Abstract

ATP is a cotransmitter released with other neurotransmitters from sympathetic nerves, where it stimulates purinergic receptors. Purinergic adenosine P1 receptors (coupled to Gi/o proteins) produce sympatho-inhibition in several autonomic effectors by prejunctional inhibition of neurotransmitter release. Similarly, signalling through P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors coupled to Gi/o proteins is initiated by the ATP breakdown product ADP. Hence, this study has pharmacologically investigated a possible role of ADP-induced inhibition of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive in pithed rats, using a stable ADP analogue (ADPβS) and selective antagonists for the purinergic P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors. Accordingly, male Wistar rats were pithed and: (i) pretreated i.v. with gallamine (25 mg/kg) and desipramine (50 μg/kg) for preganglionic spinal (C7-T1) stimulation of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive (n = 78); or (ii) prepared for receiving i.v. injections of exogenous noradrenaline (n = 12). The i.v. continuous infusions of ADPβS (10 and 30 μg/kg/min) dose-dependently inhibited the tachycardic responses to electrical sympathetic stimulation, but not those to exogenous noradrenaline. The cardiac sympatho-inhibition produced by 30 μg/kg/min ADPβS was (after i.v. administration of compounds) (i) unchanged by 1-ml/kg bidistilled water or 300-μg/kg MRS 2500 (P2Y1 receptor antagonist), (ii) abolished by 300-μg/kg PSB 0739 (P2Y12 receptor antagonist) and (iii) partially blocked by 3000-μg/kg MRS 2211 (P2Y13 receptor antagonist). Our results suggest that ADPβS induces a cardiac sympatho-inhibition that mainly involves the P2Y12 receptor subtype and, probably to a lesser extent, the P2Y13 receptor subtype. These receptors may represent therapeutic targets for treating cardiovascular pathologies, including stroke and myocardial infarctions.

Keywords: Cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive, Pithed rat, Purinergic receptor, Sympatho-inhibition

Introduction

Purinergic receptors are activated by nucleotides and nucleosides and, according to structural, transductional and operational criteria, are classified into three families [1–5]: (i) P1 (G protein-coupled receptors activated by adenosine), (ii) P2X (ligand-gated ionotropic receptors activated by ATP) and (iii) P2Y (G protein-coupled receptors mainly activated by ATP or ADP). Regarding their G protein-coupling, P2Y receptors have been broadly grouped into two subfamilies [4, 5], namely, Gq-coupled P2Y(1,2,4,6 and 11) receptors; and Gi/o-coupled P2Y(12,13 and 14) receptors. It is noteworthy that the P2Y11 receptor also couples to Gs proteins. This receptor exists in several species, including humans and dogs, but it seems to be absent in rodents [6, 7]; indeed the P2Y11 receptor gene does not appear to be present in the rodent genome [7].

Interestingly, ATP has been shown to be released as a cotransmitter together with catecholamines from cardiac sympathetic nerves [8], but it may also be released from other sources in the heart such as endothelium, platelets, red blood cells and ischaemic myocardium [9–13]. Although less than 10% of ATP in the synaptic cleft seems to originate from the synapse itself [14], nucleotide receptors such as purinergic P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors could significantly contribute to an inhibitory effect on the synapses. Remarkably, adenosine may also exert this inhibitory effect but, as reviewed by Yegutkin [15], the time needed to break down ATP to adenosine (i) is longer than the breakdown to ADP and (ii) requires the expression of several enzymes. Hence, inhibitory signalling with ADP would give a faster inhibition of noradrenaline release than adenosine.

Outside of platelet research, where the P2Y12 receptor antagonist clopidogrel was the first marketed anticoagulation drug [16], very few studies have investigated the functional role of Gi/o-coupled P2Y receptors. For example, some in vitro studies have shown that activation of purinergic P2Y12 and/or P2Y13 receptors inhibit (i) neurotransmitter release, using the agonist adenosine 5′-O-2-thiodiphosphate (ADPβS) [2]; (ii) depolarization-induced calcium increases in isolated sympathetic neurons [17]; and (iii) noradrenaline release from the sympathetic neurons innervating the mouse vas deferens [18, 19]. Nevertheless, as far as we know, no study has explored the neuromodulatory role of these receptors on heart rate in anaesthetized or pithed animals.

Indeed, some pharmacological studies in pithed rats have shown that the cardioaccelerator responses to preganglionic sympathetic nerve stimulation can be inhibited by activation of prejunctional receptors coupled to Gi/o proteins, including histamine H3 [20], dopamine D2 [21], adrenergic α2A/2C [22], serotonin 5-HT1B/1D [23] and purinergic P1 (mainly A1) [24] receptors. On this basis, the present study has investigated in pithed rats the inhibition of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive produced by the P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptor agonist ADPβS, by using the purinergic receptor antagonists MRS 2500 (P2Y1), PSB 0739 (P2Y12) and MRS 2211 (P2Y13) [3, 5, 8].

Materials and methods

Ethical approval of the study protocol

The experimental protocols of the present investigation were approved by our Institutional Ethics Committee on the use of animals on scientific experiments (CICUAL-Cinvestav; protocol number 0139-15), following the regulations established by the Mexican Official Norm (NOM-062-ZOO-1999) in accordance with the guide for the Care and Use of the Laboratory Animals in the USA [25], the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments in animals [26] and the Legislation for the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes (Directive 2010/63/EU(2010)).

General methods

Experiments were carried out in a total of 90 male normotensive Wistar rats (280–300 g, 8 weeks of age). The animals were housed in a special room at a constant temperature (22 ± 2 °C) and humidity (50%) at a 12/12-h light/dark cycle (light beginning at 07:00 h), with food and water freely available in their home cages. After anaesthesia with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and cannulation of the trachea, the rats were pithed by inserting a stainless steel rod through the orbit and foramen magnum, and down the vertebral foramen, as reported earlier [27]. Then, the animals were artificially ventilated with room air using a model 7025 Ugo Basile pump (56 strokes/min, stroke volume: 20 ml/kg; Ugo Basile Srl, Comerio, VA, Italy), as previously established [28].

After bilateral cervical vagotomy, catheters were placed in (i) the left and right femoral veins for the continuous infusions of ADPβS (or vehicle) and i.v. bolus injections of the antagonists, respectively, and (ii) the left carotid artery, connected to a Grass pressure transducer (P23XL, Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA) for the recording of the blood pressure signal. Heart rate was measured with a tachograph (7P4F, Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA) triggered from the blood pressure signal. Heart rate and blood pressure were recorded simultaneously by a model 7D Grass polygraph (Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA). The body temperature of each pithed rat (monitored with a rectal thermometer) was maintained at 37 °C by a lamp. At this point, the 90 rats were divided into two main sets; then, the responses to i.v. continuous infusions of either bidistilled water (vehicle) or ADPβS were investigated on the tachycardic responses induced by (i) preganglionic spinal (C7-T1) electrical stimulation of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive (set 1; n = 78) or (ii) i.v. bolus injections of exogenous noradrenaline (set 2; n = 12). The tachycardic stimulus-response curves (S-R curves) and dose-response curves (D-R curves) elicited by electrical sympathetic stimulation and exogenous noradrenaline, respectively, were completed in about 30 min, with no changes in the baseline values of resting heart rate or blood pressure. The sympathetic tachycardic stimuli (0.1–3 Hz) and the i.v. bolus injections of exogenous noradrenaline (0.1–3 μg/kg) were given using a sequential schedule at intervals of 3–5 min.

