Abstract

Background:

Alcohol expectancies, or the perceived likelihood of experiencing certain effects after consuming alcohol, are associated with college student drinking such that heavier drinkers expect a greater likelihood of positive effects. However, less is known as to whether day-to-day within-person deviations in expectancies are associated with drinking that same day and for whom and when these associations may be strongest.

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to examine daily-level associations of positive and negative alcohol expectancies with alcohol use, and whether associations differed according to demographic characteristics and additional alcohol-related constructs.

Methods:

College student drinkers (N = 327, 53.8% female) participated in an intensive longitudinal study that captured daily-level data. Alcohol use and expectancy measures were utilized from a baseline session and at the daily-level using Interactive Voice Response (IVR).

Results:

Results found that on days when participants reported stronger positive and negative expectancies than their average, they were more likely to drink as well as consume more alcohol when drinking. Moderation analyses revealed that positive expectancies were more positively associated with the likelihood of any drinking for women relative to men, and more positively associated with the quantity of alcohol consumption for younger students, students with lower baseline rates of drinking, and students with greater overall positive alcohol expectancies.

Conclusions/Importance:

The findings demonstrate that alcohol expectancies fluctuate within-person across days and these fluctuations are meaningful in predicting same-day drinking. Interventions that seek to modify expectancies proximal to drinking events may be considered to reduce college student drinking.

Keywords: Alcohol, Expectancies, College, Longitudinal, Moderation

Introduction

Considerable research has shown that late adolescence and early young adulthood are associated with increased risk of alcohol misuse and alcohol use disorders (Brown et al., 2008; Patrick & Schulenberg, 2011; Schulenberg et al., 2019). This period of time is characterized by increased binge drinking (five or more drinks in a row) and high-intensity drinking (ten or more drinks in a row), with prevalence peaking in young adulthood (ages 21-22), and greater peaks for US college students as compared to non-college attending peers (Patrick, Terry-McElrath, Kloska, & Schulenberg, 2016b). College students in particular are at increased risk for experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences. Heavier drinking in college students is associated with vandalism, poor class attendance and academic performance, memory blackouts, hangovers, trouble with authorities, injuries, sexual assaults, and fatalities (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009; White & Hingson, 2013).

Despite these widespread reports of negative drinking consequences, many college students maintain high levels of alcohol consumption. Further, many college students do not feel the need to reduce their drinking behavior (Steinman, 2003) and report alcohol-related consequences as a defining characteristic of the college experience (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002). One potential explanation for this phenomenon is that college students also report myriad positive effects from alcohol (Barnett et al., 2014; Fairlie, Ramirez, Patrick, & Lee, 2016). Additionally, as compared to negative consequences, positive consequences tend to occur more frequently (Lee, Maggs, Neighbors, & Patrick, 2011; Park, 2004), and tend to be more immediate following alcohol consumption.

Alcohol expectancy theory (Goldman, Brown, & Christiansen, 1987; Goldman, Del Boca, & Darkes, 1999) is an extension of social learning models (e.g., Bandura, 1977) and provides a framework to examine how drinking behavior is influenced by both positive and negative consequences and the expectancies that arise from these experiences. Alcohol outcome expectancies are perceptions of the likelihood of experiencing certain effects as an outcome of alcohol use (Fromme, Stroot, & Kaplan, 1993). These expectancies often form as a result of learned experiences and can be either positive or negative. Alcohol expectancy theory posits that expecting positive effects should increase drinking behavior, whereas expecting negative effects should decrease drinking behavior (Goldman et al., 1987; 1999). In support of this model, research has demonstrated that positive alcohol expectancies are associated with greater college student alcohol use both concurrently (Fromme et al., 1993; Ham, Stewart, Norton, & Hope, 2005; Patrick, Cronce, Fairlie, Atkins, & Lee, 2016a; Zamboanga, 2006), and prospectively (Zamboanga, Horton, Leitkowski, & Wang, 2006).

Findings regarding negative expectancies have been less consistent. In support of alcohol expectancy theory, some cross-sectional studies have found that stronger negative expectancies are associated with less college student drinking (Nicolai, Demmel, & Moshagen, 2010). In contrast, other cross-sectional studies have demonstrated positive associations between negative expectancies and hazardous alcohol use (Zamboanga, Schwartz, Ham, Borsari, & Van Tyne, 2010), and some have found no relationship between negative expectancies and drinking (Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007; Young, Connor, Ricciardelli, & Saunders, 2006; Zamboanga et al., 2006).

The conflicting findings regarding negative expectancies might be explained by considering bidirectional relationships between alcohol use and expectancies. That is, alcohol expectancies may influence drinking behavior, but also, direct experiences with alcohol and its consequences may subsequently influence and shape expectancies (Patrick & Maggs, 2008). For positive expectancies and alcohol use this relationship may be relatively straightforward. Alcohol consumption can lead to positive experiences that increase future positive expectancies which in turn promote subsequent drinking. Regarding negative expectancies, the relationship may be more complex. On the one hand, we might expect that individuals with stronger negative alcohol expectancies may be less motivated to drink, and subsequently drink less. However, if we consider the influence of drinking experiences on expectancies, we would predict that heavier drinkers who drink more per drinking occasion would experience more negative consequences, and in turn, develop stronger negative alcohol expectancies. To this end it may be the quantity of alcohol consumption during drinking occasions (and not necessarily the frequency of drinking occasions overall) that would be expected to result in negative consequences potentially strengthening negative expectancies. Therefore, a crucial next step in this area is to consider potentially unique relationships between negative expectancies and the frequency vs. quantity of alcohol consumption.

