Abstract

A novel simultaneous detection system for human viruses was developed using a real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system to identify causes of infection in clinical samples from patients with uncertain diagnoses. This system, designated as the “multivirus real‐time PCR,” has the potential to detect 163 human viruses (47 DNA viruses and 116 RNA viruses) in a 96‐well plate simultaneously. The specificity and sensitivity of each probe–primer set were confirmed with cells or tissues infected with specific viruses. The multivirus real‐time PCR system showed profiles of virus infection in 20 autopsies of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients, and detected frequently TT virus, cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 6, and Epstein–Barr virus in various organs; however, RNA viruses were detected rarely except for human immunodeficiency virus‐1. Pathology samples from 40 patients with uncertain diagnoses were examined, including cases of encephalitis, hepatitis, and myocarditis. Herpes simplex virus 1, human herpesvirus 6, and parechovirus 3 were identified as causes of diseases in four cases of encephalitis, while no viruses were identified in other cases as causing disease. This multivirus real‐time PCR system can be useful for detecting virus in specimens from patients with uncertain diagnoses. J. Med. Virol. 83:322–330, 2011. © 2010 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: real‐time PCR, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), virus, autopsy

INTRODUCTION

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a powerful tool to detect viruses compared with some traditional methods such as the direct fluorescent‐antibody assay or virus isolation in cell culture. Real‐time PCR is a sensitive system to detect viral genomes, used commonly worldwide [Storch, 2000]. Moreover, multiplex PCR fluorescence techniques are able to identify several genes in one tube simultaneously. Some reports have described simultaneous detection systems for up to 20 viruses using real‐time PCR or conventional PCR [Vet et al., 1999; Bellau‐Pujol et al., 2005; Li et al., 2007; Mahony et al., 2007; Molenkamp et al., 2007; Nolte et al., 2007; van de Pol et al., 2007; Wada et al., 2009]. However, the number of viruses detectable in one tube is limited by fluorescence wavelength. On the other hand, microarray analysis can detect a large number of viruses simultaneously. The weak point of the microarray assay is its low sensitivity and specificity [Wang et al., 2002].

It has been demonstrated that many viruses are associated with human diseases, and such human pathogenic viruses include both DNA and RNA viruses. An ideal virus screening system may be a system capable of detecting all the human pathogenic viruses simultaneously. In the present study, a real‐time PCR system capable of detecting more than one hundred human viruses in a 96‐well reaction plate simultaneously was established, designated as the “multivirus real‐time PCR” system. In this system, two viruses are detected in one well using a duplex TaqMan real‐time reverse transcriptase (RT)‐PCR system; since more than 82 different duplex real‐time PCRs are performed in a 96‐well plate except wells for standard curve and internal controls, theoretically 163 human viruses can be detected in a 96‐well plate simultaneously. Using this system, the distribution and quantification of viruses were investigated in organ specimens from autopsies of 20 acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients. In addition, clinical samples from patients with uncertain diagnoses were examined to identify the causes of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Probe–Primer Sets

A total of 163 human viruses were selected as targets (Table I). The choice of the viruses was based on their associations with human diseases, prevalence among humans, and possibility of the usages as vectors to human cells. Probe–primer sets for each virus were designed using Primer Express 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) (Supplementary Table I). Probe–primer sets published elsewhere were employed for some of the viruses. Probes and primers were synthesized by Sigma Genosys (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Probes were labeled with 6‐carboxyfluorescein (FAM)—6‐carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) or hexacholoro‐6‐carboxyfluorescein (HEX)—non‐fluorescent Black Hole Quencher (BHQ)‐1. Each probe–primer set was confirmed to react with at least 10 copies of a positive control plasmid containing each virus fragment, using conventional TaqMan real‐time PCR (Applied Biosystems).

Table I.

List of Target Viruses

| DNA virus |

| Polyomavirus: JC virus, BK virus, Simian virus 40 |

| Papillomavirus: Human papillomavirus 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73 |

| Parvovirus: Adeno‐associated virus 1, 2, 3, 5; Parvovirus B19; human bocavirus; adenovirus A, B, C, D, E, F |

| Herpes virus: Human herpesvirus 1–8, B virus |

| Poxvirus: Variola virus, Monkey pox virus, Molluscum contagiosum virus |

| Anellovirus: Torque teno virus |

| Hepadnavirus: Hepatitis B virus |

| Other: Mimivirus |

| RNA virus |

| Filovirus: Ebola virus, Marburg virus |

| Bunyavirus: Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome virus (Hantaan, Dovrava, Puumala, and Seoul), Rift valley fever virus, Sin Nombre virus |

