfully, patients must be willing and able, and the technology must be available and effective. Accordingly, VVs may present some challenges in selected circumstances. Some patients may be reluctant to participate in VVs because they feel uncomfortable with technology or feel self-conscious about interacting on video. These feelings may become less common as VVs enter the mainstream. VVs present a barrier to performing a full physical examination, though many components of a partial examination can be completed, and existing and emerging diagnostic technologies and wearables may fill in the gaps. This is discussed further below. Some clinicians and patients may feel that even with the use of video, VVs are not the same as in-person visits with respect to patient-physician interactions; something is lost without close proximity and the “laying-on of hands.” Some patients may have limited access to the internet, and/or may not have a computer or smart device to engage in VVs, including the poor and elderly in inner city and rural areas. Although there may be geographic and financial challenges to obtaining WiFi for some patients, we anticipate that future technology will provide hotspots via ubiquitous cellular networks, thus alleviating most barriers to internet access. Some health care systems are investing in these technologies and providing equipment and connectivity to ensure that telehealth does not widen health disparities.10 , 11

Older adults may be viewed as a subpopulation in which these challenges are common. This is particularly important because more than half of patients currently living with HF in the US are older than 70 years.12 However, recent data show that an increasing number of older adults possess smartphones and that some guidance to using newer technology can be taught, possibly by hospital/clinic support teams.13 Integration of the VVs technology platform within an institution's electronic portal or app, which is already familiar to patients, may be another approach to overcoming these challenges.

Patients and clinicians may occasionally encounter technical difficulties when conducting VVs. These may include an inability to initiate the VV, connectivity issues and/or audio/video problems. Some of this may be a direct result of larger than anticipated volumes of users concurrently attempting to use a platform in the setting of the COVID-19 crisis. Over time, the hope is that software upgrades will address these issues and that platforms will be able to accommodate a greater number of users. Of note, if and when these technical issues arise, switching to a telephone visit is a reasonable solution and remains reimbursable.

Policy Changes That Increase the Feasibility of Virtual Visits in the Era of COVID-19

Several governing bodies, including the US Executive Branch, US Congress, US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and state governments, have relaxed rules and regulations that have subsequently increased the feasibility of VVs. In response to the ongoing COVID-19 public health emergency the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, was passed with near unanimous support by the US Congress and was signed into law by the President on March 6, 2020.14 This bill allowed HHS to “temporarily waive certain Medicare restrictions and requirements regarding telehealth services during the coronavirus public health emergency.” Then on March 13, 2020, the President proclaimed the COVID-19 outbreak a US national emergency, which allowed HHS to exercise its authority under section 1135 of the Social Security Act to temporarily waive certain requirements of Medicare, Medicaid and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996.15 Specific steps taken by HHS and states are described below, and a summary of key policy changes are shown in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Telehealth-related Policy Changes in the Era of COVID-19

| Topic | Key policy changes: COVID-19 pandemic | Implications for virtual visits |

|---|---|---|

| Licensing | HHS waived requirement for health care professionals to hold license in state in which they provide services if they have an equivalent license from another state. HHS asked states to waive local licensing requirements, with final decision made at state level. | Potentially allows practice of medicine via virtual visits across state lines. |

| Privacy | HHS suspended HIPAA rules. | Allows use of virtual visit platforms previously deemed not HIPAA-compliant. |

| Location of patient | CMS waived rural and site limitations for telehealth interactions. | Allows clinicians to be reimbursed for telehealth services regardless of patients’ locations. |

| Prior existing relationship | CMS waived requirement that telehealth services can be provided only to a clinician's established patients. | Clinicians can see new patients by telehealth. |

| Prescription | DEA relaxed rules related to prescription of controlled substances by telehealth. | Clinicians can prescribe controlled-substances in setting of a virtual visit. |

CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; DEA, Drug Enforcement Administration; HHS, US Department of Health & Human Services; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

HHS has eased a variety of rules that relate to medical licensing and privacy, which directly affect telehealth practice. First, the requirements that both physicians and other health care professionals hold licenses in the state in which they provide services were waived by the federal government.16 Second, HIPAA privacy rules were suspended. Specifically, HHS indicated that it will “exercise its enforcement discretion and will not impose penalties for noncompliance” with HIPAA rules as they relate to both telehealth technologies and the manner in which they are used.17 This is important because clinicians are now allowed to deliver medical care via any nonpublic VV platform, even if not previously deemed HIPAA-compliant. In the short term, this increased flexibility may lead to increased uptake of VVs. In the long term, we recommend that HF clinicians use HIPAA-compliant platforms whenever possible, both for extra security and to develop practices and habits that will be relevant in postpandemic settings.