To date, much of the research examining relationships between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use comes predominantly from cross-sectional studies, which are limited to analyses that measure how expectancies differ between individuals at a between-person level. These studies have typically shown that individuals who have stronger positive alcohol expectancies, in general, are more likely to drink heavily and experience alcohol related problems. Recent research also demonstrates that alcohol expectancies fluctuate within-person at the daily level (Lee, Atkins, Cronce, Walter, & Leigh, 2015), and that days in which individuals report stronger positive and negative expectancies are associated with gender-specific high-intensity drinking (women/men consuming 8+/10+ drinks in a day; Patrick et al., 2016a). However, whether daily fluctuations in expectancies are associated with drinking at lower levels of consumption or influence decisions to drink or not drink at all remain unknown. Improving our understanding of these daily-level processes could provide more proximal intervention targets to prevent or reduce drinking on a given day.

Additionally, little is known regarding moderators of the relationship between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at the daily level. Identifying moderators of this relationship has important implications for interventions that challenge alcohol expectancies on college campuses (e.g., Darkes & Goldman, 1993, 1998; Scott-Sheldon, Terry, Carey, Garey, Carey, 2012). In particular, examining person-level characteristics as moderators may help identify who might benefit most from expectancy-related interventions, and examining situational characteristics may help identify when expectancy interventions might be most important to deliver if expectancies can be challenged in real-time. There are several person-level characteristics that warrant attention as potential moderators among college students in particular. For example, past research has shown greater reductions in drinking following expectancy-related interventions for males compared to females (Corbin, McNair, & Carter, 2001; Dunn, Lau, & Cruz, 2000). As a result, it may be the case that males have stronger associations between expectancies and drinking and therefore experience greater reductions in drinking as a result of challenged expectancies. Further, it may be fruitful to explore other person-level characteristics that have been previously linked to greater risk of college student alcohol misuse including membership to a fraternity/sorority (Capone, Wood, Borsari, & Laird, 2007). Finally, the examination of age and individual’s baseline rates of drinking and related problems as moderators has important implications for evaluating expectancy challenges as either prevention strategies for younger students with little or no history of drinking or as interventions for older college students with an established history of hazardous drinking.

Current Study

Using Interactive Voice Response (IVR) daily reports from a daily diary study, our primary study aims were 1) to examine associations between both positive and negative expectancies and same-day drinking, and 2) investigate moderators of associations between alcohol expectancies and same-day drinking. Consistent with alcohol expectancy theory, we hypothesized that alcohol consumption would be more likely and greater on days when one has higher levels of positive alcohol expectancies than his/her average. With regard to negative expectancies and alcohol use, we considered competing hypotheses. First, it is possible that individuals who expect worse outcomes from alcohol relative to their typical expectancies may be less motivated to drink and either refrain from drinking or drink less than is typical. However, it is also possible that individuals who drink more have experienced more negative consequences and that expectancies of these consequences are stronger on days when drinking is likely to occur. We made several hypotheses regarding potential moderation effects. First, we predicted that both positive and negative alcohol expectancies would be more strongly associated with same-day drinking for males based on findings from alcohol expectancy intervention studies (Corbin et al., 2001; Dunn et al., 2000). Consistent with alcohol expectancy theory, we also predicted that overall patterns of heavy drinking would be influenced by heightened positive expectancies, and that lighter patterns of drinking would be more influenced by heightened negative expectancies. To this end, we predicted that positive alcohol expectancies would be more strongly associated with same-day drinking for heavier drinkers with more alcohol-related problems, and that negative expectancies would be more strongly associated with same-day drinking for lighter drinkers with fewer alcohol-related problems. We also included several additional variables as moderators in exploratory analyses with no specific hypotheses made regarding predicted effects. We specifically explored several person-level characteristics, including fraternity/sorority membership, age, and overall levels of positive and negative expectancies, as moderators to see who might benefit most from expectancy-related interventions. We also examined “college weekend” (i.e., Thurs-Sat) as a moderator to explore when expectancy interventions might be most important deliver.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 327 undergraduate students (mean age 19.7 [SD = 1.3], 53.8% female) from a large public university in the Pacific Northwest who agreed to participate in a longitudinal study examining daily-level alcohol use, alcohol expectancies and consequences. Participants were freshmen (17.3%), sophomores (36.7%), or juniors (46.0%), and most participants identified as White/Caucasian (73.7%), with the remainder Asian American (8.9%), multiracial (11.6%), or other (5.8%); 9.2% across races identified as Hispanic or Latino. Approximately 54.7% of the sample reported membership in a fraternity or sorority. The University IRB approved all procedures and a federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health. All participants completed online informed consent procedures before beginning the study.

Procedures

College students were randomly selected from the university’s registrar’s lists and invited by mail and email to complete a brief online screening survey to determine eligibility for the study. The survey website included an informational statement with all elements of informed consent and a brief survey to assess demographics, alcohol use, and mobile phone capabilities. Eligibility criteria for the longitudinal study included: being a freshman, sophomore, or junior at the university (at baseline); being 18-24 years old; drinking at least twice per week in the last month (to ensure variability in primary study variables); owning a cell phone with a monthly plan; and agreeing to use the cell phone for the study and receive text messages.

