Abstract

A pregnant woman with KCNQ1 variant long QT syndrome (LQTS) underwent fetal magnetocardiography (fMCG) after atrioventricular (AV) block was noted during fetal echocardiogram - atypical for LQTS type 1. Concern for fetal LQTS on fMCG prompted monitoring of maternal labs, change of maternal beta blocker therapy, and frequent fetal echocardiograms. Collaboration between obstetricians, neonatologists and pediatric cardiologists ensured safe delivery. Beta blocker therapy was initiated after birth, and postnatal evaluation confirmed genotype and phenotype positive LQTS in the infant. Our experience suggests diagnosis and evaluation of fetal LQTS can alter antenatal management to reduce risk of poor fetal and postnatal outcomes.

Keywords: long QT syndrome, fetal bradycardia, fetal magnetocardiography, fetal echocardiography

Introduction:

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) affects up to 1 in 2500 individuals and can result in sudden cardiac death.1 Timely recognition of the disease is crucial. Findings on fetal echocardiography can suggest the diagnosis but are not confirmatory. Fetal magnetocardiography (fMCG) is a non-invasive tool to evaluate fetal cardiac electrical activity. High sensitivity Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (SQUID) sensors are utilized to safely record magnetic fields generated by the fetal heart and amplify the signals to produce a tracing similar to a conventional electrocardiogram. We present a case where fMCG served as a useful complement to fetal echocardiography to provide a family with full in utero assessment and to guide both prenatal and postnatal counseling and management.

Case History:

A 39-year-old gravida 1 para 0 Filipino woman with genotype positive (KCNQ1 G314D mutation) congenital LQTS type 1 was referred for fetal echocardiography at 22 weeks due to fetal bradycardia at 60 bpm during a routine antenatal visit with her obstetrician. She was diagnosed with LQTS at 11–12 years of age following multiple episodes of syncope and underwent pacemaker implantation shortly after her diagnosis. She was also managed with beta blocker therapy. After her positive pregnancy test, she was switched from nadolol 40 mg twice daily to long-acting propranolol 160 mg daily due to her fertility specialist’s reluctance to use nadolol during pregnancy.