| Arenavirus: Lassa virus, Junin, Guanarito, Machupo, Sabia |

| Togavirus: Equine encephalitis virus (Venezuelan, Eastern, and Western), Sindbis virus, Mayaro virus, Getah virus, Chikungunya virus, Rubella virus |

| Enterovirus: Enterovirus 68, 71; Poliovirus 1,2,3; Coxsackievirus A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A8, A9, A10, A16, A21, A24, B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, B6; Echovirus 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 25, 30; Parechovirus 1, 3; Rhinovirus A, B; rotavirus; reovirus 1–4; Melaka virus; Colorado tick borne fever virus |

| Flavivirus: Dengue virus 1, 2; Japanese encephalitis virus; Murray Valley encephalitis virus; St. Louis encephalitis virus; West Nile virus; Tick‐borne encephalitis virus; Yellow fever virus |

| Orthomyxovirus: Influenza virus A, B, C; H5N1 |

| Paramyxovirus: Parainfluenza virus 1–3; Hendra virus; Mumps virus; Measles virus; Sendai virus; RS virus A, B; metapneumovirus; Nipah virus |

| Rabdovirus: Rabies virus; Lyssavirus 5, 6; Chandipura virus; Duvenhage virus |

| Coronavirus: Coronavirus OC43, 229E, NL63, SARS virus |

| Calicivirus: Sapovirus, Norwalk‐like virus 1, 2 |

| Hepatitis virus: Hepatitis A virus, Hepatitis C virus, Hepatitis D virus, Hepatitis E virus, GB virus |

| Retrovirus: human immunodeficiency virus 1; human T cell leukemia virus 1, 2; human endogenous retrovirus K, H, W |

| Other: Astrovirus, Borna disease virus |

Establishment of Multivirus Real‐Time PCR

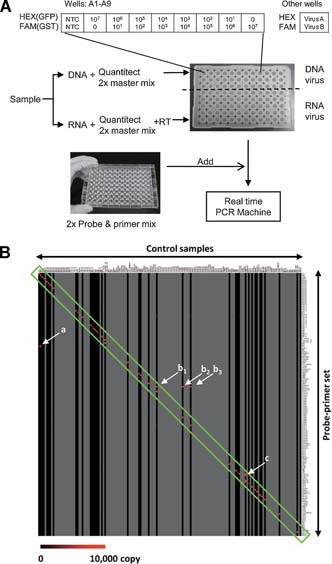

A duplex TaqMan real‐time RT‐PCR system was designed to detect many viruses in a 96‐well plate. Design of this system, designated as the “multivirus real‐time PCR,” is shown in Figure 1A. Quantitect Multiplex Probe RT‐PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), MicroAmp Optical 96‐Well Reaction Plates (Applied Biosystems), and MicroAmp Optical Adhesive Film (Applied Biosystems) were used as 2× master mix, 96‐well plates, and adhesive film, respectively. Each well contains two probe–primer sets with 6‐FAM‐ and HEX‐labeled probes, allowing two viruses were to be detected in each well, and the 163 viruses listed in Table I to be detected in a 96‐well plate simultaneously. A standard curve was established for nine wells of each plate (A1–A9), which contained FAM‐ or HEX‐labeled probes and primers for green fluorescent protein and glutathione S‐transferase genes with control plasmids at 101 to 107 copies. Thus, an approximate copy number of each virus could be calculated based on the standard curve. To use the system routinely, 2× probe–primer mix was stored in a 96‐well plate at −20°C. For detection of viruses, DNA and RNA samples (50 ng per well) were added to 2× master mix with (for RNA) and without (for DNA) RT. When sufficient amounts of DNA or RNA were not obtained from clinical samples, <50 ng of DNA or RNA per well were applied in this system. Ten microliters of 2× probe–primer mix and 10 µl of 2× master mix with sample DNA (36 wells) or RNA (60 wells) were then mixed in a 96‐well reaction plate. Real‐time RT‐PCR was performed in an ABI PRISM 7900HT (Applied Biosystems) or an Mx3005P (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The RT‐PCR conditions were 50°C for 30 min and 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 1 min. Quantitative results of viruses were obtained by generating standard curves for two plasmids in the A1–A9 wells. Real‐time PCR using a condition for RT‐PCR (50°C for 30 min and 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min) had similar sensitivity to real‐time PCR using usual DNA conditions (95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min) in the detection for some DNA viruses (Supplementary Fig. 1A). In addition, the duplex real‐time PCR using Quantitect Multiplex Probe RT‐PCR kit (Qiagen) had similar sensitivity to single real‐time PCR procedures using Quantitect Probe RT‐PCR kit (Qiagen) in several probe–primer sets (Supplementary Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Establishment and validation of multivirus real‐time PCR. A: Procedure of the multivirus real‐time PCR system. DNA sample was mixed with Quantitect 2× master mix, and RNA sample was mixed with Quantitect 2× master mix and reverse transcriptase (RT) mix. These mixtures were poured into each well in a 96‐well plate at 10 µl per well. Ten microliters of 2× probe and primer mix were then added to each well in a premixed 96‐well plate. Finally, the virus genes were amplified and detected in a real‐time PCR machine for 2 hr. B: Validation of the multivirus real‐time PCR. A gene expression image by TreeView software based on the results of the multivirus real‐time PCR for control samples is shown. A horizontal line shows each probe–primer set and a vertical line is one sample of positive control. Gray vertical lines indicate no sample. A scale bar indicates copy number of color. A green box indicates specific reactions of target positive controls in specific probe–primer sets. Arrows of (a–c) also show specific signals. The arrow (a) shows positive signal for TTV in a brain sample with both JCV and TTV infection. The arrows (b1–3) show that a probe–primer set for pan‐enterovirus reacted with poliovirus (b1), Coxsackievirus B3 (b2), and Echovirus 6 (b3) positive samples. The arrow (c) shows that a probe–primer set for influenza virus A reacted with H5N1 influenza virus. Details of positive controls were listed in Supplementary Table II.