States have individually taken a variety of steps to remove barriers to VVs in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. These relate to Medicaid reimbursement, licensing and home eligibility site. The Center for Connected Health Policy is maintaining a comprehensive state-specific summary of these steps, which can be found on its website (https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-related-state-actions).

Recent Changes in Reimbursement for Virtual Visits

Reimbursement for VVs was limited prior to the COVID-19 public health emergency. With just a few exceptions, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reimbursed for telehealth visits only in specific circumstances: patients had to have an established relationship with their physician, had to live in a rural area, and had to be located in a medical facility at the time of the VV (“originating site”). Many commercial insurance providers reimbursed urgent-care VVs (ie, substitution of in-person emergency department or urgent-care visits), with only a small number reimbursing for primary care or specialty care VVs. Meanwhile, some hospitals have started offering VVs in selected settings for certain high-risk conditions (including HF), spending institutional resources in the hope that long-term savings through bundled-payment models would ultimately compensate for the associated costs of VVs, whereas others have offered VVs in exchange for direct cash payment from patients.

In March 2020, following the announcement of the COVID-19 public health emergency and the 1135 Waiver, several important telehealth-related reimbursement changes occurred. CMS announced that VVs, referred to as “telehealth visits” in CMS documents, would be reimbursed at the same rate as in-person visits during the COVID-19 crisis, without limits on the purposes of the visits, the geographic locations of patients or whether there was a previously established relationship with the provider. Multiple commercial insurance providers, including Aetna, Cigna, Humana, and Blue Cross Blue Shield, among others, have followed suit. Waivers of beneficiary copays for these telehealth services vary among these providers.

To secure reimbursement at the current time, documentation for VVs should approximate documentation for in-person ambulatory clinic visits. We recommend that clinicians explicitly document that a virtual (audio/video) visit was completed, with the patient's consent. Clinicians should document the amount of time it took to conduct the visit in minutes. Specific Current Procedural Terminology billing codes and relevant modifiers are shown in Table 3 . The future state of Electronic Health Record documentation for VVs may include the capture of images or streaming clips of video interactions, automated transcription of key components of the conversation and the use of natural language processing to determine meaning and summarize information.

Table 3.

Billing Codes for Virtual Visits (Also Called “Telehealth visits” by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services)

| Description | Code and Modifier |

|---|---|

| Office or other outpatient visit for the evaluation and management of a new patient | CPT Code 99201-99205* |

| Place of service 02 for Telehealth (Medicare), or, | |

| Modifier GT (Medicare/Medicaid) | |

| Modifier 95 (Commercial payers) | |

| Office or other outpatient visit for the evaluation and management of an established patient | CPT Code 99211–99215* |

| Place of service 02 for Telehealth (Medicare) or | |

| Modifier GT (Medicare/Medicaid) | |

| Modifier 95 (Commercial payers) | |

| Telehealth consultations, emergency department or initial inpatient | G0425–G0427 |

| Follow-up inpatient telehealth consultations furnished to beneficiaries in hospitals or skilled nursing facilities | G0406–G0408 |

Choice of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code depends on whether the provider elects to use time-based coding vs component-based coding. For example, a provider using time-based coding for a Medicare beneficiary seen by VV for 15 minutes would document the time spent in the note and then may choose CPT code 99213 with modifier GT, if otherwise appropriate for that encounter.

Virtual Visit Platforms

According to HHS, “a covered health care provider that wants to use audio or video communication technology to provide telehealth to patients during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency can use any non-public facing remote communication product that is available to communicate with patients.” Non-public facing products are typically platforms that employ end-to-end encryption and that allow only an individual and the person with whom the individual is communicating to see what is transmitted. On the other hand, public-facing platforms (ie, Facebook Live, Twitch, and TikTok) are designed to be open to the public or to allow wide or indiscriminate access to the communication. Table 4 outlines and describes some common platforms that may be used for VVs.

Table 4.