Experimental protocols

After the animals (n = 90) had been in stable haemodynamic conditions for at least 30 min, set 1 (n = 78) and set 2 (n = 12) were divided into different pretreatment groups and, subsequently, into the different subgroups (n = 6 each, with no exception; see below). Then, the following experimental protocols were applied.

Protocol I: selective electrical stimulation of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive

In the first set of rats (n = 78), the stainless steel rod was replaced by an enamelled electrode except for 1 cm length, 7 cm from the tip, so that the uncovered segment was located at C7-T1 of the spinal cord to allow selective preganglionic stimulation of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive, as previously reported [27]. Before electrical stimulation, the animals were pretreated with gallamine (25 mg/kg, i.v.) in order to avoid the electrically induced muscular twitching. Since the cardiac sympatho-inhibitory responses to several agonists in pithed rats are particularly more pronounced at lower frequencies of stimulation [29], all animals were systematically pretreated with desipramine (a noradrenaline-reuptake inhibitor, 50 μg/kg; i.v.) 10 min before each S-R curve [29]. Thirty min later, when the haemodynamic conditions were stable, baseline values of heart rate and diastolic blood pressure (a more accurate indicator of peripheral vascular resistance) were determined. Then, the preganglionic cardiac sympathetic drive was stimulated by applying trains of 10 s (monophasic rectangular pulses of 2 ms and 50 V), at increasing frequencies (0.1, 0.3, 1 and 3 Hz). When heart rate had returned to baseline levels, the next frequency was applied; this procedure was performed until the S-R curve was completed (approximately 30 min). Subsequently, the 78 animals were divided into three groups (n = 18, 30 and 30, respectively).

The first group (n = 18) was subdivided into three subgroups (n = 6 each) that received i.v. continuous infusions of, respectively, (i) vehicle (bidistilled water; 0.02 ml/min, given twice), (ii) ADPβS (3 and 10 μg/kg/min) and (iii) ADPβS (30 μg/kg/min). After 10 min, a S-R curve was performed again during the infusion of each dose of bidistilled water or ADPβS.

The second group (n = 30) was subdivided into five subgroups (n = 6 each) that received an i.v. bolus injection of, respectively, (i) vehicle (bidistilled water; 1 ml/kg), (ii) MRS 2500 (300 μg/kg), (iii) PSB 0739 (300 μg/kg), (iv) MRS 2211 (1000 μg/kg) and (v) MRS 2211 (3000 μg/kg). Ten min later, all subgroups received an i.v. continuous infusion of vehicle (0.02 ml/min). After 10 min, a S-R curve was elicited again as described above during the vehicle infusion, to analyse the effects of the above compounds per se on the sympathetically induced tachycardic responses.

The third group (n = 30) was subdivided into five subgroups (n = 6 each) that received an i.v. bolus injection of, respectively, (i) vehicle (bidistilled water; 1 ml/kg), (ii) MRS 2500 (300 μg/kg), (iii) PSB 0739 (300 μg/kg), (iv) MRS 2211 (1000 μg/kg) and (v) MRS 2211 (3000 μg/kg). Ten min later, all subgroups received an i.v. continuous infusion of ADPβS (30 μg/kg/min). After 10 min, a S-R curve was elicited again as described above during the ADPβS infusion, to analyse the effects of the above compounds on the ADPβS-induced cardiac sympatho-inhibition.

Protocol II: intravenous bolus injections of exogenous noradrenaline

The second set of rats (n = 12) was prepared as described above, but the pithing rod was left throughout the experiment, and the administration of both gallamine and desipramine was omitted, as previously described [27]. After a stable haemodynamic condition for 30 min, baseline values of diastolic blood pressure and heart rate were determined. Then, the animals received i.v. bolus injections of exogenous noradrenaline (0.1, 0.3, 1 and 3 μg/kg) to produce dose-dependent tachycardic responses. When the heart rate returned to baseline levels, the next dose was applied. This procedure was performed until the D-R curve was completed (approximately 30 min). Subsequently, this set of animals was divided into two groups (n = 6 each) that received i.v. continuous infusions of, respectively, (i) vehicle (bidistilled water; 0.02 ml/min) or (ii) ADPβS (30 μg/kg/min). Ten min later, a D-R curve to noradrenaline was elicited again during the infusion of vehicle or ADPβS.

Other procedures applying to protocols I and II

It is to be noted that the doses of (i) vehicle or ADPβS were continuously infused (i.v.) at a rate of 0.02 ml/min by a KD Scientific KDS100 model infusion pump (KD Scientific Inc., Holliston, MA, USA) and (ii) vehicles or antagonists were given as i.v. bolus injections in volumes of 1 ml/kg. The intervals between the different stimulation frequencies or noradrenaline doses depended on the duration of the tachycardic responses (5–10 min), as we waited until heart rate had returned to baseline values.

Compounds

Apart from the anaesthetic (sodium pentobarbital) used during the development of this experimental protocol, the compounds employed in the present study (obtained from the sources indicated) were gallamine triethiodide, desipramine hydrochloride, DL-noradrenaline hydrochloride, and adenosine-5′-[β-thio]diphosphate trilithium salt (ADPβS) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA); (1R*,2S*)-4-[2-Iodo-6-(methylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-(phosphonooxy)bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-1-methanol dihydrogen phosphate ester tetraammonium salt (MRS 2500); 1-amino-9,10-dihydro-9,10-dioxo-4-[[4-(phenylamino)-3-sulfophenyl]amino]-2-anthracenesulfonic acid sodium salt (PSB 0739) and 2-[(2-chloro-5-nitrophenyl)azo]-5-hydroxy-6-methyl-3-[(phosphonooxy)methyl]-4-pyridinecarboxaldehyde disodium salt (MRS 2211) (TOCRIS, Avonmouth, Bristol, UK). Except for gallamine, desipramine and noradrenaline (dissolved in physiological saline, which does not affect per se heart rate or blood pressure [20, 21, 22, 23]), all compounds were dissolved in bidistilled water, and this vehicle had no effect on the baseline values of heart rate and diastolic blood pressure (Table 1). Fresh solutions were prepared for each experiment. The doses mentioned in the text refer to the free bases of substances, except in the case of gallamine, desipramine and noradrenaline where they refer to the corresponding salts.

Table 1.