Gene Expression Image

A gene expression image was produced with TreeView and Cluster software by Michael Eisen, University of California at Berkeley (http://rana.lbl.gov/EisenSoftware.htm) [Eisen et al., 1998].

Determination of the Positivity and Copy Numbers of Viruses

The positivity and virus titer of all positive samples were confirmed with individual standard real‐time (RT‐) PCR systems using the same probe–primer sets. Virus DNA copy numbers per cell were calculated by dividing virus DNA copy numbers by half of beta‐actin copy numbers, since each cell has two copies of DNA in two alleles [Asahi‐Ozaki et al., 2006].

Patients and Samples

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan (Approval No. 156). Tissues were taken at autopsy from various organs of 20 patients with AIDS. All tissues were frozen immediately, and stored at −80°C. The clinical information of the patients is summarized in Table II. A total of 19 patients were male. The mean age of the patients was 41.8 years (range: 19–67 years), and the mean of CD4 counts was 17 cells/µl (range: 0–241). Risk factors for HIV infection in the patients were men who had sex with men (10), heterosexuality (5), and hemophilia (5). At least seven patients had lymphoma, and two had Kaposi's sarcoma. No patients received highly active anti‐retroviral therapy (HAART). In addition, 40 clinical samples from patients with uncertain diagnoses were investigated (Table III). These clinical samples were sent to our department for virus diagnosis. Informed consents were obtained by the clinical doctors. Positive control DNA or RNA samples extracted from virus‐infected cells or tissues were kindly provided by many researchers in National Institute of Infectious Diseases (Supplementary Table II).

Table II.

Clinical Information and Detected Viruses in AIDS Autopsies

| Case no. | Age | Sex | Risk factor | Complications | CD4a | Detected viruses by multivirus real‐time PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 49 | M | MSM | PCP, aspergillus | NT | TTV, HBV, HERV‐H |

| 2 | 37 | M | MSM | CMV, toxoplasma, PCP | NT | HSV‐1, CMV, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 3 | 29 | M | Drug | PCP | 1 | JCV, Adv‐B, HSV‐1, EBV, CMV, HHV‐6, HHV‐7, TTV, HBV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 4 | 37 | M | Blood product | MAC, CMV | 1 | EBV, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 5 | 43 | M | Heterosexual | ML, CMV, cryptococcus | 5 | B19, Adv‐A, EBV, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 6 | 54 | M | MSM | CMV | NT | EBV, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, HBV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 7 | 33 | M | MSM | CMV | 4 | B19, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 8 | 47 | M | MSM | HIV‐encephalitis, KS, ML | 1 | BKV, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, HIV‐1, HCV |

| 9 | 35 | M | Blood product | CMV | 1 | B19, CMV, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 10 | 27 | F | Heterosexual | ML, MAC, CMV | 3 | BKV, EBV, CMV, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 11 | 50 | M | MSM | HIV‐encephalitis, ML, cryptococcus, CMV | 0 | B19, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 12 | 19 | M | Blood product | HIV‐encephalitis | 2 | BKV, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 13 | 26 | M | Blood product | PML | 3 | JCV, BKV, B19, Adv‐B, EBV, HHV‐6, HHV‐7, TTV, Echo6, HCV, HERV‐H |