Virtual Visit Platforms Used During COVID-19 Public Health Emergency

| Name | Notes | |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer apps | Apple FaceTime Facebook Messenger video chat Google Hangouts video Zoom Skype |

|

| Specialized technology platforms | Skype for Business/Microsoft Teams Updox VSee Zoom for Healthcare Doxy.me Google G Suite Hangouts Meet Cisco Webex Meetings / Webex Teams Amazon Chime GoToMeeting Spruce Health Care Messenger American Well MDLive BlueJeans for Healthcare Doximity |

|

HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Virtual Visit Models of Care

Which patients should be seen by virtual visits?

VVs can be used to evaluate the full range of patients with HF, including those with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, across all stages of HF (A-D), including those with left ventricular assist devices and heart transplant recipients. Clinical assessment provided over VVs can include evaluation of clinical status, medication review and management, screening for adverse events, uptitration of guideline-directed therapy, and counseling about topics related to medication adherence, diet and exercise.

In general, outpatient visits may be classified as urgent or routine. The urgent classification includes visits for new or worsening HF symptoms or visits applicable to patients with recent left ventricular assist device implantation or heart transplantation. Using VVs to manage and triage complaints of dyspnea may be especially important during the COVID-19 crisis, given the importance of differentiating worsening HF from acute COVID-19 that could very rapidly deteriorate to respiratory failure. Individuals who are nearing stage D HF and those requiring inotropes may also be important priorities because of their potential to decompensate. Routine visits could include those focused on medication titration, new test results or time-interval associated visits. Many HF programs across the country have already converted in-person visits into VVs, keeping patients in the same previously scheduled dates and time slots.

Both urgent and routine visits may be conducted via VVs, depending on resource availability. An algorithm that clearly differentiates urgent from routine visits may be helpful for allocating resources. Administrative personnel and nurses should be trained to triage effectively according to each practice's preferences. Clinicians may also use VVs to screen urgent complaints and decide which patients need to be seen in-person.

Importantly, a variety of HF clinicians, including physicians, advanced practice providers and licensed social workers, can perform and be reimbursed for VVs.18 Pharmacists can provide VVs as well, but billing would have to occur through the supervising physician.19 Clinicians who require quarantine but are well enough to practice may provide an additional workforce to conduct VVs while their in-person contributions are limited. Although it is preferred that VVs occur between the patient and the usual HF clinician and team, it may be necessary in some cases for clinicians to conduct VVs with colleagues’ patients; this will likely vary across health care systems.

What is the clinical workflow of a clinicor office practice performing telehealth virtual visits?