3,210 students completed the screening survey and were compensated $10 for its completion. Of these students, 539 met eligibility criteria and were invited to complete a baseline survey to assess baseline demographics, alcohol use, consequences, and other psychosocial measures. Upon completion, participants were immediately invited to schedule an appointment to begin participation in the daily diary portion of the study. They met with a research assistant who obtained consent for longitudinal participation and completed a training session to review study procedures, including how to use the IVR system. The day after the training session, participants began the first 2-week period of daily assessments. Of the 539 who met eligibility, 516 completed the baseline survey and were compensated $30 for its completion, and 352 participated in the in-person training session and were enrolled into the longitudinal daily study. Of these 352 participants, 327 participants completed all study measures necessary for inclusion in analyses. The 352 participants enrolled into the daily study did not differ from those who completed baseline but did not participate in the daily study with regard to age, sex, typical alcohol consumption, hazardous drinking, and alcohol-related negative consequences (all ps > .05).

Daily assessments occurred for eight total weeks via automated telephone interviews using IVR completed via the participant’s mobile phone, resulting in up to 56 possible interview days. These eight weeks were divided into four 2-week daily reporting periods over the course of one year (i.e., two-week intervals that were selected randomly in each of four academic quarters). During these intervals, participants were asked to complete three interviews each day: morning (9am-noon), afternoon (3pm-6pm) and evening (9pm-midnight). Each interview took less than 10 minutes to complete and participants were compensated $2 for each complete interview, plus a bonus of $16 if they completed at least 85% of all possible interviews for each two-week period. Participants provided partial or completed interviews for at least one daily interview on 91.5% of 56 possible interview days. The mean number of partial or complete interviews was 141 out of 168 possible assessments (84%) and the majority of participants (88%) were retained through one year.

Measures

Demographic information

collected at screening included age (coded as 0 for under 21, 1 for 21+; used as cutoff given age of legal alcohol consumption in U.S.), sex (coded as 0 for males, 1 for females), and Greek status (coded as 0 for non-members, 1 for members of fraternity/sorority).

Baseline assessments.

Alcohol use at baseline was assessed by the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) and was scored as the average drinks per week in the three months preceding the study. Alcohol-related problems were assessed using the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989), a 23-item measure for assessing negative consequences that result from drinking and scored such that greater summary scores indicate more negative consequences.

Daily assessments.

All daily assessments of alcohol consumption were administered during the morning interviews and asked participants about drinking from yesterday, specified as “from the time you got up to the time you went to sleep.” Students reported the number of drinks they consumed in total from the previous day using an open-ended response format. From these interviews, we calculated each participant’s daily alcohol consumption in standard drinks. For each day, we also included study period (coded from 0 for 1st quarter of daily reporting, to 3 for 4th quarter of daily reporting) and college weekend (coded 0 from Sunday to Wednesday, 1 from Thursday to Saturday; weekend included Thursday given increased likelihood of college student drinking relative to other weekdays, Wood, Sher, & Rutledge, 2007). Daily assessments of alcohol expectancies were administered during afternoon reports using a validated measure intended for daily use (Lee et al., 2015). This measure has been shown to have a two-factor structure (e.g., positive/negative) with each subscale demonstrating excellent reliabilities at both between- and within-person levels (Lee et al., 2015). The measure asks students to report how likely they would be to experience a variety of effects if they were to consume alcohol later in the same day (i.e., before going to sleep for the night). Participants rated their responses on a 1-9 scale (1 = very unlikely, 9 = very likely) indicating the likelihood of each outcome. Positive outcomes included feeling more relaxed, being more sociable, being in a better mood, getting a buzz, having more desire for sex, feeling more energetic, and being able to express feelings more easily. Negative outcomes included having a hangover, becoming aggressive, feeling nauseated or vomiting, hurting or injuring oneself, being unable to remember what happened, being unable to study, being rude or obnoxious, and doing something embarrassing. Participants were not told which outcomes were coded as positive or negative, and outcome assessments were intermixed in interviews. Summary scores were computed by calculating separate mean ratings for positive expectancies and negative expectancies.

Data analytic strategy

Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) generalized linear mixed effects models (GLMMs) were performed to examine associations between drinking and positive and negative alcohol expectancies at the between- and within-person levels. Specifically, models examined associations between positive and negative alcohol expectancies reported on a given day with subsequent same-day drinking (retrospectively reported the following morning). A Bayesian form of the GLMM was selected because of the complex nature of the data that makes estimation of parameters more difficult (Hamra, MacLehose, & Richardson, 2013). Given that participants reported no alcohol consumption on more than half of the days in the monitoring period, we used a hurdle form of the GLMM. This approach involves performing two simultaneous tests; a logistic model that estimates odds ratios (ORs) for the likelihood of drinking (any vs. none) on any given day; and a count model that estimates rate ratios (RRs) for the count of standard drinks consumed on days on which at least one drink was consumed. RRs can be interpreted as the proportional change in the count associated with a 1-unit increase in the covariate (Atkins, Baldwin, Zheng, Gallop, & Neighbors, 2013). For the count portion of the model, a quasi-Poisson model was performed due to evidence of over-dispersion.