Values of heart rate and diastolic blood pressure before and 10 min after administration of several compounds

| Treatment | Doses | Heart rate (beats/min) |

Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | ||

| Bidist. water | 0.02 ml/mina | 182 ± 12 | 183 ± 15 | 39 ± 6 | 40 ± 6 |

| ADPβS |

3 μg/kg/mina 10 μg/kg/mina 30 μg/kg/mina |

194 ± 15 208 ± 12 215 ± 12 |

193 ± 14 203 ± 13 204 ± 13 |

31 ± 4 34 ± 7 24 ± 4 |

25 ± 2 28 ± 4 20 ± 3 |

| Bidist. water | 1 ml/kgb | 276 ± 15 | 273 ± 18 | 35 ± 4 | 38 ± 6 |

| MRS 2500 | 300 μg/kgb | 206 ± 11 | 203 ± 9 | 28 ± 2 | 29 ± 2 |

| PSB 0739 | 300 μg/kgb | 276 ± 7 | 279 ± 10 | 25 ± 3 | 28 ± 4 |

| MRS 2211 |

1000 μg/kgb 3000 μg/kgb |

238 ± 27 219 ± 15 |

252 ± 25 221 ± 15 |

33 ± 9 27 ± 4 |

35 ± 3 29 ± 4 |

Values are presented as means ± SEM. Bidist. water stands for bidistilled water (vehicle)

aDoses were administered as i.v. continuous infusions

bDoses were administered as i.v. bolus injections

Data presentation and statistical evaluation

All data in the text and figures are presented as the mean ± SEM. Initially, the difference between the changes in blood pressure and heart rate produced by the administration of antagonists or vehicle was evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. The peak changes in heart rate produced by either electrical sympathetic stimulation or exogenous noradrenaline in the bidistilled water- and ADPβS-infused animals were determined. The difference in the baseline values of heart rate and diastolic blood pressure within one subgroup of animals before and during the continuous infusions of bidistilled water or ADPβS (at the doses mentioned above) was evaluated with paired Student’s t test. Moreover, the difference between the changes in heart rate within one subgroup of animals was evaluated with the Student-Newman-Keuls test, once a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (randomized block design) had revealed that the samples represented different populations [30]. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05 (two-tailed). Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot 12.0 (Systat Software, Inc. SigmaPlot for Windows). The graphics were performed using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Systemic haemodynamic variables

The baseline values of diastolic blood pressure and heart rate in the 90 pithed rats were 36 ± 1 mmHg and 236 ± 4 beats/min, respectively. After the first i.v. bolus injection of desipramine (a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor), the values of diastolic blood pressure (but not heart rate) significantly increased (P < 0.05) to 44 ± 1 mmHg and returned to baseline values (37 ± 3 mmHg) after 5–10 min. The following treatments with desipramine produced no further significant changes (P > 0.05, data not shown). Additionally, in the different subgroups, the baseline values of heart rate and diastolic blood pressure were not significantly modified (P > 0.05) after administration of (i) i.v. continuous infusions of vehicle (bidistilled water) or ADPβS or (ii) i.v. bolus injections of vehicle (bidistilled water), MRS 2500, PSB 0739 or MRS 2211 (see Table 1).

Effect of i.v. continuous infusions of vehicle or ADPβS on the tachycardic responses produced by electrical sympathetic stimulation or exogenous noradrenaline

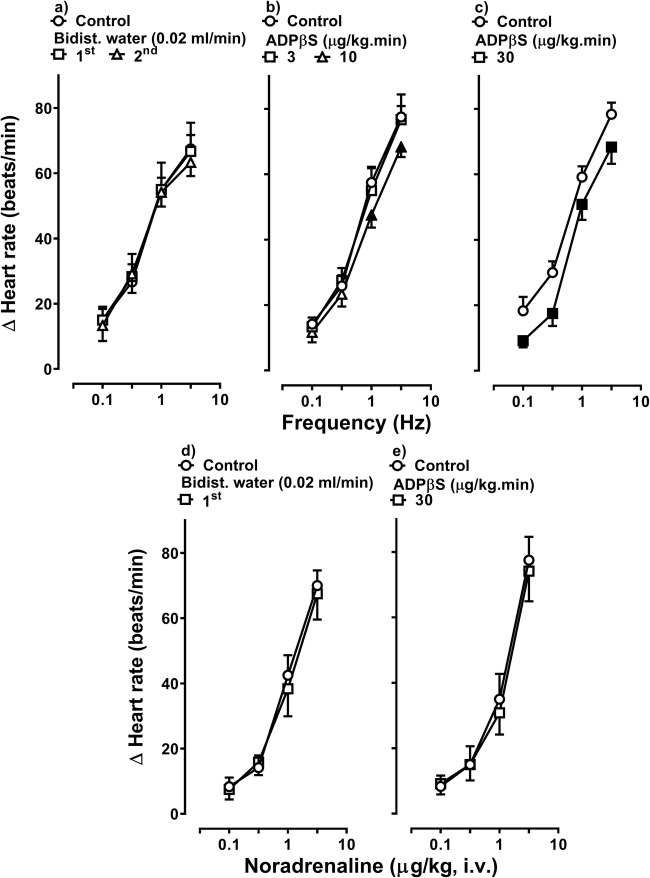

Figure 1 illustrates the tachycardic responses produced by (i) electrical sympathetic stimulation (S-R curves; upper panel) and (ii) i.v. bolus injections of exogenous noradrenaline (D-R curves; lower panel), before (control) and during administration of i.v. continuous infusions of bidistilled water (vehicle; 0.02 ml/min) or ADPβS (up to 30 μg/kg/min). Clearly, electrical sympathetic stimulation (0.1–3 Hz) and i.v. bolus injections of exogenous noradrenaline (0.1–3 μg/kg) resulted in frequency-dependent (upper panel) and dose-dependent (lower panel) increases in heart rate, respectively. In animals infused with vehicle (given twice for sympathetic stimulation or once for exogenous noradrenaline), these tachycardic responses remained unchanged (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1a and d), indicating that the responses were reproducible during our experimental protocols. In marked contrast, i.v. continuous infusions of ADPβS (10 and 30 μg/kg/min) produced a dose-dependent inhibition on the sympathetic tachycardic responses (Fig. 1b and c). In view that 30 μg/kg/min ADPβS produced a greater (P < 0.05) sympatho-inhibition at all stimulation frequencies (Figs. 1c and 2), this dose was selected to analyse its effect on the tachycardic responses to exogenous noradrenaline and the pharmacological profile of the P2Y receptors involved (see below).

Fig. 1.

Effect of vehicle or ADPβS on the tachycardic responses by electrical sympathetic stimulation or noradrenaline. Tachycardic responses produced by electrical sympathetic stimulation of the cardiac sympathetic drive (S-R curves; upper panels) or i.v. bolus injections of exogenous noradrenaline (D-R curves; lower panels) before (control) and during i.v. continuous infusions of (i) bidist. water (bidistilled water; a, d), (ii) 3 and 10 μg/kg/min ADPβS (b) or (iii) 30 μg/kg/min ADPβS (c, e) (n = 6 each subgroup). Empty symbols depict either control responses (◯) or non-significant (P > 0.05) responses (□,△) versus control. Solid symbols (■,▲) represent significant differences versus control (P < 0.05). Δ Heart rate stands for “increases in heart rate”

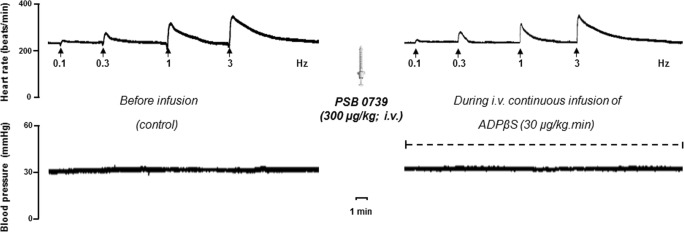

Fig. 2.