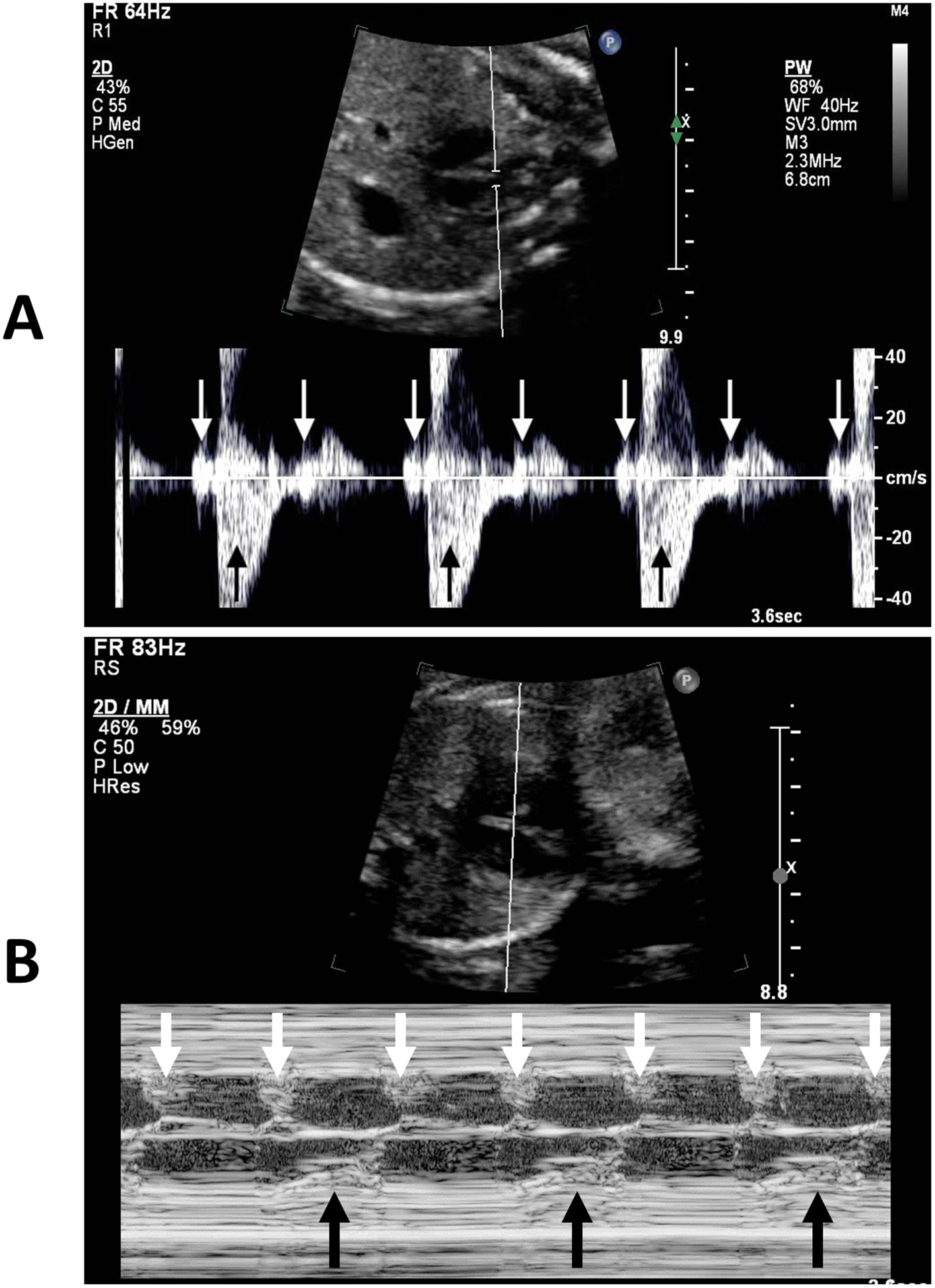

Fetal echocardiography showed a structurally normal heart with no cardiomegaly or signs of hydrops, mild mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation, and normal systolic function. Fetal rhythm showed 2:1 atrioventricular (AV) block with atrial rate of 120 bpm, ventricular rate of 60 bpm, and AV interval of 120 ms (Figure 1A–B). In the setting of a structurally normal heart, the differential diagnosis included maternal auto-immune diseases and fetal channelopathies.2 Maternal labs for anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies, vitamin D level, magnesium, and calcium were sent and unremarkable.

Figure 1: A) Doppler through the superior vena cava and aorta showing 2:1 atrioventricular block (white arrows: atrial contraction, black arrows: ventricular contraction). B) M-mode through the atrium and ventricle showing 2:1 atrioventricular block (white arrows: atrial contraction, black arrows: ventricular contraction).