| 14 | 67 | M | MSM | ML | 241 | JCV, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 15 | 62 | M | MSM | CMV, PCP | 4 | AAV‐2, B19, EBV, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 16 | 28 | M | Blood product | CMV, MAC | 3 | JCV, BKV, B19, CMV, HHV‐7, TTV, HBV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 17 | 46 | M | Heterosexual | ML, aspergillus, CMV | 5 | BKV, AAV‐2, B19, Adv‐D, EBV, CMV, HHV‐6, TTV, RSV‐B, HIV‐1 |

| 18 | 47 | M | MSM | PEL, CMV | 7 | JCV, B19, EBV, CMV, HHV‐6, HHV‐8, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐K, HERV‐H |

| 19 | 60 | M | MSM | ML, CMV, KS | 1 | B19, CMV, TTV, HIV‐1, HERV‐H |

| 20 | 40 | M | Heterosexual | CMV | NT | BKV, AAV‐2, CMV, HHV‐6, HHV‐7, TTV, HBV, HERV‐H |

AAV, adeno‐associated virus; Adv, adenovirus; B19, parvovirus B19; BKV, BK virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HERV, human endogenous retrovirus; HHV, human herpesvirus; HIV‐1, human immunodeficiency virus 1; HSV, herpes simplex virus; JCV, JC virus; KS, Kaposi's sarcoma; MAC, mycobacterium avium‐intracellulare complex; ML, malignant lymphoma; MSM, Men who have sex with men; NT, not tested; PCP, Pneumocystis pneumonia; PML, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; TTV, Torque teno virus.

CD4 counts per µl.

Table III.

Identification of Pathogenic Virus in Clinical Samples From Patients With Uncertain Diagnoses

| Patients | n | Samples | Identified pathogens (cases) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis | 9 | Liver biopsy | Parvovirus B19 (2), HHV‐6 (3), TTV (2) |

| Encephalitis | 11 | Brain biopsy, serum, cerebral fluids | HSV‐1 (2), HHV‐6 (1), parechovirus 3 (1) |

| Myocarditis | 6 | Heart autopsy | Parvovirus B19 (1), TTV (2) |

| Sudden death | 4 | Blood, serum | TTV (1) |

| Other | 10 | Tissue, blood, serum | Parvovirus B19 (1), EBV (1), CMV (1), HHV‐7 (1), TTV (2) |

| Total | 40 | — | — |

Etiological viruses in the cases are underlined.

DNA and RNA Extraction

Nucleic acid extraction methods differed according to the type of samples. Each frozen tissue sample was divided in two, one part for DNA extraction and another for RNA extraction. For DNA extraction, the samples were homogenized with Multi‐Beads Shocker (Yasui Kikai, Tokyo, Japan) in TEN buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, and 100 mM NaCl) with 100 ng/ml proteinase K and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. DNA was extracted from the homogenized tissues using the phenol–chloroform method. Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues using Isogen (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan). The samples were homogenized in the Isogen with Multi‐Beads Shocker, and the extraction was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. For small samples including tissue biopsy, blood, serum and cerebral fluid, both DNA and RNA were extracted simultaneously with All Prep Kit (Qiagen). All RNA samples were treated with DNase (Turbo DNA‐Free, Ambion, Austin, TX) for 20 min according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Validation of Multivirus Real‐Time PCR

To validate the sensitivity and specificity of each probe and primer set used in the system, DNA or RNA samples extracted from virus‐infected cells, supernatants, body fluids, or tissues were examined in this multivirus real‐time PCR system (Supplementary Table II). Each probe and primer set amplified a gene fragment of target virus specifically (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table II). When using supernatants of virus‐infected cells, the reactions were specific. Some samples of supernatants were positive for two or three viruses, because the target virus belonged to several categories. For example, the RNA sample extracted from supernatants of H5N1 influenza virus‐infected cells was positive in the wells with probe and primer sets for both H5N1 influenza virus and influenza‐A virus. Some clinical samples, such as pathological samples and body fluids, were positive for other viruses as well as target viruses because of the presence of such viruses in the samples (Supplementary Table II and Fig. 1B, arrow (a)). Although not all positive control samples could be collected, the results confirmed the adequate specificity of each probe–primer set for its target virus for virus screening. The multivirus real‐time PCR system also detects human internal control genes such as glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, DNA, and mRNA), beta‐actin (DNA), and beta‐2‐microgloblin (mRNA) (Supplementary Tables I and II). It is known that certain specimen such as serum may have inhibitory effects on PCR [Vandenvelde et al., 1993; Willems et al., 1993]. Copy numbers of internal controls would be informative to know cell numbers and inhibitory effect by the sample.