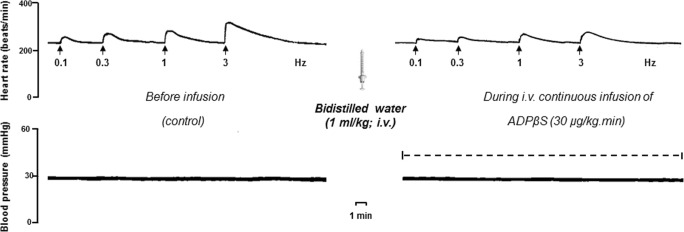

Original experimental recordings illustrating the increases in heart rate (beats/min) produced by electrical sympathetic stimulation (Hz) of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic outflow before (control) and during the i.v. continuous infusion of 30 μg/kg/min ADPβS. Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) remained unchanged throughout the experiments

Unlike the inhibition produced on the sympathetic tachycardic responses (Figs. 1c and 2), 30 μg/kg/min ADPβS failed to inhibit the noradrenaline-induced tachycardic responses (P > 0.05; Fig. 1e). This result suggests that ADPβS produces its sympatho-inhibitory effect by interacting with prejunctional P2Y receptors, for which it displays similar affinities (see Table 2). This sympatho-inhibition was also quantified as a percentage reduction at each stimulation frequency and at each dose of ADPβS (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Binding affinity constants of agonists and antagonists at Gi protein-coupled purinergic P2YGi-like receptors (which consist of the P2Y12, P2Y13 and P2Y14 subtypes)

| P2Y12 | P2Y13 | P2Y14 | P2Y1# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonists | ||||

| ADPβS | 7.5a | 7.5b | – | 5.6c,ϕ |

| UDP-G | – | – | 8d | – |

| Antagonists | ||||

| PSB 0739 | 7.6e | > 6f | > 6f | > 6f |

| MRS 2211 | > 5g | 6.3g | – | > 5g |

| MRS 2500 | > 4h | > 4i,Ψ | – | 9.1j |

Data collected from: a [40]; b [41]; c [42]; d [43]; e [44]; f [45]; g [46]; h [47]; i [48]; j [49]

All data are presented as pKi/pEC50 values at human receptors. It is important to note that the P2Y2, P2Y4 and P2Y6 receptor subtypes (which are also included in the family of P2Y receptors) are activated by UTP- or UDP-glucose, but not by ADPβS

#Note that several compounds also display some degree of affinity for the P2Y1 receptor subtype (a Gq-coupled receptor whose activation results in platelet aggregation) and that MRS 2179 is a selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist with similar structure and chemical properties as MRS 2500

ϕBehaves as a partial agonist

ΨBased on the compound MRS 2179

Table 3.

Percentage of inhibition produced by ADPβS (3, 10 and 30 μg/kg/min) on the tachycardic responses induced by electrical sympathetic stimulation at different frequencies of stimulation (0.1–3 Hz) in pithed rats

| Frequency (Hz) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 3 | |

| ADPβS (μg/kg/min) | Percentage of inhibition (%) | |||

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 18 ± 6* | 13 ± 4* |

| 30 | 40 ± 11*θ | 44 ± 8*θ | 16 ± 6* | 14 ± 4* |

Cardiac sympatho-inhibition induced by ADPβS in pithed rats

*P < 0.05 versus ADPβS 3 μg/kg/min

θP < 0.05 versus ADPβS 10 μg/kg/min

Effect of vehicle, MRS 2500, PSB 0739 or MRS 2211 per se on the sympathetic tachycardic responses

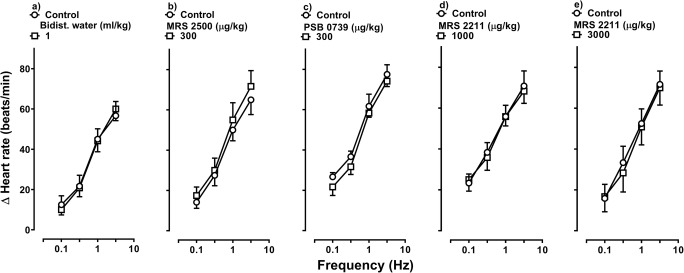

Figure 3 shows the sympathetic tachycardic responses before (control S-R curves) and after i.v. bolus injections of bidistilled water (1 ml/kg), MRS 2500 (300 μg/kg; P2Y1 receptor antagonist), PSB 0739 (300 μg/kg; P2Y12 receptor antagonist) or MRS 2211 (1000 and 3000 μg/kg; P2Y13 receptor antagonist). Clearly, the tachycardic responses induced by electrical sympathetic stimulation remained unchanged (P > 0.05) after i.v. administration of bidistilled water (Fig. 3a), MRS 2500 (Fig. 3b), PSB 0739 (Fig. 3c) or MRS 2211 (Fig. 3d, e). Likewise, the baseline values of heart rate and diastolic blood pressure remained unaltered (P > 0.05) after the administration of these compounds (see Table 1). These results suggest that, under our experimental conditions, the above compounds at the doses used were devoid of any effect per se on the sympathetic tachycardic responses.

Fig. 3.

Effect per se of vehicle or antagonists on the tachycardic responses produced by electrical sympathetic stimulation. Tachycardic responses produced by electrical sympathetic stimulation before and after i.v. bolus injections of a bidist. water (bidistilled water; 1 ml/kg), b MRS 2500 (300 μg/kg), c PSB 0739 (300 μg/kg), d MRS 2211 (1000 μg/kg) or e MRS 2211 (3000 μg/kg) (n = 6 each subgroup). Empty symbols represent either control responses (◯) or non-significant (P > 0.05) responses (□) versus control. Δ Heart rate stands for “increases in heart rate”

Effect of vehicle, MRS 2500, PSB 0739 or MRS 2211 on the ADPβS-induced inhibition of sympathetic tachycardic responses

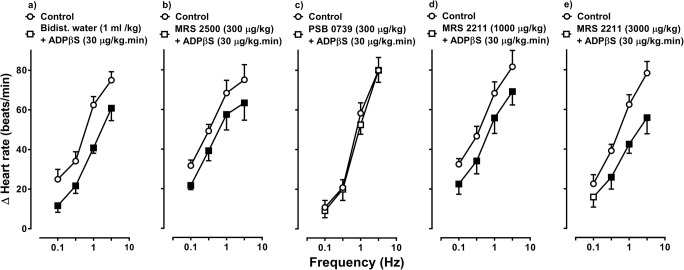

Figure 4 shows the effect of the i.v. bolus injections of bidistilled water (1 ml/kg), MRS 2500 (300 μg/kg), PSB 0739 (300 μg/kg) or MRS 2211 (1000 and 3000 μg/kg) on the inhibition of sympathetic tachycardic responses produced by 30 μg/kg/min ADPβS. In this respect, the ADPβS-induced cardiac sympatho-inhibition (i) remained unaltered at all stimulation frequencies after bidistilled water (Fig. 4a), 300 μg/kg MRS 2500 (P2Y1 receptor antagonist; Fig. 4b) or 1000 μg/kg MRS 2211 (Fig. 4d); (ii) was abolished after 300 μg/kg PSB 0739 (P2Y12 receptor antagonist Figs. 4c and 5); and (iii) was partially – and weakly – blocked (only at 0.1 Hz) after 3000 μg/kg MRS 2211 (P2Y13 receptor antagonist; Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