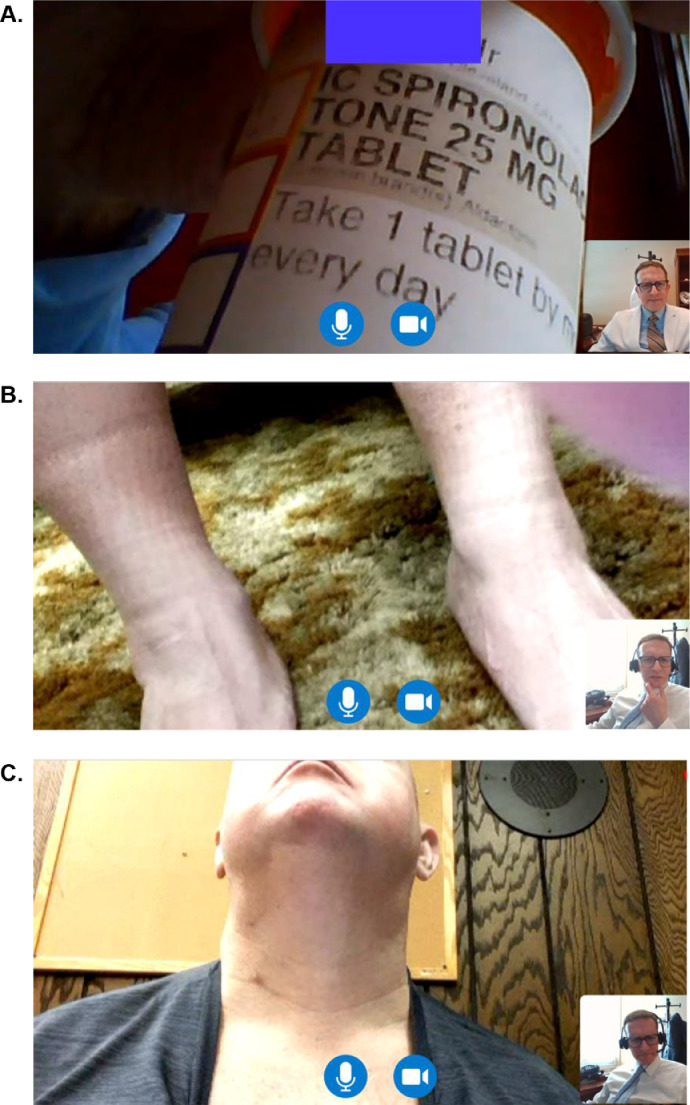

VVs can be engineered to approximate traditional in-person visits (Table 5 ). During these visits, various personnel can obtain a history, conduct a medication reconciliation, review allergies, perform a review of systems, and subsequently document patient-reported vital signs. Leveraging VVs toward medication review by video (Fig. 1 ) is particularly appealing, given the number of medications that patients with HF take and the associated risk for medication errors and adverse drug events.20 To do this, clinicians can ask patients to hold pill bottles up to the camera for the clinician to visualize and review. VVs might actually be superior to a usual in-person clinic visit in this regard, because pill bottles are infrequently taken to in-person appointments.

Table 5.

Preparations for a Successful Virtual Visit

| Before the VV | • Determine which platform and technology will be used for the VV, and ensure that your patient can engage. |

| • Ensure that the patient has consented to VV (verbal or written). | |

| • Position yourself centered in front of your webcam, smartphone or tablet. Adjust lighting in the room. | |

| • Confirm that video and audio are functioning appropriately. | |

| • Consider having your EHR open for live review during the VV, either on another screen or using a split-screen configuration. | |

| • Follow VV etiquette: conduct visit in a private professional-appearing space, make sure there are no background noises or distractions, mute your audio connection when not speaking. | |

| • Collaborate with support staff who may contact patients in advance to obtain vital signs, perform medication review and confirm time the clinician will call. This will vary by practice. | |

| During the VV | • Confirm that patient's audio and video connections are established. |

| • Maintain visual eye contact. | |

| • Ensure patient's readiness to begin. If distractions are noted, ask to minimize them. | |

| • Determine whether this is their first experience with VV and acknowledge uneasiness, if any. Let the patient know he or she can interrupt at any time if there are issues with the platform or the visit in any way. | |

| • Guide the patient through maneuvering the camera for a physical examination. | |

| • Address a need for laboratory studies. | |

| • Use teach-back, and ask the patient to write down important instructions, medication changes and follow-up plan. Reinforce usual self-care. | |

| • End the visit by asking the patient how the experience was, what worked well, what could be better, and use this information for planning future visits. | |

| After the VV | • Document in the EHR: VV performed with a VV attestation and time spent, nature of the visit and who was present. Consider a specific designation for the note (eg, Heart Failure Virtual Visit). |

| • E-mail, mail or message patient about any medication updates or specific instructions for care. | |

| • Arrange for laboratory testing, if needed. | |

| • Bill for the encounter. | |

| • Plan for the next visit. |

EHR, Electronic Health Record; VV, virtual visit.

Fig. 1.

Screen shots from video virtual visits between an HF cardiologist (right lower corner) and a patient. (A) Medication review by video. (B) Examination of ankles showing sock markings without edema. (C) Neck examination.

Basic components of the physical examination can be performed via telehealth, especially when patients use high-quality video equipment available on contemporary smartphones and tablets (Fig. 1). These components may include general appearance, including alertness and orientation, as well as an assessment of volume status by looking for signs of peripheral edema such as leg swelling and remote evaluation of neck veins. Assessment of neck veins is best done with a second person moving the camera position relative to the patient's neck in order to obtain the appropriate angle and lighting. Recent data have demonstrated that assessment of neck veins with video magnification technology correlates with invasively measured right atrial pressure.21 Assessment of orthopnea and bendopnea may also be done remotely, both of which are associated with elevated ventricular filling pressures.22 , 23 VVs may also permit an assessment of exercise intolerance, for example by asking the patient to walk from room to room or up a flight of stairs. Finally, it is possible to use VVs to examine peripherally inserted central catheter line sites and other cannulas, as well as healing surgical incisions such as pacemaker or implantable cardiac defibrillator implantation sites.