Given our interest in within-person changes in expectancies, we entered two separate variables together in the model to disentangle between- and within-person effects (Curran and Bauer, 2011; Palta, 2003). To capture between-person effects, for each participant, j, we calculated the mean of his/her given expectancy score () during the measurement period. A separate time-varying variable was then created as the deviation from the mean expectancy score for person j on day i (). For ease of interpretation, both the between-person average and the within-person daily deviation variables were standardized with mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. All models were adjusted for college weekend, Greek status, sex, age, study period, and typical alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems assessed at baseline. We also conducted hurdle GLMMs that tested for moderation by examining interactions between a number of our covariates (Greek status, sex, age, typical baseline alcohol consumption, baseline alcohol-related problems, college weekend, and overall expectancies across the monitoring period) and daily deviations in expectancies from one’s average in predicting these same drinking outcomes.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive information for the sample separated by sex. Males reported significantly more drinks consumed per week at baseline than females but did not differ with regard to alcohol-related problems. The final sample for daily-level analyses consisted of 327 participants with 12,104 total daily observations. The mean number of drinks reported per day across all observations was 1.95 (SD=3.35) and the percentage of days when at least 1 drink was consumed was 36.3%. The mean positive alcohol expectancy score was 5.43 (SD=1.55) and the mean negative expectancy was 2.80 (SD=1.21). There appeared to be substantial within- relative to between-person variability in both positive and negative expectancies (Intra-class correlation [ICC] = .41 for positive expectancies and ICC = .44 for negative expectancies). Positive and negative expectancies were strongly correlated with the mean within-person correlation being .53 (SD = .30).

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics by Sex: Percentage or Mean (With Standard Deviation in Parentheses For Means)

| Variable | Males (n = 151) |

Females (n = 176) |

Overall (N = 327) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19.8 (1.3) | 19.6 (1.2) | 19.7 (1.3) |

| Greek Statusa | 57.0 | 52.8 | 54.7 |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 75.8 | 72.7 | 73.7 |

| Asian | 10.6 | 7.4 | 8.9 |

| Multiracial | 6.6 | 15.9 | 11.6 |

| Other | 7.9 | 3.9 | 5.8 |

| Hispanicb | 7.9 | 10.2 | 9.2 |

| Baseline drinks per weekc | 23.1 (13.7)1 | 15.2 (8.1)1 | 18.9 (11.7) |

| Baseline RAPI | 12.9 (9.1) | 11.8 (9.0) | 12.3 (9.0) |

Note.

Values reflect percentage that endorsed membership to a fraternity or sorority

Ethnicity and race were not considered mutually exclusive

Derived from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire conducted at baseline; RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index

t(325) = 6.43, p < .001.

Expectancies as predictors of drinking outcomes

Table 2 presents the results for hurdle models that examined positive and negative expectancies as predictors of both the likelihood of drinking on a given day and the quantity of alcohol consumption on drinking days. At the within-person level, there was a statistically significant positive association between positive expectancies on a given day and likelihood of drinking as well as number of standard drinks consumed on a drinking day. In other words, on drinking days when individuals expected that positive effects from alcohol were more likely, they consumed more alcohol. At the between-person level, higher person-mean positive expectancies (i.e., expectancies across the monitoring period) were significantly associated with greater likelihoods of drinking on a given day and a greater number of standard drinks consumed on drinking days.

Table 2.

Hurdle Models Predicting Likelihood and Quantity of Daily Alcohol Consumption

| Predictors | Logistic Portion of Model |

Count Portion of Model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | RR | 95% CI | p | |

| Intercept | 0.23 | 0.18, 0.28 | <0.001 | 4.27 | 3.97, 4.63 | <0.001 |

| Greek status | 0.69 | 0.55, 0.85 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.09, 1.27 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 1.19 | 0.96, 1.47 | 0.128 | 0.83 | 0.77, 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Baseline drinks per weeka, z-score | 1.15 | 1.02, 1.31 | 0.010 | 1.18 | 1.13, 1.22 | <0.001 |

| Baseline RAPI, z-score | 1.06 | 0.95, 1.18 | 0.304 | 1.01 | 0.98, 1.05 | 0.484 |

| Study period | 1.04 | 1.00, 1.08 | 0.068 | 0.98 | 0.96, 0.99 | 0.004 |

| Age, 21+ | 1.98 | 1.49, 2.55 | <0.001 | 0.90 | 0.82, 0.98 | 0.018 |

| Weekend | 2.10 | 1.87, 2.34 | <0.001 | 1.16 | 1.12, 1.20 | <0.001 |

| Person-mean positive expectancies | 1.21 | 1.12, 1.32 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.04, 1.11 | <0.001 |

| Daily deviation in positive expectancies | 1.58 | 1.47, 1.70 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.10, 1.15 | <0.001 |

| Person-mean negative expectancies | 0.76 | 0.70, 0.83 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 1.07, 1.13 | <0.001 |

| Daily deviation in negative expectancies | 1.18 | 1.12, 1.28 | <0.001 | 1.13 | 1.11, 1.15 | <0.001 |

Note. OR = Odds Ratio; RR = Rate Ratio; CI = Credible Interval. Greek status was dummy-coded (0 = no Greek affiliation, 1 = fraternity or sorority affiliation). Sex was dummy-coded (0 = men, 1 = women).

Derived from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire conducted at baseline. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index. Study period was dummy-coded (0 for 1st quarter of daily reporting to 3 for 4th quarter of daily reporting). Weekend was dummy-coded (0 = Sunday to Wednesday, 1 = Thursday to Saturday).

When examining negative expectancies, at the within-person level, stronger negative expectancies on a given day were associated with a greater likelihood of drinking and a greater number of standard drinks consumed on drinking days. In other words, on drinking days when individuals expected that negative effects from alcohol were more likely, they consumed more alcohol. At the between-person level, higher person-mean negative expectancies were associated with reduced odds of any drinking on a given day, but a greater number of standard drinks consumed on drinking days. That is, people who report stronger negative expectancies overall are less likely to drink on a given day, but more likely to consume a greater number of drinks when they do drink.