Effect of vehicle or antagonists on the ADPβS-induced cardiac sympatho-inhibition. Effect of i.v. bolus injections of a bidist. water (bidistilled water; 1 ml/kg), b MRS 2500 (300 μg/kg), c PSB 0739 (300 μg/kg), d MRS 2211 (1000 μg/kg) or e MRS 2211 (3000 μg/kg) (n = 6 each subgroup) on the inhibition of sympathetically induced tachycardic responses induced by an i.v. continuous infusion of 30 μg/kg/min ADPβS. Empty symbols depict either control responses (◯) or non-significant (P > 0.05) responses (□) versus control. Solid symbols (■) depict significantly different responses (P < 0.05) versus control. Δ Heart rate stands for “increases in heart rate”

Fig. 5.

Original experimental recordings illustrating the effect of an i.v. bolus injection of PSB 0739 (300 μg/kg) on the cardiac sympatho-inhibition produced by 30 μg/kg/min ADPβS. Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) remained unchanged throughout the experiments

Discussion

General

As previously pointed out [20–23, 27, 29, 31], the benefit of using the pithed rat model (which has no functional central nervous system) is that we can investigate the effects of drugs and their mechanisms of action in the periphery with no baroreflex compensatory mechanisms. Hence, we can categorically exclude any central effects of the compounds under study that can modify peripheral resistance or heart rate [20–23, 27, 29, 31]. Moreover, Mei and Liang [32] have previously shown in isolated mouse and rat hearts (using the Langendorff model) that the P2X receptor agonist 2-methylthio-ATP produced dose-dependent increases in the pressure developed in the left ventricle, contraction rate and relaxation rate, but the increase in contractility had no effect on the baseline heart rate. With these considerations in mind, our study in pithed rats suggests that (i) the purinergic P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptor agonist, ADPβS (at the doses used), specifically inhibits the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive in pithed rats and (ii) considering the effects of the antagonists, the cardiac sympatho-inhibition by ADPβS is mainly mediated by the P2Y12 receptor subtype and, to a much lesser extent (if any), by the P2Y13 receptor subtype (see below), but not by the P2Y1 receptor subtype. It must be emphasized that, under our experimental conditions, (i) the action of ADPβS was considered sympatho-inhibitory since this compound inhibited the tachycardic responses to electrical sympathetic stimulation (Figs. 1c and 2) without affecting those to exogenous noradrenaline (Fig. 1e) and (ii) the electrically induced neurotransmitter release was not directly measured, but it was determined indirectly by the evoked tachycardic responses induced by sympathetic stimulation, as previously reported [20–23, 27, 29, 31].

Systemic haemodynamic variables

The slight and transient vasopressor effect observed after desipramine administration (see Results section) can be attributed to inhibition of noradrenaline reuptake mechanisms in the perivascular sympathetic nerves [33]. This finding, which accounts for the potentiation of the sympathetically induced tachycardic responses after desipramine, mostly at low stimulation frequencies [29], allows us to show a sympatho-inhibition by ADPβS (Figs. 1c and 4a). When quantifying this sympatho-inhibitory response as a percentage reduction at each stimulation frequency and at each dose of ADPβS (Table 3), it is clear that the sympatho-inhibition produced by ADPβS, in addition to being dose-dependent, is particularly more pronounced at lower frequencies of stimulation, as previously shown for a wide variety of other prejunctional sympatho-inhibitory receptors [20–23, 34–36], including α2-adrenergic, dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT1 receptors. In this respect, it may be argued that the inhibition by ADPβS is simply due to tachyphylaxis of the tachycardic responses when eliciting a second (or third) S-R curve. This view, however, can be ruled out as the sympathetic tachycardic responses remained unchanged when repeating the S-R curves several times during i.v. continuous infusions of bidistilled water (Fig. 1a) or after i.v. bolus injections of bidistilled water (Fig. 3a). Accordingly, the tachycardic responses produced by electrical sympathetic stimulation (and also by exogenous noradrenaline; Fig. 1d) were clearly reproducible, indicating that no time-dependent changes occurred during our experimental protocols.

Additionally, the fact that i.v. continuous infusions of vehicle or ADPβS as well as i.v. bolus injections of vehicle, MRS 2500, PSB 0739 or MRS 2211 had no significant effects on heart rate or diastolic blood pressure (Table 1) allows us to infer that any effect of ADPβS or the antagonists is due to an interaction with their corresponding receptors (rather than the result of changes in these haemodynamic variables).

Effects of P2Y1, P2Y12 or P2Y13 receptor antagonists per se

As shown in Fig. 3, the fact that MRS 2500, PSB 0739 or MRS 2211 had no significant effects on the sympathetically induced tachycardic responses suggests that (i) the doses selected of these compounds are devoid of any effects per se on the tachycardic responses and (ii) the potential blocking effect of these antagonists on ADPβS-induced sympatho-inhibition (see below) would be related to the interaction of the antagonists with their corresponding receptors on the sympathetic cardiac nerves. Consistent with the findings of Fig. 3, clopidogrel (a P2Y12 receptor antagonist that inhibits blood clothing and that is clinically used for the treatment of thrombosis and strokes [3, 8]) is not associated with an increase in heart rate on a population basis (see below), similarly to caffeine (an adenosine A1 receptors antagonist), which also fails to affect heart rate [37]. Interestingly, the α1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin directly potentiates the tachycardic responses [38].

The lack of effect of the antagonists per se may be explained by (i) a little physiological relevance of P2Y1/P2Y12/P2Y13 receptor blockade on cardiac sympathetic nerves and/or (ii) a too slow sympatho-inhibition produced by P2Y1/P2Y12/P2Y13 receptor activation to be observed during the electrical stimulation (which lasts 10 s; see Methods section). Interestingly, since ATP is co-stored with noradrenaline [39], it is reasonable to assume that the breakdown of ATP released from sympathetic nerves would also have a prejunctional sympatho-inhibitory effect. In keeping with this notion, previous findings have suggested that as little as 3% of the ATP present at the sympathetic neuroeffector junction originates from this junction itself in rabbit aorta [14]. Therefore, we cannot rule out that the main source of ATP in our experiments is the sympathetic neuroeffector junction. Although direct cardiac sympatho-inhibitory effects resulting from prejunctional activation of α2-adrenoceptors has been shown in this model [22, 27], one might speculate that the inhibitory effect of ADP – if any – will not be seen in this time frame, as it first needs to be degraded from ATP.