Adjuncts to virtual visits

Several remote monitoring capabilities are already in use for the care of patients with HF and can complement data collected during VVs.24 The most basic is remote monitoring of weight and blood pressure via electronic scales and blood pressure cuffs. CardioMEMS, a hemodynamic monitor implanted into the pulmonary artery, remotely transmits pulmonary artery pressures and has been shown to reduce hospital readmissions and improve quality of life; thus, it may be used in addition to telehealth visits to guide therapy.25 , 26 Similarly, remote interrogation concerning implantable cardiac defibrillators to assess arrhythmia burden can provide additional information. Whether wearable devices for ambulatory cardiac monitoring, such as wristwatches, smartphones, patches, headbands, eyeglasses, necklaces, or vests, can be integrated into clinical management provided through VVs is unknown and warrants future investigation.27, 28, 29

Advance care planning

VVs provide a unique opportunity to engage patients and caregivers on topics related to advance care planning, which are of heightened importance during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among higher risk populations. Conducting these conversations while the patient (and their caregivers) are in the comfort of their own homes may provide the optimal setting for these discussions. As the COVID-19 crisis unfolds, issues related to becoming acutely ill may very well be on the minds of many patients with HF. Accordingly, it may be appropriate to discuss care preferences during VVs. Questions that may be routinely incorporated into the discussion include:

-

•

Have you appointed a health care proxy? This is a person who would make decisions on your behalf if you were unable to make decisions.

-

•

Have you completed an advance directive form?

-

•

Does your health care proxy and/or family know what your care preferences would be if you were to get sick and could not make decisions for yourself?

-

•

Do you have a health care power of attorney form? This is a legal document that gives 1 person the authority to make health care decisions for you if you are unable to do so.

Pharmacy considerations following a virtual visit

One of the major goals of VVs is to reduce exposure to others who potentially could be infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Consistent with this goal, it is equally important to consider patients’ strategies for obtaining medications that permit social distancing. Delivery of medications to the patients’ homes is 1 method to reduce exposure. Approximately 20% of patients historically use mail-delivery pharmacy services, which means the majority of the population will have to navigate this process for the first time during the current public health crisis.30 National mail-delivery pharmacies may be a long-term solution for many patients, but new patients and prescriptions will typically experience a 1–2 week delay before delivery. It may be prudent, then, to use independent and chain pharmacies, many of which can deliver medications within their communities on the same or the next day. Of note, various pharmacy chains have waived delivery fees during the COVID-19 crisis. For patients unwilling or unable to use these services, selecting a pharmacy location with a drive-up window may provide an alternative solution that permits some degree of social distancing.

Clinicians should consider prescribing 90-day supplies when appropriate and helping patients synchronize all medication refills to a common schedule to reduce the number of trips to a pharmacy; especially now that many of the traditional legal and administrative barriers to these efforts have been removed for COVID-19. Both CMS Part D sponsors and commercial pharmacy benefit managers have relaxed restrictions on early refills and now allow the maximum daily supply (most commonly 90 days) for medications to be filled. Additionally, many states have instituted emergency actions to facilitate medication access, such as allowing pharmacies to dispense an emergency 30-day supply of chronic, noncontrolled medications when patients are awaiting refill authorization from providers. A continually updated list of pharmacy-related state actions impacting medication access sorted by state is available at the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations website (https://naspa.us/resource/covid-19-information-from-the-states).

Inpatient use of telehealth

Although this article is focused primarily on leveraging VVs for continued ambulatory care of adults with HF, these principles also apply to the inpatient setting. Given concerns about shortages in personal protective equipment, VVs may be beneficial to clinicians working in the inpatient setting and have already been implemented by some health care systems across the US. Approaches vary, but they most commonly involve the use of either hospital-provided or the patient's own smartphone or tablet. Software platforms reportedly being used include Apple FaceTime, Cisco Jabber and Microsoft Team, among others; some of them allow multiple team members to connect and conduct virtual rounds together. These visits may be enriched by the use of Bluetooth stethoscopes and point-of-care ultrasound technology that can provide valuable information about the physical examination while limiting exposure. Of note, VVs for inpatient care are reimbursable (Table 3) and are equivalent to in-person hospital service. If the consultant is outside of the hospital and the patient is in the hospital, these inpatient encounters can be billed as an ambulatory telehealth visit.