Detection of Viruses in AIDS Autopsies

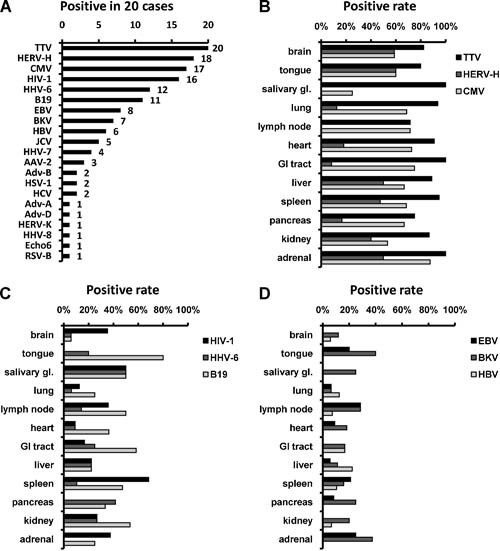

Using the multivirus real‐time PCR, the presence of viruses was investigated in 20 AIDS autopsies. The multivirus real‐time PCR detected 15 DNA viruses: JC virus (JCV), BK virus (BKV), adeno‐associated virus (AAV)‐2, parvovirus B19, three subgroups of adenovirus (A, B, and D), herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV‐1), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus (HHV)‐6, ‐7, ‐8, TT virus (TTV), and hepatitis B virus (HBV). It also detected six RNA viruses: echovirus 6, respiratory syncytial (RS) virus type B, hepatitis C virus (HCV), HIV‐1, and human endogenous retrovirus (HERV)‐H and ‐K, in 20 cases of AIDS autopsies (Fig. 2). A few other viruses were detected at low copies in some samples, but additional individual standard real‐time (RT‐) PCR systems using the same probe–primer sets showed negative results, indicating that they were false positive. Although HIV‐1 infections were confirmed clinically in all the patients, HIV‐1 was not detected in four of the autopsy cases, even using both DNA and RNA samples. TTV, HERV‐H, CMV, HIV, HHV‐6, parvovirus B19, EBV, BKV, and HBV were detected in many organs, suggesting broad distribution (Fig. 2B–D). On the other hand, the positive rate of each virus differed among organs. CMV was detected most frequently in the adrenal gland, but HIV‐1 was most common in the spleen, HHV‐6 in the salivary gland, and HBV in the liver.

Figure 2.

Viruses detected in autopsied organs of AIDS patients. A: Positive number of each virus in the 20 cases of AIDS autopsy. B–D: Positive rates of CMV, HIV‐1, and HHV‐6 in organs. GI, gastrointestinal.