Moderators of the association between daily-level expectancies and drinking outcomes

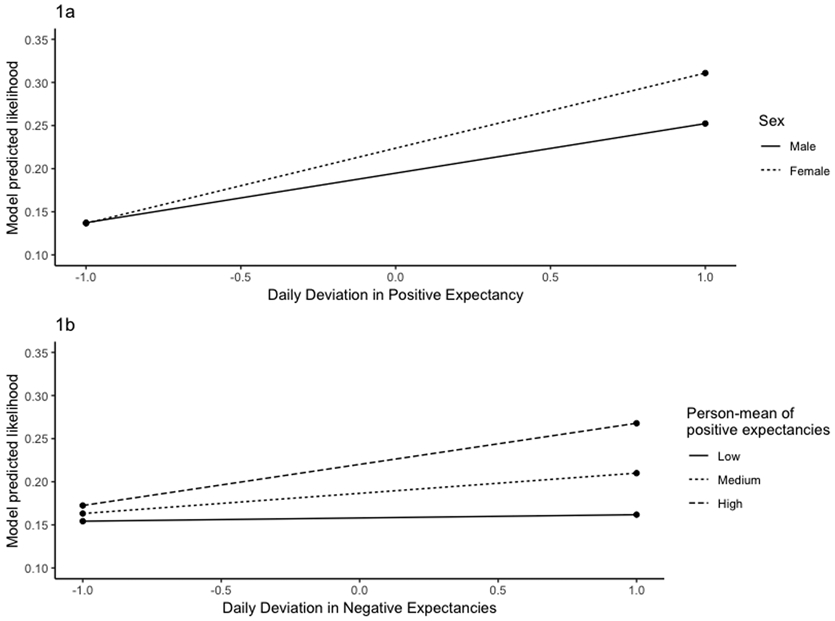

Table 3 presents parameters for interactions on their original log-odds or log-count scale between moderator variables and daily-level expectancies (positive and negative separately) in predicting drinking outcomes. When examining moderation of the association of daily expectancies with likelihood of any drinking, we found statistically significant moderation by sex and by one’s average positive expectancies across observations. To aid in interpretation of these significant interactions, Figure 1 plots descriptively show the model-predicted likelihood of any drinking according to the relevant daily expectancy variable and moderator. As shown in Figure 1a, while daily positive expectancies were positively associated with drinking in both males and females, the slope was steeper (i.e., the association was stronger among) females. For moderation by one’s average level of positive expectancies, there was a relatively flat slope between daily deviations in negative expectancies and any drinking among those with low average levels of positive expectancies. In contrast, for individuals with higher average levels of positive expectancies, the increasing slopes indicated that drinking was more likely on days with higher negative expectancies than their average (Figure 1b).

Table 3.

Hurdle Models Predicting Likelihood and Quantity of Daily Alcohol Consumption

| Interactions | Logistic Portion of Model |

Count Portion of Model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 95% CI | p | b | 95% CI | p | |

| Greek x Positive | 0.072 | −0.07, 0.19 | 0.286 | −0.024 | −0.07, 0.03 | 0.322 |

| Greek x Negative | 0.048 | −0.07, 0.18 | 0.504 | −0.035 | −0.07, 0.01 | 0.080 |

| Sex x Positive | 0.152 | 0.01, 0.28 | 0.030 | 0.020 | −0.03, 0.06 | 0.384 |

| Sex x Negative | −0.050 | −0.17, 0.09 | 0.442 | −0.012 | −0.05, 0.03 | 0.486 |

| Baseline Drinks Per Week x Positivea | 0.009 | −0.06, 0.07 | 0.790 | −0.027 | −0.05, −0.01 | 0.020 |

| Baseline Drinks Per Week x Negativea | −0.018 | −0.08, 0.04 | 0.568 | −0.007 | −0.02, 0.01 | 0.468 |

| Baseline RAPI x Positive | 0.003 | −0.06, 0.08 | 0.920 | 0.006 | −0.02, 0.03 | 0.638 |

| Baseline RAPI x Negative | 0.001 | −0.07, 0.06 | 0.956 | −0.011 | −0.03, 0.01 | 0.220 |

| Age x Positive | −0.149 | −0.35, 0.01 | 0.092 | 0.088 | 0.03, 0.15 | 0.002 |

| Age x Negative | 0.122 | −0.28, 0.05 | 0.156 | 0.016 | −0.03, 0.06 | 0.500 |

| Weekend x Positive | 0.009 | −0.11, 0.12 | 0.872 | −0.025 | −0.07, 0.01 | 0.218 |

| Weekend x Negative | 0.083 | −0.02, 0.20 | 0.146 | −0.032 | −0.06, 0.01 | 0.072 |

| Positive Expectancies x Positiveb | 0.007 | −0.06, 0.08 | 0.850 | 0.024 | 0.01, 0.05 | 0.030 |

| Positive Expectancies x Negativeb | 0.125 | 0.06, 0.19 | <0.001 | −0.004 | −0.03, 0.02 | 0.690 |

| Negative Expectancies x Positivec | −0.028 | −0.09, 0.04 | 0.374 | −0.018 | −0.04, 0.01 | 0.132 |

| Negative Expectancies x Negativec | 0.011 | −0.06, 0.08 | 0.726 | −0.027 | −0.05, −0.01 | 0.010 |

Note. CI = Credible Interval. Greek status was dummy-coded (0 = no Greek affiliation, 1 = fraternity or sorority affiliation). Sex was dummy-coded (0 = men, 1 = women).

Derived from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire conducted at baseline. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index. Study period was dummy-coded (0 for 1st quarter of daily reporting to 3 for 4th quarter of daily reporting). Weekend was dummy-coded (0 = Sunday to Wednesday, 1 = Thursday to Saturday).