Cardiac sympatho-inhibition by ADPβS: possible pharmacological correlation with the purinergic P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptor subtypes

Using the pithed rat model, it has been shown that some Gi/o-coupled receptors, including histamine H3, dopamine D2, adrenergic α2A/2C, serotonin 5-HT1B/1D and purinergic A1 receptors, produce cardiac sympatho-inhibition [20–24]. Hence, considering the pharmacological properties of the P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors [1–5], it was not surprising to us that ADPβS indeed caused a significant inhibition of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive.

In order to explain the possible role of purinergic P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors on the cardiac sympatho-inhibition produced by ADPβS, the antagonists MRS 2500, PSB 0739 and MRS 2211 were given at doses high enough (taking into consideration their affinity values [40–49]; see Table 2) to block P2Y1, P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors in the pithed rat. It is noteworthy, nevertheless, that the potential role of pharmacokinetic factors cannot be entirely ruled out. On this basis, our study shows that ADPβS-induced cardiac sympatho-inhibition was (i) unchanged by the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS 2500 (300 μg/kg; Fig. 4b), (ii) abolished by the P2Y12 receptor antagonist PSB 0739 (300 μg/kg; Figs. 4c and 5) and (iii) partially and weakly blocked (only at 0.1 Hz) by the highest dose of the P2Y13 receptor antagonist MRS 2211 (3000 μg/kg; Fig. 4e). Admittedly, we did not measure free plasma concentrations of these antagonists in our pithed rat model, but the higher affinity of PSB 0739 for the P2Y12 receptor subtype (as compared to that for the P2Y13, P2Y14 and even for the P2Y1 receptors; Table 2) and the complete blockade produced by this compound (Fig. 4c), taken together, support the main role of the P2Y12 receptor subtype. In contrast, the binding properties (Table 2) and the very weak blockade produced by the highest dose of MRS 2211 (only at 0.1 Hz; Fig. 4e) might be attributed to its moderate affinity for the P2Y12 receptor subtype (Table 2). In this respect, it must be emphasized that, if P2Y13 receptors were playing an important role under our experimental conditions, 1000 and 3000 μg/kg MRS 2211 should have produced a noticeable reversal of the ADPβS-induced cardiac sympatho-inhibition. Indeed, contrasting with Fig. 4d, in a recent study in anaesthetized rats where P2Y13 receptors are clearly involved, 1000-μg/kg MRS 2211 was high enough to revert ADPβS-induced inhibition of the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide from sensory neurons innervating the middle meningeal artery [50]. However, since the difference in binding affinities of MRS 2211 for P2Y12 and P2Y13 receptors is rather small (Table 2), and there is little room for selective blockade in pithed rats [20–23], a minor role (if any) of P2Y13 receptors cannot be categorically excluded from our findings. Consistent with this view, PSB 0739, (i) unlike clopidogrel, does not require bioactivation [44] and (ii) completely reverted the sympatho-inhibitory effect produced by ADPβS (Figs. 4c and 5). Moreover, the potential role of P2Y1 receptors in our study seems rather unlikely in view of (i) their coupling to Gq proteins [1–5], a signalling pathway unrelated to inhibition of neurotransmitter release [2, 20–23], (ii) the nearly 2 log units lower affinity of ADPβS for these receptors (at which it behaves as a partial agonist; Table 2) and (iii) the null blockade produced by i.v. administration of 300 μg/kg MRS 2500 on the ADPβS-induced cardiac sympatho-inhibition (Fig. 4b).

Perspectives and potential clinical significance

From a clinical perspective, this study provides new findings for understanding the modulation of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive and suggests that the P2Y12 receptor subtype may certainly represent a therapeutic target for the treatment of some cardiac pathologies such as myocardial ischemia [51], stroke and myocardial infarctions [8, 52]. Clearly, further in vivo studies will be required to confirm if this is the case.

On the other hand, we show that activation of P2Y12 receptors results in inhibition of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive. There are currently millions of patients using clopidogrel or similar drugs to prevent blood coagulation [16]. In these patients, no significant increases in heart rate have been reported in a cardiovascular safety study using cangrelor [53]; this result is consistent with our findings on the effect of PSB 0739 per se.

However, there are some single reports describing an increase in heart rate, among other symptoms, using a P2Y12 blocker [54]. In the light of the current research, there is no need to cause immediate worry of the widespread use of the P2Y12 antagonists, as we did not observe any effects per se (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, it is worth noting that, under pathophysiological conditions, there might be an important role of inhibitory effects of ADP on the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive. Therefore, we suggest that heart rate should be monitored in patients on P2Y12 receptor antagonists and offer a potential explanation in the cases where increased heart rate has been reported. Similar concerns for the widespread use of clopidogrel have also been raised within osteoporosis research, where treatment with clopidogrel was associated with both increased overall fracture risk and increased risk of osteoporotic fractures [55]. Accordingly, in view of the role of P2Y12 receptors and ADP in blood coagulation [3, 8, 16, 44], we have difficulties in considering the P2Y12 receptor as a potential target for lowering heart rate in patients, with the apparent risk of blood coagulation. Admittedly, the pathophysiological relevance of the P2Y12 receptor subtype needs to be further explored.

On the other hand, the purinergic involvement in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology is well documented [8]. The strongest data thus far show an important regulation of the vasculature and blood flow [12], through activation of vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells with varying expression along the vascular bed [56]. The current study adds to the understanding of the purinergic regulation in the heart. Indeed, in contrast to the positive inotropic effects of both P2X [32] and P2Y [57] receptors, their cardiac modulatory role at the postjunctional level has not received much attention. To our knowledge, the present study is the first of its kind to show that activation of P2Y12 receptors results in inhibition of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic drive in pithed rats. Hence, one might consider which receptors could counteract the P2Y12 receptor.

As a final reflection, it is important to highlight that ADPβS produces vasorelaxation in in vitro models by activation of endothelial P2Y1 receptors [58–60]. In contrast, ADPβS produced no discernible vasodepressor responses (an indicator of systemic vasodilatation) in our pithed rats. This apparent discrepancy may be due to the fact that in pithed rats, (i) the central nervous system is not functional and, accordingly, baroreflex compensatory mechanisms and central effects of compounds can be categorically excluded; (ii) the baseline values of both heart rate and diastolic blood pressure are much lower than those determined in anaesthetized or awake rats [61], which still have a neurogenic sympathetic tone; and (iii) ADPβS was given as a slow i.v. continuous infusion, not as an i.v. bolus injection. Accordingly, with our pithed rats having a very low resting diastolic blood pressure (around 30 mmHg, see results), there is little room for visualizing any further vasodepressor effects, unless this resting blood pressure was artificially increased with an i.v. continuous infusion of a vasoconstrictor agent such as methoxamine [62, 63], or by using anaesthetized or awake rats, which have a much higher resting blood pressure [61].