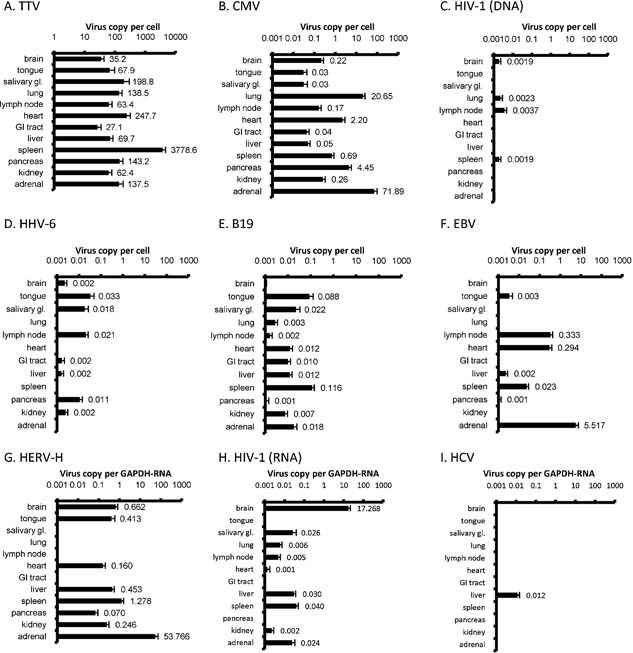

The multivirus real‐time PCR also revealed copy numbers of each virus in AIDS autopsy (Fig. 3). High numbers of TTV copies were detected frequently in various organs without any symptoms, suggesting a ubiquitous distribution in the samples and no association with any specific diseases (Fig. 3A). High numbers of CMV copies were detected in adrenal gland, lung, and pancreas (Fig. 3B). To confirm the results of the real‐time PCR, CMV positivity was investigated using inclusion bodies in the pathological samples. Inclusion bodies of CMV were detected frequently in the adrenal gland, pancreas, and lung of AIDS autopsy cases (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results correlated with those of the real‐time PCR. HHV‐6 and parvovirus B19 showed low copy numbers in all the organs tested (Fig. 3D,E). High numbers of EBV copies were detected in the heart and adrenal gland, as well as lymph node and spleen (Fig. 3F). However, the heart and adrenal samples included lesions of EBV‐associated lymphomas. Thus, EBV was detected in the lymphomas in those samples. The lymphomas in adrenal glands also included high numbers of HERV‐H copies, affecting the results of HERV‐H copy numbers in adrenal glands (Fig. 3G). High numbers of HIV‐1‐RNA copies, but not HIV‐1‐DNA, were also found in the brain of one case with HIV‐1 encephalopathy (Fig. 3C,H). HCV was detected only in the liver of two patients (Fig. 3I).

Figure 3.

Mean values of virus copy numbers in organs. Mean of copy numbers per cells are shown in DNA samples (A–F). Mean ratios of virus copy number per hGAPDH‐RNA copy number are shown in RNA samples (G–I). Error bars show standard errors. One brain sample contained HIV‐associated encephalopathy (C,H), and one of the heart and adrenal sample contained EBV‐associated lymphoma (F).

Identification of Virus in Clinical Samples From Patients With Uncertain Diagnoses

Using the multivirus real‐time PCR, clinical samples from 40 patients with uncertain diagnoses were examined to identify their causes of infection (Table III). The multivirus real‐time PCR system identified HSV‐1, HHV‐6, or parechovirus 3 as a possible cause of infection in 4 out of 11 patients with encephalitis. HSV‐1 was identified in brain biopsy tissues from two patients with encephalitis. A high copy number of HHV‐6 was detected in the serum of a patient (1.5 × 107 copies/ml in the serum). In another patient, parechovirus 3 were detected in cerebral fluids. The presence of these viruses in the samples was confirmed by individual real‐time PCR specific for each virus, and conventional (RT‐) PCR. Clinical manifestations of these four patients were compatible with the virus infections. In addition, 29 samples from patients with other diseases such as myocarditis, hepatitis, and sudden death were examined. Parvovirus B19, EBV, CMV, HHV‐6, HHV‐7, and TTV were detected in the samples; however, the titers of these viruses were low. In addition, immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization could not detect the viruses in the samples. It was therefore concluded that these viruses were not the causes of diseases in the cases.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, a new real‐time PCR system was developed, designated as the “multivirus real‐time PCR,” that had the potential to detect 163 viruses simultaneously. This multivirus real‐time PCR can detect 47 DNA viruses and 116 RNA viruses on a 96‐well plate theoretically. This system revealed the anatomical distributions of human pathogenic viruses in AIDS autopsy cases. In addition, viruses were identified in four cases of encephalitis as the cause of infection. This multivirus real‐time PCR system could be a useful technique for detection of virus in specimens from patients with uncertain diagnoses.

Real‐time PCR is a sensitive detection system for the diagnosis of virus infection. TaqMan PCR has a high specificity compared with other systems because of its specific fluorescence probes. In addition, recent multiplex fluorescence technology is able to detect several genes in each tube without non‐specific cross‐reactions. Since one‐step real‐time RT‐PCR employs specific primers as RT primers, with targets shorter than 100 bp, this system can detect short fragments of RNA viruses specifically with high sensitivity. The sensitivity and specificity of this system are equivalent to those of standard real‐time PCR systems (Supplementary Fig. 1), and its sensitivity would be much higher than in microarray systems. In addition, the multivirus real‐time PCR system requires only 5 µg each of DNA and RNA for detecting 163 viruses.

One disadvantage of this system is cost. To establish this system, 176 probe–primer sets should be prepared. Moreover, about 1 ml of Quantitect 2× master mix was used in single reaction of 96‐well plate, which costs about 25,000 yen (approximately 263 U.S. dollars; containing probe–primer sets: ¥36 × 176 sets = ¥6,336, Quantitect 2× master mix: ¥16,000, filtered tips, 96‐well reaction plate and seal: ¥2,664) per sample in a 96‐well plate reaction to test. However, once the system is established, the procedure is very easy and takes 3 hr to obtain the results. Thus, the newly developed multivirus real‐time PCR could be a useful tool for detecting pathogens in specimens from patients with uncertain diagnoses.