Models reflect interactions between participant’s average positive expectancies across the study period and daily expectancies.

Models reflect interactions between participant’s average negative expectancies across the study period and daily expectancies.

Figure 1.

Model-predicted likelihood of any drinking according to daily deviations in expectancies and moderators of interest. Moderator variables include sex (1a), and person-mean positive expectancies across the monitoring period (1b).

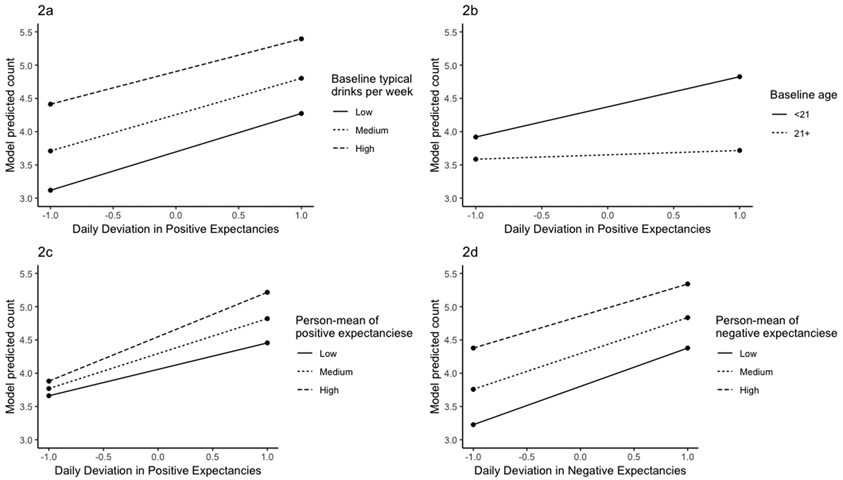

In the count portion of the model predicting quantity of drinks on drinking days, statistically significant moderation of daily positive or negative expectancies was observed by age, baseline levels of drinking, one’s average positive alcohol expectancies, and one’s average negative alcohol expectancies. Figure 2 plots descriptively show model-predicted count of drinks when drinking according to daily expectancies and the moderator. Figure 2a shows strong positive associations between daily positive expectancies and number of drinks at all levels of baseline drinking, with the slopes only slightly less steep among those who reported higher relative to lower levels of drinking at baseline. The figure also shows that compared to those with lower levels, individuals reporting high levels of baseline drinking consistently drank more on drinking days. When assessing age as a moderator, among those younger than 21 years, Figure 2b shows a stronger positive association between daily positive expectancies and drinks consumed relative to those older than 21. When examining moderation by average positive expectancies across observations, there was a steeper slope for the positive association between daily positive expectancies and drinks consumed with higher average levels of positive expectancies (Figure 2c). Finally, at all average levels of negative expectancies, we found that negative daily expectancies were strongly positive associated with number of drinks when drinking, but the slopes were slightly less steep for those with higher average levels of negative expectancies (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Model-predicted count of drinks on drinking days according to daily deviations in expectancies and moderators of interest. Moderator variables include baseline drinking (i.e. typical drinks per week, 2a), age at baseline (2b), person-mean positive expectancies across the monitoring period (2c), and person-mean negative expectancies across the monitoring period (2d).

Discussion

The current study sought to examine associations between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use at the daily-level and to examine several person- and occasion-level variables as potential moderators of these daily associations. Although previous research has demonstrated that individuals who have stronger positive outcome expectancies related to alcohol tend to drink more, findings regarding negative outcome expectancies are mixed, and few studies have examined how within-individual variation in expectancies predict subsequent drinking at the daily-level. The current study utilized a daily diary approach to address these gaps and examine associations between daily alcohol expectancies and subsequent drinking in the same day. Several important findings emerged.

There was substantial within-person and between-person variation in both positive and negative expectancies across the study period. Intra-class correlations suggest that about 40% to 45% of the observed expectancy variability can be attributed to between-person effects and 55% to 60% of the variability can be attributed to within-person effects (for ICC examination at an expectancy item-level analysis, see Lee et al., 2015). Stronger positive expectancies were associated with a higher likelihood of drinking and greater quantity of drinking on drinking days at both between-person and within-person levels. The between-person effect corroborates past research in which individuals that report stronger positive alcohol expectancies overall tend to be heavier drinkers (Fromme et al., 1993; Ham et al., 2005; Zamboanga, 2006; Zamboanga et al., 2006). This is the first study to demonstrate that within-person increases in positive expectancies are associated with a greater likelihood of any drinking and greater volume of alcohol consumption on the same day. Therefore, positive expectancies surrounding drinking are not static; they fluctuate over time and are meaningful in that increased positive expectancies are associated with heavier drinking (Patrick et al., 2016a). The findings suggest that intervention strategies that aim to reduce positive expectancies (e.g., Darkes & Goldman, 1993, 1998) target cognitive mechanisms that may help reduce hazardous drinking, and that challenging positive expectancies on occasions proximal to drinking events may be particularly beneficial.

In contrast to alcohol expectancy theory, stronger daily deviations of negative outcome expectancies were associated with a greater likelihood of drinking and greater amounts of alcohol consumed on drinking days. One potential explanation of this finding is that when participants were prompted to report their expectancies each day, they may have already planned to drink or not drink later in the day. In that sense, participants’ anticipation of drinking (or not drinking) may have affected their alcohol outcome expectancies. Given that both greater daily positive and negative outcome expectancies were associated with greater drinking outcomes, the anticipation of drinking may have enhanced individual’s perceived probabilities of experiencing alcohol-related outcomes regardless of their valence. In further support of this, positive and negative expectancies were strongly positively correlated within people, suggesting that determinants of within-person variation may cause alcohol-related expectancies to vary independent of whether those expectancies are positive or negative. A crucial next step of this line of research is to investigate real-world determinants (e.g., drinking intentions, contextual factors) of within-person variation in expectancies that may help further inform expectancy-related prevention and intervention strategies.