Conclusions

Our results, taken together, suggest that the cardiac sympatho-inhibition induced by 30 μg/kg/min of ADPβS in pithed rats is mainly mediated by activation of prejunctional P2Y12 receptors and, probably to a much lesser extent (if any), by P2Y13 receptors.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Mauricio Villasana and Engr. José Rodolfo Fernández-Calderón for their technical assistance.

Authors’ Contribution

Belinda Villanueva-Castillo designed the project, performed the experiments, analysed the data, drafted, revised and approved the final manuscript. Kristian Agmund Haanes designed the project, analysed the data, drafted, revised and approved the final manuscript. Eduardo Rivera-Mancilla and Antoinette Maassen van den Brink analysed the data, drafted, revised and approved the final manuscript. Carlos M. Villalón designed the project, supervised the experiments, analysed the data, drafted, revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding information

We are also indebted to the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT, grant No. 219707) and the SEP-Cinvestav Research Support Fund (Grant No. 50) for their financial support.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The experimental protocols of the present investigation were approved by our Institutional Ethics Committee on the use of animals on scientific experiments (CICUAL-Cinvestav; protocol number 0139-15), following the regulations established by the Mexican Official Norm (NOM-062-ZOO-1999) in accordance with the guide for the Care and Use of the Laboratory Animals in the USA [25], the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments in animals [26] and the Legislation for the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes (Directive 2010/63/EU(2010)).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Belinda Villanueva-Castillo, Email: belyndavc@hotmail.com.

Eduardo Rivera-Mancilla, Email: e.r.m_89@hotmail.com.

Kristian Agmund Haanes, Email: kristian.agmund.haanes@regionh.dk.

Antoinette MaassenVanDenBrink, Email: a.vanharen-maassenvandenbrink@erasmusmc.nl.