There is little current information about quantification of pathogenic viruses in immunocompromised hosts. Chen and Hudnall [2006] described anatomical mapping of herpes viruses in eight autopsy cases, including two AIDS cases. The multivirus real‐time PCR showed that 21 of the 163 probe–primer sets for virus produced positive reactions in AIDS autopsy samples. Many RNA viruses were negative in all cases. Although the low detection rate of RNA viruses might be associated with the quality of extracted RNA, these results suggest that the AIDS patients in the present study were infected with limited types of viruses. TTV and HHV‐6 were detected frequently in AIDS autopsy samples and some clinical samples. TTV was identified from a hepatitis patient as a hepatitis‐associated virus [Nishizawa et al., 1997]. However, TTV, a ubiquitous virus, was shown to be present in various tissues [Okamoto, 2009]. Although TTV titers were relatively high compared with those of other viruses, broad TTV distribution suggests that it is not associated with specific diseases in immunocompromised hosts. HHV‐6 is another ubiquitous virus with which almost 100% of adults are infected. Primary infection of HHV‐6 causes exanthema subitum in children [Yamanishi et al., 1988]. Reactivation of HHV‐6 may cause hepatitis, pneumonia, and encephalitis in immunocompromised hosts, such as transplant patients [Ljungman, 2002]. The average number of HHV‐6 copies in the HHV‐6‐positive samples in AIDS autopsy was 0.008 copies per cell, suggesting low numbers of HHV‐6 copies in the organs. On the other hand, HHV‐6 was identified as a possible cause of infection in a clinical case of encephalitis because of extremely high numbers of copies in the serum and clinical manifestations [Ogata et al., 2010]. Thus, a virus's copy number is important information to estimate its etiology. CMV was frequently detected in AIDS autopsy samples by the multivirus real‐time PCR system. High CMV copy numbers in the adrenal gland, pancreas and lung were associated with the occurrence of CMV‐associated adrenitis, pancreatitis, and pneumonia. CMV was detected frequently in the adrenal gland [Pulakhandam and Dincsoy, 1990]. The results of CMV detection in multivirus real‐time PCR were correlated highly with the frequency of CMV inclusion bodies on the slides, suggesting that the occurrence of CMV‐associated diseases is associated with virus titers of CMV in organs.

The multivirus real‐time PCR failed to detect HIV‐1 DNA or RNA in 4 cases out of 20 AIDS autopsies. There are several possible explanations for these results. Although none of the patients received HAART, HIV‐1 titers always change in AIDS patients [Ho et al., 1989]; the autopsy samples might have had insufficient HIV‐1 titers for detection by real‐time PCR. Also, the probe and primers used in this system might not detect the HIV‐1 because of mutations in the target regions. Mutations in HIV‐1 occur so frequently that it is difficult to detect HIV‐1 using one or two probe–primer sets [Desire et al., 2001; Yun et al., 2002].

Consequently, a multivirus real‐time PCR system with the potential to detect 163 viruses simultaneously has been established in the present study. Although the system has some disadvantages with regard to cost and procedure, it will be a powerful tool for virus screening of clinical samples in laboratories. Since it is relatively easy to change probe–primer sets in the 96‐well plate, it is possible for this system to change detectable viruses, implying that a new system detecting new viruses can be established quickly. Future refinement of its operation, such as higher throughput and microfluid techniques, may resolve the disadvantages of this system.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Table 1. Sequences of probes and primers

Supplementary Table 2. Validation of the multivirus real‐time PCR.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Kouta Sakamoto and Ms. Yuko Sato for technical assistant and Dr. Tadahito Kanda, Dr. Sei‐ichiro Mori, Dr. Takato Odagiri, Dr. Atsushi Kato, Dr. Katsuhiro Komase, Dr. Fumihiro Taguchi, Dr. Kei Numazaki, Dr. Shigeru Morikawa, Dr. Tomohiko Takasaki, Dr. Naoki Inoue, Dr. Tetsuro Suzuki, Dr. Naokazu Takeda, Dr. Tetsuo Yoneyama, Dr. Hiroyuki Shimizu, Dr. Haruko Shirato, Dr. Toshihiko Matsukura, Dr. Asato Kojima, Dr. Hidehiro Takahashi, Dr. Kenzo Tokunaga, Dr. Michiko Tanaka, Dr. Kiyoko Ogawa‐Goto, and Dr. Yasuko Asahi‐Ozaki of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases for providing positive controls for RNA or DNA extracted from virus‐infected cells.