The findings introduce an interesting paradox, that is, college students are more likely to drink and drink more on days in which they expect both positive and negative effects are more likely to occur if they drink. To make sense of this paradox, one important factor to consider is that mean scores (reflecting perceived likelihood of an effect occurring) for positive expectancies were notably greater than for negative expectancies across the study. Although drinking was positively associated with both positive and negative expectancies at the daily level, it may be that students perceive positive effects to be more likely relative to negative effects. In this sense, positive expectancies may have more influence on drinking decisions even on days in which negative expectancies are stronger relative to one’s average negative expectancies.

Results regarding negative expectancies at the between-person level may shed light on prior conflicting findings in the literature (Fromme & D’Amico, 2000; Nicolai et al., 2010; Zamboanga et al., 2010). In the current study, person-mean negative expectancies had opposite associations with alcohol consumption depending on whether models predicted the likelihood of drinking or the amount of alcohol consumption on drinking days. Individuals with stronger negative alcohol expectancies on average were less likely to engage in drinking than those with weaker negative expectancies on average, however at the occasion level, individuals with stronger negative alcohol expectancies drank greater quantities on days when they did drink. Therefore, predictions made by alcohol expectancy theory may only apply to the frequency with which one drinks rather than the quantity one drinks. We may also consider a bidirectional relationship between alcohol effects and expectancies to explain the contradictory findings. That is, individuals who drink greater amounts carry stronger negative alcohol expectancies, perhaps as a result of the experiential phenomenon of experiencing more negative consequences associated with heavier drinking. In this sense, it may be that drinking greater amounts of alcohol, and not necessarily drinking more often, leads to negative consequences, which may lead to stronger negative expectancies. This may help explain conflicting findings in the literature, and future alcohol expectancy studies should give special consideration to whether assessments of drinking measure the frequency or quantity of alcohol consumption, or some combination of the two.

Several variables significantly moderated relations between daily fluctuations in expectancies and alcohol consumption. In particular, days with greater positive expectancies were more strongly associated with greater likelihoods of drinking among females, and days with greater positive expectancies were more strongly associated with greater amounts of alcohol consumption for younger students (i.e., under 21), students with lower baseline levels of drinking, and students with greater average levels of positive expectancies. This suggests that alcohol expectancy challenge interventions designed to modify positive expectancies might be particularly beneficial for these subgroups of college students (females, younger students, and those with greater overall positive expectancies), although it should be noted that previous studies have found greater reductions for drinking among males compared to females following alcohol challenge interventions (Corbin et al., 2001; Dunn et al., 2000). The results also suggest that modifying positive expectancies could be an effective means of alcohol misuse prevention for naïve or light drinkers given that positive expectancies were stronger predictors of alcohol consumption among students with lower baseline levels of drinking. Although further research is needed to understand the positive relationship between daily negative expectancies and drinking (in the context of competing positive expectancies), these negative expectancies were moderated by student’s overall average expectancies. Specifically, there were weaker positive associations between daily negative expectancies and quantity of alcohol consumed among individuals with stronger average negative expectancies and stronger positive associations between daily negative expectancies and likelihood of drinking among individuals with stronger average positive expectancies.

There are several study limitations to discuss. First, the sample was comprised entirely of college student drinkers, and whether the findings generalize to other populations of drinkers remains unknown. To this end, research has demonstrated that older drinkers may be more sensitive to alcohol’s negative effects compared to younger drinkers (e.g., Gilbertson, Ceballos, Prather, & Nixon, 2009), which may differentially impact the development of negative expectancies and their influence on drinking behavior. Second, although the study assessed a range of positive and negative outcomes taken from measures with good reliability and validity (i.e., CEOA; Fromme et al., 1993), these items do not represent the entirety of the drinking experience. Future studies may include additional outcomes that were not in the present study or may consider questions that assess positive and negative expectancies in a more general sense (i.e., “how positive or negative would you feel if you were to drink tonight?”). Third, to clarify our current findings, future studies should assess intentions to drink and anticipated amounts of alcohol consumption to determine whether these intentions are associated with expectancies and actual drinking.