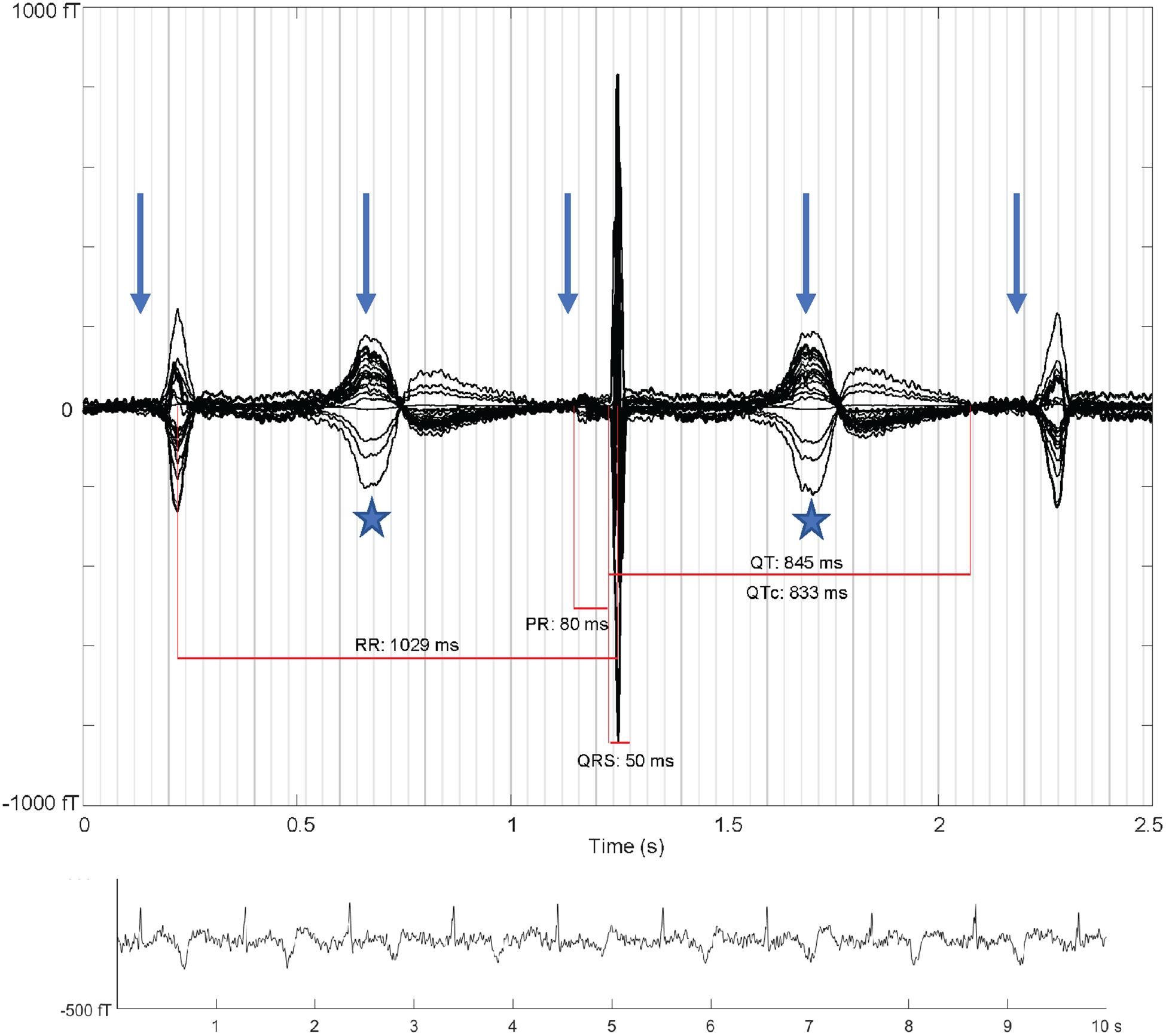

She was referred for fMCG (Tristan 624 Biomagnetometer, Tristan Technologies, Inc, San Diego, CA), which was performed in a magnetically shielded room at 22 5/7 weeks gestation.3 Testing initially showed sinus bradycardia with a rate of 120 bpm, minimal heart rate variability and brief sinus pauses. The QTc interval during normal AV conduction was 530 ms with uniform T-wave morphology. The fetus then developed 2:1 AV block with a ventricular rate of 59 bpm. The QTc in 2:1 AV block was markedly lengthened to 833 ms with variability in T-wave morphology (Figure 2). No obvious ventricular arrhythmias were noted. The mean normal QTc interval by fMCG at 15–24 weeks gestation is reported to be 398.4 ± 50.1 ms.4 Given the fMCG findings and autosomal-dominant transmission of LQTS, the mother was transitioned to non-sustained release propranolol of 60 mg every 8 hours and subsequently 80 mg every 8 hours for a more reliable presumed effect of the drug on fetal rhythm. The maternal QTc improved from >500 ms to 480 ms after the medication change.

Figure 2. Averaged fMCG waveform showing 2:1 atrioventricular block with three QRS complexes (arrows: P-waves, stars: T-waves). The averaging procedure time-aligns the middle QRS complex, and due to heart rate variation the other two QRS complexes are of reduced amplitude. The QTc is markedly prolonged with late-peaking T-wave morphology characteristic of fetal long QT syndrome. The rhythm tracing at the bottom of the figure shows variation in T-wave morphology during 2:1 atrioventricular block.