REFERENCES

- Asahi‐Ozaki Y, Sato Y, Kanno T, Sata T, Katano H. 2006. Quantitative analysis of Kaposi sarcoma‐associated herpesvirus (KSHV) in KSHV‐associated diseases. J Infect Dis 193: 773–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellau‐Pujol S, Vabret A, Legrand L, Dina J, Gouarin S, Petitjean‐Lecherbonnier J, Pozzetto B, Ginevra C, Freymuth F. 2005. Development of three multiplex RT‐PCR assays for the detection of 12 respiratory RNA viruses. J Virol Methods 126: 53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Hudnall SD. 2006. Anatomical mapping of human herpesvirus reservoirs of infection. Mod Pathol 19: 726–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desire N, Dehee A, Schneider V, Jacomet C, Goujon C, Girard PM, Rozenbaum W, Nicolas JC. 2001. Quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral load by a TaqMan real‐time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 39: 1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. 1998. Cluster analysis and display of genome‐wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 14863–14868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DD, Moudgil T, Alam M. 1989. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the blood of infected persons. N Engl J Med 321: 1621–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, McCormac MA, Estes RW, Sefers SE, Dare RK, Chappell JD, Erdman DD, Wright PF, Tang YW. 2007. Simultaneous detection and high‐throughput identification of a panel of RNA viruses causing respiratory tract infections. J Clin Microbiol 45: 2105–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljungman P. 2002. Beta‐herpesvirus challenges in the transplant recipient. J Infect Dis 186: S99–S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony J, Chong S, Merante F, Yaghoubian S, Sinha T, Lisle C, Janeczko R. 2007. Development of a respiratory virus panel test for detection of twenty human respiratory viruses by use of multiplex PCR and a fluid microbead‐based assay. J Clin Microbiol 45: 2965–2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenkamp R, van der Ham A, Schinkel J, Beld M. 2007. Simultaneous detection of five different DNA targets by real‐time Taqman PCR using the Roche LightCycler480: Application in viral molecular diagnostics. J Virol Methods 141: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa T, Okamoto H, Konishi K, Yoshizawa H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. 1997. A novel DNA virus (TTV) associated with elevated transaminase levels in posttransfusion hepatitis of unknown etiology. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 241: 92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolte FS, Marshall DJ, Rasberry C, Schievelbein S, Banks GG, Storch GA, Arens MQ, Buller RS, Prudent JR. 2007. MultiCode‐PLx system for multiplexed detection of seventeen respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbiol 45: 2779–2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata M, Satou T, Kawano R, Takakura S, Goto K, Ikewaki J, Kohno K, Ikebe T, Ando T, Miyazaki Y, Ohtsuka E, Saburi Y, Saikawa T, Kadota J. 2010. Correlations of HHV‐6 viral load and plasma IL‐6 concentration with HHV‐6 encephalitis in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 45: 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto H. 2009. History of discoveries and pathogenicity of TT viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 331: 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulakhandam U, Dincsoy HP. 1990. Cytomegaloviral adrenalitis and adrenal insufficiency in AIDS. Am J Clin Pathol 93: 651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch GA. 2000. Diagnostic virology. Clin Infect Dis 31: 739–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Pol AC, van Loon AM, Wolfs TF, Jansen NJ, Nijhuis M, Breteler EK, Schuurman R, Rossen JW. 2007. Increased detection of respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses, parainfluenza viruses, and adenoviruses with real‐time PCR in samples from patients with respiratory symptoms. J Clin Microbiol 45: 2260–2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenvelde C, Scheen R, Defoor M, Duys M, Dumon J, Van Beers D. 1993. Suppression of the inhibitory effect of denatured albumin on the polymerase chain reaction by sodium octanoate: Application to routine clinical detection of hepatitis B virus at its infectivity threshold in serum. J Virol Methods 42: 251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vet JA, Majithia AR, Marras SA, Tyagi S, Dube S, Poiesz BJ, Kramer FR. 1999. Multiplex detection of four pathogenic retroviruses using molecular beacons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6394–6399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K, Mizoguchi S, Ito Y, Kawada J, Yamauchi Y, Morishima T, Nishiyama Y, Kimura H. 2009. Multiplex real‐time PCR for the simultaneous detection of herpes simplex virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 7. Microbiol Immunol 53: 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Coscoy L, Zylberberg M, Avila PC, Boushey HA, Ganem D, DeRisi JL. 2002. Microarray‐based detection and genotyping of viral pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 15687–15692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems M, Moshage H, Nevens F, Fevery J, Yap SH. 1993. Plasma collected from heparinized blood is not suitable for HCV‐RNA detection by conventional RT‐PCR assay. J Virol Methods 42: 127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanishi K, Okuno T, Shiraki K, Takahashi M, Kondo T, Asano Y, Kurata T. 1988. Identification of human herpesvirus‐6 as a causal agent for exanthem subitum. Lancet 1: 1065–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun Z, Fredriksson E, Sonnerborg A. 2002. Quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA by the TaqMan real‐time PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 40: 3883–3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supplementary Table 1. Sequences of probes and primers

Supplementary Table 2. Validation of the multivirus real‐time PCR.