Overall, this study provides support that positive expectancies are associated with greater levels of alcohol consumption both at a between- and within-person level. The association between negative expectancies and drinking behavior is more complex, and at the between-person level, may depend on whether studies assess the frequency or quantity of alcohol consumption. However, at the within-person level, reporting stronger negative expectancies compared to one’s average was associated with greater drinking outcomes, and overall, the findings suggest that enhanced expectations of both positive and negative outcomes are associated with heavier subsequent drinking. Finally, findings from moderation analyses carry several important clinical implications. In particular, interventions that are able to modify positive expectancies proximal to a drinking event may be particularly beneficial for females, younger students, and students with greater overall positive expectancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants R01AA016979 (PI: Lee), R01AA022087-03S1 (PI: Lee), R01AA023504 (PI: Patrick), and T32AA007455 (PI: Larimer). The funding sources had no other involvement other than financial support. The submitted manuscript is original, not previously published, and not under concurrent consideration elsewhere.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Atkins DC, Baldwin SA, Zheng C, Gallop RJ, & Neighbors C (2013). A tutorial on count regression and zero-altered count models for longitudinal substance use data. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27, 166–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Clerkin EM, Wood M, Monti PM, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Corriveau D, Fingeret A, & Kahler CW (2014). Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 75, 103–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, . . . Murphy S. (2008). A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics, 121, S290–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone C, Wood MD, Borsari B, & Laird RD (2007). Fraternity and sorority involvement, social influences, and alcohol use among college students: a prospective examination. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 316–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, & Marlatt GA (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53, 189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, McNair LD, & Carter JA (2001). Evaluation of a treatment-appropriate cognitive intervention for challenging alcohol outcome expectancies. Addictive Behaviors, 26, 475–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2011). The Disaggregation of Within-Person and Between-Person Effects in Longitudinal Models of Change. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 583–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, & Goldman MS (1993). Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: experimental evidence for a meditational process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 344–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, & Goldman MS (1998). Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: process and structure in the alcohol expectancy network. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 6, 64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, Lau HC, & Cruz IY (2000). Changes in activation of alcohol expectancies in memory in relation to changes in alcohol use after participation in an expectancy challenge program. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 8, 566–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, & Earleywine M (2001). Activation of alcohol expectancies in memory relation to limb of the blood alcohol curve. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 15, 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie AM, Ramirez JJ, Patrick ME, & Lee CM (2016). When do college students have less favorable views of drinking? Evaluations of alcohol experiences and positive and negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30, 555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, & D’Amico EJ (2000). Measuring adolescent alcohol outcome expectancies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 14, 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot EA, & Kaplan D (1993). Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 5, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson R, Ceballos NA, Prather R, & Nixon SJ (2009). Effects of acute alcohol consumption in older and younger adults: Perceived impairment versus psychomotor performance. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70, 242–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Brown SA, & Christiansen BA (1987). Expectancy theory: Thinking about drinking In Blane HT& Leonard KE (Eds.), Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism (pp. 181–226). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Del Boca FK, & Darkes J (1999). Alcohol expectancy theory: The application of cognitive neuroscience In Leonard KE& Blane HT (Eds.), Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism, Vol. 2 (pp. 203–246). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Stewart SH, Norton PJ, & Hope DA (2005). Psychometric assessment of the Comprehensive Effects of Alcohol questionnaire: Comparing a brief version to the original full scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 27, 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hamra G, MacLehose R, & Richardson D (2013). Markov Chain Monte Carlo: an introduction for epidemiologists. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42, 627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, & Weitzman ER (2009). Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement, s16, 12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Atkins DC, Cronce JM, Walter T, & Leigh BC (2015). A daily measure of positive and negative alcohol expectancies and evaluations: documenting a two-factor structure and within- and between-person variability. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76, 326–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Cronce JM, Baldwin SA, Fairlie AM, Atkins DC, Patrick ME, Zimmerman L, Larimer ME, & Leigh BC (2017). Psychometric analysis and validity of the daily alcohol-related consequences and evaluations measure for young adults. Psychological Assessment, 29, 253–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Maggs JL, Neighbors C, & Patrick ME (2011). Positive and negative alcohol-related consequences: associations with past drinking. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, & Larimer ME (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai J, Demmel R, & Moshagen M (2010). The comprehensive alcohol expectancy questionnaire: Confirmatory factor analysis, scale refinement, and further validation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92, 400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palta M (2003). Quantitative methods in population health: Extensions of ordinary regression. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL (2004). Positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students. Addictive Behaviors, 29, 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Cronce JM, Fairlie AM, Atkins DC, & Lee CM (2016). Day-to-day variations in high-intensity drinking, expectancies, and positive and negative alcohol-related consequences. Addictive Behaviors, 58, 110–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, & Maggs JL (2008). Short-term changes in plans to drink and importance of positive and negative alcohol consequences: Between- and within-person predictors. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 307–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, & Schulenberg JE (2011). How trajectories of reasons for alcohol use relate to trajectories of binge drinking: National panel data spanning late adolescence to early adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 47, 311–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM, Kloska DD, & Schulenberg JE (2016). High-intensity drinking among young adults in the United States: Prevalence, frequency, and developmental change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(9), 1905–1912. doi: 10.1111/acer.13164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA, & Patrick ME (2019). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018: Volume II, college students and adults ages 19–60. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, & Maggs JL (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, s14, 54–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Terry DL, Carey KB, Garey L, & Carey MP (2012). Efficacy of expectancy challenge interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analytic review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(3), 393–405. doi: 10.1037/a0027565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman KJ (2003). College students’ early cessation from episodic heavy drinking: prevalence and correlates. Journal of American College Health, 51, 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, & Hingson R (2013). The burden of alcohol use: excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 35, 201–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, & Labouvie EW (1989). Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 50, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PK, Sher KJ, & Rutledge PC (2007). College student alcohol consumption, day of the week, and class schedule. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 31, 1195–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RM, Connor JP, Ricciardelli LA, & Saunders JB (2006). The role of alcohol expectancy and drinking refusal self-efficacy beliefs in university student drinking. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 41, 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL (2006). From the eyes of the beholder: Alcohol expectancies and valuations as predictors of hazardous drinking behaviors among female college students. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 32, 599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Horton NJ, Leitkowski LK, & Wang SC (2006). Do good things come to those who drink? A longitudinal investigation of drinking expectancies and hazardous alcohol use in female college athletes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Ham LS, Borsari B, & Van Tyne K (2010). Alcohol expectancies, pregaming, drinking games, and hazardous alcohol use in a multiethnic sample of college students. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34, 124–133. [Google Scholar]