She was instructed to perform twice daily fetal Dopplers at home and seek medical care if the fetus was noted to have an irregular heart rhythm and/or heart rate < 70bpm or > 170 bpm. The lower rate was chosen to differentiate between worsening AV conduction and blocked atrial bigeminy, which has been shown to have a higher average fetal heart rate than 2:1 AV block.2 If the heart rate did not fall below what was already seen in the fetus, it was felt conduction disease had not worsened, and the likelihood of hydrops was low. The upper rate limit was chosen based on reported normal fetal heart rates to avoid missing torsades de pointes.3,4 The mother did not call about abnormal fetal Dopplers.

Weekly fetal echocardiograms continued to show sinus rhythm between 102–132 bpm with no AV block and AV intervals 96–144 ms, normal cardiac function and no signs of fetal hydrops. Repeat fMCGs showed fetal sinus rhythm with QTc intervals < 600 ms. Electrolytes were optimized prior to induction of labor, and QTc prolonging drugs were avoided when possible.

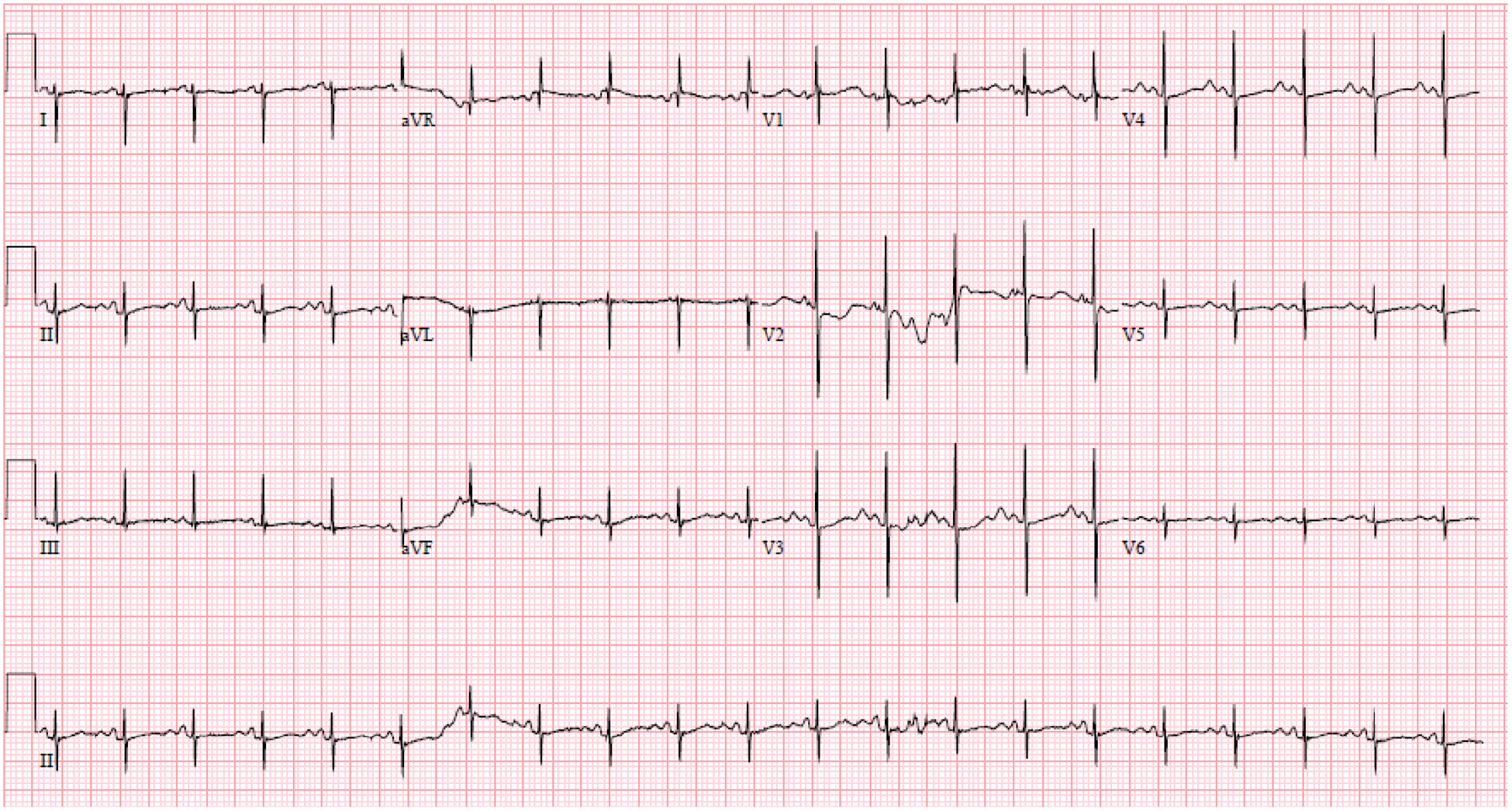

The infant male was born at 38 and 6/7 weeks gestation via cesarean section with no complications during delivery. The neonatal intensive care team was present at delivery with magnesium available in case of postnatal torsade de pointes. Per the prenatal plan determined by a team of obstetricians, neonatologists, and pediatric cardiologists, he was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit where telemetry revealed sinus bradycardia with minimal heart rate variability. Postnatal ECG showed normal sinus rhythm at 125 bpm, prolonged QTc at 589 ms, and markedly abnormal late peaking T-waves suggestive of congenital LQTS (Figure 3). He was started on beta blocker therapy with propranolol (starting dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day, discharge dose of 2.5 mg/kg/day) and discharged at 7 days of age. Genetic testing for the familial gene revealed the KCNQ1 variant, c.941G>A (p.Gly314Asp).

Figure 3. Infant’s first postnatal electrocardiogram on day of life 0 with normal sinus rhythm at 125 bpm, PR 92 ms, QRS 52 ms, QT 408 ms, prolonged QTc at 589 ms, and markedly abnormal late peaking T-waves suggestive of congenital long QT syndrome.

Discussion:

Comprehensive fetal evaluation with echocardiography and fMCG may be warranted for high-risk diagnoses such as LQTS, particularly when care modifications can be made in utero to reduce the chance of fetal demise. Although echocardiography recognized fetal bradycardia and AV block, fMCG definitively demonstrated QTc prolongation in this case prompting quick modification of maternal care and preparation for a potentially high-risk delivery. Prior literature suggests that ≥10% of fetal and neonatal sudden deaths may be the result of genetic or acquired ion channelopathies - LQTS being the most common cause of arrhythmia-related death in infants and children.5,6 In our case, fMCG findings prompted an attempt at modification of maternal medication management. Switching from long-acting to short-acting propranolol and increasing the beta blocker dose seemed to decrease the maternal QTc and alter the arrhythmia course in the fetus, since AV block and T-wave morphology variability were not seen after the change and repeat fMCGs showed QTc < 600 ms during sinus rhythm. The serum concentration of long-acting propranolol is 30–50% less than the short-acting version, which may explain the reason for the increased effect of the drug on the maternal QTc.7

LQTS type 1 fetuses typically do not manifest the severe QTc lengthening (>600 ms) associated with high-risk rhythm abnormalities such as second degree AV block, T-wave alternans, or torsade de pointes.5 Prior literature shows these findings are typically seen in patients with SCN5A and KCNH2 mutations.1,5,8 Fetuses with a KCNQ1 mutation like our patient most commonly present with sinus bradycardia as the only rhythm abnormality, so his findings of 2:1 AV block and T-wave morphology variability were unexpected.5,8 Our patient’s variant in KCNQ1 (G314D) is rare and not found in major population databases but has been reported in individual patients in the literature.3,8,9 The approximate variant location was depicted on channel topology of the IKs α-subunit encoded by KCNQ1 by Choi, et al.9 The combination of the baby’s fetal presentation, degree of QTc prolongation on fMCG and late-peaking T-waves on postnatal ECG suggests that the child may have a compound mutation (e.g., KCNQ1 plus SCN5A). Our patient was tested for the familial KCNQ1 variant, but additional genetic testing after discussion with family may need to be considered to further investigate.