Carlos M. Villalón, Email: cvillalon@cinvestav.mx

References

- 1.Erb L, Weisman GA. Coupling of P2Y receptors to G proteins and other signaling pathways. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Membr Transp Signal. 2012;1:789–803. doi: 10.1002/wmts.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Kügelgen I, Nörenberg W, Koch H, Meyer A, Illes P, Starke K. P2-receptors controlling neurotransmitter release from postganglionic sympathetic neurones. Prog Brain Res. 1999;120:173–182. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63554-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: therapeutic developments. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:661. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G. Purinoceptors: are there families of P2X and P2Y purinoceptors? Pharmacol Ther. 1994;64:445–475. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnstock G. Purine and pyrimidine receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1471–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6497-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dreisig K, Kornum BR. A critical look at the function of the P2Y11 receptor. Purinergic Signal. 2016;12(3):427–437. doi: 10.1007/s11302-016-9514-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kennedy C. P2Y11 receptors: properties, distribution and functions. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1051:107–122. doi: 10.1007/5584_2017_89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnstock G. Purinergic signaling in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2017;120:207–228. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vassort G. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate: a P2-purinergic agonist in the myocardium. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:767–806. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon JL. Extracellular ATP: effects, sources and fate. Biochem J. 1986;233:309–319. doi: 10.1042/bj2330309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemens MG, Forrester T. Appearance of adenosine triphosphate in the coronary sinus effluent from isolated working rat heart in response to hypoxia. J Physiol. 1981;312:143–158. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S, Iring A, Strilic B, Albarrán Juárez J, Kaur H, Troidl K, Tonack S, Burbiel JC, Müller CE, Fleming I, Lundberg JO, Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. P2Y2 and Gq/G11 control blood pressure by mediating endothelial mechanotransduction. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3077–3086. doi: 10.1172/JCI81067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feliu C, Peyret H, Poitevin G, Cazaubon Y, Oszust F, Nguyen P, Millart H, Djerada Z. Complementary role of P2 and adenosine receptors in ATP induced-anti-apoptotic effects against hypoxic injury of HUVECs. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):E1446. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sedaa KO, Bjur RA, Shinozuka K, Westfall DP. Nerve and drug-induced release of adenine nucleosides and nucleotides from rabbit aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;252:1060–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yegutkin GG. Enzymes involved in metabolism of extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides: functional implications and measurement of activities. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49:473–497. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2014.953627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnstock G. Blood cells: an historical account of the roles of purinergic signalling. Purinergic Signal. 2015;11:411–434. doi: 10.1007/s11302-015-9462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malin SA, Molliver DC. Gi- and Gq-coupled ADP (P2Y) receptors act in opposition to modulate nociceptive signaling and inflammatory pain behavior. Mol Pain. 2010;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Queiroz G, Talaia C, Goncalves J. ATP modulates noradrenaline release by activation of inhibitory P2Y receptors and facilitatory P2X receptors in the rat vas deferens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:809–815. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quintas C, Fraga S, Goncalves J, Queiroz G. The P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors mediate autoinhibition of transmitter release in sympathetic innervated tissues. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinacho-García M, Marichal-Cancino BA, Villalón CM. Further evidence for the role of histamine H3, but no H1, H2 or H4, receptors in immepip-induced inhibition of the rat cardiaccelator sympathetic outflow. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;773:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altamirano-Espinoza AH, González-Hernández A, Manrique-Maldonado G, Marichal-Cancino BA, Ruiz-Salinas I, Villalón CM. The role of dopamine D2, but not D3 or D4, receptor subtypes, in quinpirole-induced inhibition of the cardioaccelerator sympathetic outflow in pithed rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1102–1111. doi: 10.1111/bph.12358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cobos-Puc LE, Villalón CM, Sánchez-López A, Lozano-Cuenca J, Pertz HH, Görnemann T, Centurión D. Pharmacological evidence that alpha(2A)- and alpha(2C)-adrenoceptors mediate the inhibition of cardioaccelerator sympathetic outflow in pithed rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;554:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sánchez-López A, Centurión D, Vázquez E, Arulmani U, Saxena PR, Villalón CM. Further characterization of the 5-HT1 receptors mediating cardiac sympatho-inhibition in pithed rats: pharmacological correlation with the 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D subtypes. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369:220–227. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evoniuk GE, von Borstel RW, Wurtman RJ. Adenosine affects sympathetic neurotransmission at multiple sites in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;236:350–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayne K. Revised guide for the care and use of laboratory animals available. American Physiological Society. Physiologist. 1996;39:208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Killenny C, Wainwright CL. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivera-Mancilla E, Altamirano-Espinoza AH, Manrique-Maldonado G, Villanueva-Castillo B, Villalón CM. Differential cardiac sympatho-inhibitory responses produced by the agonists B-HT 933, quinpirole and immepip in normoglycaemic and diabetic pithed rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2018;45:767–778. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinman L, Radford E. Ventilation standards for small mammals. J Appl Physiol. 1964;19:360–362. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villalón CM, Centurión D, Fernández MM, Morán A, Sánchez-López A. 5-Hydroxytryptamine inhibits the tachycardia induced by selective preganglionic sympathetic stimulation in pithed rats. Life Sci. 1999;64:1839–1847. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steel RGD, Torrie JH. Principles and procedures of statistics: a biomedical approach. 2. Tokyo: McGraw-Hill, Kogakusha Ltd; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labastida-Ramírez A, Rubio-Beltrán E, Hernández-Abreu O, Daugherty BL, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Villalón CM. Pharmacological analysis of the increases in heart rate and diastolic blood pressure produced by (S)-isometheptene and (R)-isometheptene in pithed rats. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):52–58. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0761-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mei Q, Liang BT. P2 purinergic receptor activation enhances cardiac contractility in isolated rat and mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H334–H341. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bechtel WD, Mierau J, Pelzer H. Biochemical pharmacology of pirenzepine. Similarities with tricyclic antidepressants in antimuscarinic effects only. Arzneimittelforschung. 1986;36:793–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villalón CM, Centurión D, Rabelo G, de Vries P, Saxena PR, Sánchez-López A. The 5-HT1-like receptors mediating inhibition of sympathetic vasopressor outflow in the pithed rat: operational correlation with the 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D subtypes. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:1001–1011. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villalón CM, Contreras J, Ramírez-San Juan E, Castillo C, Perusquía M, López-Muñoz FJ, Terrón JA. 5-Hydroxytryptamine inhibits pressor responses to preganglionic sympathetic nerve stimulation in pithed rats. Life Sci. 1995;57:803–812. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villalón CM, Contreras J, Ramírez-San Juan E, Castillo C, Perusquía M, Terrón JA. Characterization of prejunctional 5-HT receptors mediating inhibition of sympathetic vasopressor responses in the pithed rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:3330–3336. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bottcher M, Czernin J, Sun KT, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. Effect of caffeine on myocardial blood flow at rest and during pharmacological vasodilation. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:2016–2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schapel GJ, Betts WH. The effect of a single oral dose of prazosin on venous reflex response, blood pressure and pulse rate in normal volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;12:873–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Kugelgen I, Starke K. Noradrenaline-ATP co-transmission in the sympathetic nervous system. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90587-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang FL, Luo L, Gustafson E, Lachowicz J, Smith M, Qiao X, Liu YH, Chen G, Pramanik B, Laz TM, Palmer K, Bayne M, Monsma FJ., Jr ADP is the cognate ligand for the orphan G protein-coupled receptor SP1999. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8608–8615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang FL, Luo L, Gustafson E, Palmer K, Qiao X, Fan X, Yang S, Laz TM, Bayne M, Monsma F., Jr P2Y13: identification and characterization of a novel Gαi-coupled ADP receptor from human and mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:705–713. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldo GL, Harden TK. Agonist binding and Gq-stimulating activities of the purified human P2Y1 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:426–436. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fricks IP, Carter RL, Lazarowski ER, Harden TK. Gi-dependent cell signaling responses of the human P2Y14 receptor in model cell systems. J Pharmacol Expo Ther. 2004;330:162–168. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.150730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baqi Y, Atzler K, Kose M, Glanzel M, Muller CE. High-affinity, non-nucleotide-derived competitive antagonists of platelet P2Y12 receptors. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3784–3793. doi: 10.1021/jm9003297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffmann K, Baqi Y, Morena MS, Glänzel M, Müller CE, von Kügelgen I. Interaction of new, very potent non-nucleotide antagonists with Arg256 of the human platelet P2Y12 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:648–655. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim YC, Lee JS, Sak K, Marteau F, Mamedova L, Boeynaems JM, Jacobson KA. Synthesis of pyridoxal phosphate derivatives with antagonist activity at the P2Y13 receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cattaneo M, Lecchi A, Ohno M, Joshi BV, Besada P, Tchilibon S, Lombardi R, Bischofberger N, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. Antiaggregatory activity in human platelets of potent antagonist of the P2Y 1 receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1995–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marteau F, Le Poul E, Communi D, Communi D, Labouret C, Savi P, Boeynaems JM, Gonzalez NS. Pharmacological characterization of the human P2Y13 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:104–112. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim HS, Ohno M, Xu B, Kim HO, Choi Y, Ji XD, Maddileti S, Marquez VE, Harden TK, Jacobson KA. 2-substitution of adenine nucleotide analogues containing a bycyclo[3.1.0]hexane ring system locked in a northern conformation: enhanced potency as P2Y1 receptor antagonist. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4974–498777. doi: 10.1021/jm030127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haanes KA, Labastida-Ramírez A, Blixt FW, Rubio-Beltrán E, Dirven CM, Danser AH, Edvinsson L, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Exploration of purinergic receptors as potential anti-migraine targets using established pre-clinical migraine models. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:1421–1434. doi: 10.1177/0333102419851810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Djerada Z, Feliu C, Richard V, Millart H. Current knowledge on the role of P2Y receptors in cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion. Pharmacol Res. 2017;118:5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Erlinge D, Burnstock G. P2 receptors in cardiovascular regulation and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9078-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green C, Whellan DJ, Lambe L, Bellibas SE, Wijngaard P, Prats J, Krucoff MW. Electrocardiographic safety of cangrelor, a new intravenous antiplatelet agent: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and moxifloxacin-controlled thorough QT study. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2013;62:466–478. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182a2630d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doogue MP, Begg EJ, Bridgman P. Clopidogrel hypersensitivity syndrome with rash, fever, and neutropenia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1368–1370. doi: 10.4065/80.10.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jorgensen NR, Grove EL, Schwarz P, Vestergaard P. Clopidogrel and the risk of osteoporotic fractures: a nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med. 2012;272:385–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haanes KA, Spray S, Syberg S, Jørgensen NR, Robaye B, Boeynaems JM, Edvinsson L. New insights on pyrimidine signalling within the arterial vasculature - different roles for P2Y2 and P2Y6 receptors in large and small coronary arteries of the mouse. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;93:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wihlborg AK, Balogh J, Wang L, Borna C, Dou Y, Joshi BV, Lazarowski E, Jacobson KA, Arner A, Erlinge D. Positive inotropic effects by uridine triphosphate (UTP) and uridine diphosphate (UDP) via P2Y2 and P2Y6 receptors on cardiomyocytes and release of UTP in man during myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2006;98:970–976. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000217402.73402.cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bender SB, Berwick ZC, Laughlin MH, Tune JD (1985) Functional contribution of P2Y1 receptors to the control of coronary blood flow. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2011;111(6):1744-50. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00946.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Actions mediated by P2-purinoceptor subtypes in the isolated perfused mesenteric bed of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1988;95(2):637–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50(3):413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Centurión D, Glusa E, Sánchez-López A, Valdivia LF, Saxena PR, Villalón CM. 5-HT7, but not 5-HT2B, receptors mediate hypotension in vagosympathectomized rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;502(3):239–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taguchi T, Kawasaki H, Imamura T, Takasaki K. Endogenous calcitonin gene-related peptide mediates nonadrenergic noncholinergic depressor response to spinal cord stimulation in the pithed rat. Circ Res. 1992;71(2):357–364. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.71.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Villalón CM, Albarrán-Juárez JA, Lozano-Cuenca J, Pertz HH, Görnemann T, Centurión D. Pharmacological profile of the clonidine-induced inhibition of vasodepressor sensory outflow in pithed rats: correlation with alpha(2A/2C)-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(1):51–59. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]