Future of virtual visits after resolution of the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 has saturated some hospitals with high volumes of patients with respiratory syndromes and respiratory failure, and, subsequently, has forced the medical community to rely on VVs to provide routine care to many patients with chronic medical illnesses such as HF. Importantly, survivors will likely require prolonged time for recovery, and it remains unclear where these patients will recover and rehabilitate. At the present time, many rehabilitation and long-term care facilities do not accept patients who were COVID-19-positive because of concerns about disease transmission. It is, therefore, possible that some US hospitals will remain at capacity well beyond the time period of the COVID-19 surge. Additionally, emerging data suggest that at least 20% of COVID-19-positive patients are health care providers, which will stretch the active work force even further. Thus, continuing resource-efficient strategies like VVs may be necessary for the near and intermediate future.

It is unclear what the psychological impact of COVID-19 will be on providers and patients, especially those patients who are at highest risk—including those with chronic conditions such as HF. An important consideration is that even after the COVID-19 crisis ends, patients may continue to have concerns about in-person office visits and travel and may prefer to continue with a degree of social distancing. As a result, many patients with HF may continue to prefer VVs. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was little impetus for clinicians to learn or embrace VVs. In the current era, many clinicians have been forced to learn and use VVs. Consequently, as we move beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, clinicians may be more amenable to VVs; in fact, some may even prefer them.

With these expectations in mind we believe that VV models of care will become the norm in the US health care system as we move forward, especially for patients with HF. Many patients with HF, especially older adults with disabilities and those living in rural communities often have difficulty attending in-person visits due to very poor exercise tolerance, inadequate transportation and difficulty in transporting oxgyen, among other barriers. For these patients, VVs are certainly more convenient; likewise for their caregivers, who sometimes have to take time off from work to take their family member to the appointment.

Policy and reimbursement practices developed in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency and discussed in this article may remain and further evolve to accommodate continued use of VVs. We suspect that it is possible, if not likely, that CMS will continue incentivizing VVs, though likely at lower reimbursement rates than in-person visits. Distant health technologies that align with VVs, including biosensing wearables28 , 31 and other diagnostic tools, may be increasingly adopted. Whether the use of VVs can improve adherence, decrease no-show rates, decrease office overhead, improve transitions of care from the inpatient to outpatient setting, or prevent emergency department visits and hospital admissions and readmissions for patients with HF is yet unknown. This underscores the need to collect outcomes data. Although frightening to consider, we will be better able to pivot when the next pandemic comes along when we have VV systems in place. Regardless, the COVID-19 pandemic has generated an important opportunity to learn about delivering HF care in a different way, a way that should be fully embraced well beyond the current crisis.

Disclosures

No relevant conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

See page 455 for disclosure information.