Fetal echocardiographic parameters such as left ventricular isovolumetric relaxation time (L-IVRT) may also be useful in the prenatal diagnosis of LQTS as a mechanical representation of repolarization. A prolonged L-IVRT has been associated with LQTS in some patients.10 As an observational exercise, we retrospectively measured the normalized L-IVRT (L-IVRT/atrial cycle length ×100) via Doppler at the mitral inflow and aortic outflow during both 2:1 AV block and sinus bradycardia. As reported in Clur, et al., the optimal normalized L-IVRT cutoff value for diagnosis of LQTS at 21–30 weeks gestational age is 14.2% (C.I. 11.9–14.3%).10 At our patient’s 22 week gestation scan in 2:1 AV block, the normalized L-IVRT was 20% (100 ms/500 ms ×100) - well above the reported cutoff value.10 At the 23 week gestation scan in sinus bradycardia, the normalized L-IVRT was 11% (50 ms/450 ms ×100) - within the reported normal range.10 This suggests fetal L-IVRT may correlate to fetal QT and could be monitored as maternal treatment is adjusted.

Early identification of LQTS is not only important for outcomes in fetal life, but prenatal diagnosis can alter management to reduce the risk of torsade de pointes at delivery and help anticipate appropriate postnatal concerns. Although genetic predisposition to high-risk fetal arrhythmias may point clinicians towards closer monitoring during pregnancy, our case shows even mutations like KCNQ1 that typically present with subtle sinus bradycardia may present with concerning fetal rhythm abnormalities leading to postnatal complications. Refinement of prenatal diagnostic techniques via a multidisciplinary approach is crucial in identifying at-risk fetuses, modifying maternal therapy, and preparing for postnatal care.

Disclosures:

National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant Number TL1TR001423 (Desai). National Institutes of Health R01HL063174 (Wakai).

References

- 1.Blais BA, Satou G, Sklansky MS, Madnawat H, Moore JP. The diagnosis and management of long QT syndrome based on fetal echocardiography. HeartRhythm Case Rep 2017; 3:407–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiggins DL, Strasburger JF, Gotteiner NL, Cuneo B, Wakai RT. Magnetophysiologic and echocardiographic comparison of blocked atrial bigeminy and 2:1 atrioventricular block in the fetus. Heart Rhythm 2013; 10:1192–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Yu S, Horigome H, Hosono T, Kandori A, Wakai RT. In utero diagnosis of long QT syndrome by magnetocardiography. Circulation 2013; 128(20):2183–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strand SA, Strasburger JF, Wakai RT. Fetal magnetocardiogram waveform characteristics. Physiol Meas 2019; 40(3):035002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuneo BF, Strasburger JF, Wakai RT. The natural history of fetal long QT syndrome. J Electrocardiol 2016; 49(6):807–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crotti L, Tester DJ, White WM, Bartos DC, Insolia R, Besana A, Kunic JD, et al. Long QT syndrome-associated mutations in intrauterine fetal death. JAMA 2013; 309:1473–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nace GS, Wood AJJ. Pharmacokinetics of long acting propranolol implications for therapeutic use. Clin-Pharmacokinet 1987;13:51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuneo BF, Etheridge SP, Horigome H, Sallee D, Moon-Grady A, Weng H, Ackerman M, et al. Arrythmia phenotype during fetal life suggests LQTS genotype: risk stratification of perinatal long QT syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2013;6(5):946–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi G, Kopplin LJ, Tester DJ, Will ML, Haglund CM, Ackerman MJ. Spectrum and frequency of cardiac channel defects in swimming-triggered arrhythmia syndromes. Circulation 2004;110(15):2119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clur SB, Vink AS, Etheridge SP, Robles de Medina PG, Rydberg A, Ackerman MJ, Wilde AA. Left ventricular isovolumetric relaxation time is prolonged in fetal long-QT syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11(4):e005797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]