References

- 1.White T., Watts P., Morris M., Moss J. Virtual postoperative visits for new ostomates. Comput Inform Nurs. 2019;37:73–79. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tasneem S., Kim A., Bagheri A., Lebret J. Telemedicine video visits for patients receiving palliative care: a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36:789–794. doi: 10.1177/1049909119846843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nord G., Rising K.L., Band R.A., Carr B.G., Hollander J.E. On-demand synchronous audio video telemedicine visits are cost-effective. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37:890–894. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crossen S., Glaser N., Sauers-Ford H., Chen S., Tran V., Marcin J. Home-based video visits for pediatric patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. J Telemed Telecare. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1357633X19828173. 1357633X19828173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiyagarajan A., Grant C., Griffiths F., Atherton H. Exploring patients’ and clinicians’ experiences of video consultations in primary care: a systematic scoping review. BJGP Open. 2020 doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.VA reports significant increase in Veteran use of telehealth services. Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. https://www.va.gov/opa/pressrel/pressrelease.cfm?id=5365. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- 7.Gorodeski E.Z., Moennich L.A., Riaz H., Tang W.H.W. Virtual visits versus in-person visits and appointment no-show rates. J Card Fail. 2019;25:939. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraiche A.M., Eapen Z.J., McClellan M.B. Moving beyond the walls of the clinic: opportunities and challenges to the future of telehealth in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riegel B., Lee C.S., Dickson V.V. Self-care in patients with chronic heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:644–654. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.deShazo R.D., Parker S.B. Lessonslearned from Mississippi's telehealth approach to health disparities. Am J Med. 2017;130:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker J., Stanley A. Telemedicine technology: a review of services, equipment, and other aspects. Curr Allerg Asth Rep. 2018;18:60. doi: 10.1007/s11882-018-0814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorodeski E.Z., Goyal P., Hummel S.L., Krishnaswami A., Goodlin S.J., Hart L.L., Geriatric Cardiology Section Leadership Council, ACoC Domain management approach to heart failure in the geriatric patient: present and future. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:1921–1936. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson M., Perrin A. Pew Research Center; May 17, 2017. Tech adoption climbs among older adults.http://www.pewinternet.org/2017/05/17/tech-adoption-climbs-among-older-adults/pi_2017-05-17_older-americans-tech_1-03/ Accessed April 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coronavirus preparedness and response supplemental appropriations act, H.R.6074, 116th Cong. (2019-2020). https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6074/text. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- 15.Trump D.J. Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. The White House; March 13, 2020. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak Accessed April 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azar A.M. US Department of Health & Human Services; March 13, 2020. Waiver or modification of requirements under Section 1135 of the Social Security Act.https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions/section1135/Pages/covid19-13March20.aspx Accessed April 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Deparment of Health & Human Services; March 17, 2020. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the covid-19 nationwide public health emergency.https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html Accessed April 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. March 17, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- 19.Physicians and other clinicians: CMS flexibilities to fight COVID-19. March 30, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-19-physicians-and-practitioners.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2020.

- 20.Goyal P., Bryan J., Kneifati-Hayek J., Sterling M.R., Banerjee S., Maurer M.S. Association between functional impairment and medication burden in adults with heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:284–291. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abnousi F., Kang G., Giacomini J., Yeung A., Zarafshar S., Vesom N. A novel noninvasive method for remote heart failure monitoring: the EuleriAn video Magnification apPLications In heart Failure studY (AMPLIFY) NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2:80. doi: 10.1038/s41746-019-0159-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thibodeau J.T., Turer A.T., Gualano S.K., Ayers C.R., Velez-Martinez M., Mishkin J.D. Characterization of a novel symptom of advanced heart failure: bendopnea. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drazner M.H., Hellkamp A.S., Leier C.V., Shah M.R., Miller L.W., Russell S.D. Value of clinician assessment of hemodynamics in advanced heart failure: the ESCAPE trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2008;1:170–177. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.769778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickinson M.G., Allen L.A., Albert N.A., DiSalvo T., Ewald G.A., Vest A.R. Remote monitoring of patients with heart failure: a white paper from the Heart Failure Society of America Scientific Statements Committee. J Card Fail. 2018;24:682–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adamson P.B., Abraham W.T., Bourge R.C., Costanzo M.R., Hasan A., Yadav C. Wireless pulmonary artery pressure monitoring guides management to reduce decompensation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:935–944. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.001229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heywood J.T., Jermyn R., Shavelle D., Abraham W.T., Bhimaraj A., Bhatt K. Impact of practice-based management of pulmonary artery pressures in 2000 patients implanted with the CardioMEMS sensor. Circulation. 2017;135:1509–1517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez M.V., Mahaffey K.W., Hedlin H., Rumsfeld J.S., Garcia A., Ferris T. Apple Heart Study I. Large-scale assessment of a Smartwatch to identify atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1909–1917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sana F., Isselbacher E.M., Singh J.P., Heist E.K., Pathik B., Armoundas A.A. Wearable devices for ambulatory cardiac monitoring: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1582–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham W.T., Anker S., Burkhoff D., Cleland J., Gorodeski E., Jaarsma T. Primary results of the Sensible Medical Innovations Lung Fluid Status Monitor allows reducing readmission rate of heart failure patients (SMILE) trial. J Card Fail. 2019;25:938. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma J., Wang L. Characteristics of mail-order pharmacy users: results from the Medical Expenditures Panel survey. J Pharm Pract. 2018 doi: 10.1177/0897190018800188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeVore A.D., Wosik J., Hernandez A.F. The future of wearables in heart failure patients. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7:922–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]